Enhancing Phenanthrene Degradation by Burkholderia sp. FM-2 with Rhamnolipid: Mechanistic Insights from Cell Surface Properties and Transcriptomic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, Instruments and Bacterial Culture Conditions

2.1.1. Chemicals and Experimental Apparatus

2.1.2. Bacteria and Growth Conditions

2.2. Surface Tension of Rhamnolipid in MM

2.3. PHE Solubilisation Assay

2.4. PHE Degradation Experiments

2.5. Characterisation of Cell Surface Properties

2.5.1. Cell Surface Hydrophobicity and LPS Content

2.5.2. Zeta Potential Measurements

2.5.3. SEM Preparation

2.5.4. FT-IR Spectroscopic Determination

2.6. Extraction and PHE Degradation by Periplasmic, Cytoplasmic and Extracellular Enzymes

2.7. Transcriptome Response of Burkholderia sp. FM-2 to Rhamnolipid Treatment

2.7.1. RNA Purification and Transcriptome Sequencing

2.7.2. Real-Time Quantitative Fluorescence PCR (qRT-PCR) Validation Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

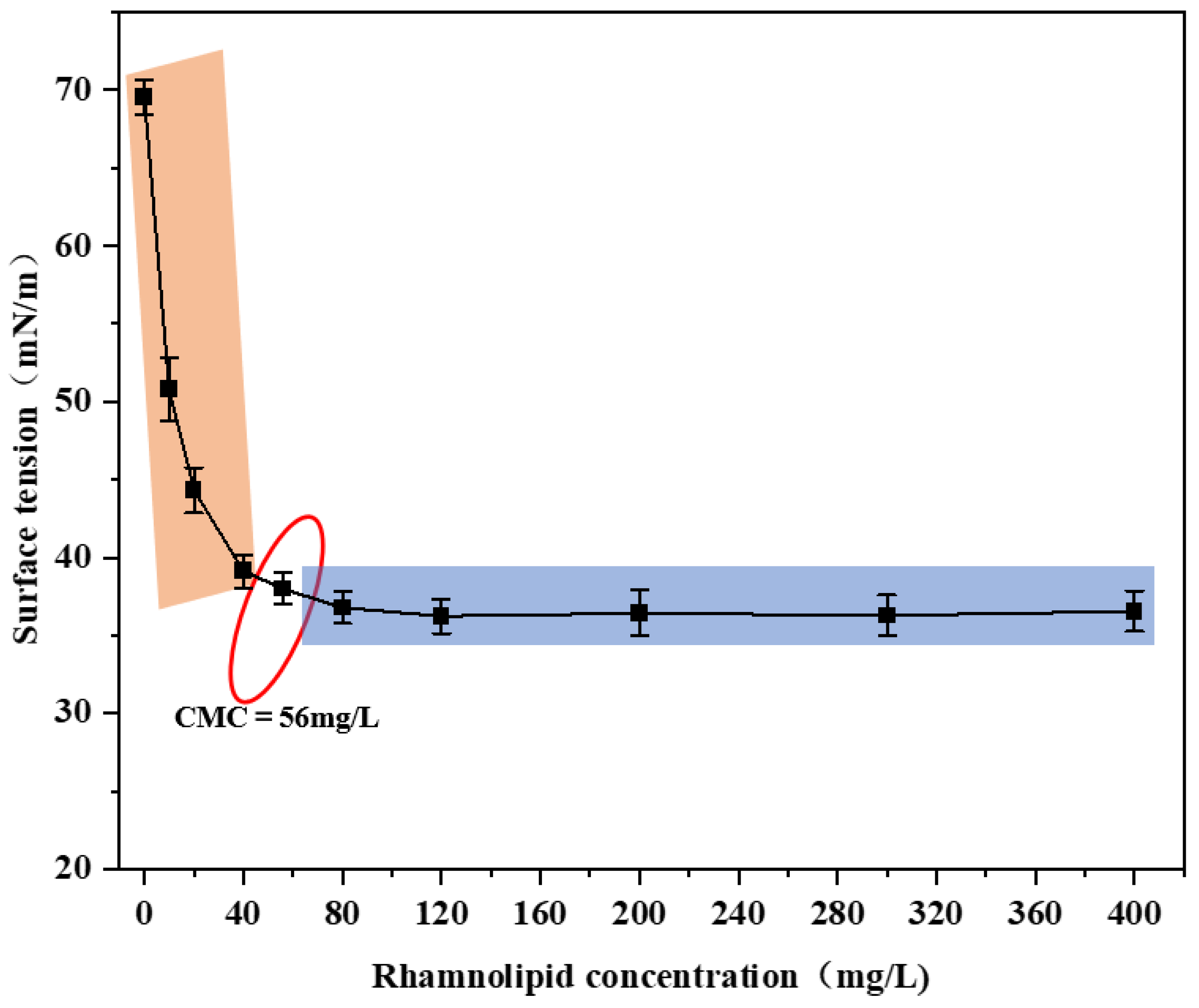

3.1. Critical Micelle Concentration of Rhamnolipids

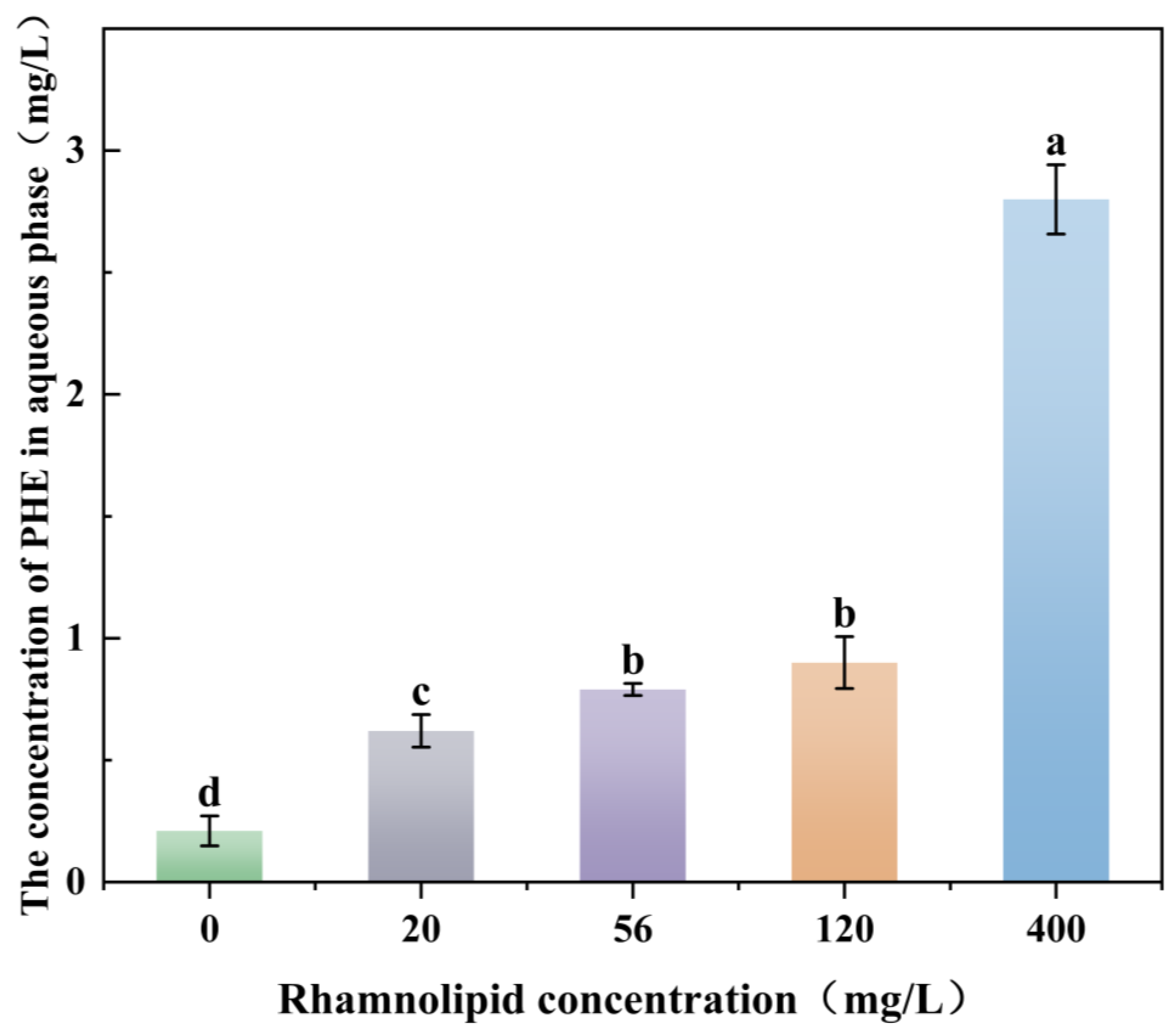

3.2. Effect of Rhamnolipid Concentration on Solubilisation of PHEs

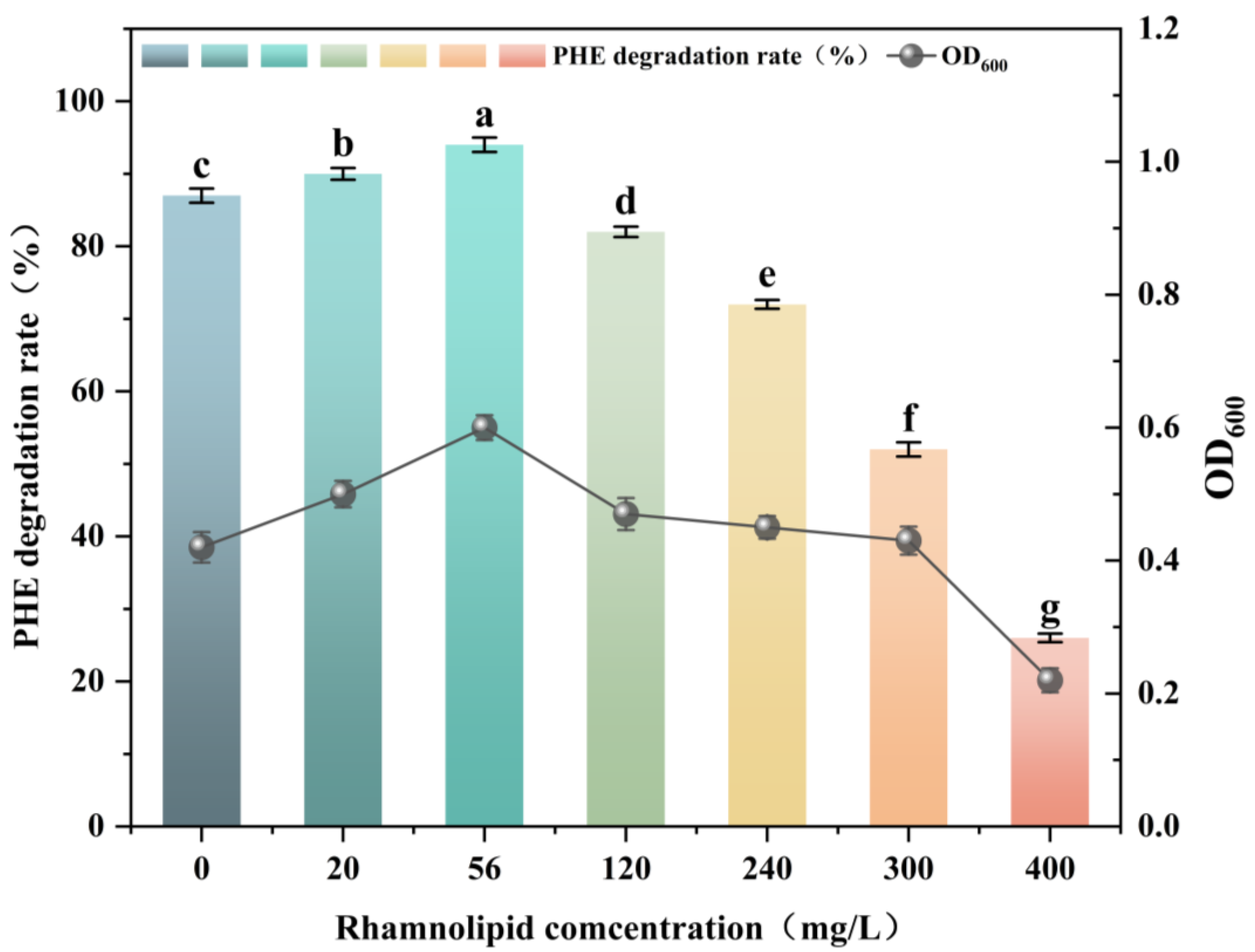

3.3. Effect of Rhamnolipids on PHE Biodegradation

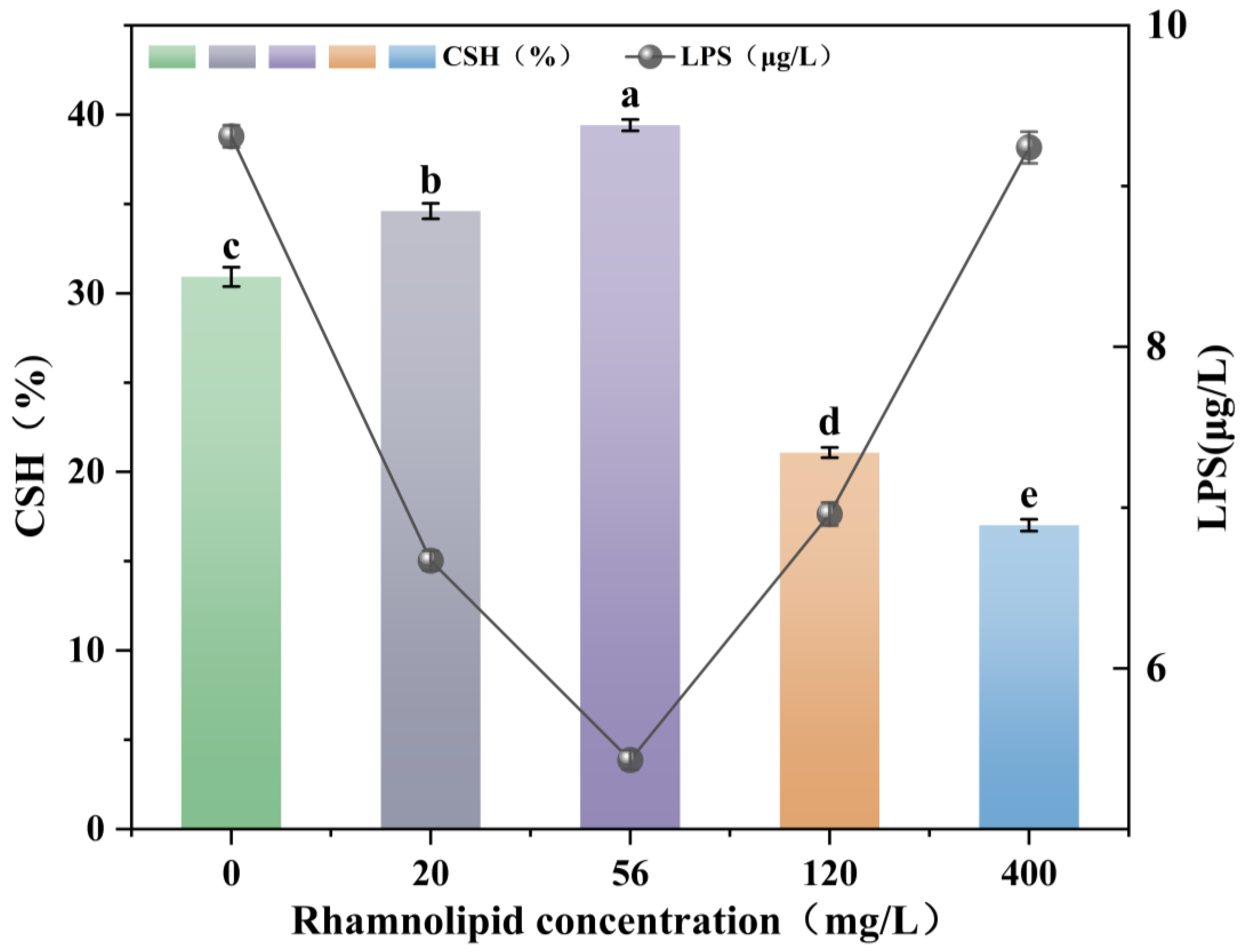

3.4. Effect of Rhamnolipids on Surface Hydrophobicity (CSH) and Release of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

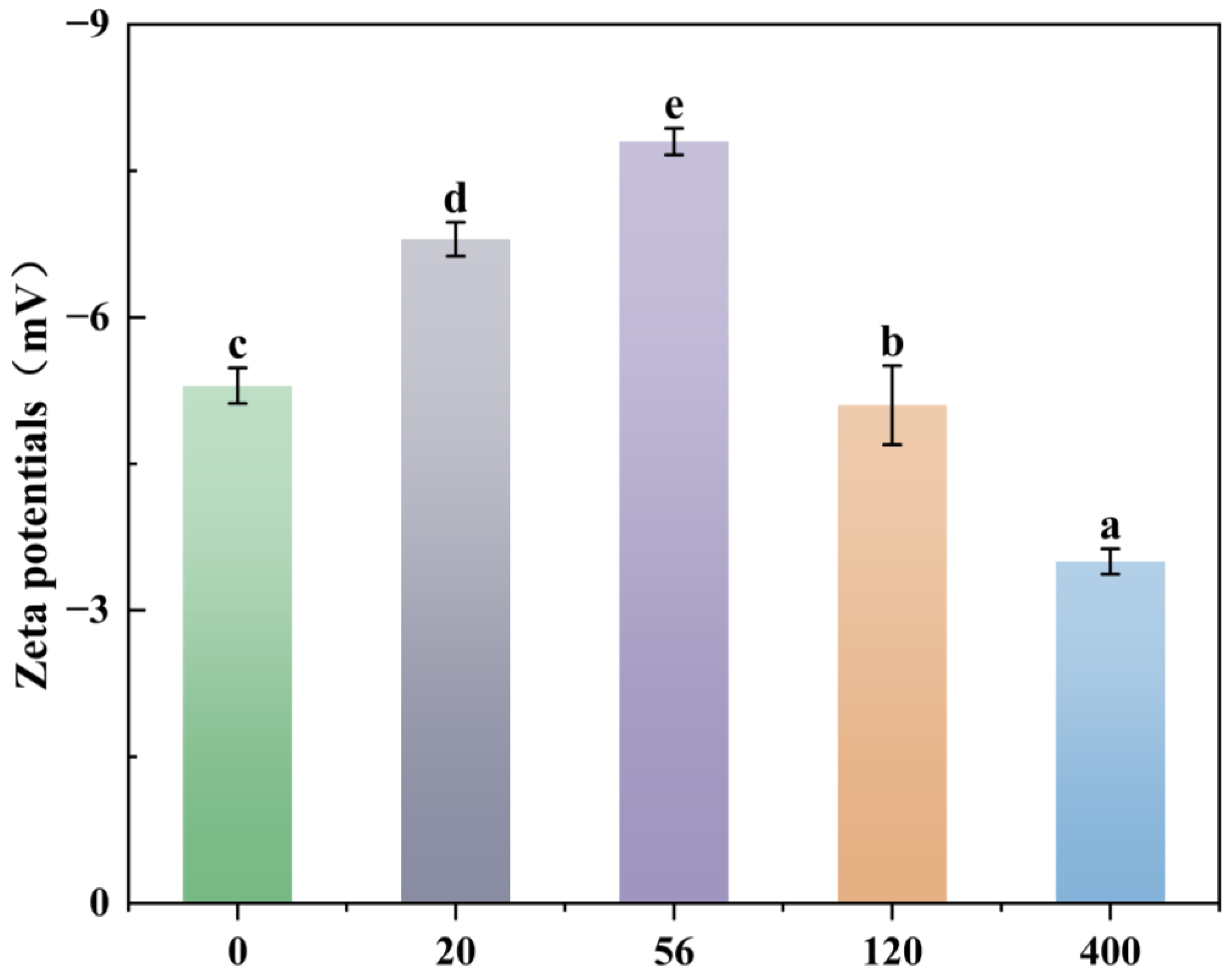

3.5. Effect of Rhamnolipids on Surface Zeta Potential of Burkholderia sp. FM-2 Cells

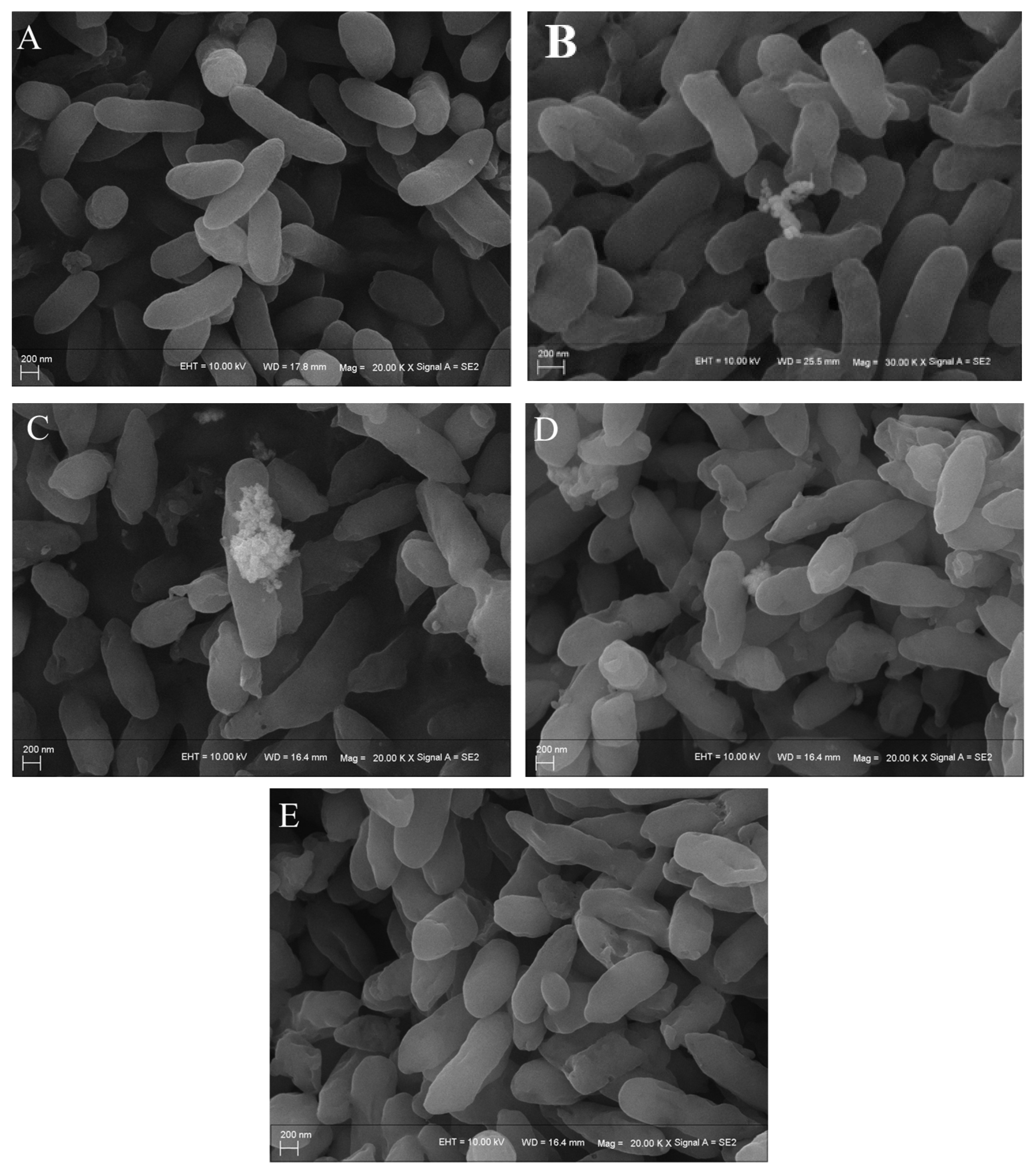

3.6. SEM Analysis

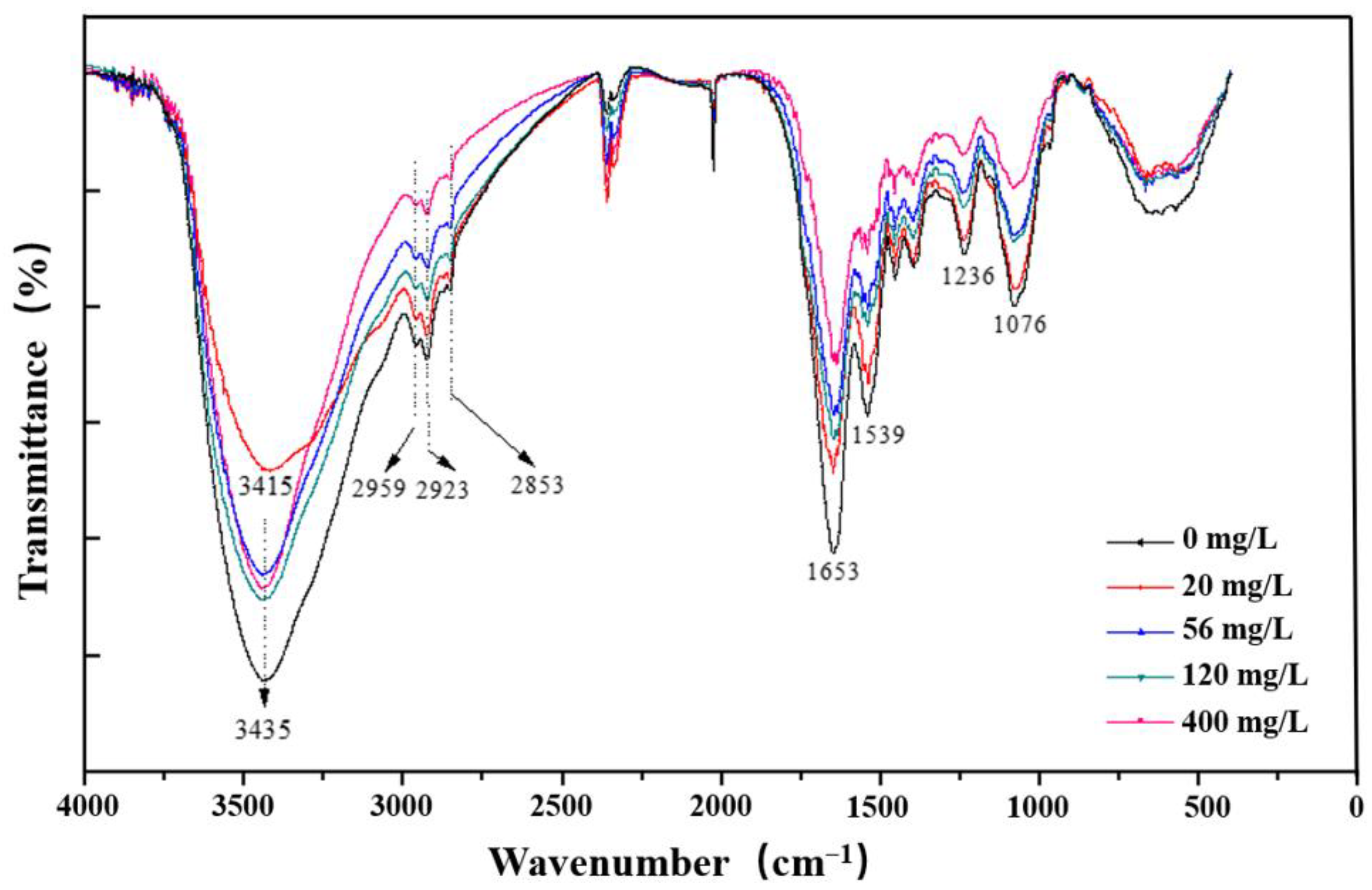

3.7. FT-IR Analysis

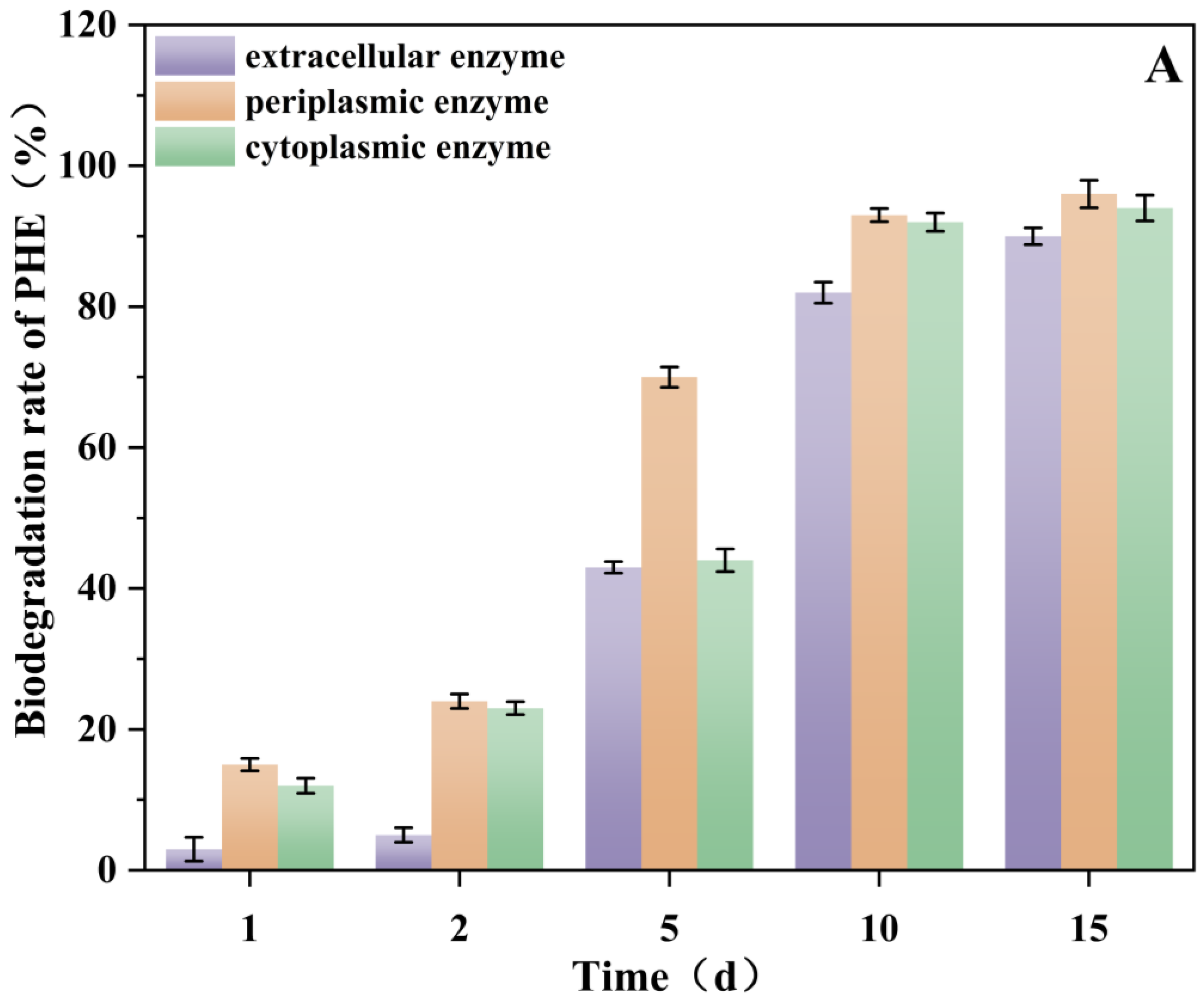

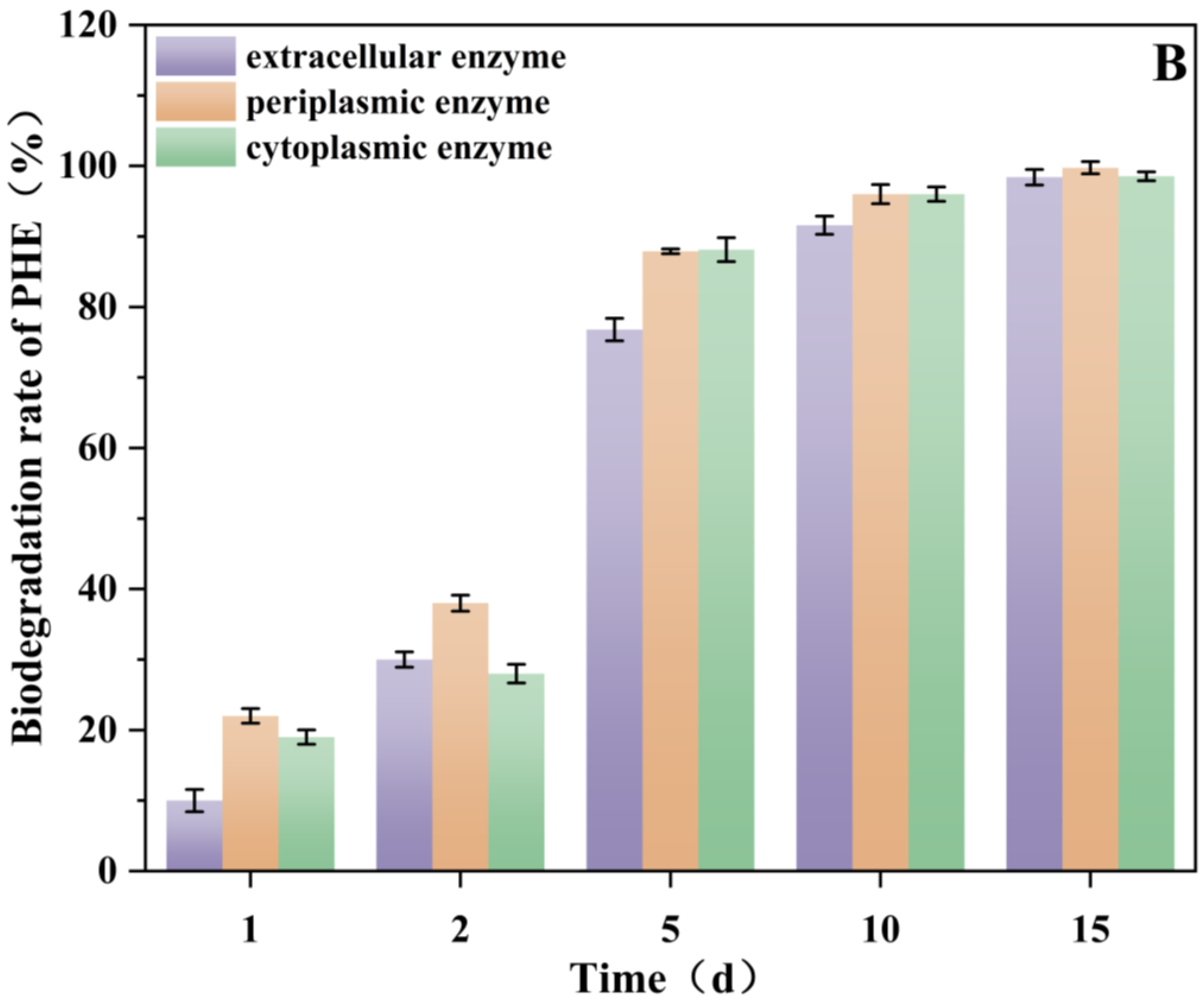

3.8. Effect of Rhamnolipids on Enzyme (Periplasmic, Cytoplasmic and Extracellular) Activities and Analysis of Enzyme Biodegradability

4. Transcriptome Response of Burkholderia sp. FM-2 to Rhamnolipid Treatment During Phenanthrene Biodegradation

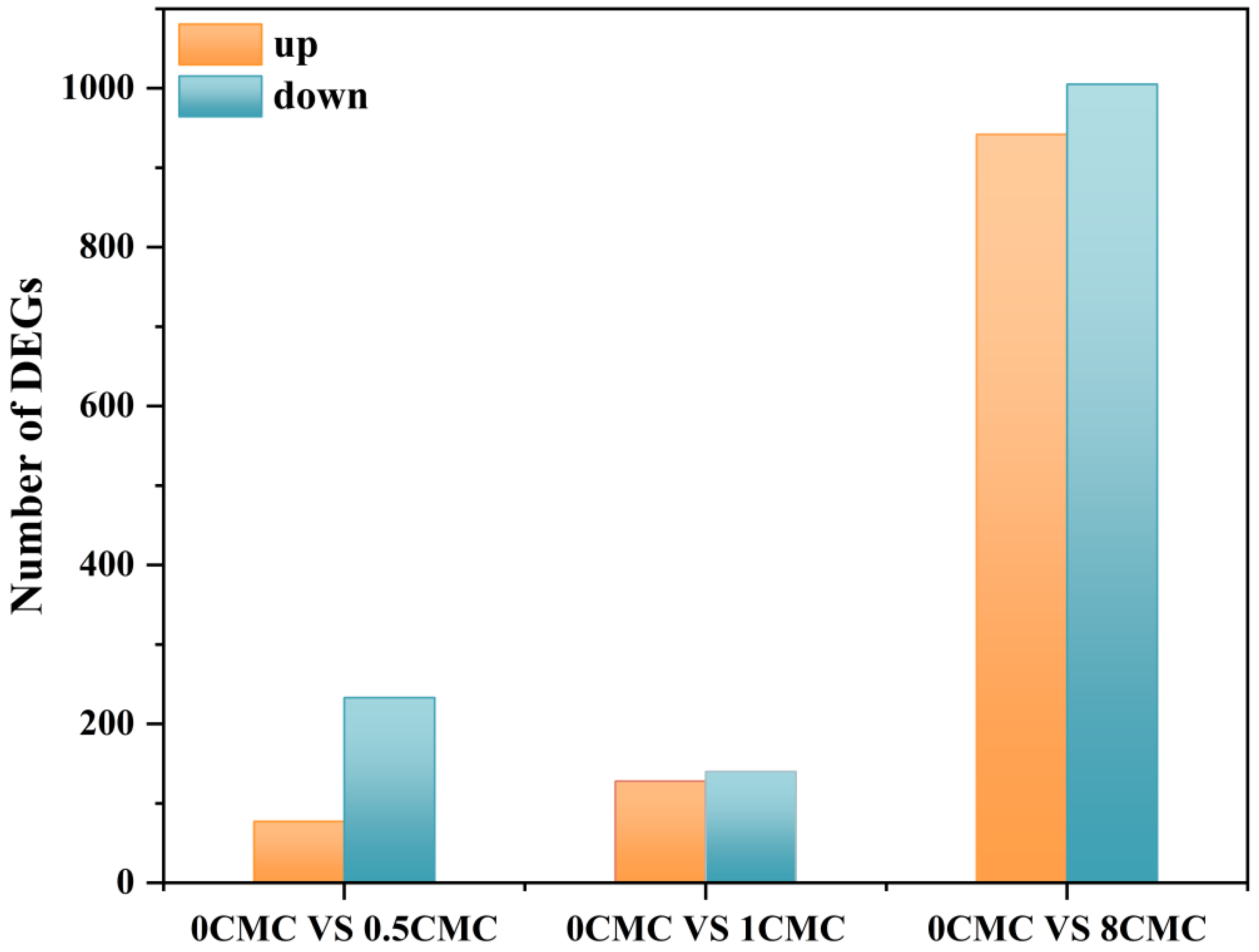

4.1. Burkholderia sp. FM-2 Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) Analysis

4.2. Functional Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

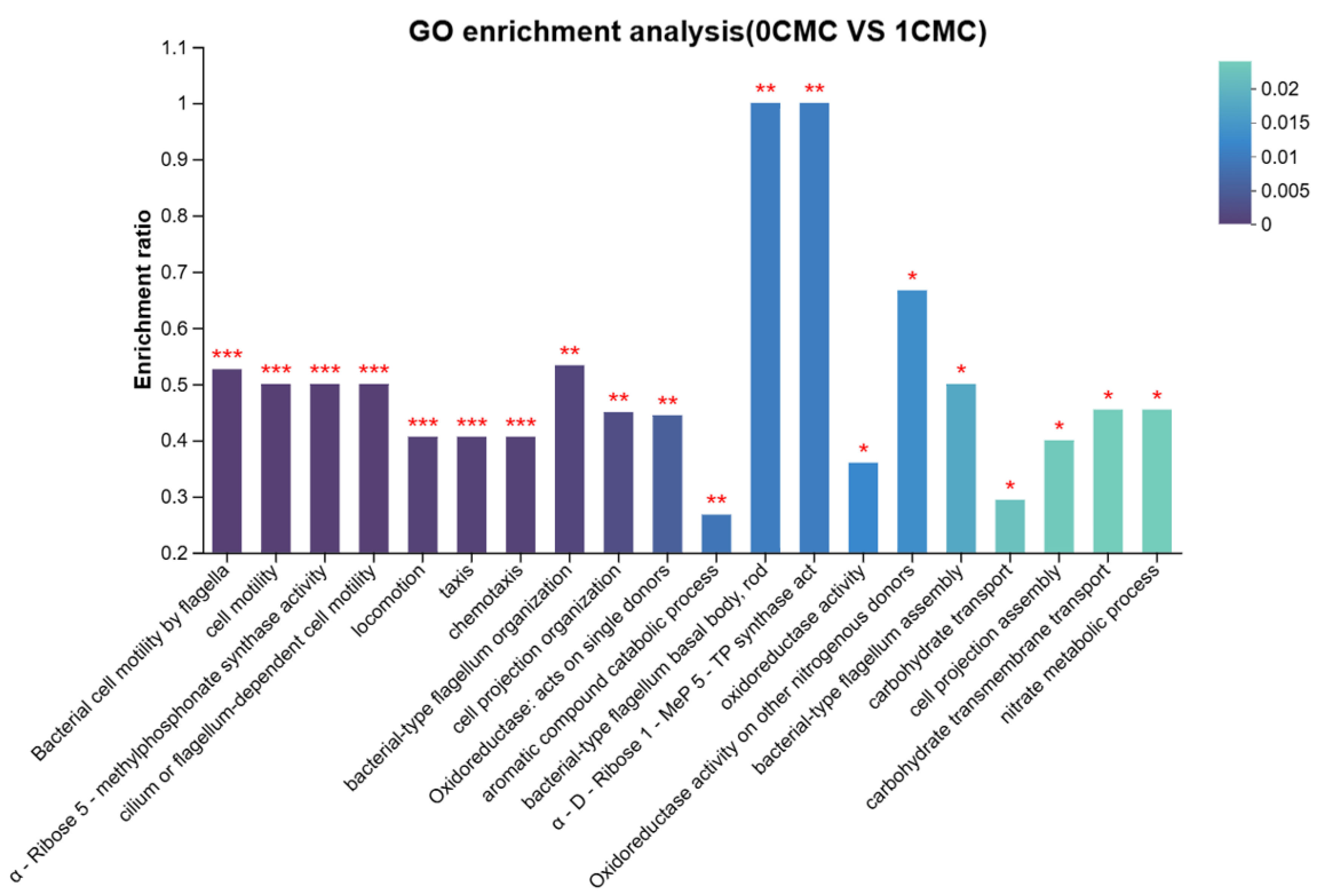

4.2.1. GO Functional Annotation Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

4.2.2. Gene Expression Associated with the Phenanthrene Degradation Pathway

4.2.3. Transporter System-Related Differentially Expressed Genes

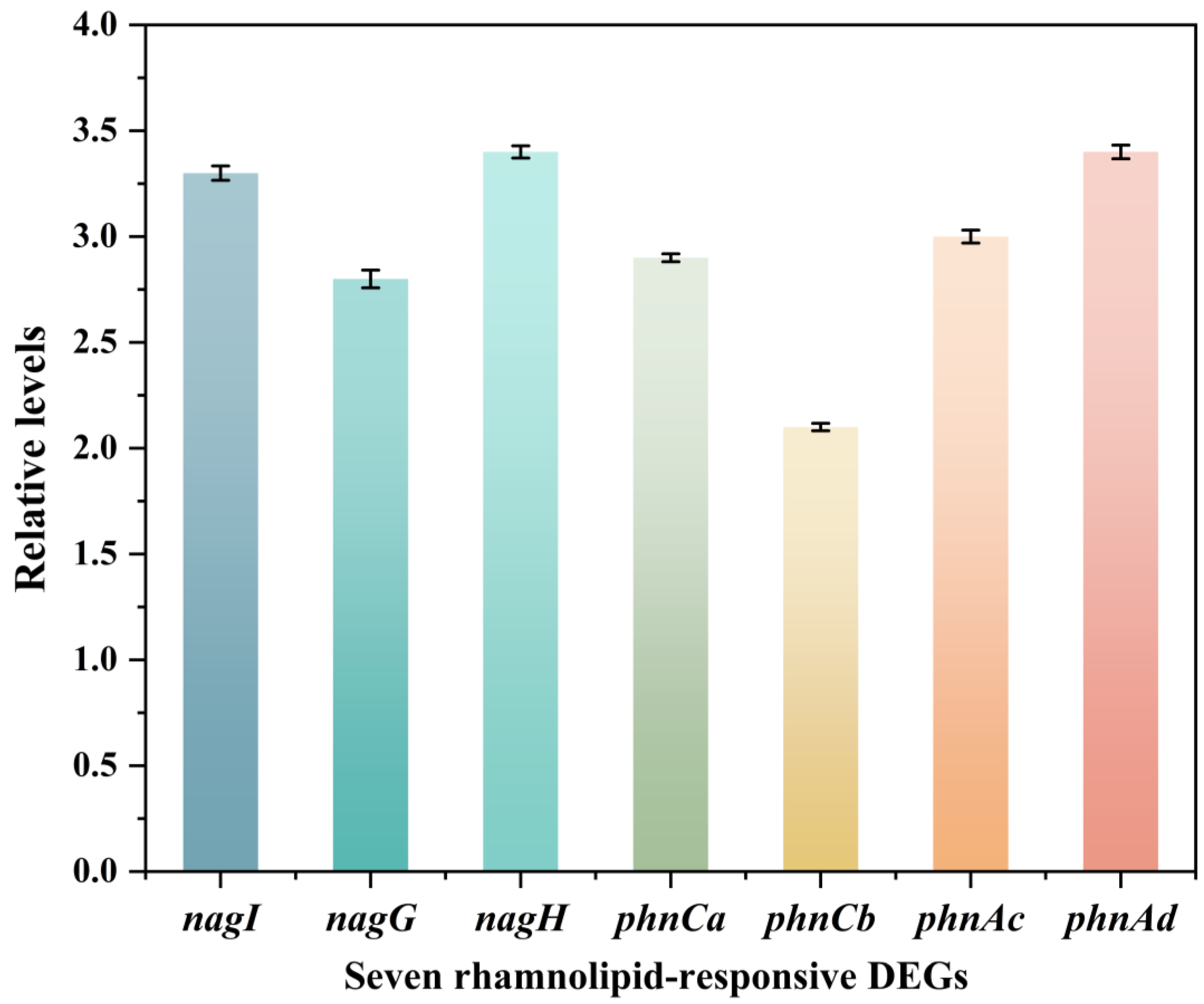

4.3. Validation of Differential Gene Expression via RT-qPCR

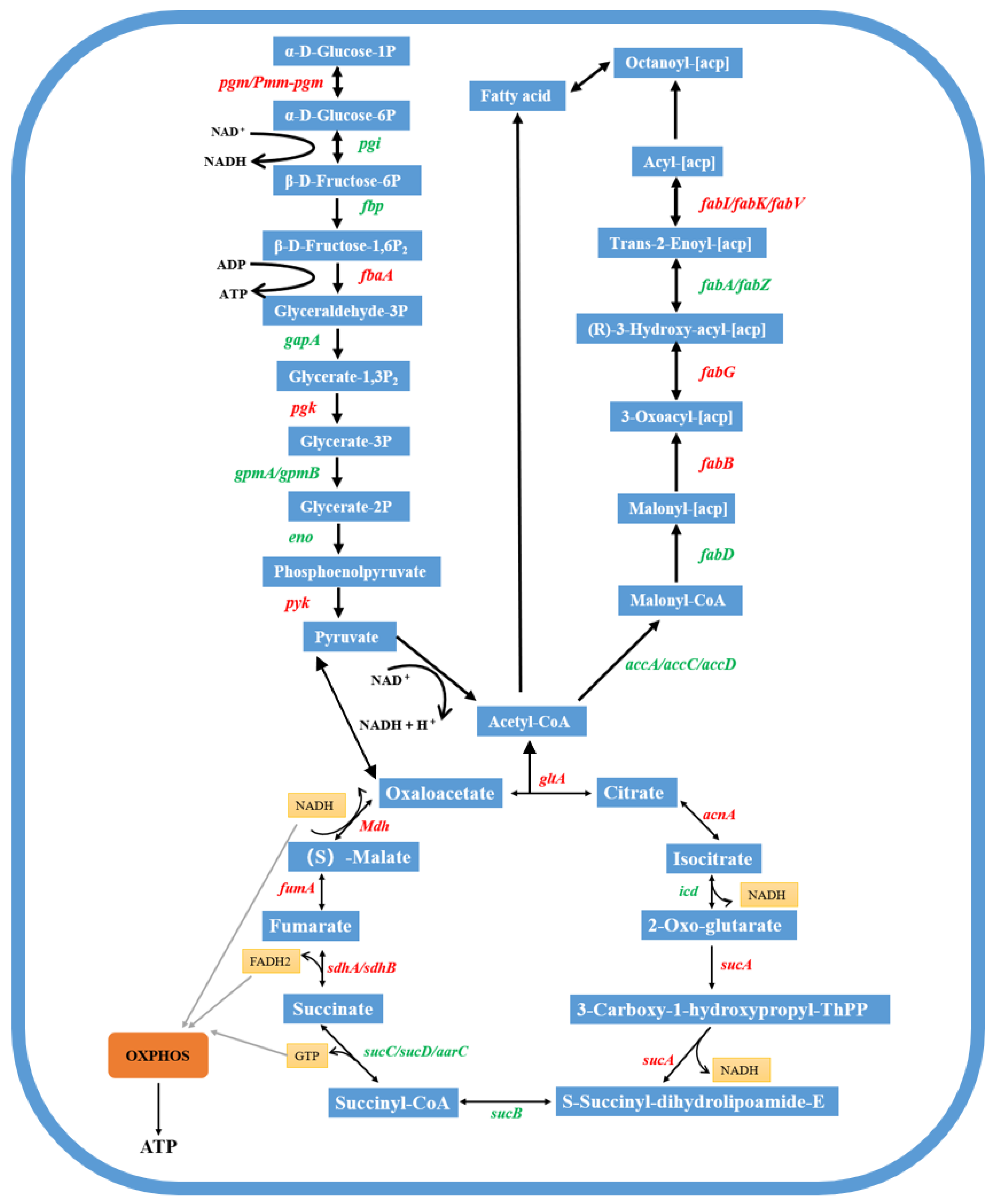

4.4. Response Patterns of Major Metabolic Pathways

4.4.1. Pyruvate Metabolism-Related Differential Gene Expression

4.4.2. Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle-Related Differentially Expressed Genes

4.4.3. Oxidative Phosphorylation-Related Differentially Expressed Genes

4.4.4. Metabolic Transcriptional Response in Strain FM-2

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, T.; Xu, J.; Xie, W.; Yao, Z.; Yang, H.; Sun, C.; Li, X. Pseudomonas aeruginosa L10: A Hydrocarbon-Degrading, Biosurfactant-Producing, and Plant-Growth-Promoting Endophytic Bacterium Isolated from a Reed (Phragmites australis). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Zeng, G.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, X.; He, X.; Lai, M.; He, Y. Role of Low-Concentration Monorhamnolipid in Cell Surface Hydrophobicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Adsorption or Lipopolysaccharide Content Variation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 10231–10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.W.C.; Fang, M.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Xing, B.S. Effect of Surfactants on Solubilization and Degradation of Phenanthrene under Thermophilic Conditions. J. Environ. Qual. 2004, 33, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.A.; Pedregosa, A.M.; Laborda, F. Biosurfactant-Mediated Biodegradation of Straight and Methyl-Branched Alkanes by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 55925. AMB Express 2011, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, H.; Xiao, R.; Zeng, G.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, M.; Lai, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, G.; et al. Mechanisms for Rhamnolipids-Mediated Biodegradation of Hydrophobic Organic Compounds. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S.; Devpura, N.; Jain, K.; Madamwar, D. Degradation of Chrysene by Enriched Bacterial Consortium. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhong, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Shao, B.; Liu, Z. Advances in Applications of Rhamnolipids Biosurfactant in Environmental Remediation: A Review. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 115, 796–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Liu, S.; Tong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, W.; Guo, C.; Xie, Y.; Lu, G.; Dang, Z. Effects of Rhamnolipids on the Cell Surface Characteristics of Sphingomonas sp. GY2B and the Biodegradation of Phenanthrene. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 24321–24330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.-H.; Zhan, X.-H.; Wang, S.-M.; Lin, Y.-S.; Zhou, L.-X. Effects of a Biosurfactant and a Synthetic Surfactant on Phenanthrene Degradation by a Sphingomonas strain. Pedosphere 2010, 20, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahseen, R.; Afzal, M.; Iqbal, S.; Shabir, G.; Khan, Q.M.; Khalid, Z.M.; Banat, I.M. Rhamnolipids and Nutrients Boost Remediation of Crude Oil-Contaminated Soil by Enhancing Bacterial Colonization and Metabolic Activities. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 115, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Huang, G.-H.; Xiao, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Combined Effects of DOM and Biosurfactant Enhanced Biodegradation of Polycylic Armotic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Soil–Water Systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 10536–10549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; Wang, S.; Abuduaini, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, Y. Rhamnolipid-Aided Biodegradation of Carbendazim by Rhodococcus sp. D-1: Characteristics, Products, and Phytotoxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 590–591, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacwa-Płociniczak, M.; Płaza, G.A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z.; Cameotra, S.S. Environmental Applications of Biosurfactants: Recent Advances. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Mulligan, C.N. Rhamnolipid Biosurfactant-Enhanced Soil Flushing for the Removal of Arsenic and Heavy Metals from Mine Tailings. Process Biochem. 2009, 44, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Cao, Y.; Pang, W.; Huang, J.; Guo, P.; Huang, L. Biodegradation of Phenanthrene and Heavy Metal Removal by Acid-Tolerant Burkholderia fungorum FM-2. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Yuan, X.; Liu, H.; Zeng, G.; Chen, X. Degradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) by Laccase in Rhamnolipid Reversed Micellar System. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 176, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppusamy, S.; Thavamani, P.; Singh, S.; Naidu, R.; Megharaj, M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Degradation Potential, Surfactant Production, Metal Resistance and Enzymatic Activity of Two Novel Cellulose-Degrading Bacteria Isolated from Koala Faeces. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.K.; Otzen, D.E. Folding of Outer Membrane Protein A in the Anionic Biosurfactant Rhamnolipid. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 1955–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourmentza, C.; Costa, J.; Azevedo, Z.; Servin, C.; Grandfils, C.; De Freitas, V.; Reis, M.A.M. Burkholderia thailandensis as a Microbial Cell Factory for the Bioconversion of Used Cooking Oil to Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Rhamnolipids. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, X.; Zeng, G.; Shi, J.; Chen, S. Effect of Biosurfactant on Cellulase and Xylanase Production by Trichoderma viride in Solid Substrate Fermentation. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 2347–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.-Q.; Lu, G.-N.; Dang, Z.; Yang, C.; Yi, X.-Y. A Phenanthrene-Degrading Strain Sphingomonas sp. GY2B Isolated from Contaminated Soils. Process Biochem. 2007, 42, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangchinda, C.; Pansri, R.; Wongwongsee, W.; Pinyakong, O. Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Biodegradation Potential in Mangrove Sediment from Don Hoi Lot, Samut Songkram Province, Thailand. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetibo, G.O.; Chien, M.-F.; Ikeda-Ohtsubo, W.; Suzuki, H.; Obayori, O.S.; Adebusoye, S.A.; Ilori, M.O.; Amund, O.O.; Endo, G. Biodegradation of Crude Oil and Phenanthrene by Heavy Metal Resistant Bacillus Subtilis Isolated from a Multi-Polluted Industrial Wastewater Creek. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 120, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.V.; Karegoudar, T.B.; Nayak, A.S. Mineralization of Phenanthrene by Paenibacillus sp. PRNK-6: Effect of Synthetic Surfactants on Its Mineralization. J. Microbiol. Virol. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, L.; Li, F. Influences and Mechanisms of Surfactants on Pyrene Biodegradation Based on Interactions of Surfactant with a Klebsiella oxytoca strain. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 142, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tahhan, R.A.; Sandrin, T.R.; Bodour, A.A.; Maier, R.M. Rhamnolipid-Induced Removal of Lipopolysaccharide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Effect on Cell Surface Properties and Interaction with Hydrophobic Substrates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3262–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasnezhad, H.; Gray, M.R.; Foght, J.M. Two Different Mechanisms for Adhesion of Gram-Negative Bacterium, Pseudomonas fluorescens LP6a, to an Oil-Water Interface. Colloid Surf. B—Biointerfaces 2008, 62, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Diwu, Z.; Nie, M.; Nie, H. Effects of Stress Metabolism on Physiological and Biochemical Reaction and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Degradation Ability of Bacillus. sp. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 195, 105909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Bao, M.; Sun, P.; Li, Y. Study on Bioadsorption and Biodegradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons by a Microbial Consortium. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 149, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Lin, W.; Wu, F.; Lu, G.; Lu, J.; Dang, Z. Comparative Transcriptomic Evidence for Tween80-Enhanced Biodegradation of Phenanthrene by Sphingomonas sp. GY2B. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Ma, J.; Huang, L.; Gao, G.; Zhao, Y.; Antunes, A.; Li, M. Study on the Mechanism by Which Fe3+ Promotes Toluene Degradation by Rhodococcus sp. TG-1. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantsyrnaya, T.; Blanchard, F.; Delaunay, S.; Goergen, J.L.; Guedon, E.; Guseva, E.; Boudrant, J. Effect of Surfactants, Dispersion and Temperature on Solubility and Biodegradation of Phenanthrene in Aqueous Media. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ayed, H.; Jemil, N.; Maalej, H.; Bayoudh, A.; Hmidet, N.; Nasri, M. Enhancement of Solubilization and Biodegradation of Diesel Oil by Biosurfactant from Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens An6. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 99, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornsunthorntawee, O.; Wongpanit, P.; Chavadej, S.; Abe, M.; Rujiravanit, R. Structural and Physicochemical Characterization of Crude Biosurfactant Produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa SP4 Isolated from Petroleum-Contaminated Soil. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1589–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pi, Y.; Bao, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y.; Sun, P.; Lu, J. Effect of Rhamnolipid Biosurfactant on Solubilization of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 101, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, R.S.; Rockne, K.J. Comparison of Synthetic Surfactants and Biosurfactants in Enhancing Biodegradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2003, 22, 2280–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, K.H.; Kim, K.W.; Seagren, E.A. Combined Effects of pH and Biosurfactant Addition on Solubilization and Biodegradation of Phenanthrene. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 65, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Liang, X.; Wu, F.; Dang, Z. Nonionic Surfactants Induced Changes in Cell Characteristics and Phenanthrene Degradation Ability of Sphingomonas sp. GY2B. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2016, 129, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrion, A.C.; Nakamura, J.; Shea, D.; Aitken, M.D. Screening Nonionic Surfactants for Enhanced Biodegradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Remaining in Soil After Conventional Biological Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 3838–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Zhu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhan, Y. Gene Expression of an Arthrobacter in Surfactant-Enhanced Biodegradation of a Hydrophobic Organic Compound. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3698–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhu, H.L. lux-Marked Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lipopolysaccharide Production in the Presence of Rhamnolipid. Colloid Surf. B Biointerfaces 2005, 41, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Selvam, A.; Wong, J.W.-C. Effects of Rhamnolipids on Cell Surface Hydrophobicity of PAH Degrading Bacteria and the Biodegradation of Phenanthrene. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3999–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, J.; Dick, R.P.; Li, H.; Shen, D.; Gao, Y.; Waigi, M.G.; Ling, W. Rhamnolipid Influences Biosorption and Biodegradation of Phenanthrene by Phenanthrene-Degrading Strain Pseudomonas sp. Ph6. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirova, A.; Spasova, D.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Galabova, D. Effects of Rhamnolipid-Biosurfactant on Cell Surface of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Res. 2009, 164, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Diwu, Z.; Nie, M.; Nie, H. Mechanism of Rhamnolipid Promoting the Degradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Gram-Positive Bacteria—Enhance Transmembrane Transport and Electron Transfer. J. Biotechnol. 2025, 397, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.Z.; Chen, J.; Lun, S.Y.; Wang, X.R. Influence of Biosurfactants Produced by Candida Antarctica on Surface Properties of Microorganism and Biodegradation of N-Alkanes. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4143–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, H.; Li, J.; Yuan, X.; Fu, H.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M. Effect of Monorhamnolipid on the Degradation of N-Hexadecane by Candida Tropicalis and the Association with Cell Surface Properties. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Splendiani, A.; Livingston, A.G.; Nicolella, C. Control of Membrane-Attached Biofilms Using Surfactants. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006, 94, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D.-T.; Chen, C.-L.; Chang, J.-S. Immobilization of Burkholderia sp. Lipase on a Ferric Silica Nanocomposite for Biodiesel Production. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 158, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotirova, A.V.; Spasova, D.I.; Galabova, D.N.; Karpenko, E.; Shulga, A. Rhamnolipid-Biosurfactant Permeabilizing Effects on Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacterial Strains. Curr. Microbiol. 2008, 56, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhay, P.C.; Rawat, P. Isolation of Alkaliphilic Bacterium Citricoccus alkalitolerans CSB1: An Efficient Biosorbent for Bioremediation of Tannery Waste Water. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2016, 62, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Peng, K.; Lu, L.; Wang, R.; Liu, J. Carbon Source Dependence of Cell Surface Composition and Demulsifying Capability of Alcaligenes sp. S-XJ-1. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 3056–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.H.; Jung, Y.; Yu, H.-W.; Chae, K.-J.; Kim, I.S. Physicochemical Interactions between Rhamnolipids and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Layers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3718–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Min, H. Characterization of a Multimetal Resistant Burkholderia fungorum Isolated from an E-Waste Recycling Area for Its Potential in Cd Sequestration. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Tong, M.; Sun, X.; Li, B. A Simple Method to Prepare Poly(Amic Acid)-Modified Biomass for Enhancement of Lead and Cadmium Adsorption. Biochem. Eng. J. 2007, 33, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zeng, G.; Zhong, H.; Yuan, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, G.; Li, J. Effects of Rhamnolipid on Degradation of Granular Organic Substrate from Kitchen Waste by a Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strain. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2007, 58, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.-M.; Shi, J.-G.; Yuan, X.-Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.-B.; Huang, G.-H.; Li, J.-B.; Xi, B.-D.; Liu, H.-L. Effects of Tween 80 and Rhamnolipid on the Extracellular Enzymes of Penicillium simplicissimum Isolated from Compost. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2006, 39, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deive, F.J.; Carvalho, E.; Pastrana, L.; Rúa, M.L.; Longo, M.A.; Sanroman, M.A. Strategies for Improving Extracellular Lipolytic Enzyme Production by Thermus thermophilus HB27. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3630–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahl, S.; Hofer, B. A Genetic System for the Rapid Isolation of Aromatic-Ring-Hydroxylating Dioxygenase Activities. Microbiology 2003, 149, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortall, K.; Djeghader, A.; Magner, E.; Soulimane, T. Insights into Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Enzymes: A Structural Perspective. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 659550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, D.C.; Johnson, E.; Lewinson, O. ABC Transporters: The Power to Change. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobbett, C.S.; Meagher, R.B. Arabidopsis and the Genetic Potential for the Phytoremediation of Toxic Elemental and Organic Pollutants. Arab. Book 2002, 1, e0032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikkema, J.; De Bont, J.A.; Poolman, B. Mechanisms of Membrane Toxicity of Hydrocarbons. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 59, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendz, G.L.; Ball, G.E.; Meek, D.J. Pyruvate Metabolism in Campylobacter spp. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 1997, 1334, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mu, J.; Chen, D.; Han, F.; Xu, H.; Kong, F.; Xie, F.; Feng, B. Production of Biomass and Lipid by the Microalgae Chlorella protothecoides with Heterotrophic-Cu(II) Stressed (HCuS) Coupling Cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 148, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, R.A.; Aggeler, R. Mechanism of the F1F0-Type ATP Synthase, a Biological Rotary Motor. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002, 27, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhai, Y.; Ma, J.; Gao, G.; Cui, Y.; Ying, M.; Zhao, Y.; Antunes, A.; Huang, L.; Li, M. Enhancing Phenanthrene Degradation by Burkholderia sp. FM-2 with Rhamnolipid: Mechanistic Insights from Cell Surface Properties and Transcriptomic Analysis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112608

Zhai Y, Ma J, Gao G, Cui Y, Ying M, Zhao Y, Antunes A, Huang L, Li M. Enhancing Phenanthrene Degradation by Burkholderia sp. FM-2 with Rhamnolipid: Mechanistic Insights from Cell Surface Properties and Transcriptomic Analysis. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112608

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhai, Ying, Jiajun Ma, Guohui Gao, Yumeng Cui, Ming Ying, Yihe Zhao, Agostinho Antunes, Lei Huang, and Meitong Li. 2025. "Enhancing Phenanthrene Degradation by Burkholderia sp. FM-2 with Rhamnolipid: Mechanistic Insights from Cell Surface Properties and Transcriptomic Analysis" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112608

APA StyleZhai, Y., Ma, J., Gao, G., Cui, Y., Ying, M., Zhao, Y., Antunes, A., Huang, L., & Li, M. (2025). Enhancing Phenanthrene Degradation by Burkholderia sp. FM-2 with Rhamnolipid: Mechanistic Insights from Cell Surface Properties and Transcriptomic Analysis. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112608