Xylo-Oligosaccharide Production from Wheat Straw Xylan Catalyzed by a Thermotolerant Xylanase from Rumen Metagenome and Assessment of Their Probiotic Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene Cloning and Expression Plasmid Construction

2.2. Sequence Analysis

2.3. Expression of RuXyn394

2.4. Characterization of RuXyn854

2.5. XOS Production and Assay

2.6. In Vitro Fermentation of XOS

2.7. Enzyme Assays

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sequence Analysis and Production of RuXyn854

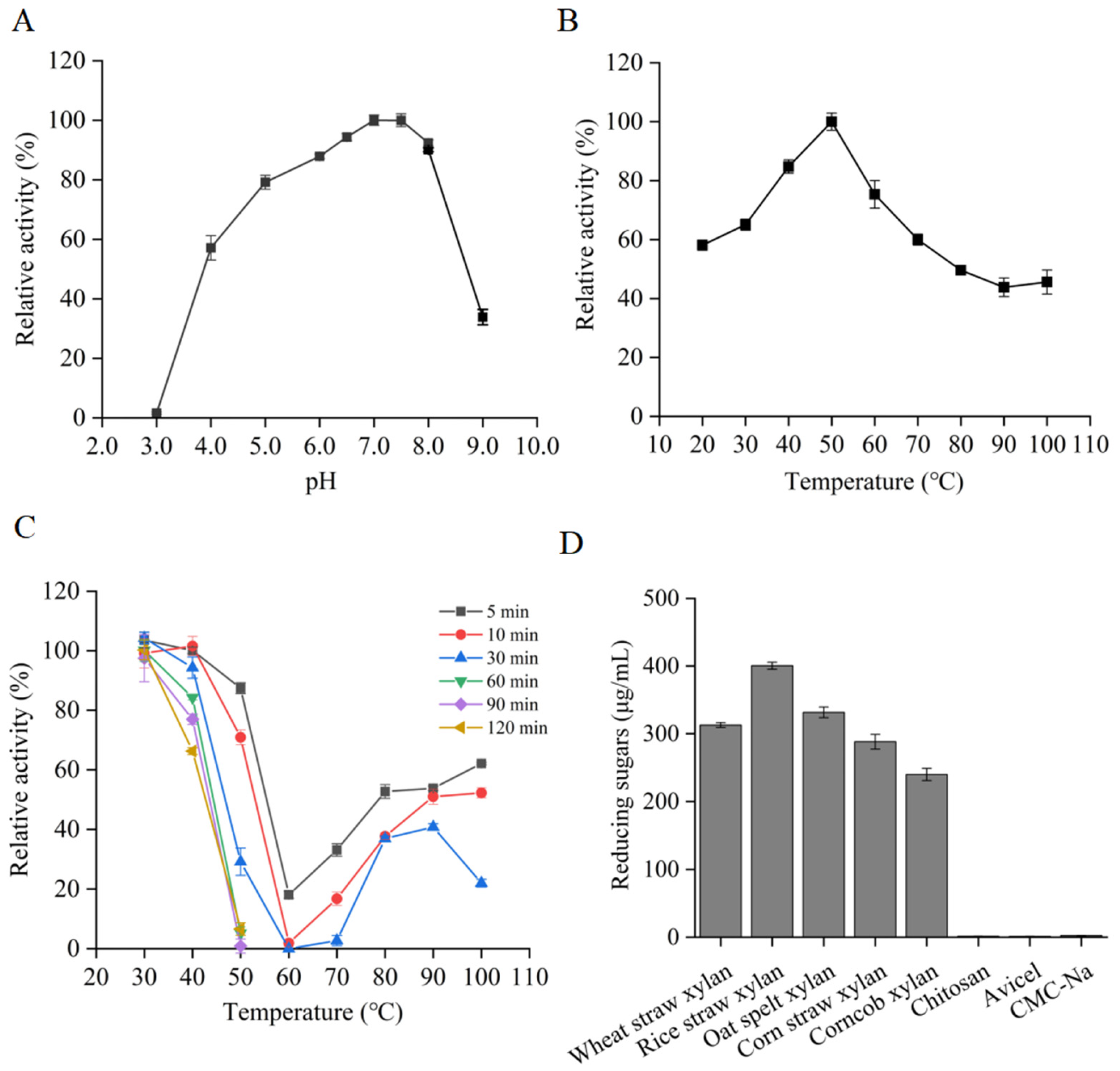

3.2. Expression and Characteristics of RuXyn854

3.3. Production and Assay of XOS

3.4. In Vitro Fermentation of XOSs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Ajuwon, K.M.; Zhong, R.; Li, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Beckers, Y.; Everaert, N. Xylo-oligosaccharides, preparation and application to human and animal health: A review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 731930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Yin, J.; Li, L.; Luan, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Li, S. Prebiotic potential of xylooligosaccharides derived from corn cobs and their in vitro antioxidant activity when combined with Lactobacillus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Li, H.; Sun, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. Effect of Arabinoxylan and Xylo-Oligosaccharide on Growth Performance and Intestinal Barrier Function in Weaned Piglets. Animals 2023, 13, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, C.; Yaqoob, P.; Gibson, G.; Rastall, R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised crossover study to determine the effects of a prebiotic, a probiotic and a synbiotic upon the gut microbiota and immune response of healthy volunteers. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, E239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.H.; Frøkiær, H.; Christensen, A.G.; Bergström, A.; Licht, T.R.; Hansen, A.K.; Metzdorff, S.B. Dietary xylooligosaccharide downregulates IFN-γ and the low-grade inflammatory cytokine IL-1β systemically in mice. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Sohail, M. Xylanolytic Bacillus species for xylooligosaccharides production: A critical review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.F.A.; de Oliva Neto, P.; Da Silva, D.F.; Pastore, G.M. Xylo-oligosaccharides from lignocellulosic materials: Chemical structure, health benefits and production by chemical and enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lei, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Qiu, Q.; Li, Y.; Song, X.; Xiong, X.; Zang, Y.; Qu, M. Production of xylo-oligosaccharides with degree of polymerization 3–5 from wheat straw xylan by a xylanase derived from rumen metagenome and utilization by probiotics. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares-Diestra, K.K.; de Souza Vandenberghe, L.P.; Vieira, S.; Goyzueta-Mamani, L.D.; de Mattos, P.B.G.; Manzoki, M.C.; Soccol, V.T.; Soccol, C.R. The potential of xylooligosaccharides as prebiotics and their sustainable production from agro-industrial by-products. Foods 2023, 12, 2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Menezes, C.R.; Silva, Í.S.; Pavarina, É.C.; Dias, E.F.; Dias, F.G.; Grossman, M.J.; Durrant, L.R. Production of xylooligosaccharides from enzymatic hydrolysis of xylan by the white-rot fungi Pleurotus. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2009, 63, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapla, D.; Pandit, P.; Shah, A. Production of xylooligosaccharides from corncob xylan by fungal xylanase and their utilization by probiotics. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 115, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Sutradhar, S.; Baishya, D. Delineating thermophilic xylanase from Bacillus licheniformis DM5 towards its potential application in xylooligosaccharides production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullón, P.; Moura, P.; Esteves, M.P.; Girio, F.M.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J.C. Assessment on the fermentability of xylooligosaccharides from rice husks by probiotic bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7482–7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleghipour, L.; Linares-Pastén, J.A.; Rashedi, H.; Ranaei Siadat, S.O.; Jasilionis, A.; Al-Hamimi, S.; Sardari, R.R.; Karlsson, E.N. Extraction of sugarcane bagasse arabinoxylan, integrated with enzymatic production of xylo-oligosaccharides and separation of cellulose. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Veizaga, D.M.; Villagomez, R.; Linares-Pastén, J.A.; Carrasco, C.; Álvarez, M.T.; Adlercreutz, P.; Nordberg Karlsson, E. Extraction of glucuronoarabinoxylan from quinoa stalks (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) and evaluation of xylooligosaccharides produced by GH10 and GH11 xylanases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8663–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M.; Alonso, J.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J. Enzymatic processing of crude xylooligomer solutions obtained by autohydrolysis of eucalyptus wood. Food Biotechnol. 2002, 16, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinger, L.; Forsberg, C.; Cheng, K.-J. The rumen: A unique source of enzymes for enhancing livestock production. Anaerobe 1996, 2, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Pan, K.; Ouyang, K.; Song, X.; Xiong, X.; Qu, M.; Zhao, X. Characteristics of recombinant xylanase from camel rumen metagenome and its effects on wheat bran hydrolysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadikolaei, K.K.; Sangachini, E.D.; Vahdatirad, V.; Noghabi, K.A.; Zahiri, H.S. An extreme halophilic xylanase from camel rumen metagenome with elevated catalytic activity in high salt concentrations. Amb Express 2019, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Zhao, X. Characterization of a new xylanase found in the rumen metagenome and its effects on the hydrolysis of wheat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6493–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.; Qi, M.; Ha, J.; Forsberg, C. Fibrobacter succinogenes, a dominant fibrolytic ruminal bacterium: Transition to the post genomic era. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 20, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Chan, H.; Lin, H.T.; Shyu, Y.T. Production, purification and characterisation of a novel halostable xylanase from Bacillus sp. NTU-06. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2010, 156, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Kawarabayasi, Y.; Miyazaki, K.; Satyanarayana, T. Cloning, expression and characteristics of a novel alkalistable and thermostable xylanase encoding gene (Mxyl) retrieved from compost-soil metagenome. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e52459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Chang, S.; Gao, Z.; Ma, J.; Wu, B.; He, B.; Wei, P. Identification and characterization of a thermostable GH11 xylanase from Paenibacillus campinasensis NTU-11 and the distinct roles of its carbohydrate-binding domain and linker sequence. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 209, 112167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Qiu, H.; Li, K.; Luo, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, N.; He, H. Heterologous expression in Pichia pastoris and characterization of a novel GH11 xylanase from saline-alkali soil with excellent tolerance to high pH, high salt concentrations and ethanol. Protein Expr. Purif. 2017, 139, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, Z.L.; Li, Y.H. Enzymatic characterization and thermostability improvement of an acidophilic endoxylanase PphXyn11 from Paenibacillus physcomitrellae XB. Protein Expr. Purif. 2024, 219, 106482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, P.R.; Bauermeister, A.; Ribeiro, L.F.; Messias, J.M.; Almeida, P.Z.; Moraes, L.A.; Vargas-Rechia, C.G.; De Oliveira, A.H.; Ward, R.J.; Kadowaki, M.K.; et al. GH11 xylanase from Aspergillus tamarii Kita: Purification by one-step chromatography and xylooligosaccharides hydrolysis monitored in real-time by mass spectrometry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, J.-J.; Ren, W.-Z.; Lin, L.-B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhi, X.-Y.; Tang, S.-K.; Li, W.-J. Cloning, expression, and characterization of an alkaline thermostable GH11 xylanase from Thermobifida halotolerans YIM 90462T. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 39, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Shao, W. Cloning, expression and characterization of glycoside hydrolase family 11 endoxylanase from Bacillus pumilus ARA. Biotechnol. Lett. 2011, 33, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Lei, X.; Ouyang, K.; Wang, L.; Qiu, Q.; Li, Y.; Zang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, X. A Glycosyl Hydrolase 30 Family Xylanase from the Rumen Metagenome and Its Effects on In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Wheat Straw. Animals 2023, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavarina, G.C.; Lemos, E.G.; Lima, N.S.; Pizauro, J.M., Jr. Characterization of a new bifunctional endo-1 2021, 4-β-xylanase/esterase found in the rumen metagenome. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Tang, S.; Mi, S.; Jia, X.; Peng, X.; Han, Y. Biochemical characterization of a novel thermostable GH11 xylanase with CBM6 domain from Caldicellulosiruptor kronotskyensis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2014, 107, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Huang, J.; Yin, Y.; Ding, S. A novel neutral xylanase with high SDS resistance from Volvariella volvacea: Characterization and its synergistic hydrolysis of wheat bran with acetyl xylan esterase. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 40, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, C.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Fan, G.; Xiong, K.; Yang, R.; Zhang, C.; Ma, R. Improving the thermostability and catalytic efficiency of GH11 xylanase PjxA by adding disulfide bridges. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 128, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandeparkar, R.; Bhosle, N.B. Purification and characterization of thermoalkalophilic xylanase isolated from the Enterobacter sp. MTCC 5112. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, P.O.; de Alencar Guimaraes, N.C.; Serpa, J.D.; Masui, D.C.; Marchetti, C.R.; Verbisck, N.V.; Zanoelo, F.F.; Ruller, R.; Giannesi, G.C. Application of an endo-xylanase from Aspergillus japonicus in the fruit juice clarification and fruit peel waste hydrolysis. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monclaro, A.V.; Recalde, G.L.; da Silva, F.G., Jr.; de Freitas, S.M.; Ferreira Filho, E.X. Xylanase from Aspergillus tamarii shows different kinetic parameters and substrate specificity in the presence of ferulic acid. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2019, 120, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooshima, H.; Sakata, M.; Harano, Y. Enhancement of enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose by surfactant. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1986, 28, 1727–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Jayapal, N.; Kolte, A.; Senani, S.; Sridhar, M.; Dhali, A.; Suresh, K.; Jayaram, C.; Prasad, C. Process for enzymatic production of xylooligosaccharides from the xylan of corn cobs. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azelee, N.I.W.; Jahim, J.M.; Ismail, A.F.; Fuzi, S.F.Z.M.; Rahman, R.A.; Illias, R.M. High xylooligosaccharides (XOS) production from pretreated kenaf stem by enzyme mixture hydrolysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 81, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilad, O.; Jacobsen, S.; Stuer-Lauridsen, B.; Pedersen, M.B.; Garrigues, C.; Svensson, B. Combined transcriptome and proteome analysis of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12 grown on xylo-oligosaccharides and a model of their utilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 7285–7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khangwal, I.; Skariyachan, S.; Uttarkar, A.; Muddebihalkar, A.G.; Niranjan, V.; Shukla, P. Understanding the xylooligosaccharides utilization mechanism of Lactobacillus brevis and Bifidobacterium adolescentis: Proteins involved and their conformational stabilities for effectual binding. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022, 64, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, P.; Barata, R.; Carvalheiro, F.; Gírio, F.; Loureiro-Dias, M.C.; Esteves, M.P. In vitro fermentation of xylo-oligosaccharides from corn cobs autohydrolysis by Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus strains. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, T. Efficient secretion of xylanase in Escherichia coli for production of prebiotic xylooligosaccharides. LWT 2022, 162, 113481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, M.; Fujikawa, S.; Matsumoto, N. Effect of xylooligosaccharide on the growth of bifidobacteria. Bifidobact. Microflora 1990, 9, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliev, I.; Vasileva, T.; Bivolarski, V.; Momchilova, A.; Ivanova, I. Metabolic profiling of xylooligosaccharides by Lactobacilli. Polymers 2020, 12, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisseri, C.; Gudipati, M. Bioactive xylo-oligosaccharides from wheat bran soluble polysaccharides. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Xylanase (Source) | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Topt, pHopt | Thermostability (% Residual Activity, Maximum Temperature, Time) | Kinetic Values (Temperature, Substrate) | Hydrolysis Products (Substrate) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CrXyn (rumen metagenome) | 38 | 40 °C, 7.0 | Inactivation, 70 °C, 30 min | Km 5.98 g/L (40 °C, wheat straw xylan) | X1 (10.5%), X2 (58.1%), X3 (21.0%), X4 (5.3%), X5 (5.2%) from wheat straw xylan | [18] |

| XylCMS (rumen) | 47 | 55 °C, 6.0 | >80%, 60 °C, 10 min | Km 23.3 g/L, kcat 1383 s−1 (55 °C, oat spelt xylan) | X4 from oat spelt xylan | [19] |

| XynNTU (Paenibacillus campinasensis) | 41 | 60 °C, 7.0 | <10%, 80 °C, 3 h | Km 8.35 g/L (60 °C, oat spelt xylan) | X2, X3, X5 from beech-wood xylan | [24] |

| rMxyl (compost–soil metagenome) | 40 | 80 °C, 9.0 | 50%, 90 °C, 15 min | Km 8.0 g/L (80 °C, birchwood xylan) | X1, X2, X3 from wheat bran | [23] |

| Xyn11-1 (saline–alkali soil) | 27 | 50 °C, 6.0 | 23.7%, 50 °C, 5 min | Km 3.7 g/L, kcat 42.1 s−1 (50 °C, birchwood xylan) | X4, X5 from birchwood xylan | [25] |

| PphXyn11 (Paenibacillus physcomitrellae) | 20.2 | 40 °C, 3.0–4.0 | Near-inactivation, 50–80 °C, 1 h | Km 13.8 g/L, 149.34 s−1 (40 °C, birchwood xylan) | X2, X3 from X4, X5, and X6 | [26] |

| xylanase (Aspergillus tamari) | 19.5 | 60 °C, 5.5 | Inactivation, 60 °C, 30 min | Km 7.9 g/L, 408.2 s−1 (60 °C, birchwood xylan) | X2, X3, and X4 from birchwood xylan | [27] |

| Thxyn11A (Thermobifida halotolerans) | 34 | 70 °C, 9.0 | <10%, 90 °C, 30 min | Km 3.5 g/L (70 °C, birchwood xylan) | X3, X4, X5 from birchwood xylan | [28] |

| Bpu XynA (Bacillus pumilus) | 23 | 50 °C, 6.6 | >80%, 65 °C, 10 min | Km 5.53 g/L, 56.07 s−1 (60 °C, oat spelt xylan) | X1 (trace amount), X2, X3, X4 from oat spelt xylan | [29] |

| RuXyn854 (rumen metagenome) | 53 | 50 °C, 7.0 | 52%, 100 °C, 10 min | Km 150.1 g/L, 416.1 s−1 (50 °C, wheat straw xylan) | X1 (trace amount), X2, X3, X4, X5 from wheat straw xylan | This study |

| Substrates | Km (mg mL−1) | Vmax (μmol min−1 mg−1) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (mL mg−1 s−1) | Specific Activity (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice straw xylan | 103.3 | 559.1 | 493.9 | 4.78 | 353.5 |

| Wheat straw xylan | 150.1 | 471.0 | 416.1 | 2.77 | 276.9 |

| Corn straw xylan | 150.0 | 449.6 | 397.2 | 2.65 | 252.2 |

| Corn cob xylan | 49.7 | 119.0 | 105.1 | 2.12 | 208.8 |

| Reagents | Concentration | Relative Activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SDS | 1 mM | 99.0 ± 1.2 |

| 5 mM | 75.2 ± 3.0 | |

| Dithiothreitol | 1 mM | 111.7 ± 5.2 |

| 5 mM | 111.7 ± 1.2 | |

| EDTA-Na | 1 mM | 58.8 ± 3.5 |

| 5 mM | 64.3 ± 6.1 | |

| β-mercaptoethanol | 1 mM | 100.2 ± 3.4 |

| 5 mM | 97.5 ± 1.7 | |

| Tween-20 | 0.05% (v/v) | 115.3 ± 5.5 |

| 0.25% (v/v) | 119.7 ± 1.8 | |

| Triton X-100 | 0.05% (v/v) | 117.7 ± 2.6 |

| 0.25% (v/v) | 125.5 ± 8.7 | |

| Methanol | 5% (v/v) | 83.9 ± 3.7 |

| 10% (v/v) | 64.7 ± 4.7 | |

| 30% (v/v) | 23.6 ± 0.8 | |

| Ethanol | 5% (v/v) | 77.3 ± 4.7 |

| 10% (v/v) | 71.3 ± 4.9 | |

| 30% (v/v) | 26.7 ± 0.9 | |

| DMSO | 5% (v/v) | 51.1 ± 0.9 |

| 10% (v/v) | 69.8 ± 2.6 | |

| 30% (v/v) | 22.5 ± 3.0 |

| Item | Time (h) | B. bifidum | p Value | L. brevis | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | XOS | Control | XOS | ||||

| OD600 | 24 | 1.43 ± 0.22 | 1.84 ± 0.07 a | 0.012 | 0.84 ± 0.42 b | 1.87 ± 0.22 b | <0.01 |

| 48 | 0.93 ± 0.29 | 1.57 ± 0.19 b | 0.010 | 1.38 ± 0.52 ab | 2.31 ± 0.09 a | 0.037 | |

| 72 | 0.94 ± 0.60 | 1.30 ± 0.09 c | 0.277 | 2.00 ± 0.14 a | 2.43 ± 0.11 a | <0.01 | |

| pH | 24 | 6.88 ± 0.04 | 6.84 ± 0.04 | 0.193 | 6.93 ± 0.06 c | 6.86 ± 0.17 c | 0.494 |

| 48 | 6.99 ± 0.06 | 6.81 ± 0.16 | 0.083 | 7.39 ± 0.20 b | 7.30 ± 0.24 b | 0.572 | |

| 72 | 7.02 ± 0.13 | 6.74 ± 0.09 | 0.012 | 7.68 ± 0.20 a | 7.72 ± 0.11 a | 0.772 | |

| Xylanase (U/L) | 24 | 82.16 ± 2.99 | 222.56 ± 9.51 a | <0.01 | 84.41 ± 5.31 | 171.44 ± 16.40 a | <0.01 |

| 48 | 76.97 ± 7.88 | 213.31 ± 16.80 a | <0.01 | 89.11 ± 11.78 | 156.75 ± 15.26 ab | <0.01 | |

| 72 | 79.94 ± 8.66 | 150.53 ± 9.38 b | <0.01 | 110.63 ± 17.21 | 135.92 ± 9.51 b | 0.090 | |

| β-glucosidase (U/L) | 24 | 47.66 ± 2.66 b | 85.72 ± 2.14 | <0.01 | 34.13 ± 0.93 c | 81.79 ± 17.72 | 0.012 |

| 48 | 62.31 ± 8.16 a | 91.61 ± 5.11 | <0.01 | 37.01 ± 1.19 b | 92.80 ± 19.79 | <0.01 | |

| 72 | 49.90 ± 1.57 b | 91.19 ± 6.55 | <0.01 | 44.02 ± 3.05 a | 86.77 ± 6.78 | <0.01 | |

| β-galactosidase (U/L) | 24 | 39.32 ± 0.70 b | 173.47 ± 5.08 | <0.01 | 31.19 ± 2.94 | 219.17 ± 9.78 b | <0.01 |

| 48 | 41.70 ± 2.26 ab | 147.82 ± 30.92 | <0.01 | 42.75 ± 13.24 | 229.61 ± 12.38 ab | <0.01 | |

| 72 | 43.88 ± 2.27 a | 151.88 ± 33.88 | <0.01 | 42.05 ± 7.21 | 246.01 ± 12.11 a | <0.01 | |

| α-galactosidase (U/L) | 24 | 40.93 ± 1.82 | 74.01 ± 1.35 b | <0.01 | 33.85 ± 1.28 | 75.56 ± 4.30 b | <0.01 |

| 48 | 42.82 ± 2.94 | 78.08 ± 4.45 ab | <0.01 | 35.32 ± 1.87 | 147.82 ± 5.61 a | <0.01 | |

| 72 | 42.75 ± 1.13 | 82.70 ± 3.92 a | <0.01 | 43.88 ± 9.86 | 90.38 ± 7.96 c | <0.01 | |

| β-xylosidase (U/L) | 24 | 9.53 ± 1.19 | 41.63 ± 1.16 b | <0.01 | ND b | 50.74 ± 8.00 b | <0.01 |

| 48 | 12.06 ± 2.42 | 54.67 ± 11.73 b | <0.01 | ND b | 147.40 ± 14.93 a | <0.01 | |

| 72 | 12.48 ± 1.42 | 92.10 ± 22.62 a | <0.01 | 4.14 ± 0.95 a | 135.55 ± 10.14 a | <0.01 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Qiu, Q.; Zhao, X. Xylo-Oligosaccharide Production from Wheat Straw Xylan Catalyzed by a Thermotolerant Xylanase from Rumen Metagenome and Assessment of Their Probiotic Properties. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112602

Wu Y, Liu C, Qiu Q, Zhao X. Xylo-Oligosaccharide Production from Wheat Straw Xylan Catalyzed by a Thermotolerant Xylanase from Rumen Metagenome and Assessment of Their Probiotic Properties. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112602

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yajing, Chanjuan Liu, Qinghua Qiu, and Xianghui Zhao. 2025. "Xylo-Oligosaccharide Production from Wheat Straw Xylan Catalyzed by a Thermotolerant Xylanase from Rumen Metagenome and Assessment of Their Probiotic Properties" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112602

APA StyleWu, Y., Liu, C., Qiu, Q., & Zhao, X. (2025). Xylo-Oligosaccharide Production from Wheat Straw Xylan Catalyzed by a Thermotolerant Xylanase from Rumen Metagenome and Assessment of Their Probiotic Properties. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112602