Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors in Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus suis Serotype 2 Isolates Using Whole-Genome Sequencing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of SS2

2.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Library Construction

2.3. Genome Functional Elements Analysis

2.4. Genome Subsystem Analysis

2.5. Genome Functional Annotation Analysis

2.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assessment

2.7. Animals

2.8. Animal Infection Experiments

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

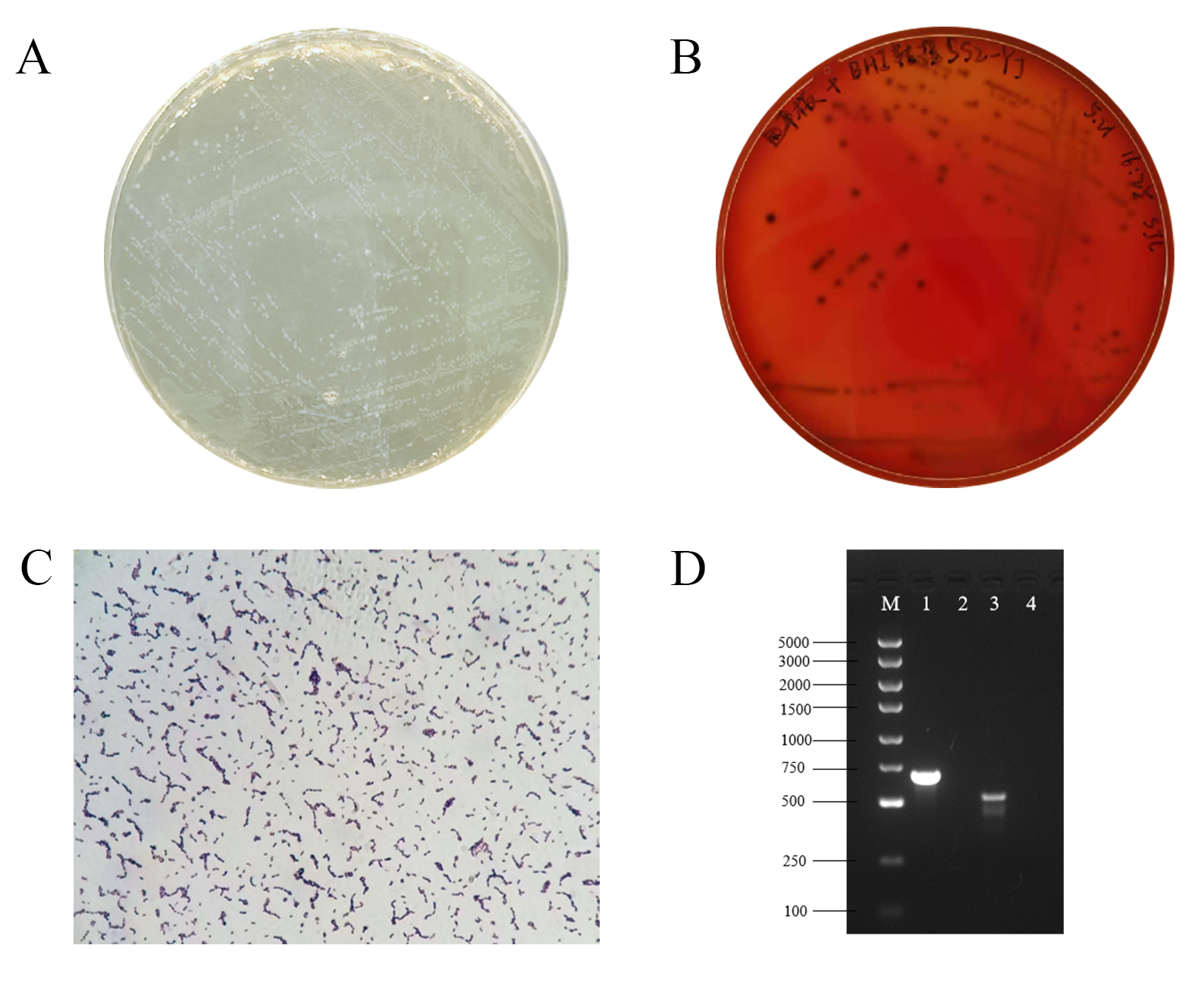

3.1. Identification of SS2

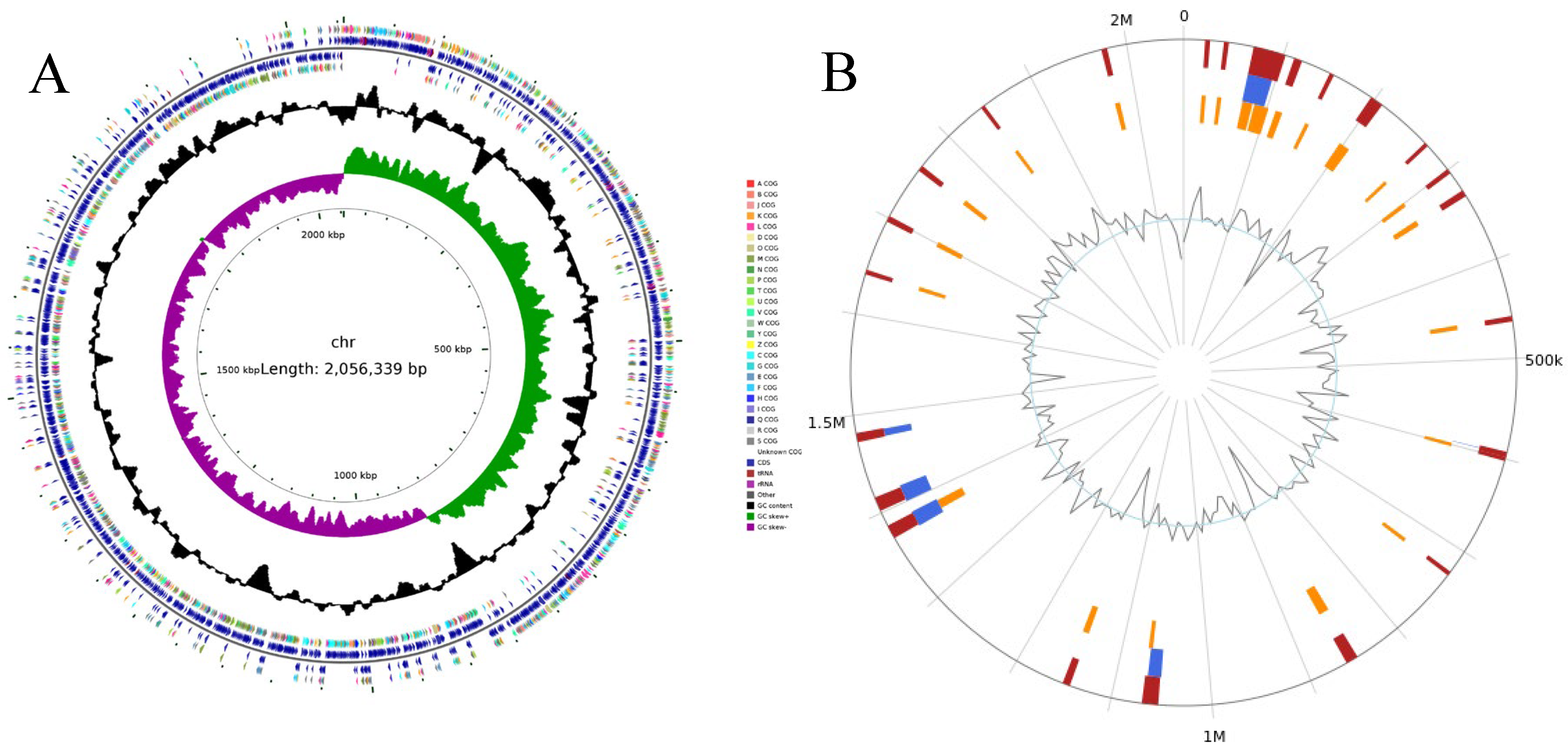

3.2. Quality Assessment of Genome Assemblies

3.3. Genome Functional Elements Analysis Results

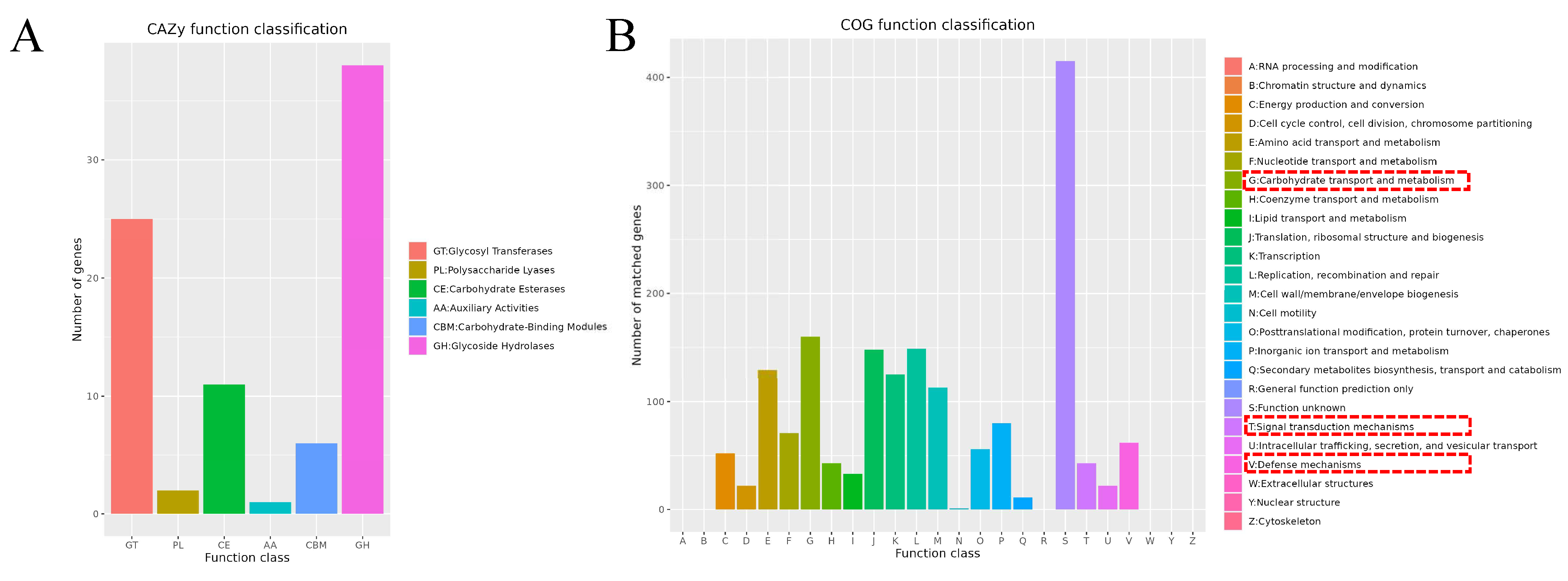

3.4. Genome Subsystem Analysis Results

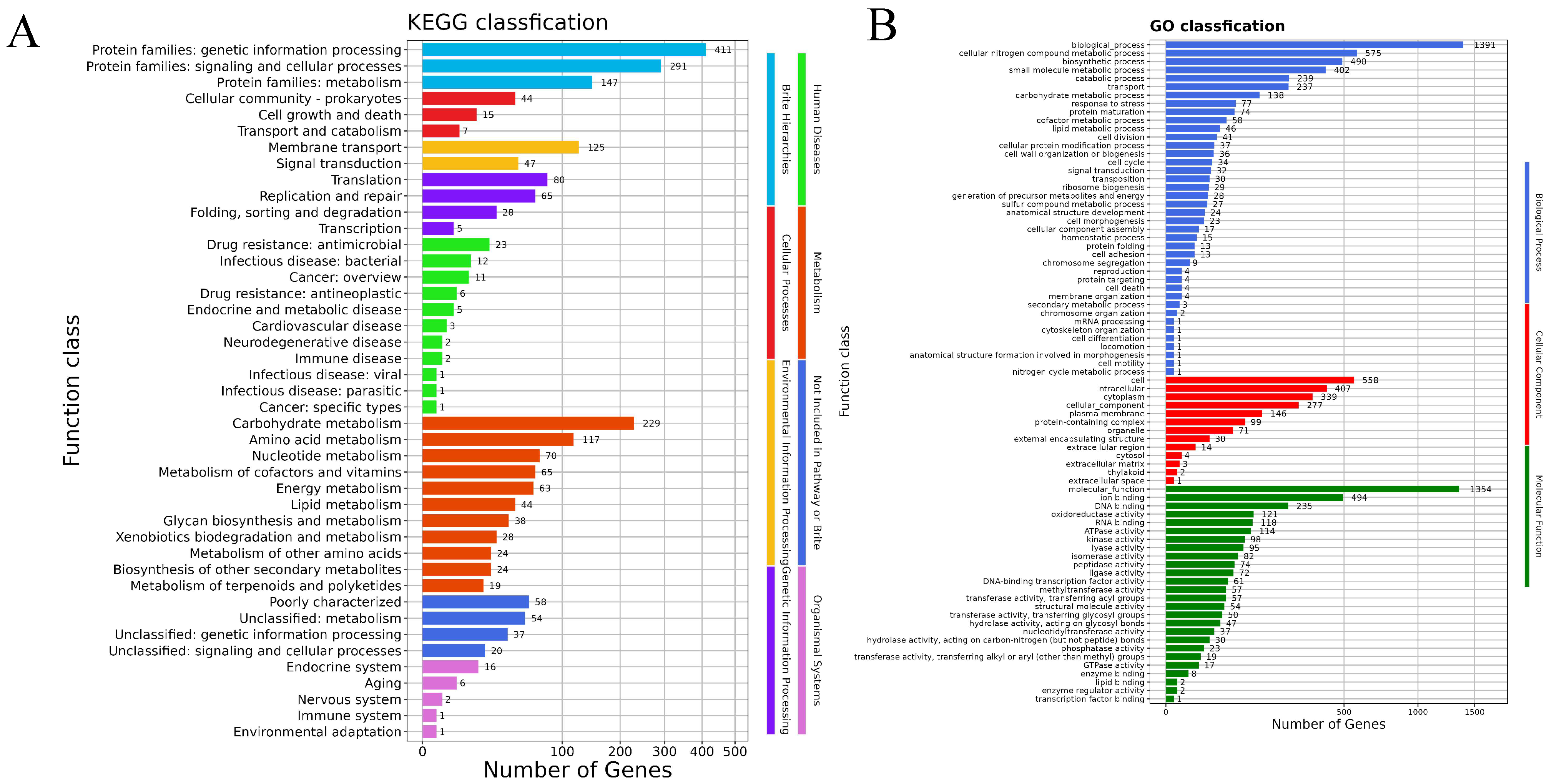

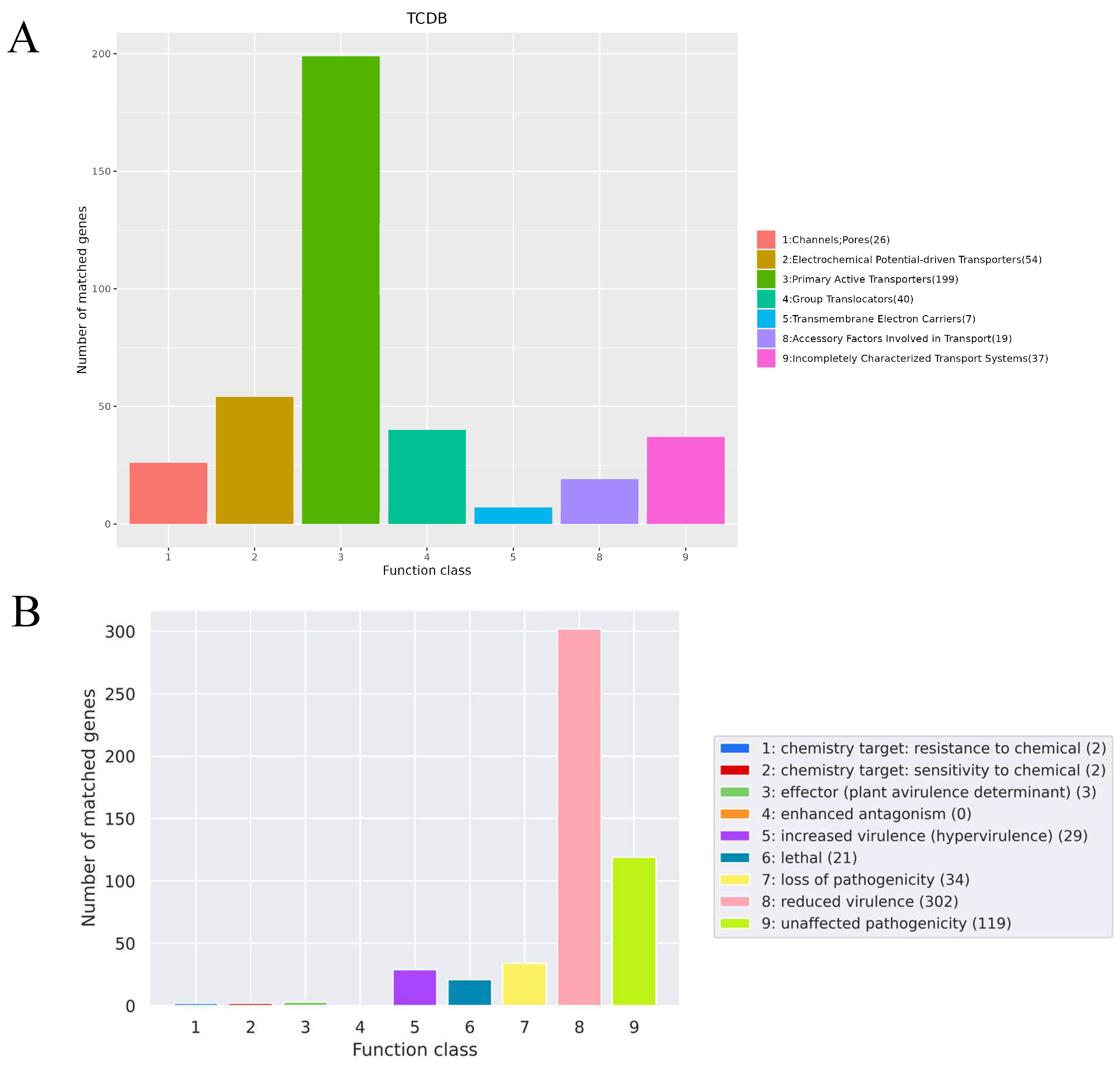

3.5. Genome Functional Annotation Analysis Results

3.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Analysis

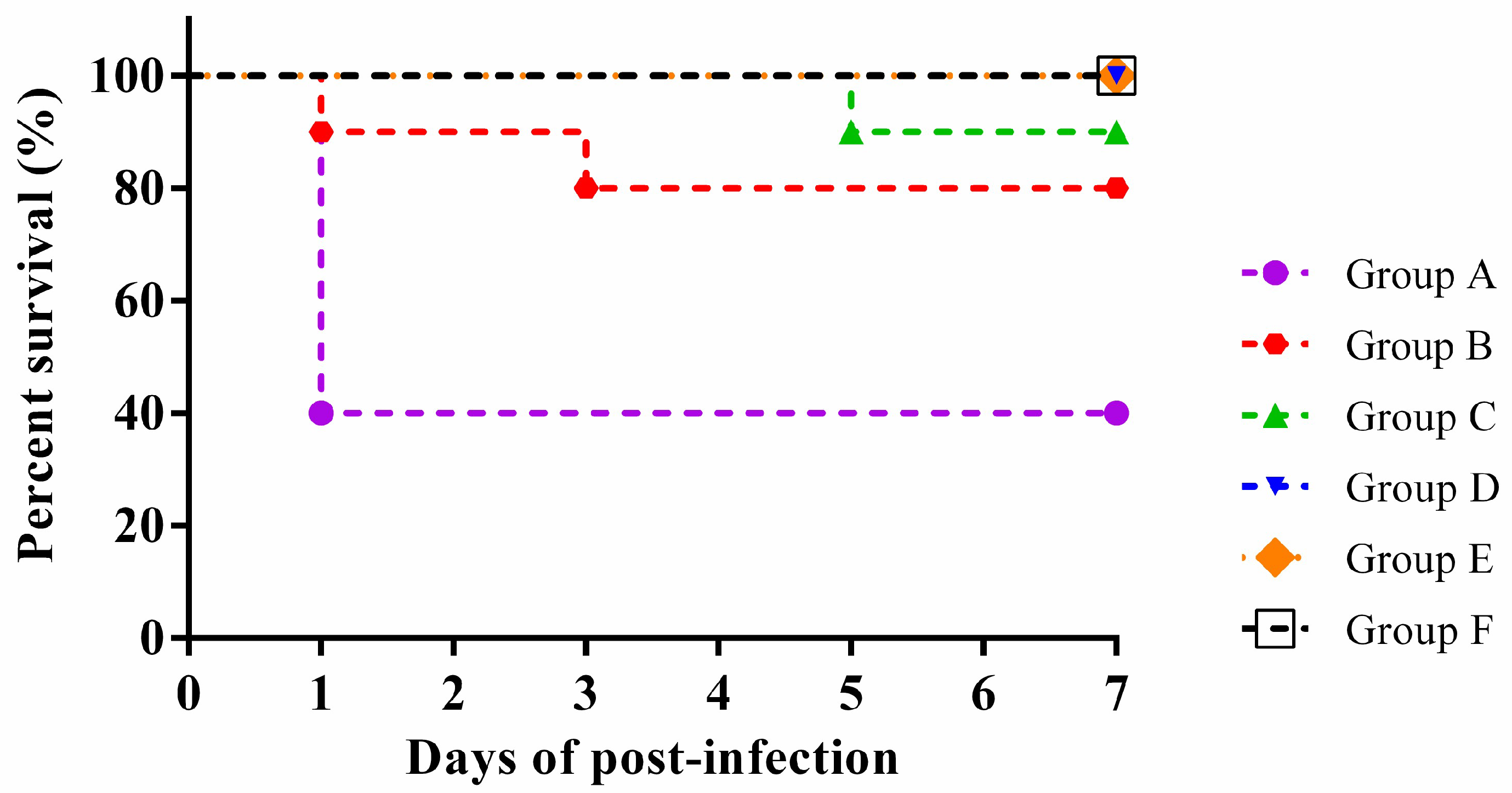

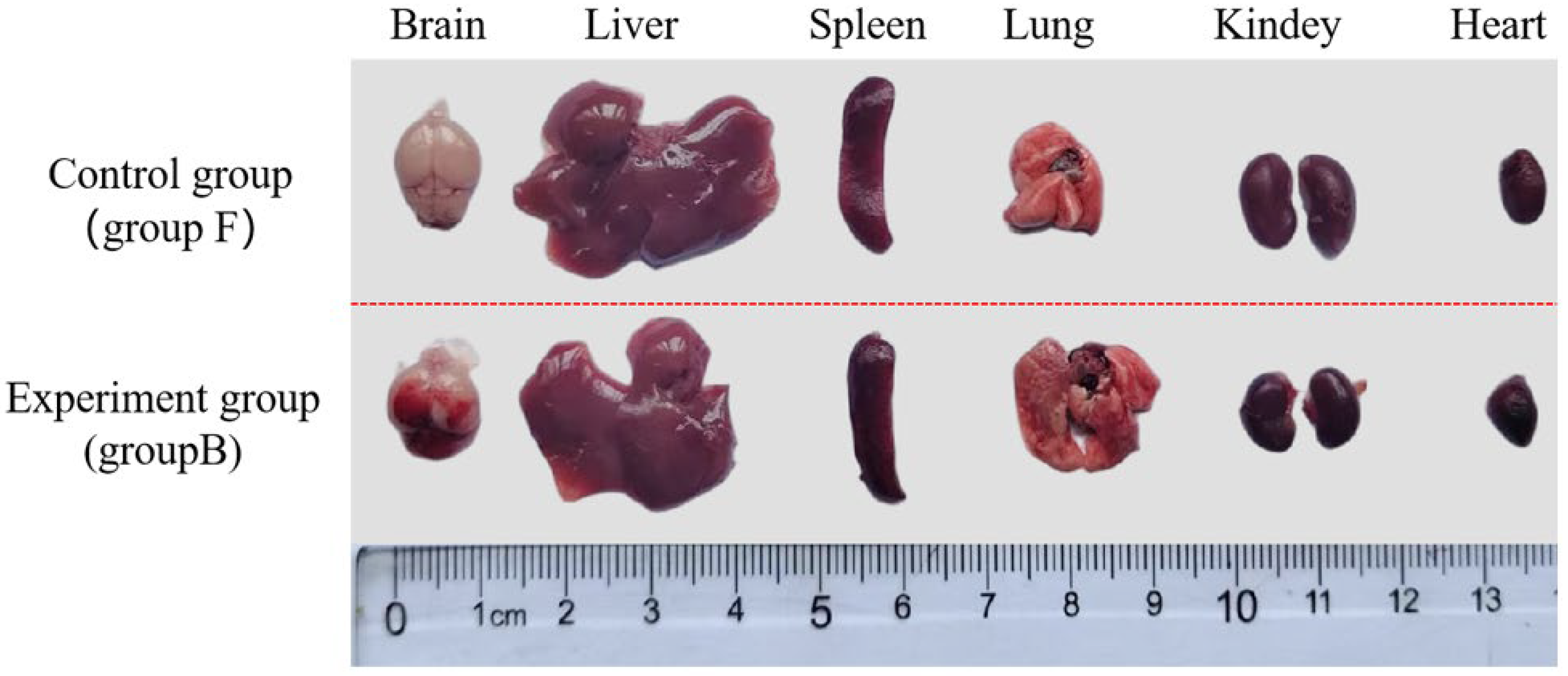

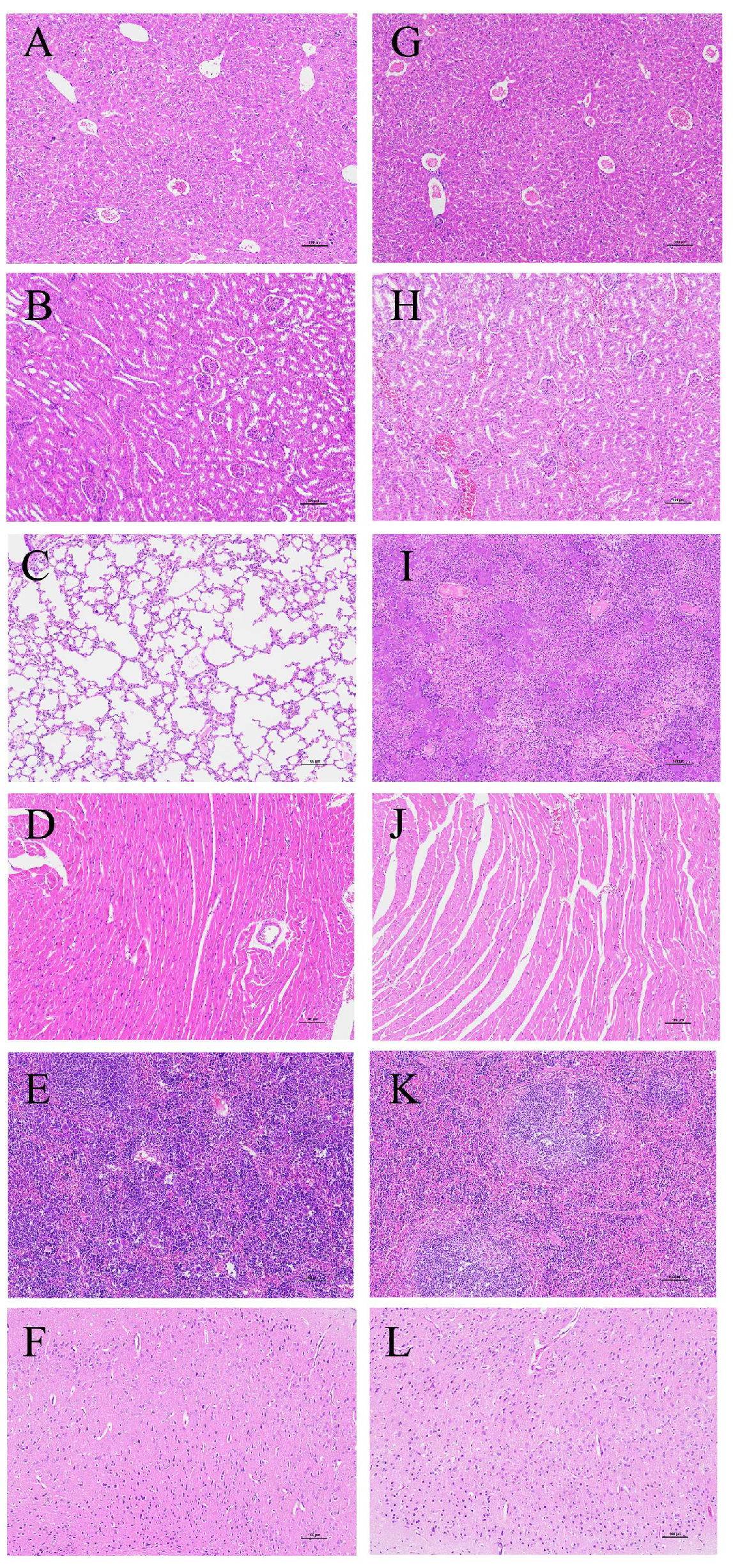

3.7. Animal Infection Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| S. Suis | Streptococcus suis |

| SS2 | Streptococcus suis serotype 2 |

| TSS | Streptococcus suis toxic shock syndrome |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

| PDR | Pan-drug-resistant |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| ncRNA | Non-coding RNA |

| rRNA | Ribosome RNA |

| sRNA | Small RNA |

| tRNA | Transfer RNA |

| snRNA | Small nuclear RNA |

| snoRNA | Small nucleolar RNA |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| NR | Non-Redundant Protein Database |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| COG | Clusters of Orthologous Groups |

| TCDB | Transporter Classification Database |

| CAZy | Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database |

| PHI | Pathogen–Host Interactions Database |

References

- Tan, C.; Zhang, A.; Chen, H.; Zhou, R. Recent proceedings on prevalence and pathogenesis of Streptococcus suis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2019, 32, 473–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, M. Streptococcus suis research: Progress and challenges. Pathogens 2020, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Gao, G. Uncovering newly emerging variants of Streptococcus suis, an important zoonotic agent. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Wang, M.; Yi, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Gottschalke, M.; Zheng, H.; et al. Investigation of genomic and pathogenicity characteristics of Streptococcus suis ST1 human strains from Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GX) between 2005 and 2020 in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2339946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Zhu, X.; Jing, H.; Du, H.; Segura, M.; Zheng, H.; Kan, B.; Wang, L.; Bai, X.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Streptococcus suis sequence type 7 outbreak, Sichuan, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, M.; Segura, M. The pathogenesis of the meningitis caused by Streptococcus suis: The unresolved questions. Vet. Microbiol. 2000, 76, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fittipaldi, N.; Segura, M.; Grenier, D.; Gottschalk, M. Virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of the infection caused by the swine pathogen and zoonotic agent Streptococcus suis. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura, M.; Aragon, V.; Brockmeier, S.L.; Gebhart, C.; Greeff, A.; Kerdsin, A.; O’Dea, M.A.; Okura, M.; Saléry, M.; Schultsz, C.; et al. Update on Streptococcus suis research and prevention in the Era of antimicrobial restriction: 4th International Workshop on S. suis. Pathogens 2020, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Wang, C.; Feng, Y.; Yang, W.; Song, H.; Chen, Z.; Yu, H.; Pan, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome caused by Streptococcus suis serotype 2. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneerat, K.; Yongkiettrakul, S.; Kramomtong, I.; Tongtawe, P.; Tapchaisri, P.; Luangsuk, P.; Chaicumpa, W.; Gottschalk, M.; Srimanote, P. Virulence genes and genetic diversity of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 isolates from Thailand. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2013, 60, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitlaru, T.; Israeli, M.; Rotem, S.; Elia, U.; Bar-Haim, E.; Ehrlich, S.; Cohen, O.; Shafferman, A. A novel live attenuated anthrax spore vaccine based on an acapsular Bacillus anthracis Sterne strain with mutations in the htrA, lef and cya genes. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6030–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Jin, M.; Li, J.; Grenier, D.; Wang, Y. Antibiotic resistance related to biofilm formation in Streptococcus suis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8649–8660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, C.; Varaldo, P.E.; Facinelli, B. Streptococcus suis, an emerging drug-resistant animal and human pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifait, L.; Dominguez-Punaro, M.D.L.C.; Vaillancourt, K.; Bart, C.; Slater, J.; Frenette, M.; Gottschalk, M.; Grenier, D. The cell envelope subtilisin-like proteinase is a virulence determinant for Streptococcus suis. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedano, S.; Silva, B.B.I.; Sangalang, A.G.M.; Mendioro, M. Streptococcus suis and S. parasuis in the Philippines: Biochemical, molecular, and antimicrobial resistance characterization of the first isolates from local swine. Philipp. Sci. Lett. 2020, 13, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Bian, C.; Wang, J.; Liang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Yao, H.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Zheng, H.; et al. The population structure, antimi-crobial resistance, and pathogenicity of Streptococcus suis cps31. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 259, 109149–109156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Wang, M.; Gottschalk, M.; Vela, A.I.; Estrada, A.A.; Wang, J.; Du, P.; Luo, M.; Zheng, H.; Wu, Z. Genomic and pathogenic investigations of Streptococcus suis serotype 7 population derivedfrom a human patient and pigs. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 1960–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, S.; Biggel, M.; Schneeberger, M.; Cernela, N.; Rademacher, F.; Schmitt, S.; Stephan, R. Genetic diversity and antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus suis from diseased Swiss pigs collected between 2019–2022. Vet. Microbiol. 2024, 293, 110084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uruén, C.; Gimeno, J.; Sanz, M.; Fraile, L.; Marín, C.M.; Arenas, J. Invasive Streptococcus suis isolated in Spain contain a highly promiscuous and dynamic resistome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Schwarz, S.; Brenciani, A.; Li, C.; Du, X. Streptococcus suis Serotype 14: A Nonnegligible Zoonotic Population. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2025, 2025, 5779652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Lv, X.; Duan, D.; Wang, L.; Huang, J. Characterization of a Linezolid- and Vancomycin-Resistant Streptococcus suis Isolate That Harbors optrA and vanG Operons. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negare, R.; Suzana, K.S. Mechanisms of Action for Antimicrobial Peptides with Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Functions. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO/IEC 23418:2022; Microbiology of the Food Chain-Whole Genome Sequencing for Typing and Genomic Characterization of Bacteria-General Requirements and Guidance. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75509.html (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Anita, C.S.; van Schaik, W. Challenges and opportunities for whole-genome sequencing–based surveillance of antibiotic resistance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1388, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, S.; Cao, M.; Hu, D.; Wang, C. Streptococcus suis infection: An emerging/reemerging challenge of bacterial infectious diseases? Virulence 2014, 5, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlebowicz, M.; Jakubowski, P.; Smiatacz, T. Streptococcus suis Meningitis: Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation and Treatment. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019, 19, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DB34/T 2996-2017; Streptococcus Suis Inspection Operating Procedures. Anhui Provincial Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision: Hefei, China, 2017.

- Haas, B.; Grenier, D. Understanding the virulence of Streptococcus suis: A veterinary, medical, and economic challenge. Med. Mal. Infect. 2018, 48, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, S.; Chen, L.; Guo, L.; Sun, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Establishment and Application of Quantitative Real-time PCR Method to Detect Streptococcus suis Serotype 2. China Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 2016, 43, 3107–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, F.; Scott, W.; Charles, M.; Justin, M.; Marta, B.; Wayne, E.; Michael, M.; Medhat, M.; Phoebe, K.; Zachary, T.; et al. Performance assessment of DNA sequencing platforms in the ABRF Next-Generation Sequencing Study. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Aziz, R.K.; Edwards, R.A. PhiSpy: A novel algorithm for finding prophages in bacterial genomes that combines similarity-and composition-based strategies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. In CLSI Supplement M100, 32nd ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, S.; Underwood, W.; Anthony, R.; Cartner, S.; Corey, D.; Grandin, T.; Yanong, R.P. AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition; American Veterinary Medical Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- AS 5013.11.1:2018; Food Microbiology, Method 11.1: Microbiology of the Food Chain—Preparation of Test Samples, Initial Suspension and Decimal Dilutions for Microbiological Examination—General Rules for the Preparation of the Initial Suspension and Decimal Dilutions (ISO 6887-1:2017, MOD). Australian Standards: Sydney, Australia, 2018.

- Shang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, S.; Du, C.; Schwarz, S.; Li, C.; Du, X. A novel lysin Ply691 exhibits potent bactericidal activity against Streptococcus suis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1653748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, A.H.; Jacobson, K.A.; Rose, J.; Zeller, R. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. CSH Protoc. 2008, 2008, pdb-prot4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Pan, I.; Du, H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, L. Eric-Pcr Fingerprinting Based Community Dna Hybridization to Pinpoint Genome Specific Fragments as Molecular Markers to Identify and Track Populations Common to Healthy Human Guts. J. Microbiol. Methods 2004, 59, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kho, C.; Lau, M.; Chung, H.; Chew, I.; Gan, H. Whole-genome sequencing of Pseudomonas koreensis isolated from diseased Tor tambroides. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, J.; Feder, I.; Okwumabua, O.; Chengappa, M. Streptococcus suis: Past and present. Vet. Res. Commun. 1997, 21, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdsin, A.; Segura, M.; Fittipaldi, N.; Gottschalk, M. Sociocultural Factors Influencing Human Streptococcus suis Disease in Southeast Asia. Foods 2022, 11, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechêne-Tempier, M.; Marois-Créhan, C.; Libante, V.; Jouy, E.; Leblond-Bourget, N.; Payot, S. Update on the Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance and the Mobile Resistome in the Emerging Zoonotic Pathogen Streptococcus suis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwobodo, D.C.; Ugwu, M.C.; Anie, C.O.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S.; Ikem, J.C.; Chigozie, U.V.; Saki, M. Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongkiettrakul, S.; Maneerat, K.; Arechanajan, B.; Malila, Y.; Srimanote, P.; Gottschalk, M.; Visessanguan, W. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus suis isolated from diseased pigs, asymptomatic pigs, and human patients in Thailand. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, F.; Gaudreau, A.; Lubega, S.; Zaker, A.; Xia, X.; Mer, A.; D’ostaa, V.M. Characterization of the diversity of type IV secretion system-encoding plasmids in Acinetobacter. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2320929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brovedan, M.A.; Cameranesi, M.M.; Limansky, A.S.; Morán-Barrio, J.; Marchiaro, P.; Repizo, G.D. What do we know about plasmids carried by members of the Acinetobacter genus? World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, J.; Buffet, A.; Haudiquet, M.; Rocha, E.; Rendueles, O. Modular prophage interactions driven by capsule serotype select for capsule loss under phage predation. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2980–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, P.; Dong, F.; Chen, S.; Yao, H.; Pan, Z. Identification and genomics analysis of a clinical strain of Streptococcus suis serotype 1. Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 2021, 53, 73–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenheft, B.; Sternberg, S.H.; Doudna, J.A. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 2012, 482, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Li, B.; Bu, R.; Wang, Z.; Xin, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, W. A highly efficient method for genomic deletion across diverse lengths in thermophilic Parageobacillus thermoglucosidasius. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2024, 9, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, P.; Sun, C.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Preplanned Studies: Genomic Insight into the Antimicrobial Resistance of Streptococcus suis-Six Countries, 2011–2019. China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, T.; Hori, T.; Sugimori, G.; Yamano, Y. Pharmacodynamic assessment based on mutant prevention concentrations of fluoroquinolones to prevent the emergence of resistant mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3810–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafii, F.; Park, M.; Wynne, R. Evidence for active drug efflux in fluoroquinolone resistance in Clostridium hathewayi. Chemotherapy 2005, 51, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, S.; Erdeljan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Ding, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Yu, J.; et al. Streptococcus suis: Epidemiology and resistance evolution of an emerging zoonotic bacteria. One Health 2025, 21, 101098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Morales, L.; Pérez-Sancho, M.; García-Seco, T.; Balseiro, A.; Pérez-Domingo, A.; Buendía, A.; Diez-Guerrier, A.; García, M.; Mareque, P.; Risalde, M.; et al. Exploring trained immunity to complement vaccination against Streptococcus suis in swine. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2025, 172, 105498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecht, U.; Stockhofe-Zurwieden, N.; Tetenburg, B.J.; Wisselink, H.J.; Smith, H.E. Virulence of Streptococcus suis type 2 for mice and pigs appeared host-specific. Vet. Microbiol. 1997, 58, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, P.M.; Rolph, C.; Ward, P.N.; Bentley, R.W.; Leigh, J.A. Epithelial invasion and cell lysis by virulent strains of Streptococcus suis is enhanced by the presence of suilysin. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1999, 26, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecht, U.; Wisselink, H.J.; Jellema, M.L.; Smith, H.E. Identification of two proteins associated with virulence of Streptococcus suis type 2. Infect. Immun. 1991, 59, 3156–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Bao, Q.; Kou, Z.; Wang, Q. Case Report: One Human Streptococcus Suis Infection in Shandong Province, China. Medicine 2021, 102, e33491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lai, H.; Dong, W.; Tan, C. Advances in antivirulence natural products targeting the suilysin of Streptococcus suis. Anim. Dis. 2025, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biochemical Test | Results | Biochemical Test | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Peptone | − | L-Arabinose | − |

| Esculin | + | Mannite | + |

| 6.5% Salt Meat Broth | − | Melezitose | − |

| pH 9.6 Broth | − | D-ribose | − |

| Raffinose | + | Lnulin | + |

| Lactose | + | Glycerin | + |

| Sorbitol | − | Hippurate | − |

| Mannose | + |

| Genomic Parameter | Value for Parameter |

|---|---|

| Sequence length/bp | 2,056,339 |

| GC content/% | 41.30 |

| ORF number | 1973 |

| tRNA copy number | 56 |

| rRNA copy number | 12 |

| ncRNA copy number | 34 |

| CRISPRs number | 2 |

| Prophage number | 4 |

| Short interspersed repeats number | 6 |

| Long interspersed repeats number | 35 |

| Long terminal repeats number | 111 |

| Transposons number | 52 |

| Unclassified interspersed repeats number | 5 |

| Satellites RNA number | 6 |

| Simple-repeats number | 0 |

| ORF Name | Gene Name (Abbreviations) | Function | Gene Size/bp | Description | VFs_ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr_138 | groEL (Growth essential, Large subunit) | Adherence | 1623 | Chaperonin GroEL | VFG012095(gb|WP_003435012) |

| chr_480 | tufA (Translation elongation Factor Tu, A copy) | 1197 | Elongation factor Tu | VFG046465(gb|WP_003028672) | |

| chr_1271 | fbp54 (Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, 54 kDa) | 1659 | Fibronectin-bing protein Fbp54 | VFG000959(gb|WP_010922232) | |

| chr_1890 | srtC4 (Sortase Class 4) | 807 | Class C sortase | VFG005293(gb|WP_000508992) | |

| chr_529 | neuB (N-acetyleuraminate biosynthesis synthase) | Immune modulation | 1017 | N-acetylneuraminate synthase | VFG005894(gb|WP_000262522) |

| chr_553 | cpsI (Capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene I) | 1113 | UDP-galactopyranose mutase | VFG002182(gb|WP_002376666) | |

| chr_1098 | wbtL (Wzy-biosynthesis of Transferase L) | 870 | Glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase | VFG047039(gb|WP_003018140) | |

| chr_1553 | gndA (6-phosphoGluconate Dehydrogenase, A chain) | 1428 | NADP-dependent phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | VFG048830(gb|WP_014907233) | |

| chr_1839 | hasC (Hyaluronic acid synthesis gene C) | 900 | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase HasC | VFG000964(gb|WP_010922799) | |

| chr_1379 | clpP (Caseinolytic protease Proteolytic subunit) | Stress survival | 591 | ATP-dependent Clp protease proteolytic subunit | VFG000077(gb|NP_465991) |

| ORF Name | Gene Name (Abbreviations) | Gene Size/bp | Description | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr_358 | tetM (Tetracycline resistance M) | 1920 | Tetracycline resistance ribosomal protection protein Tet(M) | 90.61 |

| chr_703 | parC (Paralyzed Cell division, C subunit) | 2418 | DNA topoisomerase IV subunit A | 81.61 |

| chr_139 | StrA (Streptomycin Adenylyltransferase) | 414 | 30S ribosomal protein S12 | 70.80 |

| chr_957 | folP (Dihydropteroate synthase) | 813 | Dihyropteroate synthase | 70.63 |

| chr_480 | tufA (Elongation Factor Thermo Unstable, A copy) | 1197 | Elongation factor Tu | 70.57 |

| chr_697 | grlB (GadRegulator locus B) | 1944 | DNA topoisomerase IV subunit B | 70.22 |

| chr_113 | rpoB (RNA polymerase Beta subunit) | 3573 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | 69.03 |

| chr_114 | rpoC (RNA polymerase Beta-prime subunit) | 3621 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | 68.78 |

| chr_1835 | imrD (Inner membrane Resistance protein D) | 1785 | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | 66.67 |

| chr_1288 | gyrB (DNA Gyrase Subunit B) | 1953 | DNA topoisomerase (ATP-hydrolyzing) subunit B | 65.15 |

| Antibiotics Classes | Antimicrobial Drugs | Inhibition Zone Diameter/mm | Susceptibility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactams | Third-generation cephalosporins | Cefoperazone | 23.07 ± 1.80 | S |

| Ceftriaxone | 25.00 ± 1.39 | S | ||

| Ceftazidime | 22.30 ± 0.70 | S | ||

| Penicillins | Ampicillin | 28.17 ± 0.57 | S | |

| Oxacillin | 14.00 ± 0.00 | I | ||

| Penicillin G | 25.23 ± 0.32 | I | ||

| Piperacillin | 29.87 ± 0.71 | S | ||

| First-generation cephalosporins | Cephradine | 25.33 ± 0.35 | S | |

| Cefazolin | 27.60 ± 0.66 | S | ||

| Cefalexin | 22.20 ± 0.26 | S | ||

| Aminoglycosides | Neomycin | 9.67 ± 0.35 | R | |

| Kanamycin | 10.77 ± 0.59 | R | ||

| Gentamicin | 9.83 ± 0.86 | R | ||

| Amikacin | 9.00 ± 0.00 | R | ||

| Tetracyclines | Minocycline | 12.83 ± 0.29 | R | |

| Doxycycline | 14.00 ± 0.50 | I | ||

| Tetracycline | 7.63 ± 0.35 | R | ||

| Fluoroquinolones | Ofloxacin | 19.83 ± 0.97 | S | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 20.03 ± 0.95 | S | ||

| Norfloxacin | 14.00 ± 0.30 | I | ||

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | 25.50 ± 0.46 | S | |

| Midecamycin | 21.53 ± 0.50 | S | ||

| Lincosamides | Clindamycin | 19.60 ± 0.53 | S | |

| Amphenicols | Chloramphenicol | 20.87 ± 0.81 | S | |

| Glycopeptides | Vancomycin | 18.17 ± 0.81 | S | |

| Sulfonamides | Cotrimoxazole | 22.10 ± 0.17 | S | |

| Polypeptide | Polymyxin B | 0.00 ± 0.00 | R | |

| Nitrofurans | Furazolidone | 0.00 ± 0.00 | R | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Sheng, J.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, W.; Liu, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X. Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors in Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus suis Serotype 2 Isolates Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112552

Zhang L, Wang M, Sheng J, Yu L, Zhao Y, Liao W, Liu Z, Yu J, Zhang X. Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors in Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus suis Serotype 2 Isolates Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112552

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lingling, Minglu Wang, Jiale Sheng, Lumin Yu, Yike Zhao, Wei Liao, Zitong Liu, Jiang Yu, and Xinglin Zhang. 2025. "Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors in Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus suis Serotype 2 Isolates Using Whole-Genome Sequencing" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112552

APA StyleZhang, L., Wang, M., Sheng, J., Yu, L., Zhao, Y., Liao, W., Liu, Z., Yu, J., & Zhang, X. (2025). Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors in Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus suis Serotype 2 Isolates Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112552