Heavy Metal and Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants Promote Resistance and Biofilm Formation in Vibrio Species from Shellfish

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Shellfish Samples

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Vibrio

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Resistance Gene Detection of Vibrio

2.4. Biofilm Formation Assay

2.5. Detection of Heavy Metals (Cadmium and Copper) and Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Mollusks

2.5.1. Determination of Copper

- (1)

- Calibration: Standard curves were constructed using copper solutions.

- (2)

- Sample preparation: Approximately 0.2 g of dried tissue was digested and diluted to a fixed volume.

- (3)

- Calculation: Copper content (10−6, dry weight) was calculated as follows:

2.5.2. Determination of Cadmium

- (1)

- Calibration: Standard curves were constructed using cadmium solutions.

- (2)

- Sample preparation: Approximately 2 g of dried tissue was digested and diluted to 25 mL.

- (3)

- Calculation: Cadmium content (10−6, dry weight) was calculated as follows:

2.5.3. Determination of Petroleum Hydrocarbons

- (1)

- Calibration: Standard curves were constructed using petroleum hydrocarbon solutions.

- (2)

- Sample preparation: Two to five grams of tissue were saponified, extracted, and diluted.

- (3)

- Calculation: Hydrocarbon content (10−6, dry weight) was calculated as follows:

2.6. Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Shellfish

2.6.1. Estimated Daily Intake of Heavy Metals

2.6.2. Health Risk Assessment

2.6.3. Total Hazard Index (HI) Assessment

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

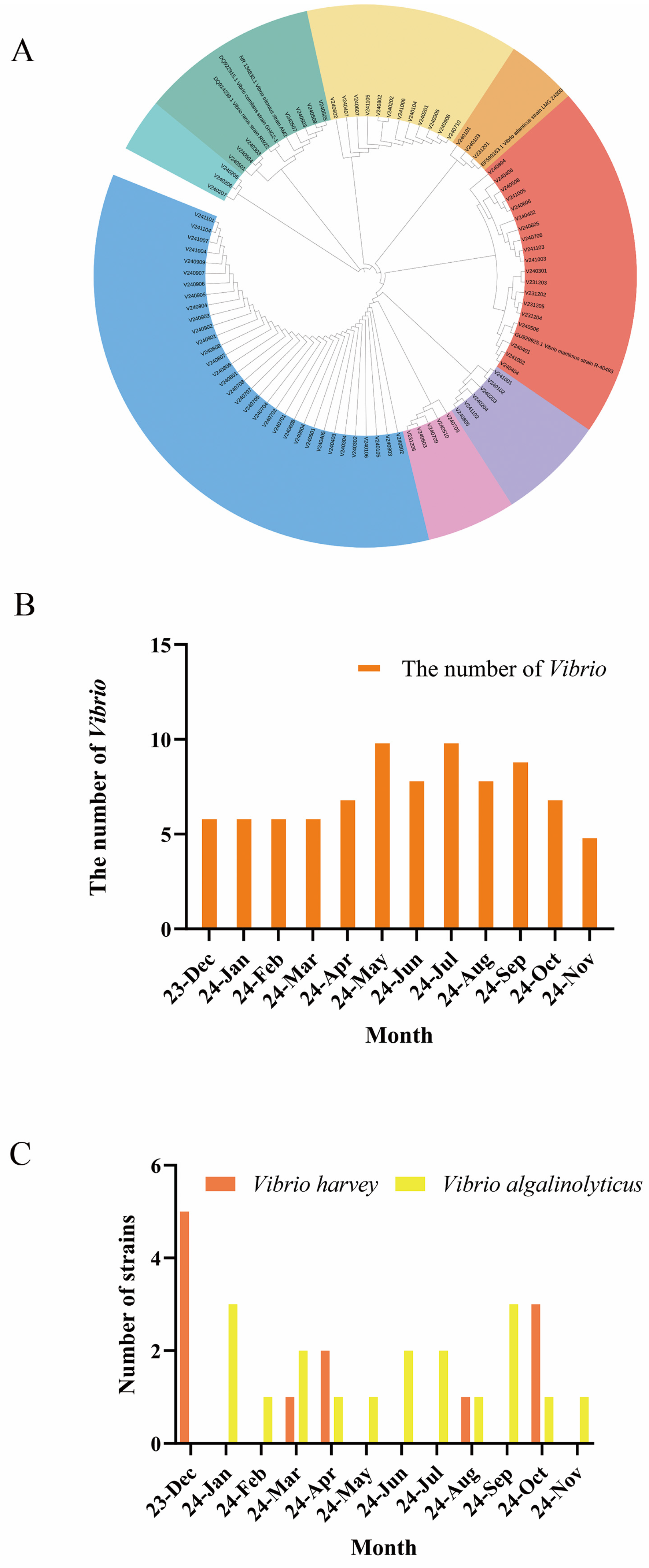

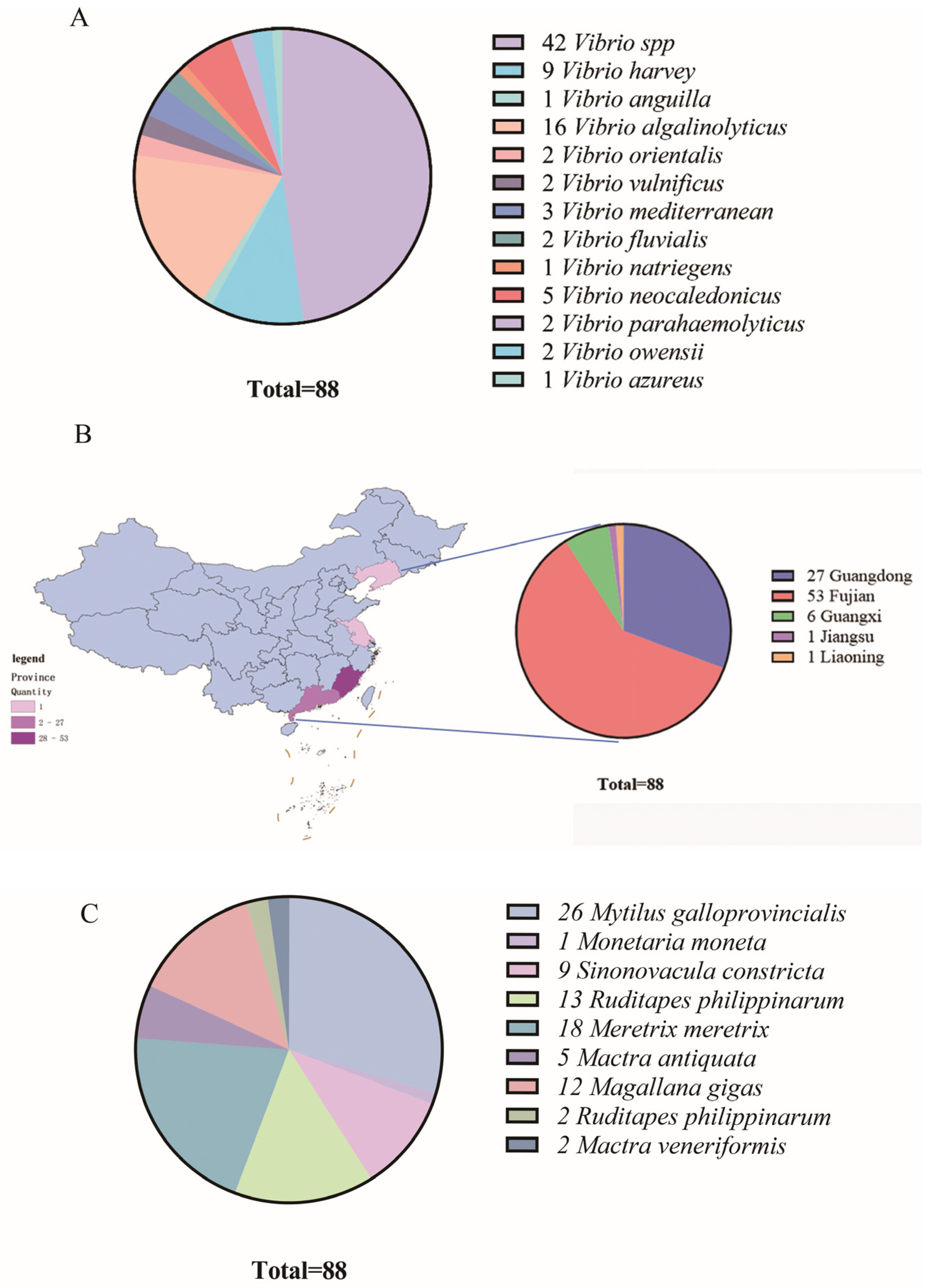

3.1. Abundance, Seasonal Variation, and Distribution of Vibrio Species

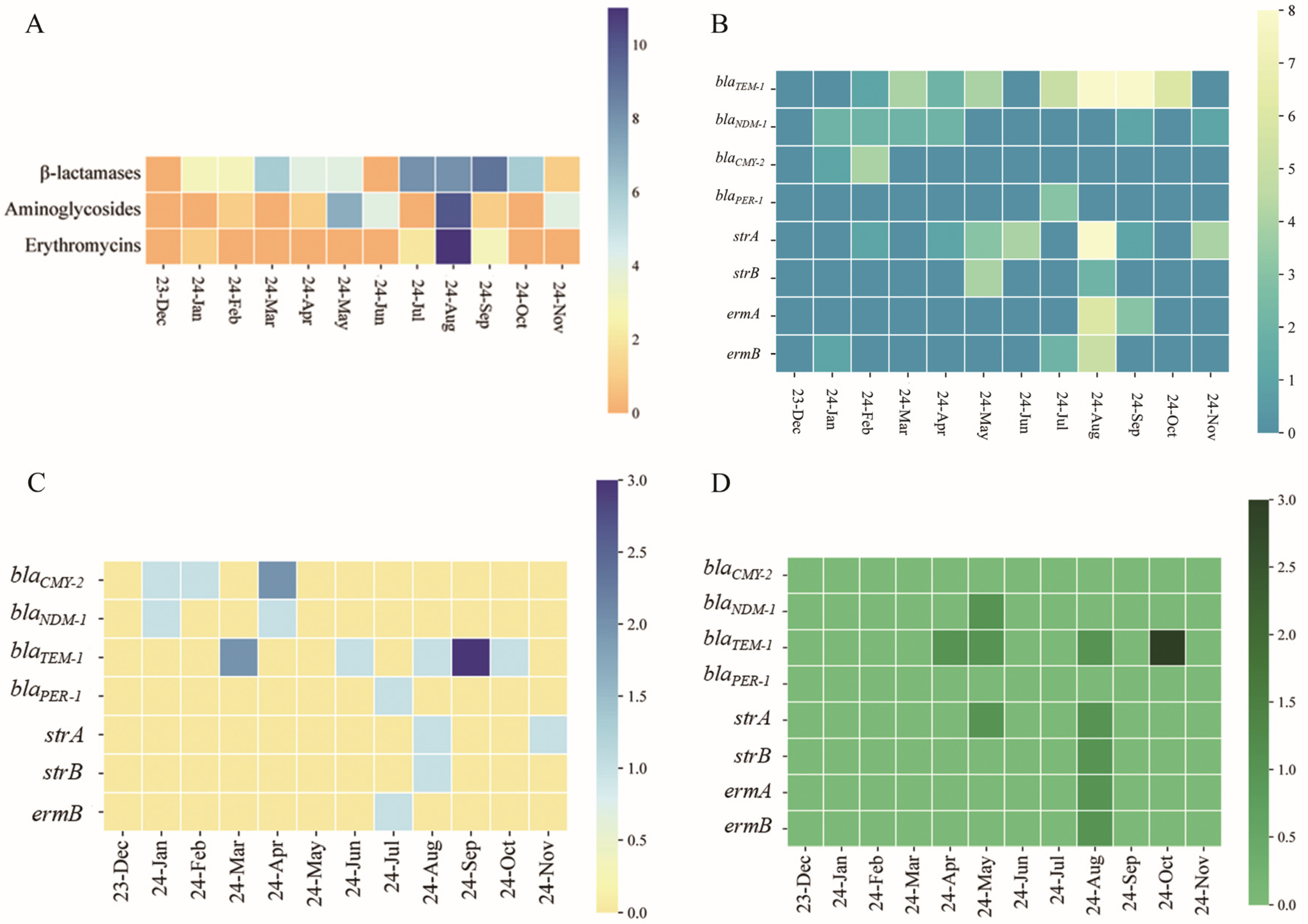

3.2. Antibiotic Resistance and Resistance Gene Detection in Shellfish-Derived Vibrio spp.

3.3. Biofilm Formation Capacity of Vibrio spp.

3.4. Cadmium, Copper, and Petroleum Hydrocarbon Content in Shellfish

3.5. Estimation of Daily Heavy Metal Intake

3.6. Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Shellfish

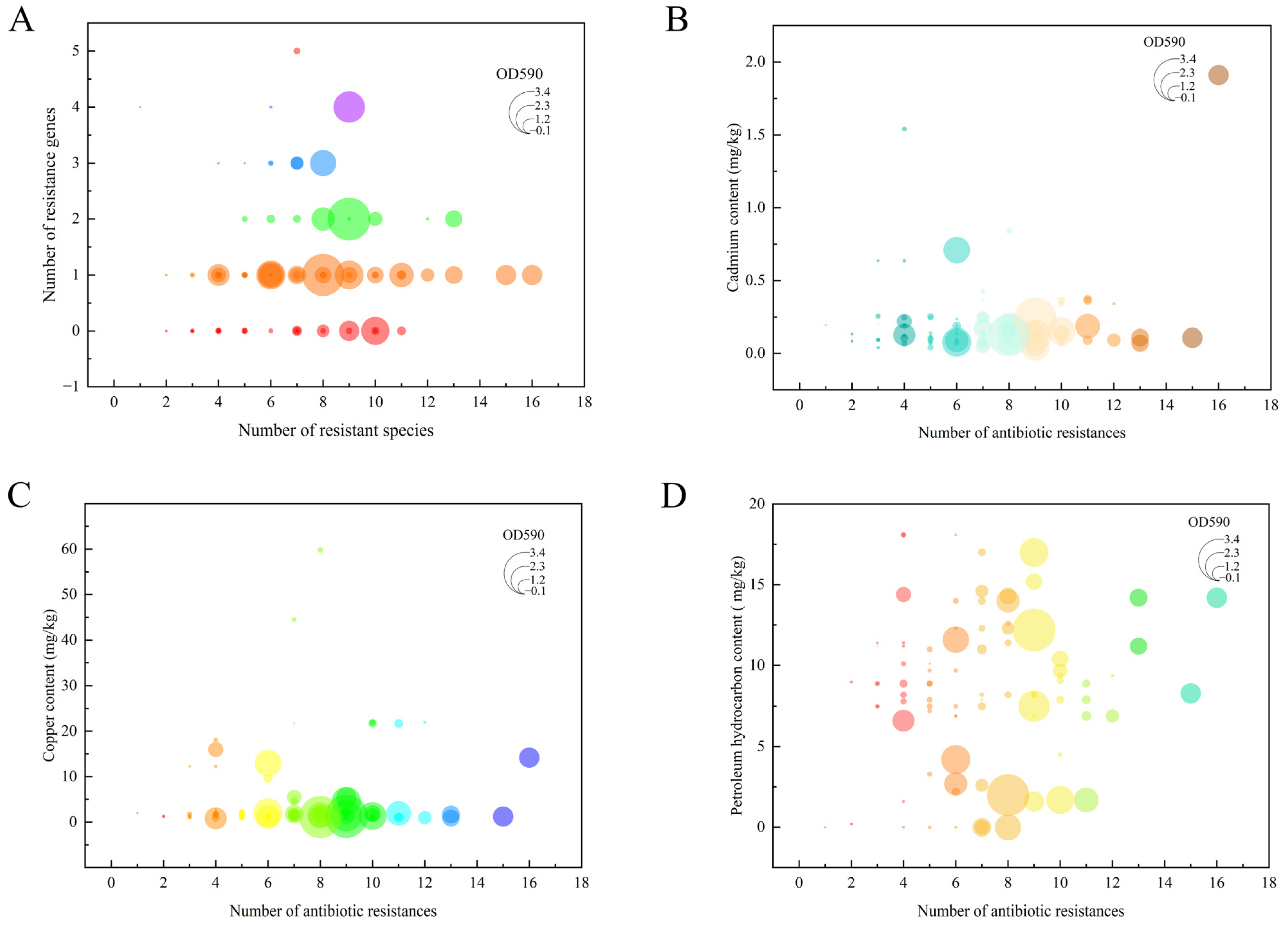

3.7. Correlation Analysis of Vibrio Antibiotic Resistance, Biofilm Formation, and Heavy Metal and Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contamination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parvin, N.; Joo, S.W.; Mandal, T.K. Nanomaterial-based strategies to combat antibiotic resistance: Mechanisms and applications. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lin, G.; Pengsakul, T.; Yan, Q.; Huang, L. Antibiotic resistance in Vibrio parahaemolyticus: Mechanisms, dissemination, and global public health challenges—A comprehensive review. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.I.G.; Silva, V.; de Sousa, T.; Calouro, R.; Saraiva, S.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Antimicrobial resistance in european companion animals practice: A One Health Approach. Animals 2025, 15, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okocha, R.C.; Olatoye, I.O.; Adedeji, O.B. Food safety impacts of antimicrobial use and their residues in aquaculture. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, G.; Le Vay, L.; Buck, B.H.; Costa-Pierce, B.A.; Dewhurst, T.; Heasman, K.G.; Nevejan, N.; Nielsen, P.; Nielsen, K.N.; Park, K.; et al. Prospects of low trophic marine aquaculture contributing to food security in a net zero-carbon world. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 875509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malham, S.K.; Rajko-Nenow, P.; Howlett, E.; Tuson, K.E.; Perkins, T.L.; Pallett, D.W.; Wang, H.; Jago, C.F.; Jones, D.L.; McDonald, J.E. The interaction of human microbial pathogens, particulate material and nutrients in estuarine environments and their impacts on recreational and shellfish waters. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2014, 16, 2145–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplitski, M.; Wright, A.C.; Lorca, G. Biological approaches for controlling shellfish-associated pathogens. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009, 20, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letchumanan, V.; Pusparajah, P.; Tan, L.T.H.; Yin, W.-F.; Lee, L.-H.; Chan, K.-G. Occurrence and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus from shellfish in Selangor, Malaysia. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, J.N.; Wegwu, M.O.; Uwakwe, A.A.; Osuoha, J.O. Analysis of total petroleum hydrocarbons, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and risk assessment of heavy metals in some selected finfishes at Forcados Terminal, Delta State, Nigeria. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2018, 9, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emenike, E.C.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Anidiobi, S.U. Heavy metal pollution in aquaculture: Sources, impacts and mitigation techniques. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 4476–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.S.; Park, S.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Oh, S.C.; Lim, E.S.; Hong, Y.-K.; Kim, M.-R. Pathogenic microorganisms, heavy metals, and antibiotic residues in seven Korean freshwater aquaculture species. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 25, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Xu, K.; Ke, A.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, R.; Xu, J. Pollution level and health risk assessment of the total petroleum hydrocarbon in marine environment and aquatic products: A case of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 86887–86897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare, A.; Eckert, E.; Corno, G. Co-selection of antibiotic and heavy metal resistance in freshwater bacteria. J. Limnol. 2016, 75, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.K.; Sodhi, K.K.; Shree, P.; Nitin, V. Heavy metals as catalysts in the evolution of antimicrobial resistance and the mechanisms underpinning co-selection. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiguchi, M.K. Temperature affects species distribution in symbiotic populations of Vibrio spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3550–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Guideline M100, 34th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Lin, D.; Chen, K.; Wong, M.H.Y.; Chen, S. First detection of AmpC β-lactamase blaCMY-2 on a conjugative IncA/C plasmid in a Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolate of food origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4106–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneha, K.G.; Anas, A.; Jayalakshmy, K.V.; Jasmin, C.; Das, P.V.; Pai, S.S.; Pappu, S.; Nair, M.; Muraleedharan, K.; Sudheesh, K.; et al. Distribution of multiple antibiotic resistant Vibrio spp across Palk Bay. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Mismatch between antimicrobial resistance phenotype and genotype of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from seafood. Food Control 2016, 59, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, N.; Asad, S.; Ahmed, T.; Setu, N.I.; Kayser, M.S.; Islam, M.S.; Islam, M.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Al Aman, D.A.; Rashid, R.B. In silico assessment of the genotypic distribution of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 7, 055–061. [Google Scholar]

- Xiu, L.; Li, Q.; Tian, Q.; Li, Y.; Pengsakul, T.; Lin, G.; Yan, Q.; Huang, L. sRNA-enriched outer membrane vesicles of Vibrio alginolyticus: Decisive architects of biofilm assembly. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 146102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Lu, S. Concentrations and health risk assessment of trace elements in animal-derived food in southern China. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Zhao, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhao, L.; Yin, Z. International comparison, forecast and promotion strategy of shellfish consumption in China. Aquac. Int. 2025, 33, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Ishak, N.S. Estimation of target hazard quotients and potential health risks for metals by consumption of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in Selangor, Malaysia. Sains Malays. 2017, 46, 1825–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S. Population health risk due to dietary intake of heavy metals in the industrial area of Huludao city, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 387, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böer, S.I.; Heinemeyer, E.A.; Luden, K.; Erler, R.; Gerdts, G.; Janssen, F.; Brennholt, N. Temporal and spatial distribution patterns of potentially pathogenic Vibrio spp. at recreational beaches of the German North Sea. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 65, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokashvili, T.; Whitehouse, C.A.; Tskhvediani, A.; Grim, C.J.; Elbakidze, T.; Mitaishvili, N.; Janelidze, N.; Jaiani, E.; Haley, B.J.; Lashkhi, N.; et al. Occurrence and diversity of clinically important Vibrio species in the aquatic environment of Georgia. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, O.E.; Osunla, A.C.; Okoh, A.I. Molecular detection and distribution of six medically important Vibrio spp. in selected freshwater and brackish water resources in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 617703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Qin, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.-H.; Li, T.-Y. Organic aquaculture in China: A review from a global perspective. Aquaculture 2013, 414, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Bai, L.; Yang, S.; Chu, C.; Yang, W.; Liu, Q. Identifying the high-risk areas and associated meteorological factors of dengue transmission in Guangdong Province, China from 2005 to 2011. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.N. Influence of environmental factors on Vibrio spp. in coastal ecosystems. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, J.S.; Egna, H.S.; Chopin, T.; Peterson, M.S.; Cao, L.; Pomeroy, R.; Verdegem, M.; Slack, W.T.; Bondad-Reantaso, M.G.; Cabello, F. Responsible aquaculture in 2050: Valuing local conditions and human innovations will be key to success. BioScience 2013, 63, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Lozano-Leon, A.; Varela-Pet, J.; Trinanes, J.; Pazos, Y.; Garcia-Martin, O. Environmental determinants of the occurrence and distribution of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the Rias of Galicia, Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schets, F.M.; van den Berg, H.H.J.L.; Rutjes, S.A.; Husman, A.M.D.R. Pathogenic Vibrio species in dutch shellfish destined for direct human consumption. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S.; Wickramanayake, M.V.K.S.; Dahanayake, P.S.; Heo, G.-J. Occurrence of virulence and extended-spectrum β-lactamase determinants in Vibrio spp. isolated from marketed hard-shelled mussel (Mytilus coruscus). Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.E.; Alessiani, A.; Donatiello, A.; Didonna, A.; D’attoli, L.; Faleo, S.; Occhiochiuso, G.; Carella, F.; Di Taranto, P.; Pace, L.; et al. Systematic survey of Vibrio spp. and Salmonella spp. in bivalve shellfish in Apulia region (Italy): Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberbeckmann, S.; Wichels, A.; Wiltshire, K.H.; Gerdts, G. Occurrence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio alginolyticus in the German Bight over a seasonal cycle. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2011, 100, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.H.; Shin, Y.J.; Jang, S.C.; Jung, Y.; So, J.-S. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio alginolyticus isolated from oyster in Korea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 21106–21112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Bates, A.H.; Jensen, H.M.; Mandrell, R. Norovirus binds to blood group A-like antigens in oyster gastrointestinal cells. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 43, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, F.; Wegner, K.M.; Polz, M.F. Oysters and vibrios as a model for disease dynamics in wild animals. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepi, M.; Focardi, S. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in aquaculture and climate change: A challenge for health in the Mediterranean area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, Z.F.; Islam, M.S.; Sabuj, A.A.M.; Pondit, A.; Sarkar, A.K.; Hossain, G.; Saha, S. Molecular detection and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Vibrio alginolyticus from shrimp (Penaeus monodon) and shrimp environments in Bangladesh. Aquac. Res. 2023, 2023, 5436552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Kaushik, A.; Kumar, D.; Bag, S. Foodborne pathogenic vibrios: Antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 638331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.B.; Shin, C.H.; Shin, Y.J.; Kim, P.H.; Park, J.I.; Kim, M.; Park, B.; So, J.-S. Heavy metal and antibiotic co-resistance in Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from shellfish. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yao, L.; Li, F.; Tan, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, L. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus from cultured sea cucumbers (Apostichopus japonicas). Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 59, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.H.; Shin, Y.J.; Yu, H.S.; Kim, S.; So, J.-S. Antibiotic and heavy-metal resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from oysters in Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 135, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T.T.T.; Hoang, T.T.H.; Fleischmann, S.; Pham, H.N.; Lai, T.L.H.; Cam, T.T.H.; Truong, L.O.; Le, V.P.; Alter, T. Quantification and antimicrobial resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in retail seafood in Hanoi, Vietnam. J. Food Prot. 2022, 85, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Li, X.Z. Antimicrobial resistance and drug efflux pumps in Vibrio and Legionella. In Efflux-Mediated Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria: Mechanisms, Regulation and Clinical Implications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 307–328. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.J.; Hsu, P.H.; Lin, H.T.V. A novel cooperative metallo-β-lactamase fold metallohydrolase from pathogen Vibrio vulnificus exhibits β-lactam antibiotic-degrading activities. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0032621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanthrao, R.; Chattopadhyay, I. Impact of environment on transmission of antibiotic-resistant superbugs in humans and strategies to lower dissemination of antibiotic resistance. Folia Microbiol. 2023, 68, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katonge, J.H.; Ally, Z.K. Evolutionary relationships and genetic diversity in the BlaTEM gene among selected gram-negative bacteria. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 42, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, A.K.; Hall, R.M. Transposon Tn 5393 e carrying the aphA1-containing transposon Tn 6023 upstream of strAB does not confer resistance to streptomycin. Microb. Drug Resist. 2011, 17, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Li, D.; Deng, X.; Xu, H.; Yu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H. The antimicrobial activity of cethromycin against Staphylococcus aureus and compared with erythromycin and telithromycin. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.M.; Lu, P.Z. Seasonal variations in antibiotic resistance genes in estuarine sediments and the driving mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 383, 121164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, X.; Niu, Z.; Lu, D.-P.; Zhao, S.; Sun, X.-L.; Wu, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-R.; Tou, F.-Y.; Hou, L.; et al. Seasonal and spatial distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in the sediments along the Yangtze Estuary, China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impey, R.E.; Hawkins, D.A.; Sutton, J.M.; Soares Da Costa, T.P. Overcoming intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms associated with the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetinkaya, Y.; Falk, P.; Mayhall, C.G. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Zuo, Y.; Li, Q.; Yan, Q.; Huang, L. Cooperative mechanisms of LexA and HtpG in the regulation of virulence gene expression in Pseudomonas plecoglossicida. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 8, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Trentin, D.; Giordani, R.B.; Macedo, A.J. Biofilmes bacterianos patogênicos: Aspectos gerais, importância clínica e estratégias de combate. Rev. Lib. 2013, 14, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, L.I.; Barbu, I.C.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Mobile genetic elements involved in the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. Rom. Arch. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 77, 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Valavanidis, A.; Vlahogianni, T.; Dassenakis, M.; Scoullos, M. Molecular biomarkers of oxidative stress in aquatic organisms in relation to toxic environmental pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2006, 64, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Jiang, L.; Shen, K.N.; Wu, C.; He, G.; Hsiao, C.-D. Transcriptome response to copper heavy metal stress in hard-shelled mussel (Mytilus coruscus). Genom. Data 2016, 7, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, F.; Lockington, R.; Mallavarapu, M.; Naidu, R. A comprehensive review of aliphatic hydrocarbon biodegradation by bacteria. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 176, 670–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Shen, X.; Jiang, M. Characteristics of total petroleum hydrocarbon contamination in sediments in the Yangtze Estuary and adjacent sea areas. Cont. Shelf Res. 2019, 175, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Jiang, W.; Pan, Y.; Li, F.; Tian, H. The occurrence and partition of total petroleum hydrocarbons in sediment, seawater, and biota of the eastern sea area of Shandong Peninsula, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 82186–82198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Huang, L. RNA biopesticides: A cutting-edge approach to combatting aquaculture diseases and ensuring food security. Mod. Agric. 2024, 2, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xiu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L. RNA-based biopesticides: Pioneering precision solutions for sustainable aquaculture in China. Anim. Res. One Health 2025, 3, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H. Potential risk assessment of heavy metals by consuming shellfish collected from Xiamen, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 2937–2947, Erratum in Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Li, R.; Gong, Y.; Shen, X.; Yu, L. Bioaccessibility-corrected health risk of heavy metal exposure via shellfish consumption in coastal region of China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet-Gougeon, A.; Bonnaure-Mallet, M. Biofilms as a mechanism of bacterial resistance. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2014, 11, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirghani, R.; Saba, T.; Khaliq, H.; Mitchell, J.; Do, L.; Chambi, L.; Diaz, K.; Kennedy, T.; Alkassab, K.; Huynh, T.; et al. Biofilms: Formation, drug resistance and alternatives to conventional approaches. AIMS Microbiol. 2022, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennequin, C.; Aumeran, C.; Robin, F.; Traore, O.; Forestier, C. Antibiotic resistance and plasmid transfer capacity in biofilm formed with a CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2123–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Xu, Z.; Fan, L. Response of heavy metal and antibiotic resistance genes and related microorganisms to different heavy metals in activated sludge. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 300, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Huang, L. Effect of the zinc transporter ZupT on the virulence mechanisms of mesophilic Aeromonas salmonicida SRW-OG1. Anim. Res. One Health 2023, 1, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallami, I.; Turki, Y.; Werheni Ammeri, R.; Khelifi, N.; Hassen, A. Effects of heavy metals on growth and biofilm-producing abilities of Salmonella enterica isolated from Tunisia. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete, F.; De La Fuente, L. Response of Xylella fastidiosa to zinc: Decreased culturability, increased exopolysaccharide production, and formation of resilient biofilms under flow conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, L.C.A.; de Oliveira, M.B.M. Effect of heavy metals on the biofilm formed by microorganisms from impacted aquatic environments. In Bacterial Biofilms; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.H.; Shin, Y.J.; Kim, W.R.; Kim, Y.; Song, K.; Oh, E.-G.; Kim, S.; Yu, H.; So, J.-S. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from oysters in Korea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Liao, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Co-spread of metal and antibiotic resistance within ST3-IncHI2 plasmids from E. coli isolates of food-producing animals. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnaji, N.D.; Anyanwu, C.U.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H. Mechanisms of heavy metal tolerance in bacteria: A review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elnabi, M.K.; Elkaliny, N.E.; Elyazied, M.M.; Azab, S.H.; Elkhalifa, S.A.; Elmasry, S.; Mouhamed, M.S.; Shalamesh, E.M.; Alhorieny, N.A.; Elaty, A.E.A.; et al. Toxicity of heavy metals and recent advances in their removal: A review. Toxics 2023, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibiotic | R | I | S |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 40 | 23 | 25 |

| PEN | 86 | 2 | 0 |

| AMK | 27 | 30 | 31 |

| CPZ | 30 | 35 | 23 |

| MI | 2 | 0 | 86 |

| TET | 4 | 0 | 84 |

| CXM | 24 | 23 | 41 |

| E | 18 | 63 | 7 |

| GEN | 23 | 39 | 26 |

| S | 40 | 36 | 12 |

| KAN | 26 | 44 | 18 |

| PB | 4 | 47 | 37 |

| VAN | 67 | 7 | 13 |

| DO | 6 | 1 | 81 |

| CTR | 13 | 4 | 71 |

| CZ | 30 | 15 | 43 |

| PIP | 48 | 19 | 21 |

| CAZ | 14 | 10 | 64 |

| AMP | 53 | 14 | 21 |

| EDI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metal | Minimum | Average | Maximum |

| Cadmium | 0.018 | 0.094 | 0.849 |

| Copper | 0.382 | 2.192 | 26.568 |

| THQi | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Average | Maximum | |

| Cadmium | 0.057 | 0.301 | 2.712 |

| Copper | 0.009 | 0.053 | 0.637 |

| HI | 0.066 | 0.354 | 3.349 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, G.; Li, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Pengsakul, T.; Chen, G.; Huang, L. Heavy Metal and Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants Promote Resistance and Biofilm Formation in Vibrio Species from Shellfish. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112522

Lin G, Li Y, Qiao Y, Pengsakul T, Chen G, Huang L. Heavy Metal and Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants Promote Resistance and Biofilm Formation in Vibrio Species from Shellfish. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112522

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Gongshi, Yingpeng Li, Ying Qiao, Theerakamol Pengsakul, Guobin Chen, and Lixing Huang. 2025. "Heavy Metal and Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants Promote Resistance and Biofilm Formation in Vibrio Species from Shellfish" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112522

APA StyleLin, G., Li, Y., Qiao, Y., Pengsakul, T., Chen, G., & Huang, L. (2025). Heavy Metal and Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants Promote Resistance and Biofilm Formation in Vibrio Species from Shellfish. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112522