Extracellular Vesicles from Streptococcus suis Promote Bacterial Pathogenicity by Disrupting Macrophage Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain and Culture Conditions

2.2. Isolation and Purification of EVs

2.3. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) to Measure Concentration and Particle Size of EVs

2.4. Determination of Protein Concentration in EVs

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Transmission Electron Microscopy Observations of EVs

2.6. Cell Cultivation

2.7. Cytotoxicity Was Assessed by Calcein-AM/PI Staining of Cells

2.8. Detection of EV Internalization by Flow Cytometry

2.9. Fluorescence Microscopy of EV Internalization in Mammals

2.10. Determination of the Effect of EVs on Cellular Activity

2.11. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase

2.12. Bacterial Adhesion and Invasion Assays

2.13. Different Treatments for EVs

2.14. Metabolomics Analysis Based on LC-MS/MS

2.15. Galleria mellonella (G. mellonella) Survival Experiments

2.16. Pathogenicity Experiment in Mouse

2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles from Streptococcus suis (S. suis)

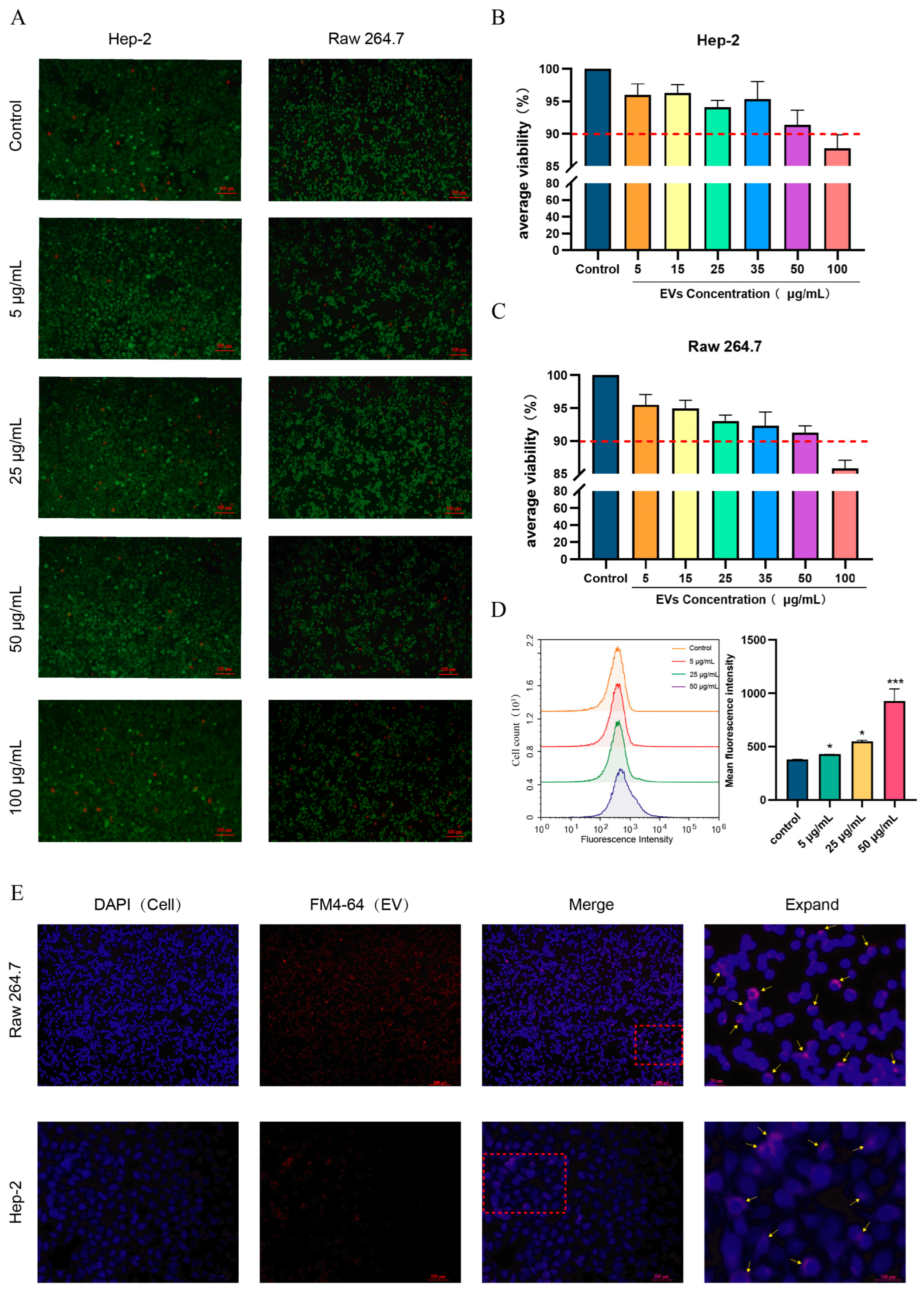

3.2. S. suis EVs Are Internalized by Epithelial Cells (HEp-2) and Macrophages (RAW264.7) and Do Not Affect Cell Activity

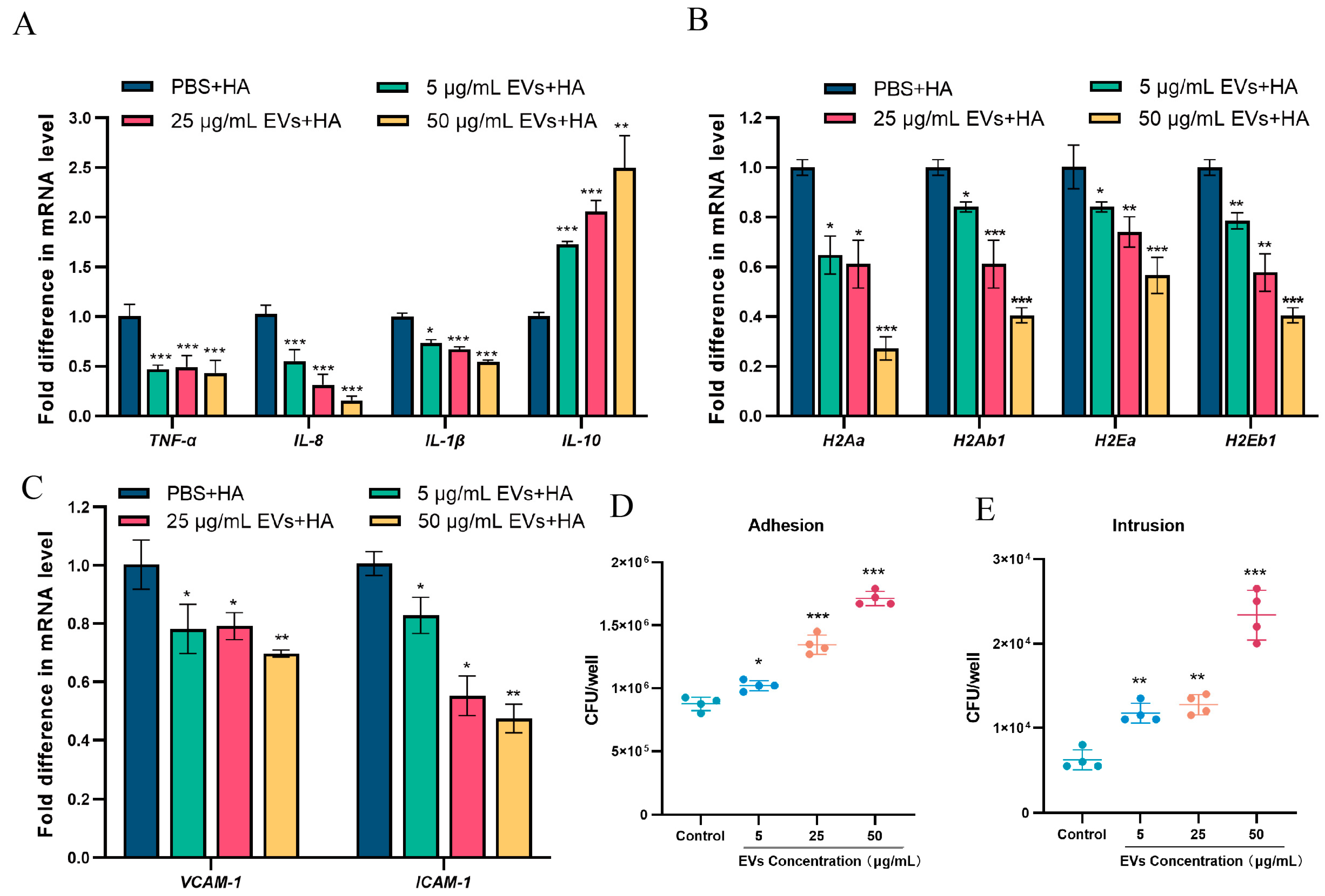

3.3. S. suis EVs Inhibit the Production of Cytosolic Pro-Inflammatory Factors, Reduce the Expression of MHC-II and Adhesion Molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1), and Promote the Adhesive Invasion of S. suis

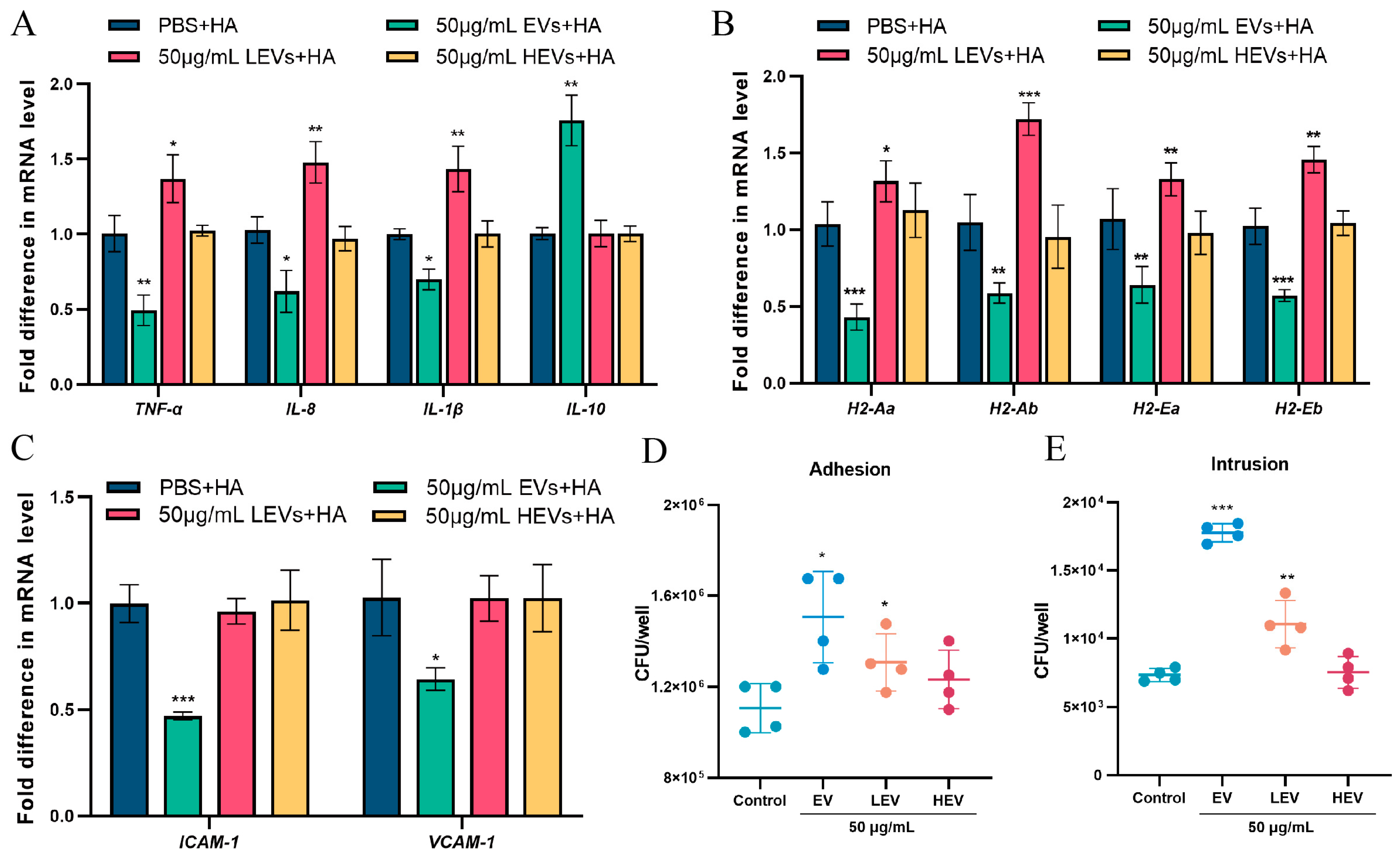

3.4. Only EVs with Intact Membrane Structures Function as Carriers to Deliver Contents into Cells

3.5. The Internalization of S. suis EVs Induces Metabolic Changes in Macrophages

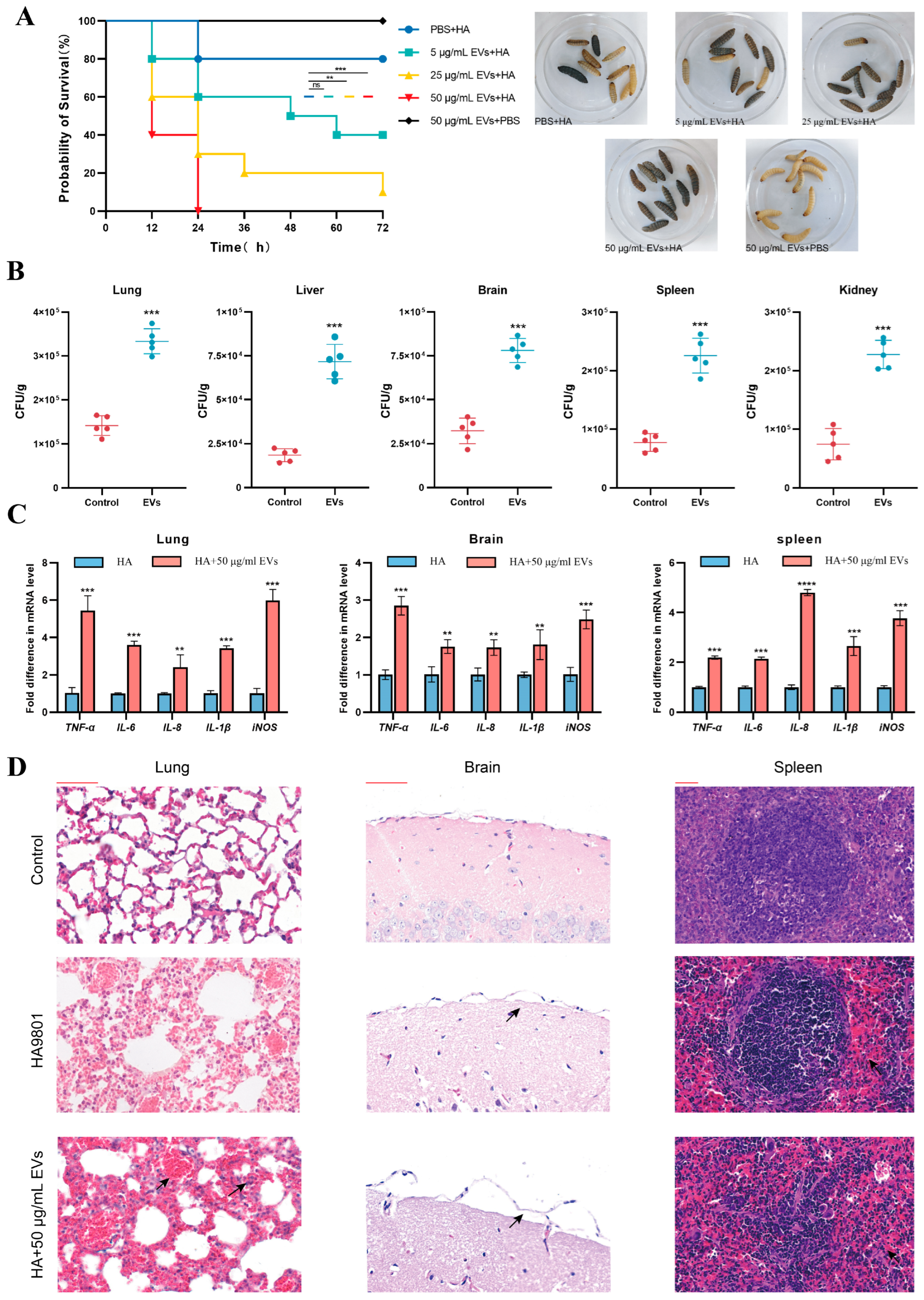

3.6. Animal Model to Assess the Effect of Extracellular Vesicles on the Pathogenicity of S. suis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wangkaew, S.; Chaiwarith, R.; Tharavichitkul, P.; Supparatpinyo, K. Streptococcus suis infection: A series of 41 cases from Chiang Mai University Hospital. J. Infect. 2006, 52, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertheim, H.F.; Nghia, H.D.; Taylor, W.; Schultsz, C. Streptococcus suis: An emerging human pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yi, L.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Mao, C.; Wang, Y. Autoinducer-2 influences tetracycline resistance in Streptococcus suis by regulating the tet(M) gene via transposon Tn916. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 128, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Jing, H.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Zu, R.; Luo, L.; et al. Human Streptococcus suis outbreak, Sichuan, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyette-Desjardins, G.; Calzas, C.; Shiao, T.C.; Neubauer, A.; Kempker, J.; Roy, R.; Gottschalk, M.; Segura, M. Protection against Streptococcus suis Serotype 2 Infection Using a Capsular Polysaccharide Glycoconjugate Vaccine. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyofuku, M.; Schild, S.; Kaparakis-Liaskos, M.; Eberl, L. Composition and functions of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, A.; Takeuchi, H.; Furuta, N. Outer membrane vesicles function as offensive weapons in host-parasite interactions. Microbes Infect. 2010, 12, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.I. Pharmacological inhibition of endocytic pathways: Is it specific enough to be useful? Exocytosis Endocytosis 2008, 440, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codemo, M.; Muschiol, S.; Iovino, F.; Nannapaneni, P.; Plant, L.; Wai, S.N.; Henriques-Normark, B. Immunomodulatory Effects of Pneumococcal Extracellular Vesicles on Cellular and Humoral Host Defenses. mBio 2018, 9, e00559-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudenmaier, L.; Focken, J.; Schlatterer, K.; Kretschmer, D.; Schittek, B. Bacterial membrane vesicles shape Staphylococcus aureus skin colonization and induction of innate immune responses. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dai, J.; Zhuge, X. Exploiting membrane vesicles derived from avian pathogenic Escherichia coli as a cross-protective subunit vaccine candidate against avian colibacillosis. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, C.N.; Delpino, M.V.; Fossati, C.A.; Baldi, P.C. Outer membrane vesicles from Brucella abortus promote bacterial internalization by human monocytes and modulate their innate immune response. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, N.; Takeuchi, H.; Amano, A. Entry of Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles into epithelial cells causes cellular functional impairment. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 4761–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisatjaluk, R.; Kotwal, G.J.; Hunt, L.A.; Justus, D.E. Modulation of gamma interferon-induced major histocompatibility complex class II gene expression by Porphyromonas gingivalis membrane vesicles. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, C.; Han, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Yang, M.; Zuo, J.; Tang, Y.; et al. Unveiling a Novel Mechanism of Enhanced Secretion, Cargo Loading, and Accelerated Dynamics of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles Following Antibiotic Exposure. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Hu, X.; Gao, Z.; Li, G.; Fu, F.; Shang, X.; Liang, Z.; Shan, Y. Global transcriptomic response of Listeria monocytogenes exposed to Fingered Citron (Citrus medica L. var. sarcodactylis Swingle) essential oil. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Wu, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, H.; She, P. Bactericidal and anti-quorum sensing activity of repurposing drug Visomitin against Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence 2024, 15, 2415952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Qi, Y.; Wang, J.; Shi, Q.; Xie, X.; Zhou, C.; Ma, L. hsdS(A) regulated extracellular vesicle-associated PLY to protect Streptococcus pneumoniae from macrophage killing via LAPosomes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0099523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehanny, M.; Koch, M.; Lehr, C.M.; Fuhrmann, G. Streptococcal Extracellular Membrane Vesicles Are Rapidly Internalized by Immune Cells and Alter Their Cytokine Release. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Goes, A.; Garcia, R.; Panter, F.; Koch, M.; Müller, R.; Fuhrmann, K.; Fuhrmann, G. Biocompatible bacteria-derived vesicles show inherent antimicrobial activity. J. Control. Release 2018, 290, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Gong, S.; Dong, X.; Mao, C.; Yi, L. LuxS/AI-2 system is involved in fluoroquinolones susceptibility in Streptococcus suis through overexpression of efflux pump SatAB. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 233, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; He, P.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Chen, S.; Yu, Y.; Shao, J.; Wang, K.; Wu, Z.; Yao, H.; et al. SssP1, a Fimbria-like component of Streptococcus suis, binds to the vimentin of host cells and contributes to bacterial meningitis. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18, e1010710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorev, D.S.; Tang, H.; Rouse, S.L.; Bolla, J.R.; von Kügelgen, A.; Baker, L.A.; Wu, D.; Gault, J.; Grünewald, K.; Bharat, T.A.M.; et al. The use of sonicated lipid vesicles for mass spectrometry of membrane protein complexes. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 1690–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husna, A.U.; Wang, N.; Cobbold, S.A.; Newton, H.J.; Hocking, D.M.; Wilksch, J.J.; Scott, T.A.; Davies, M.R.; Hinton, J.C.; Tree, J.J.; et al. Methionine biosynthesis and transport are functionally redundant for the growth and virulence of Salmonella Typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 9506–9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shi, Q.; He, Q.; Chen, G. Metabolomic insights into the inhibition mechanism of methyl N-methylanthranilate: A novel quorum sensing inhibitor and antibiofilm agent against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 358, 109402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Breitkopf, S.B.; Yang, X.; Asara, J.M. A positive/negative ion-switching, targeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics platform for bodily fluids, cells, and fresh and fixed tissue. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hui, F.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Spigelman, A.F.; MacDonald, P.E.; Wishart, D.S.; Li, S.; et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W398–W406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, N.; Kavanagh, K.; Wells, J.M. Evaluation of Galleria mellonella larvae for studying the virulence of Streptococcus suis. BMC Microbiol 2016, 16, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Mao, C.; Yuan, S.; Quan, Y.; Jin, W.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yi, L.; Wang, Y. AI-2 quorum sensing-induced galactose metabolism activation in Streptococcus suis enhances capsular polysaccharide-associated virulence. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reith, W.; LeibundGut-Landmann, S.; Waldburger, J.M. Regulation of MHC class II gene expression by the class II transactivator. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzat, V.; Macedo Rogero, M.; Noel Keane, K.; Curi, R.; Newsholme, P. Glutamine: Metabolism and Immune Function, Supplementation and Clinical Translation. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, E.L.; O’Neill, L.A. Reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism in macrophages as an anti-inflammatory signal. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 46, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, T.L.; Bayles, D.O. Comparative virulence and antimicrobial resistance distribution of Streptococcus suis isolates obtained from the United States. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1043529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Qin, W.; Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J.; Hu, J. How Streptococcus suis serotype 2 attempts to avoid attack by host immune defenses. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, K.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, K.; Gou, H.; Li, C.; Zhai, S. Membrane vesicles derived from Streptococcus suis serotype 2 induce cell pyroptosis in endothelial cells via the NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD pathway. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 1338–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz Aziziraftar, S.; Bahrami, R.; Hashemi, D.; Shahryari, A.; Ramezani, A.; Ashrafian, F.; Siadat, S.D. The beneficial effects of Akkermansia muciniphila and its derivatives on pulmonary fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolaki, M.; Armaka, M.; Victoratos, P.; Kollias, G. Cellular mechanisms of TNF function in models of inflammation and autoimmunity. Curr. Dir. Autoimmun. 2010, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, P.; Palucka, A.K.; Pascual, V.; Banchereau, J. Dendritic cells and cytokines in human inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008, 19, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosser, D.M.; Zhang, X. Interleukin-10: New perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunol. Rev. 2008, 226, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kaur, R.; Kumari, P.; Pasricha, C.; Singh, R. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1: Gatekeepers in various inflammatory and cardiovascular disorders. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 548, 117487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.H.; Fives-Taylor, P.M. Characteristics of adherence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans to epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 1994, 62, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, B.; Grenier, D. Isolation, Characterization and Biological Properties of Membrane Vesicles Produced by the Swine Pathogen Streptococcus suis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Xia, X.; Sun, C.; Feng, X.; Gu, J.; Du, C.; et al. Enolase of Streptococcus Suis Serotype 2 Enhances Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability by Inducing IL-8 Release. Inflammation 2016, 39, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerneni, S.S.; Werner, S.; Azambuja, J.H.; Ludwig, N.; Eutsey, R.; Aggarwal, S.D.; Lucas, P.C.; Bailey, N.; Whiteside, T.L.; Campbell, P.G.; et al. Pneumococcal Extracellular Vesicles Modulate Host Immunity. mBio 2021, 12, e0165721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Xia, Y.; Chen, S.; Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W.; Zhou, B.; Tan, B.; Zhu, G.; Deng, J.; Yin, Y. Glutamine Metabolism in Macrophages: A Novel Target for Obesity/Type 2 Diabetes. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiani, P.; Boraschi, D. From Monocytes to M1/M2 Macrophages: Phenotypical vs. Functional Differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liang, H.; Zen, K. Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage m1-m2 polarization balance. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, P.K.; Shibata, M.; Horng, T. Metabolism Supports Macrophage Activation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergadi, E.; Ieronymaki, E.; Lyroni, K.; Vaporidi, K.; Tsatsanis, C. Akt Signaling Pathway in Macrophage Activation and M1/M2 Polarization. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.; Khurasany, M.; Nguyen, T.; Kim, J.; Guilford, F.; Mehta, R.; Gray, D.; Saviola, B.; Venketaraman, V. Glutathione and infection. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 3329–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazy, M.; Kaminski, P.M.; Mao, K.; Tan, J.; Wolin, M.S. S-Nitroglutathione, a product of the reaction between peroxynitrite and glutathione that generates nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 32009–32015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, S.; Merkel, B.J.; Caffrey, R.; McCoy, K.L. Defective antigen processing correlates with a low level of intracellular glutathione. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996, 26, 3015–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhasselt, V.; Vanden Berghe, W.; Vanderheyde, N.; Willems, F.; Haegeman, G.; Goldman, M. N-acetyl-L-cysteine inhibits primary human T cell responses at the dendritic cell level: Association with NF-kappaB inhibition. J. Immunol. 1999, 162, 2569–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Huang, S.C.; Sergushichev, A.; Lampropoulou, V.; Ivanova, Y.; Loginicheva, E.; Chmielewski, K.; Stewart, K.M.; Ashall, J.; Everts, B.; et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity 2015, 42, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, L.A. A critical role for citrate metabolism in LPS signalling. Biochem. J. 2011, 438, e5–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciotti, E.; FitzGerald, G.A. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 986–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, P.S.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Chao, T.; Teav, T.; Christen, S.; Di Conza, G.; Cheng, W.C.; Chou, C.H.; Vavakova, M.; et al. α-ketoglutarate orchestrates macrophage activation through metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Lee, K. Metabolic influence on macrophage polarization and pathogenesis. BMB Rep. 2019, 52, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| H2-Ab1-F | CAGTGACAGATTTCTACCCAG |

| H2-Ab1-R | GTCCAGTCCCCATTCCTAA |

| H2-Aa-F | GCAGACGGTGTTTATGAGA |

| H2-Aa-R | AGAAGGGATGAAGGTGAGA |

| H2-Eb1-F | CTTCTACCCTGGCAACATT |

| H2-Eb1-R | CCACTCTGAGGAACCGTCT |

| H2-Ea-F | TCTTGGGTTGTTTGTGGGT |

| H2-Ea-R | CTCCTTGTCGGCGTTCTAC |

| TNF-α-F | CTCTTCTGTCTACTGAACTTCGGG |

| TNF-α-R | GGTGGTTTGTGAGTGTGAGGGT |

| IL-1β-F | TGTGATGTTCCCATTAGAC |

| IL-1β-R | AATACCACTTGTTGGCTTA |

| IL-10-F | TGCTATGCTGCCTGCTCTTA |

| IL-10-R | GGCAACCCAAGTAACCCTTA |

| IL-8-F | TGTTGAGCATGAAAAGCCTCTAT |

| IL-8-R | AGGTCTCCCGAATTGGAAAGG |

| iNOS-F | CACCCAGAAGAGTTACAGC |

| iNOS-R | GGAGGGAAGGGAGAATAG |

| Icam1-F | GATGGCAGCCTCTTATGTT |

| Icam1-R | GCTTGTCCCTTGAGTTTTA |

| Vcam1-F | CGTCATTATCTCCTGCAC |

| Vcam1-R | GTGCCTGGCGGATGGTGTA |

| GAPDH-F | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

| GAPDH-R | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, W.; Li, J.; Yi, Z.; Chang, Z.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Quan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Yi, L.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Streptococcus suis Promote Bacterial Pathogenicity by Disrupting Macrophage Metabolism. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2469. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112469

Jin W, Li J, Yi Z, Chang Z, Li Y, Shen Y, Quan Y, Wang Y, Liu B, Yi L, et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Streptococcus suis Promote Bacterial Pathogenicity by Disrupting Macrophage Metabolism. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2469. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112469

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Wenjie, Jinpeng Li, Zhaoyu Yi, Zhiheng Chang, Yue Li, Yamin Shen, Yingying Quan, Yuxin Wang, Baobao Liu, Li Yi, and et al. 2025. "Extracellular Vesicles from Streptococcus suis Promote Bacterial Pathogenicity by Disrupting Macrophage Metabolism" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2469. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112469

APA StyleJin, W., Li, J., Yi, Z., Chang, Z., Li, Y., Shen, Y., Quan, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, B., Yi, L., & Wang, Y. (2025). Extracellular Vesicles from Streptococcus suis Promote Bacterial Pathogenicity by Disrupting Macrophage Metabolism. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2469. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112469