Linking Soil Microbial Diversity to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Description

2.2. Laboratory Assays—14C and N

2.3. Laboratory Assay—33P

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

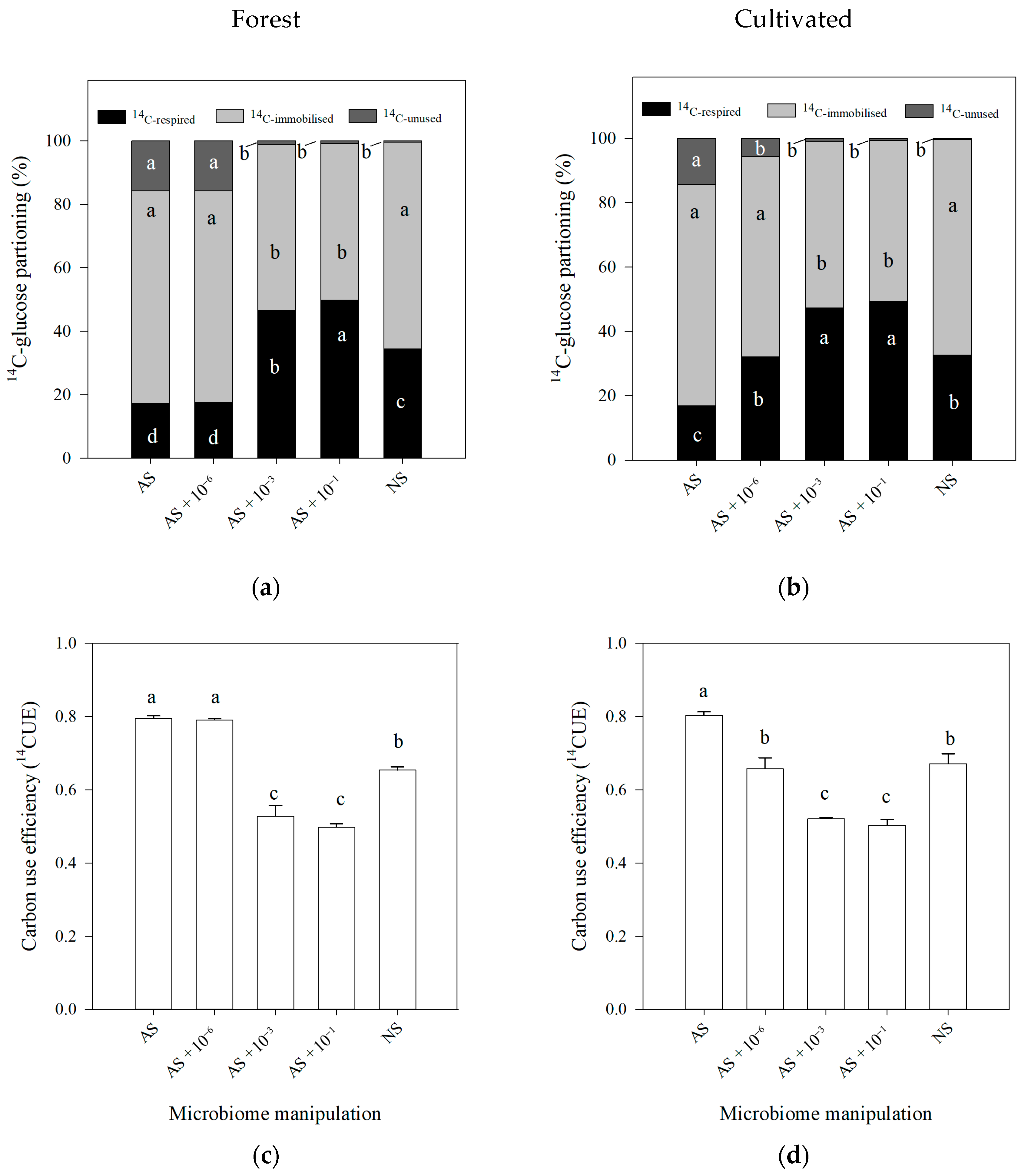

3.1. Microbial Activity Characterization—14C Approach

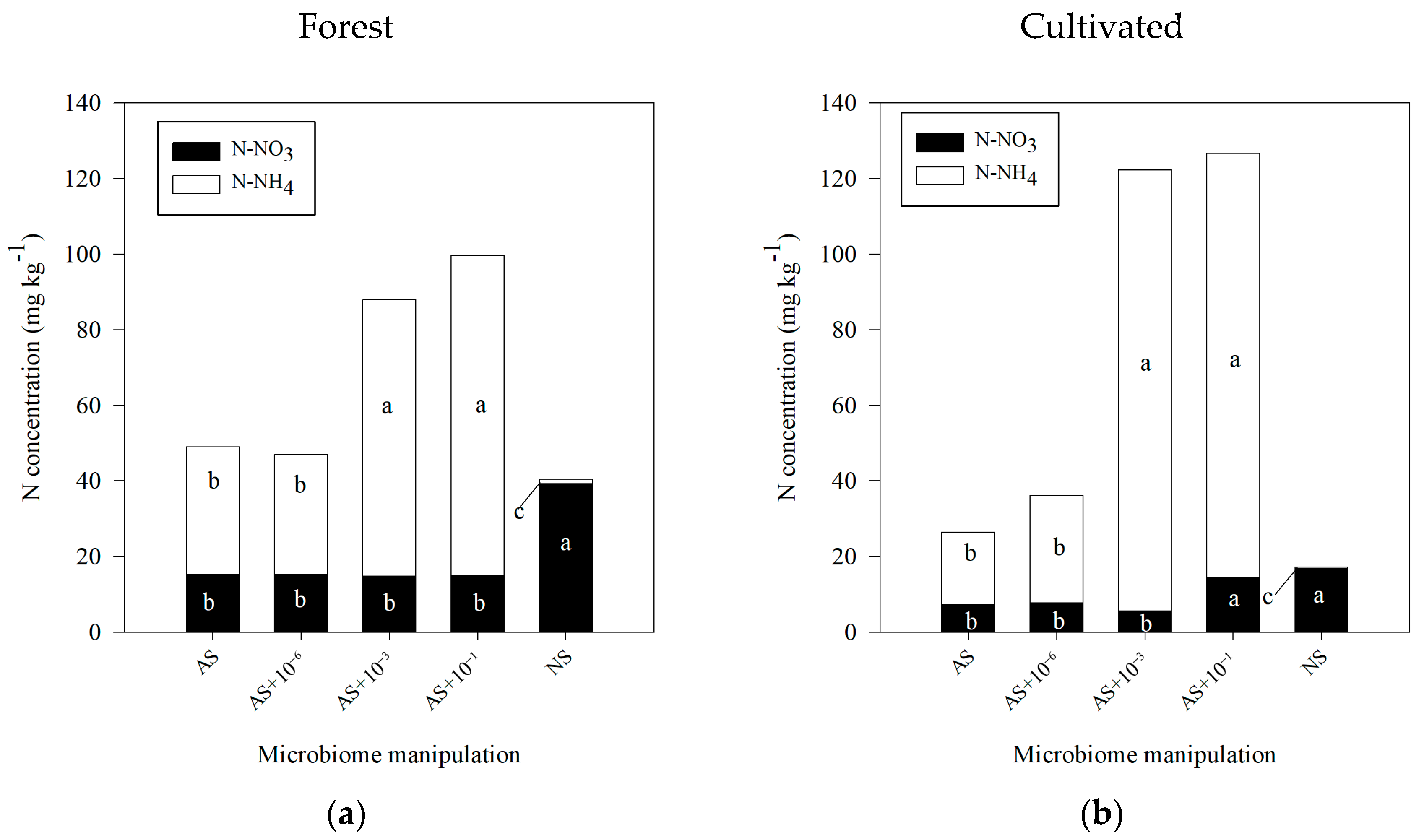

3.2. N Dynamics in Autoclaved Soil with the Levels of Microbial Reinoculation

3.3. P Dynamics in Autoclaved Soil with Levels of Microbial Reinoculation

4. Discussion

4.1. 14C and N Findings According to the Soil Manipulation Using Autoclaving

4.2. 33P Findings According to the Soil Manipulation Using Autoclaving

4.3. Limitations and Outlooks

4.4. Highlighting the Broader Implications of Microbial Manipulation Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NS | Non-autoclaved soil |

| AS | Autoclaved soil |

| AS + 10−1 | Autoclaved soil + wv−1 of NS added to the AS |

| AS + 10−3 | Autoclaved soil + wv−1 of NS added to the AS |

| AS + 10−6 | Autoclaved soil + wv−1 of NS added to the AS |

References

- Wu, H.; Cui, H.; Fu, C.; Li, R.; Qi, F.; Liu, Z.; Yang, G.; Xiao, K.; Qiao, M. Unveiling the crucial role of soil microorganisms in carbon cycling: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.M.; Fazila, Y.; Rahman, F.Z.U.; Yanli, L. Soil nitrogen dynamics in natural forest ecosystems: A review. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1144930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Ge, F.; Zhang, D.; Deng, S.; Liu, X. Roles of phosphate solubilizing microorganisms from managing soil phosphorus deficiency to mediating biogeochemical P cycle. Biology 2021, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-T.; Lu, J.-L.; Wang, H.-Y.; Fang, Z.; Wang, X.-J.; Feng, S.-W.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, S.-C.; Ou, S.-N.; et al. A comprehensive synthesis unveils the mysteries of phosphate-solubilizing microbes. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 2771–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, B.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Fei, H.; Pan, R.; Han, F. Plants use rhizosphere metabolites to regulate soil microbial diversity. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 5267–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: Diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Rodríguez, A.; Rangseekaew, P.; Lasudee, K.; Pathom-Aree, W.; Manzanera, M. Impacts of agriculture on the environment and soil microbial biodiversity. Plants 2021, 10, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennon, E.; Dari, B.; Jha, G.; Sihi, D.; Karnakala, V. Regenerative agriculture and integrative permaculture for sustainable and technology-driven global food production and security. Agron. J. 2021, 113, 4541–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossowicki, A.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Garbeva, P. Disentangling soil microbiome functions by perturbation. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 13, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLegge, M.J.; Manter, D.K.; Vivanco, J. Soil microbiome disruption used as a method to investigate specific and general plant–bacterial relationships in three agroecosystem soils. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, B.; George, P.B.L.; Robin, A.; Mescolotti, D.L.C.; Herrera, W.F.B.; Jones, D.L.; Andreote, F.D. Manipulation of the soil microbiome regulates the colonization of plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Zhu, B. Global patterns and associated drivers of priming effect in response to nutrient addition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 153, 108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.; Williams, A.P.; Miller, A.; Jones, D.L. Assessing the potential for ion selective electrodes and dual wavelength UV spectroscopy as a rapid on-farm measurement of soil nitrate concentration. Agriculture 2013, 3, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanville, H.C.; Hill, P.W.; Schnepf, A.; Oburger, E.; Jones, D.L. Combined use of empirical data and mathematical modelling to better estimate the microbial turnover of isotopically labelled carbon substrates in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 94, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Elsas, J.D.; Chiurazzi, M.; Mallon, C.A.; Elhottová, D.; Krištůfek, V.; Salles, J.F. Microbial diversity determines the invasion of soil by a bacterial pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, K.M.; Espey, M.G.; Wink, D.A. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide 2001, 5, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, R.L. Nitrogen-inorganic forms. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3. Chemical Methods, 3rd ed.; Sparks, D.L., Page, A.L., Helmke, P.A., Loeppert, R.H., Soltanpour, P.N., Tabatabai, M.A., Johnston, C.T., Sumner, M.E., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 1123–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Hedley, M.J.; Stewart, J.W.B.; Chauhan, B.S. Changes in inorganic and organic soil phosphorus fractions induced by cultivation practices and by laboratory incubations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1982, 46, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audi, G.; Bersillon, O.; Blachot, J.; Wapstra, A.H. The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties. Nucl. Phys. A 2003, 729, 3–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, D.; Marol, C.; Balesdent, J. The dynamics of neutral sugars in the rhizosphere of wheat: An approach by 13C pulse-labelling and GC/C/IRMS. Plant Soil 2004, 267, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascault, N.; Ranjard, L.; Kaisermann, A.; Bachar, D.; Christen, R.; Terrat, S.; Mathieu, O.; Lévêque, J.; Mougel, C.; Henault, C.; et al. Stimulation of different functional groups of bacteria by various plant residues as a driver of soil priming effect. Ecosystems 2013, 16, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, L.; Mougel, C.; Maron, P.; Nowak, V.; Lévêque, J.; Henault, C.; Haichar, F.e.Z.; Berge, O.; Marol, C.; Balesdent, J.; et al. Dynamics and identification of soil microbial populations actively assimilating carbon from 13C-labelled wheat residue as estimated by DNA- and RNA-SIP techniques. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, S.; Mariotti, A.; Abbadie, L. The priming effect of organic matter: A question of microbial competition? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Taylor, P.; Richter, A.; Porporato, A.; Ågren, G.I. Environmental and stoichiometric controls on microbial carbon-use efficiency in soils. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domsch, K.H.; Jagnow, G.; Anderson, T.H. An ecological concept for the assessment of side-effects of agrochemicals on soil microorganisms. In Residue Reviews: Residues of Pesticides and Other Contaminants in the Total Environment; Gunther, F.A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 65–105. [Google Scholar]

- Serrasolsas, I.; Khanna, P.K. Changes in heated and autoclaved forest soils of SE Australia. II. Phosphorus and phosphatase activity. Biogeochemistry 1995, 29, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, G.; Lucchesi, L.; Giachetti, M. Beneficial and detrimental Effects of Heating on soil Quality. In Fire in Ecosystem Dynamics: Mediterranean and Northern Perspectives; Goldammer, J.G., Jenkins, M.J., Eds.; SPB Academic Publishing: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, W.L.; Herman, D.J.; Firestone, M.K. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in upland tropical forest soils. Ecology 2001, 82, 2410–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Arenas, L.C.; Fusaro, C.; Hernández-Guzmán, M.; Dendooven, L.; Estrada-Torres, A.; Navarro-Noya, Y.E. Soil microbial diversity drops with land-use change in a high mountain temperate forest: A metagenomics survey. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 12, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.L.; Richards, S.C.; Kaminsky, L.M.; Bradley, B.A.; Kaye, J.P.; Bell, T.H. Leveraging microbiome rediversification for the ecological rescue of soil function. Environ. Microbiome 2023, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Land Use | pH | P | K | Mg | Ca | S | Mn | Cu | B | Zn | Mo | Fe | CEC * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ppm | meq/100 g | ||||||||||||

| Forest | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 17 ± 1 | 87 ± 2 | 133 ± 2 | 1149 ± 27 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 87 ± 8 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 0.74 ± 0.04 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 784 ± 46 | 11.0 ± 0.5 |

| Cultivated | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 36 ± 1 | 74 ± 3 | 70 ± 2 | 1851 ± 96 | 4.0 ± 0.0 | 94 ± 6 | 9.6 ± 0.5 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 854 ± 21 | 11.3 ± 0.5 |

| Microbiome Manipulation | Estimate | LL 2.50% | UL 97.50% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K parameter | ||||

| AS | 17.57 b | 16.92 | 18.24 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−6 | 21.41 b | 17.33 | 33.23 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−3 | 47.49 a | 45.11 | 50.10 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−1 | 49.01 a | 47.17 | 51.00 | 1.00 |

| NS | 31.35 b | 29.31 | 33.98 | 1.00 |

| r parameter | ||||

| AS | 2.45a | 1.65 | 3.24 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−6 | 1.88 ab | 0.01 | 3.29 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−3 | 0.21 b | 0.18 | 0.25 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−1 | 0.29 ab | 0.25 | 0.34 | 1.00 |

| NS | 0.45 a | 0.26 | 0.65 | 1.00 |

| b parameter | ||||

| AS | 0.06 ab | −0.07 | 0.17 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−6 | 1.33 ab | −0.06 | 6.41 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−3 | 5.42 a | 4.65 | 6.33 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−1 | 4.37 a | 3.88 | 4.91 | 1.00 |

| NS | 1.41 b | 0.95 | 2.08 | 1.00 |

| Microbiome Manipulation | Estimate | LL 2.50% | UL 97.50% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K parameter | ||||

| AS | 17.12 d | 16.53 | 17.74 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−6 | 35.52 b | 32.38 | 38.66 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−3 | 46.19 a | 44.67 | 47.83 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−1 | 47.11 a | 45.50 | 48.77 | 1.00 |

| NS | 29.90 c | 27.96 | 32.30 | 1.00 |

| r parameter | ||||

| AS | 2.56 a | 1.76 | 3.42 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−6 | 0.10 c | 0.08 | 0.13 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−3 | 0.36 b | 0.31 | 0.41 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−1 | 0.41 b | 0.35 | 0.48 | 1.00 |

| NS | 0.55 b | 0.33 | 0.80 | 1.00 |

| b parameter | ||||

| AS | 0.08 d | −0.04 | 0.18 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−6 | 5.65 a | 3.82 | 7.51 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−3 | 3.73 ab | 3.38 | 4.14 | 1.00 |

| AS + 10−1 | 3.35 b | 3.02 | 3.72 | 1.00 |

| NS | 1.25 c | 0.83 | 1.78 | 1.00 |

| Soil Microbiome Manipulation | 33PAER | 33PNaHCO3 | 33P0.1NaOH | 33PHCl | 33P0.5NaOH | 33PRes | 33PTotal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kBq | |||||||

| AS | 0.98 ± 0.04 b | 0.61 ± 0.03 b | 2.97 ± 0.04 a | 1.01 ± 0.05 a | 0.51 ± 0.02 a | 0.08 ± 0.00 ns | 6.16 ± 0.08 |

| AS + 10−6 | 1.00 ± 0.06 b | 0.59 ± 0.02 b | 3.02 ± 0.06 a | 1.01 ± 0.03 a | 0.52 ± 0.02 a | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 6.21 ± 0.16 |

| AS + 10−3 | 0.85 ± 0.06 c | 0.61 ± 0.02 b | 3.08 ± 0.06 a | 1.05 ± 0.05 a | 0.55 ± 0.02 a | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 6.21 ± 0.07 |

| AS + 10−1 | 0.80 ± 0.03 c | 0.59 ± 0.04 b | 3.03 ± 0.19 a | 1.04 ± 0.04 a | 0.55 ± 0.01 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 6.10 ± 0.25 |

| NS | 2.14 ± 0.13 a | 1.23 ± 0.13 a | 2.34 ± 0.14 b | 0.30 ± 0.02 b | 0.26 ± 0.03 b | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 6.31 ± 0.41 |

Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments. ns means not significant. Color scale was used for all sets of data for each variable. * 33P soil fractionation was determined according to Hedley et al. [18].

Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments. ns means not significant. Color scale was used for all sets of data for each variable. * 33P soil fractionation was determined according to Hedley et al. [18].| Soil Microbiome Manipulation | 33PAER | 33PNaHCO3 | 33P0.1NaOH | 33PHCl | 33P0.5NaOH | 33PRes | 33PTotal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kBq | |||||||

| AS | 1.51 ± 0.05 b | 0.59 ± 0.02 ns | 3.23 ± 0.10 a | 0.82 ± 0.03 ab | 0.34 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 ns | 6.54 ± 0.15 |

| AS + 10−6 | 1.57 ± 0.12 b | 0.81 ± 0.27 | 3.23 ± 0.11 a | 0.84 ± 0.07 a | 0.34 ± 0.03 a | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 6.83 ± 0.23 |

| AS + 10−3 | 1.66 ± 0.07 b | 0.80 ± 0.29 | 3.15 ± 0.13 ab | 0.74 ± 0.02 b | 0.34 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 6.75 ± 0.33 |

| AS + 10−1 | 1.70 ± 0.23 b | 0.58 ± 0.02 | 2.98 ± 0.16 b | 0.77 ± 0.04 ab | 0.37 ± 0.04 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 6.45 ± 0.04 |

| NS | 3.37 ± 0.13 a | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 1.79 ± 0.04 c | 0.18 ± 0.01 c | 0.12 ± 0.01 b | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 6.06 ± 0.11 |

Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments. ns means not significant. Color scale was used for all sets of data for each variable. * 33P soil fractionation was determined according to Hedley et al. [18].

Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments. ns means not significant. Color scale was used for all sets of data for each variable. * 33P soil fractionation was determined according to Hedley et al. [18].Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arruda, B.; Mariano, E.; Bejarano-Herrera, W.F.; Prataviera, F.; Hashimoto, E.M.; Putti, F.F.; Barcelos, J.P.d.Q.; Pavinato, P.S.; Andreote, F.D.; Jones, D.L. Linking Soil Microbial Diversity to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Dynamics. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102401

Arruda B, Mariano E, Bejarano-Herrera WF, Prataviera F, Hashimoto EM, Putti FF, Barcelos JPdQ, Pavinato PS, Andreote FD, Jones DL. Linking Soil Microbial Diversity to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Dynamics. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(10):2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102401

Chicago/Turabian StyleArruda, Bruna, Eduardo Mariano, Wilfrand Ferney Bejarano-Herrera, Fábio Prataviera, Elizabeth Mie Hashimoto, Fernando Ferrari Putti, Jéssica Pigatto de Queiroz Barcelos, Paulo Sergio Pavinato, Fernando Dini Andreote, and Davey L. Jones. 2025. "Linking Soil Microbial Diversity to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Dynamics" Microorganisms 13, no. 10: 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102401

APA StyleArruda, B., Mariano, E., Bejarano-Herrera, W. F., Prataviera, F., Hashimoto, E. M., Putti, F. F., Barcelos, J. P. d. Q., Pavinato, P. S., Andreote, F. D., & Jones, D. L. (2025). Linking Soil Microbial Diversity to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Dynamics. Microorganisms, 13(10), 2401. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102401