4. Results and Analysis

In this section, all simulations were performed in MATLAB/Simulink R2023b on a personal computer equipped with an Intel Core i7-10700KF CPU (3.80 GHz) and 32 GB of RAM while running a 64-bit Windows 11 operating system. A fixed-step Runge–Kutta (ode4) solver with a time step of 0.001 s was used to integrate the AUV dynamic model. The control algorithms and performance evaluation indices (IAE, ITAE, ISE, ITSE, and RMSE) were implemented and analyzed within the MATLAB environment.

In order to ensure a fair and reproducible comparison, all controllers (SMC, SMC-PSO, FSMC-PSO, and STA-PSO) were tested under identical simulation conditions. The hydrodynamic parameters used in the AUV model are listed in

Table 2, following the benchmark AUV formulation presented in [

10].

Table 3 presents the PSO parameters, control gain bounds, and final controller parameters.

In addition, to evaluate robustness, six levels of random disturbances (–) were applied to the system, generated as to emulate stochastic perturbations. All controllers were tested with the same initial conditions and reference trajectory. Performance indices (IAE, ITAE, ISE, ITSE, and RMSE) were computed over the full 40 s simulation to ensure a consistent comparison across all controllers.

The performance of the proposed FSMC-PSO strategy is evaluated through numerical simulations of the AUV system. The initial conditions of the AUV are set to

for position and heading, with the initial velocity

. The desired trajectory is defined as

, with its first and second derivatives given by

and

, respectively, following the formulation in [

10].

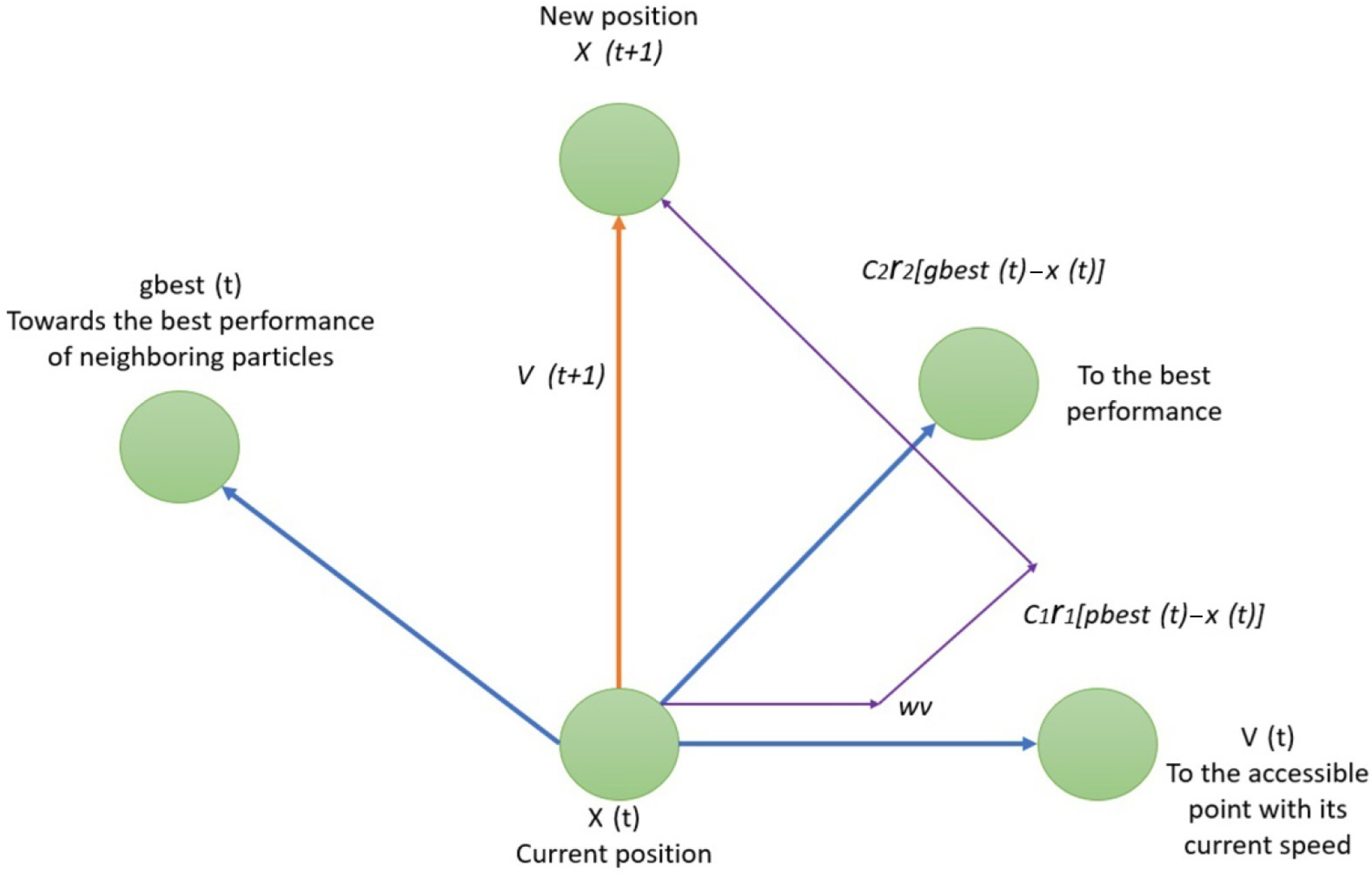

Figure 5 illustrates the convergence behavior of the PSO algorithm when applied to adjust the FSMC-PSO, STA-PSO, and SMC-PSO controllers. For the FSMC-PSO controller, the cost function decreases rapidly during the initial iterations, falling from approximately 51 to about 36 within the first 10 iterations. After this point, the convergence stabilizes, and the cost remains nearly constant, indicating fast and stable convergence behavior.

In the FSMC-PSO framework, a total of 18 output fuzzy membership function parameters are optimized offline, while the input membership functions of s and remain fixed. This design limits the dimensionality of the search space and contributes to the observed rapid convergence. A swarm size of 50 particles with 100 iterations is sufficient to achieve convergence with moderate computational requirements. During online operation, only the fuzzy inference mechanism is executed to adapt the sliding surface coefficients and switching gains k, resulting in negligible computational overhead.

For the STA-PSO controller, the cost function exhibits a very fast convergence behavior. The cost decreases sharply from an initial value of approximately 15 to below 2 within the first few iterations. After around 10 iterations, the optimization process reaches a steady state, and the cost remains nearly constant with negligible fluctuations. This rapid convergence demonstrates the effectiveness of PSO in tuning the super-twisting algorithm’s parameters and its ability to quickly identify a near-optimal solution.

Furthermore, the smooth and monotonic convergence profile of STA-PSO indicates reduced sensitivity to parameter oscillations during optimization. Compared to FSMC-PSO and SMC-PSO, STA-PSO achieves the lowest final cost value with fewer iterations, highlighting its superior convergence speed and robustness while maintaining high control performance.

For the SMC-PSO controller, the cost function decreases more gradually, starting from approximately 13 and converging to a final value near . Compared to FSMC-PSO and STA-PSO, the convergence process is slower and characterized by multiple stages of gradual reduction before stabilization, indicating higher sensitivity and computational effort during optimization.

Overall, although SMC-PSO achieves a lower final cost than FSMC-PSO, the STA-PSO controller demonstrates the fastest convergence and the lowest cost value, while FSMC-PSO provides a favorable balance between convergence speed, robustness, and computational efficiency.

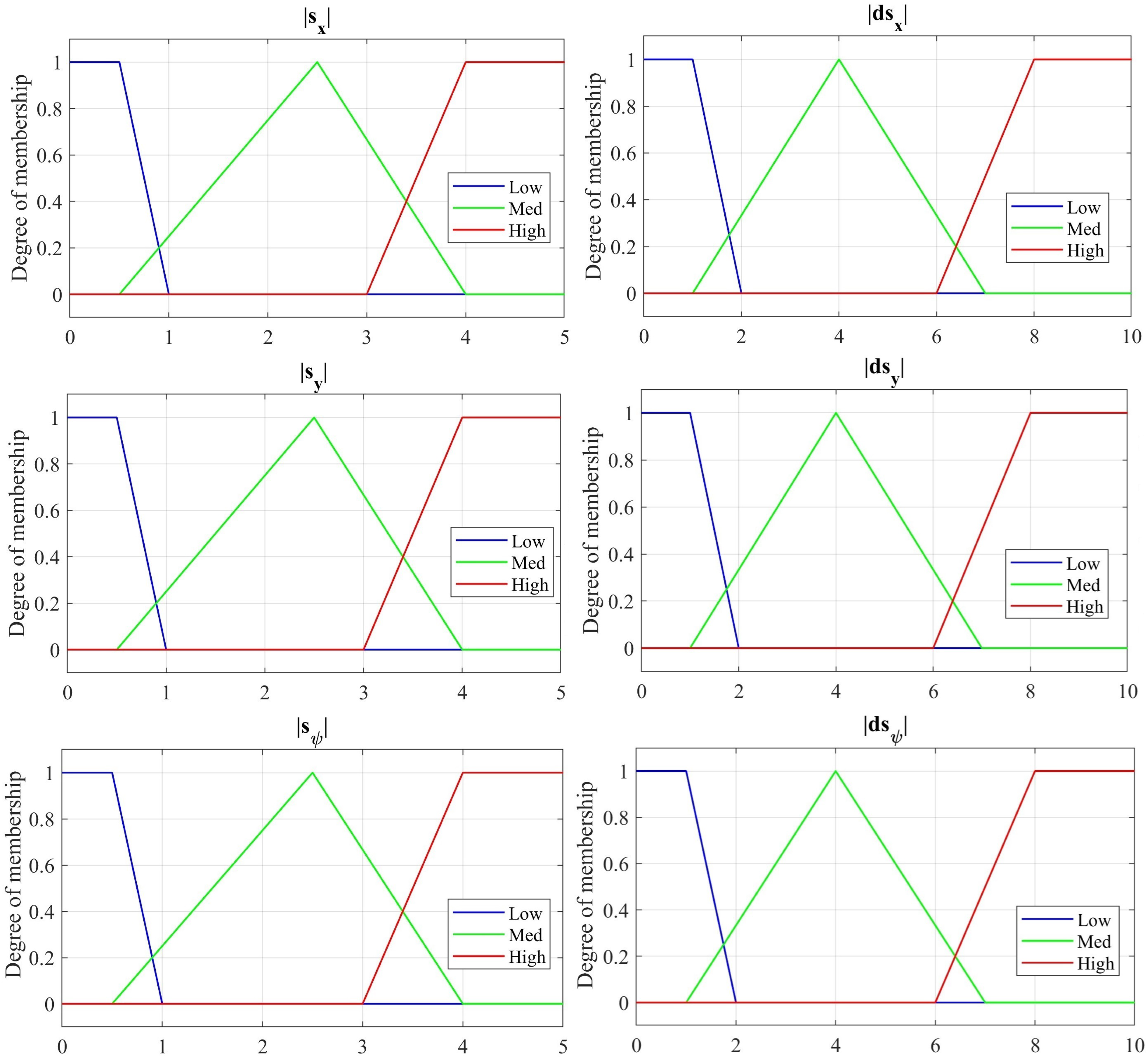

Figure 6 presents the optimized output membership functions associated with the fuzzy parameters

k and

, which exhibit a well-structured and heterogeneous partitioning of their respective universes of discourse.

The switching gains , , and are defined over relatively wide intervals using three triangular membership functions (Low, Medium, and High), allowing smooth transitions between low-switching actions for reduced chattering and high-switching actions for improved robustness against disturbances.

In contrast, the membership functions of , , and are distributed over narrower ranges, reflecting their role in fine-tuning the slope of the sliding surface. Lower values of yield smoother responses with reduced control effort, whereas higher values lead to faster convergence.

This heterogeneous distribution prevents redundancy among fuzzy sets and ensures smooth interpolation during inference while maintaining interpretability.

Overall, the optimized membership function design achieves a suitable balance between robustness and convergence speed.

The effectiveness of this optimized structure is further confirmed by the quantitative performance indices reported in

Table 4 and illustrated in

Figure 7.

FSMC-PSO consistently achieves the lowest values across all error indices (IAE, ITAE, ISE, ITSE, and RMSE) for the X, Y, and states, demonstrating superior tracking accuracy and disturbance rejection.

In summary, FSMC-PSO outperforms both SMC and SMC-PSO in terms of accuracy, robustness, and convergence behavior.

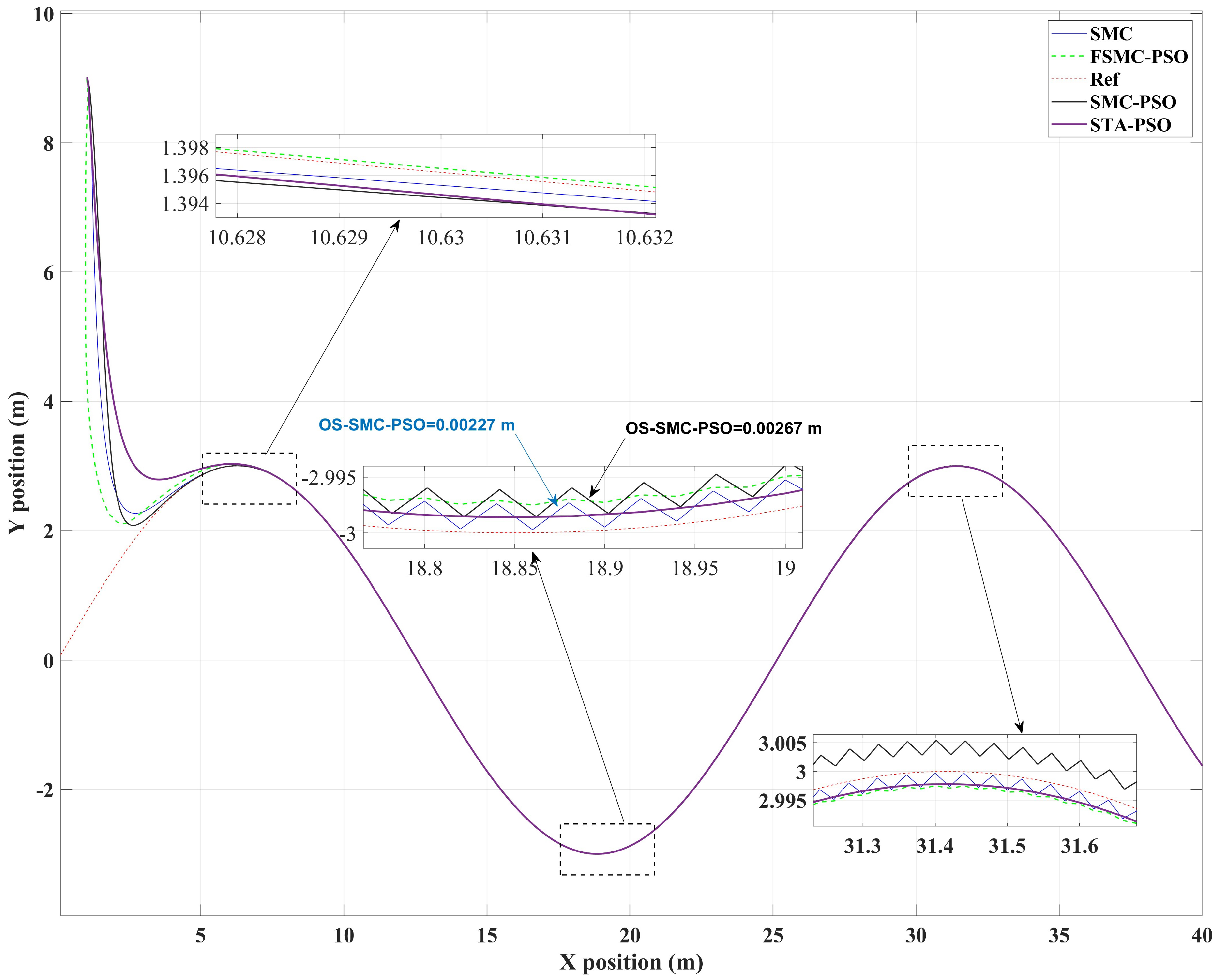

Figure 8 compares the planar motion of the AUV under FSMC-PSO, SMC-PSO, STA-PSO, and conventional SMC against the reference trajectory. The reference trajectory is a smooth nonlinear path with varying curvature and amplitude. Although all controllers are capable of following the desired path, noticeable differences in their dynamic responses can be observed.

During the transient phase (0–5 s), the conventional SMC exhibits a longer settling time accompanied by overshoot and oscillations, mainly due to the use of fixed switching gains. The SMC-PSO controller provides a moderate improvement by optimizing these gains offline, resulting in faster convergence toward the reference path. In contrast, the proposed FSMC-PSO controller achieves the fastest transient response, characterized by smooth convergence and minimal overshoot, and reaches steady-state tracking earlier than the other control strategies.

In the steady-state regime, FSMC-PSO demonstrates superior tracking accuracy and visibly reduced chattering compared to both SMC-PSO and conventional SMC. The zoomed views further highlight these improvements, where FSMC-PSO achieves a smaller overshoot ( m) compared to SMC ( m) and maintains smoother position regulation with negligible high-frequency oscillations.

At the valley near m and the crest around –32 m, the magnified windows show that FSMC-PSO remains closest to the reference envelope with minimal under- and overshoot, whereas SMC exhibits wider deviations, while SMC-PSO presents noticeable high-frequency ripples.

These ripples effectively increase the path length and introduce micro-limit cycles that degrade local tracking precision. Across the entire trajectory, the chattering amplitude follows a consistent order: SMC-PSO exhibits the largest high-frequency oscillations. SMC shows moderate ripples, and FSMC-PSO achieves the strongest attenuation of switching artifacts.

This behavior aligns with the intended effect of fuzzy adaptation, where lower gains are applied for small values of and , while higher gains are only activated for larger deviations, thereby smoothing the control action while preserving robustness. In contrast, direct PSO tuning of SMC tends to favor aggressive gain values, which improve nominal tracking accuracy but amplify switching activity and noise sensitivity.

The STA-PSO controller exhibits a different compromise between smoothness and tracking accuracy. STA-PSO significantly suppresses classical chattering and ensures a continuous control action. However, in regions with high curvature, such as near the valley at m and the crest around –32 m, STA-PSO shows a slight phase lag and a larger envelope deviation compared to FSMC-PSO. Although its steady-state response is smoother than conventional SMC, the absence of fuzzy gain adaptation limits its ability to simultaneously achieve fast transient convergence and tight steady-state tracking.

Overall, FSMC-PSO provides the best trade-off between accuracy, smoothness, and robustness, achieving faster transient convergence, smaller steady-state tracking errors, and significantly reduced chattering. These qualitative observations are consistent with the quantitative results reported in

Table 4, where FSMC-PSO achieves lower IAE, ITAE, ISE, ITSE, and RMSE values in

x,

y, and

.

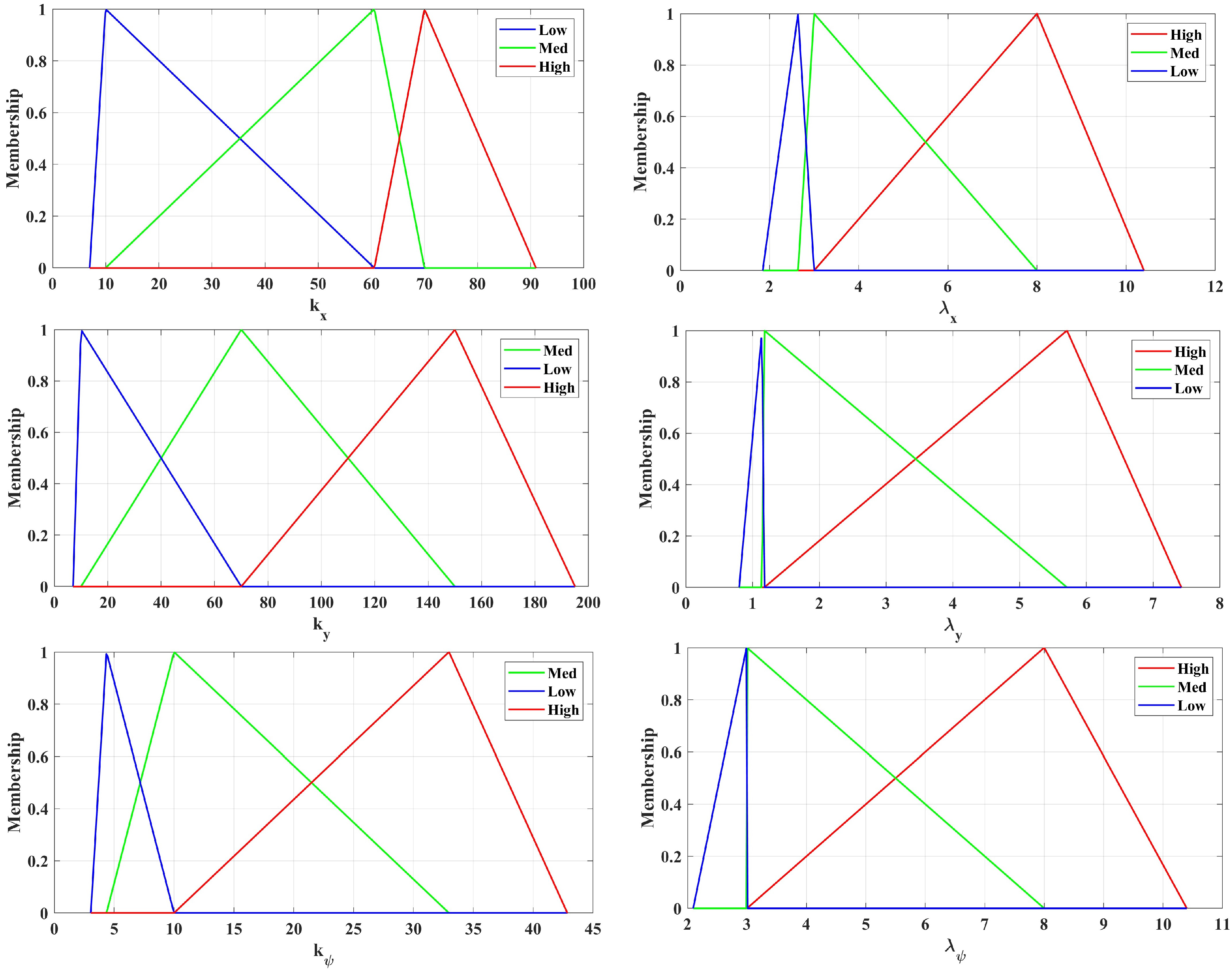

Figure 9 shows the time evolution of the SMC gains (

,

, and

) and the sliding surface parameters (

,

, and

) as adjusted online by the proposed FSMC-PSO controller. In all channels, the parameters exhibit a rapid transient adaptation phase during the first few seconds, followed by convergence to nearly constant steady-state values.

This behavior confirms that the PSO-optimized fuzzy rules effectively tune the controller parameters online, delivering strong corrective action during initial error regulation and stabilizing thereafter to avoid excessive switching activity.

For the surge and sway channels, the gains and initially reach relatively high peak values (approximately 60 and 150, respectively) to enforce rapid error convergence under large initial deviations.

These gains then decay rapidly to small steady-state levels once the tracking errors are reduced, indicating that the fuzzy adaptation mechanism suppresses unnecessary control effort after transient correction.

In contrast, the yaw gain converges to a moderate constant value around 10 with limited overshoot, reflecting the need for sustained corrective authority due to the AUV’s slower rotational dynamics.

The sliding surface parameters , , and exhibit a similar fast convergence behavior.

After an initial adjustment period of approximately 2–3 s, the parameters stabilize at constant values (, , ), forming well-conditioned sliding manifolds that balance convergence speed and robustness.

The absence of significant oscillations after convergence confirms that the FSMC–PSO scheme effectively avoids gain chattering and parameter drift, ensuring consistent closed-loop performance.

Overall, these results indicate that FSMC–PSO provides aggressive transient tuning in the presence of large errors, followed by smooth parameter stabilization during steady-state operation.

This adaptive behavior enhances trajectory precision while mitigating chattering, which is consistent with the reduced ripple observed in the trajectory plots and the superior performance indices reported in

Table 4.

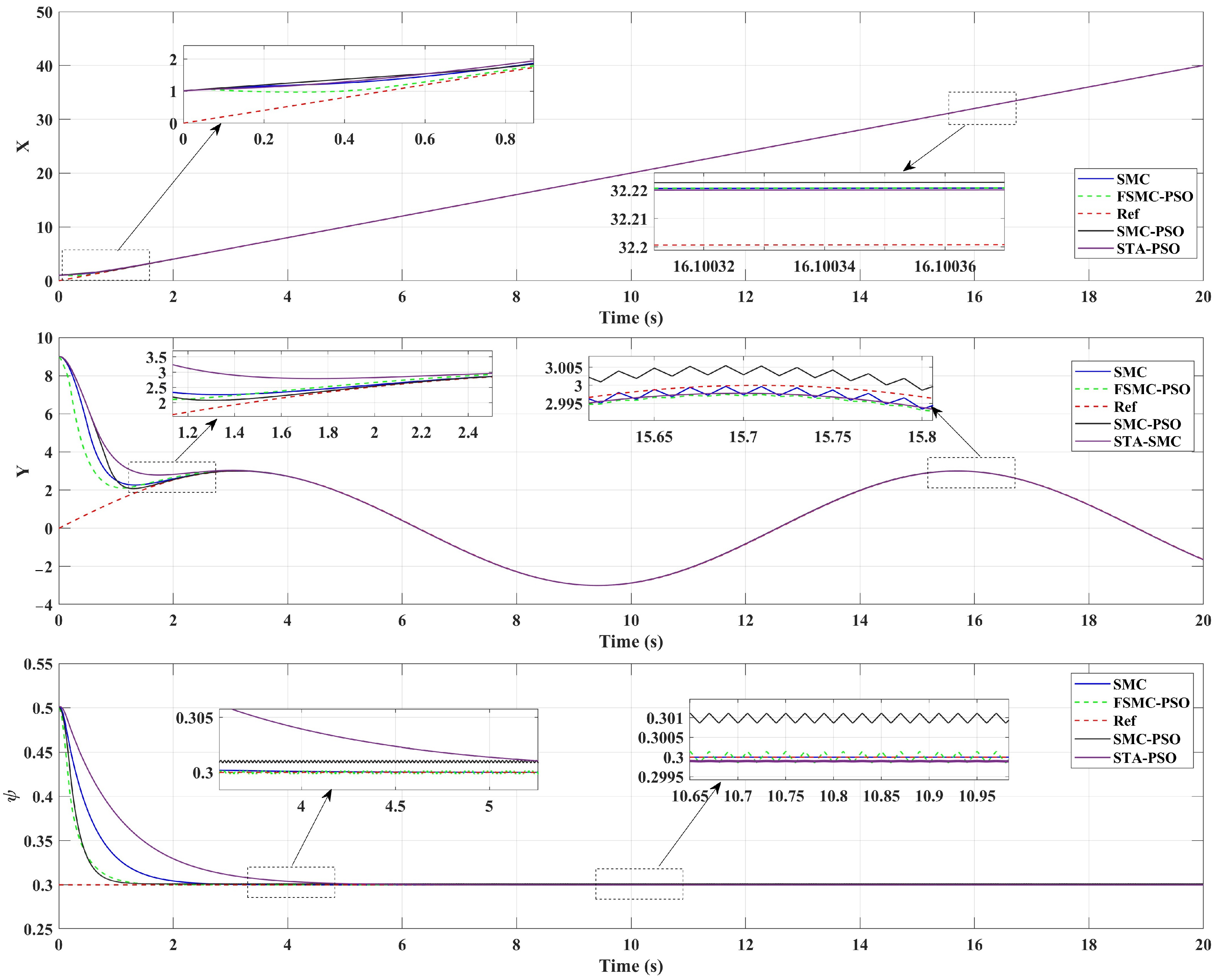

Figure 10 compares the position tracking performance of the

x,

y, and

coordinates under four control strategies: classical SMC, SMC tuned by PSO, STA-PSO, and the proposed FSMC-PSO approach. Although all controllers are able to follow the reference trajectory, noticeable differences arise in terms of the transient response, smoothness, and tracking precision.

For the surge motion (x trajectory), all controllers exhibit nearly identical tracking behavior, with the vehicle rapidly aligning with the desired linear reference. The tracking error converges within the first few seconds, indicating that the surge dynamics are relatively easy to regulate and require only limited enhancement from adaptive tuning strategies. The STA-PSO controller follows the reference accurately with smooth transient behavior, offering performance comparable to SMC-PSO and FSMC-PSO in the surge direction.

In contrast, for the sway motion (y trajectory), the benefits of adaptive tuning become more pronounced. The classical SMC exhibits a larger initial overshoot due to its fixed-gain structure, while SMC–PSO and FSMC-PSO significantly reduce this transient deviation through optimized parameter tuning. The STA-PSO controller also reduces the initial overshoot and provides a smoother response compared to classical SMC, although its convergence speed is slightly slower than that of FSMC-PSO. Among the four methods, FSMC-PSO achieves the smoothest convergence with minimal oscillations, reflecting its ability to adapt the sliding gains online and avoid over-aggressive control actions. Overall, both FSMC-PSO and STA-PSO enhance lateral tracking accuracy while maintaining improved motion smoothness.

For the yaw angle (), all controllers converge to the reference heading of approximately rad within about 2 s. FSMC-PSO demonstrates the fastest and smoothest settling behavior with minimal chattering, while STA-PSO also exhibits a smooth rotational response due to the super-twisting mechanism. In contrast, classical SMC shows higher steady-state oscillations caused by its discontinuous control action.

Overall, FSMC-PSO effectively combines the offline global optimization capability of PSO with the online local adaptability of fuzzy logic, resulting in a transient response that is both faster and smoother than classical SMC, SMC-PSO, and STA-PSO. These improvements are reflected in reduced tracking errors, improved disturbance rejection, and enhanced robustness during dynamic maneuvers.

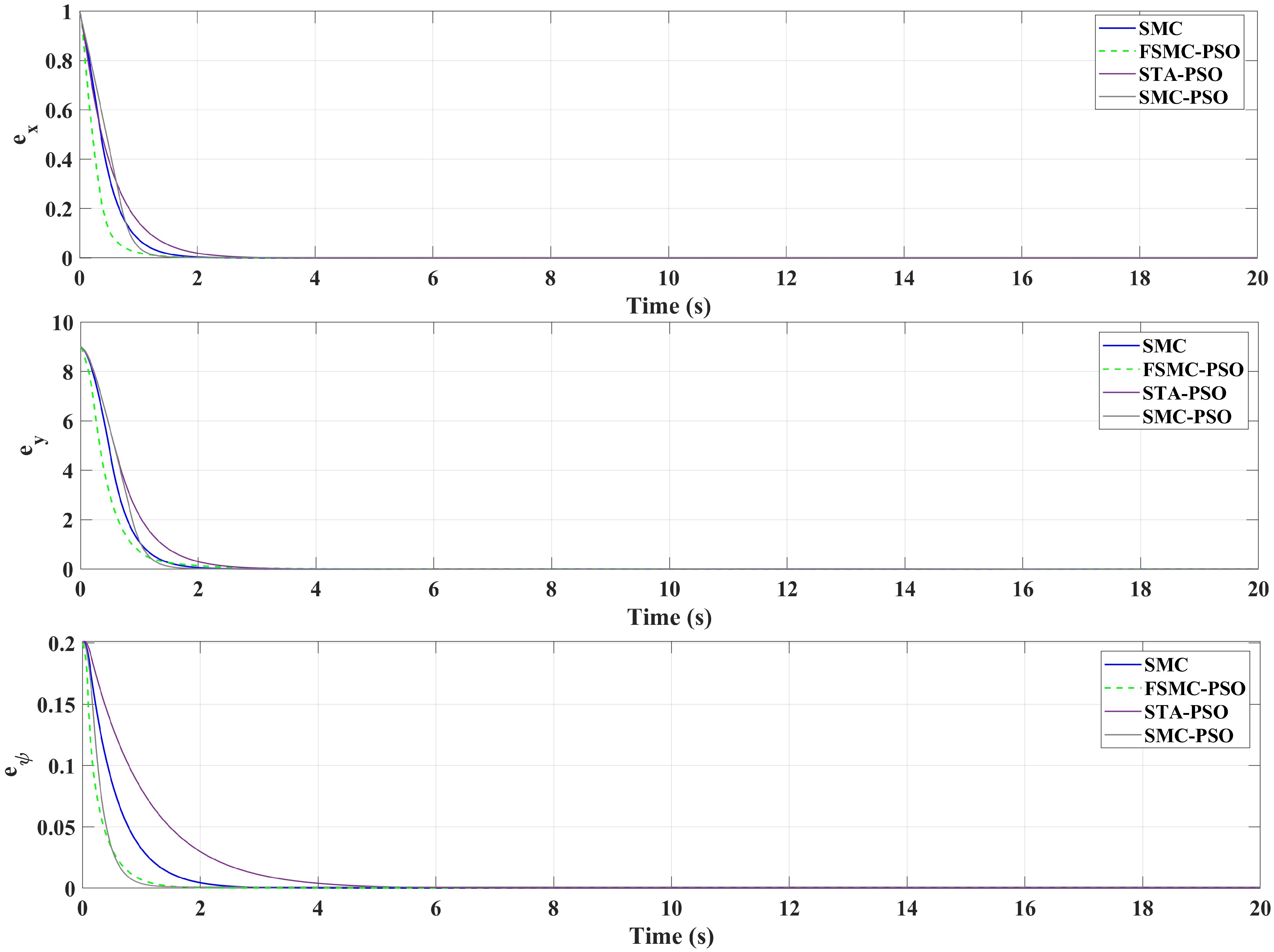

Figure 11 illustrates the tracking errors

,

, and

for the four controllers: FSMC-PSO, STA-PSO, SMC-PSO, and classical SMC. For all control strategies, the tracking errors converge rapidly toward zero, confirming the global stability of the closed-loop system. Nevertheless, noticeable differences are observed in the transient performance among the control schemes.

In the surge direction (), all controllers exhibit a fast exponential decay rate. FSMC-PSO achieves the fastest convergence, followed closely by SMC-PSO, while STA-PSO ensures stable convergence with a slightly slower decay rate but still outperforms the classical SMC. The adaptive approaches reduce the peak error and shorten the settling time to less than s, compared to approximately 2 s for the classical SMC.

In the sway direction (), the improvement offered by adaptive control is more pronounced. The classical SMC exhibits a higher initial deviation and slower error attenuation due to its fixed-gain structure. In contrast, FSMC-PSO and SMC-PSO provide steeper error decay and significantly reduced overshoot, while STA-PSO presents a smoother transient response with moderate convergence speed. All adaptive strategies, including STA-PSO, achieve near-zero error within approximately s, demonstrating superior lateral tracking precision compared to classical SMC.

For the yaw angle (), all controllers ensure rapid alignment with the desired heading. FSMC-PSO produces the smoothest transient response with minimal oscillations and reduced chattering. The STA-PSO controller also exhibits improved smoothness due to the super-twisting mechanism, whereas classical SMC shows more aggressive switching behavior.

Overall, these results validate that adaptive gain tuning through PSO and higher-order sliding mode techniques enhances the transient response, reduces peak tracking errors, and improves trajectory precision without compromising system stability. Among the evaluated strategies, FSMC-PSO achieves the best trade-off between convergence speed and smoothness, while STA-PSO provides a robust and smooth response with reduced chattering, and SMC-PSO offers a clear improvement over the baseline classical SMC.

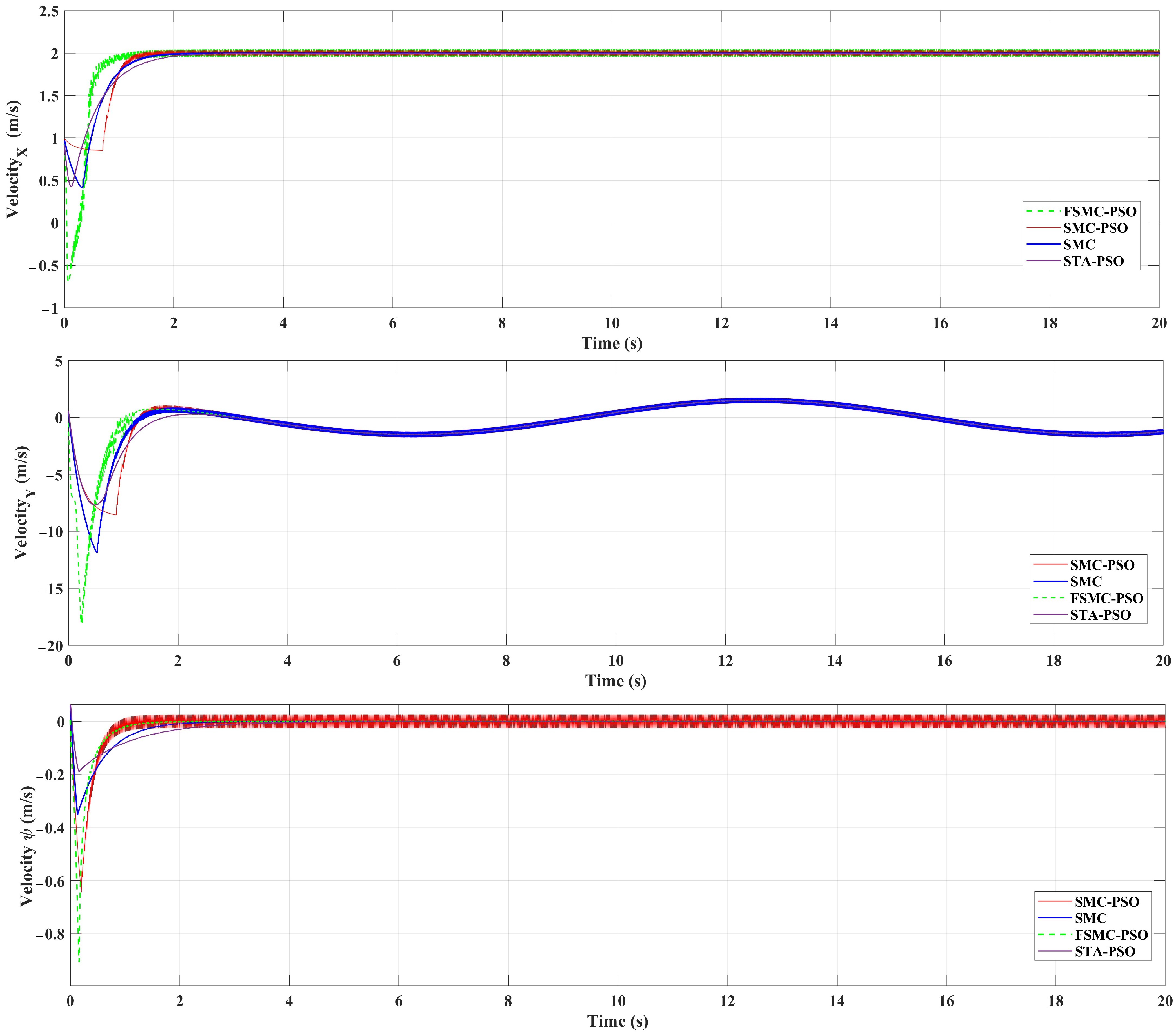

Figure 12 presents the velocity tracking performance of the AUV under four control schemes: FSMC-PSO, SMC-PSO, STA-PSO, and SMC. The responses correspond to the surge velocity

u (top), sway velocity

v (middle), and yaw rate

r (bottom), respectively. For the surge velocity

u, all controllers converge to the desired reference; however, clear differences appear in the transient behavior.

The adaptive scheme (FSMC-PSO) exhibits faster error attenuation and reduced initial overshoot compared to the classical SMC. In particular, FSMC-PSO achieves the shortest settling time (below s), followed by STA-PSO and SMC-PSO, whereas the classical SMC requires approximately 2 s to reach steady state, indicating slower transient convergence.

The sway velocity’s (v) response clearly highlights the advantage of adaptive and optimization-based control strategies. Classical SMC exhibits larger initial oscillations and a slower damping rate due to its fixed-gain structure and higher sensitivity to disturbances. In contrast, FSMC-PSO, SMC-PSO, and STA-PSO produce significantly smoother transients, with FSMC-PSO achieving the lowest peak deviation and the fastest stabilization, while STA-PSO shows improved damping compared to SMC-PSO but slightly slower convergence than FSMC-PSO. These improvements directly translate into enhanced lateral trajectory precision and reduced cross-track error during maneuvering.

For the yaw rate r, all four controllers demonstrate convergence with negligible steady-state error; however, their transient smoothness differs noticeably. FSMC-PSO achieves the most uniform transient response, effectively minimizing chattering and excessive switching activity typically associated with conventional SMC. STA-PSO also significantly attenuates chattering due to its continuous super-twisting structure, although slightly larger transient fluctuations are observed compared to FSMC-PSO.

Overall, these results demonstrate that integrating optimization-based tuning and fuzzy adaptation into the SMC framework substantially improves the transient response, reduces velocity tracking errors, and enhances motion smoothness without compromising closed-loop stability.

Among the evaluated controllers, FSMC-PSO provides the most favorable trade-off between convergence speed, overshoot suppression, chattering reduction, and control smoothness, making it particularly suitable for high-precision AUV velocity tracking tasks.

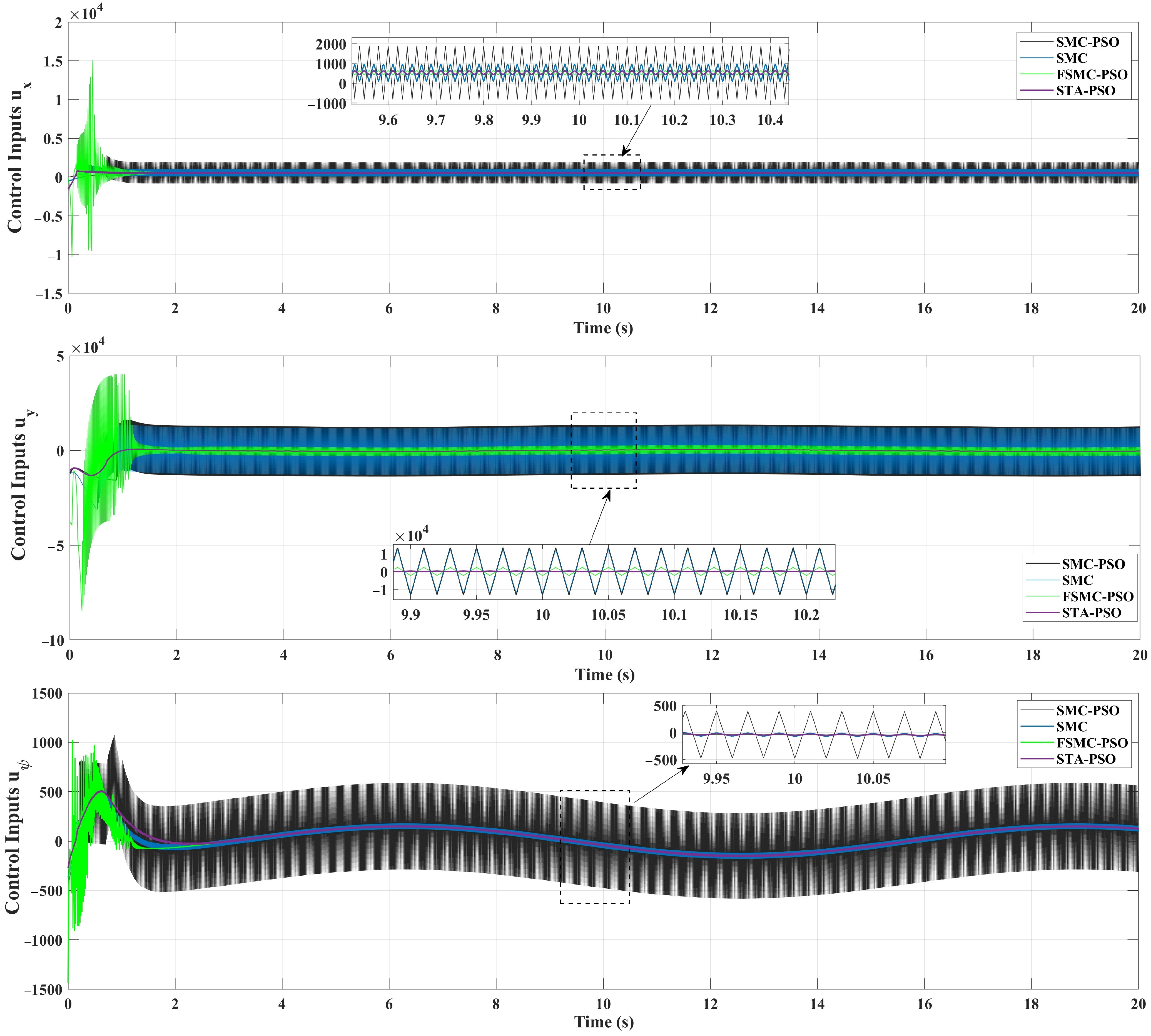

Figure 13 illustrates the control input signals generated under four different control strategies: FSMC-PSO, SMC-PSO, STA-PSO, and conventional SMC. For the FSMC-PSO strategy (top subplot), the control inputs initially exhibit a relatively high magnitude with noticeable oscillations during the transient phase (0–2 s). These oscillations are rapidly attenuated, and the control action converges to a smooth and stable profile with significantly reduced fluctuations after approximately 3 s. This behavior indicates that the combination of fuzzy adaptation and offline PSO tuning enhances robustness and effectively mitigates chattering.

For the classical SMC (middle subplot), the control inputs exhibit persistent oscillatory behavior throughout the entire simulation horizon. The control effort remains relatively large and does not fully settle, reflecting the well-known drawback of SMC, namely chattering caused by the discontinuous switching control law. Although closed-loop stability is achieved, the high-frequency oscillations imply increased actuator stress and reduced control efficiency.

The SMC-PSO strategy (bottom subplot) shows an improvement over classical SMC, with oscillations of lower amplitude and a smoother response, particularly after the transient phase. Nevertheless, residual chattering remains more pronounced than in FSMC-PSO, suggesting that PSO-based parameter optimization alone is insufficient to fully suppress the inherent switching effects of SMC.

The STA-PSO controller exhibits a markedly smoother control profile due to the continuous nature of the super-twisting algorithm. As observed in all three control channels, STA-PSO significantly reduces high-frequency oscillations compared to both SMC and SMC-PSO, resulting in bounded and continuous control inputs after the transient phase. However, during the initial response, the control effort of STA-PSO remains slightly higher than that of FSMC-PSO, and its convergence toward low-amplitude steady-state signals is comparatively slower. This behavior reflects the fixed-gain structure of STA-PSO, which, although effective in chattering suppression, lacks adaptive gain scheduling to further minimize control effort under small tracking errors.

Overall, the comparative results highlight that FSMC-PSO yields the most favorable control performance, achieving faster stabilization, lower control effort, and significant chattering suppression. By contrast, classical SMC suffers from sustained high-frequency oscillations, while SMC-PSO provides only moderate improvements and still lags behind both FSMC-PSO and STA-PSO in terms of control smoothness and efficiency.

Robustness Study

Figure 14 illustrates the position tracking performance of the proposed controllers under different levels of random noise disturbances. The desired trajectory is shown as a dashed red curve, while the actual tracking responses under various disturbance intensities (

to

) are represented by solid lines. In subplot (a), corresponding to the classical SMC, the trajectory tracking performance degrades noticeably as the noise intensity increases. Large deviations and oscillations are observed, particularly during transient phases and in the mid-trajectory region, indicating the high sensitivity of conventional SMC to stochastic disturbances.

In subplot (b), illustrating the performance of the SMC-PSO controller, moderate deviations from the desired trajectory are observed under high noise levels. The PSO-based optimization method improves robustness relative to classical SMC; however, residual tracking errors persist, especially in the mid-trajectory region, indicating limited noise rejection capability under severe disturbances.

In subplot (c), corresponding to the STA-PSO controller, improved tracking performance is achieved compared to SMC and SMC-PSO. The STA contributes to smoother trajectories and reduced chattering; however, noticeable deviations from the desired path still appear under high noise levels, especially during transient periods.

Subplot (d) illustrates the performance of the proposed FSMC-PSO controller. Trajectory tracking remains close to the desired path even in the presence of severe noise disturbances. Minor transient deviations are observed, but the controller effectively compensates for uncertainties and maintains accurate tracking, demonstrating superior robustness compared to the other control strategies.

Overall, the comparative results clearly indicate that FSMC-PSO achieves the highest tracking accuracy and robustness across all considered noise levels in the simulation. STA-PSO provides improved smoothness and disturbance rejection compared to SMC and SMC-PSO but remains less effective than FSMC-PSO in suppressing noise-induced deviations. Classical SMC exhibits the weakest disturbance rejection capability under stochastic disturbances.

These results are solely based on numerical simulations. Real-world factors, including ocean currents, actuator saturation, sensor noise, and communication delays, were not modeled. In addition, FSMC-PSO requires higher computational resources than SMC, SMC-PSO, and STA-PSO, which may impact real-time implementation. The applied random noise disturbances may also not fully represent realistic underwater conditions.

A comparative analysis is presented between the proposed FSMC-PSO controller and related control strategies reported in the literature, such as classical SMC, SMC-PSO, and STA-PSO. The FSMC-PSO controller offers several advantages: (1) the integration of conventional SMC, fuzzy logic, and PSO enhances overall trajectory tracking accuracy and robustness; (2) chattering is effectively suppressed through continuous adaptation of the switching gain k and sliding surface parameter based on the real-time tracking error; (3) the controller demonstrates improved disturbance rejection capability compared with conventional approaches; and (4) performance indices (IAE, ITAE, ISE, ITSE, and RMSE) are consistently reduced across all motion states, contributing to smoother control signals and increased actuator longevity.

Despite these advantages, several limitations are acknowledged: (1) The inclusion of the PSO process increases computational complexity compared with conventional SMC, particularly when online optimization is considered, thus requiring higher processing capacity or offline optimization. (2) The fuzzy inference system introduces additional design parameters that must be carefully tuned to maintain stability and performance. (3) Variations in external disturbances can lead to variations in the adaptive fuzzy outputs, which consequently alter the adaptive parameters k and . Such variations may increase sensitivity, complicate real-time tuning, and potentially degrade stability if not properly bounded. (4) The present validation strategy is based solely on numerical simulations, and experimental implementation is still required to confirm practical applicability.

Overall, the FSMC-PSO controller achieves a favorable balance between accuracy, robustness, and smoothness, making it a promising control strategy for high-precision AUV trajectory tracking within the considered simulation framework. In order to illustrate the disturbance rejection capability, the controllers’ tracking performance was evaluated under the representative disturbance of

randn(1,1), which is the level at which the baseline SMC begins to exhibit noticeable deviations.

Figure 14 shows the trajectories of all four controllers under this disturbance. It can be seen that FSMC-PSO maintains the closest tracking accuracy to the reference trajectory with minimal chattering, while SMC-PSO shows moderate deviations, and classical SMC exhibits significant tracking errors. This representative scenario highlights the superior robustness of the proposed FSMC-PSO controller.

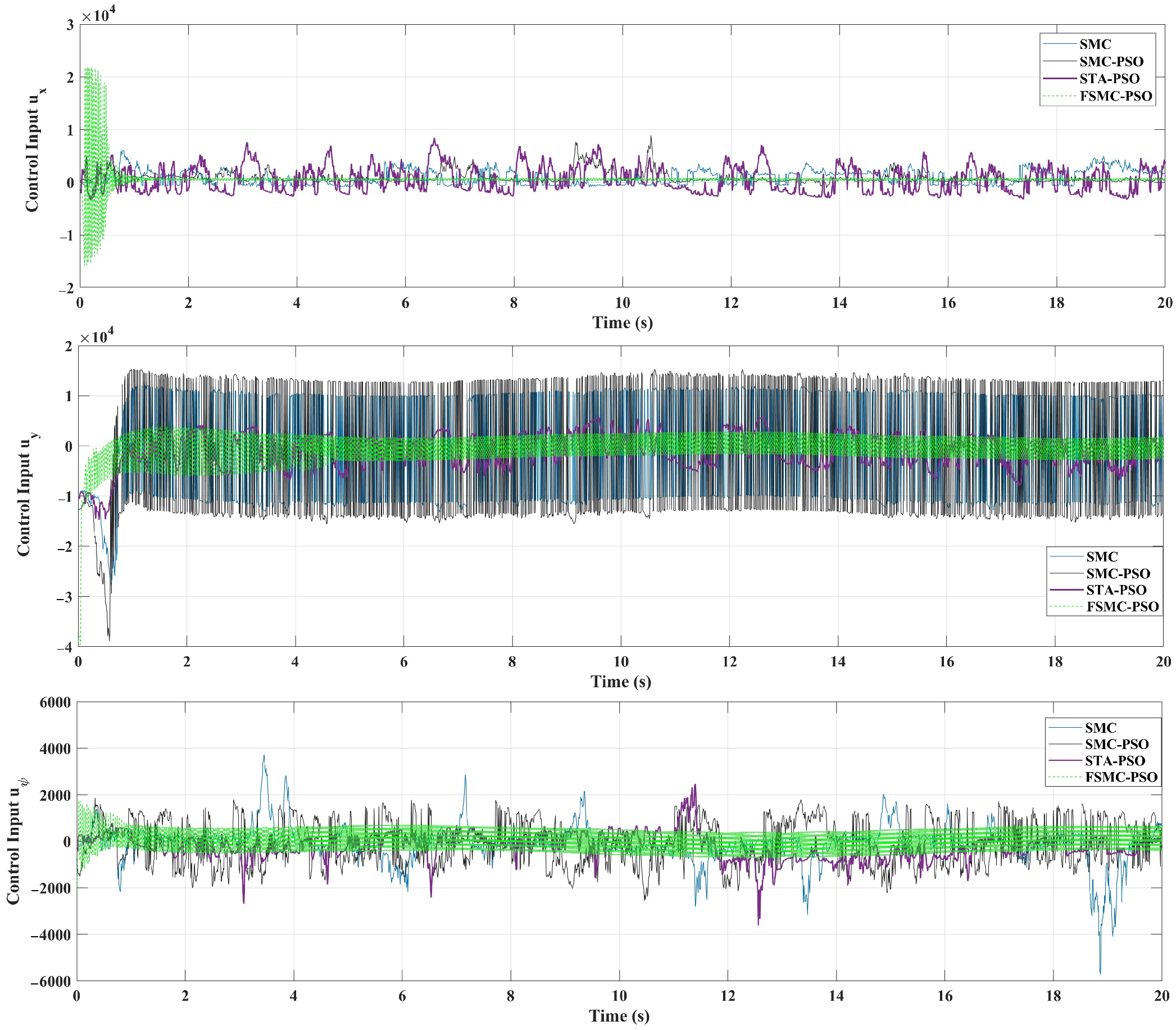

Figure 15 shows the control signals for FSMC-PSO, STA-PSO, SMC-PSO, and classical SMC under the representative the random disturbance of

randn(1,1). The FSMC-PSO controller exhibits smooth and robust control with minimal chattering, while SMC-PSO displays moderate fluctuations, and classical SMC shows significant oscillations. This illustrates the superior disturbance rejection capability of the proposed FSMC-PSO controller.