Magnetic Equivalent Circuit-Based Performance Evaluation of Modular PCB AFPM Motor for Electric Water Pumps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics

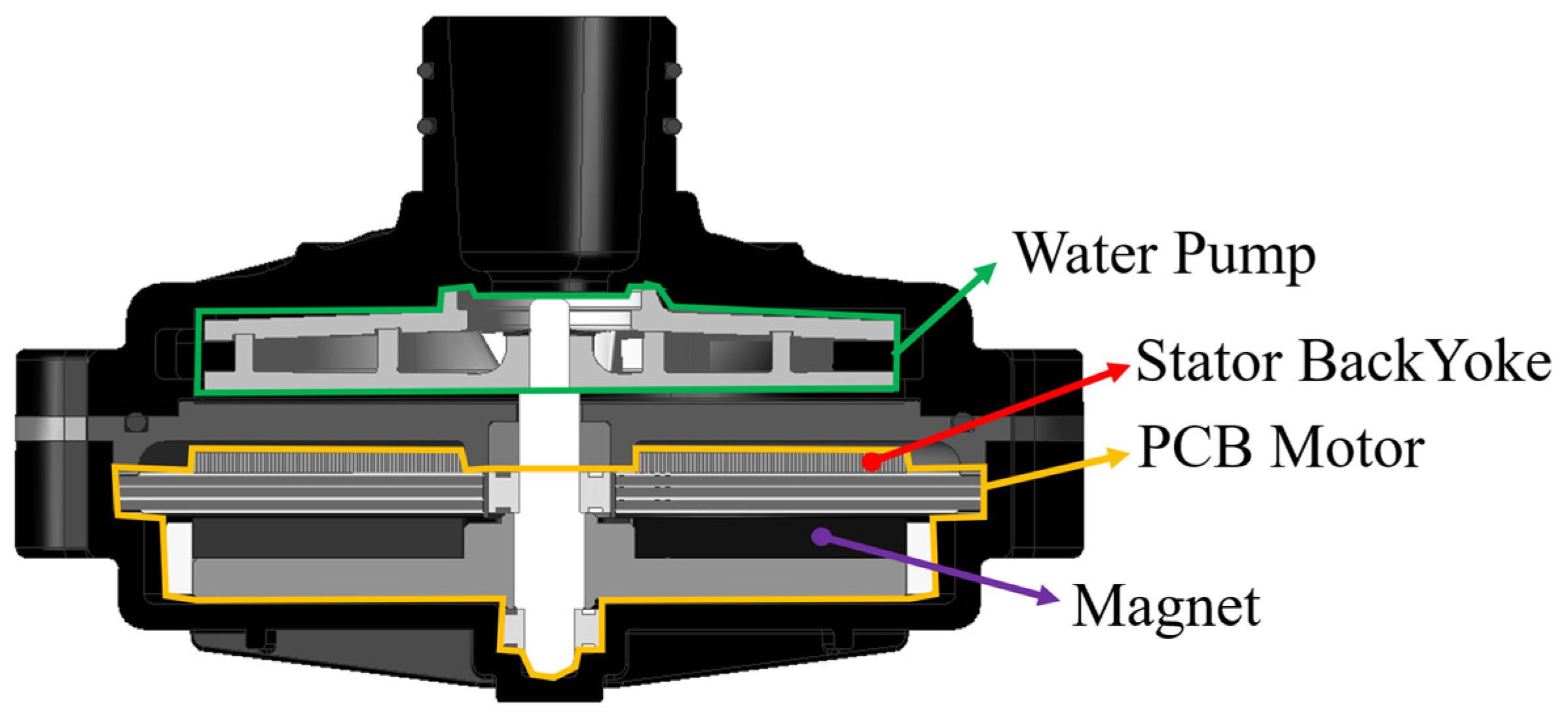

2.1. Machine Structure for EWP System

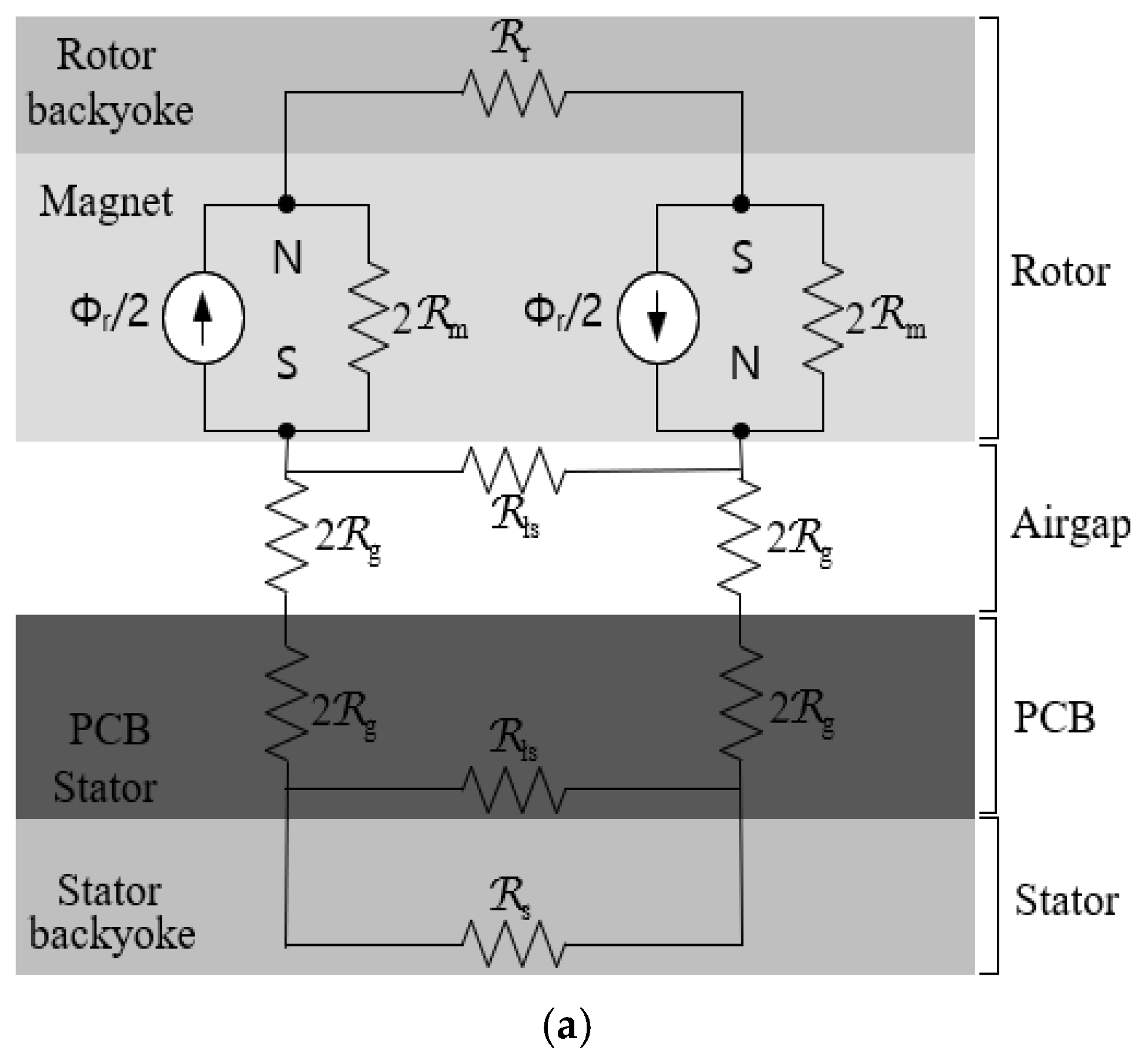

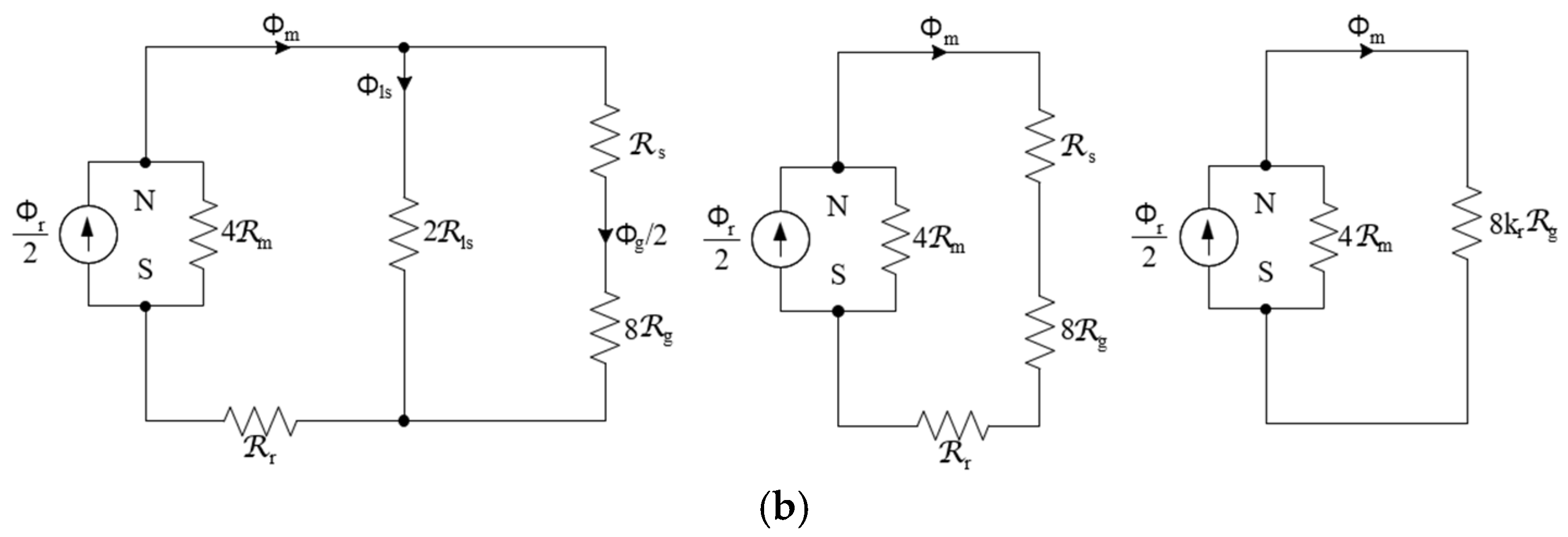

2.2. Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Model of PCB AFPM

2.3. Torque Analysis of Magnetic Equivalent Circuit (MEC) Modeling

3. Basic 3D FEA Model Design and Loss-Reduction Trace Design

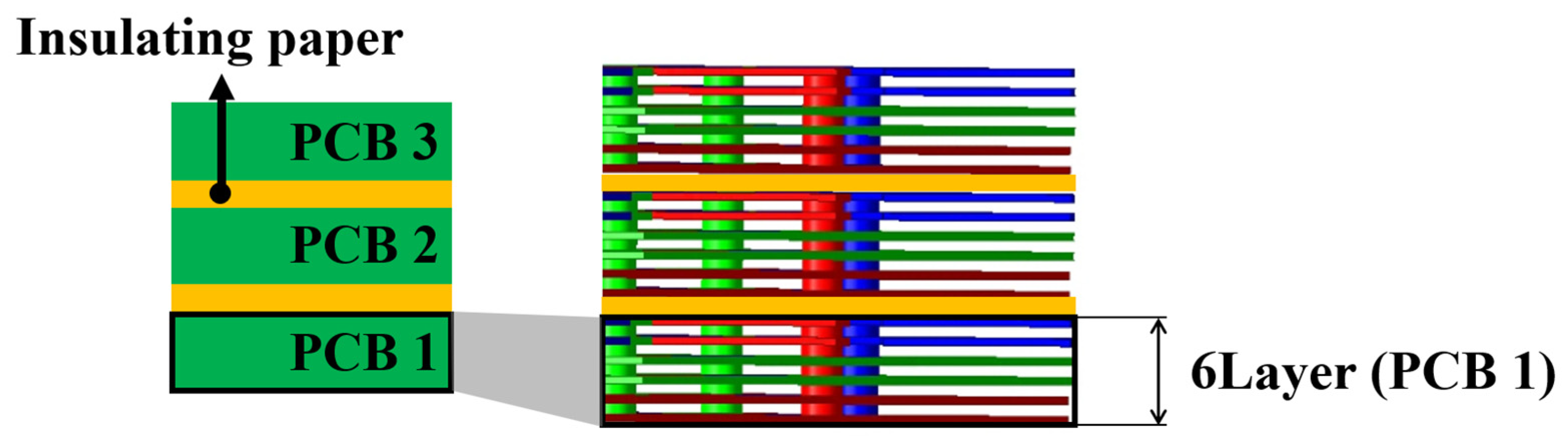

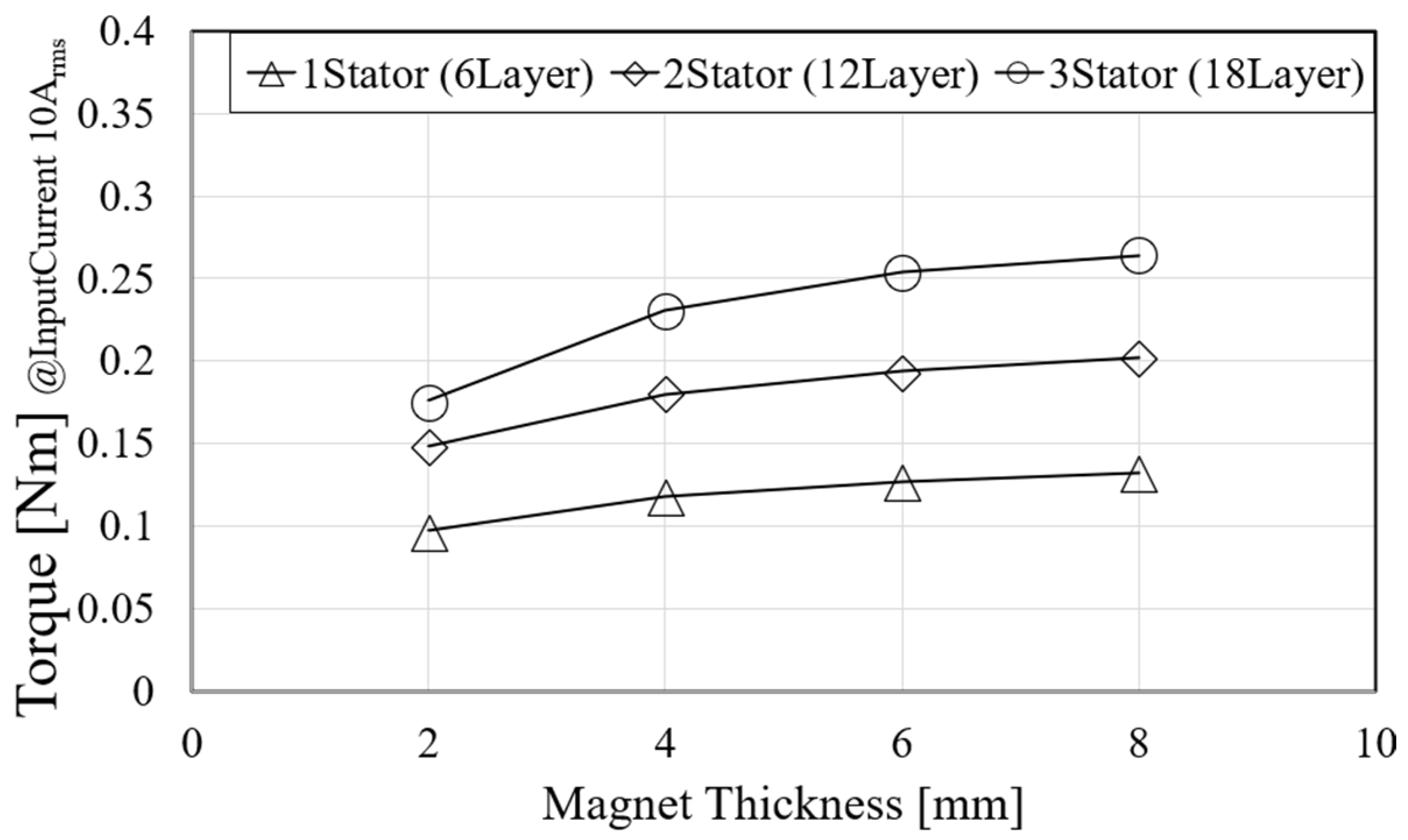

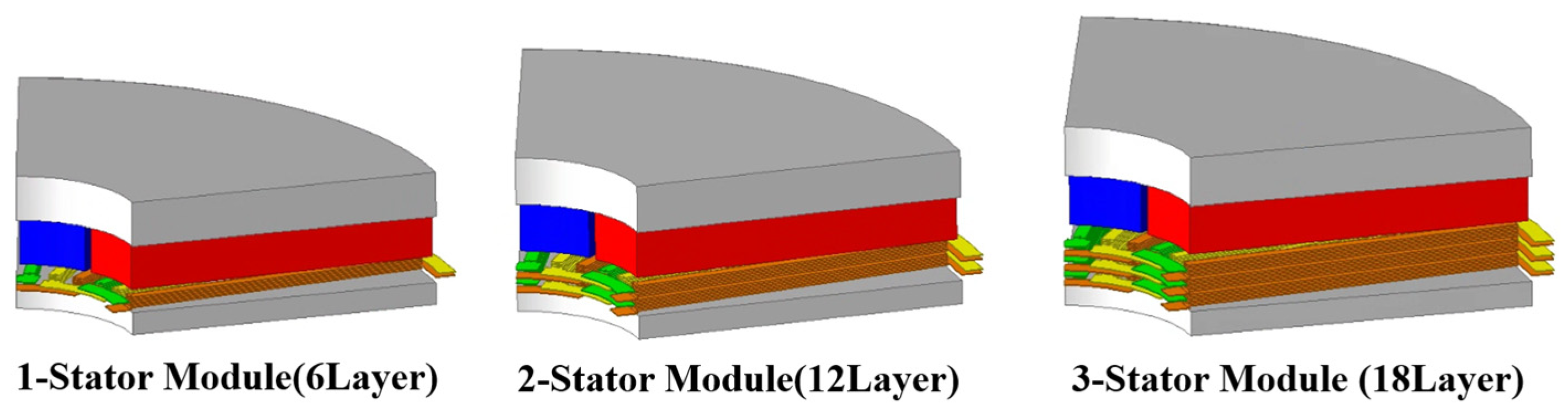

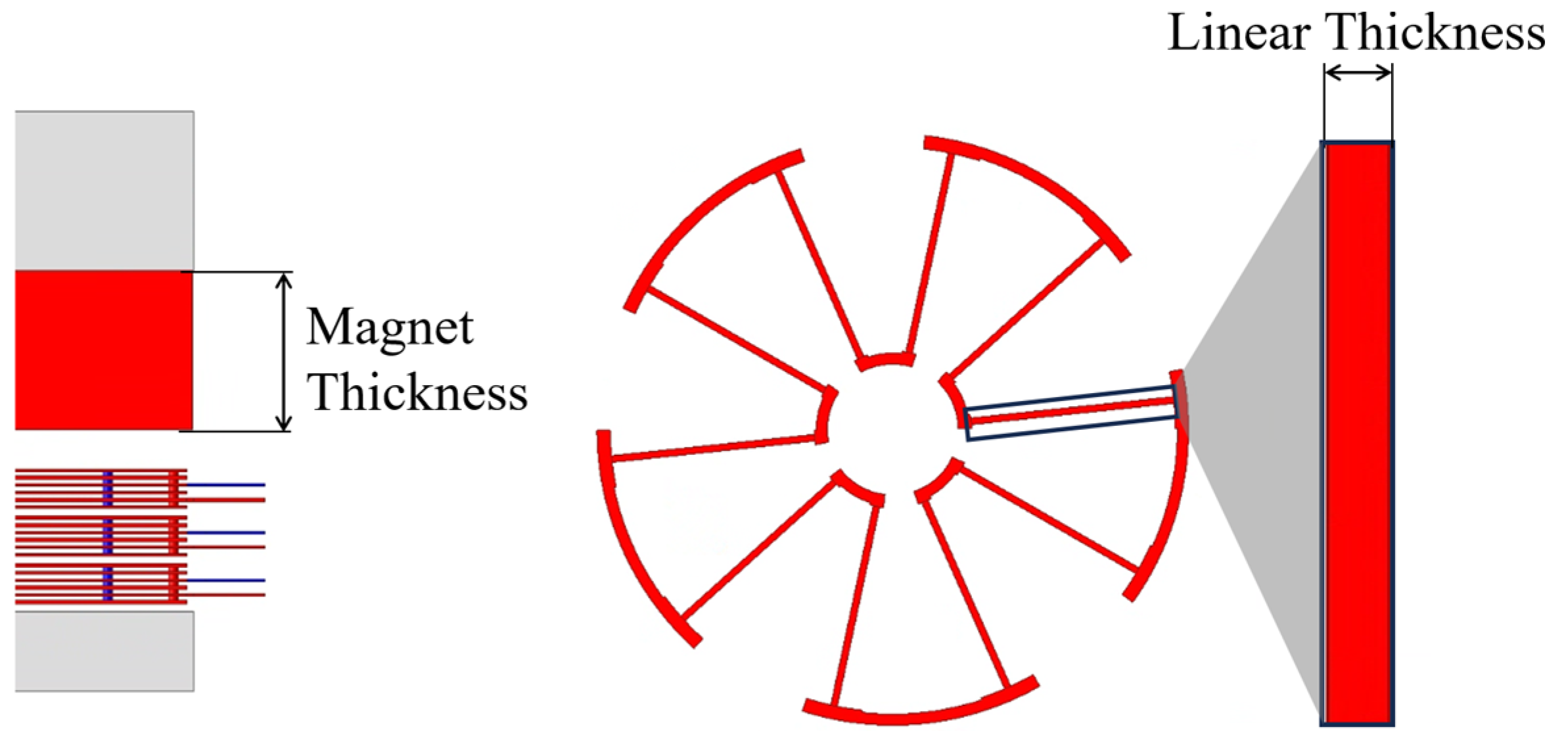

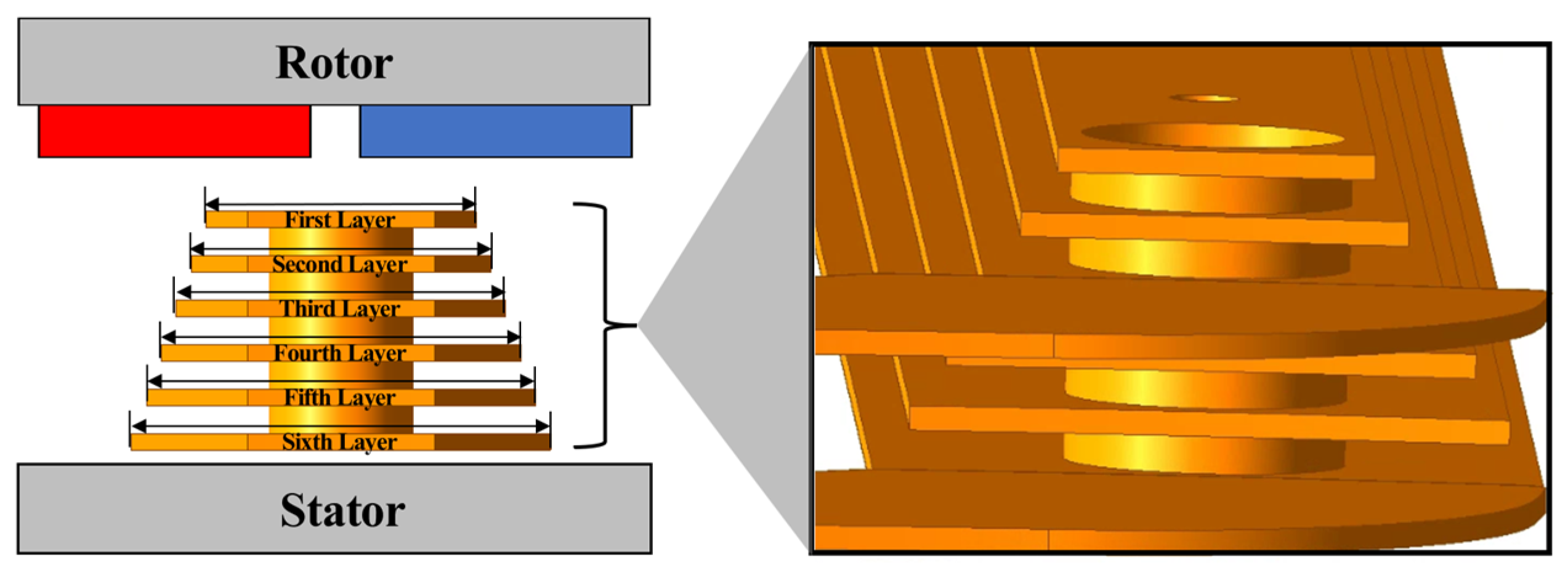

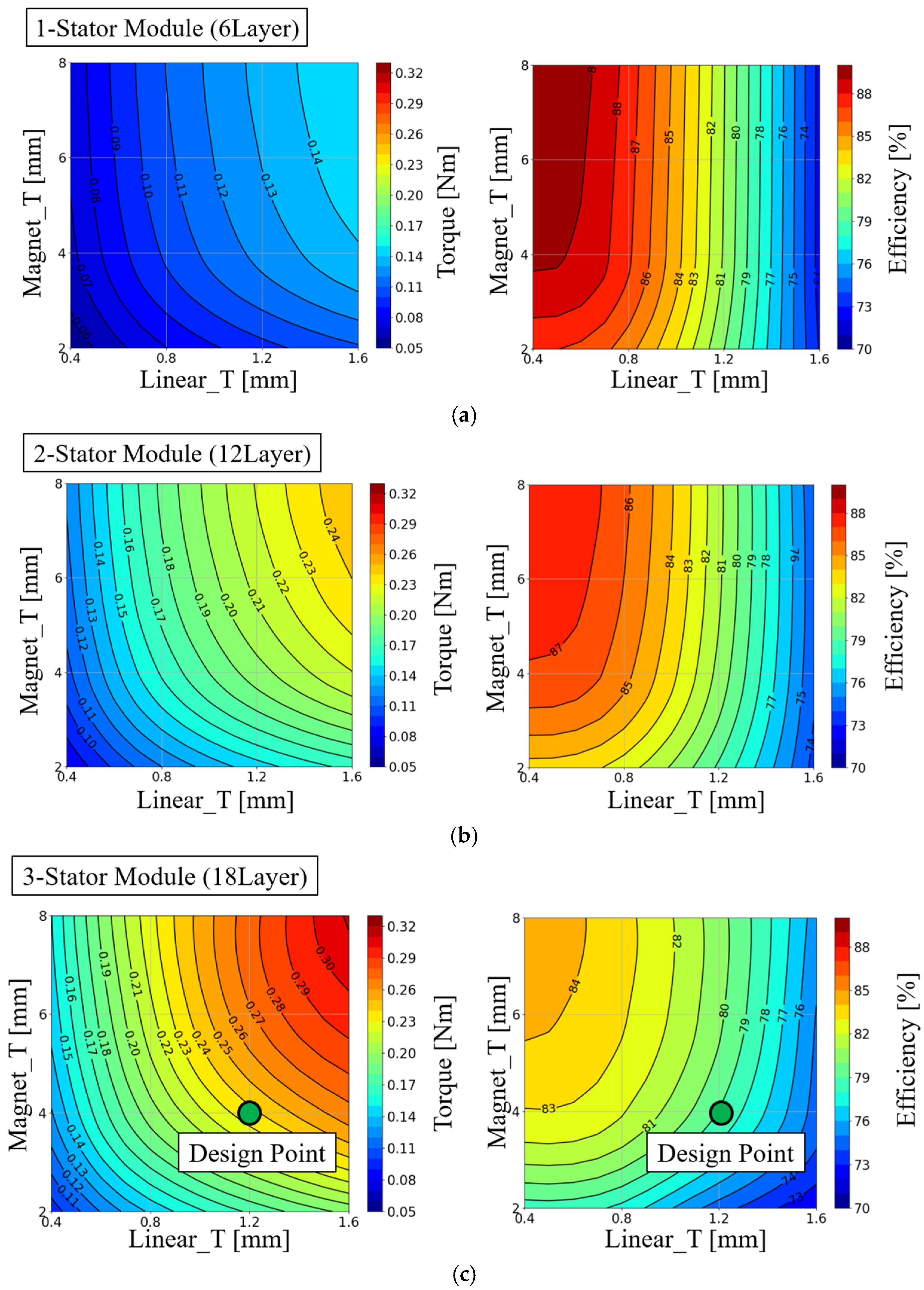

3.1. Description and Specifications of the Basic 3D FEA Model According to the Number of Stator Modules

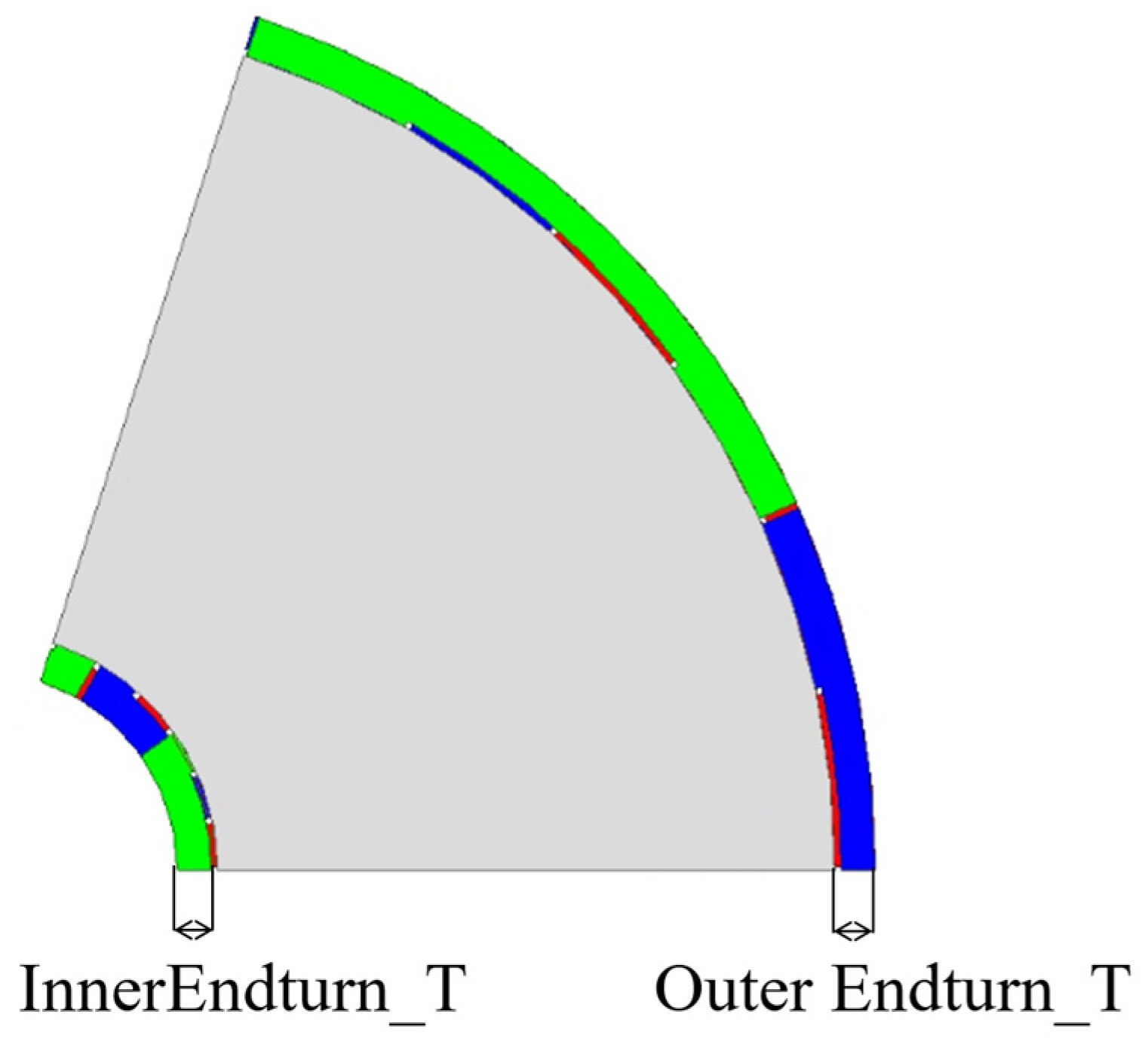

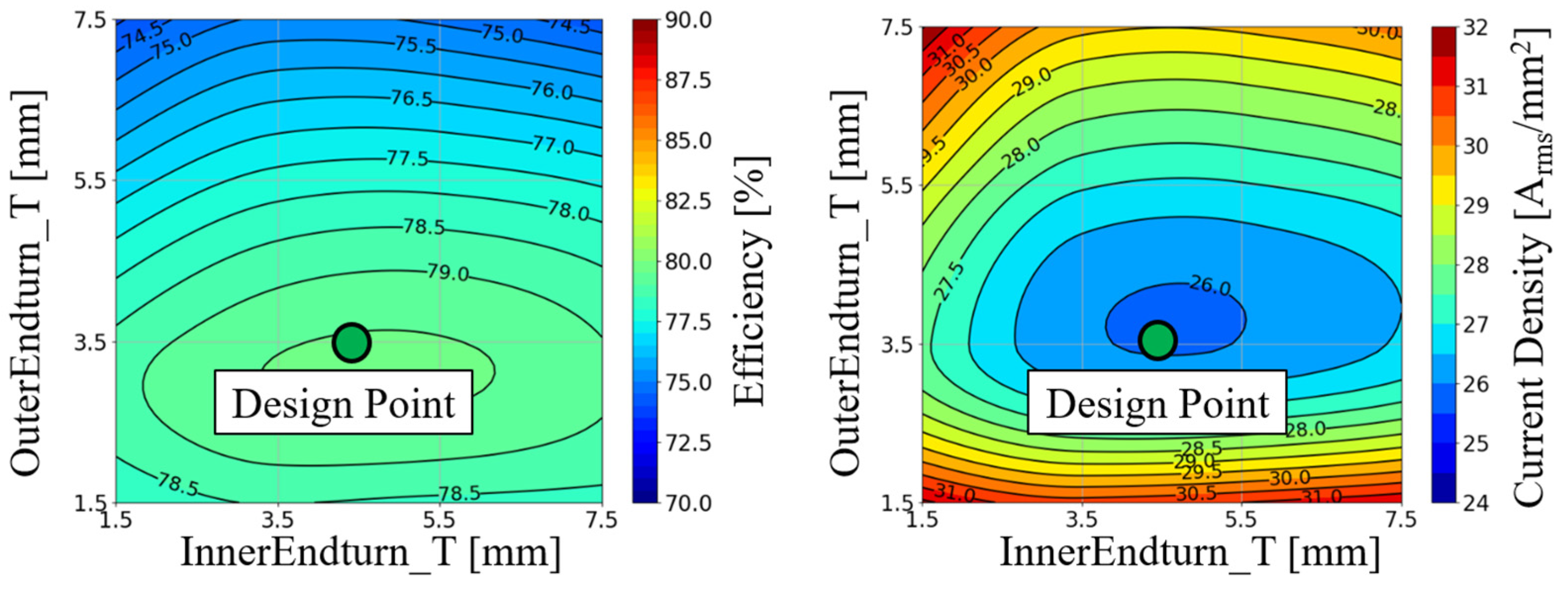

3.2. End-Turn Optimization Design of the 3D FEA Model

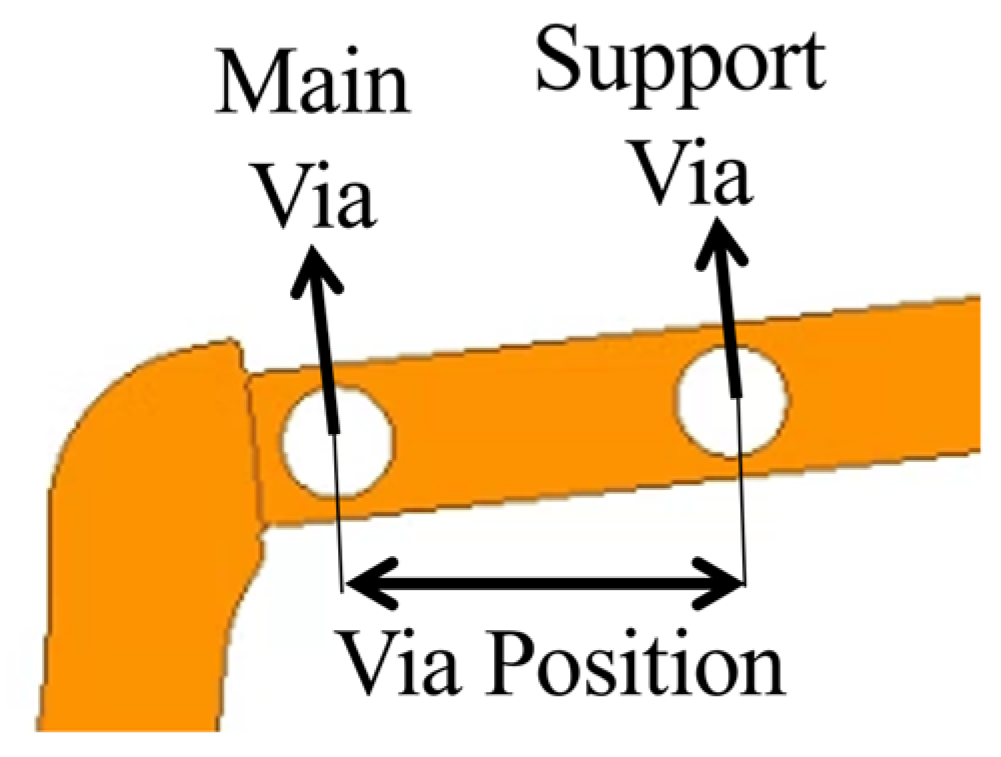

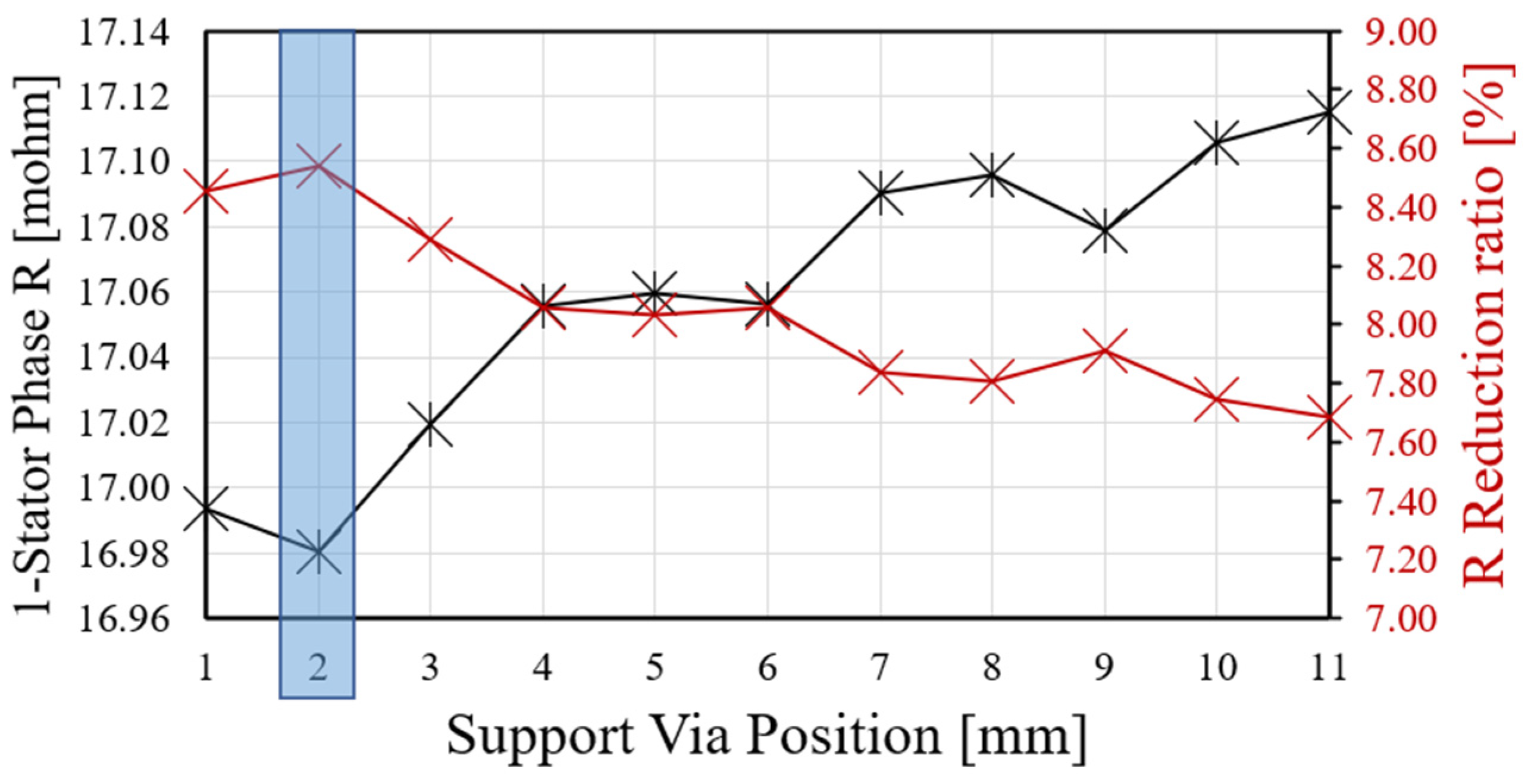

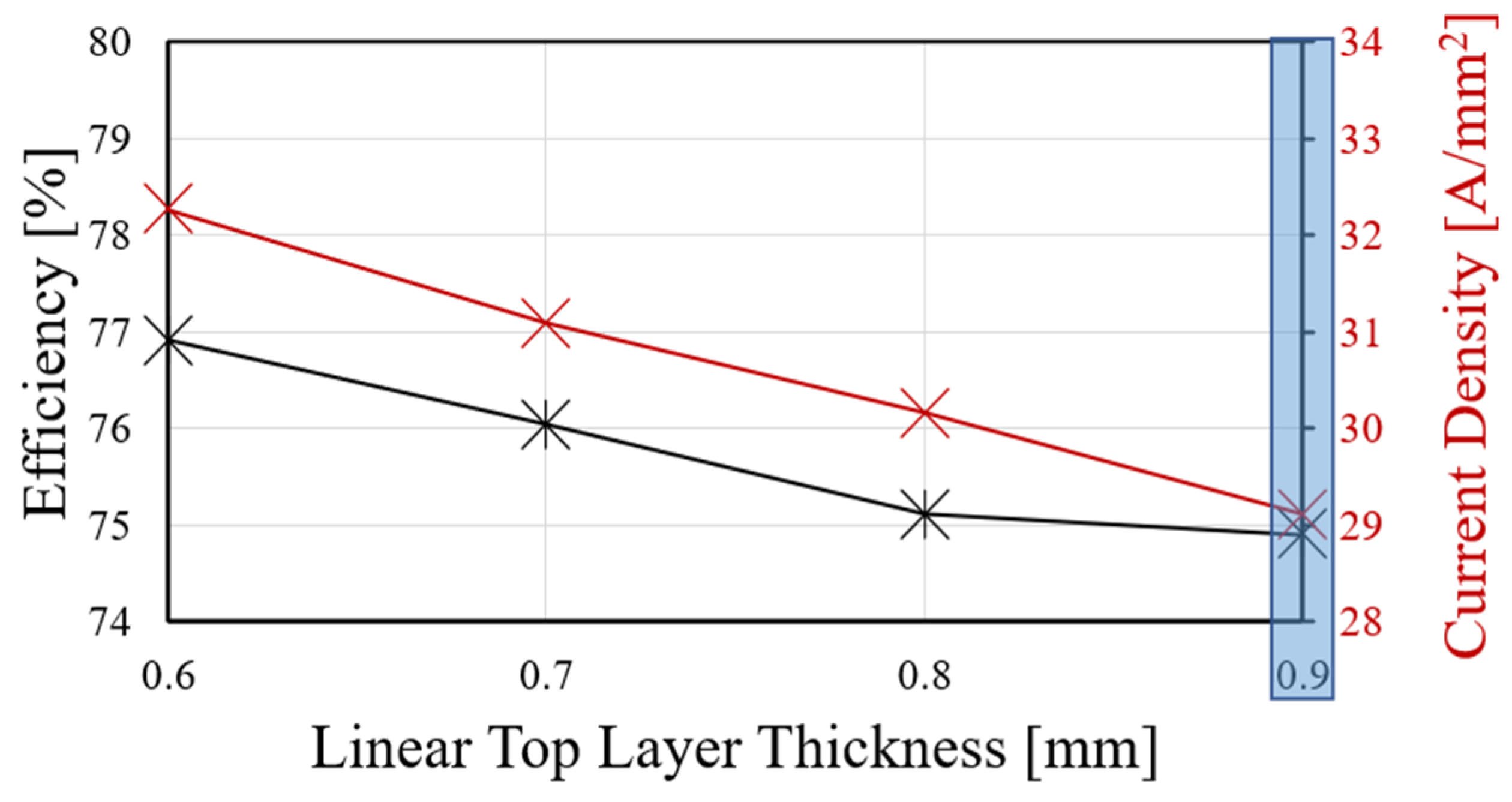

3.3. Via Design and Pyramid Trace of the 3D FEA Model for Loss Reduction

4. Derivation of the Final 3D FEA Model, Proto-Type Test and Validation

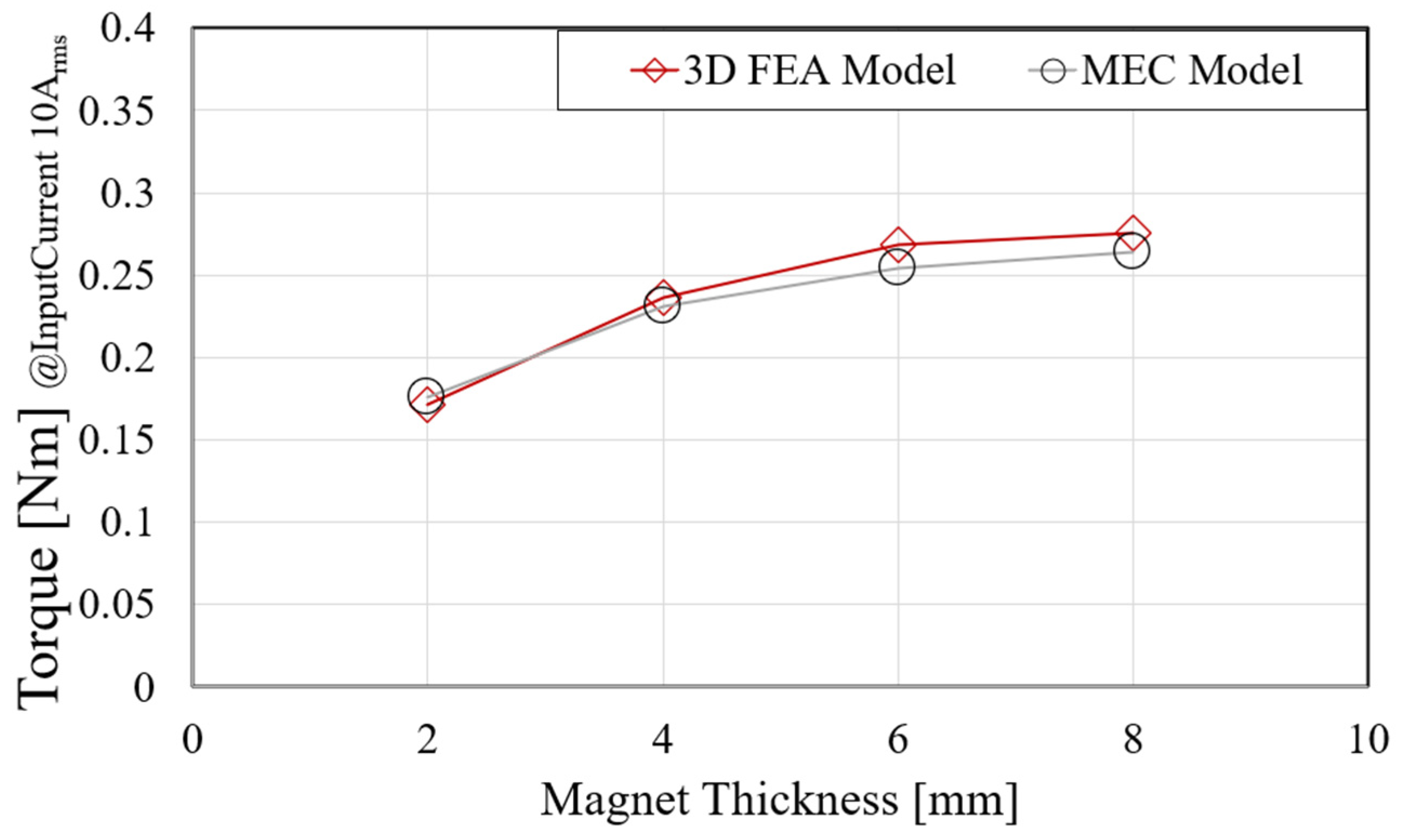

4.1. Derivation Process of the Final 3D FEA Model and Data Comparison with the MEC Model

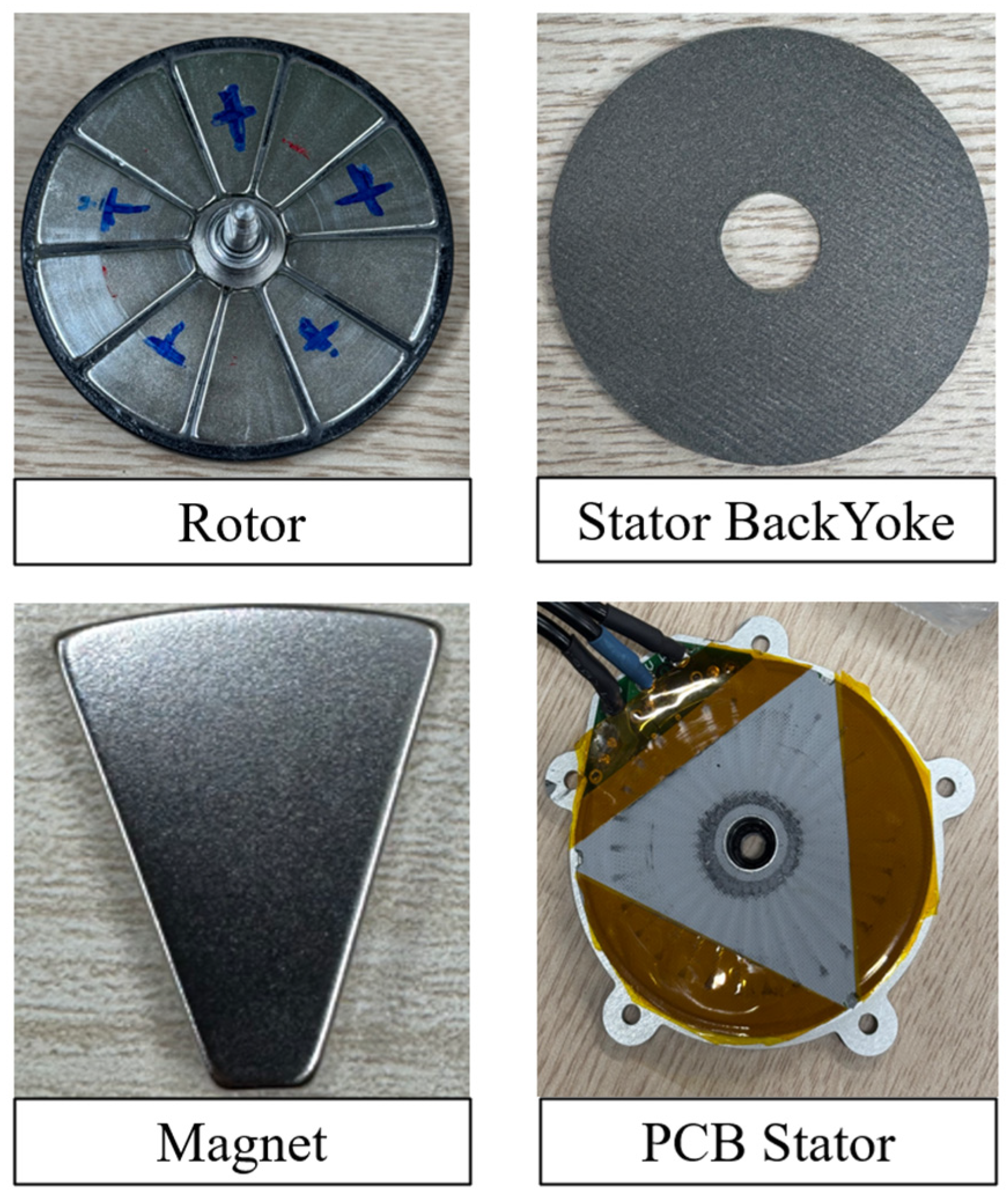

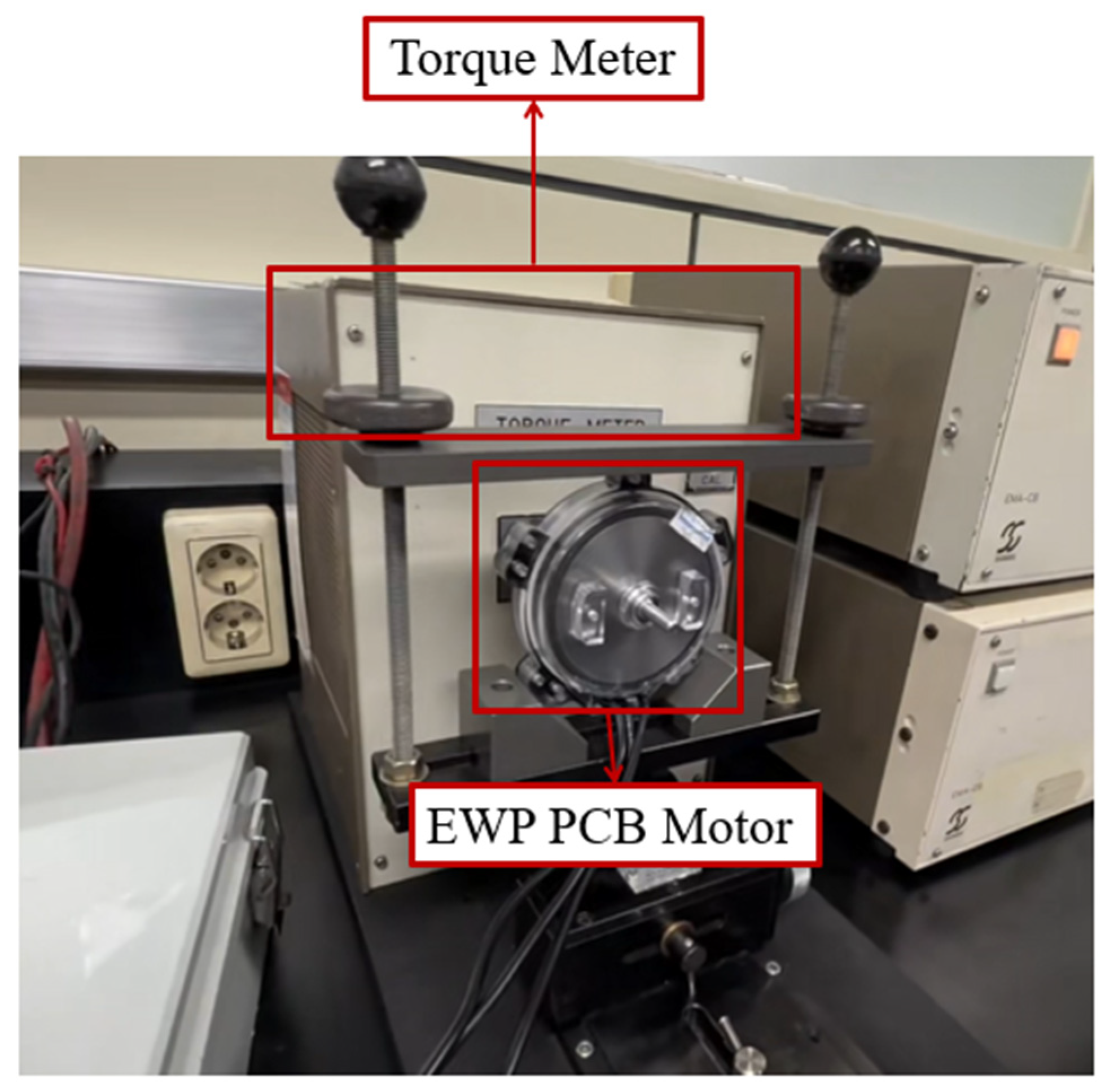

4.2. Photographs of the Prototype and Test Environment

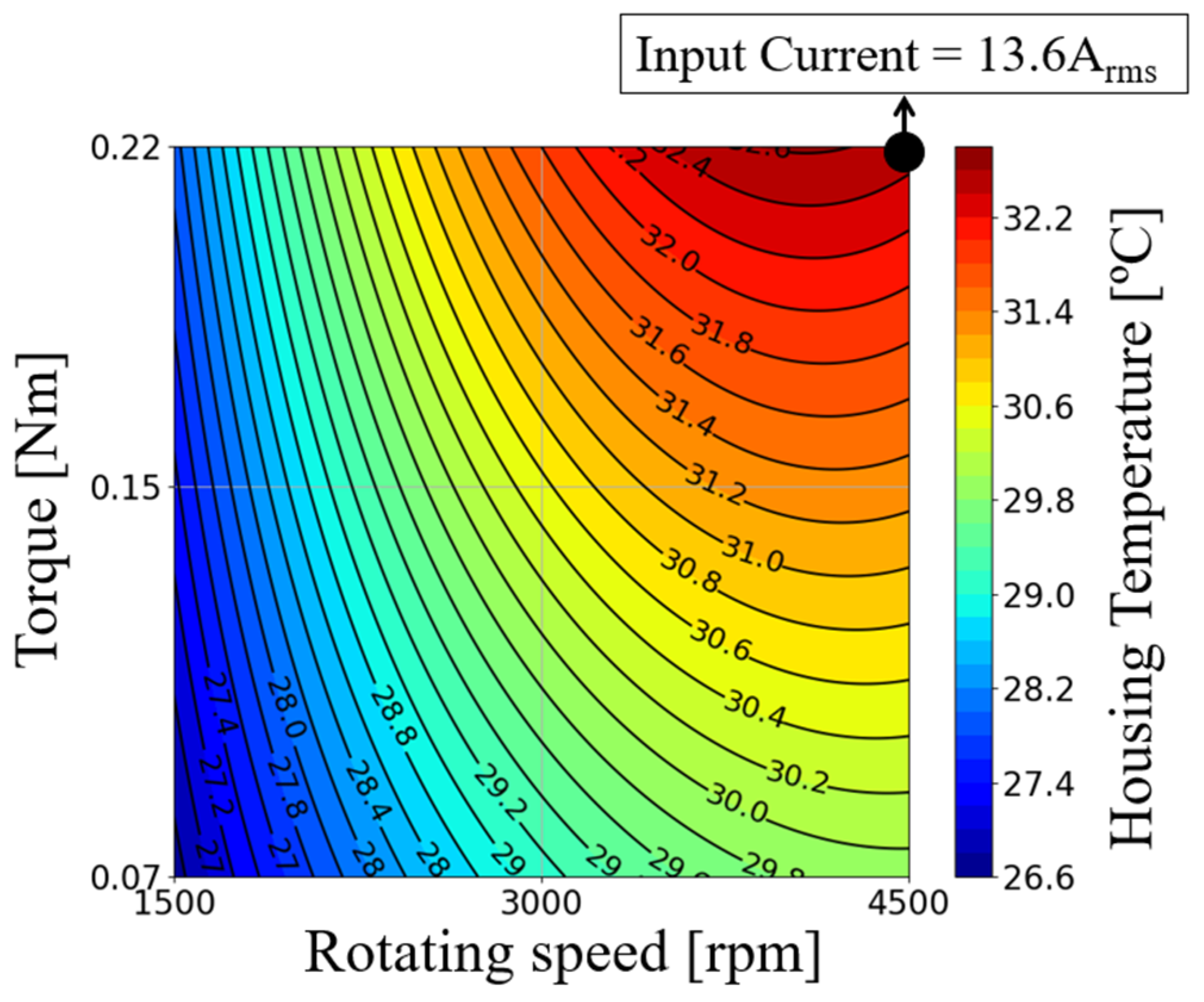

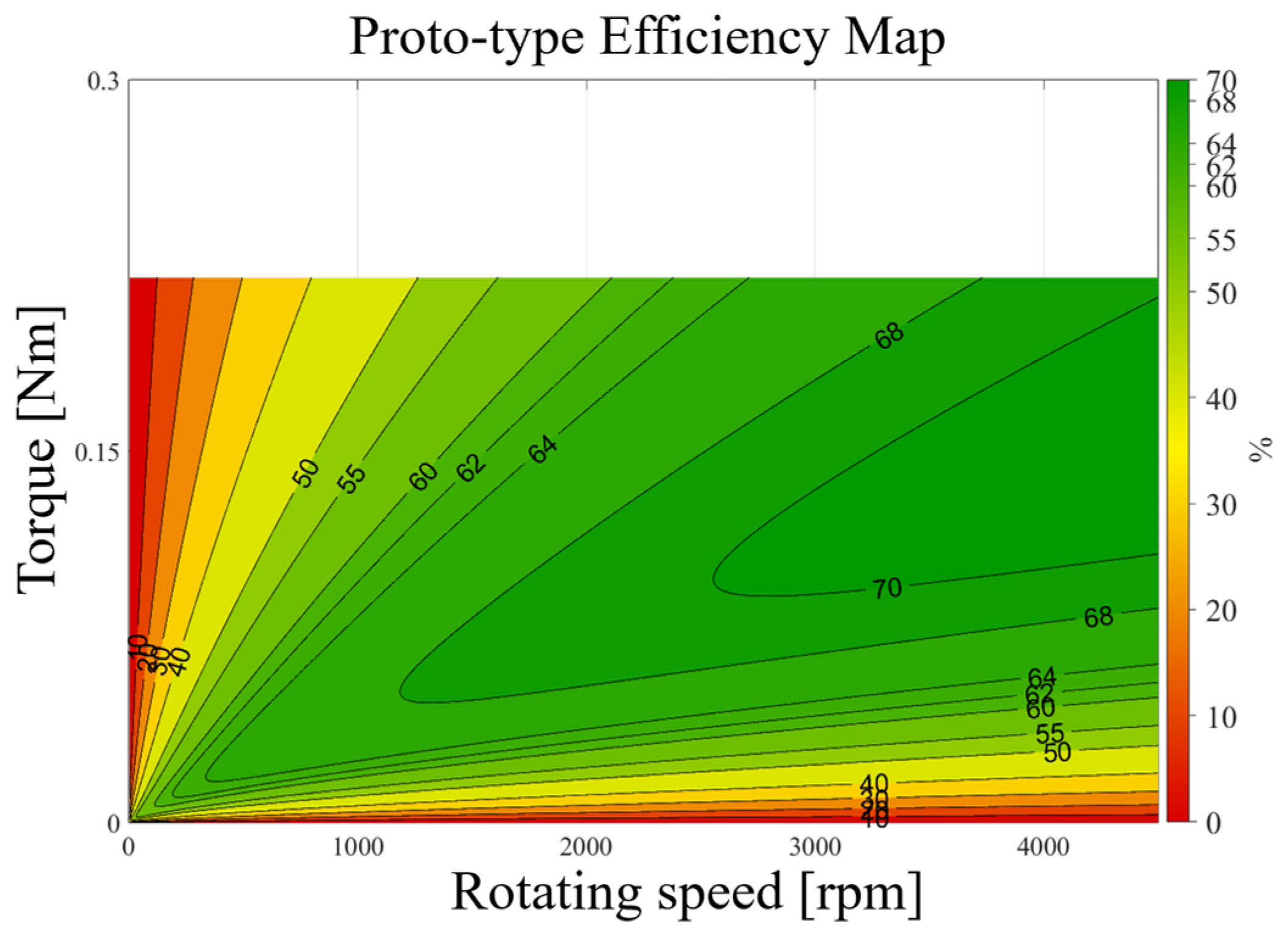

4.3. Prototype Test Results and Comparison

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.; Wen, M.; Yang, H.; Yue, Z.; Yao, M. A Review of Thermal Management System and Control Strategy for Automotive Engines. J. Energy Eng. 2021, 147, 03121001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Jung, D.; Filipi, Z.S.; Assanis, D.N.; Vanderslice, J.; Bryzik, W. Application of Controllable Electric Coolant Pump for Fuel Economy and Cooling Performance Improvement. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2007, 129, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighat, A.; Roumi, S.; Madani, N.; Bahmanpour, D.; Olsen, M.G. An Intelligent Cooling System and Control Model for Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 128, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, M.H.; Mitchell, T.H.; Wagner, J.R.; Dawson, D.M. A Smart Multiple-Loop Automotive Cooling System—Model, Control, and Experimental Study. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2010, 15, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taqavi, O.; Mirimani, S.M. Design Aspects, Winding Arrangements and Applications of Printed Circuit Board Motors: A Comprehensive Review. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2020, 14, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahfock, A.; Gambetta, D. Sensorless Commutation of Printed Circuit Brushless Direct Current Motors. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2010, 4, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethu, S.; Nikam, S.P.; Singh, S.; Pal, S.; Wankhede, A.K.; Fernandes, B.G. High-Speed Coreless Axial-Flux Permanent-Magnet Motor With Printed Circuit Board Winding. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Marignetti, F.; Volpe, G.; Mirimani, S.; Cecati, C. Electromagnetic Design and Modeling of a Two-Phase Axial-Flux Printed Circuit Board Motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, N.; Nikam, S.P.; Pal, S.; Wankhede, A.K.; Fernandes, B.G. Multiphysics Analysis of Printed Circuit Board Winding for High-Speed Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Motor. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2019, 13, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulaee, Y.; Lewis, D.D.; Mohammadi, A.; Heins, G.; Patterson, D.; Ionel, D.M. Circulating and Eddy Current Losses in Coreless Axial Flux PM Machine Stators With PCB Windings. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 4010–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, G.; Dehez, B. Impact of Slit Configuration on Eddy Current and Supply Current Losses in PCB Winding of Slotless PM Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 6035–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokgöz, F.; Çakal, G.; Keysan, O. Comparison of PCB Winding Topologies for Axial-Flux Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2020, 14, 2577–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, H.; Li, X. Winding Design and Analysis for a Disc-Type Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motor with a PCB Stator. Energies 2018, 11, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.A. Improved Analytical Modeling of Conductive Losses in Magnetic Components. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1994, 9, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, O.; Popiel, L.; Pages, J.-L. Proximity Losses Computation with a 2D Complex Permeability Modelling. In IEEE Transactions on Magnetics; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dowell, P.L. Effects of Eddy Currents in Transformer Windings. In Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, London, UK, 1 August 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.-Y.; Pang, W.; Gao, P.; Zhao, X. Electromagnetic Design and Analysis of Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Generator with Unequal-Width PCB Winding. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 164696–164707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.-B.; Choi, D.-H.; Han, H.-S.; Song, Y.-H.; Kim, W.-H. A Study on Reducing Loss in PCB Motor Stator Using Multi-Via Structure. Actuators 2025, 14, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadiyar, N.; Van Verdeghem, J.; Severson, E.L. A Review of Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Machine Technology. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 4, 3920–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviainen, A.; Niemela, M.; Pyrhonen, J. Modeling of Axial Flux Permanent-Magnet Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2004, 40, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojaghlu, P.; Vahedi, A.; Totoonchian, F. Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Modelling of Ring Winding Axial Flux Machine. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2018, 12, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yang, X.; Wei, G.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Qin, M.; Wu, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, W.; Wang, L. A Novel Pyramid Winding for PCB Planar Inductors with Fewer Copper Layers and Lower AC Copper Loss. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 11461–11468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Pole/Slot | 10/30 | - |

| PCB Stator Inner Diameter | 80 | mm |

| PCB Stator Outer Diameter | 17.7 | mm |

| Stack length (Active) | 14.4 | mm |

| Trace Copper Thickness | 2 | oz |

| Trace Layer (Parallel) | 6 | - |

| Core | 35PN300 | - |

| Magnet | N45UH | - |

| PCB Prepreg | FR-4 | - |

| Coil | Copper | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choi, D.-H.; Kim, W.-H.; Jang, H. Magnetic Equivalent Circuit-Based Performance Evaluation of Modular PCB AFPM Motor for Electric Water Pumps. Actuators 2026, 15, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020087

Choi D-H, Kim W-H, Jang H. Magnetic Equivalent Circuit-Based Performance Evaluation of Modular PCB AFPM Motor for Electric Water Pumps. Actuators. 2026; 15(2):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020087

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Do-Hyeon, Won-Ho Kim, and Hyungkwan Jang. 2026. "Magnetic Equivalent Circuit-Based Performance Evaluation of Modular PCB AFPM Motor for Electric Water Pumps" Actuators 15, no. 2: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020087

APA StyleChoi, D.-H., Kim, W.-H., & Jang, H. (2026). Magnetic Equivalent Circuit-Based Performance Evaluation of Modular PCB AFPM Motor for Electric Water Pumps. Actuators, 15(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020087