Design and Investigation of Powertrain with In-Wheel Motor for Permanent Magnet Electrodynamic Suspension Maglev Car

Abstract

1. Introduction

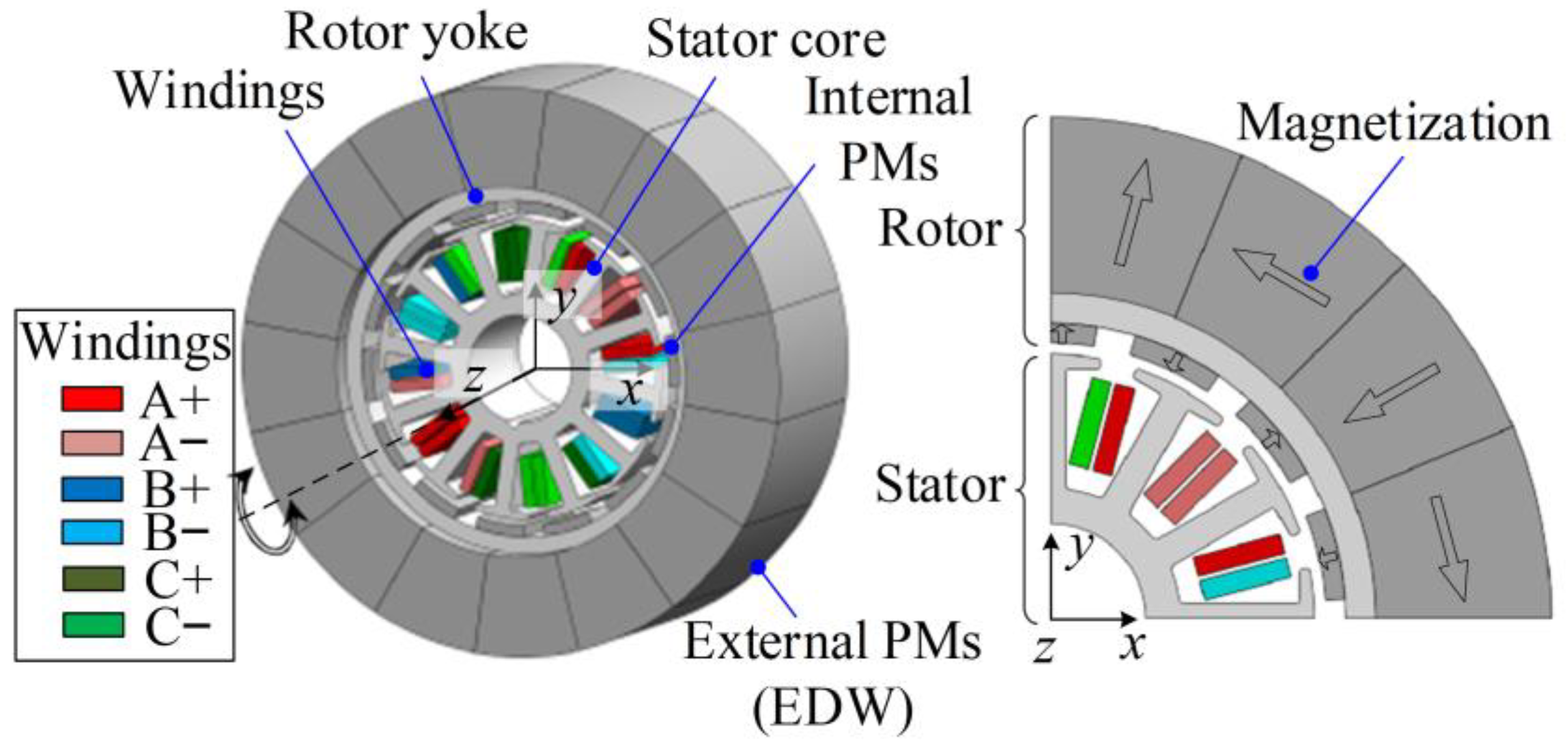

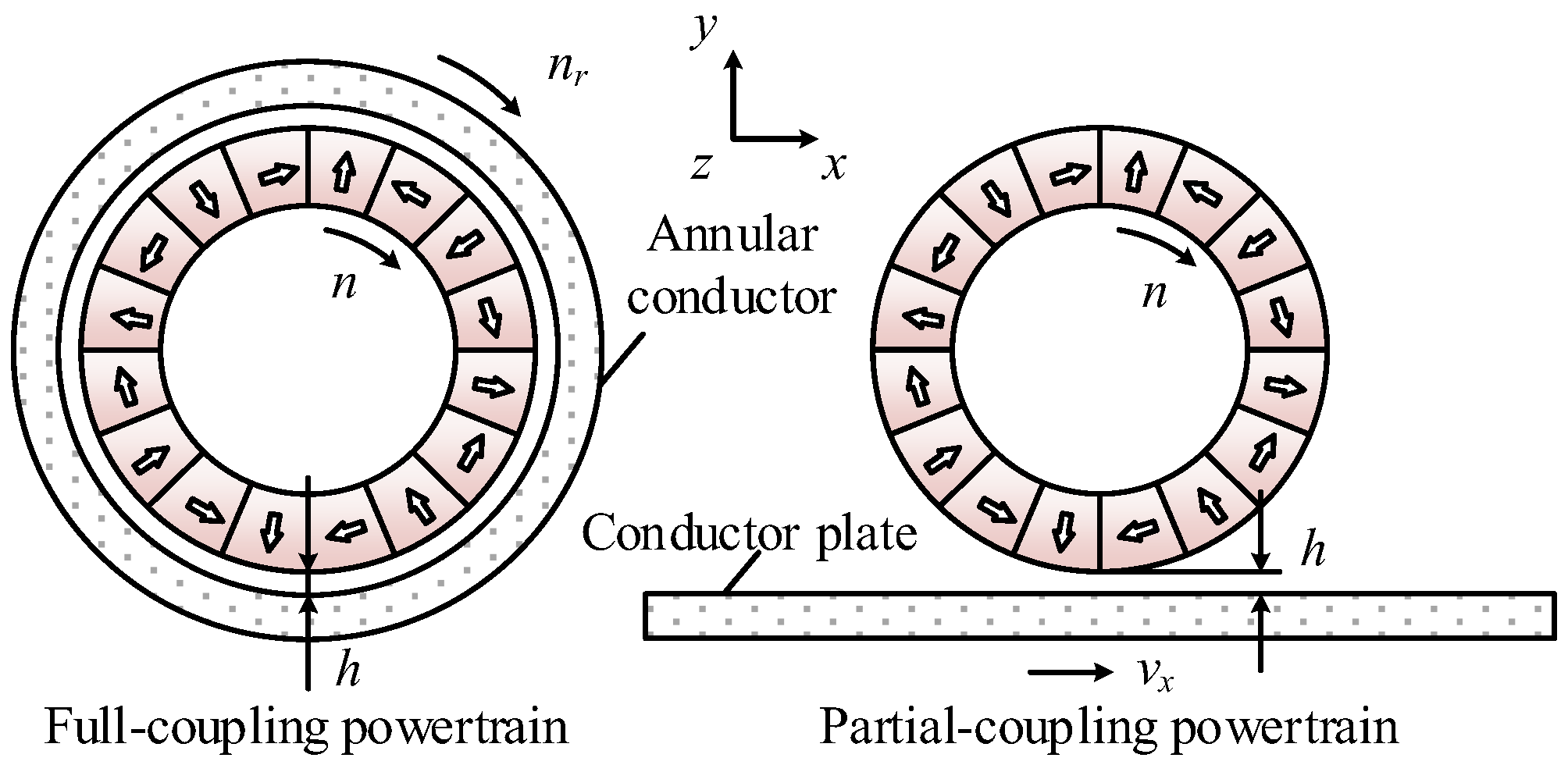

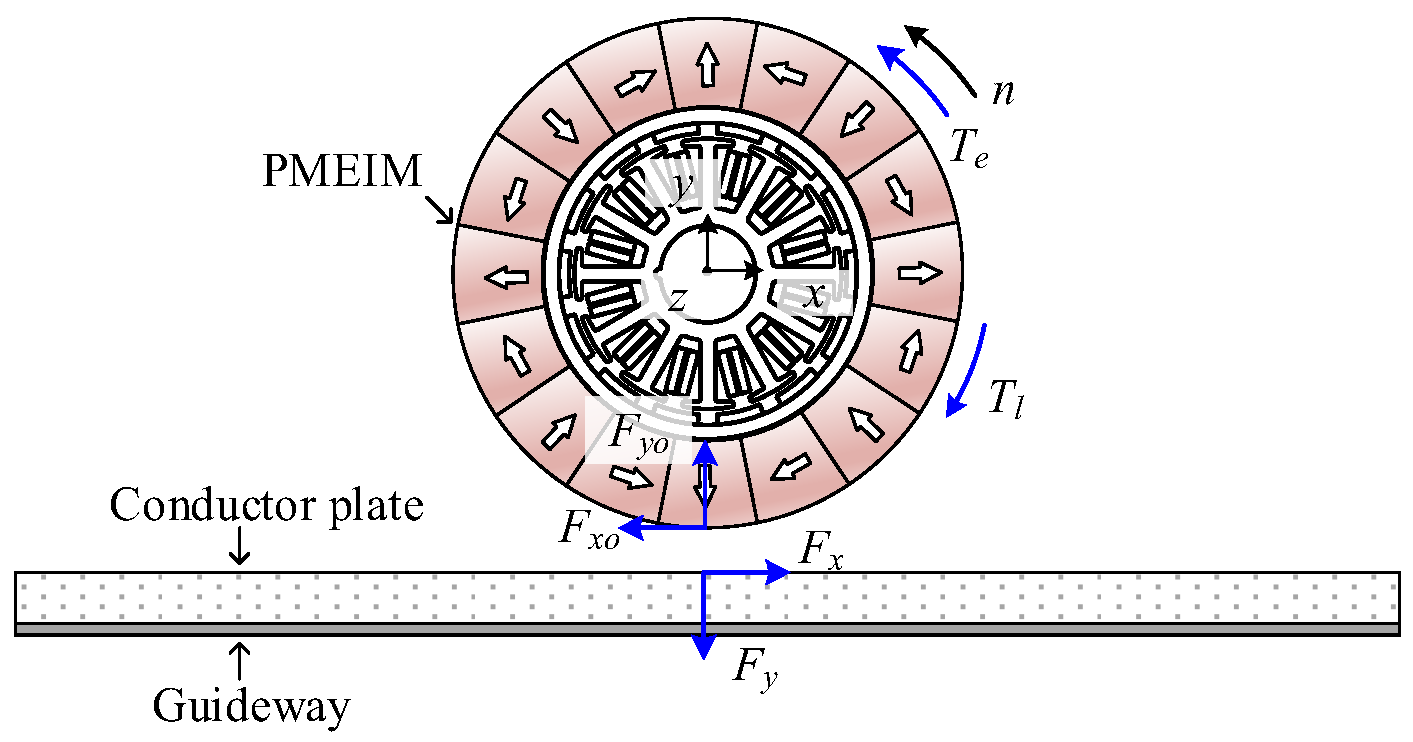

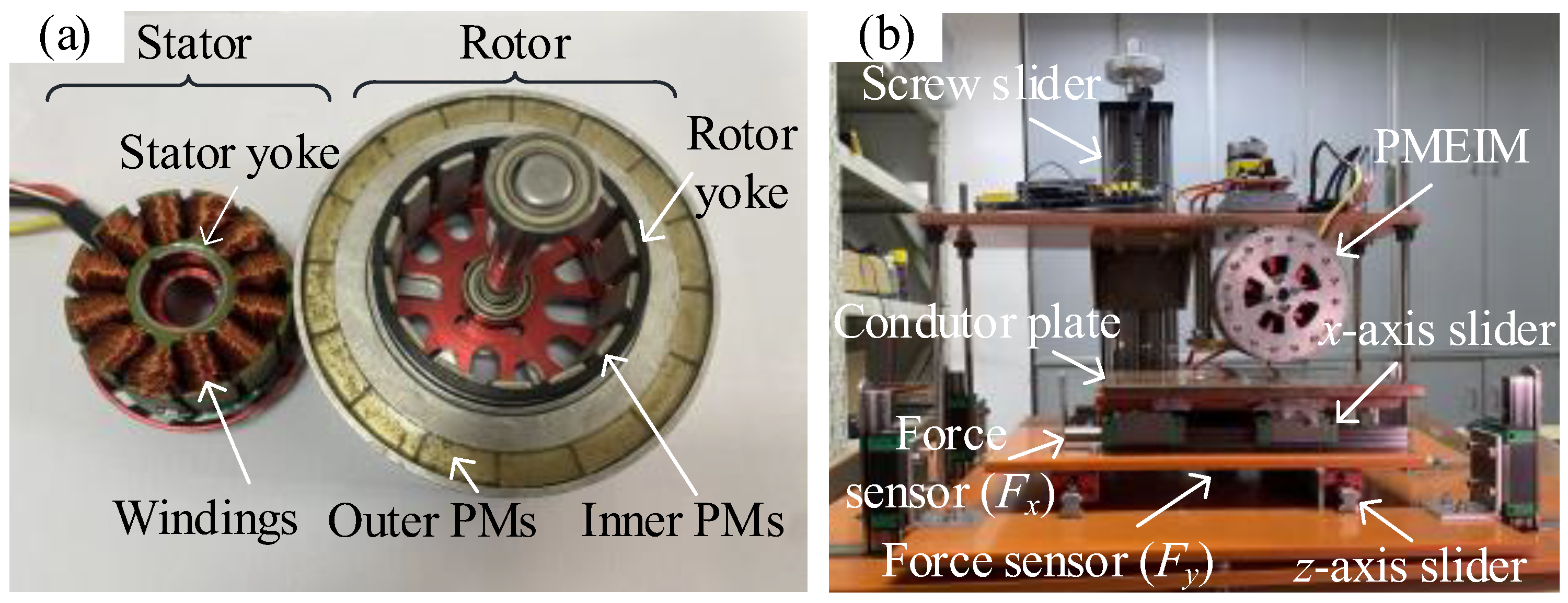

2. Description of PMEIM

- (i)

- Static levitation: Front and rear wheels rotate in opposite directions at the same speed, where tangential forces cancel each other out while normal forces superimpose to enable static vehicle levitation.

- (ii)

- Propulsion and braking: Front and rear wheels rotate at different speeds, where the resulting speed difference generates a net tangential force for vehicle propulsion or braking, with normal forces remaining superimposed.

- (iii)

- Steering: The speed difference between left and right wheels produces differential tangential forces, creating a yaw moment to facilitate vehicle steering.

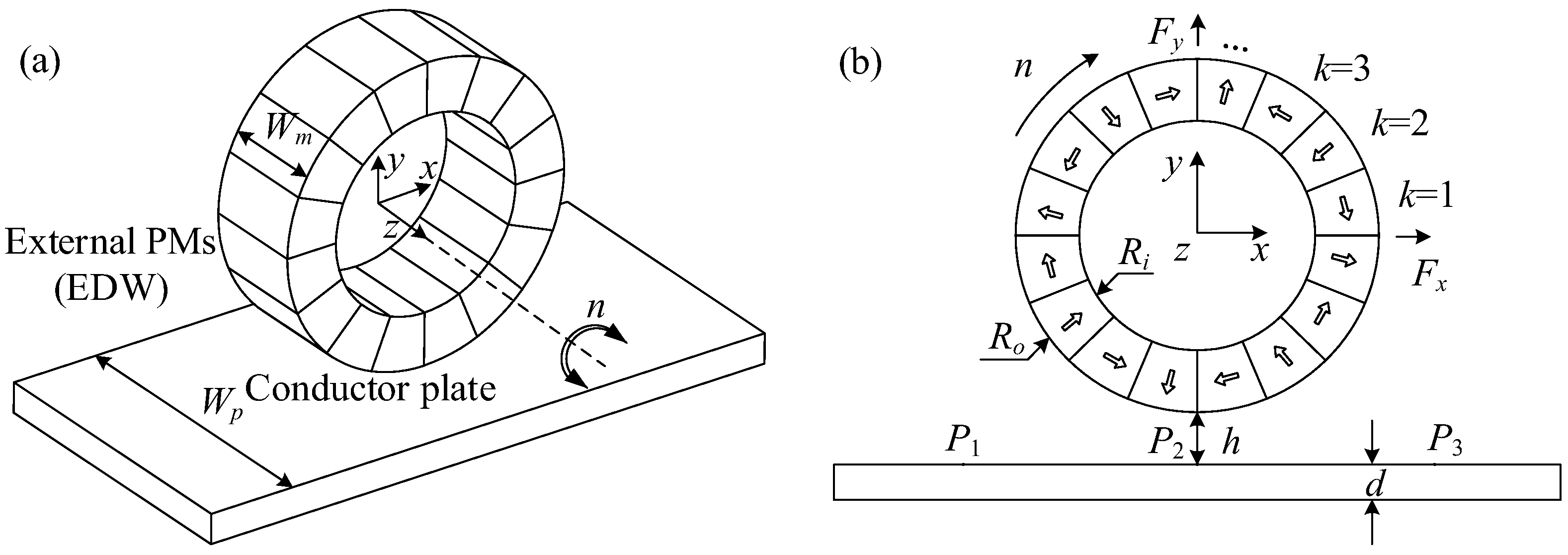

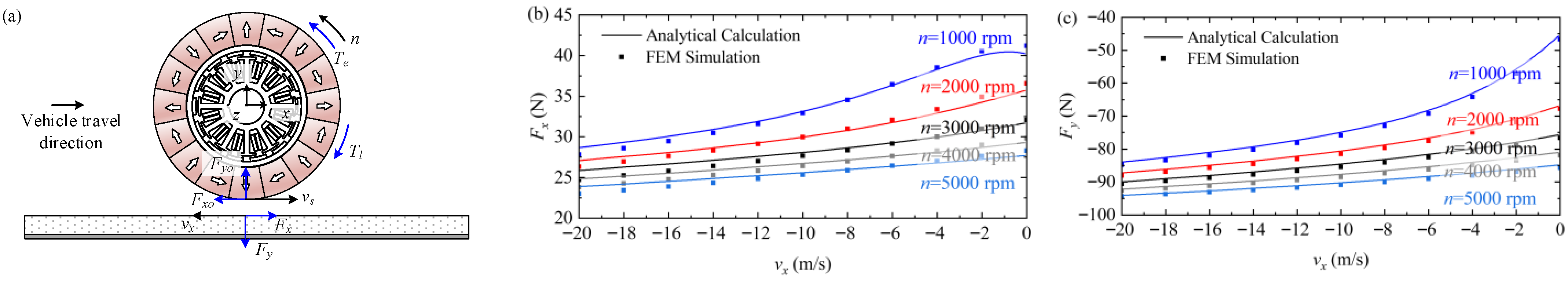

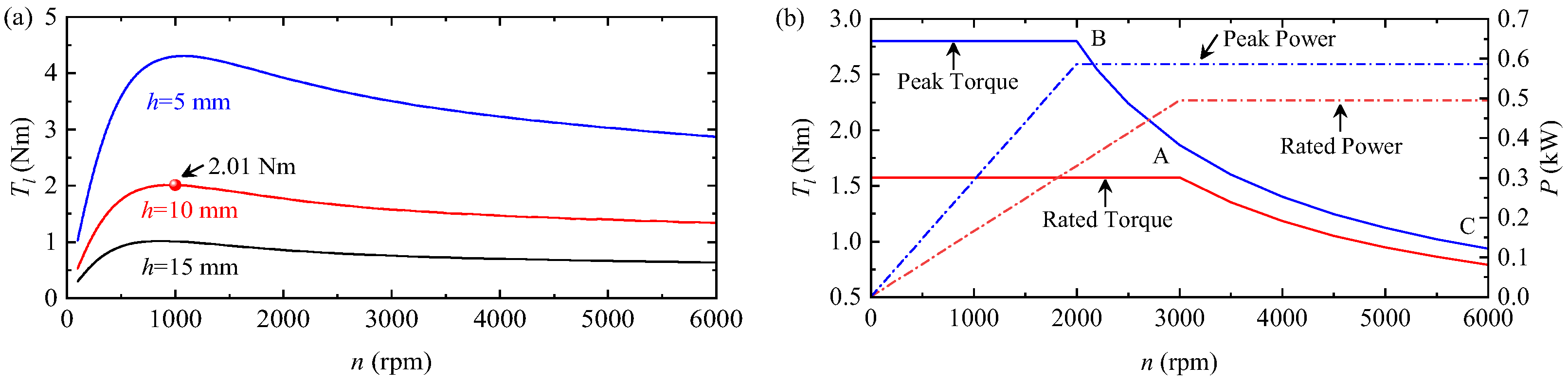

3. Mechanical Characteristic of PMEIM Powertrain

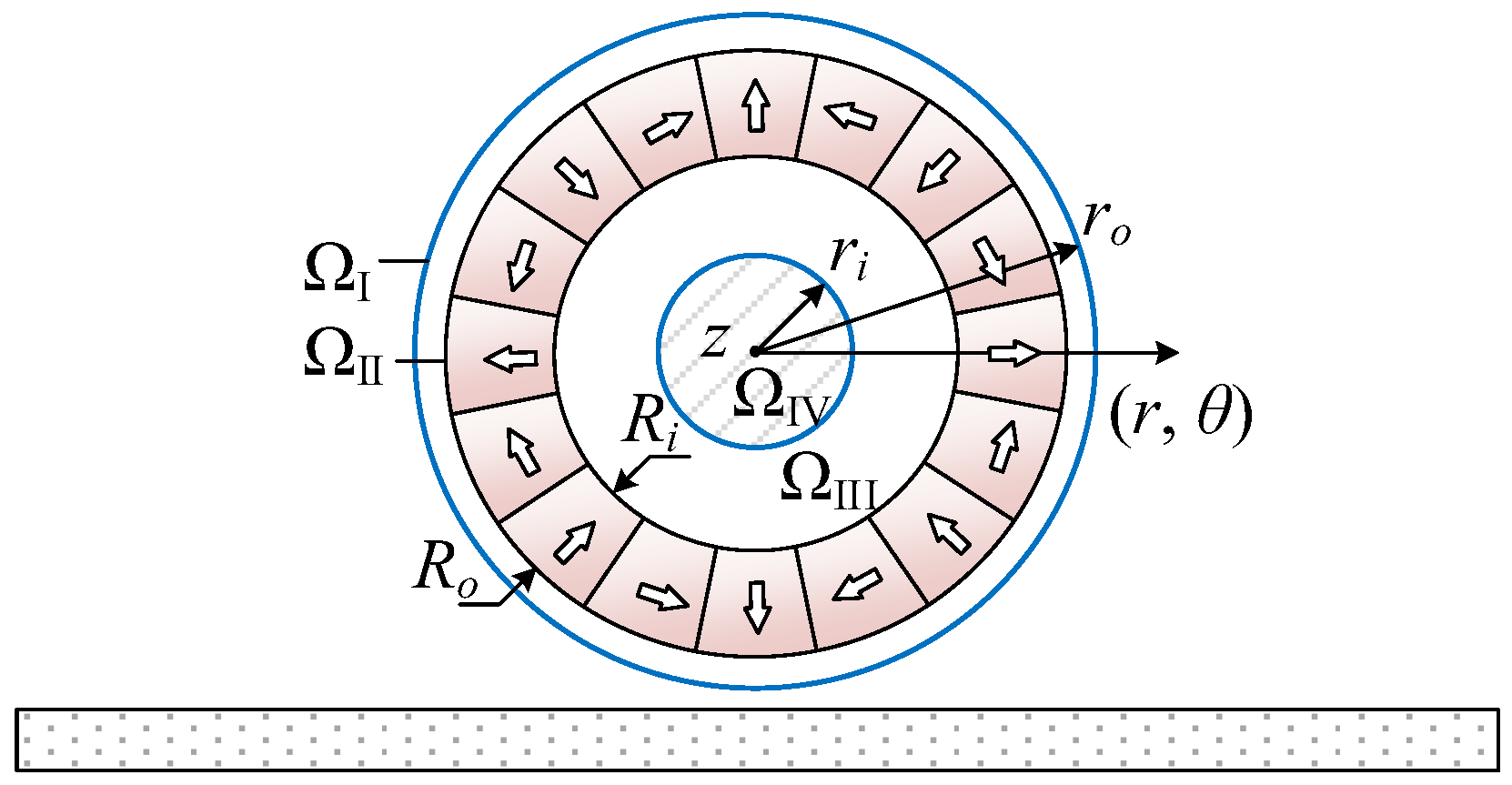

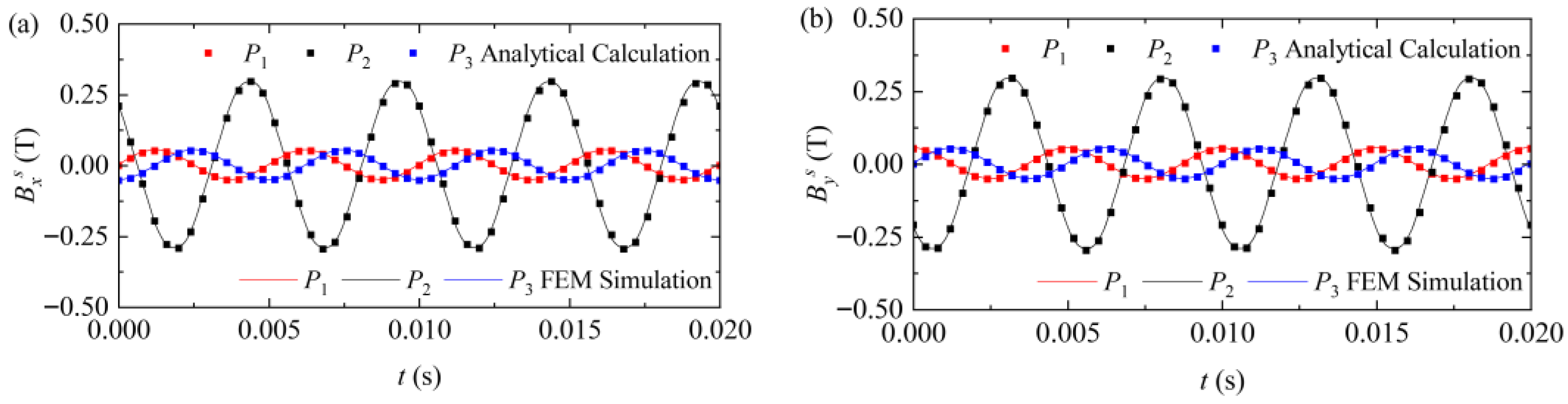

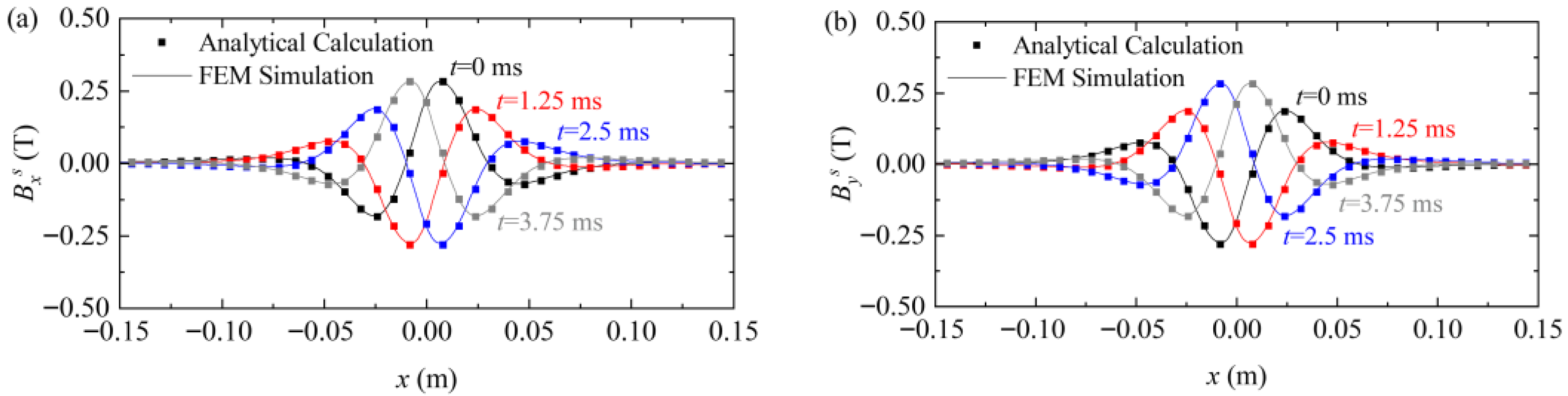

3.1. Magnetic Field

- (i)

- A cylindrical coordinate system r-θ-z is established at the geometric center of the PMEIM.

- (ii)

- The z-axis is infinitely long, and the magnetic flux density is uniformly distributed along the z-axis, without attenuation due to the transverse end effect.

- (iii)

- The magnetic yoke is infinitely permeable.

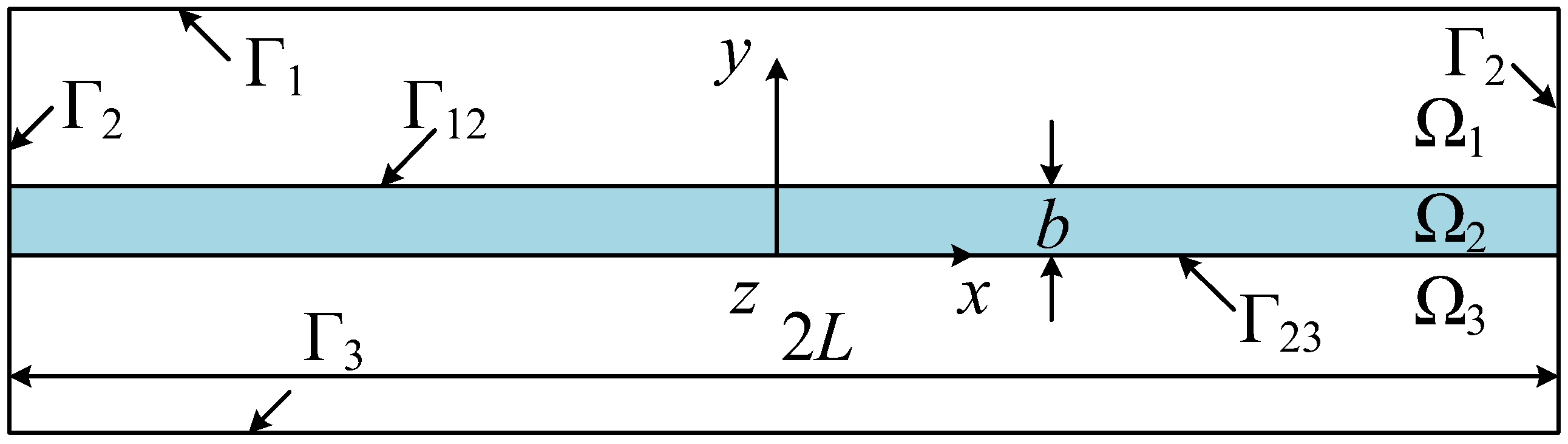

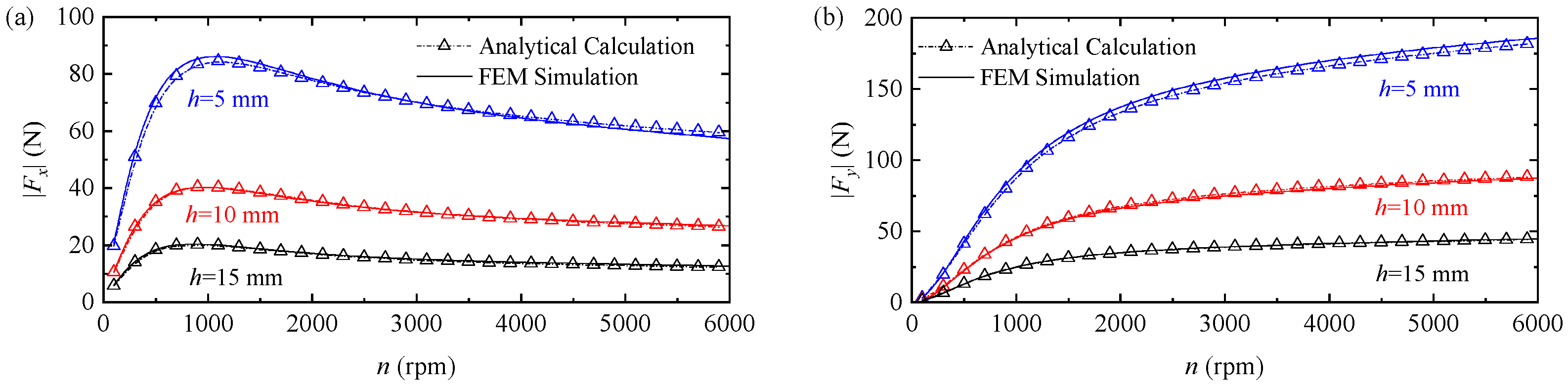

3.2. Electromagnetic Force

- (i)

- A Cartesian coordinate system x-y-z is established, with its origin at the geometric center of the conductor plate’s lower surface.

- (ii)

- The magnetic flux density is uniformly distributed axially, free from attenuation due to the transverse end effect.

- (iii)

- The conductor plate is isotropic and homogeneous, with its dimensions greatly exceeding the coverage range of the source magnetic field.

3.3. Operating State

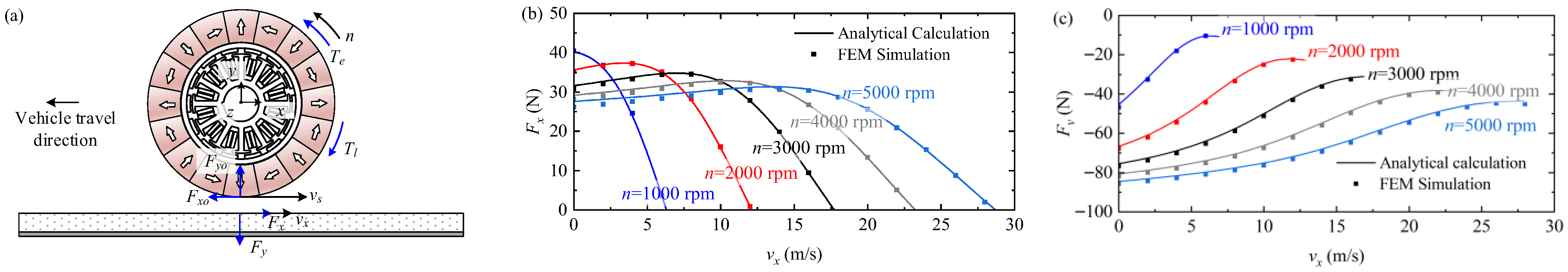

3.3.1. Motor Operation

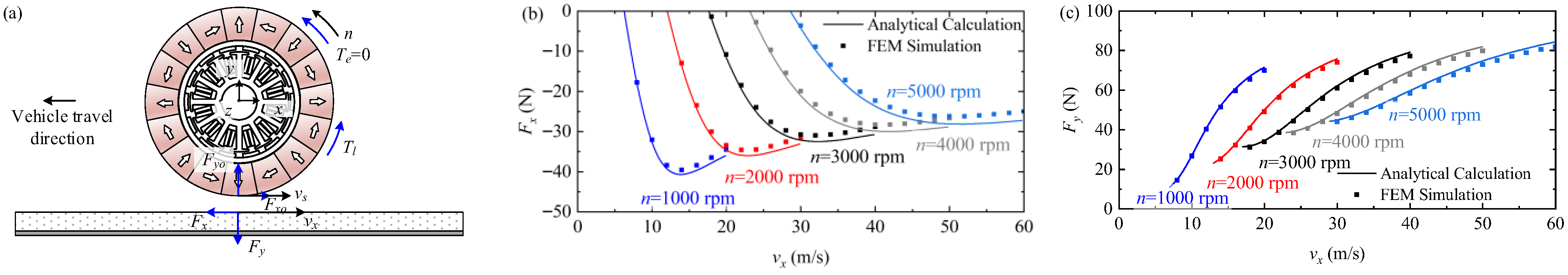

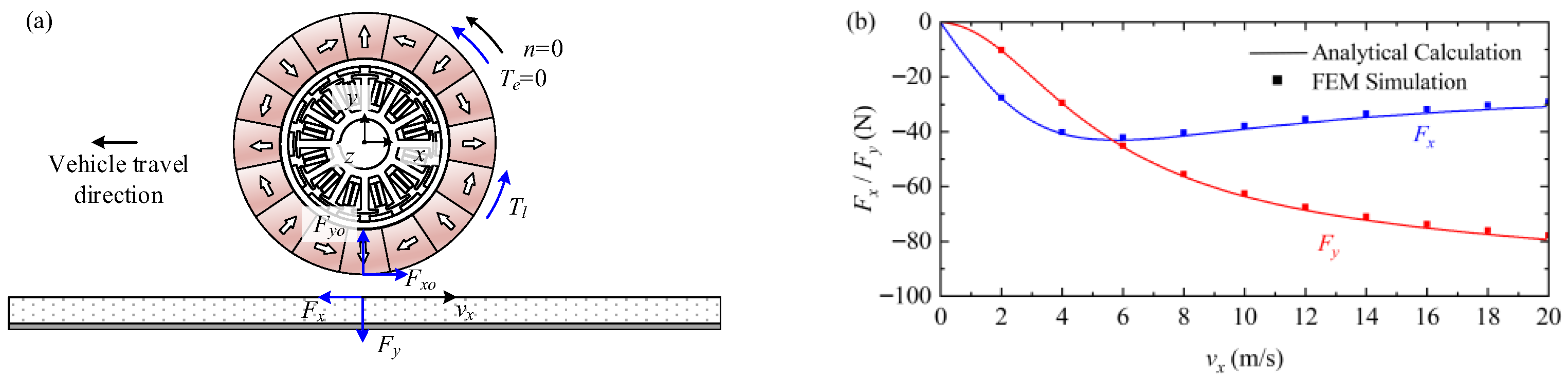

3.3.2. Braking Operation

- (i)

- Regenerative braking

- (ii)

- Plugging braking

- (iii)

- Dynamic braking

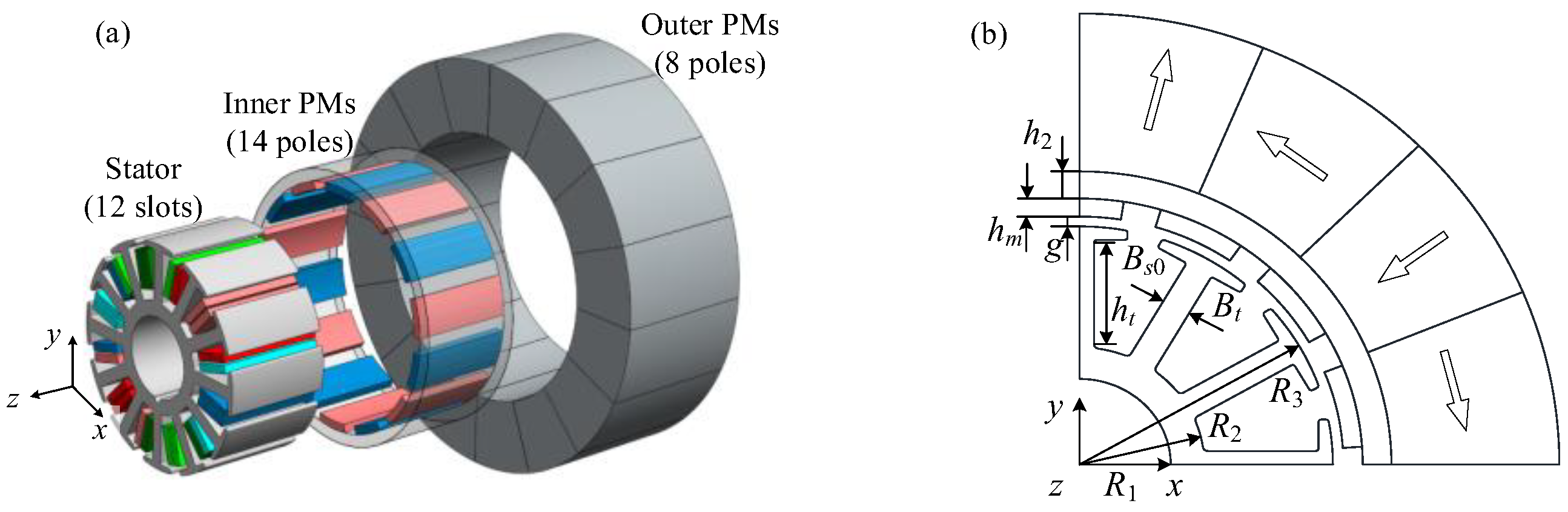

4. Integrated Design of PMEIM

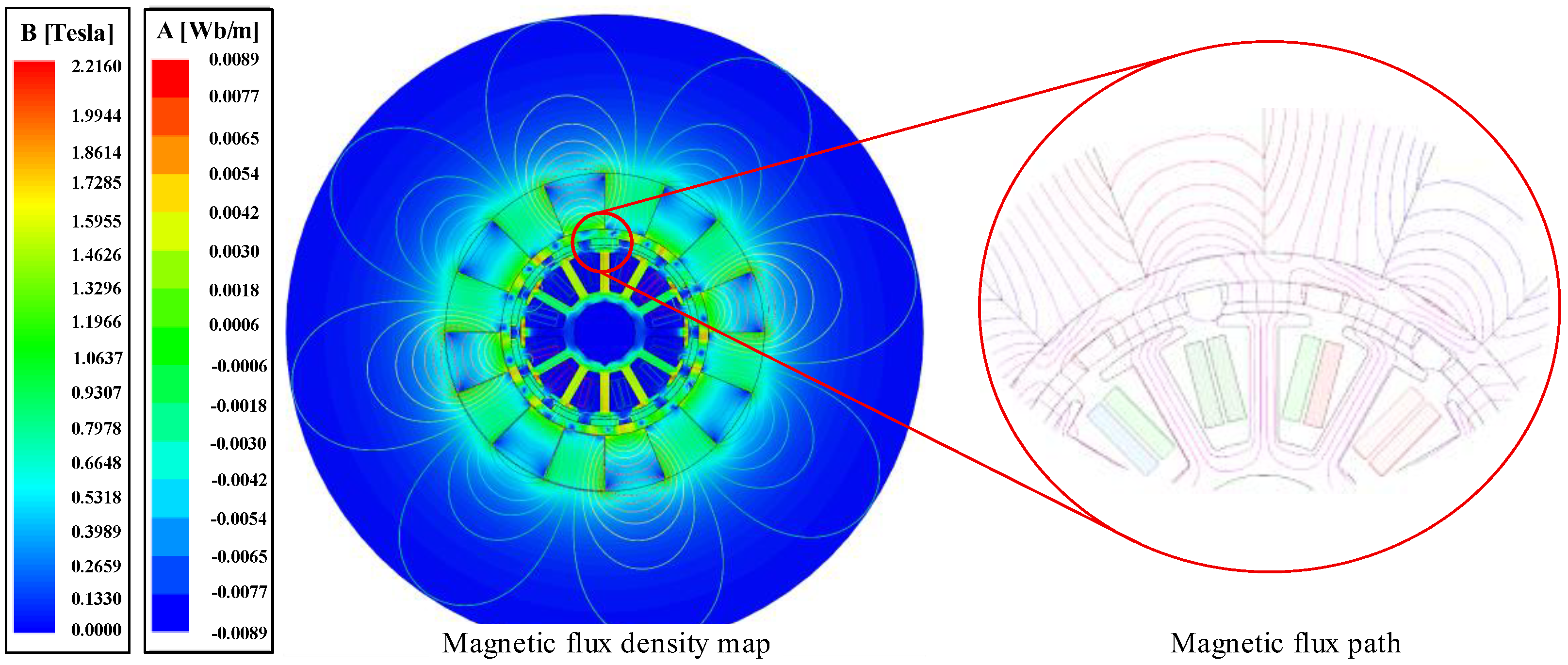

4.1. Electromagnetic Model

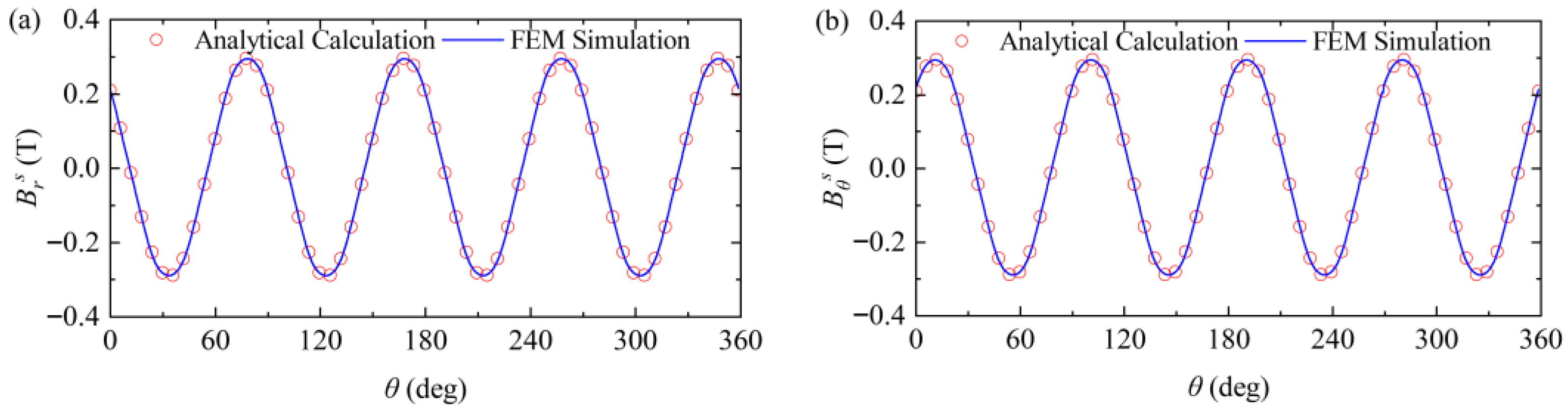

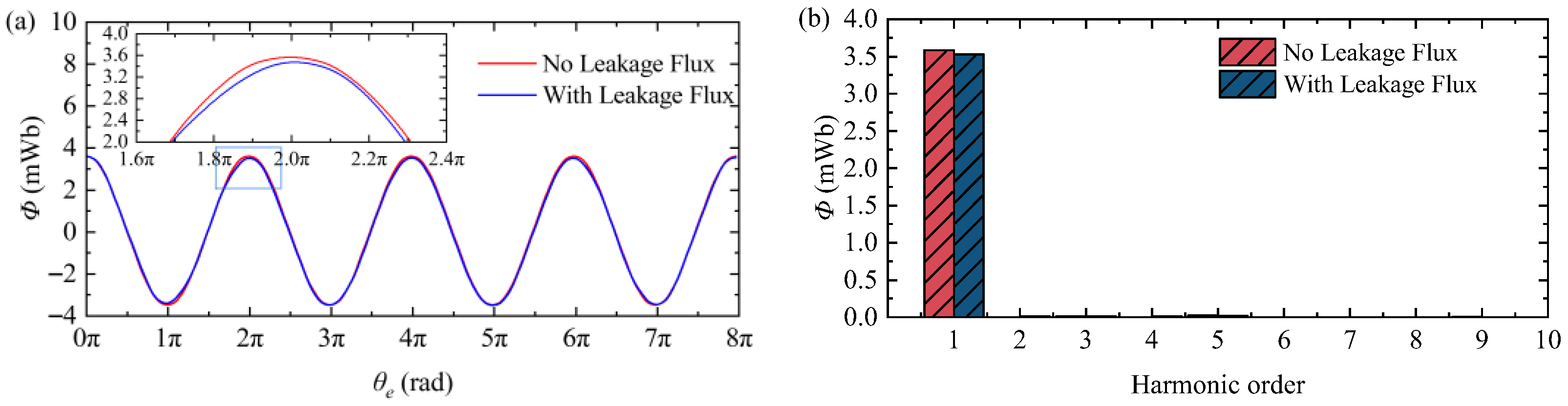

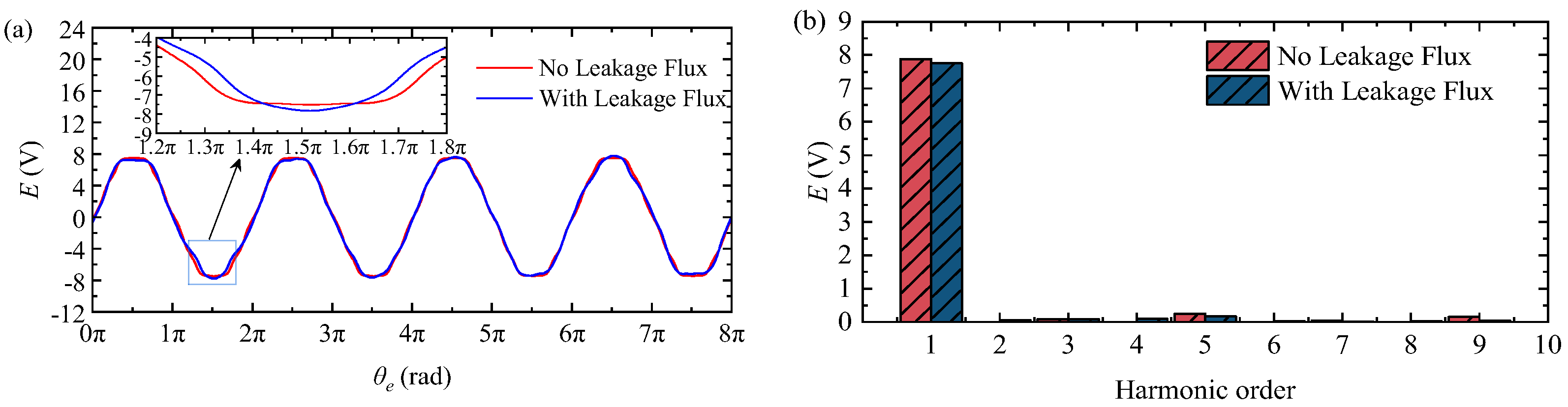

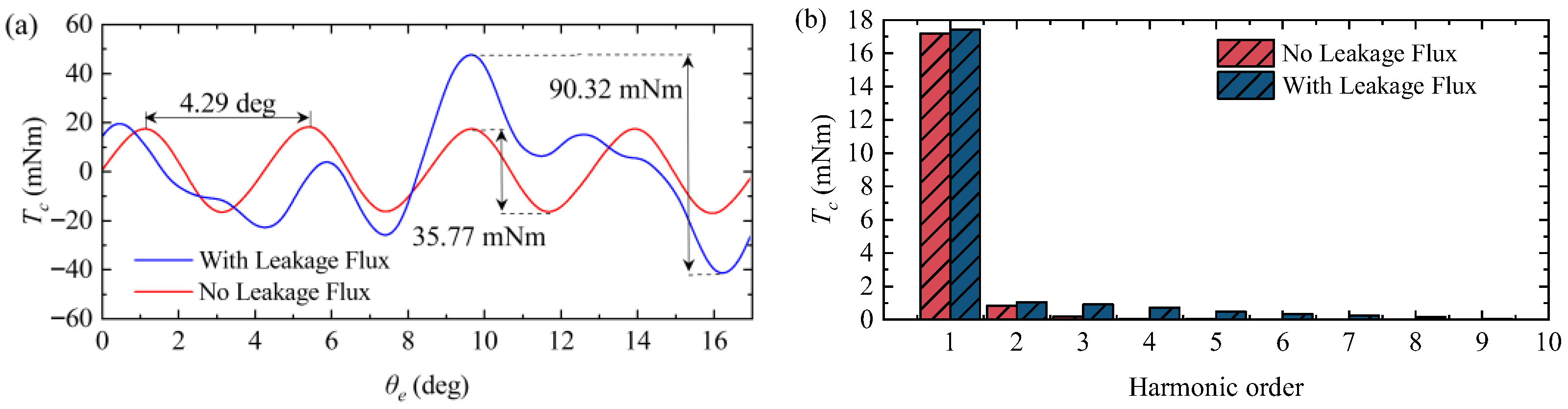

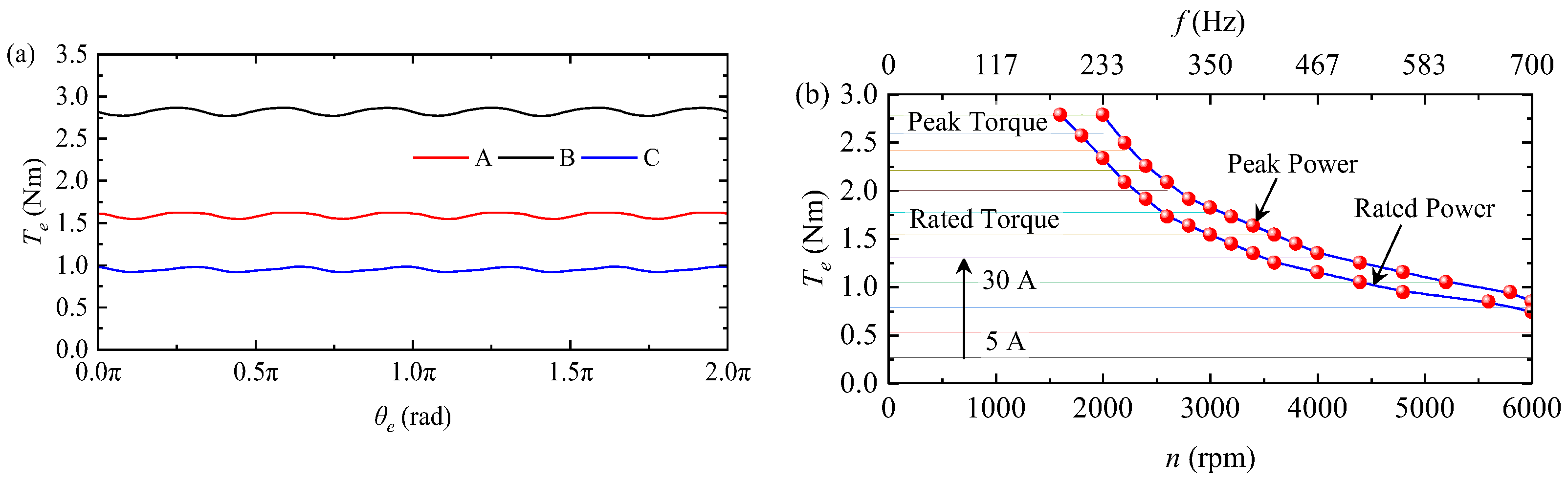

4.2. Electromagnetic Analysis

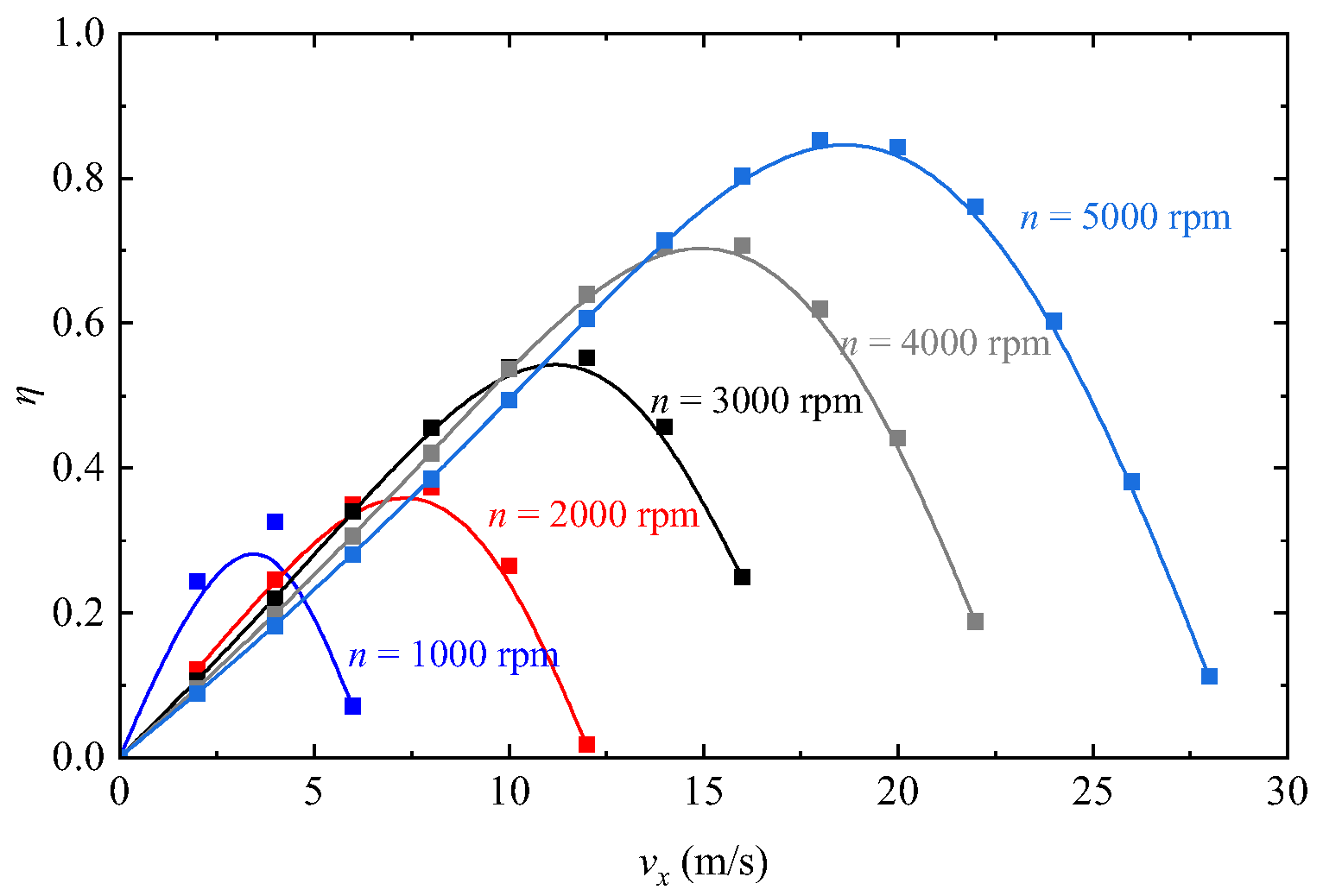

4.3. Efficiency Evaluation

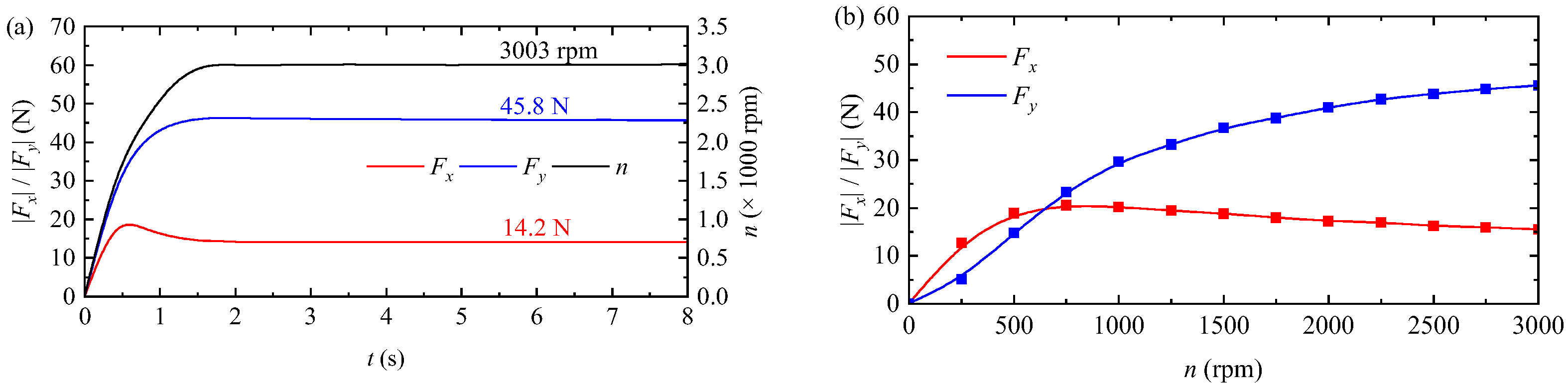

5. Prototype Experiment of PMEIM

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The external magnetic field distribution of the PMEIM is characterized by analytical and FEM approaches. Results indicate that despite the powertrain adopting a Halbach PM array, non-uniformity of the suspension gap causes magnetic field distortion, which presents amplitude-modulated periodic waves on the conductor plate.

- (2)

- The electromagnetic force characteristics of the PMEIM powertrain are analyzed via analytical and FEM methods. The powertrain operating states (motor operation, regenerative braking, plugging braking, and dynamic braking) are calculated and determined.

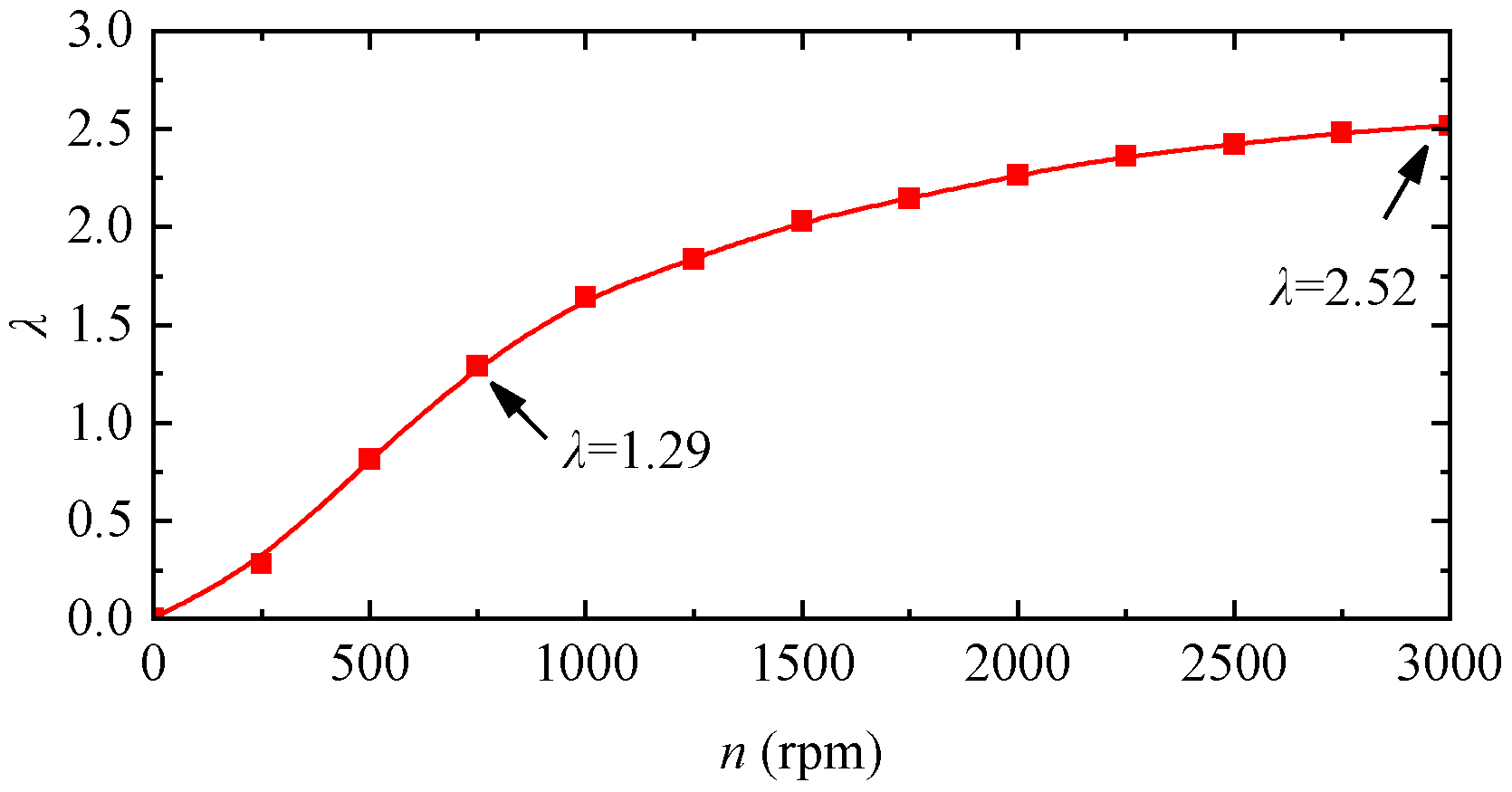

- (3)

- The PMEIM electromagnetic design is conducted on a small-scale PMEIM prototype. Results confirm that, under rated conditions, the measured thrust force and guidance force of the prototype are 14.2 N and 45.8 N, respectively, with a levitation–weight ratio of 2.52. The PMEIM powertrain exhibits integrated levitation and propulsion functions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, H.; Kim, D. Magnetic Levitation: Maglev Technology and Applications; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Guo, J.; Eberhard, G. Review of reaction spheres for spacecraft attitude control. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 91, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Chi, M.; Deng, Z.; D’Ovidio, G. Design and parametric analysis of linear synchronous motor with a novel electromagnetic Halbach array in HTS maglev system. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2025, 58, 315001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Gao, T.; Liu, M.; Sharma, S.; Dambatta, Y.; et al. Magnetic bearing: Structure, model, and control strategy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 131, 3287–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rametti, S.; Pierrejean, L.; Hodder, A.; Paolone, M. Pseudo-Three-Dimensional Analytical Model of Linear Induction Motors for High-Speed Applications. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 9109–9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, J.; Ren, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Gao, P.; Lin, Q.; Song, B. A High-Temperature Superconducting Maglev Ring Test Line Developed in Chengdu, China. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 3602408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Luo, J.; Ma, G.; Liu, K.; Cui, L.; Wang, Y. Fast and Precise Calculation of Mutual Inductance for Electrodynamic Suspension: Methodology and Validation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 6046–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, W.; Ge, J.; Shangguan, Y.; Xiao, H.; Tang, Y. A Positive- and Negative-Sequence Equivalent Circuit Model for Linear Induction Machine Adapted to Urban Rail Transit. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 9630–9641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, W.; Jing, Y. 3D Analytical Model of Permanent Magnet and Electromagnetic Hybrid Halbach Array Electrodynamic Suspension System. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2020, 15, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.; Lipo, T. Calculating the forces created by an electrodynamic wheel using a 2-D steady-state finite-element method. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2008, 44, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, K.; Rotaru, M.; Sykulski, J. Analysis and Optimization of Asymmetrical Double-Sided Electrodynamic Suspension Devices. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 8300605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, G.; Wang, D.; Xu, J. Dynamic characterization of permanent magnet electrodynamic suspension system with a novel passive damping magnet scheme. J. Sound Vib. 2025, 599, 118849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, G.; Fan, Y. Braking force characteristics of permanent magnet eddy current brake with high acceleration. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2020, 63, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, N.; Nonaka, S.; Hayashi, G. Design of magnet wheel integrated own drive. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1999, 35, 4013–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, N.; Chida, M.; Ogawa, K. Three-dimensional force of magnet wheel with revolving permanent magnets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1997, 33, 4221–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Bobba, D.; Paudel, N.; Bird, J. Source Field Modeling in Air Using Magnetic Charge Sheets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2012, 48, 3879–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.; Lipo, T. An electrodynamic wheel: An integrated propulsion and levitation machine. In Proceedings of the IEEE IEMDC, Madison, WI, USA, 1–4 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; As’arry, Z.; Zhu, L.; Hairuddin, A.; Hassan, M.; Zain, M. Enhancing ride comfort of semi-active suspension through collaboration control using dung beetle optimizer optimized Fuzzy PID controller. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2025, 17, 16878132251314332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hao, R.; Zhang, S.; Lin, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y. Vehicle semi-active air inerter-spring-damper suspension with frequency-varying negative stiffness: Design, control, and experimental validation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2026, 244, 113740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ke, Z.; Shi, H.; Deng, Z. Investigation of RBF-SMC Control Strategy for Vertical Dynamics of Maglev Car Considering Temperature Rise Effects. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2025, 10, 3560–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Shi, H.; Ke, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y. Permanent Magnet Electrodynamic Suspension System Integrated with a Car: Design, Implementation, and Test. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Deng, Z.; Liang, L.; Li, K.; Lu, H.; Zheng, J. Levitation–guidance–propulsion integrated design for maglev trains based on oblique ring Halbach permanent magnet wheels. Electr. Drive Locomot. 2023, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, L.; Liu, X.; Deng, Z. Novel design of magnetization and study of magnetic force characteristics of annular Halbach permanent magnet electrodynamic wheel. Electr. Drive Locomot. 2024, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Deng, Z.; Lv, C.; Shi, H.; Zhu, H.; Hu, X.; Liang, L.; Deng, J.; Wu, X. Exploration of Propul-sion-Guidance System for HTS Maglev Based on Permanent Magnet Electrodynamic Wheel. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 3600111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, X.; Deng, Z. Lateral Dynamic Performance of High-Temperature Superconducting Pinning Maglev Vehicle Driven by Electrodynamic Wheel at Medium and Low Speed. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2023, 34, 3601108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bi, J.; Liang, L.; Lin, W.; Liang, X.; Xu, L.; Deng, Z. Dynamic Characteristics Measurement and Analysis of HTS Maglev Vehicle Driven by Permanent Magnet Electrodynamic Wheel. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 6010414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Howe, D. Analytical magnetic field analysis of Halbach magnetized permanent-magnet machines. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2004, 40, 1864–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, N.; Bird, J. General 2-D Steady-State Force and Power Equations for a Traveling Time-Varying Magnetic Source Above a Conductive Plate. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2012, 48, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Symbols | Nominal Values |

|---|---|---|

| Pole pairs | p | 4 |

| Inner radius | Ri | 32.5 mm |

| Outer radius | Ro | 50 mm |

| Wheel width | Wm | 35 mm |

| Conductor plate width | Wp | 100 mm |

| Conductor plate thickness | d | 10 mm |

| PMs remanence | Bre | 1.23 T |

| Conductor plate conductivity | σ | 5.8 × 107 S/m |

| Parameters | Symbols | Nominal Values | Parameters | Symbols | Nominal Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rated speed | nN | 3000 rpm | Peak speed | np | 6000 rpm |

| Rated torque | TN | 1.57 Nm | Peak torque | Tp | 2.80 Nm |

| Rated power | PN | 495 W | Peak power | Pp | 586 W |

| Parameters | Symbols | Values | Parameters | Symbols | Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner radial | R1 | 9.5 mm | Pole arc coefficient | αp | 0.7 |

| Middle radial | R2 | 13 mm | Thickness of rotor yoke | h2 | 3 mm |

| Outer radial | R3 | 26.4 mm | Slots and poles | z/2p | 12/14 |

| Axial length | Lef | 25 mm | Pitch | y | 1 |

| Tooth depth | ht | 11.25 mm | Conductors per slot | Ns | 14 |

| Tooth width | Bt | 3 mm | Parallel strands | n | 1 |

| Slot width | Bs0 | 3.5 mm | Parallel branches | a1 | 1 |

| Airgap | g | 1.1 mm | PMs type | Bre | 1.23 T |

| Thickness of PM | hm | 2 mm | Winding type | σ | 5.8 × 107 S/m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ding, Z.; Bi, J.; Wu, S.; Lv, C.; Chi, M.; Deng, Z. Design and Investigation of Powertrain with In-Wheel Motor for Permanent Magnet Electrodynamic Suspension Maglev Car. Actuators 2026, 15, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010058

Ding Z, Bi J, Wu S, Lv C, Chi M, Deng Z. Design and Investigation of Powertrain with In-Wheel Motor for Permanent Magnet Electrodynamic Suspension Maglev Car. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Zhentao, Jingguo Bi, Siyi Wu, Chong Lv, Maoru Chi, and Zigang Deng. 2026. "Design and Investigation of Powertrain with In-Wheel Motor for Permanent Magnet Electrodynamic Suspension Maglev Car" Actuators 15, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010058

APA StyleDing, Z., Bi, J., Wu, S., Lv, C., Chi, M., & Deng, Z. (2026). Design and Investigation of Powertrain with In-Wheel Motor for Permanent Magnet Electrodynamic Suspension Maglev Car. Actuators, 15(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010058