1. Introduction

Magnetic bearings have great potential to become a key component of complex and high-speed machines such as control moment gyroscopes, cryogenic pumps and compressors, turbomachinery, rotary instruments, and flywheels. Further improvements in AMB design are necessary, focusing on improving key characteristics such as load capacity, mass, power consumption, stiffness, damping, heat dissipation, and cost. One promising approach is to investigate a hybrid system using permanent magnets in AMB technology.

The hybrid bearing operation is similar to that of the classical AMB, using sensors and control coils to maintain the equilibrium position of the rotor. Both systems require a bias magnetic flux for linearization. The key difference between classical and hybrid AMB systems lies in how the required bias magnetic flux is generated. In the hybrid system, permanent magnets provide the bias magnetic flux (PM-bias). The classical AMB system requires additional power consumption to generate this flux. This difference could theoretically lead to a reduction in mass, power consumption, generated heat, and cost.

The idea of using a permanent magnet to provide the bias magnetic flux was first proposed for radial bearings [

1,

2,

3]. Research and development of radial PM-bias bearings continued, focusing on the reduction of bearing mass and power consumption, particularly for potential applications in aircraft gas turbine engines [

4,

5,

6]. The design of an axial PM-bias bearing was later proposed, with the permanent magnets fixed to the stator in order to avoid high stresses due to centrifugal loads [

7]. Further mass reduction of the rotor suspension can be achieved by combining PM-bias bearings with a permanent magnet AC motor [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

In the proposed design of the combined axial and radial hybrid active magnetic bearings, low power consumption, mass reduction, and cost savings are achieved [

13,

14]. However, when a separate axial magnetic bearing with low power consumption is required, the proposed design of the axial bearing results in a relatively large axial dimension.

The further development of the PM-bias field was studied by Xu et al. [

15,

16]. The work focused on implementing a controllable PM-bias field using a low-coercivity magnet equipped with magnetization coils. The proposed design, unlike that of other PM-bias bearings, helps to reduce losses by adjusting the generated PM-bias field. Another interesting idea was proposed by Zhao et al. [

17], who applied a modular PM-bias bearing to achieve the required load-carrying capacity, thus significantly reducing the cost of the system. Jin et al., Wu et al., and Yu et al. proposed combined axial and radial PM-bias bearings, resulting in a 3-DOF hybrid AMB, and provided design optimizations aimed at improving load capacity [

18,

19,

20]. Wang et al. proposed the axial PM- biased bearing design by adding a PM ring to each of two separate electromagnets [

21], while the most recent research by Chiu et al. shows proof-of-concept demonstrations for a hybrid magnetic bearing system, confirming the feasibility of PM-bias AMBs in practical setups [

22].

The performance of PM-bias AMBs greatly depends on the unitized control algorithm. Since the electromagnetic and PM fluxes are coupled, the resulting PM-bias bearing system is nonlinear. Wen et al. proposed a linearization-based control method for a flywheel suspension system with a PM-bias bearing [

23]. Liu et al. and Yao et al. proposed linear control algorithms for zero-bias-current AMBs, which are similar to PM-bias AMBs in that they exhibit high nonlinearity and poor controllability [

24,

25]. Another possible control strategy for PM-bias AMBs can be based on the gain-scheduled control for the asymmetric thrust magnetic bearings [

26]. Therefore, the proposed algorithms can also be implemented for PM-bias AMBs.

On the other hand, Chen et al. proposed the use of a fuzzy neural network with an adaptive differential evolution-based dynamic bias current control strategy for the classical AMBs, aiming to decrease the power losses caused by the bias current—a concept similar to that of PM-bias [

27]. Additionally, Xu et al. and Loginov et al. proposed the use of universal adaptive control systems based on a dual closed-loop control strategy, which can be implemented for both classical and PM-bias AMBs [

28,

29]. Xiang et al. show the importance of accurate PM-flux determination in order to accurately determine PID gains to provide stable operation of the nonlinear PM-bias AMBs [

30]. Nehal et al. proposed the use of complex optimization techniques for AMB systems, such as metaheuristic algorithms, multi-objective optimization, and AI-powered strategies to deal with AMBs’ nonlinear behavior [

31].

It should be noted that even though PM-bias bearings consume less electrical power, they still exhibit negative effects caused by eddy currents, similarly to the classical AMBs. However, unlike the rectangular cores [

32] or radial AMBs [

19,

33], whose rotors and stators can be laminated, such lamination is not feasible for the axial bearing. For the classical AMBs, Whitlow, Spece, Fittro et al. proposed an improvement of the axial AMB, focusing on its dynamic performance, achieving this also by a stator segmentation of the axial AMB, which increases the system bandwidth and reduces the negative effects of eddy currents [

34,

35]. Jastrzebski et al., Wang and Le et al. successfully tested the segmented axial AMB for compressor applications [

36,

37,

38]. Another way to improve the dynamic stability of the hybrid magnetic bearings, including those with PM, is to use viscous fluids to improve their damping characteristics, which has found application in various medical devices [

39,

40]. In the case of superconducting magnetic bearings [

41,

42] or thrust bearings for marine applications [

43], permanent magnets can be used to improve the thrust bearing stiffness.

Passive magnetic bearings (PMBs), which consist of only permanent magnets, are an alternative approach to zero power consumption magnetic bearings [

44,

45,

46]. While PMBs are distinguished by simplicity and zero power consumption, their lack of active control and limited damping properties make hybrid PM-bias AMBs a possible compromise for solutions requiring both energy efficiency and controllability.

The previously proposed promising designs of PM-bias axial bearings, including those based on controllable PM-bias fields and modular PM-bias concepts, are well-suited for ground-based applications, but tend to have increased mass for axial application compared to the design proposed by Allaire, Nichols et al. [

47,

48], thus limiting their suitability for aviation use. One of the objectives of this work is to improve the previously proposed design of the axial hybrid active magnetic bearing [

47,

48] and to compare its performance with that of a classical axial AMB.

In addition to damping lack and high nonlinearity, another major limitation of PM-bias bearings is the temperature limitation of permanent magnets. NdFeB magnets have a maximum operating temperature of 80 °C [

48]. This issue can be partially solved by using high-temperature NdFeB magnets [

49] (e.g., N38H, which can withstand up to 120 °C), SmCo (200–550 °C) [

50,

51], or AlNiCo (up to 450 °C) [

15,

16]. FE thermal analysis can be used to accurately determine thermal distribution in various electromagnetic devices, including axial AMBs [

52] and permanent magnet synchronous machines [

53]. The importance of thermal analysis for AMBs also arises from the fact that eddy currents, hysteresis, and copper and iron losses lead to an increase in temperature, which in turn negatively affects the AMB performance (increased coil resistance, reduced magnetic permeability). These phenomena can be evaluated by performing electromagnetic–thermal coupled analyses [

54,

55]. In order to reduce the temperature of AMB actuators, an increase in heat dissipation can be achieved through the use of water- or air-cooling schemes, or by designed optimization focused on loss reduction [

56,

57]. It is known that the bias current reduction will lead to better thermal behavior of the AMB [

58]. The existing research on axial PM-bias bearings has not considered thermal analysis and heat dissipation, which are important factors limiting their application. Thermal analysis will be addressed in this paper.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analytical Model of the Classical AMB

In order to compare the performance of the hybrid axial AMB with that of the classical design, both the magnetostatic and thermal analytical models are developed and presented for each configuration (

S1 Matlab_classical_axial_AMB_model.txt). The calculation of these models provides the initial geometric parameters for both bearing designs, which are then used for more accurate finite element analysis. The classical AMB design is shown in

Figure 1.

The analytical model of the classical axial AMB is based on the balance of the inner and outer poles of the axial electromagnet to saturate the same coil current [

59]. The pole area is as follows:

where F is the bearing load capacity,

is the permeability constant, and

is the flux density.

According to the balance assumption, the radial thickness of the inner pole is as follows:

where

is the inner diameter of the electromagnet.

The same approach is used to determine the radial thickness of the outer pole:

where

is the outer diameter of the electromagnet. The area covered by the radial component of the stator should be at least equal to the pole area:

Similarly, the thrust disk thickness is

The copper slot depth can be determined using the following equation:

where

is the current density,

is the maximum coil current,

is the wire cross-sectional area,

is the copper slot area fill factor,

is the air gap, and

is the copper slot height.

Using the initial data, the number of wire turns can be determined as follows, with the assumption of the flux leakage absence [

59]:

Next, it is necessary to determine the power of the heat losses in the coil and the wire temperature. The coil resistance is given by

where

is the copper resistivity, and

is the mean coil turn length.

The maximum power of the coil heat losses can be determined as follows:

To determine the maximum wire temperature, it is necessary to calculate the heat transfer from the coil to the housing and to the air. The calculation is based on Ohm’s law for steady-state heat flow. A portion of the heat flow is transferred directly to the air. The thermal resistance from the coil to the air can be calculated as follows:

where

is the heat transfer coefficient from the coil to the air, and

is the front area of the coil slot.

The remaining heat flow is transferred from the coil to the stator through the insulation area (

), which has a thermal conductivity coefficient (

) and an insulation thickness (

):

The thermal resistance of the soft magnetic alloys is much smaller than that of the insulation, i.e., it is not considered in this calculation. The heat flow from the electromagnet stator either dissipates into the air or is transferred to the housing. If the electromagnet stator is press-fitted into the housing, it can be assumed that the stator temperature is equal to the temperature of the housing near the electromagnet. However, the maximum possible temperature can be calculated by assuming that the heat flow transfers from the stator directly to the ambient air. The thermal resistance from the stator to the air is calculated as follows:

where

is the heat transfer coefficient from the stator to the air, and

is the outer surface area of the electromagnet. Finally, the wire temperature can be determined using the following equation:

where

is the ambient air temperature.

If the coil bobbin is used,

should be replaced with the combined thermal resistance from the coil to the bobbin (

) and bobbin to air resistances (

):

The thermal calculation ends by comparing the winding temperature with the permissible temperature of the insulation material (110–180 °C).

2.2. Analytical Model of the Hybrid AMB

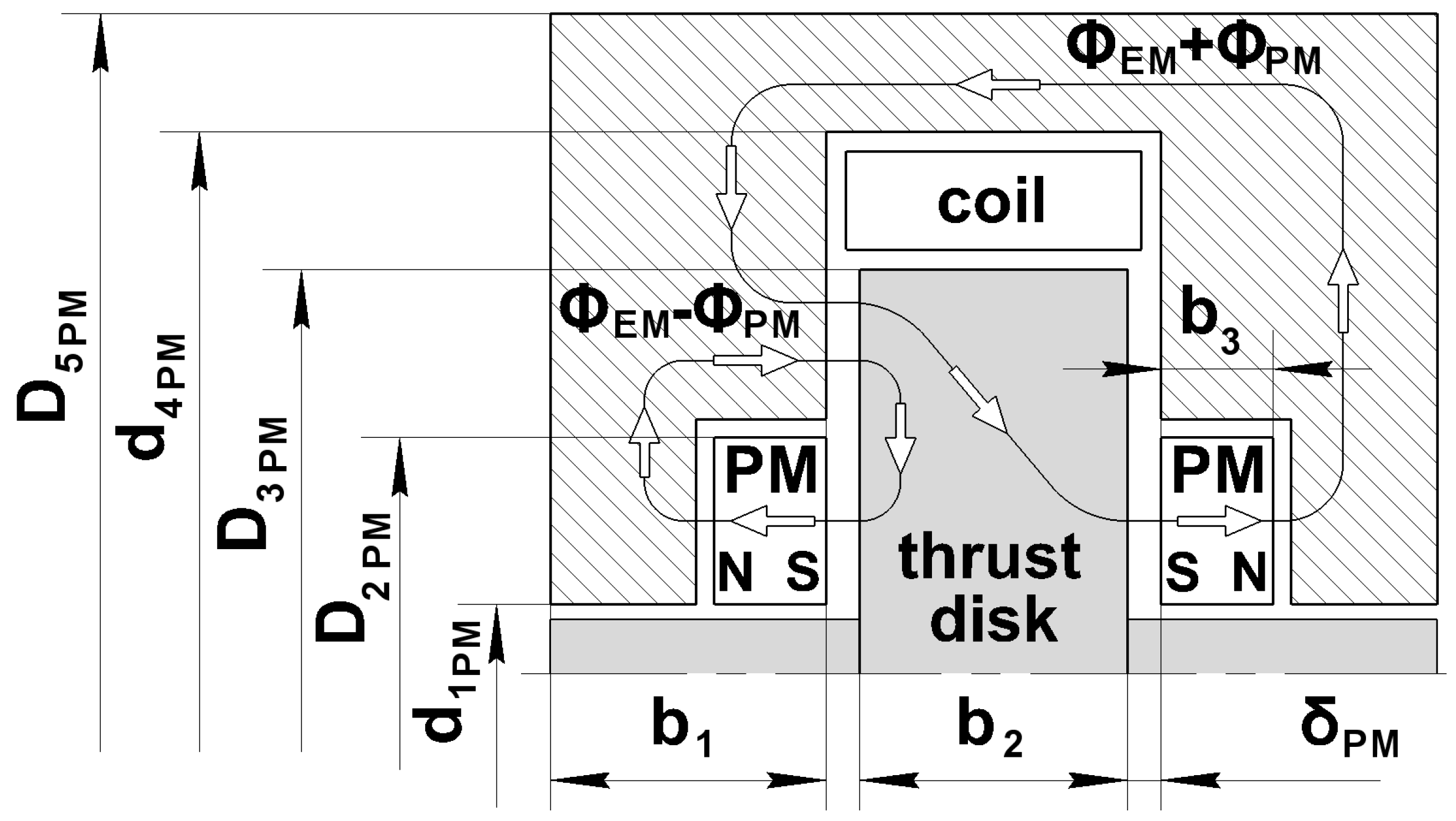

Unlike the classical axial AMB, which has two separate axial electromagnets, the proposed hybrid bearing has a single coil (

Figure 2). This coil is mounted on the upper diameter of the rotor thrust disk. The rings of permanent magnets are installed on both sides of the electromagnet stator. These permanent magnets provide the bias magnetic flux. By adjusting the current in the coil and changing its direction, the total magnetic flux on each side can be adjusted (subtracting on one side while adding to the other), with the use of a single power amplifier. The magnetostatic and thermal analytical models are developed (

S2 Matlab_hybrid_axial_AMB_model.txt).

The magnet circuit generated by the PM consists of two reluctances in series: the reluctance of the PM and the air gap reluctance.

where

is the area of the magnet facing the thrust disk;

;

is the area of the thrust disk;

is the fringing factor;

is the air gap in the PM-bias bearing;

is the thickness of the permanent magnet, and

is the relative permeability of the PM material.

The total reluctance determines the flux produced by the PM:

where

is the coercive field strength of the PM.

Thus, the PM flux densities for the and , where is the area of the magnet core material facing the thrust disk that can be determined.

The magnetic flux density in the gap generated by an electromagnet can be determined using Ampere’s law:

where N is the number of coil turns;

I is the coil current. The net load-carrying capacity of the PM-bias AMB is determined by the sum of the squares of the EM and PM flux densities in the two air gaps, corresponding to the areas

and

, respectively:

Since

, Equation (21) can be simplified as

Either number of coil turns (N) or the thrust disk area, facing the magnet core material (

) and consequently its outer diameter (

), can be found by setting the target load-carrying capacity of the PM-bias AMB (

) and using a root nonlinear function:

Unlike in the classical axial AMB model, for the PM-biased design, the coil wire diameter is determined based on the current density:

The area covered by the radial component of the stator should be at least equal to the pole area (

). Similarly, for the thrust disk thickness:

where

is the outer diameter of the PM ring.

The coil outer diameter can be determined:

where

is the outer diameter of the thrust disk for the PM-biased AMB.

The cross-sectional area of the magnet core should also be at least equal to the pole area; thus, the outer diameter of the magnet core is as follows:

The coil temperature analytical model calculation technique is similar to that for the classical axial AMB (based on Ohm’s law). The coil resistance and maximum power of the coil heat losses are calculated using Equations (8) and (9). The maximum possible temperature can be calculated by assuming that the heat flow transfers from the stator directly to the ambient air.

The thermal resistance from the coil to the air, from the coil to the stator, and from the stator to the ambient air can be calculated using Equations (10)–(12). Finally, the wire maximum temperature can be determined using Equations (13) and (14).

2.3. Numerical Models of the Classical AMB

The FEMM solver makes certain assumptions when addressing magnetostatic problems using Maxwell’s equations. The program solves only low-frequency electromagnetic problems, where the influence of eddy currents can be neglected [

60]. Therefore, it is not possible to determine the negative influence of induced eddy currents on AMB performance; however, in operation, they lead to increased power losses and limit high-frequency control performance, i.e., the achievable control bandwidth. For more accurate prediction of eddy-current negative influence in AMBs, more advanced analytical modeling or FEM analysis can be used [

34,

61].

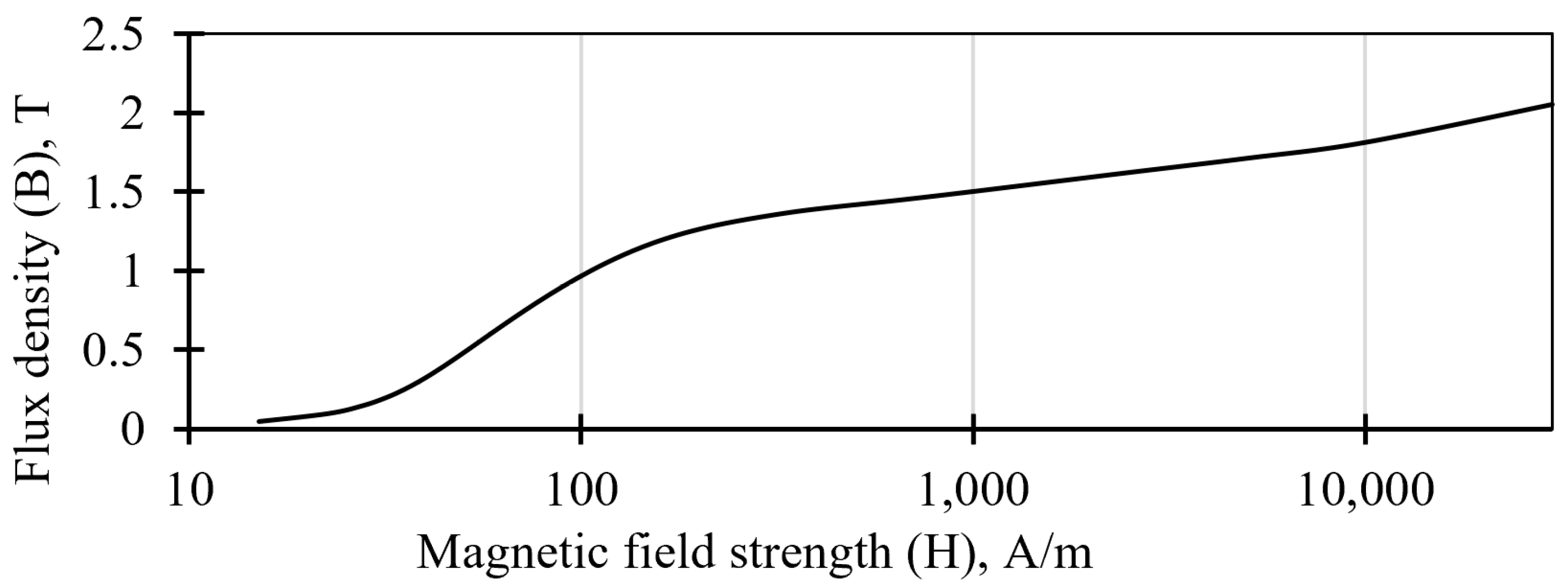

The axisymmetric problem, utilizing a cylindrical coordinate system, is used for the axial AMB. The prescribed “A” boundary condition (Dirichlet type) is applied. Soft magnetic material 10880 was used for fabricating the magnetic core [

62]. The nonlinear B–H curve was used. It is shown in

Figure 3. The properties of the 10880 material are presented in

Table 1 for comparison with other widely used soft magnetic materials, available in the form of round bars, required for axial AMB fabrication [

63,

64]. The copper coil parameters are as follows: linear B–H dependence, isotropic relative magnetic permeability

, wire specific conductivity

, and single-core wire.

The axial AMB consists of two electromagnets, each with its own electric circuit. The current values are set separately for each circuit. The coils of the electromagnets are connected in series.

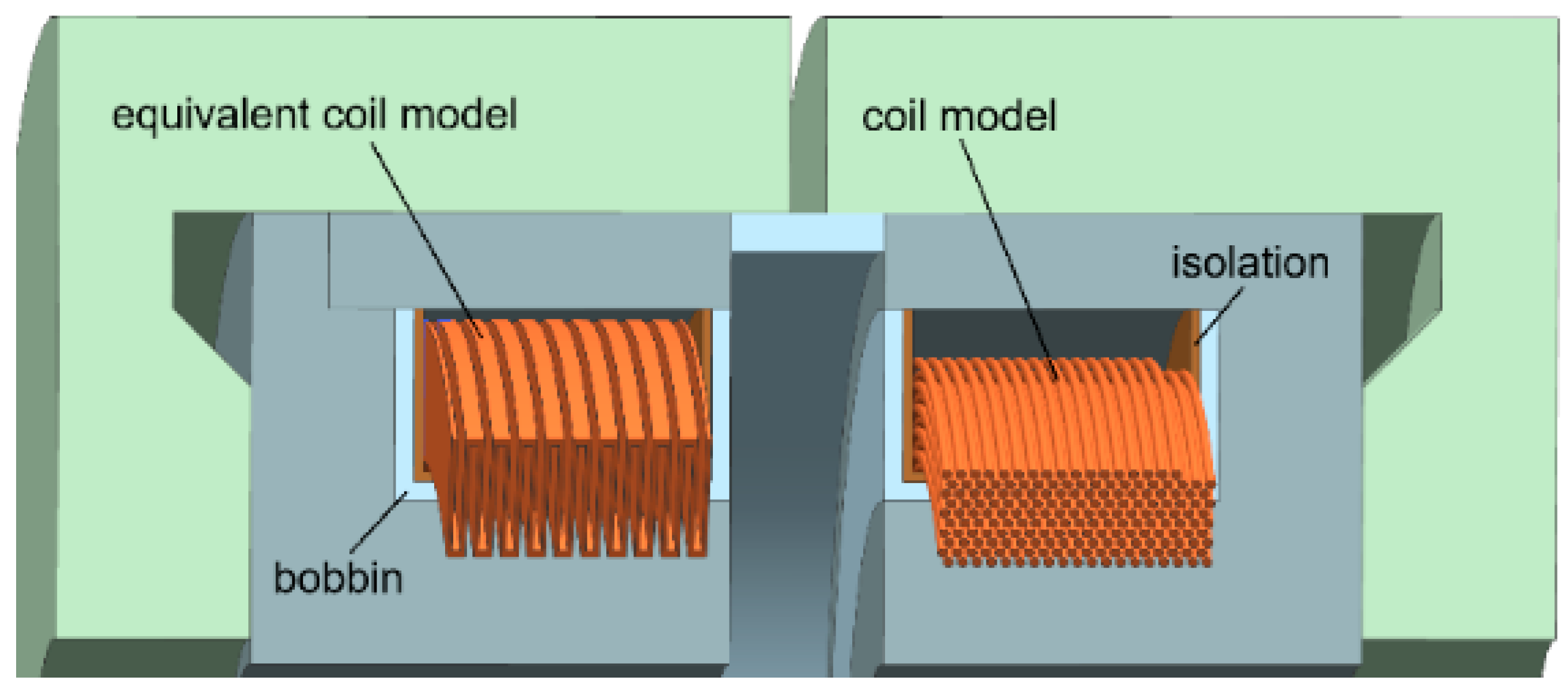

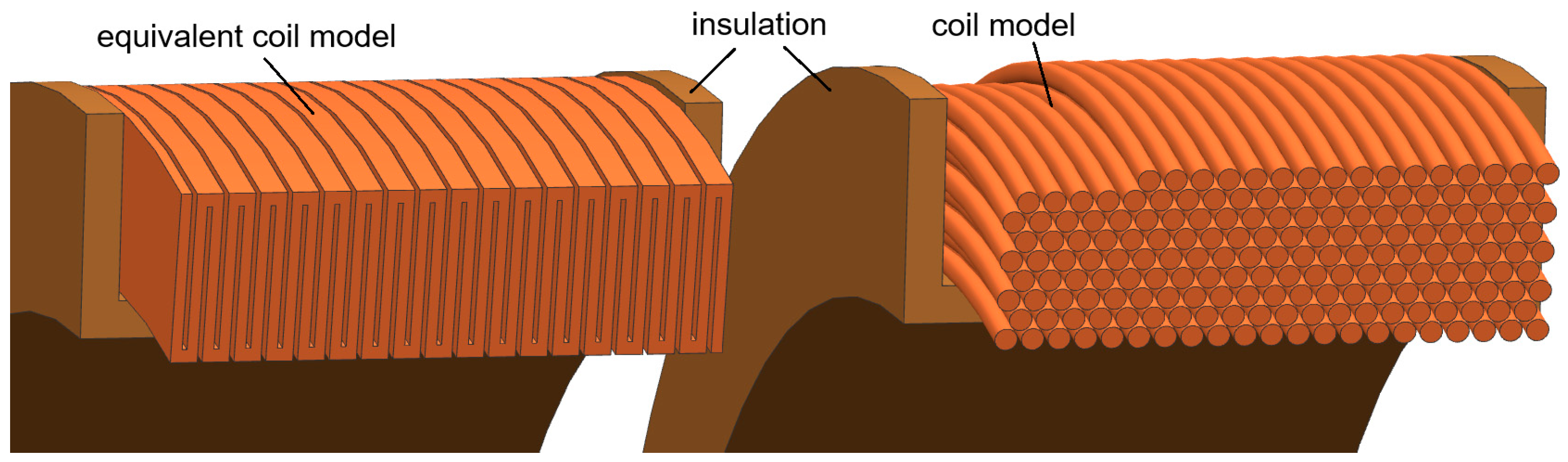

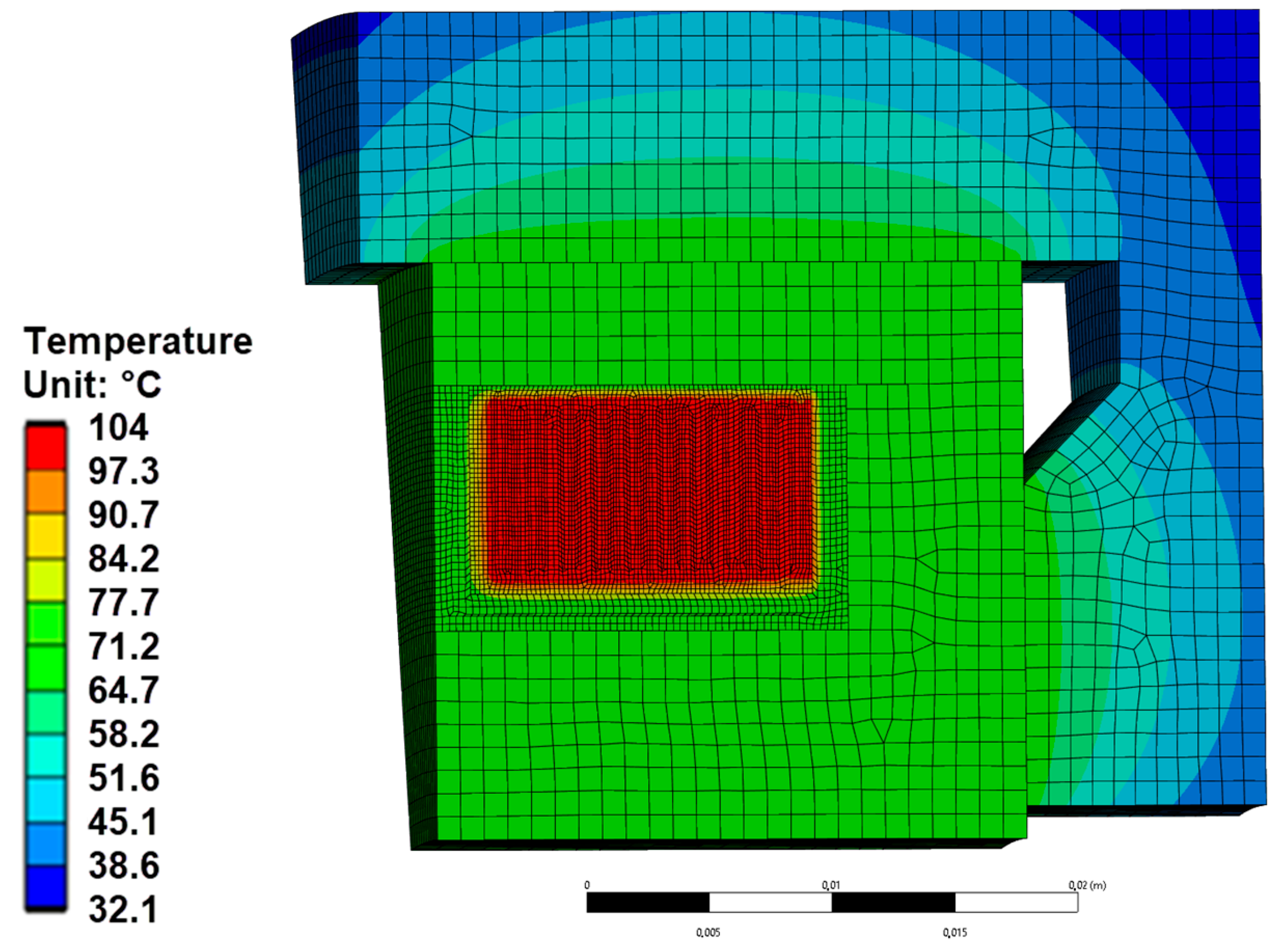

For the development of the steady-state thermal model (

S5 FEMM_Temperature_classical_AMB_model.feh), two approaches have been used. The first one is based on the magnetostatic model of the AMB and is considered in axisymmetric formulations. The second one is a three-dimensional finite element model. The equivalent coil modeling is used for both approaches. The equivalent coil model is the simplified coil representation with a similar volume and external surface area (

Figure 4).

Similarly to the analytical thermal calculation, for both approaches, convection boundary conditions have been applied to the outer surfaces of the coil and stator (the heat transfer coefficient and the ambient air temperature). The thermal conductivity coefficients for copper wire, soft magnetic material, and insulation have been set according to the respective materials. In the calculation, the power consumption of the coil, as determined by the magnetostatic model, has been applied as the volume (internal) heat generation.

2.4. Numerical Models of the Hybrid AMB

The proposed hybrid active magnetic bearing is a PM-bias bearing. A numerical magnetostatic model of the hybrid AMB has also been developed and simulated using the FEMM software (

S6 FEMM_hybrid_AMB_magnetostatic_model.fem). The main difference between the classical and hybrid bearings is the need to accurately set the permanent magnets’ properties.

For the hybrid bearing, the N38H magnetic alloy was used. The magnet’s properties are described by the magnet coercivity. The N38H magnetic alloy has a relative permeability of 1.048, coercivity of 943 kA/m, and magnetic energy of 35.1 MGOe, while its maximum operating temperature is 120 °C. Based on the analytical calculation model result, permanent magnet rings were purchased. The ring geometric parameters were as follows: inner diameter of 30 mm, outer diameter of 40 mm, and thickness of 2 mm. Two rings are installed on each side, so the total thickness of the PM is 4 mm. Soft magnetic material 10880 (Zlatoust steel mill, Zlatoust, Russia) is used for the magnetic core. The hybrid axial AMB consists of one electromagnet, with the coil connected in series.

3. Designs

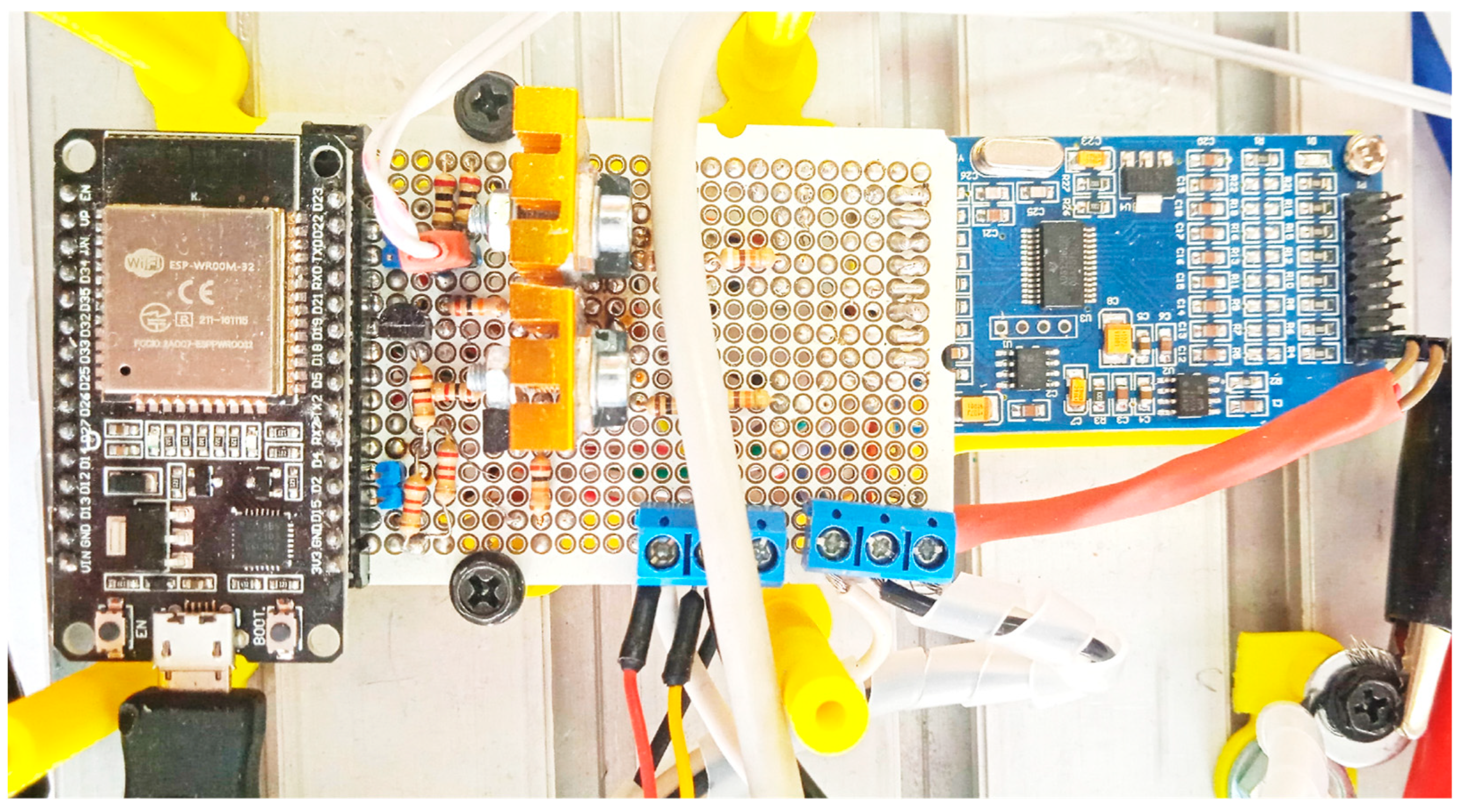

3.1. Digital Control System for the Classical AMB

The cost of the AMB system is relatively high, approximately two to three times greater than that of fluid film or gas static bearing systems [

48,

59], thus preventing the widespread adoption of AMBs. The most expensive components are actuators, amplifiers, a DSP board, and sensors. The state-of-the-art DSPs are produced by Texas Instruments. However, fast and affordable 32-bit DSP microcontrollers, such as the ESP32 or STM32, are now widely available. Therefore, in the paper, an attempt to use the ESP32 DSP has been made.

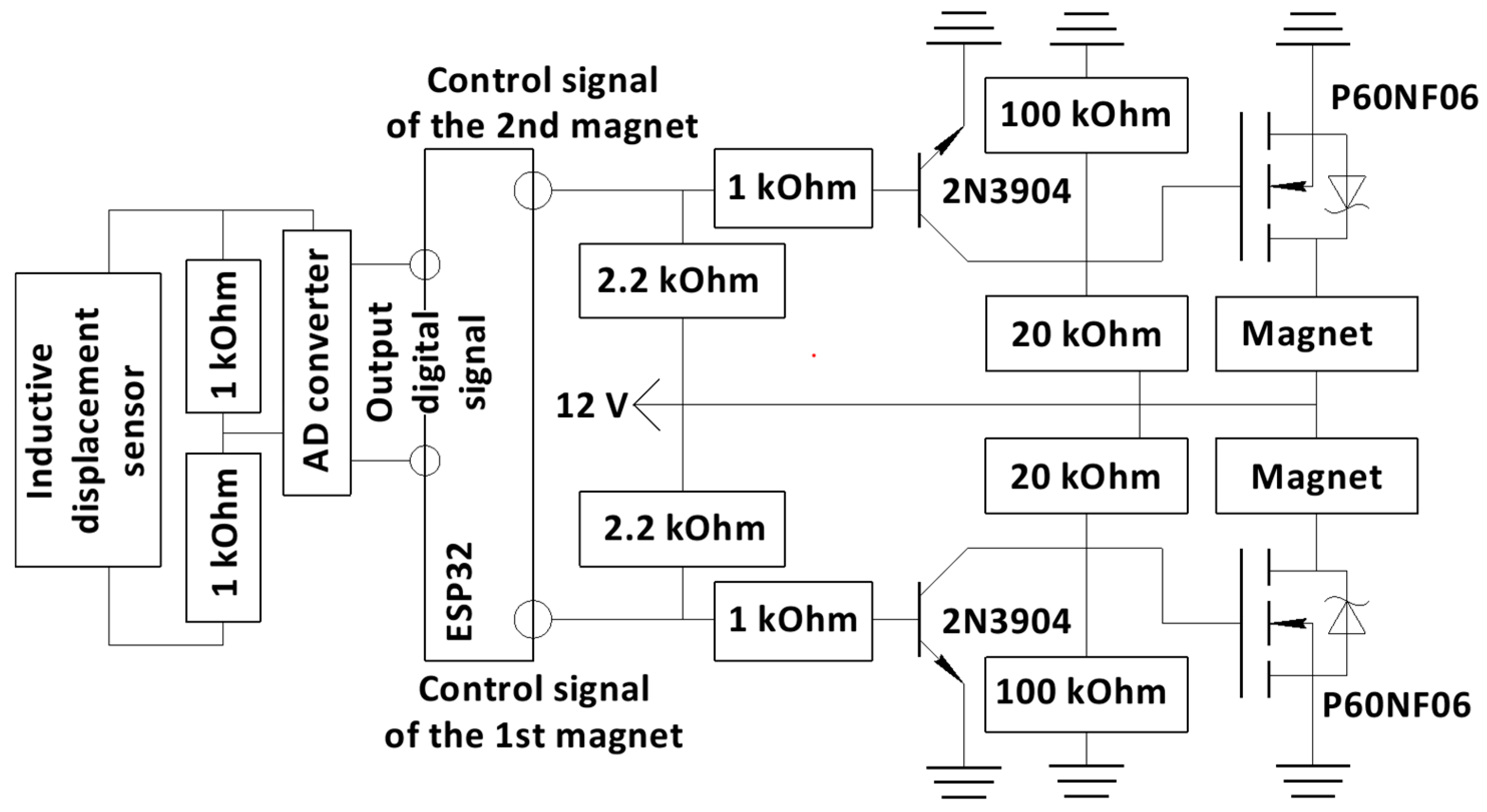

The AMB control system consists of three main components: the rotor axial displacement sensor, the controller board, and the amplifier. A schematic diagram of the system is shown in

Figure 6.

Among other types of displacement sensors for AMB systems, the inductive sensor is one of the most widely used [

65]. The inductive displacement sensor ISAB A41A-43P-5-P is used. It requires conversion of the analog signal to digital using an external ADC (ADS1256). The ESP32 (with a PWM frequency of 240 MHz and a 10-bit clock speed) is used (

S8 Classical_AMB_ESP32_control_programm.txt). Using data from the displacement sensor, the electronic system controls the rotor position by adjusting the current in the electromagnets through an amplifier. A proportional-integral-differential (PID) controller is selected. Before starting the experimental setup operation, the axial equilibrium position of the rotor is automatically determined. Depending on the axial position of the rotor, the inductive sensor sends a signal in the range of 2 to 10 V to the control board. Since the control board cannot read this voltage, a voltage divider is used. The adjusted signal is then sent to the PID controller. Based on the PID coefficients, a correction value is generated and transmitted to the electromagnets using pulse width modulation (PWM). The control signal from the board is directed to the MOSFET P60NF06, thus allowing voltage from the power supply to reach the electromagnets. Since the maximum voltage output from the ESP32 board is 3.3 V, which is insufficient to open the MOSFET, the circuit incorporates a 2N3904 transistor. The control signal first activates the 2N3904 transistor, which then opens the gate of the P60NF06 MOSFET.

The following PID gains were used: Kp = 0.27, Ki = 0.002, and Kd = 15. The sensor measurement update rate was set to 30 kHz. The PWM frequency was set to 1 kHz, which is relatively low for precise AMB current control; however, the developed setup was designed and fabricated only for demonstration and study purposes, resulting in a current loop bandwidth of approximately 250 Hz.

3.2. Digital Control System for the Hybrid AMB

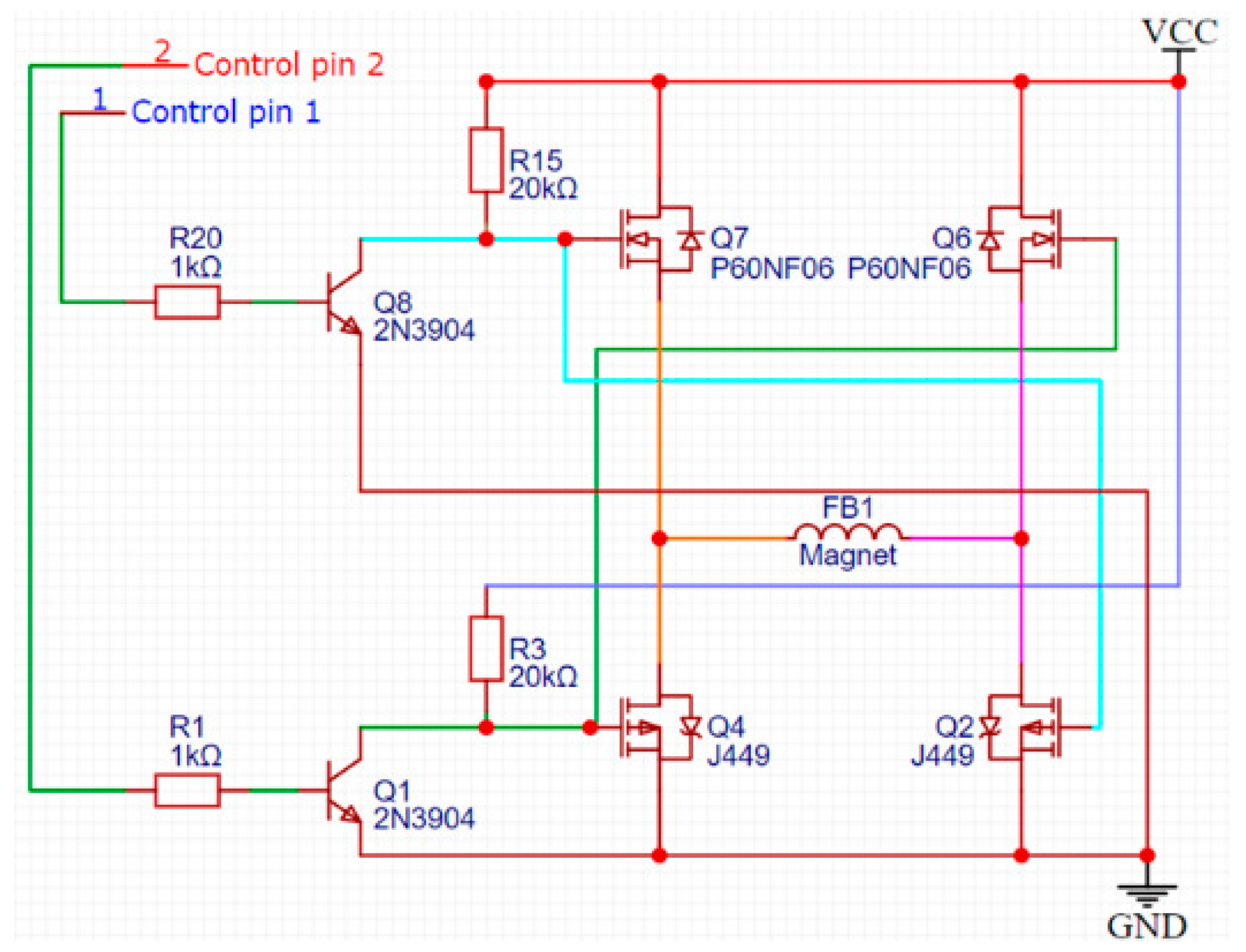

The hybrid AMB control system, like the classical AMB system, consists of three main components: the controller board, the rotor displacement sensor, and the amplifier. The controller board and sensor are similar to those used in the classical AMB system. The amplifier circuit is an H-bridge, which allows the system to change the direction of current flow through the coil.

A conventional H-bridge circuit typically allows the system to change the direction of current flow through a DC motor. In the proposed control system, the DC motor is replaced by an electromagnet. By changing the direction of the current, the axial position of the thrust disk can be controlled. The amplifier system is shown in

Figure 7.

Depending on the rotor’s position, the control signal is output from either Control pin 1 or Control pin 2. This signal then activates the 2N3904 transistor, which in turn controls the P-channel (J449) and N-channel (P60NF06) MOSFETs.

The proportional-integral-differential controller (PID) is used, similarly to the classical AMB, with one main difference. The output of the PID controller has a sign: if the output is positive, the signal is output from Control pin 1; if negative, the signal is output from Control pin 2. The developed amplifier circuit is designed to control both the power supplied to the magnet and the direction of current flow through it (

S9 AMB: Hybrid_AMB_ESP32_control_programm.txt).

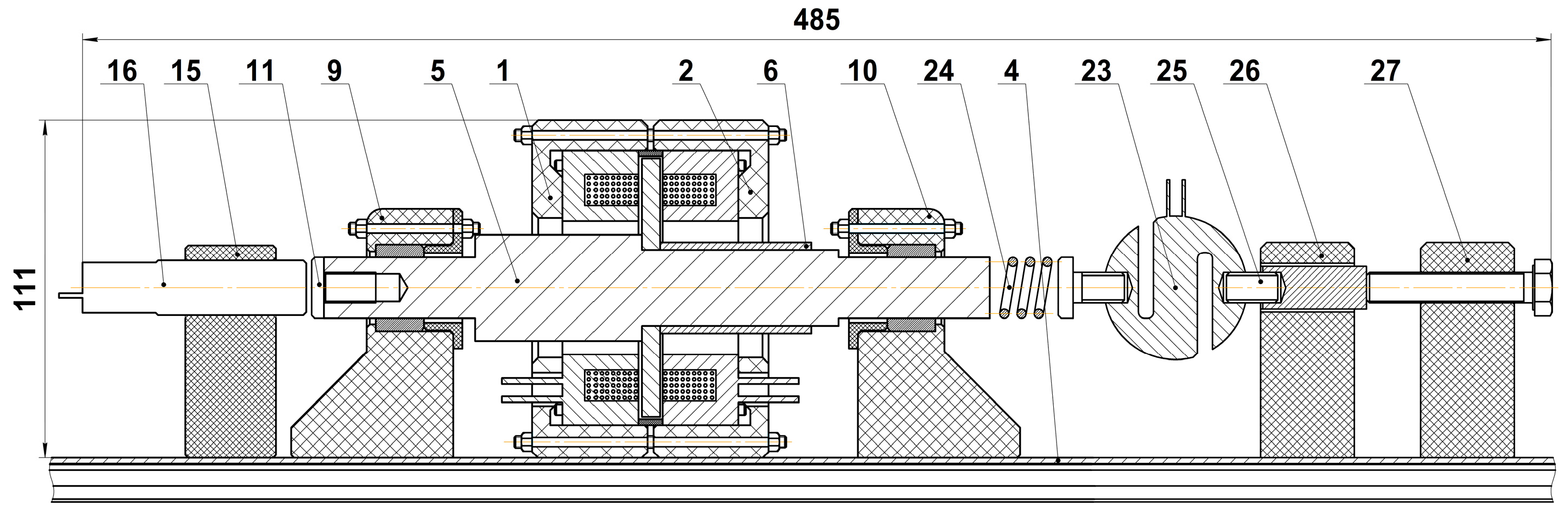

3.3. Design of the Classical AMB Experimental Setup

The initial design was based on analytical calculations, followed by modification of its geometry based on numerical model calculations and fabrication limitations [

66]. The experimental setup was designed (

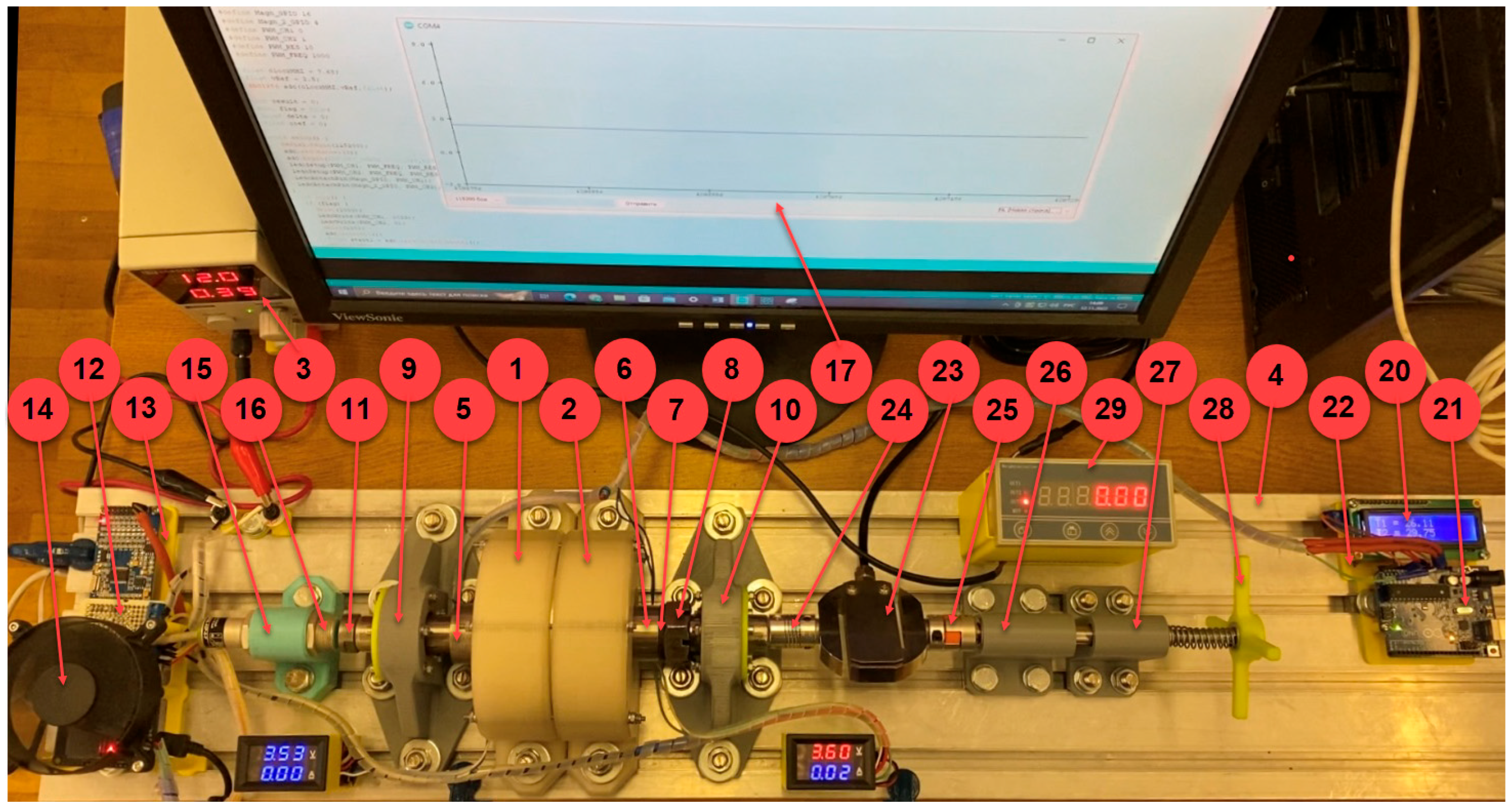

Figure 8), fabricated, and assembled (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) (

S10 Classical_AMB_design.pdf). The setup consists of three components: the axial electromagnetic bearing (actuator), the control system, and the mechanical system for applying external axial force.

The actuator consists of two axial electromagnets mounted in housings 1 and 2, powered by a power supply 3. Housings 1 and 2 are fixed to the T-slot base 4. An aluminum spacer ring maintains a gap of 1 mm between the thrust disk and the electromagnets. This disk is mounted on shaft 5 and is fixed by a bushing 6, a washer 7, and a nut 8. Shaft 5 is supported by two axial bushings mounted in supports 9 and 10. The shaft is made of stainless steel (12H18N10T). A screw 11, made of structural steel 40, provides a clear signal from the displacement sensor. The circuit board 12, which houses the ESP32 microcontroller, the ADC, and the transistors with heat sinks, is mounted inside housing 13 and cooled by a fan 14. The axial displacement sensor 16 is installed in housing 15. Ammeters and voltmeters 18 and 19 are installed to measure the coil’s voltage and current. Two B57164-K thermistors are connected to the coils to monitor their temperature, using the Arduino board 21, housing 22, and LCD display 20. Data are displayed on screen 17 (

S11 Temperature_measurements_Arduino_program.txt).

The mechanical system for applying external axial force consists of an S-shaped strain gauge 23 (DYLY-102S), to which a spring coupling 24 is attached. On the opposite side of sensor 23, coupling 25 is connected to transmit the axial force from the rod mounted in housing 26. The axial force on the rod is applied via a screw mounted in the housing 27, which is rotated by the handle 28.

3.4. Design of the Hybrid AMB Experimental Setup

The initial design of the hybrid AMB was based on analytical calculations, followed by adjustments of its geometry based on numerical model calculations [

67]. The simplified axial hybrid AMB design is shown in

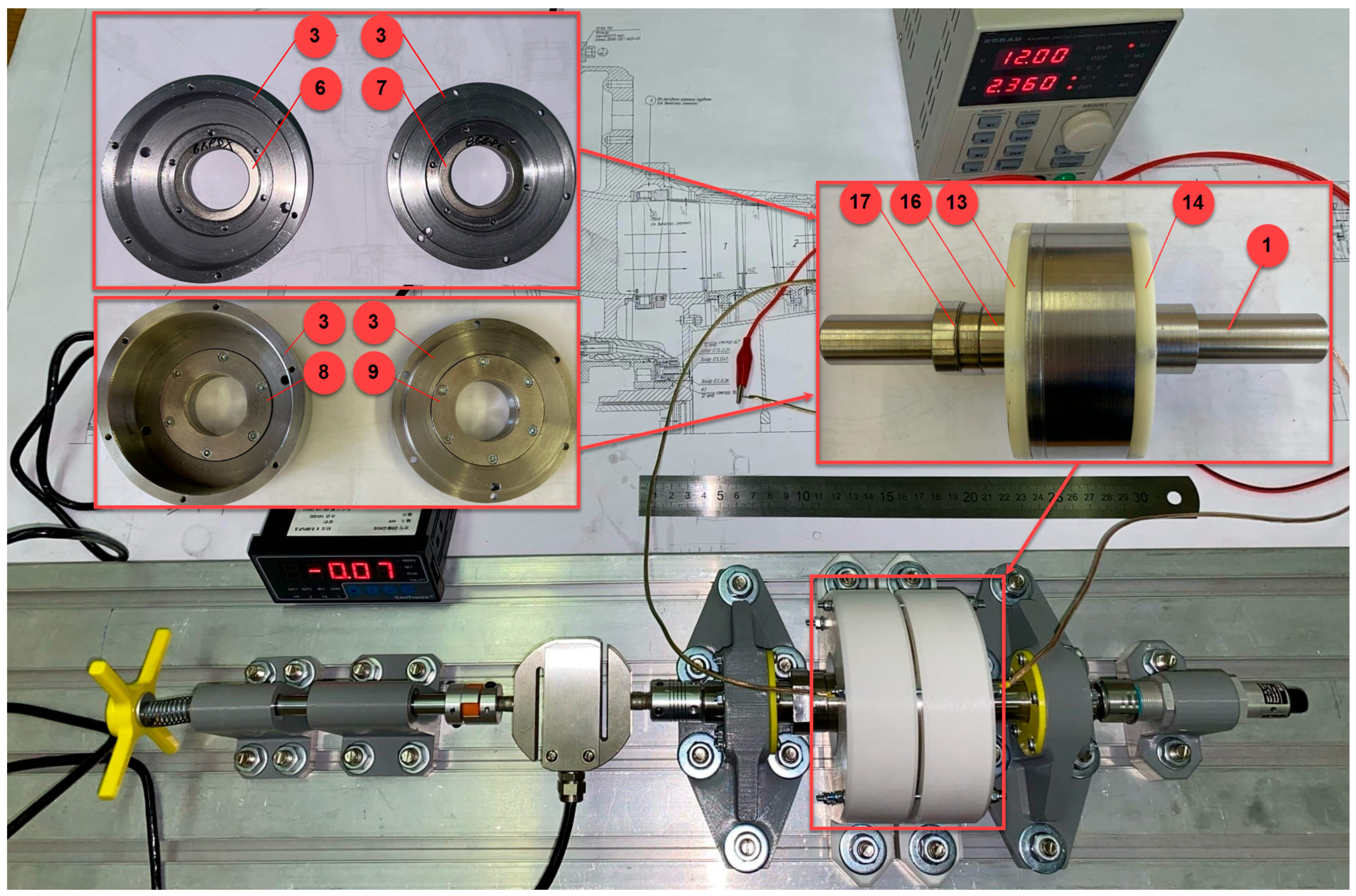

Figure 11 (

S12 Hybrid_AMB_design.pdf). The rotor consists of a shaft 1 and a ferromagnetic disk 2. The stator includes a magnetic core 3, a coil 4 wound with wire 5, and clamping rings 13 and 14 used to secure the magnetic core parts. The PM rings 6 and 7 are fixed using holders 8 and 9. Air gaps—radial (15) and axial (10, 11)—are maintained between the stator and rotor.

The magnetic conductors 3 are made of soft magnetic material 10880. The coil 4 is made of the diamagnetic, dielectric material polyamide-6. The permanent magnet holder 8 is made of stainless steel and was later replaced by holders made from diamagnetic, dielectric polyamide-6. Both the magnetic core 3 and the PM holders 8 and 9 are split into two radial segments, with the insulating pads 12 between them. These insulating pads reduce path contours to minimize the negative influence of eddy currents. The segmented magnetic core 3 is fixed by clamping rings 13 and 14, which are made of polyamide-6. The ferromagnetic disk 2 is secured by the hub 16 and the nut 17. The setup was designed, fabricated, and assembled (

Figure 12).

The hybrid AMB working principle is based on double-sided attraction forces acting on the thrust disk. When displacement of the ferromagnetic disk 2 is detected, the control system adjusts the current in the coil 5. This adjustment changes the magnetic attraction force, restoring the rotor to its equilibrium position. In the developed axial hybrid AMB, the bias magnetic flux is generated by PMs 6 and 7.

It should be noted that the alternating magnetic field, caused by the current change in the coil and rotor oscillations, induces eddy currents. According to the Joule–Lenz law, these eddy currents cause heating of the conductors, leading to increased energy losses in the magnetic conductors. This, in turn, reduces the efficiency of the bearing. Additionally, the magnetic fields caused by eddy currents in the circular ferromagnetic parts of the bearing prevent the controlling magnetic flux from changing. As the frequency of the control current increases, the magnetizing force of the eddy currents reduces the depth of magnetic field penetration. This results in a reduced effective cross-sectional area of the magnetic core, decreasing its magnetic permeability and weakening the magnetic field.

Eddy currents lead to a decrease in the adjustment frequency of the control current, which in turn reduces the bearing’s dynamic stiffness. This issue is particularly detrimental to the permanent magnet bias bearing design, due to its relatively low stiffness and damping characteristics compared to the classical AMB design. Therefore, the magnetic core was designed to be split, similarly to the segmented classical AMBs [

35,

36,

37].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Classical AMB Results

The initial data for the analytical calculation are presented in

Table 2. During the development of the experimental setup, adjustments were made to the actuator’s geometric parameters. These adjustments included reducing the outer diameter and thickness of the thrust disk to fit the aluminum spacer ring, which had already been fabricated. The analytical and numerical results for both the initial and fabricated geometric parameters are shown in

Table 3.

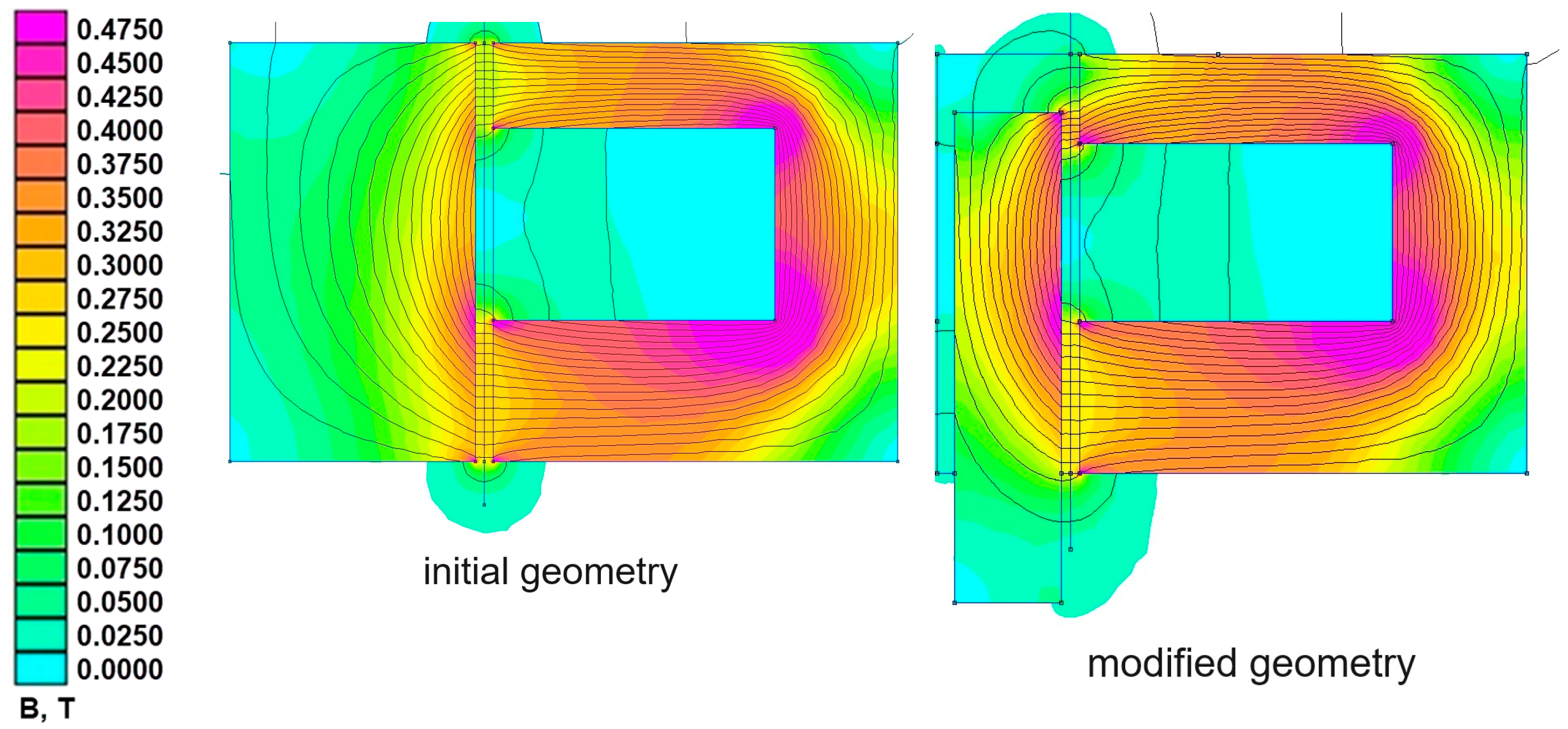

According to the numerical results for the initial geometry, obtained through analytical calculations, the load-carrying capacity at a current of 2.4 A (with power consumption of 17.87 W) is 71.8 N, with an air gap of 1 mm. The difference between the analytical and numerical results is less than 10%. The coil temperature reaches 143.9 °C (416.9 K), which is lower than the maximum permissible temperature of the insulation material (180 °C). The distribution of magnetic flux density in the AMB for the two geometry variants is shown in

Figure 13. The flux density for the initial geometry is more evenly distributed.

The graph in

Figure 14 shows the distribution of magnetic flux density in the radial direction in the middle of the gap for both the initial and modified geometries. The flux density for the initial geometry is more evenly distributed.

According to

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, the initial geometry demonstrates lower flux density both in the stator and in the gap (the flux density at the outer pole is lower by 0.09 T). The initial geometry also provides a higher bearing capacity compared to the modified geometry. The coil temperature reaches 445.8 K (172.8 °C), which is close to the maximum permissible insulation material temperature. Although the modified geometry of the AMB performs worse than the initial one, this part of the work aimed to validate the numerical models and confirm the overall approach in designing the test rig, which will then be implemented for the hybrid AMB. Therefore, achieving high performance was not a target of this work.

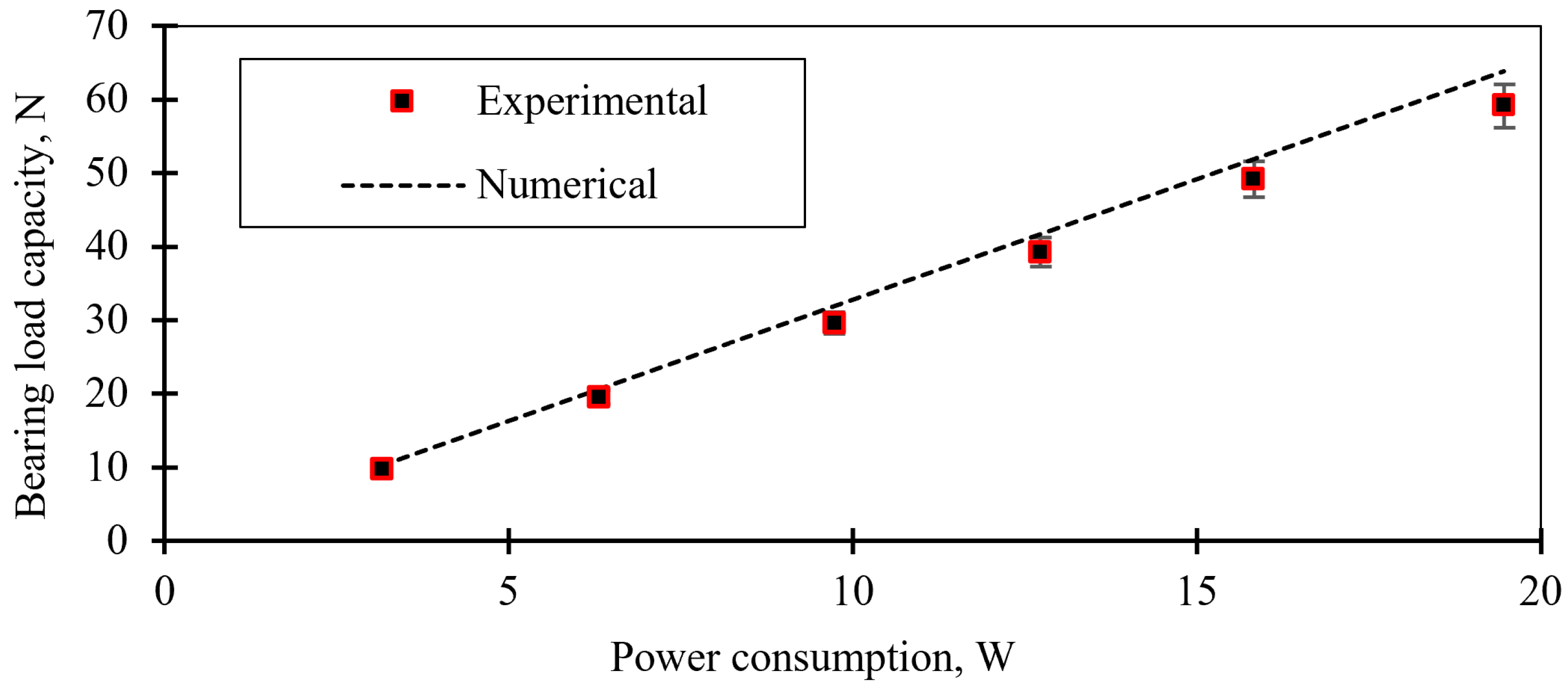

The experiment was conducted. The bearing load capacity dependence on power consumption is shown in

Figure 15. For each step, the load was held for 5 s.

It was found that the difference between the numerical model calculations and the experimental data for the bearing load capacity did not exceed 8%. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that the FEMM 4.2 software does not account for eddy currents generated by rotor motion. This limitation also explains the increasing difference between the experimental data and the calculation results as the external load increases. As the external load increases, the system raises the current in the electromagnet coil, which enhances the negative effects of eddy currents. Additionally, fabrication errors in the plastic electromagnet housing could also contribute to this discrepancy.

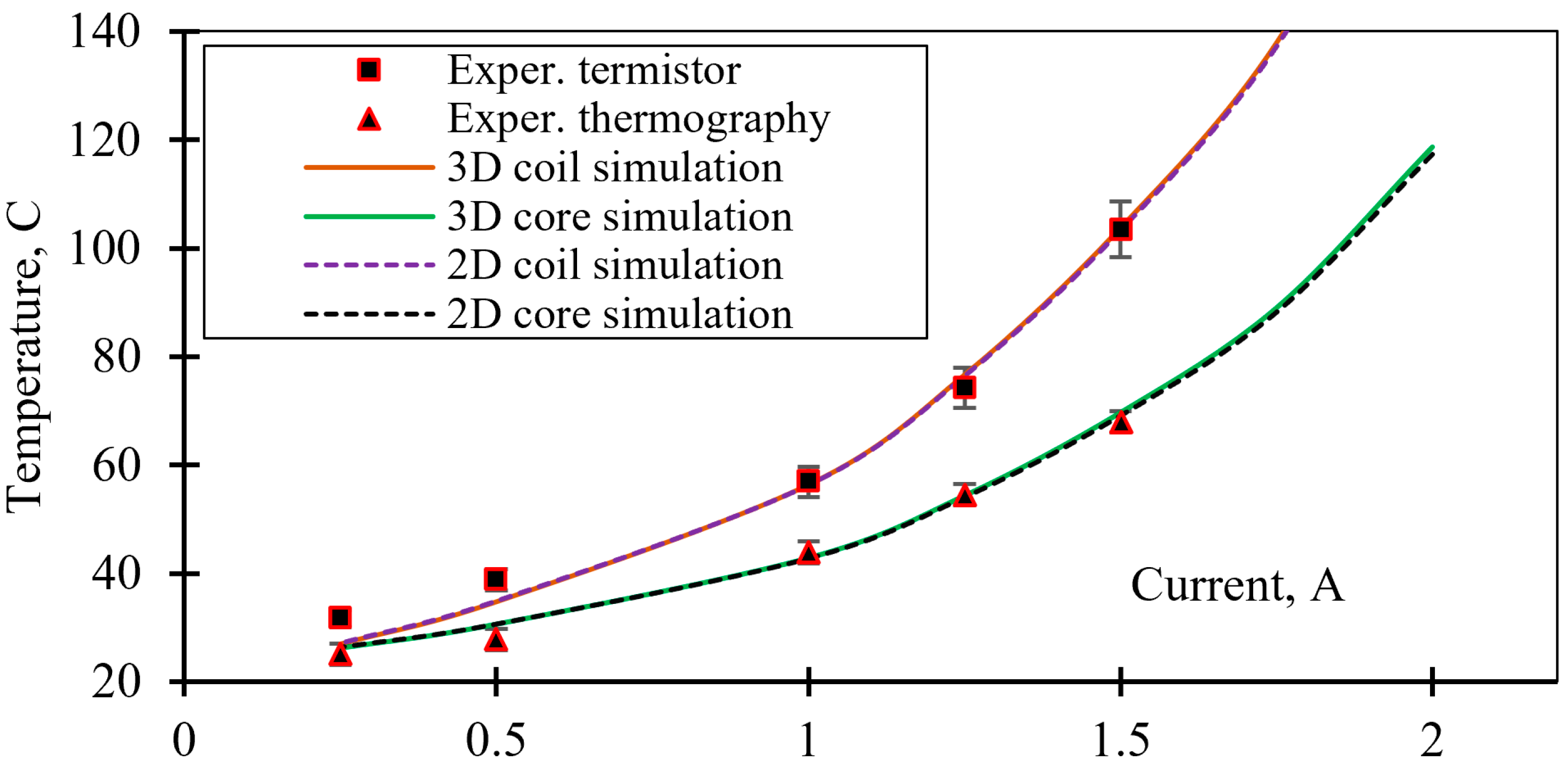

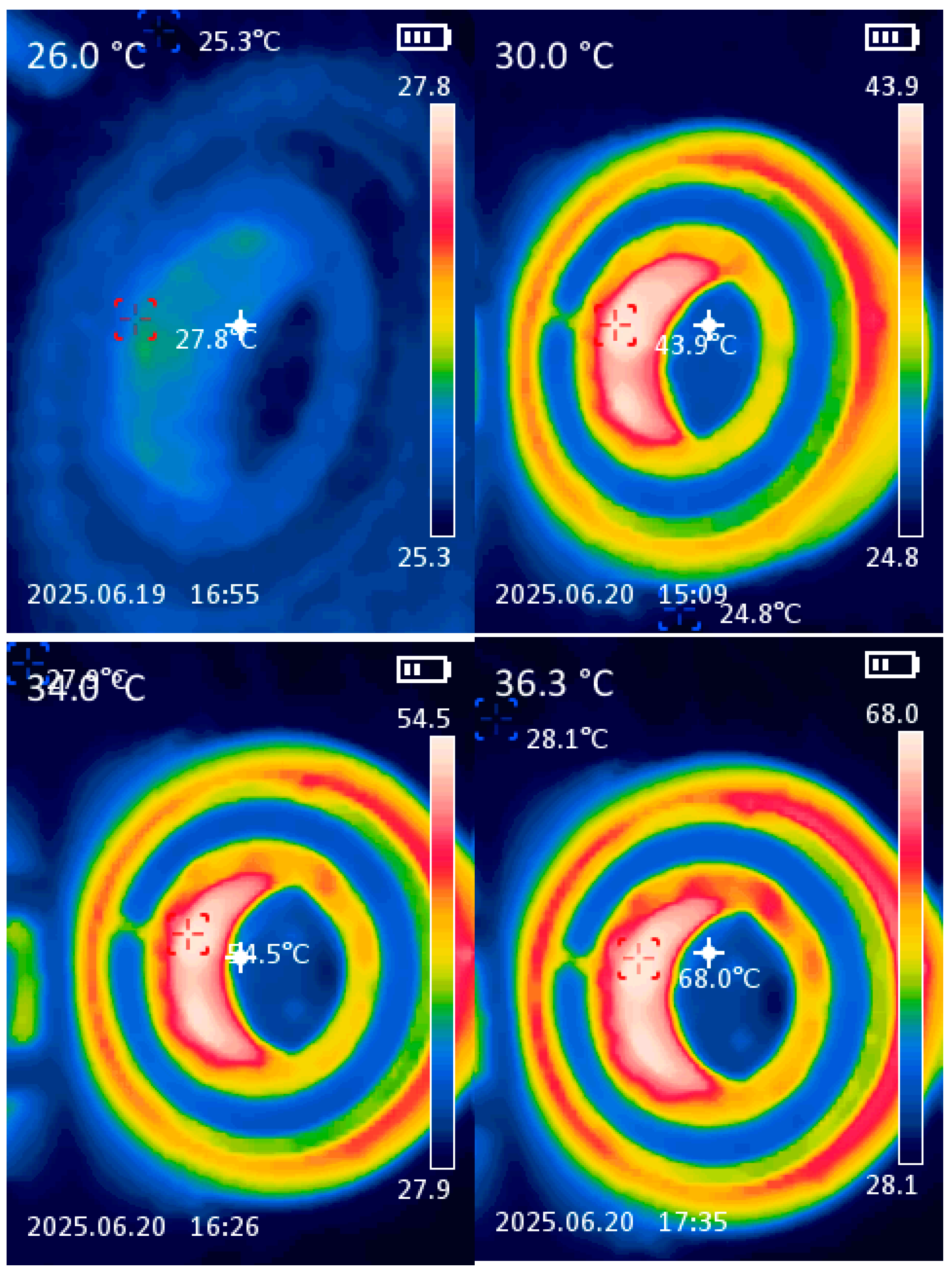

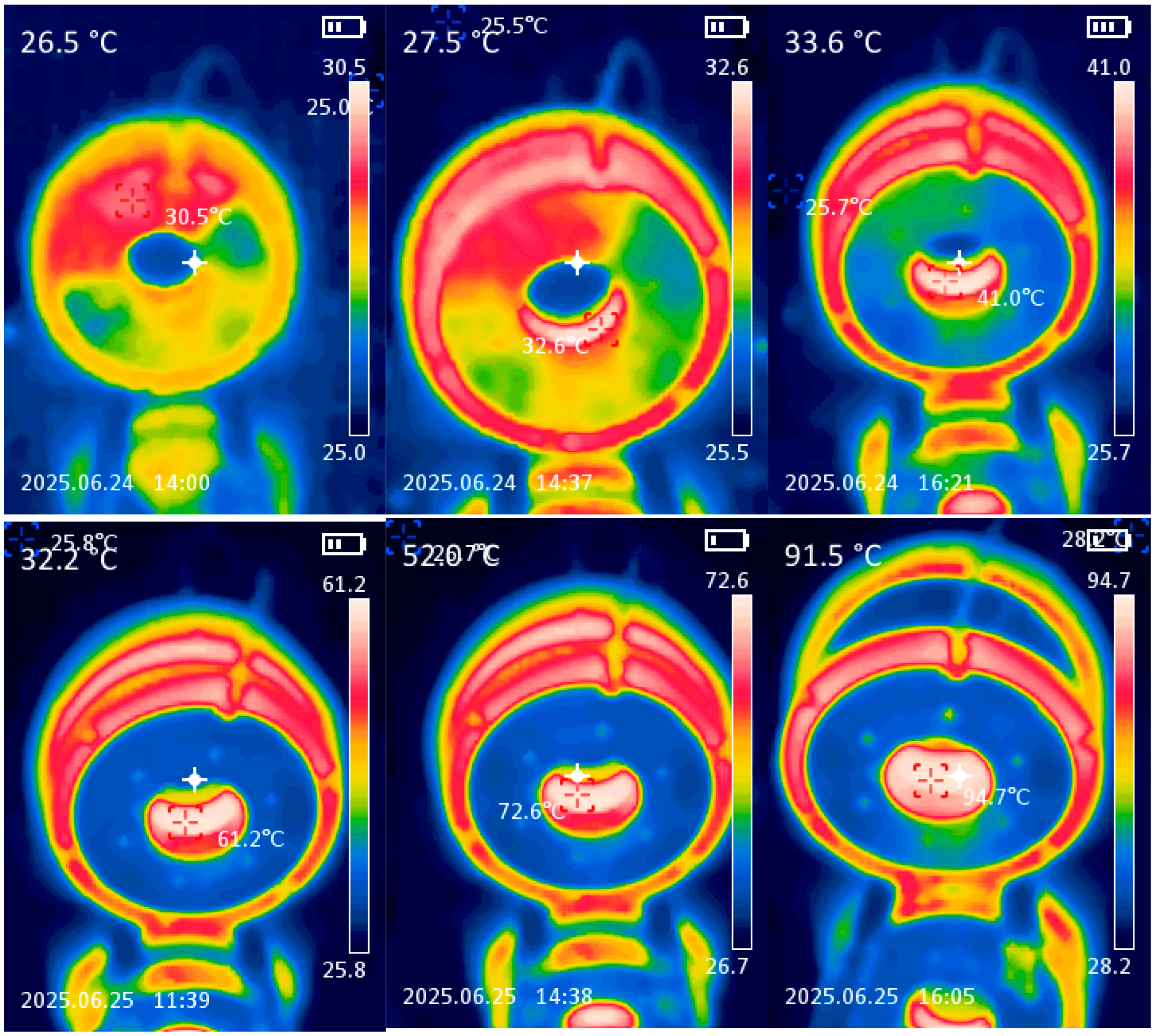

Figure 16 shows the coil and magnetic core temperature dependences on current. The coil temperature was measured by a thermistor. The temperature distribution of the electromagnet face was measured by infrared thermography (

Figure 17). The emissivity coefficient was set to ε = 0.85, which corresponds to the rough surface of the magnetic material 10880. The surfaces were not coated, painted, or polished and had small oxidation marks, with an average roughness of Ra 6.3. The cold area between the electromagnet’s inner and outer poles corresponded to the aluminum bobbin, requiring a coefficient of about ε = 0.15.

Two thermal models (2D and 3D) were used to determine the temperature distribution in the AMB. The 3D model of the electromagnet consists of 86,325 elements, with the equivalent coil element size set to 0.2 mm. While the 2D model consists of 14,084 elements, using the same coil element size. For each step, the current was held until the coil temperature remained steady for 5 min (it took more than 1 h for each step). Both 2D (

Figure 18) and 3D (

Figure 19) numerical models provided accurate results (the difference is less than 0.4%). The difference between the 3D model results and the experimental data did not exceed 3.3% for the coil temperature and 2.5% for the magnetic core at temperatures above 40 °C (

Figure 16).

The experimental data agree well with numerical models, confirming the feasibility of a simplified digital AMB controller based on chip components. Although it lacks filters and safety devices, it provides the required performance. A further improved version could reduce the AMB control cost. It is also suitable for educational purposes.

4.2. Hybrid AMB Results

Table 4 presents the initial data for the analytical model. For the hybrid AMB, the coil wire diameter was determined by specifying the current density as an input parameter. As a result of the analytical model calculation, the geometry of the magnetic core and coil parameters was determined, as well as the coil temperature at the maximum current.

The numerical model was developed and calculated using, as initial data, the parameters obtained from the analytical model. Then, the geometry adjustments were made during fabrication. The analytical and numerical results for the initial and fabricated geometric parameters are shown in

Table 5. The difference between the two diameters (the classical AMB coil has 0.511 mm wire, while the hybrid AMB has 0.6 mm) comes from different design approaches: in terms of the classical AMB, it was a practical approach (this wire was already available) while a current density-based approach was used for the hybrid AMB.

The temperature difference of 8.95 K between the analytical and numerical models is caused by the reduction of the coil wire diameter from 0.617 to 0.6 mm to fit the required number of coil turns within the slot volume. The calculation results for the hybrid axial AMB, with a maximum current of 2.4 A and 1 mm gap, show a total power consumption of 14.49 W. The load-carrying capacity of the bearing at a current of 2.4 A is 93.3 N.

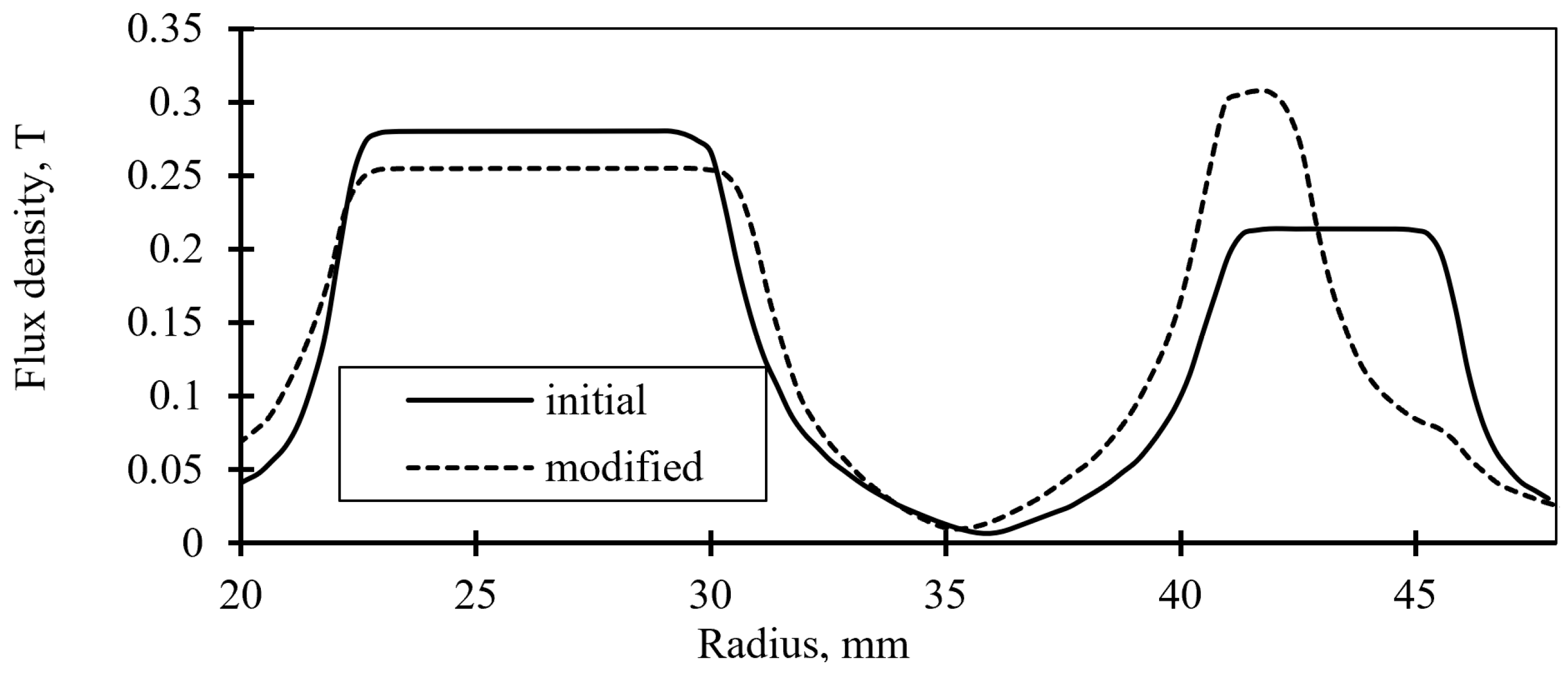

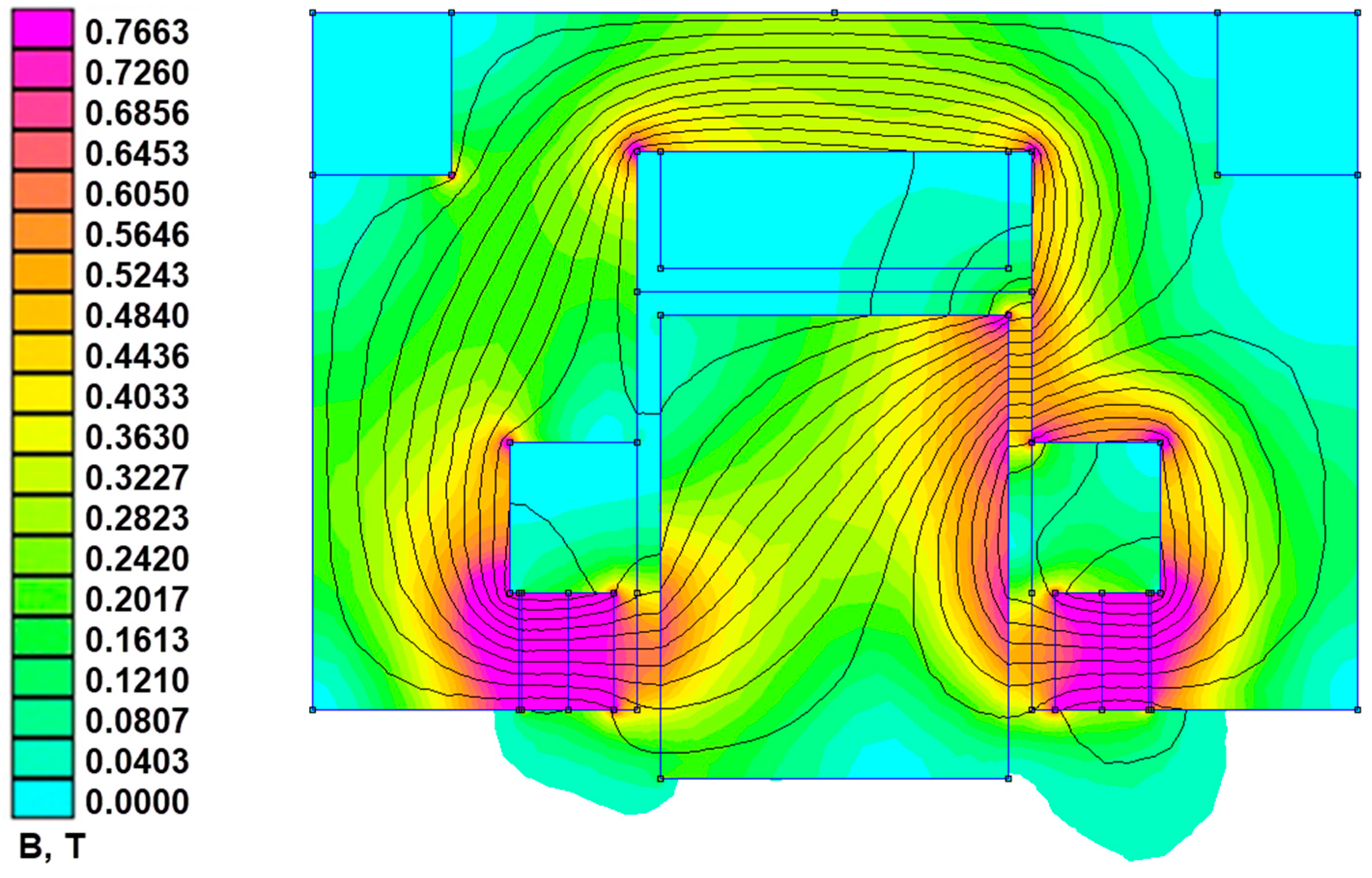

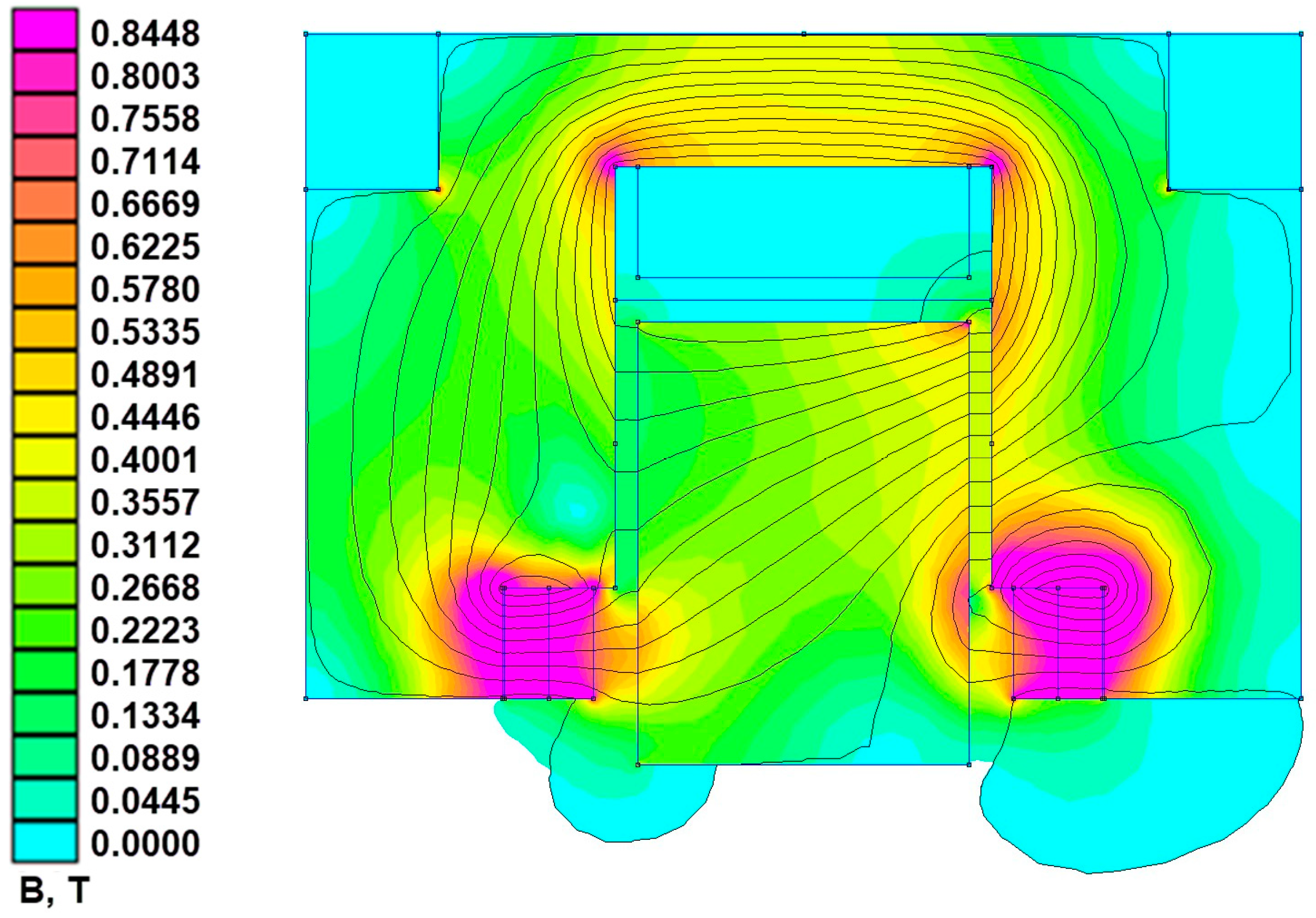

The distribution of the magnetic flux density in the hybrid AMB is shown in

Figure 20. The external force (left to right) balances the attraction force pulling the disc towards the left permanent magnet. Due to the annular grooves in the magnetic core 3, in which the diamagnetic holders of the permanent magnets 8 and 9 are installed, the magnetic flux lines of the permanent magnets 6 and 7 pass through these magnets and form a closed loop around their holders. As a result, the magnetic fields of the permanent magnets 8 and 9 are redistributed over a larger diameter. Thus, the enlarged interaction area between the magnetic fields of the permanent magnets and the electromagnet increases the attraction force on disc 2, enhancing the load capacity.

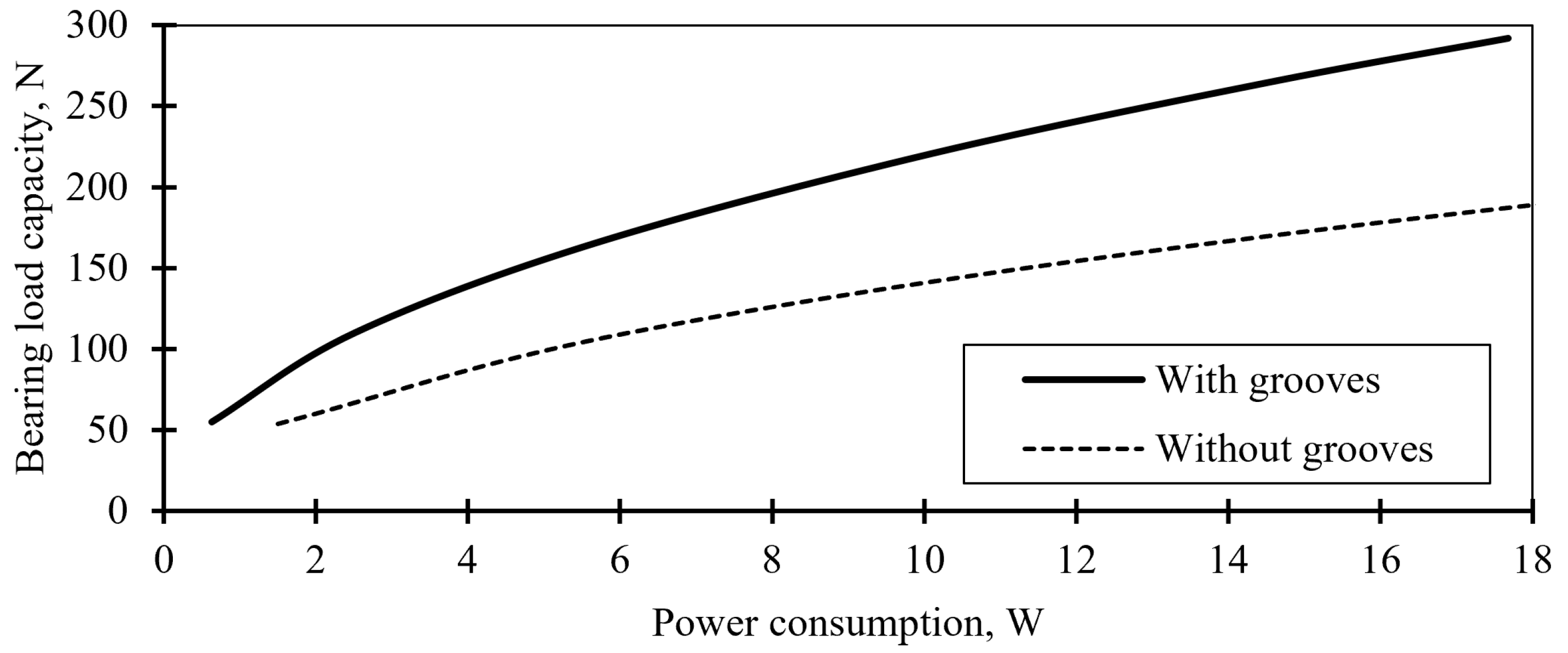

In the hybrid AMB with grooves, the load capacity increases by 44.2%, reaching 93.3 N, compared to 64.7 N in the design without grooves (

Figure 21).

Figure 22 shows the load-carrying capacity dependence of the hybrid axial AMB on the required electrical power consumption for two different designs: with grooves and without. This dependence was calculated for an axial air gap of 0.5 mm between the thrust disc and the magnetic core, a typical value for axial AMB systems with a similar outer diameter.

The presence of grooves allows for the convenient placement and securing of permanent magnets relative to the magnetic core, thus simplifying assembly and ensuring their proper alignment within the core.

Figure 23 and

Figure 24 show a comparison of the load capacity dependence on electrical power consumption for both hybrid and classical AMBs, with an axial air gap of 0.5 mm and 1 mm, respectively. The initial geometric parameters of the classical AMB (

Table 3) are used for the comparative evaluation. The bias current for the classical AMB was set to 1.2 A (half of the maximum current of 2.4 A).

The load capacity at nominal operating mode with an air gap of 0.5 mm is 150 N. In maximum operating mode, the load capacity reaches 270 N. The power consumption of the classical AMB is 11.64 W in nominal operating mode. In contrast, the hybrid AMB requires only 4.63 W under the same conditions, resulting in a 60.2% improvement in efficiency. In the maximum operating mode, the classical AMB requires 17.78 W, while the hybrid AMB requires 15.11 W, resulting in a 15.02% efficiency improvement for the hybrid bearing.

For an air gap of 1 mm and a bearing load capacity of 60 N, the classical AMB requires 15.18 W, while the hybrid AMB requires 5.97 W, resulting in a 60.67% efficiency improvement for the hybrid bearing. Depending on the application, operating mode, required load capacity, and dimensional constraints of the housing, the power consumption efficiency of the hybrid AMB can vary significantly compared to that of the classical axial AMB.

In the hybrid bearing, the use of permanent magnets eliminates the need for an additional copper coil, thereby reducing the required length of the magnetic core. For the magnet geometry considered, the length of the hybrid bearing is reduced by 13.2 mm compared to the classical bearing, and the maximum outer diameter is reduced by 1.5 mm. But the actuator mass has remained virtually unchanged (reduction of only 50 g). However, the overall weight of the system can be reduced due to the decrease in required power consumption.

Stable operation of the hybrid AMB with the proposed control system has not yet been achieved, due to the strong nonlinearity introduced by the permanent-magnet bias. In addition, the limited current-loop bandwidth and chosen sensor noise reduce control robustness. The design of the control system for the hybrid AMB requires further improvements and implementation of more advanced nonlinear control strategies.

That is why only a static test has been conducted, where the thrust disk is attached to one of the AMB poles with PM. Then, by supplying current to the coil, the axial force is steadily increased until the separation of the thrust disk and the magnet core pole. It was discovered that the stainless-steel holders used to secure the permanent magnets 8 and 9 negatively affected the performance. These holders were subsequently replaced with polyamide-6 versions.

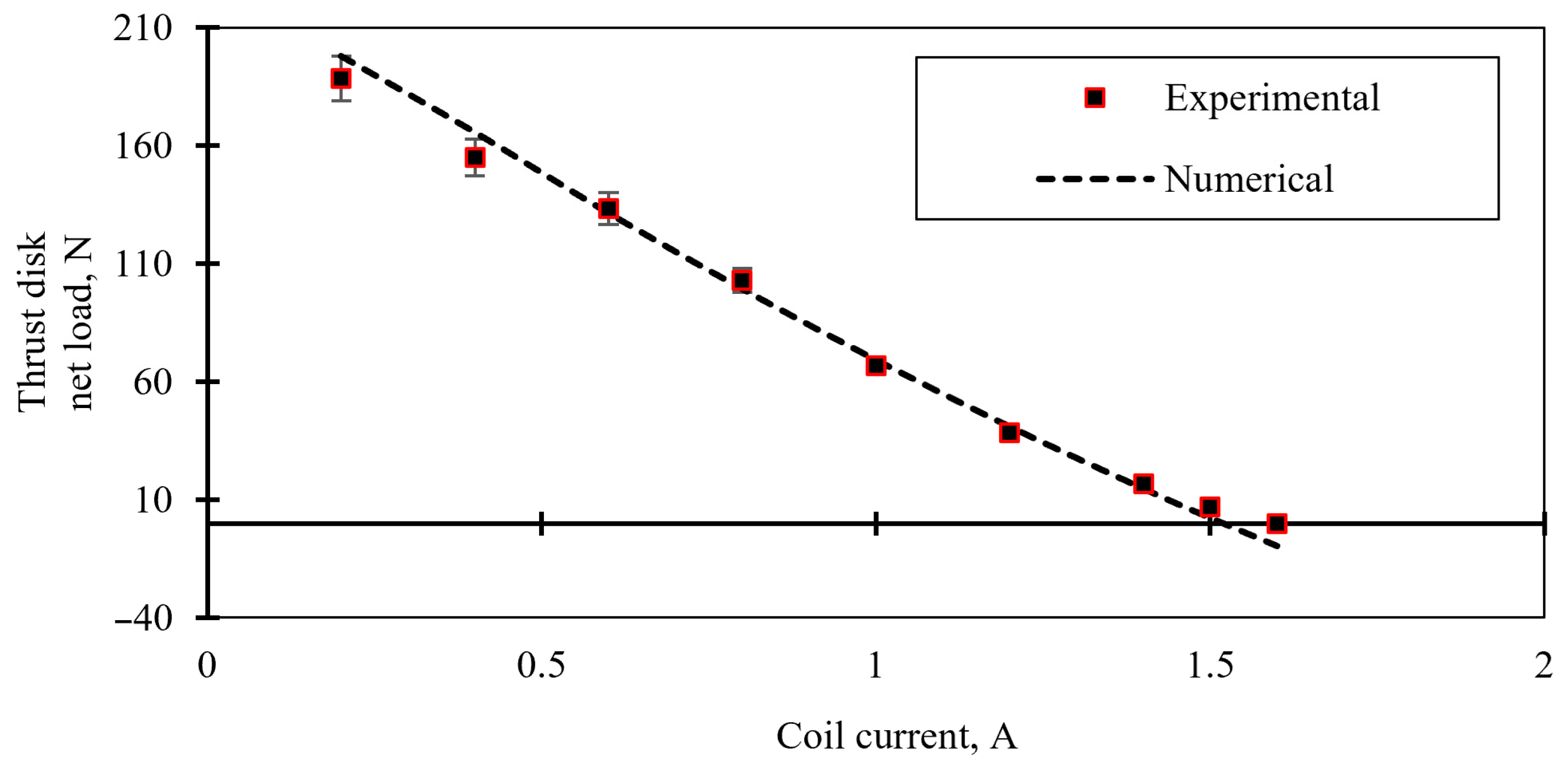

The experimental net load required for thrust disk separation was recorded and compared with simulation results (

Figure 25) for the polyamide-6 version holders.

The simulation results show good agreement with the experimental data. The difference between the experimental and simulation results did not exceed 7% for coil current ranging from 0.2 to 1.4 A.

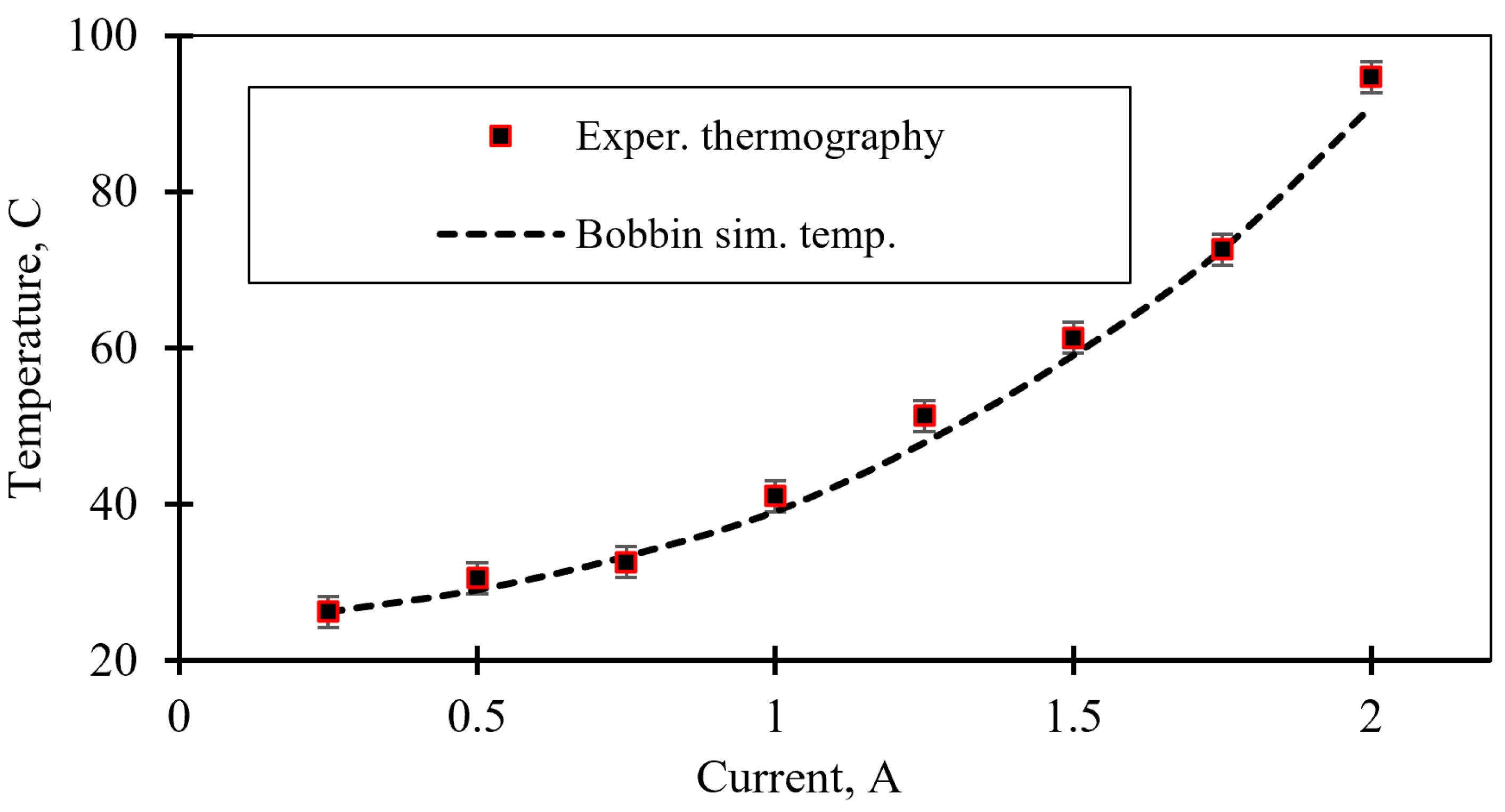

Figure 26 shows the bobbin temperature dependence on the coil current. The temperature distribution of the electromagnet face (including the bobbin inner surface) was measured by infrared thermography (

Figure 27). For each step, the current was held until the coil temperature stabilized for 5 min (it took more than 1 h for each step to reach a steady-state value).

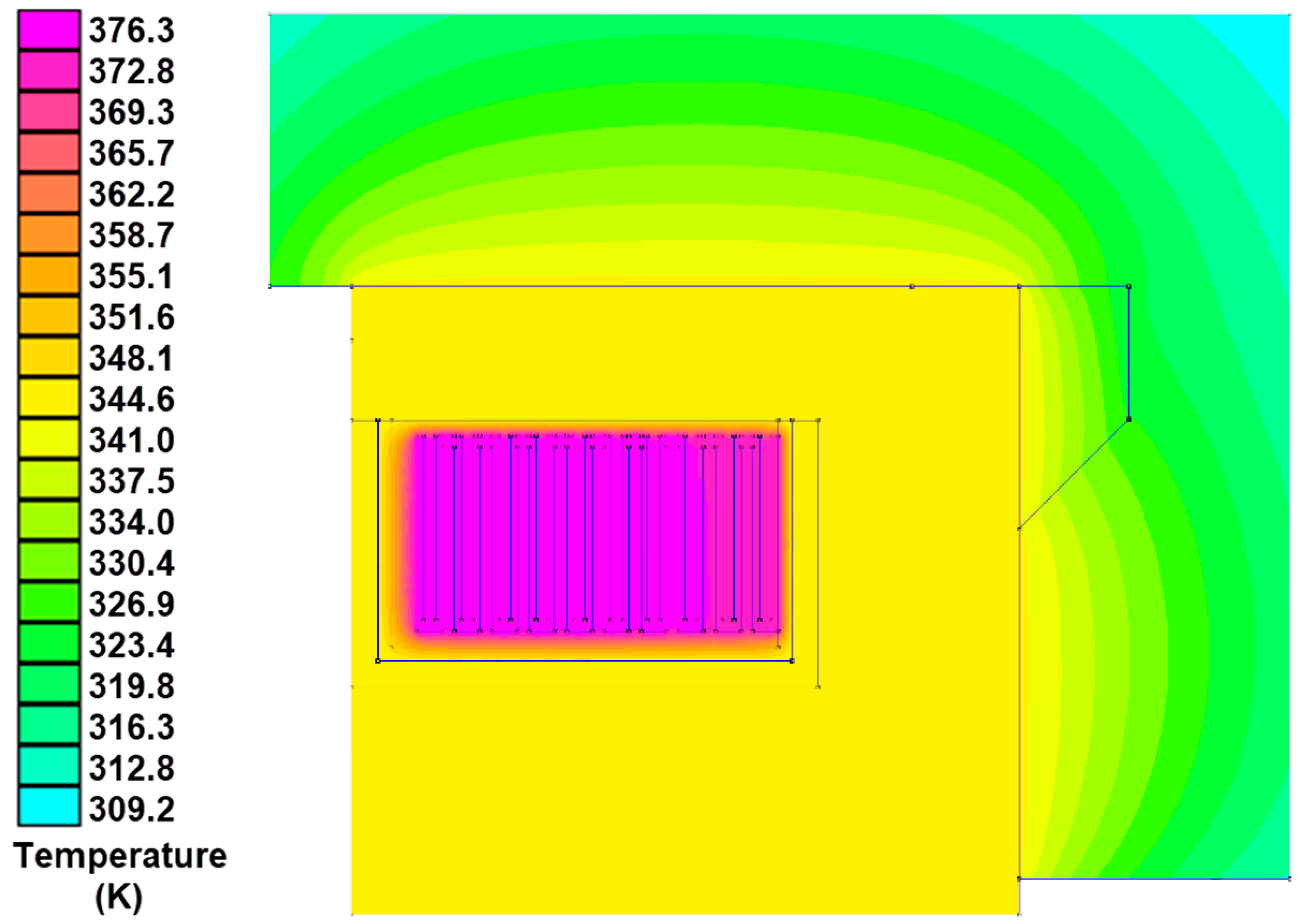

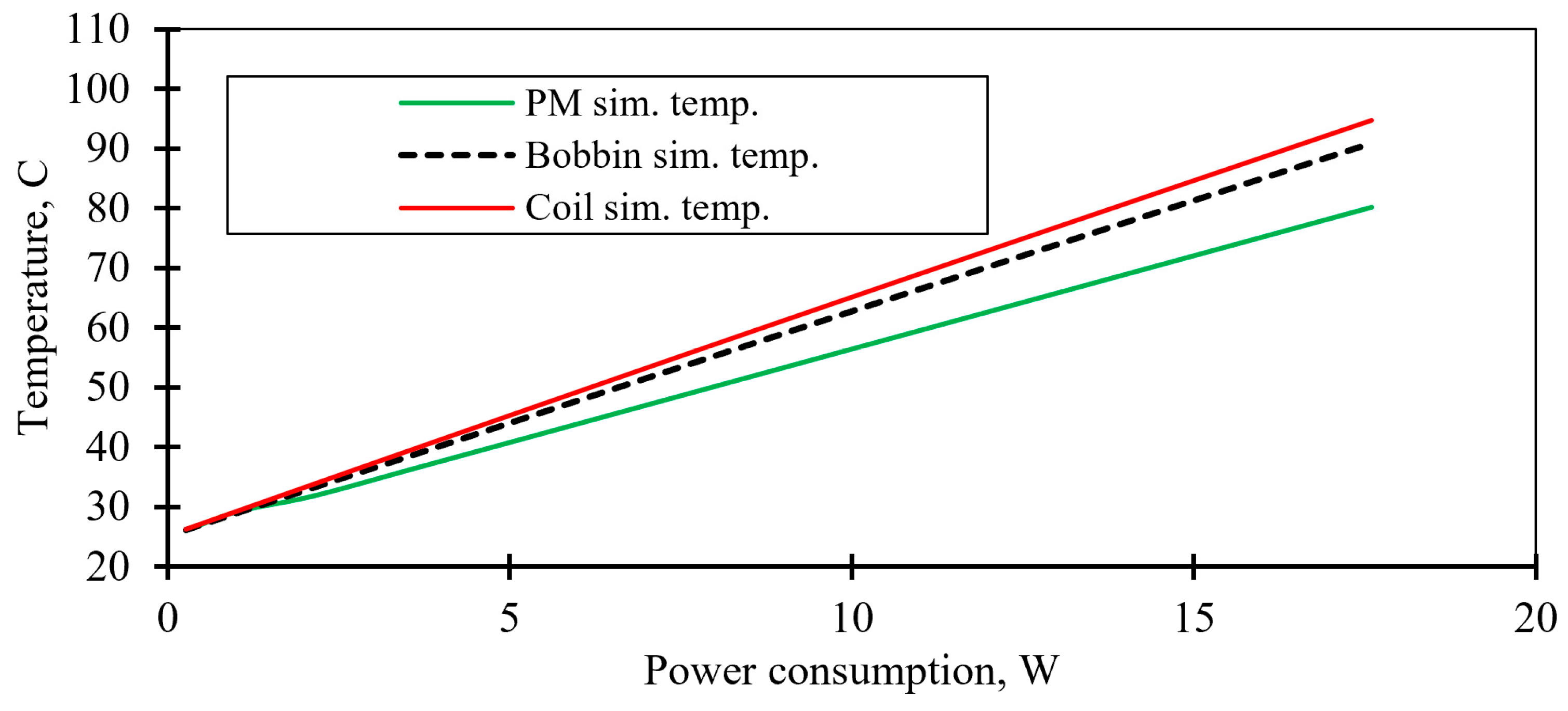

A 2D thermal model was used to determine the temperature distribution in the AMB. Equivalent coil modeling was used, with a similar volume and external surface area of the wire. The bobbin, PM, and coil temperature dependencies on the power consumption have been determined (

Figure 28).

The difference between the 2D model results and experimental data did not exceed 6.8% for the bobbin temperature, which has the highest outer surface temperature, according to both thermography and simulation results (

Figure 29).

The coil temperature of the hybrid AMB did not exceed 367.8 K (94.8 °C) at a current of 2 A. In contrast, for the classical AMB with the same bearing load capacity and power consumption, the coil temperature was about 198.3 °C. The temperature of the permanent magnets in the hybrid AMB was 80.18 °C, which is below the maximum temperature limit for the N38H alloy of 120 °C.

It should be noted that under the studied operation conditions, with a maximum obtained temperature of 80.18 C for a 2 A coil current, the maximum opposing field of 27 kA/m was obtained for the PM. The field intensity was lower than the temperature-reduced coercivity of about 687 kA/m. This prevented the permanent magnet demagnetization under the studied conditions. However, it is necessary to evaluate the demagnetization risk for PM-biased AMBs in terms of more extreme operation conditions [

68].

The proposed permanent magnet bias AMB offers several advantages over the classical axial AMB design in terms of power consumption and, consequently, reduced temperatures and heat flow, which is beneficial for turbomachinery applications. An additional benefit of the proposed design is the relatively distant placement of the PM from the coil to reduce the PM temperatures; thus, it allows room for further improvements. However, the PM-bias AMB requires more complex and advanced controllers [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

5. Conclusions

The proposed design of the hybrid axial active magnetic bearing (AMB) with permanent magnet biasing (PM-biased) offers substantial advantages over the classical AMB design, particularly in terms of reduced power consumption and lower heat generation, which is important for turbomachinery and aviation applications.

The use of the PM eliminates the need for additional electric power consumption to generate the bias magnetic flux, resulting in a more than 60% reduction in power consumption compared to the classical AMB design (for a 150 N load-carrying capacity with a 0.5 mm gap or a 60 N load-carrying capacity with a 1 mm gap). The discrepancy between numerical and experimental results did not exceed 8% for load capacity.

According to thermal analysis, the coil temperature of the PM-biased bearing does not exceed 94.8 °C, whereas the classical AMB’s coil temperature reaches 198.3 °C under the same load-carrying capacity. The permanent magnet temperature remains below 80.18 °C, which is lower than the maximum permissible temperature for the N38H alloy (120 °C). Finite-element axisymmetric models of both classical and hybrid axial AMBs provide accurate temperature distributions. The discrepancy between numerical and experimental results did not exceed 6.8%.

An additional advantage of the proposed design is the remote placement of the permanent magnets from the coil (the primary heat source), which allows for further hybrid AMB performance improvements.

The developed control system, based on the ESP32 microcontroller, demonstrates the feasibility of using low-cost components for a digital AMB controller. However, stable operation of the hybrid AMB with the proposed control system has not yet been achieved due to strong nonlinearity caused by permanent magnets. The reported superior performance of the hybrid axial AMB, including low power consumption and low temperature rise, is based solely on the static tests and simulation results.