Temperature Estimation of Thin Shape Memory Alloy Springs in a Small-Scale Hip Exoskeleton with System Identification and Adaptive Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

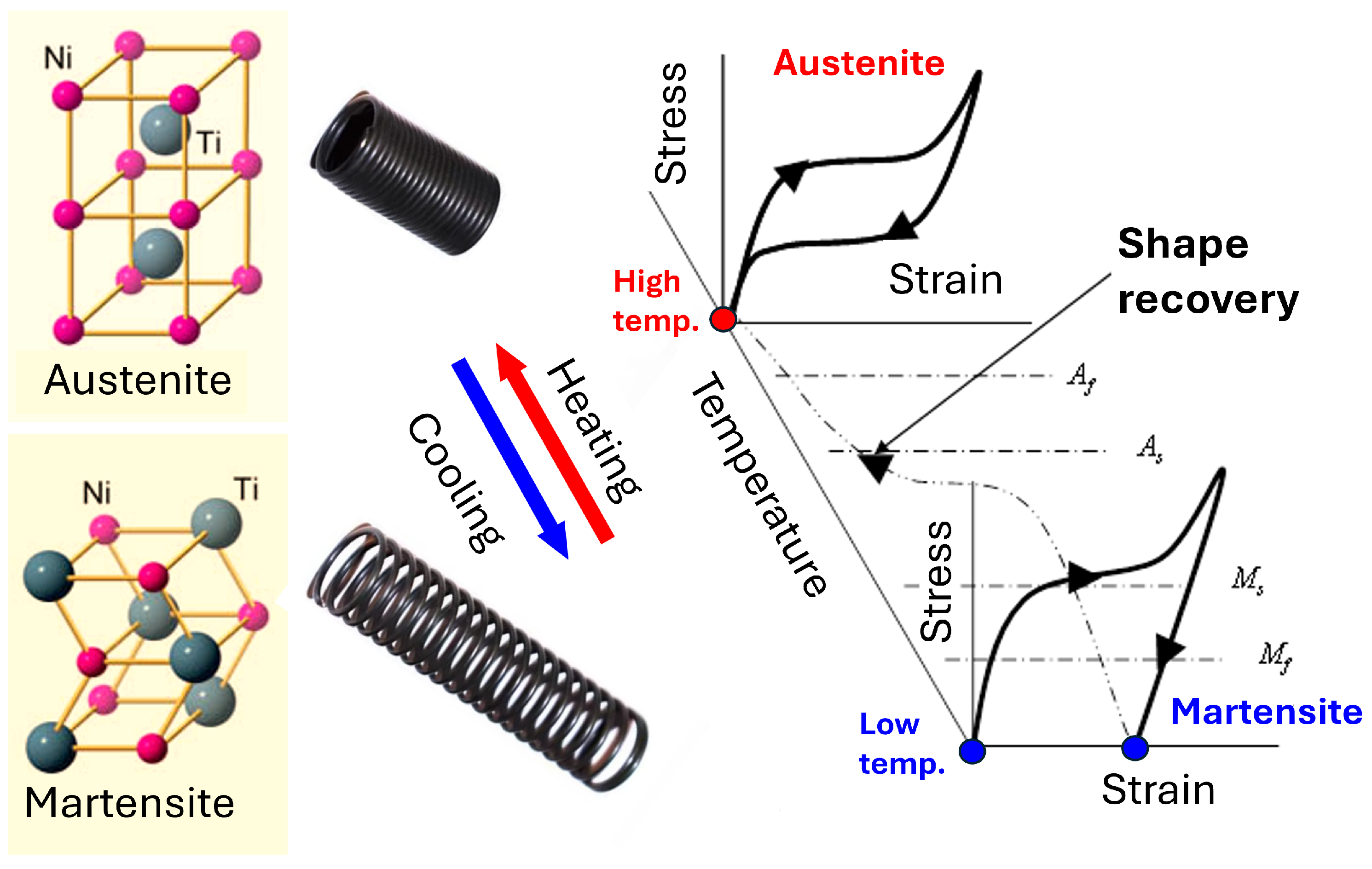

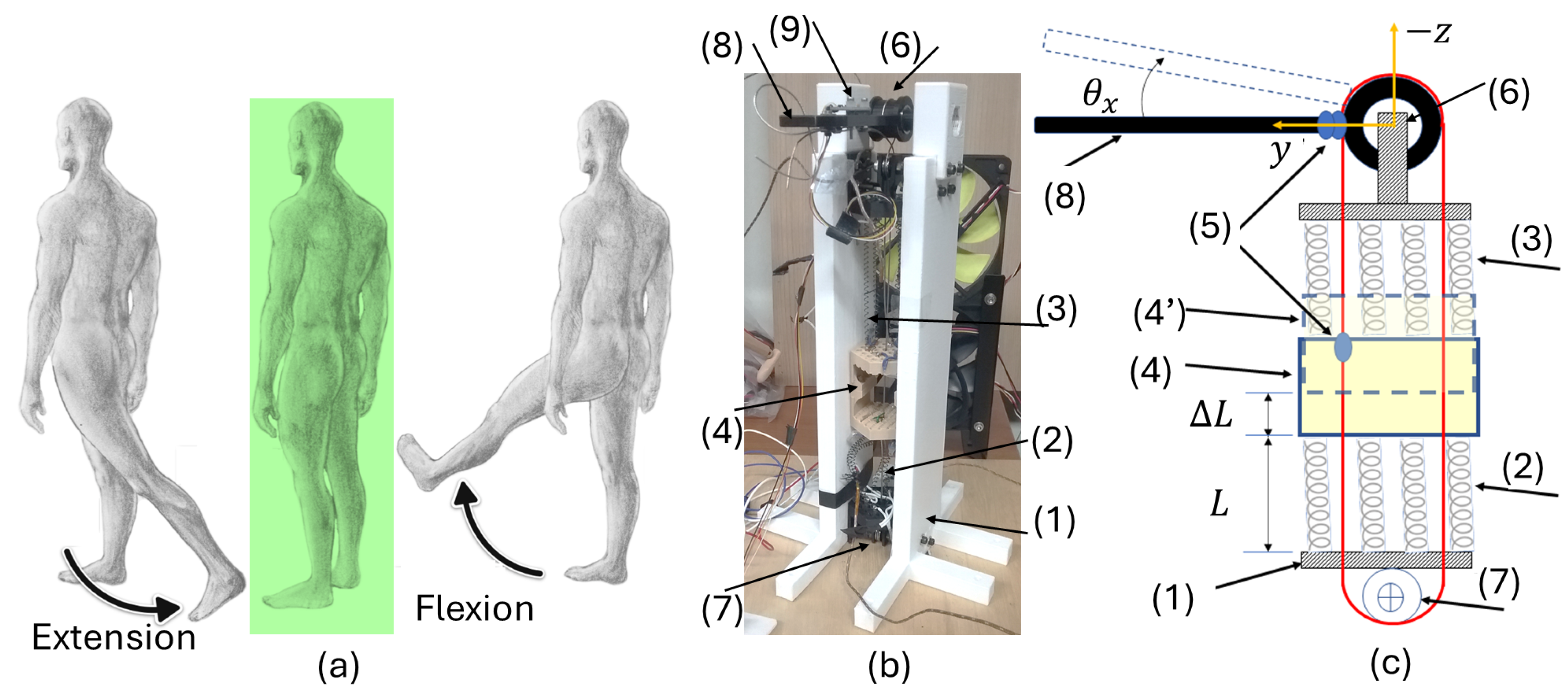

2. Architecture of the System

3. Mathematical Modeling

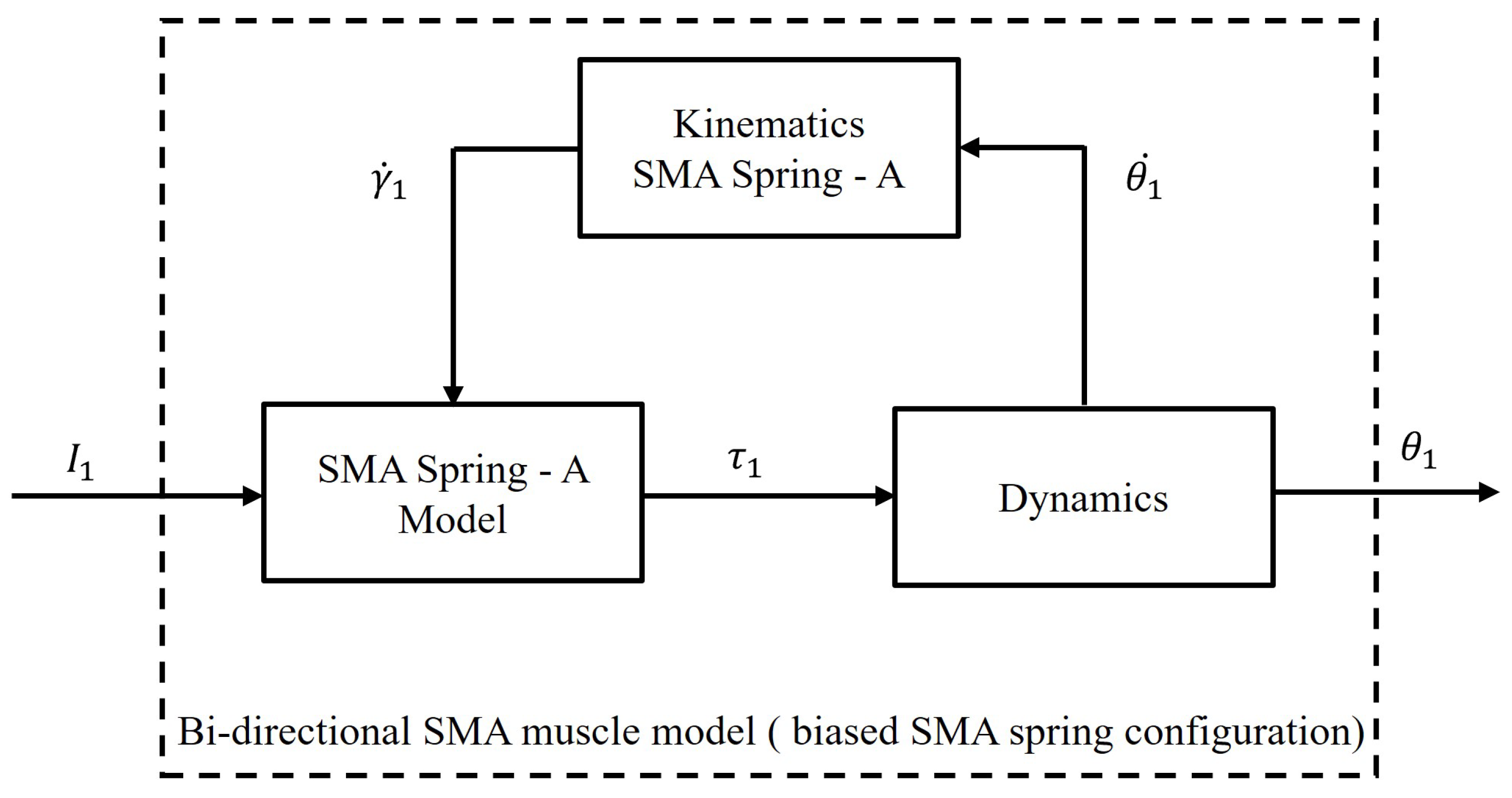

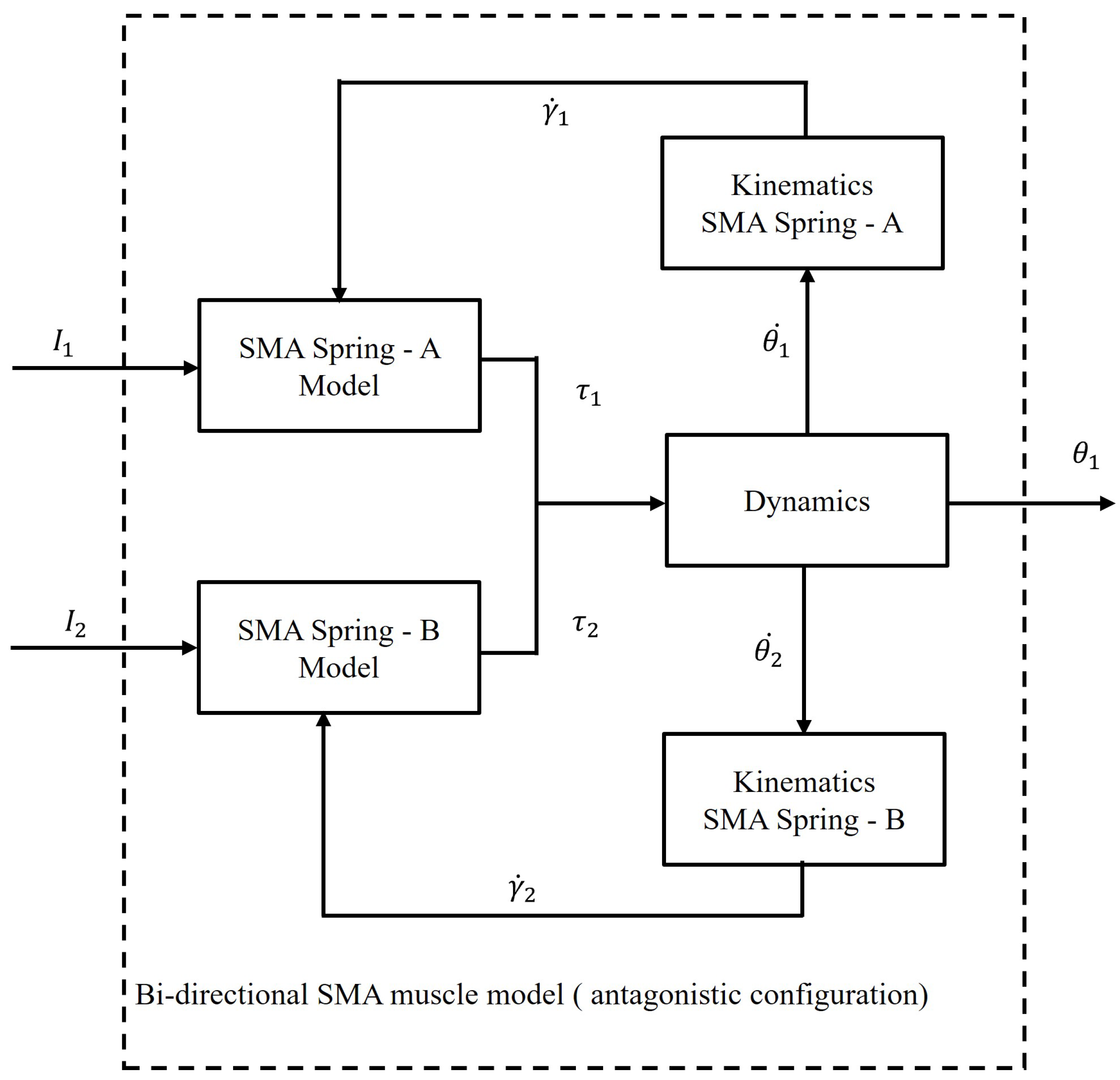

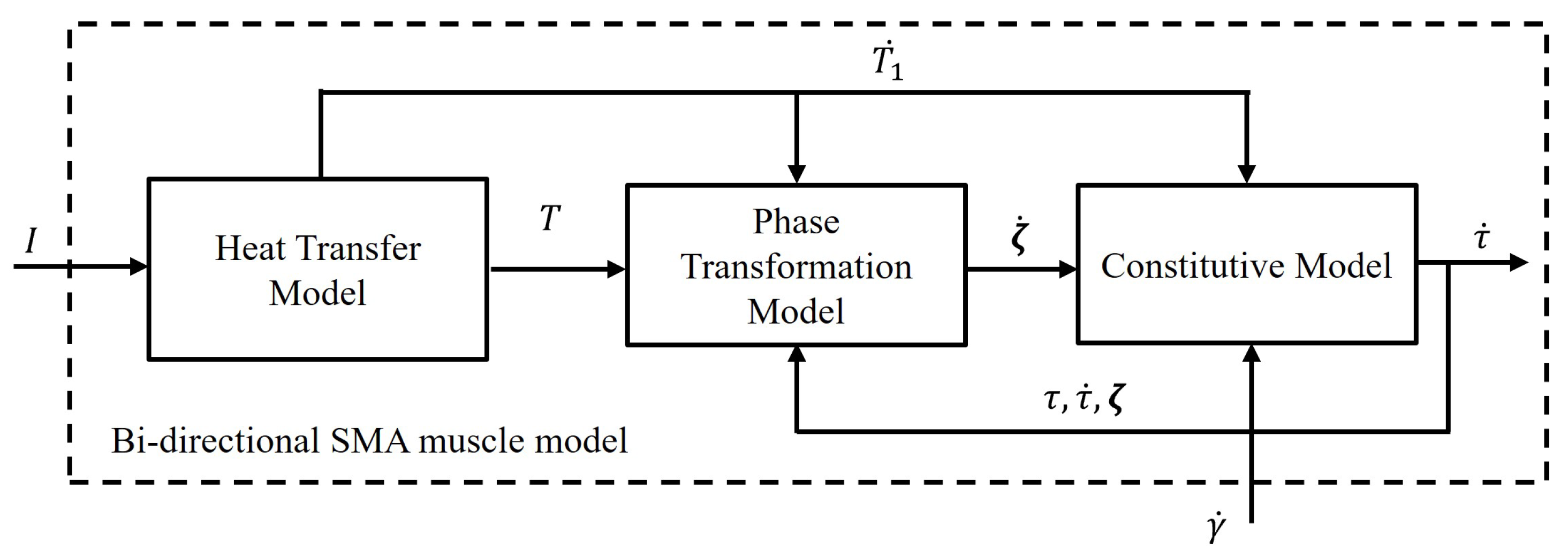

3.1. Model of the Bi-Directional SMA Muscle

3.2. SMA Spring Mathematical Model

3.3. Heat Transfer Model

3.4. Kinematic Model

4. Control Algorithm

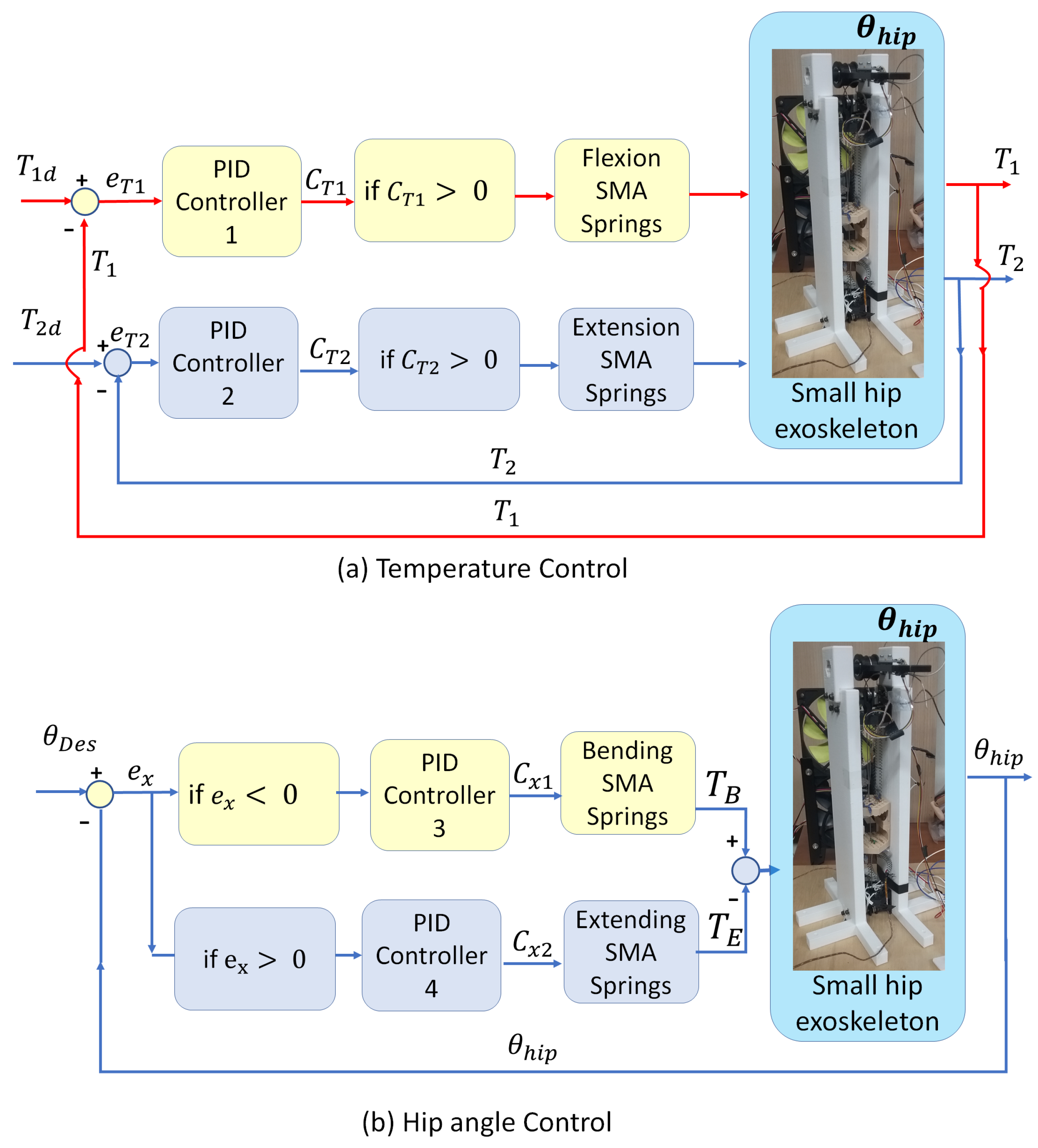

4.1. SMA Temperature Control

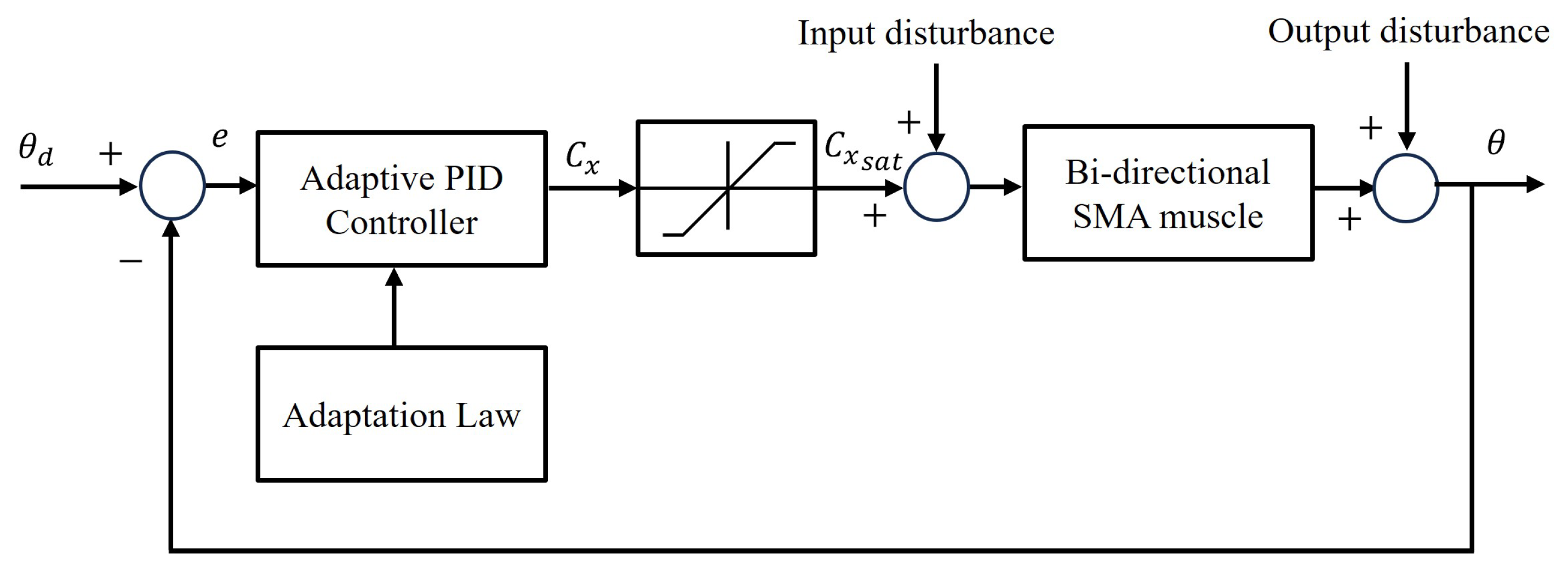

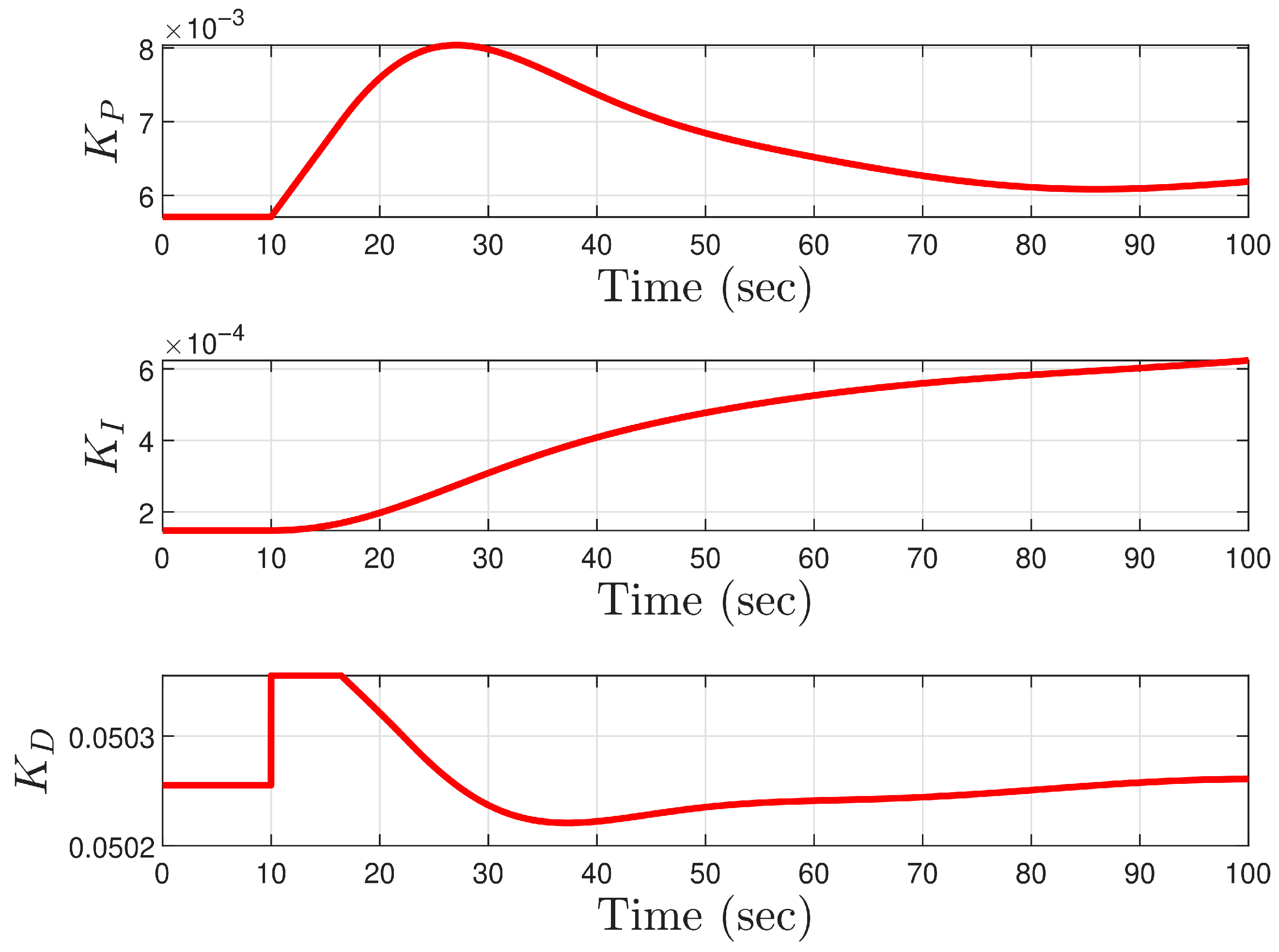

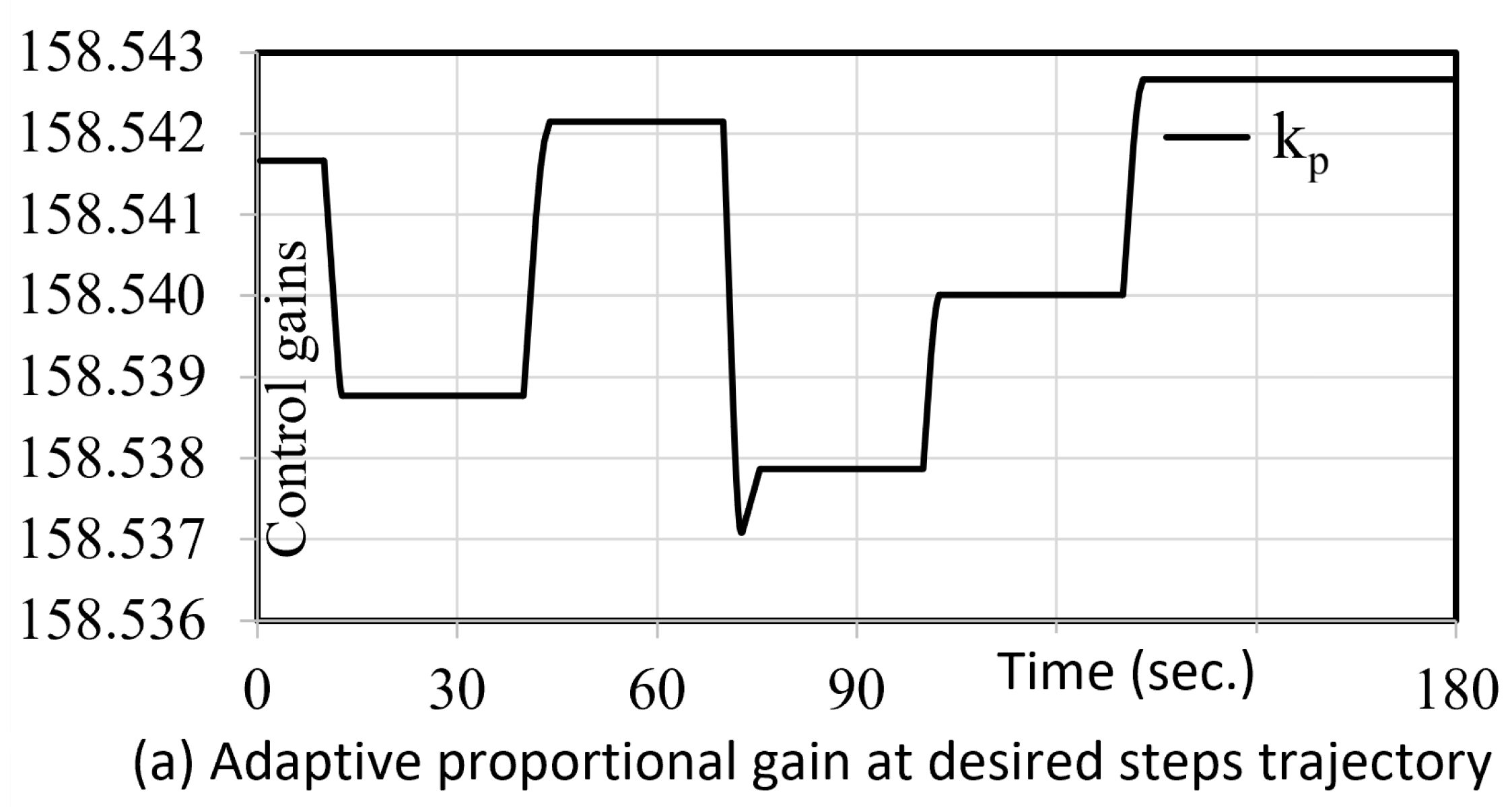

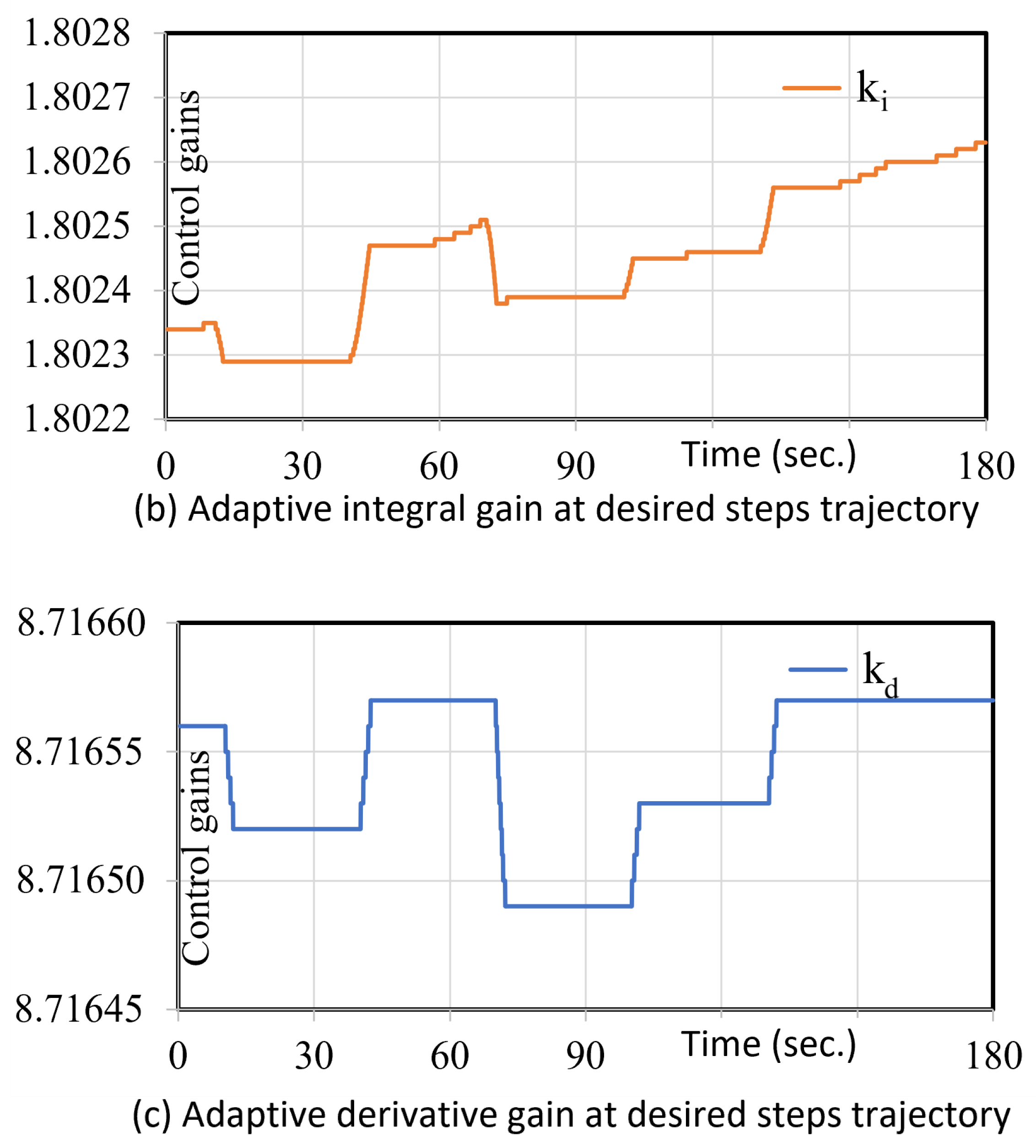

4.2. Adaptive PID Controller

5. Estimation and System Identification

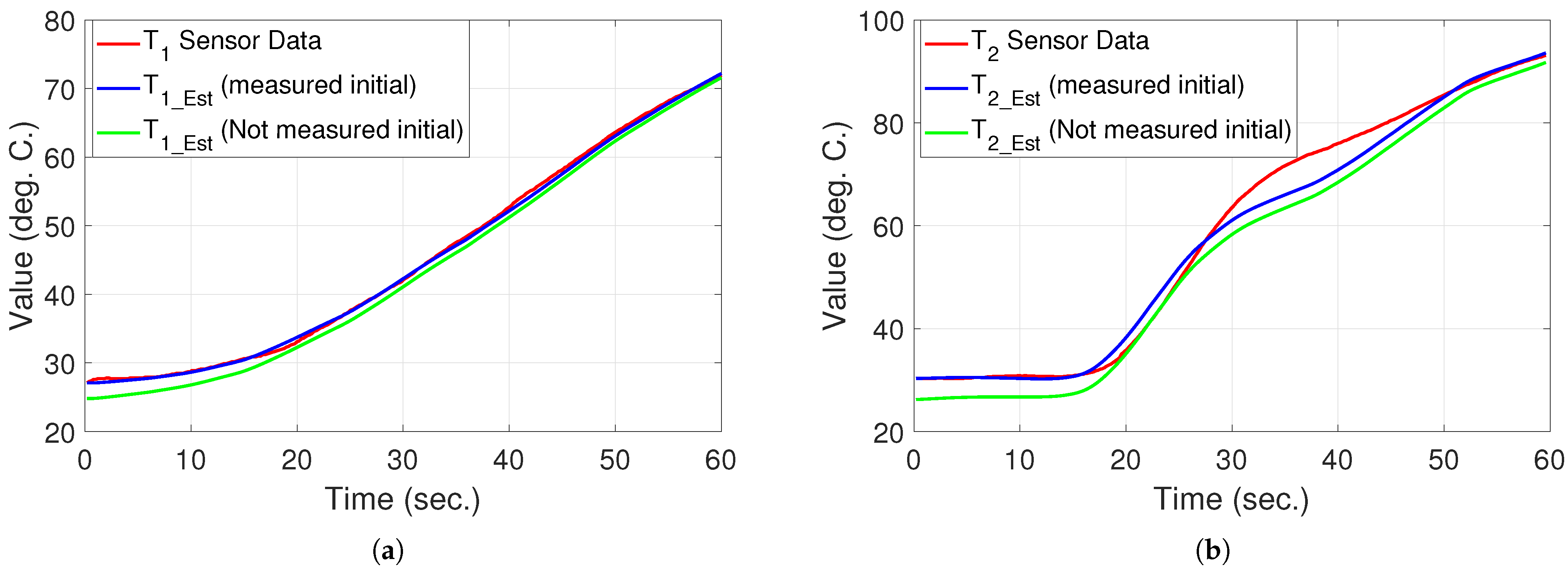

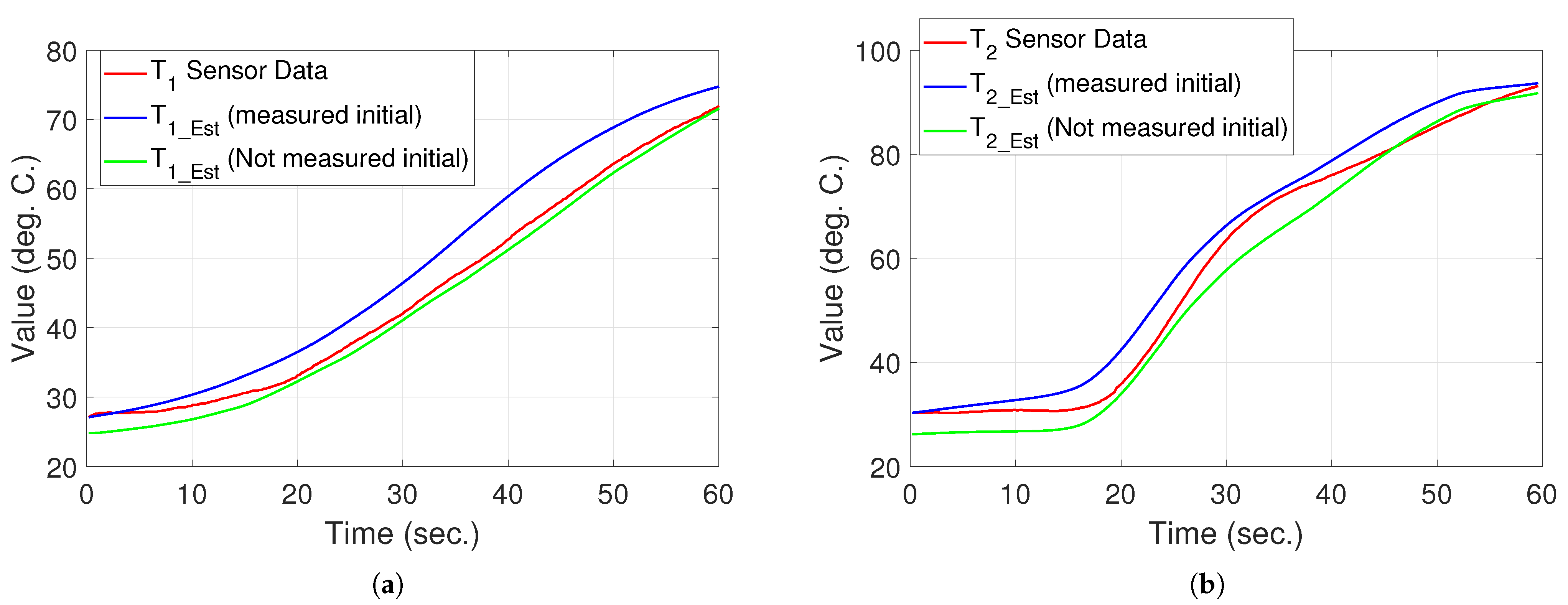

5.1. Temperature Estimation

- The first case: the initial temperature is measured and trusted.

- The second case: the initial temperature is not measured, and hence, we assumed the initial temperature equals .

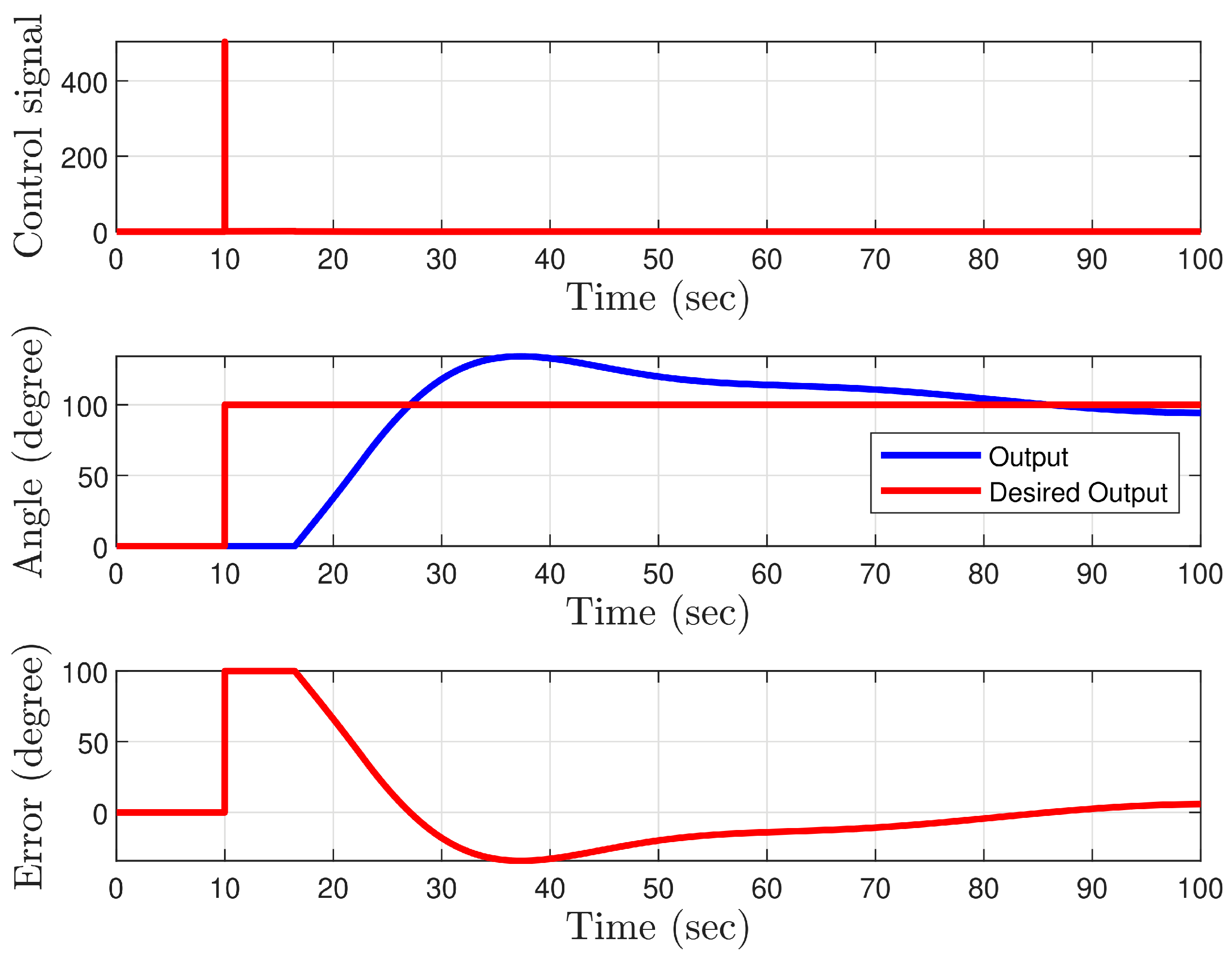

5.2. System Identification with Controller Tuning

- 1.

- Initially, a step input was applied, causing the desired hip angle to shift from to .

- 2.

- Subsequently, with the flexion operation data (SMA springs group B active), we tested several transfer function structures using the System Identification Toolbox and compared the estimation fitness and prediction errors, as summarized in Table 1.

- 3.

- After several trials, the system was best represented by a transfer function with two poles and a time delay, achieving a fitness of , which can be represented as follows:

- 4.

- Using this transfer function, we further fine-tuned the PID controller to enhance the system’s response time and transient behavior. The chosen PID gains for the controller were as follows: Proportional Gain () = 0.00518, Integral Gain () = 0.00001, Derivative Gain () = 0.05697. The simulation results with these PID gains yielded a rise time of s, a settling time of s, and an overshoot of . These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the tuned PID controller in achieving improved performance for the hip exoskeleton system.

- 5.

- Then, with the extension operation data (SMA springs group A is active), we tested several transfer functions structure using the System Identification Toolbox and compared the estimation fitness and prediction errors, as summarized in Table 2.

- 6.

- We chose the transfer function that had an underdamped pair and delay, with fitness:

- 7.

- Accordingly, we tuned the PID controller to enhance both the system’s response time and the transient characteristics of the system. We used the PID gains: , , , and the simulation results: rise time = s, settling time 290 s, overshoot .

- 8.

- Then, we executed the control experiments, as described in the next section.

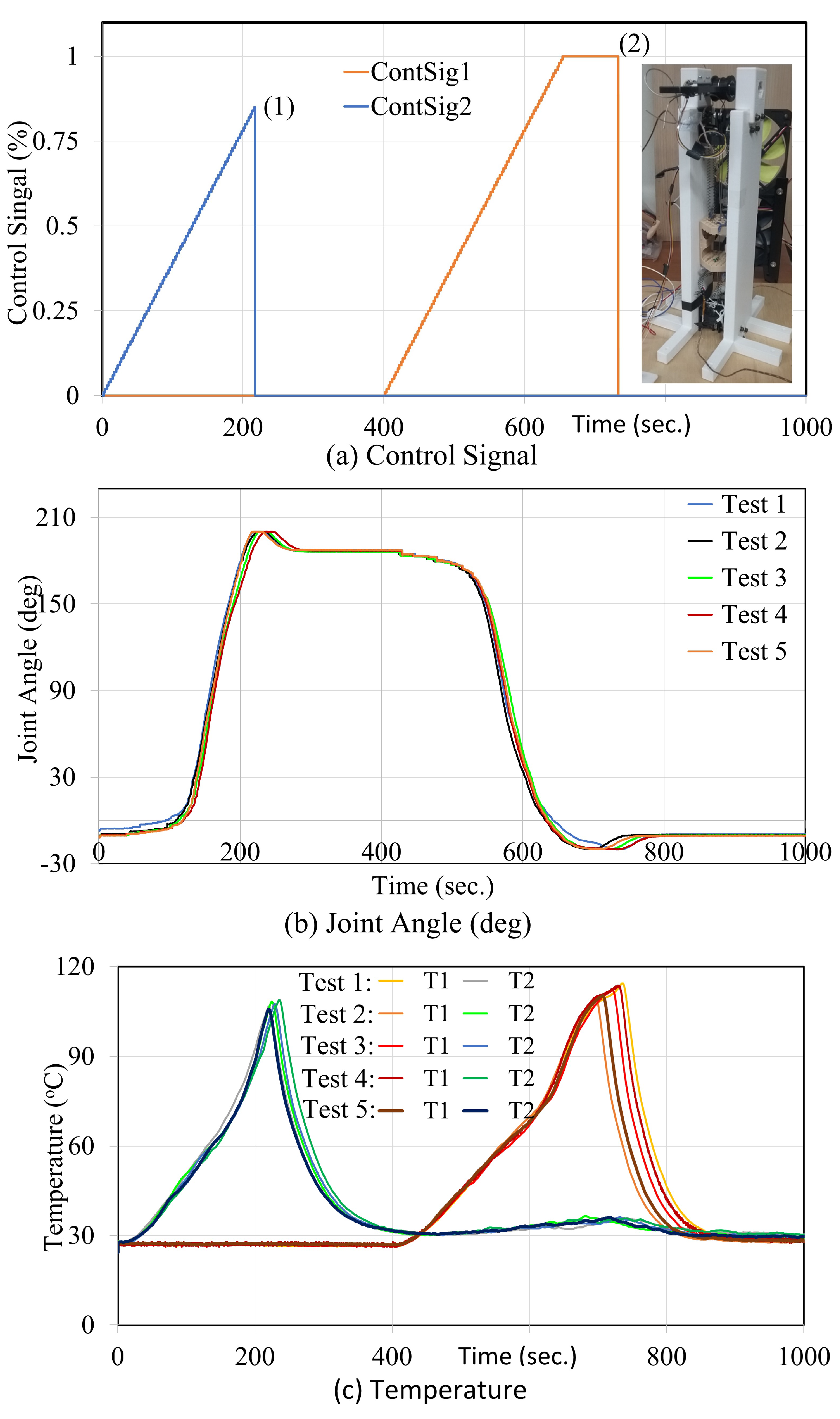

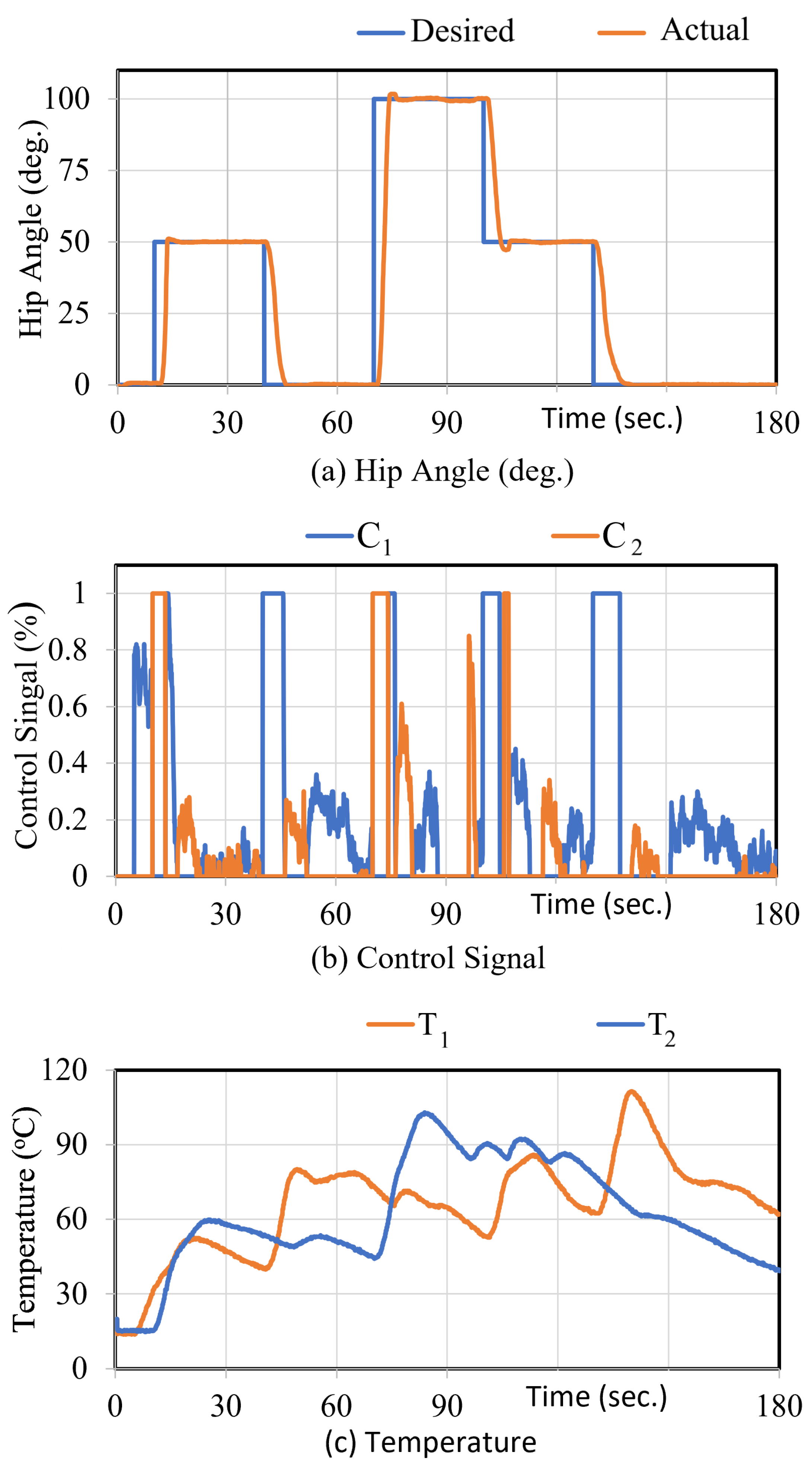

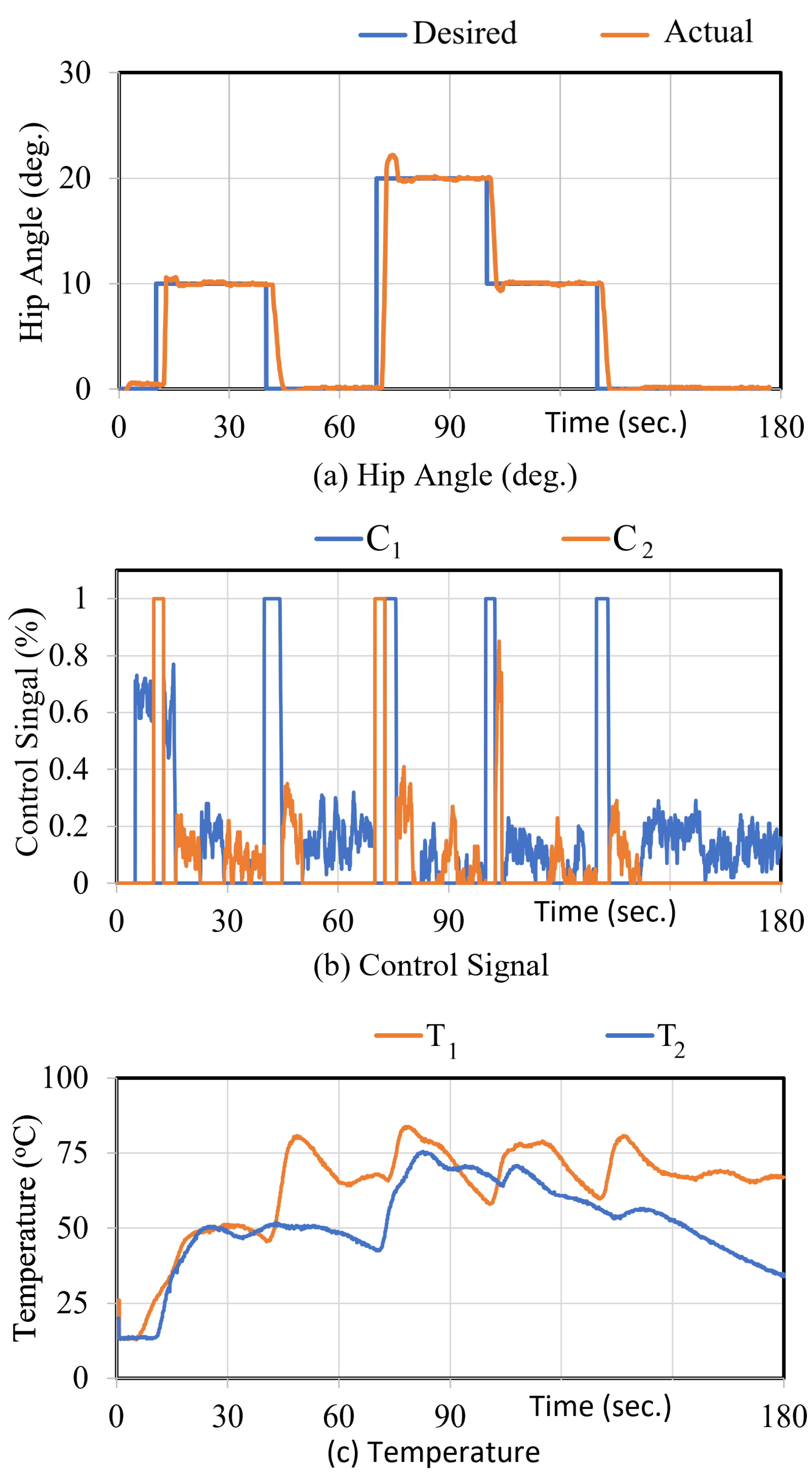

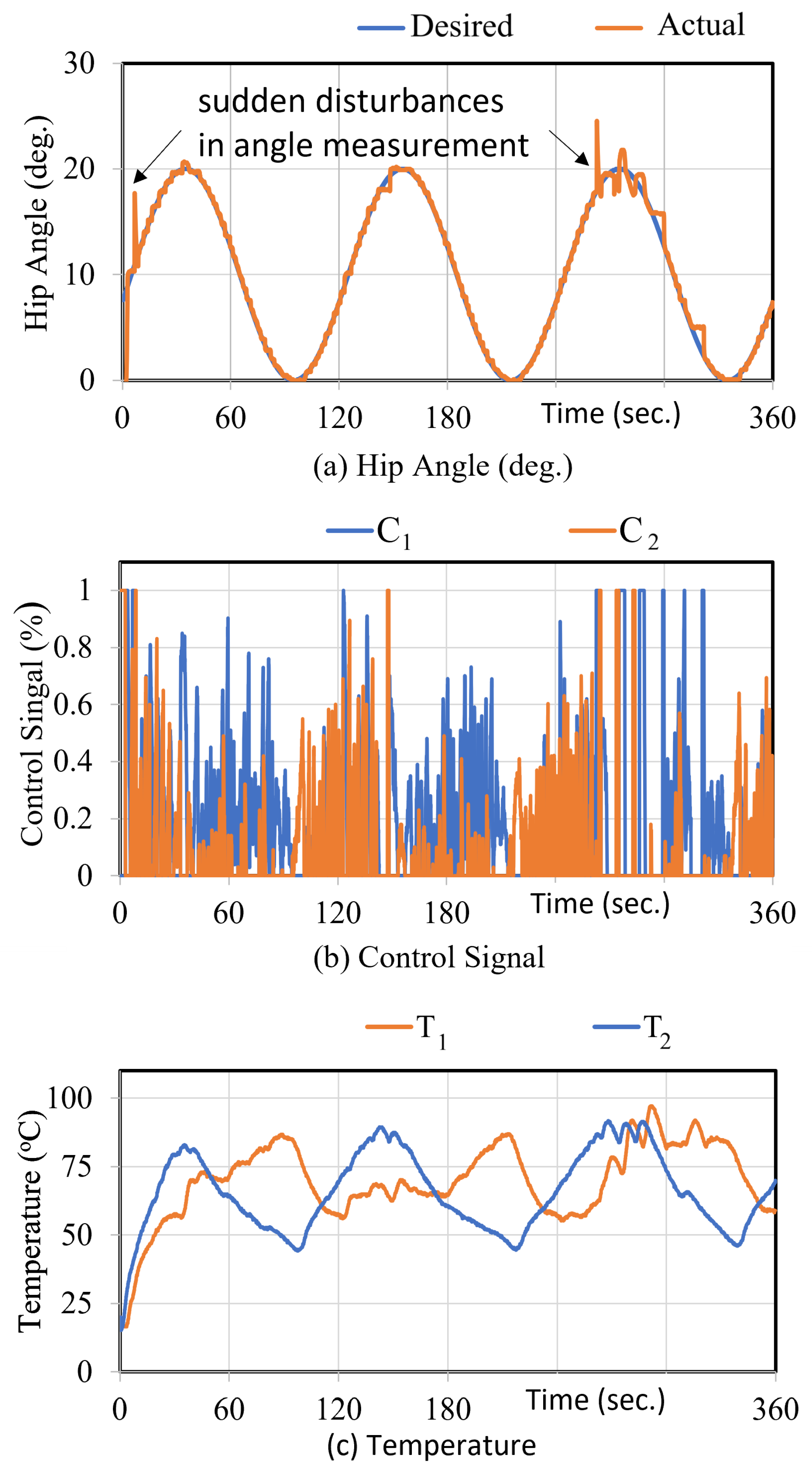

6. Experimental Results

6.1. Artificial Muscle Characterization

6.2. Control Experimental Results

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Disability and Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Meda-Gutiérrez, J.R.; Zúñiga-Avilés, L.A.; Vilchis-González, A.H.; Ávila-Vilchis, J.C. Knee Exoskeletons Design Approaches to Boost Strength Capability: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Yuan, C.; Liang, X.; Dong, T.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Zou, J.; Yang, H.; Bowen, C. Soft actuators and robotic devices for rehabilitation and assistance. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Hong, N.; Ryu, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S. Soft robot review. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 2017, 15, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miriyev, A.; Stack, K.; Lipson, H. Soft material for soft actuators. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Meng, Q.; Yu, W.; Xu, R.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Yu, H. Design of a soft bionic elbow exoskeleton based on shape memory alloy spring actuators. Mech. Sci. 2023, 14, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copaci, D.; Arias, J.; Moreno, L.; Blanco, D. Shape Memory Alloy (SMA)-Based Exoskeletons for Upper Limb Rehabilitation. In Rehabilitation of the Human Bone-Muscle System; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Sun, S.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Yun, G.; Chang, R.; Tang, S.Y.; Nakano, M.; Li, Z.; Du, H.; et al. Equipping new sma artificial muscles with controllable mrf exoskeletons for robotic manipulators and grippers. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2022, 27, 4585–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cong, M.; Liu, D.; Du, Y.; Ma, H. A lightweight variable stiffness knee exoskeleton driven by shape memory alloy. Ind. Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2022, 49, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cong, M.; Liu, D.; Du, Y.; Ma, H. Design of an active and passive control system for a knee exoskeleton with variable stiffness based on a shape memory alloy. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 101, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W. Design and Prototype Testing of a Smart SMA Actuator for UAV Foldable Tail Wings. Actuators 2024, 13, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauksher, R.; Patterson, Z.; Majidi, C. Characterization and analysis of a flexural shape memory alloy actuator. Actuators 2021, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jia, Z.; Niu, X.; Dong, E. Design and Position Control of a Bionic Joint Actuated by Shape Memory Alloy Wires. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copaci, D.; Blanco, D.; Moreno, L.E. Flexible shape-memory alloy-based actuator: Mechanical design optimization according to application. Actuators 2019, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, D.J.S.; Sohn, J.W.; Dhanalakshmi, K.; Choi, S.B. Control Aspects of Shape Memory Alloys in Robotics Applications: A Review over the Last Decade. Sensors 2022, 22, 4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.M.; Ryu, J.; Cho, M.; Cho, K.J. Engineering design framework for a shape memory alloy coil spring actuator using a static two-state model. Smart Mater. Struct. 2012, 21, 055009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, J.M.; Leary, M.; Subic, A.; Gibson, M.A. A review of shape memory alloy research, applications and opportunities. Mater. Des. 2014, 56, 1078–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Salazar, A.; Sugahara, Y.; Matsuura, D.; Takeda, Y. Scalable output linear actuators, a novel design concept using shape memory alloy wires driven by fluid temperature. Machines 2021, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DynalloyInc. FLEXINOL(R) Actuator Spring Technical and Design Data. 2024. Available online: https://dynalloy.com/tech-spring-data/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Park, H.B.; Kim, D.R.; Kim, H.J.; Wang, W.; Han, M.W.; Ahn, S.H. Design and analysis of artificial muscle robotic elbow joint using shape memory alloy actuator. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2020, 21, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, F.; Raparelli, T.; Beomonte Zobel, P. Resistance Feedback of a Ni-Ti Alloy Actuator at Room Temperature in Still Air. Micromachines 2024, 15, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Alsamhi, S.H.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Shape memory alloy-based wearables: A review, and conceptual frameworks on HCI and HRI in industry 4.0. Sensors 2022, 22, 6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengel, Y.A.; Ghajar, A.J. Heat and Mass Transfer: Fundamentals and Applications; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez Vega, R.; Cubas, G.; Sandoval-Chileño, M.A.; Castañeda Briones, L.Á.; Lozada-Castillo, N.B.; Luviano-Juárez, A. Position Measurements Using Magnetic Sensors for a Shape Memory Alloy Linear Actuator. Sensors 2022, 22, 7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Bezzaoucha, S.; Quintanar-Guzman, S.; Olivares-Mendez, M.A.; Voos, H. Adaptive control of robotic arm with hysteretic joint. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Control, Mechatronics and Automation, Barcelona, Spain, 7–11 December 2016; pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, H. Output-Feedback Adaptive Neural Control of a Compliant Differential SMA Actuator. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2017, 25, 2202–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, N.T.; Ahn, K.K. Output Feedback Direct Adaptive Controller for a SMA Actuator With a Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2012, 20, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, N.T.; Ahn, K.K. Adaptive proportional–integral–derivative tuning sliding mode control for a shape memory alloy actuator. Smart Mater. Struct. 2011, 20, 055010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, E.T.; Elahinia, M.H. Developing an Adaptive Controller for a Shape Memory Alloy Walking Assistive Device. J. Vib. Control 2010, 16, 1897–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Abbasimoshaei, A.; Kitajima Borges, J.P.; Kern, T.A. Numerical and Experimental Study of a Wearable Exo-Glove for Telerehabilitation Application using Shape Memory Alloy actuators. Actuators 2024, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla Navarro, P.; Copaci, D.; Arias, J.; Blanco Rojas, D. Design of an SMA-based actuator for replicating normal gait patterns in pediatric patients with cerebral palsy. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, C.; Copaci, D.; Arias, J.; Moreno, L.; Blanco, D. Hoist-based shape memory alloy actuator with multiple wires for high-displacement applications. Actuators 2023, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.F.; Baek, H.; Jang, T.; Kim, Y. Finger-Like Mechanism Using Bending Shape Memory Alloys. In Proceedings of the ASME 2020 29th Conference on Information Storage and Processing Systems, Virtual, 24–25 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.F.; Khan, A.M.; Baek, H.; Shin, B.; Kim, Y. Modeling and control of a finger-like mechanism using bending shape memory alloys. Microsyst. Technol. 2021, 27, 2481–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.F.; Kim, Y. Design of a 2 DOF Shape Memory Alloy Actuator using SMA Springs. In Proceedings of the ASME 2021 30th Conference on Information Storage and Processing Systems, Virtual, 2–3 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.F.; Kim, Y.; Le, Q.H.; Shin, B. Modeling and control of two DOF shape memory alloy actuators with applications. Microsyst. Technol. 2022, 28, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Mansour, N.A.; Khan, A.M.; Bijalwan, V.; Ali, H.F.; Kim, Y. SMA-based caterpillar robot using antagonistic actuation. Microsyst. Technol. 2023, 29, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.F.; Kim, Y. Novel artificial muscle using shape memory alloy spring bundles in honeycomb architecture in Bi-directions. Microsyst. Technol. 2022, 28, 2315–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.F.; Kim, Y. Design Procedure and Control of a Small-Scale Knee Exoskeleton using Shape Memory Alloy Springs. Microsyst. Technol. 2023, 29, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.F.; Kim, Y. Novel design and fabrication of a linear actuator based on shape memory alloy wire winding in hexagonal architecture. Microsyst. Technol. 2023, 29, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.F.; Kim, Y.; Mohamed, S. Linear System Identification and Control of a Small-Scale Hip Exoskeleton Using Shape Memory Alloy Springs in Hexagonal Architecture. In Proceedings of the Information Storage and Processing Systems, Milpitas, CA, USA, 28–29 August 2023; Volume 87219, p. V001T07A004. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.F.; Mansour, N.A.; Kim, Y. Comparative study of extended and unscented Kalman filters for estimating motion states of an autonomous vehicle–trailer system. In Recent Advances in Mechanical Engineering: Select Proceedings of ICRAME 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Elahinia, M.H.; Ahmadian, M. An enhanced SMA phenomenological model: I. The shortcomings of the existing models. Smart Mater. Struct. 2005, 14, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K. A thermomechanical sketch of shape memory effect: One-dimensional tensile behavior. Res. Mech. 1986, 18, 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Tobushi, H.; Tanaka, K. Deformation of a shape memory alloy helical spring: Analysis based on stress-strain-temperature relation. JSME Int. J. Ser. 1 Solid Mech. Strength Mater. 1991, 34, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X. Advanced Sliding Mode Control for Mechanical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, G. Multivariable adaptive control: A survey. Automatica 2014, 50, 2737–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Transfer Function Form | Fitness | Error |

|---|---|---|

| One pole with delay | 81.4% | 26.35 |

| Two poles with delay | 95.15% | 1.08 |

| Underdamped pair with delay | 96.51% | 0.93 |

| Underdamped pair, real pole, delay | 93.73% | 3.04 |

| Transfer Function Form | Fitness | Error |

|---|---|---|

| One pole with delay | 47.13% | 392.56 |

| Two poles with delay | 52.42% | 319.52 |

| Underdamped pair with delay | 88.1% | 19.99 |

| Underdamped pair, real pole, delay | 55.73% | 282.086 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ali, H.F.M.; Kim, Y.; Ahmad, E.; Mohamed, S. Temperature Estimation of Thin Shape Memory Alloy Springs in a Small-Scale Hip Exoskeleton with System Identification and Adaptive Control. Actuators 2026, 15, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010026

Ali HFM, Kim Y, Ahmad E, Mohamed S. Temperature Estimation of Thin Shape Memory Alloy Springs in a Small-Scale Hip Exoskeleton with System Identification and Adaptive Control. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Hussein F. M., Youngshik Kim, Ejaz Ahmad, and Shuaiby Mohamed. 2026. "Temperature Estimation of Thin Shape Memory Alloy Springs in a Small-Scale Hip Exoskeleton with System Identification and Adaptive Control" Actuators 15, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010026

APA StyleAli, H. F. M., Kim, Y., Ahmad, E., & Mohamed, S. (2026). Temperature Estimation of Thin Shape Memory Alloy Springs in a Small-Scale Hip Exoskeleton with System Identification and Adaptive Control. Actuators, 15(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010026