An Adaptive Preload Device for High-Speed Motorized Spindles for Teaching and Scientific Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

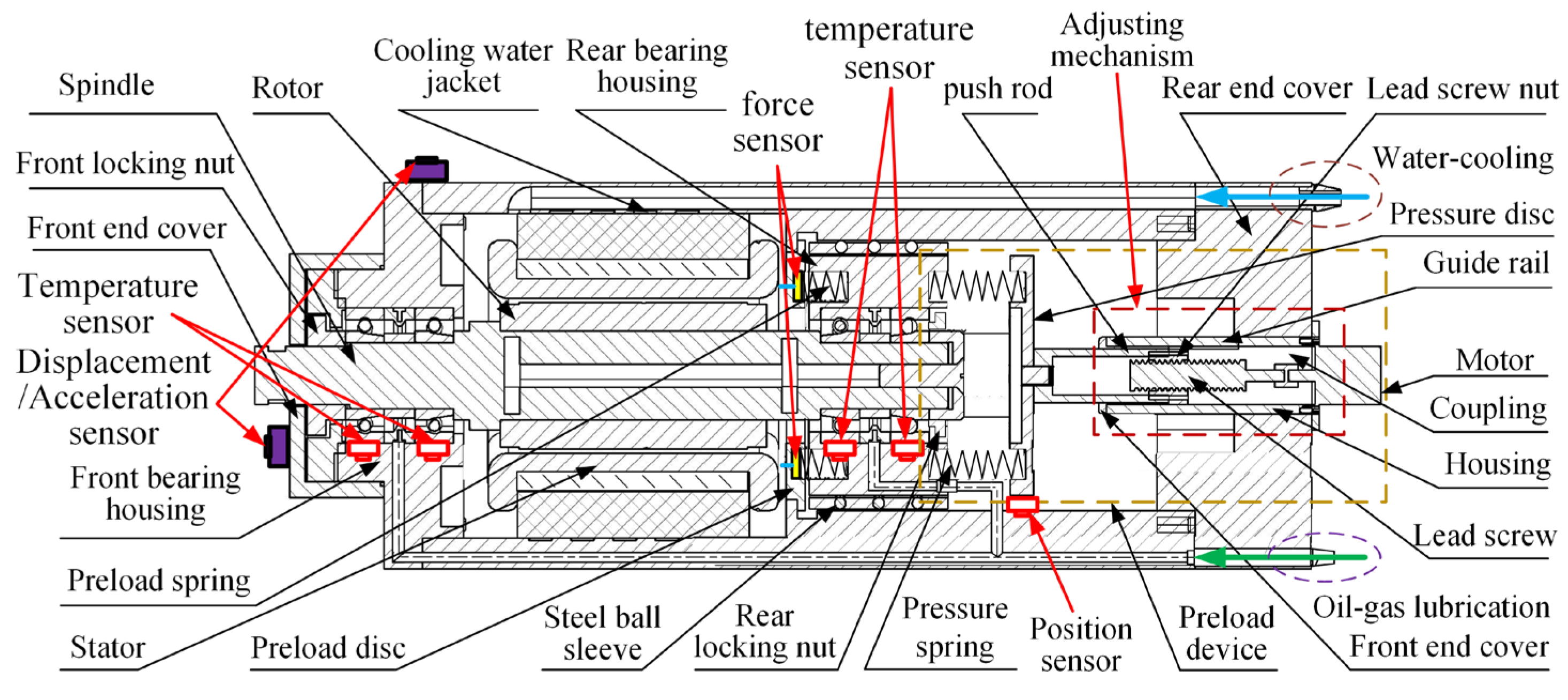

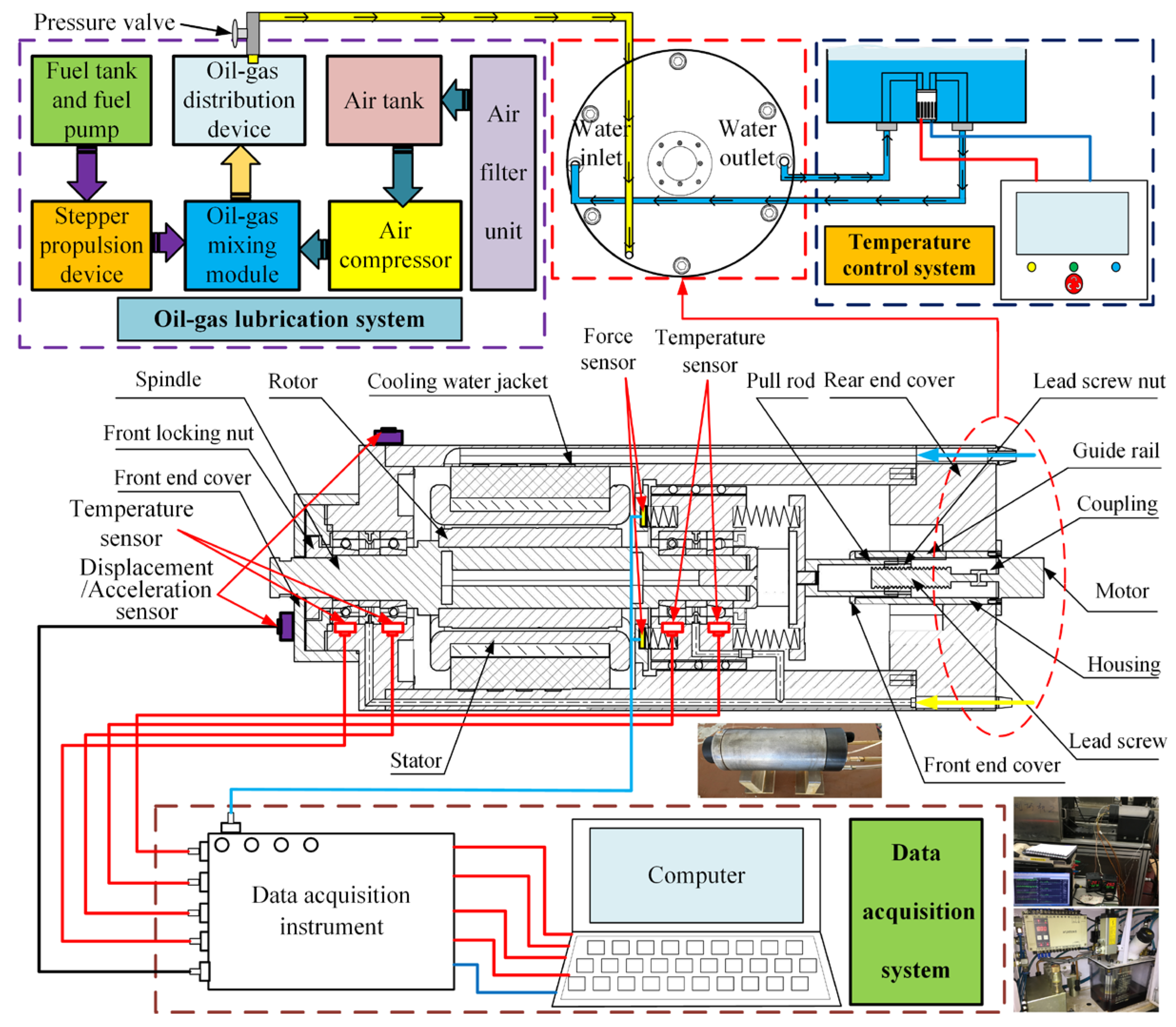

2. Design of Adaptive Preload Motorized Spindle

2.1. Motorized Spindle and Preload Device

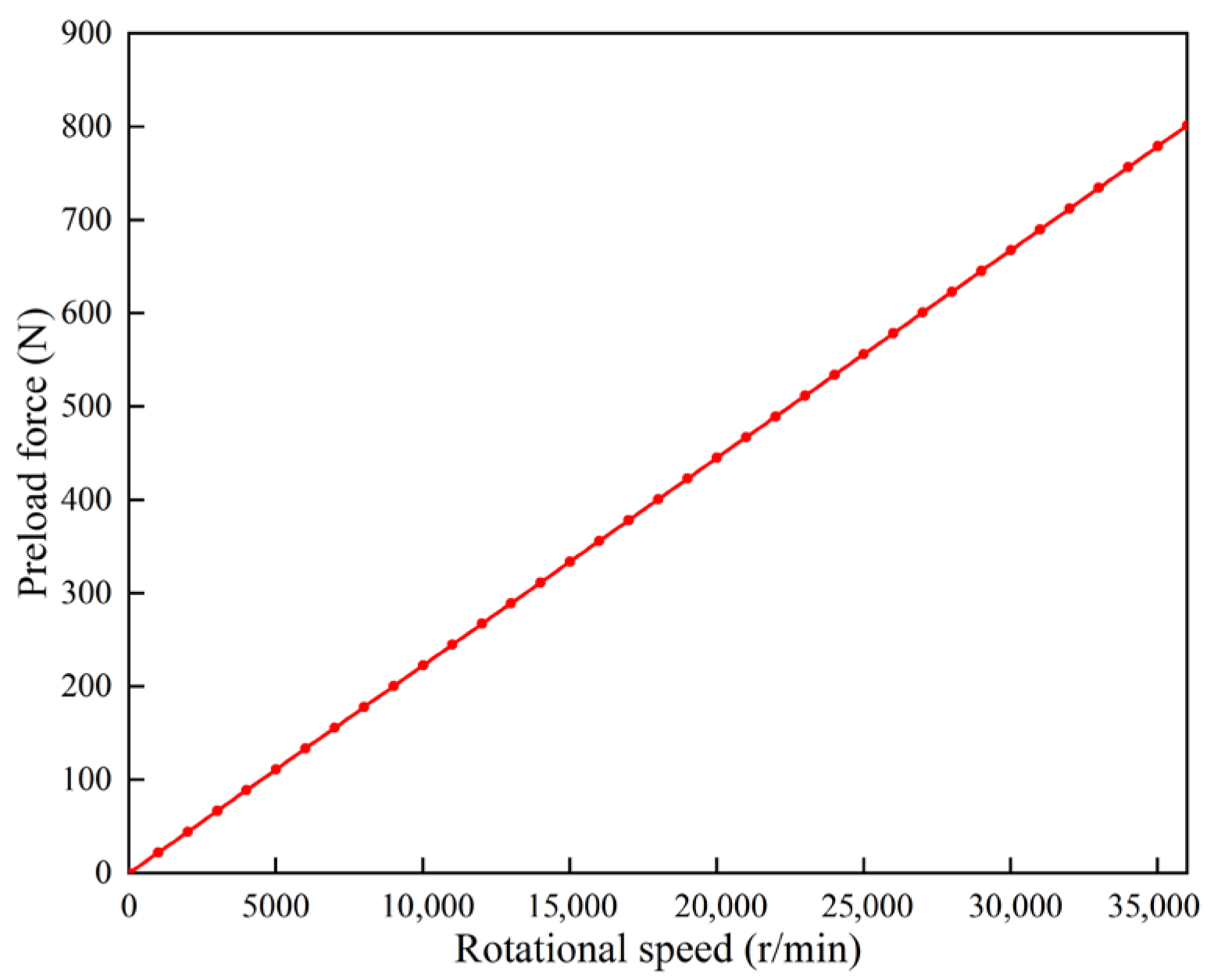

2.2. Preload Theory for Motorized Spindle

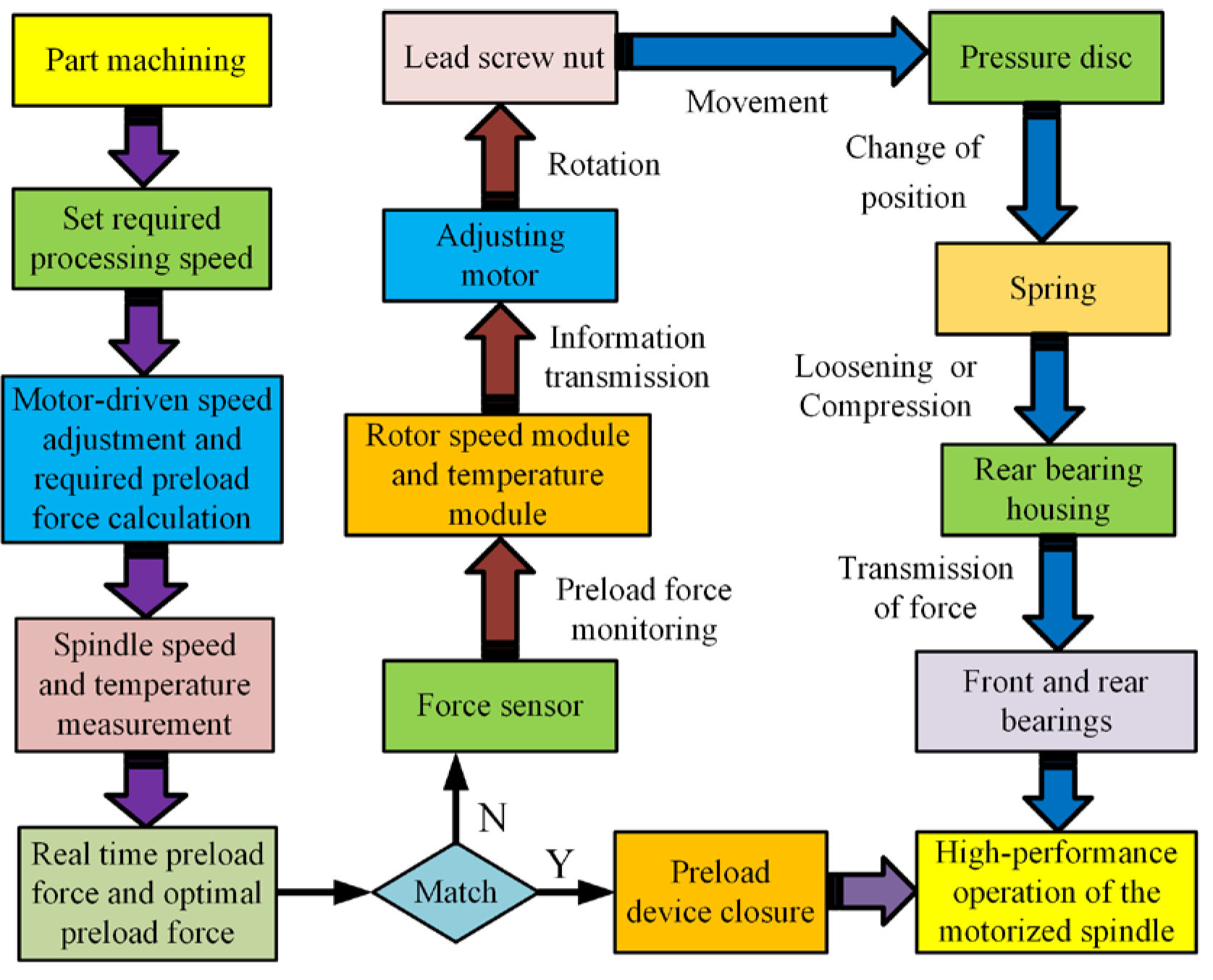

2.3. Principle of Adaptive Adjustment for Preload Force

3. Verification and Results Analysis

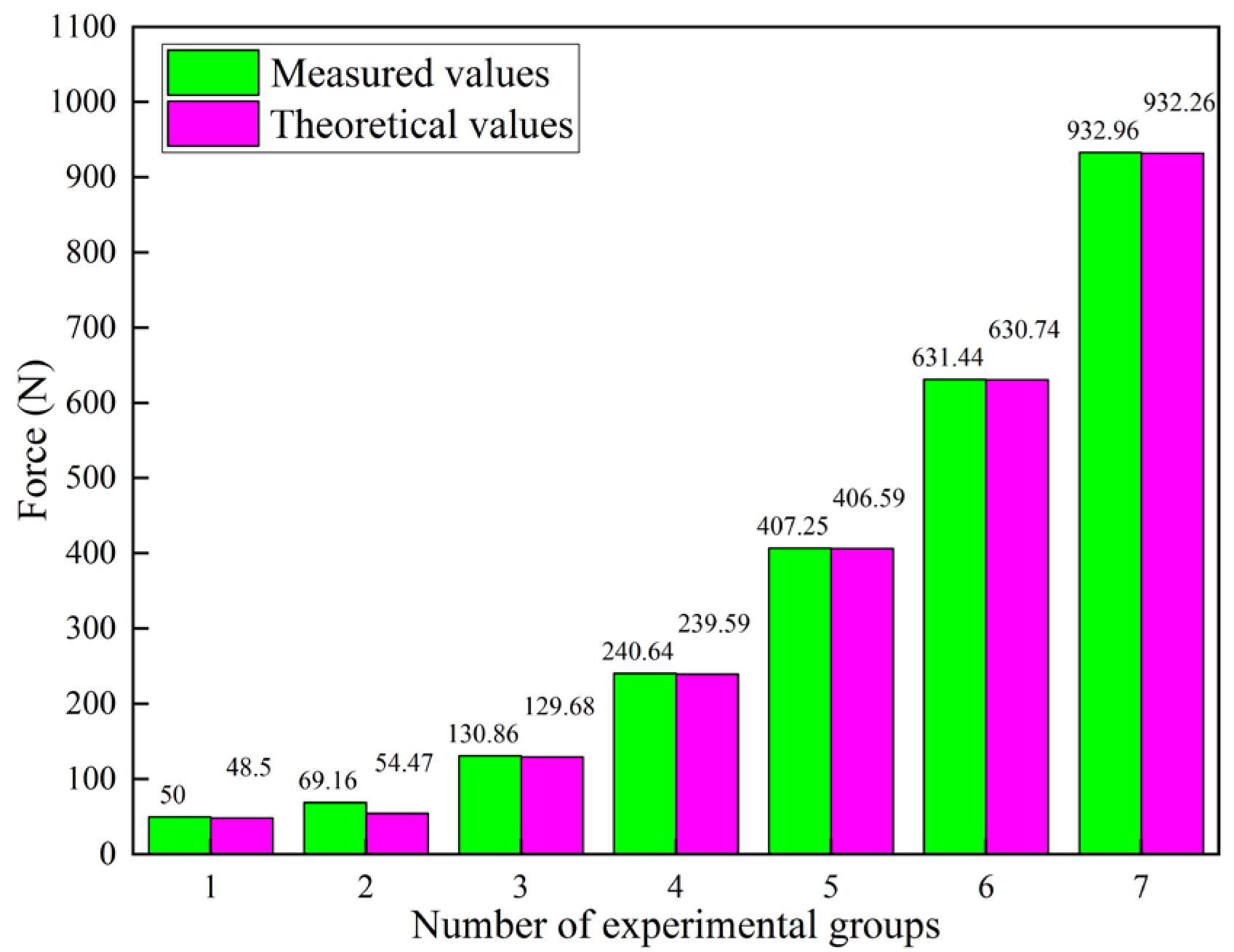

3.1. Calibration of Preload Device

3.2. Experimental Objective

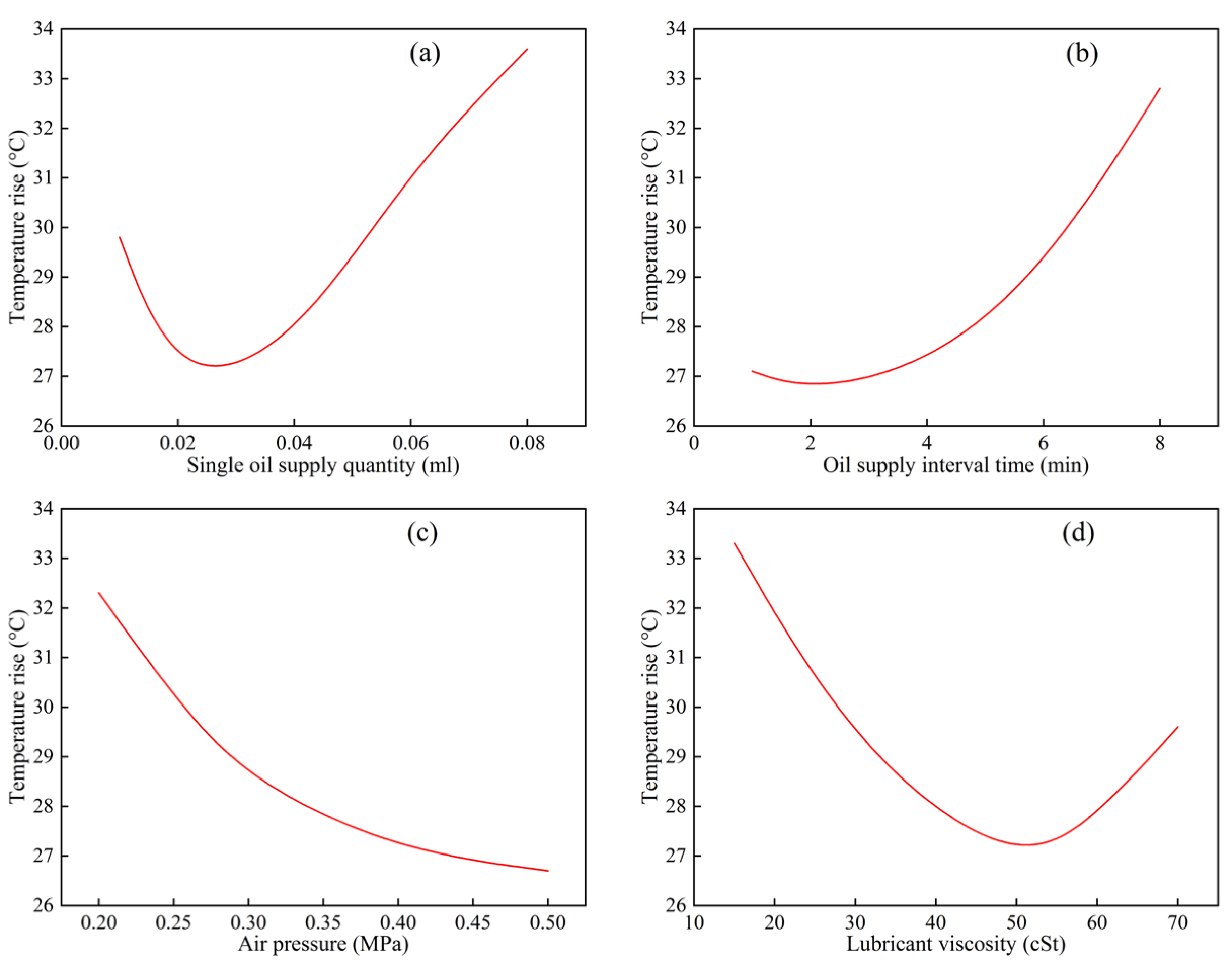

3.3. Experimental Procedure

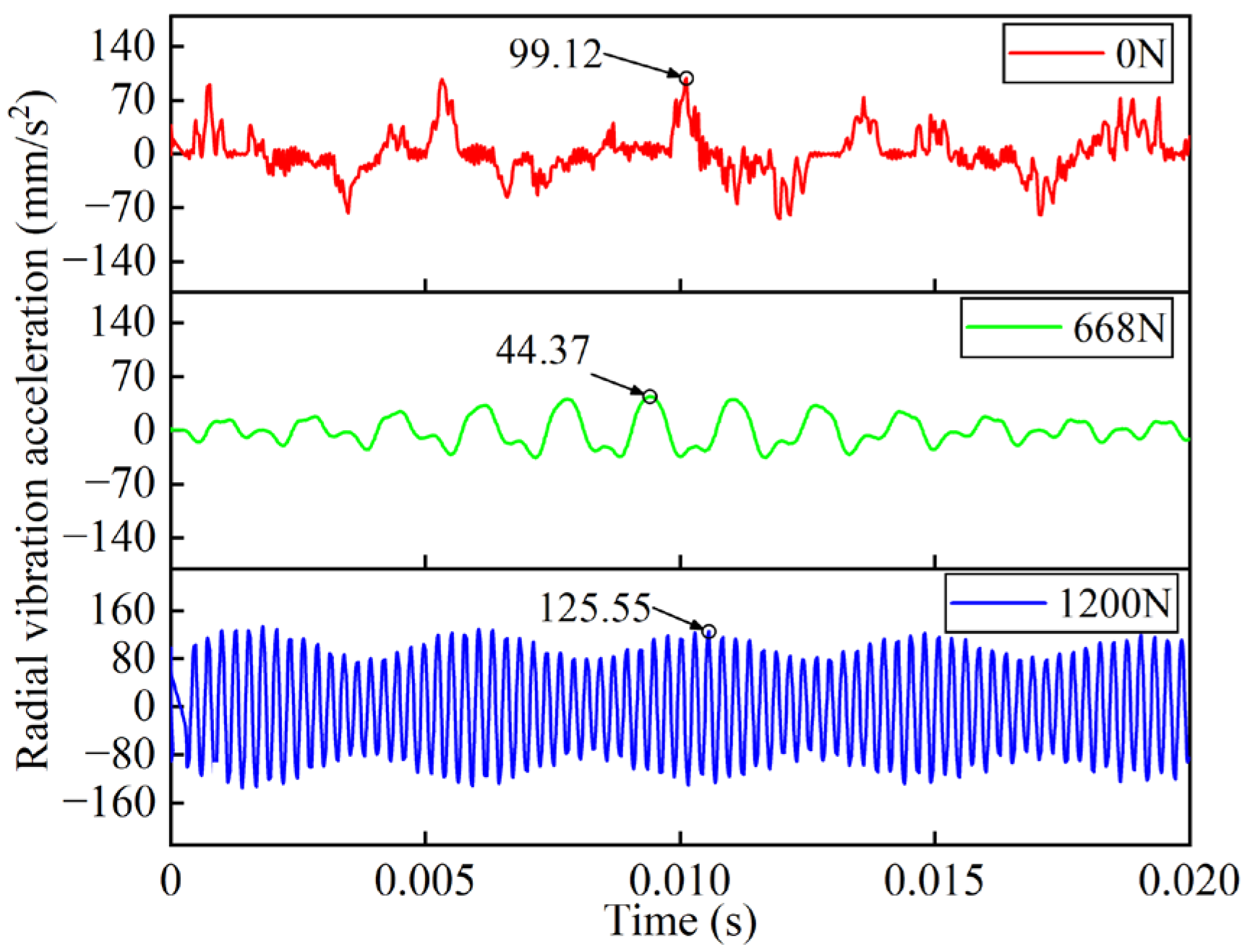

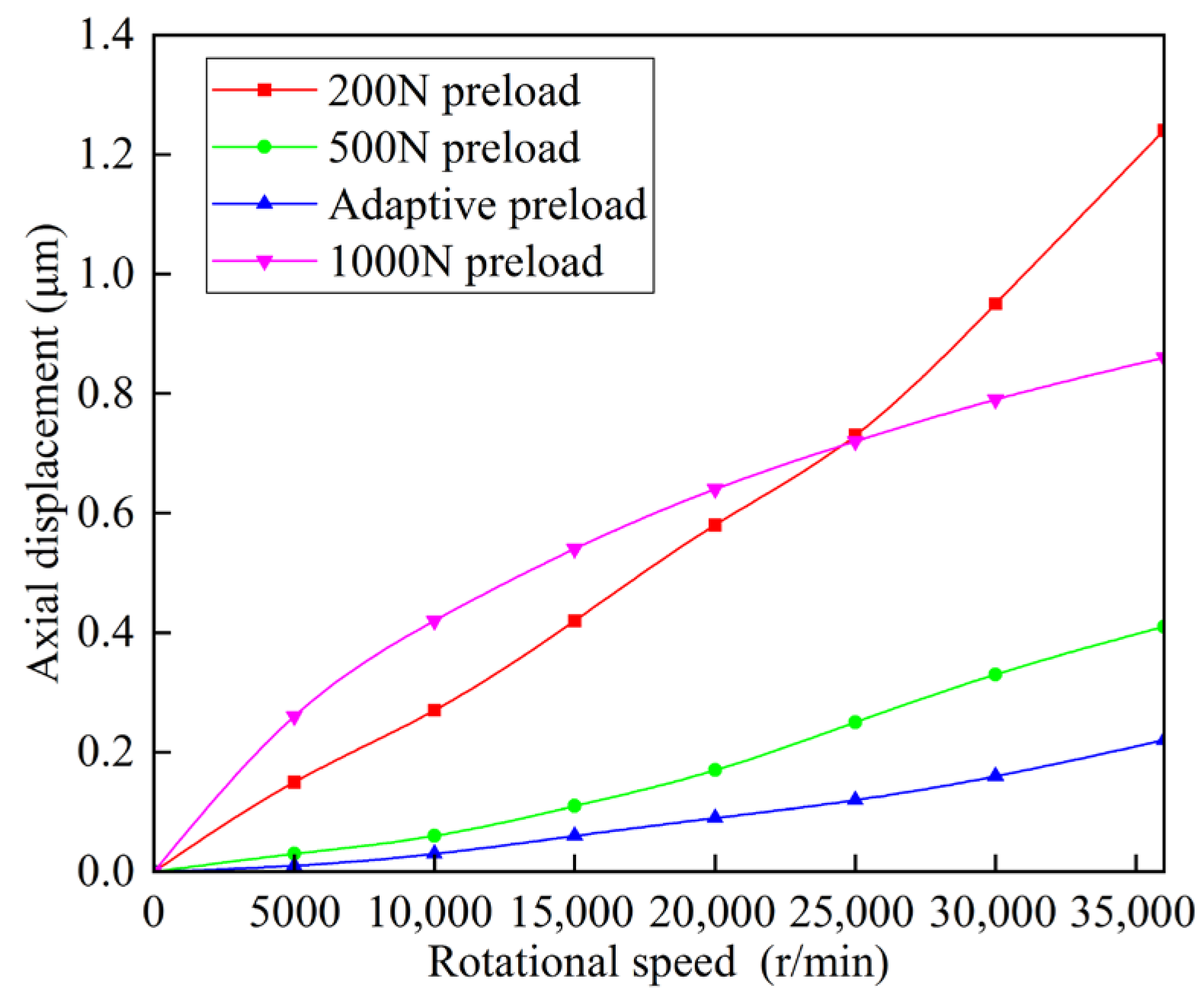

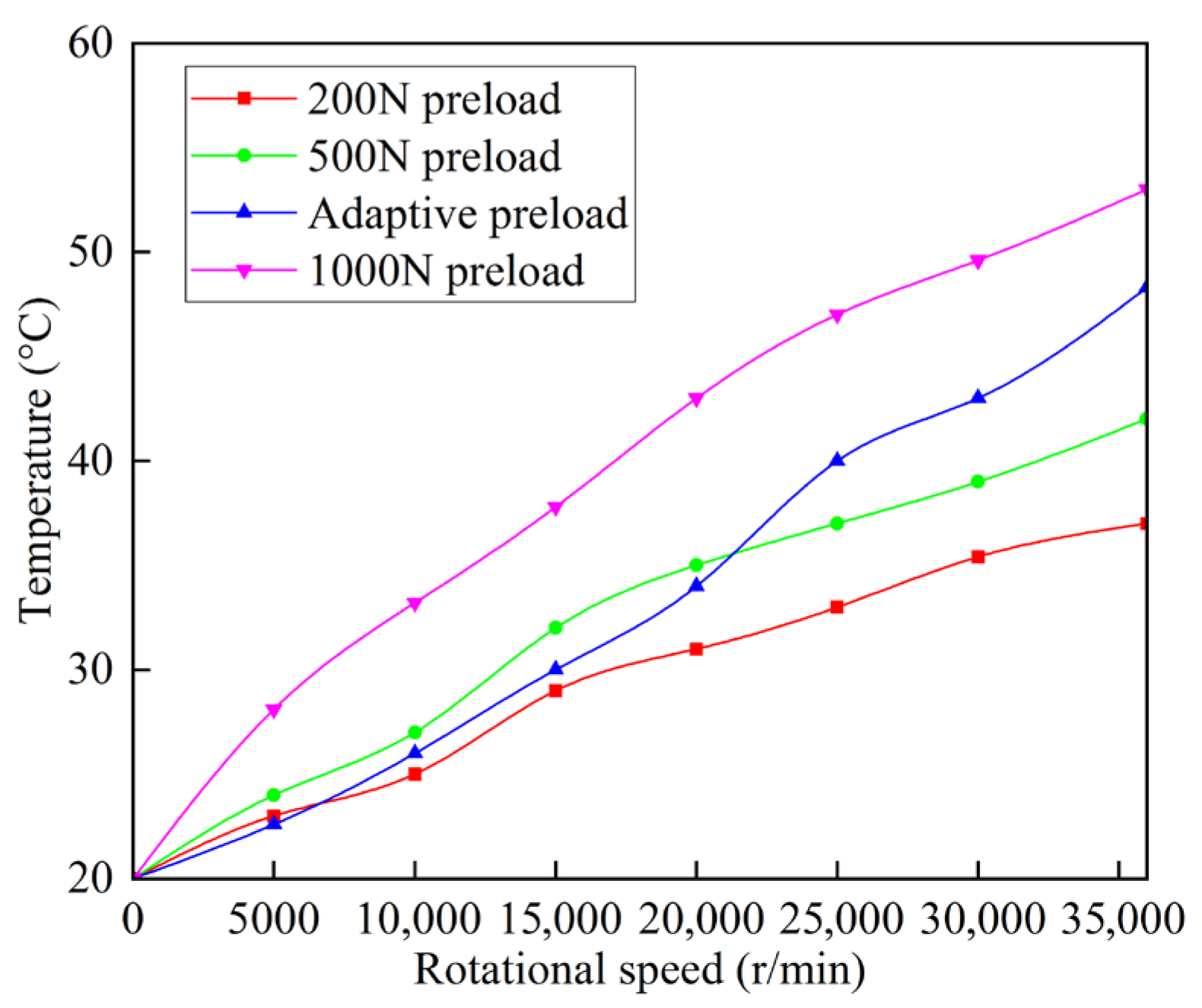

3.4. Results Analysis

4. Application in Teaching and Scientific Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dai, Y.; Tao, X.S.; Li, Z.L.; Zhan, S.Q.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.H. A review of key technologies for high-speed motorized spindles of CNC machine tools. Machines 2022, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.L.; Chen, X.A.; He, Y.; Chen, T.C.; Li, P.M. A dynamic loading system for high-speed motorized spindle with magnetorheological fluid. J. Intel. Mat. Syst. Str. 2018, 29, 2754–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Lee, C.M. A variable preload device using liquid pressure for machine tools spindles. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Man. 2012, 13, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yu, B.L.; Tao, X.S.; Wang, X.; He, S.; Wang, G. Thermal displacement prediction of variable preload motorized spindles based on speed reduction experiments and IABC-BP optimization models. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 53, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.P.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Z.X.; Zhao, F.; Kong, X.X.; Wen, B.C. The influence of rolling bearing parameters on the nonlinear dynamic response and cutting stability of high-speed spindle systems. Mech. Syst. Sig. Process. 2020, 136, 106448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Li, C.Y.; Song, W.J.; Yao, Z.H.; Miao, H.H.; Xu, M.T.; Gong, X.X.; Lu, H.; Liu, Z.D. Thermal-mechanical dynamic interaction in high-speed motorized spindle considering nonlinear vibration. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 240, 107959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Wan, S.K.; Zhang, J.H.; Yan, K.; Hong, J. A comprehensive study of the effect of thermal deformation on the dynamic characteristics of the high-speed spindle unit with various preload forces. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 203, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.P.; Gao, F.; Li, Y.; Wu, W.W.; Zhang, D.Y. Research on optimization of spindle bearing preload based on the efficiency coefficient method. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2020, 73, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razban, M.; Movahhedy, M.R. A speed-dependent variable preload system for high speed spindles. Precis. Eng. 2015, 40, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, C.M. Development of an automatic variable preload device using uniformly distributed eccentric mass for a high-speed spindle. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Man. 2017, 18, 1419–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.F.; Zhang, D.W.; Gao, W.G.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Tian, Y.L. Study on variable pressure/position preload spindle-bearing system by using piezoelectric actuators under close-loop control. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Manu. 2018, 125, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, F. Motion of a ball in angular-contact ball bearing. ASLE Trans. 1965, 8, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaviana, L.; Tong, V.C.; Hong, S.W. Skidding analysis of angular contact ball bearing subjected to radial load and angular misalignment. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2019, 33, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.Y.; Ma, J.; Liu, A.X.; Niu, S.Q.; Hu, B.B. The analysis of the bearing fit effect on spindle rotor system vibration. Acad. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 4, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, P. Spindle bearing preload control using NI MyRIO. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.X.; Wu, Y.H.; Sun, J.; Xia, Z.X.; Ren, K.X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.H.; Yao, J.M. Thermal dynamic exploration of full-ceramic ball bearings under the self-lubrication condition. Lubricants 2022, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.T.; Su, B.; Zhang, S.L.; Yang, H.S.; Cui, Y.C. Dynamics-based thermal analysis of high-speed angular contact ball bearings with under-race lubrication. Machines 2023, 11, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.P.; Wu, Y.H.; Li, S.H.; Zhang, L.X.; Zhang, K. The effect of factors on the radiation noise of high-speed full ceramic angular contact ball bearings. Shock Vib. 2018, 2018, 1645878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Xu, T.; Dai, Y.; Chen, T.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.J. Thermal characteristics analysis of machine tool spindle with adjustable bearing preload. J Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Single Oil Supply Quantity (mL) | Oil Supply Interval Time (min) | Air Pressure (MPa) | Lubricant Viscosity (cSt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.20 | 15 |

| 2 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.25 | 30 |

| 3 | 0.04 | 4 | 0.30 | 50 |

| 4 | 0.06 | 6 | 0.40 | 60 |

| 5 | 0.08 | 8 | 0.50 | 70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhu, J.; Sun, T. An Adaptive Preload Device for High-Speed Motorized Spindles for Teaching and Scientific Research. Actuators 2025, 14, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120591

Yan H, Zhang Z, Wang G, Zhu J, Sun T. An Adaptive Preload Device for High-Speed Motorized Spindles for Teaching and Scientific Research. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120591

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Haipeng, Zongchu Zhang, Guisen Wang, Jinda Zhu, and Tingting Sun. 2025. "An Adaptive Preload Device for High-Speed Motorized Spindles for Teaching and Scientific Research" Actuators 14, no. 12: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120591

APA StyleYan, H., Zhang, Z., Wang, G., Zhu, J., & Sun, T. (2025). An Adaptive Preload Device for High-Speed Motorized Spindles for Teaching and Scientific Research. Actuators, 14(12), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120591