1. Introduction

Resonant converters are commonly utilized today in applications requiring precise and efficient energy transfer, such as in the cellphone industry [

1], inductive cooking for domestic use [

2], wireless power chargers for electric vehicles [

3,

4], magnetic levitation systems for a variety of transportation solutions [

5], wireless charging of biomedical implants [

6] and induction heating in the metal industry [

7]. These converters are generally operated at high frequencies, which consequently causes the inductive reactance to restrict the power delivered to the load. For non-varying or limited-varying load, a resonant capacitor is then typically added for a constant, pre-calculated resonant frequency of the converter, supporting quasi-resonant operation. Modern resonant converters should dynamically track the resonant frequency of varying loads; i.e., resonance is sustained regardless of the load variations. Nonetheless, sustaining resonance under rapid load variations in highly nonlinear systems is challenging, especially in pulsed-power scenarios, where the desired response time of the system to the control signal is shorter than the settling time of the open-loop system. This challenge is evident in pulsed-power hydrogen fusion systems, in which plasma generation leads to large, rapid changes in both resistive and inductive load components [

8,

9]. Moreover, the capacitance of the resonant elements can shift as a result of temperature fluctuations, mechanical stresses from high current, or degradation [

10].

As an example, assume a sinusoidal source with constant magnitude and frequency

applied to a general series RLC network (assuming fixed parameter values for brevity) at

t = 0. The current flowing through the network would then be given by

. In steady state, the linear time-invariant nature of the system imposes

with constant

,

and

. However, within the transient response, the instantaneous current amplitude and frequency fluctuate, leading to

and

. On the other hand, instantaneous current frequency may be expressed as

. Hence, the current flowing through the network may be expressed as

with

; thus, the varying frequency can be considered as a constant frequency with a time-varying phase, as shown in

Figure 1 [

11]. In practical pulsed-power operation, the inverter is not driven continuously but rather in a burst-mode manner. Here, the power stage is gated on only for a short time interval (a pulse) and then switched off (all the transistors are de-energized). In the example considered here, only the first 1 ms within the pulse is of interest, while the system would have reached steady state only around 2.75 ms if kept operating. Hence, steady-state phasor-domain analysis proves inadequate for analyzing the dynamics over the power-burst timeframe, and therefore, a time-domain-based analysis method that does not rely on the assumption of steady-state operation is needed.

Nonlinear systems can be characterized as systems with an unproportional output response to their input signal and often exhibit complex input-to-output dynamics, making their analysis and control design a challenging task. In systems with moderate nonlinearity, linearization [

12] is commonly used to simplify the described dynamics analysis. The use of linearization allows the construction of a system transfer function and, consequently, a further use of linear control theory tools [

13]. For systems that are highly nonlinear, the common, straightforward linearization techniques fail to adequately capture the system dynamics due to fast and substantial variations in the operating point of the system during operation; thus, the analysis of a linearized system model around a certain operating point will often lead to an invalid representation of the system and its input-to-output dynamics. One way to address this challenge is by adopting an approach in which the nonlinear relationship between the system input and output is explicitly identified and utilized in the controller design. In this case, the system’s nonlinearity can be specifically compensated for within the control scheme, resulting in a pseudo-linear system from the controller’s perspective. This simplification enables a linear control design and forms the basis for the suggested nonlinear control strategy. A recent study introduced an envelope modeling technique [

14], deriving a plant that accurately represents the system dynamics by capturing the amplitude and phase dynamics of the system. Although effective, traditional envelope modeling inherently increases the system plant model’s order, complicating the subsequent controller design task. Traditionally, in such cases, an order reduction procedure is applied. Commonly, reduced-order models [

15] rely on linearization techniques to achieve simplification; nonetheless, such an approach is only suitable for steady-state operating systems with small operating point variations, and thus struggles to correctly capture the behavior of highly operating point-varying systems. Another method to achieve a low-order envelope model based on the energetic coupling between the system inductance and capacitance was proposed in [

16]; however, it is only valid in a very close vicinity of resonance. The previously proposed reduced-order envelope model [

11] presents a way to alleviate high-order complexity, offering a more practical, lower-order plant, with a wide validity range, more suitable for controller design.

In this paper, previously derived full-order and reduced-order envelope models of the described system are introduced. Under the assumption of near-resonance operation, the reduced-order envelope model is further simplified and utilized to obtain the nonlinear relationship between the inverter switching frequency and its current phase. This relationship forms the core of a novel “nonlinearity compensation unit”, a mathematical part of the controller, possessing the relations between the system switching frequency and phase. From the controller’s perspective, integrating the above compensation unit into the controller yields a linear integrator-like input-to-output behavior of the control loop, thus simplifying the controller design process substantially. The resulting control approach provides a robust, effective, and easy-to-implement solution for managing highly nonlinear fast-varying systems, allowing the use of linear control tools that were previously invalid. The suggested control approach credibility is shown using simulations, and conclusions are given.

2. System Under Consideration and Basic Assumptions

The system under consideration comprises a resonant half-bridge converter feeding a series-connected resistor–inductor–capacitor (RLC) load with time-varying values, shown in

Figure 2. Large DC-side capacitors

Cin1 and

Cin2, pre-charged to a certain initial DC voltage, serve as the system’s energy source. Values of RLC network components are assumed to vary in time according to

where the first (zero-indexed) right-hand side term denotes a constant nominal value and the second right-hand term signifies a corresponding time-varying quantity.

In addition, relative rate of change in R(

t),

L(

t) and

C(

t) is significantly lower than angular converter switching frequency

ωs [rad/s] in practice. Consequently, RLC network component values are considered to remain constant during a single switching period

Ts [s]

= 1/

fs with

fs [Hz]

= ωs/2

. DC-side capacitances

Cin1 and

Cin2 (assumed to be equal, constant and known) are pre-charged to initial voltages of

vin1(0) =

vin2(0) =

vin(0) prior to burst creation at

t = 0. During operation, DC-side capacitances discharge to provide energy to resistance

R(

t). Nevertheless,

Cin1 and

Cin2 are typically high enough to assume that the average value of

vin(

t) remains unchanged during a single switching period

Ts. Converter switches operate in complementary fashion with duty cycle of 50% so that its output voltage

v(

t) may be approximated within a single switching period (neglecting parasitics for brevity) by a square-wave given by

and thus, described by the following Fourier series,

Lastly, it should be emphasized that while converter switching frequency varies in general, corresponding relative rate of change is significantly lower than ωs(t) itself.

3. System Modeling Review

The AC side of the circuit in

Figure 2 is governed by the following equation

where voltages across the inductance and the capacitance are related to the AC-side current as

and

respectively. As shown in [

13], operation in the vicinity of resonance yields nearly sinusoidal capacitor voltage and current (due to the bandpass-filtering nature of series RLC impedance), given by

and

respectively, where

VM(

t) and

IM(

t) stand for the corresponding magnitudes and

φv(

t) and

φi(

t) symbolize the corresponding phase angles [

17]. Further denoting

and

Equations (7) and (8) may be rewritten as

and

respectively. Combining (4)–(12), a set of four envelope dynamics state equations with corresponding general initial conditions may be established [

18,

19],

Output equations are derived from (9) and (10) as

Moreover, the switching-cycle-average power released by the DC link capacitors is dissipated by the RLC network resistance in the case of lossless conversion [

13], yielding the fifth state equation with corresponding general initial conditions, namely

with

denoting the switching-cycle-average value of

vin(

t). Consequently, the envelope model of the system is of fifth order (formed by five state equations—Equations (13) and (15)), even though there are three energy storage elements in the system (split DC link capacitors may be considered as a single element). To counteract the inherent model order augmentation imposed by envelope modeling, the slow-varying amplitude derivative and phase (SVADP) methodology [

19] assumes

and combining this with (13)–(15) was adopted in [

11], allowing us to derive a reduced-order envelope model given by

5. Proposed Feedback Control Structure

Defining the right-hand side of (22) as

and rearranging accordingly, the inverse relation between

u(

t) and the inverter switching frequency is given by

indicating the existence of a feedback linearization function. Consequently, a dual-stage control structure consisting of feedback linearization action to cope with (24) and a linear regulator to impose the desired closed-loop dynamics on (23) is proposed. Regarding the former, note that while instantaneous current magnitude and phase, as well as DC link voltage, may be measured in real time, the instantaneous inductance value

L(

t) is non-measurable in real time. Therefore, a nominal known inductance value

L0 is adopted in the controller to form the feedback linearization action as

Applying (25) with (22), there is

In the nominal case (

L(

t) =

L0), (22) reduces to (23) as desired. Otherwise, a nonzero equivalent disturbance function

d(

t) would be acting on the system. In reality, nonzero

d(

t) should always be considered since (22) itself is an approximation. Consequently, an integrator-based linear regulator should be adopted in order to bring the steady-state error to zero. Moreover, adopting zero-crossings-based phase measurement [

11] introduces the half-switching-period delay

Td =

Ts/2 into the system, which must be taken into account during linear regulator design. The overall closed-loop system block diagram is depicted in

Figure 3.

When the feedback linearization action (25) is applied, the dynamics of the current phase are governed by (26). The corresponding closed-loop system block diagram is depicted in

Figure 4 with

C(

s) denoting the transform function of the linear regulator to be designed next.

According to

Figure 4, the loop gain is given by

Adopting a PI controller

as the linear regulator, the loop gain becomes

Denoting the crossover frequency as

ωC, there are

with

PM denoting the corresponding phase margin. Typically,

is selected [

20] so that

is obtained from (30), yielding

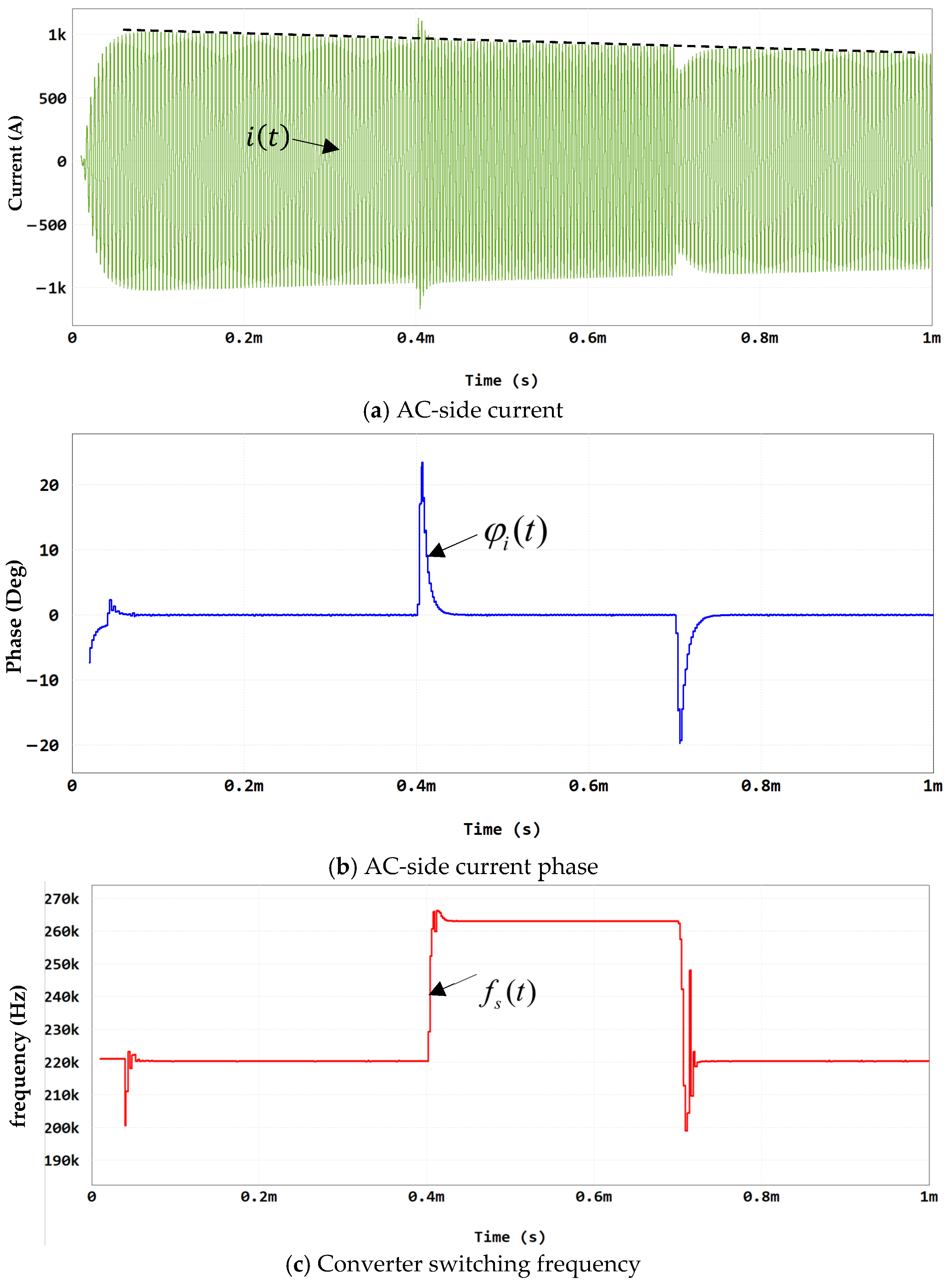

6. Verification

To verify the validity of the proposed control methodology, a component-level switched model of the circuit in

Figure 2 was established using PSIM software (2025a version). Corresponding parameter values are summarized in

Table 1. To obtain the phase, the zero-crossings-based phase measurement approach in [

21] was used in the present work, while phase-detection errors were assumed negligible. The minimum operating frequency of the system was assumed to be

fs,min = 200 kHz, yielding a worst-case delay of

Td,max =

Ts,max/2 = 2.5 μs, yielding a crossover frequency of (cf. (32))

ωC ≈ 2π∙45 [krad/s] with π/4 phase margin. The corresponding Bode diagram is depicted in

Figure 5.

Applying the proposed feedback linearization, the phase dynamics in (26) become linear in the phase variable in the vicinity of resonance. Together with the PI controller, this yields an LTI unity-feedback loop. Closed-loop stability then follows from the Nyquist criterion, evaluated via the above Bode plot; the positive gain and phase margins ensure local stability around the operating point under consideration. Simulations were performed in open-loop at the nominal resonant frequency

and closed-loop, where the inverter current phase was regulated by the proposed controller, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The controller was given a reference phase value

tg(

φi(

t))

* of zero degrees to ensure resonant operation for load power transfer maximization. Six simulation scenarios were conducted with RLC load parameters varied according to (1) with

and

standing for a unity-magnitude step function applied at

, representing the abrupt change in the load components during actual plasma generation within the pulse. Scenarios corresponding to each simulation are given in

Table 2, cf. (35). Corresponding simulation results are shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. Each result consists of three subplots: instantaneous AC-side current, corresponding phase and operating frequency. In addition, the “ideal current envelope” is indicated by a dashed line in the former subplot, demonstrating the theoretical current envelope of a system instantaneously remaining in resonance. When operated at constant frequency, the instantaneous current magnitude drops immediately upon component value variation, accompanied by a sharp phase increase, returning to the original (resonant) state upon nominal component value restoration. On the other hand, it is well evident that the system remains in resonance following step-like variation in RLC load parameters under the proposed control strategy after a short transient.