1. Introduction

Controllability is a fundamental property of dynamical systems and is often regarded as a prerequisite for proper system operation. Classical tests such as the controllability matrix rank condition, the positive definiteness of the controllability Gramian, and the Popov–Belevitch–Hautus (PBH) test are widely used, but they provide only binary information and can be highly sensitive to parameter perturbations in certain conditions [

1]. To overcome these limitations, numerous metrics have been proposed to quantify the degree of controllability (DoC), including controllability norms [

2], extended PBH tests [

3], modal controllability measures [

4], and energy-based characterizations using the minimum 2-norm of uncontrollable initial conditions [

5]. Among these, Gramian-based DoC metrics have become the most prevalent due to their closed-form tractability and direct physical interpretation. Building on the observation that the minimum control energy is intrinsically linked to the controllability Gramian [

6], these metrics have been widely employed and extended beyond standard LTI systems to descriptor systems [

7,

8], nonlinear systems [

9,

10], bilinear systems [

11,

12], and network systems [

13,

14].

One of the most important applications of Gramian-based DoC metrics is optimal actuator placement [

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, conventional DoC measures do not directly address the system’s ability to reject external disturbances, which is often critical in actuator allocation. In practical control systems, external disturbances and cyber–physical uncertainties are inevitable, and numerous controller- and observer-based strategies have been developed to mitigate their effects [

19,

20]. These studies, however, focus on controller synthesis after the actuator configuration has been fixed. In contrast, it is also important to evaluate the inherent disturbance-rejection capability of a system structure itself, independent of any particular controller design, which motivates the development of the disturbance-rejection controllability metric. Early approaches attempted to maximize disturbance rejection using frequency–domain transfer function methods [

21,

22], but these are limited when disturbances span arbitrary frequency ranges. In addition, frequency–domain formulations are inherently restricted to steady-state sinusoidal inputs and rely on spectral representations that do not directly capture broadband disturbances commonly encountered in mechanical systems. Moreover, transfer-function-based formulations are fundamentally limited in extending to multi-input–multi-output (MIMO) systems, since disturbance-rejection characteristics cannot be represented by a single frequency response and depend on the choice of input–output pairs and weighting functions. In contrast, Gramian-based time-domain methods provide a unified and coordinate-invariant framework that naturally accommodates MIMO dynamics. Consequently, the focus of subsequent research has shifted toward time–domain formulations that quantify disturbance rejection through system Gramians, enabling a more general and quantitative characterization of disturbance responses. Mirza and Van Niekerk [

23] proposed a disturbance sensitivity Gramian in the time domain, though its dependence on the feedback gain restricted its applicability. A key advance was made by Kang et al. [

24], who introduced the degree of disturbance rejection (DoDR) metric for open-loop systems, formulated via controllability and disturbance Gramians, and later extended in related studies [

25,

26]. Building on this foundation, Xia et al. [

27] combined DoC and DoDR into a unified Gramian-based framework and applied it to wind turbine systems [

28,

29], while Jeong and Park [

30] extended DoDR concepts to active noise control.

Despite their closed-form tractability, Gramian-based metrics typically require solving differential equations and remain dependent on the final time horizon, motivating the use of algebraic steady-state solutions available only for asymptotically stable systems. For unstable dynamics, prior studies [

17,

31] separated stable and anti-stable contributions, which prevented simultaneous energy characterization. This limitation was resolved by Lee and Park [

32], who derived a unified steady-state DoC metric that accounts for both stable and unstable subsystems, demonstrating that the total control energy equals the sum of subsystem contributions and enabling efficient computation for unstable systems. Building on this framework, subsequent work extended the concept to disturbance-rejection analysis, deriving a steady-state solution of the DoDR metric for unstable systems and thereby enabling a quantitative assessment of disturbance-rejection capability in the presence of unstable modes [

33].

While the aforementioned studies provide meaningful metrics for unstable systems, their applicability is limited to cases where system poles lie strictly in the left- and right-half planes. In particular, these formulations break down when poles are located on the imaginary axis, as in the presence of undamped modes. To address this issue, various approaches have been investigated [

34,

35,

36,

37], most of which introduce small perturbations in the form of artificial light damping to ensure stability of the Gramian-based solutions. However, such methods inherently depend on the structure and magnitude of the artificially added damping, leading to results that lack robustness. More recently, Lee [

38] resolved this limitation by defining the Gramians in the Laplace domain and employing the generalized final value theorem, thereby deriving an exact steady-state DoDR metric without the need for small perturbations. This metric yields accurate disturbance-rejection solutions for undamped flexible structures with nonzero natural frequencies. Nevertheless, it does not account for rigid-body motions, where the natural frequency vanishes and poles reside at the origin. Consequently, the problem of evaluating disturbance-rejection capability in systems with rigid-body modes remains open.

Motivated by these challenges, the present study develops a steady-state formulation of the DoDR metric that remains valid even when a rigid-body mode is present, representing a system with a single zero eigenvalue commonly found in mechanical structures. While previous results have successfully addressed unstable or oscillatory modes, the case of rigid-body dynamics where poles lie at the origin has remained unresolved. The primary novelty of this work lies in the analytical treatment, providing the first closed-form steady-state solution for the DoDR metric in systems that contain a single zero eigenvalue, a case not covered by previous formulations restricted to asymptotically stable systems. The blockwise decomposition and Schur complement framework are employed as analytical tools to systematically characterize the influence of the zero-eigenvalue mode within the overall Gramian structure. The single rigid-body case analyzed in this study represents an initial step toward extending the proposed framework to systems with multiple rigid-body modes, such as flexible multibody structures or large-scale mechanical networks, which will be addressed in future work.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the conventional formulation of the DoDR metric and its steady-state expression for asymptotically stable systems.

Section 3 extends the analysis to systems that include a single rigid-body mode, deriving the closed-form steady-state disturbance-rejection metric through a blockwise Gramian decomposition.

Section 4 presents numerical examples based on mass–spring–damper chains, illustrating both the numerical robustness of the proposed formulation and its implications for actuator placement. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses directions for future research, including extensions to systems with multiple rigid-body modes.

2. Preliminaries

This section provides an overview of the DoDR metric originally proposed by Kang et al. [

24], together with its standard closed-form expression for asymptotically stable systems. We begin by considering a controllable linear time-invariant (LTI) system described by

where

denotes the state vector,

the control input, and

the disturbance. The system matrices

A,

B, and

D are assumed to be constant and of appropriate dimensions.

In practical systems, external disturbances acting on mechanical or control systems generally contain multiple frequency components and may be band-limited rather than perfectly white. However, any such band-limited disturbance can be equivalently represented as the output of an appropriate shaping filter driven by a signal with flat power spectral density. If necessary, this shaping filter can be incorporated into the system dynamics by augmenting the state-space matrices

A and

D. Therefore, without loss of generality, the disturbance

is modeled as a zero-mean Gaussian white noise (GWN) process with correlation function

where

denotes the disturbance covariance. This disturbance modeling approach is consistent with that adopted in the original work, where the concept of the DoDR was first introduced.

The disturbance-rejection controllability metric, referred to as DoDR, is then defined as the minimal control energy required to drive the system from the zero state back to the origin in the presence of the disturbance:

subject to

,

, and the dynamics in (

1). A smaller value of

indicates that less control effort is needed to suppress the disturbance and, hence, the system exhibits superior disturbance-rejection capability.

It is well known that (

3) admits the closed-form solution as given in Kang et al. [

24]

where the matrices

are referred to as the

controllability Gramian and the

disturbance Gramian, respectively.

The matrix

is positive definite for any

under the controllability assumption, ensuring that the inverse in (

4) is well defined. The two Gramians in (

5) and (

6) satisfy the differential Lyapunov equations:

whose solutions directly yield the quantities in (

4).

Although the DoDR provides a meaningful quantitative measure for assessing the disturbance-rejection capability of a system, its computation generally requires solving the differential equations in (

7) and (

8), which can be computationally demanding. In addition, the DoDR expression in (

4) depends explicitly on the final time

t, so its value may vary with the chosen time horizon, making it difficult to obtain a representative performance index for the system. To address both the computational cost and the time-dependence issue, it is common to replace the time-varying formulation (

4) with its steady-state counterpart whenever possible.

The Gramians defined in (

5) and (

6) admit steady-state limits if the system is asymptotically stable, i.e., when

A is a Hurwitz matrix. In that case, the steady-state Gramians

and

satisfy the algebraic Lyapunov equations:

and the steady-state disturbance-rejection metric is then given by

Since the algebraic Equations (

9) and (

10) can be solved directly without integrating the differential Equations (

7) and (

8), the steady-state Formula (

11) avoids the computational burden associated with the original definition (

4). Furthermore, it eliminates the explicit dependence on

t, yielding a time-invariant performance index.

It is important to note, however, that the steady-state Gramians in (

9) and (

10) exist only when all eigenvalues of

A lie in the open left-half complex plane. If

A has eigenvalues at the origin, i.e., the system possesses zero eigenvalue modes such as rigid-body motions, both

and

grow unboundedly as

. Consequently, the steady-state expression (

11) is not applicable when zero eigenvalues are present, and the effect of these modes on the disturbance-rejection metric remains unclear. Motivated by this limitation, the next section develops an alternative formulation of the DoDR that explicitly addresses the case where

A has a single zero eigenvalue mode in addition to asymptotically stable modes. This constitutes the scope of the present paper. Focusing on this simplest scenario allows us to rigorously characterize the Gramian behavior in the presence of a zero eigenvalue, while also laying the foundation for future extensions to cases involving multiple zero eigenvalues.

3. DoDR Formulation for Systems with a Single Zero Eigenvalue

The previous section has shown that the steady-state disturbance-rejection metric admits a closed-form expression when all eigenvalues of the system matrix A lie strictly in the open left-half complex plane. However, when A possesses a single zero eigenvalue, corresponding to a rigid-body mode, the controllability and disturbance Gramians diverge as the time horizon grows, rendering the standard steady-state formula inapplicable. This section develops a formulation of the disturbance-rejection metric that explicitly addresses systems comprising both asymptotically stable modes and a single zero eigenvalue mode. We first represent the Gramians in a blockwise structure according to the spectral decomposition of A, analyze the growth rates of the individual blocks, and show that all cross terms vanish as the time horizon tends to infinity. By introducing a suitable normalization for the zero-eigenvalue block, we then derive a closed-form steady-state expression that characterizes the disturbance-rejection metric in the presence of a single zero eigenvalue.

3.1. Problem Setup and Blockwise Representation

Consider a linear time-invariant system in which the system matrix

A contains both asymptotically stable eigenvalues and a single zero eigenvalue, the latter typically associated with a rigid-body mode. Since the previous section confirmed that the steady-state solution of the DoDR metric exists when

A is Hurwitz, this motivates extending the analysis to the case where

A includes both stable and zero eigenvalue modes. To this end, the system matrix

A is decomposed into two blocks, one corresponding to the stable eigenvalues and the other to the single zero eigenvalue. In general, such a block decomposition can be achieved through a similarity transformation [

39]; therefore, without loss of generality,

A can be represented by a linear transformation of the state vector

x in the block-diagonal form that separates these two types of modes. For simplicity, this paper adopts the following block-diagonal representation of

A without explicitly describing the transformation process. Specifically, let

where

is Hurwitz with

, and

represents the single zero eigenvalue mode. The state, control, and disturbance matrices are partitioned accordingly as

so that the system dynamics can be written in the decoupled form

Since we assumed that

is controllable,

is controllable, and in the single zero eigenvalue case this further implies that

so that

is controllable. This blockwise representation enables us to analyze the controllability and disturbance Gramians on each subspace separately, laying the foundation for deriving a closed-form steady-state disturbance-rejection metric that accounts for both asymptotically stable modes and a single zero eigenvalue mode.

Having introduced the block-diagonal representation (

12)–(

14), we next express the controllability and disturbance Gramians in the same blockwise form. From the definition of the controllability and disturbance Gramians in (

5)–(

6), both Gramians naturally admit a block structure:

where each block is defined as

for

, with the subsystem matrices

,

,

,

,

, and

as defined in (

12) and (

13). The block matrices satisfy the following properties.

Lemma 1 (Convergence of stable-block Gramians).

The block matrices converge as to the unique solutions and of the algebraic Lyapunov equations Proof. Since

is Hurwitz,

exponentially decays to zero, and the integrals defining

and

converge as

. Differentiating

with respect to time gives

whose steady-state solution satisfies the first equation in (

18). An identical argument applies to

. Hence the limits

and

exist and are unique. See also [

24,

39]. □

Lemma 2 (Growth of the zero-eigenvalue block).

Suppose represents the single zero eigenvalue mode. Then, for all , the block matrices simplify to Proof. Since

, the matrix exponential satisfies

Substituting into the definitions of

and

gives

which completes the proof. □

Remark 1. As shown in Lemma 2, the zero-eigenvalue blocks and grow linearly with t according to (20). Since both terms diverge as , the overall controllability Gramian and disturbance Gramian also diverge, which explains why the classical steady-state disturbance-rejection metric cannot be directly applied when a zero eigenvalue mode is present. Lemma 3 (Closed-form limits of off-diagonal blocks).

Under and Hurwitz, the off-diagonal blocks in (15) converge as and admit the closed-form limits: Proof. Consider

. Since

,

. Moreover,

is Hurwitz, so

Hence,

The other blocks follow analogously. Since

and

, their steady-state limits directly yield

and

. □

The preceding lemmas have established the convergence properties of all relevant Gramian blocks: the stable–stable blocks converge to finite steady-state limits, the zero–zero blocks grow linearly with time, and the off-diagonal blocks admit closed-form steady-state limits. Together, these results provide a complete blockwise characterization of the controllability and disturbance Gramians for systems with both asymptotically stable modes and a single zero eigenvalue mode. In the next subsection, we exploit these properties to show that all cross terms vanish as , thereby enabling a closed-form disturbance-rejection metric that incorporates the effect of a single zero eigenvalue mode into the classical formulation.

3.2. Vanishing Cross Terms in the DoDR Expansion

To investigate the asymptotic behavior of the disturbance-rejection metric, we first express the inverse of the controllability Gramian using the blockwise inversion formula based on the Schur complement. Given the block representation of the controllability Gramian in (

15), the inverse

admits the standard block representation shown below. This formulation enables us to separate the contributions of the stable modes, the single zero-eigenvalue mode, and the associated cross terms in the DoDR metric. The inversion follows the standard blockwise inversion formula based on the Schur complement [

40]:

Applying this formula to the controllability Gramian in (

15) yields

where the Schur complement

is given by

Since the system contains a single zero eigenvalue mode, the

block of the controllability Gramian is scalar. Accordingly, the Schur complement

represents the scalar adjustment term arising from this blockwise inversion. In addition, since

and

for any

under controllability, the scalar

is strictly positive. Therefore, its reciprocal

is well-defined. Substituting (

28) into the finite-horizon DoDR expression (

4) and using the blockwise disturbance Gramian in (

15), we expand the trace as follows:

where

This blockwise expansion separates the contributions into the stable term

, the single zero-eigenvalue term

, and the cross terms

. In what follows, we show that all cross terms vanish as

in the single zero-eigenvalue case, which simplifies the disturbance-rejection metric to the remaining main contributions.

Lemma 4 (Vanishing of

).

Let Then Proof. By Lemmas 1 and 3, the factors

,

,

, and

converge to finite limits as

. Hence the scalar

remains bounded and converges to a finite limit. By Lemma 2,

, and therefore

where

is bounded because each of

,

, and

converges to a finite matrix. Consequently,

grows linearly with

t since

is controllable in the single zero-eigenvalue case, implying

. Hence

and

. Combining bounded

with

yields

which proves (

33). □

Corollary 1 (Vanishing of

and

).

Let Then Proof. From Lemmas 1 and 3, the factors

,

,

,

, and

converge to finite limits as

. Hence

remain bounded and converge to finite limits. Since (

35) implies

and therefore

, we obtain

which proves (

38). □

The above results show that all cross terms , , and vanish in the steady state. Consequently, the steady-state value of the disturbance-rejection metric is entirely determined by the two main contributions, and , whose convergence properties and closed-form expressions remain to be analyzed. The next subsection investigates the limits of and , thereby establishing the final closed-form expression of the DoDR metric for systems with a single zero eigenvalue mode.

3.3. Convergence of the Main Terms and Closed-Form Solution of the DoDR Metric

Having established that all cross terms vanish in the steady state, we now focus on the two main contributions, and , which fully determine the steady-state value of the disturbance-rejection metric. This subsection analyzes the convergence properties of these two terms and, through this analysis, derives their limiting behavior as , thereby obtaining closed-form expressions that extend the conventional disturbance-rejection metric to systems with a single zero eigenvalue mode in addition to asymptotically stable modes.

To proceed, we first analyze the individual contributions and in the steady state. The following lemmas establish the convergence of each term and provide the necessary closed-form expressions for the final result.

Lemma 5 (Convergence of

).

Let Then converges to a finite limit as , given by where and are the unique solutions of the Lyapunov equations in (18) Proof. The convergence of

and

was already established in Lemma 1. Since

for all

under controllability,

is also positive definite and

is well-defined. Therefore, it follows that

converges to

as

. This proves (

42). □

Lemma 6 (Convergence of

).

Let where and are defined in (20) and (29), respectively. Then converges to a finite limit as , given by Proof. From Lemma 2, the zero-mode blocks of the Gramians satisfy the linear growth relations in (

20), namely

for all

. As established in Lemma 4 [see (

35)],

can be written as

where

is bounded because each of

,

, and

converges to a finite matrix as

(Lemmas 1 and 3). Since

is controllable in the single zero-eigenvalue case, we have

and thus

. It follows that

grows linearly with

t and satisfies

Combining this with

gives

Taking the limit as

yields

which proves (

44). □

Having established in the preceding lemmas that the cross terms

,

, and

vanish in the steady state and that the remaining terms

and

converge to the closed-form expressions (

42) and (

44), respectively, we are now in a position to combine these results. For the reader’s convenience, the following theorem restates all definitions and assumptions used throughout the paper so that the result is entirely self-contained. It then summarizes the steady-state behavior of the disturbance-rejection metric and provides its closed-form solution for systems with a single zero eigenvalue mode in addition to asymptotically stable modes.

Theorem 1 (Steady-State Solution of the DoDR Metric).

Consider the linear time-invariant system where is the state, the control input, and a zero-mean Gaussian white noise process with covariance . The controllability and disturbance Gramians are defined by The finite-horizon disturbance-rejection metric is which represents the minimal control energy required to steer the state from to over in the presence of disturbances. Assume that is controllable, so that for any , and that a similarity transformation block-diagonalizes the system as where is Hurwitz. Since is controllable, it follows that is controllable and , so that the zero eigenvalue mode is also controllable. Define the steady-state metric Then exists and is given by where and are the unique solutions of the Lyapunov equations Proof. By Lemma 4 and Corollary 1, the cross terms

,

, and

vanish as

. Moreover, Lemmas 5 and 6 give the closed-form limits for

and

. Combining these results with the blockwise expansion of

in (

30) directly yields (

55). □

The closed-form steady-state solution established in Theorem 1 offers several key insights into the disturbance-rejection capability of systems containing both asymptotically stable modes and a single zero eigenvalue mode. First, the derived expression explicitly separates the contributions of the exponentially decaying modes and the linearly growing rigid-body mode, thereby enabling a clear interpretation of how each subsystem influences the overall disturbance-rejection metric. In contrast to the conventional DoDR formulation, which becomes ill-posed in the presence of zero eigenvalues due to the unbounded growth of the Gramians, our result provides a well-defined finite performance index by isolating the dominant linear growth terms and normalizing them appropriately. Consequently, the closed-form solution in (

55) resolves the issue of evaluating disturbance-rejection metrics for systems with rigid-body dynamics, where classical approaches fail to yield meaningful steady-state limits.

In particular, the zero-eigenvalue contribution is given by

which can be interpreted as a

disturbance-to-control transmissibility ratio. It quantifies how strongly disturbances couple into the rigid-body mode relative to how effectively the control input can actuate that mode. A larger disturbance channel

or weaker control channel

increases

, indicating degraded disturbance-rejection capability, whereas stronger actuation along

reduces this term, reflecting improved suppression of rigid-body perturbations. From a design perspective,

therefore provides a direct metric for actuator effectiveness in rigid-body disturbance rejection, complementing the stable-mode contribution:

which is determined by the damping and modal properties of the asymptotically stable subsystem. Together, the two terms define the steady-state metric:

cleanly separating the contributions of stable and rigid-body modes and enabling transparent trade-offs in control design.

Moreover, the availability of an explicit analytical expression eliminates the need for repeated numerical integration of the differential Lyapunov equations, thus significantly reducing the computational cost associated with performance evaluation and controller synthesis. The blockwise characterization also offers structural insights into how the system matrices influence the disturbance-rejection capability, which can be exploited in actuator placement and robust control system design.

To illustrate the practical implications of the proposed metric and to demonstrate how it overcomes the limitations of the standard DoDR formulation, we next present numerical examples. These examples highlight the accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability of the closed-form solution, while validating its consistency with time-domain simulations for systems involving both asymptotically stable modes and a single zero eigenvalue mode.

4. Numerical Examples on Disturbance-Rejection Controllability and Actuator Allocation

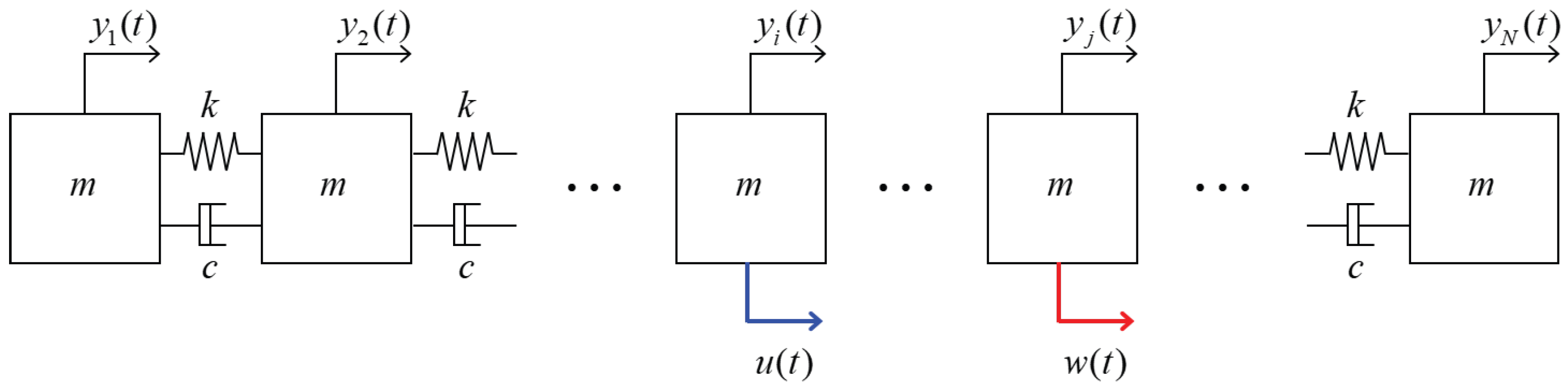

In this section, we investigate the disturbance-rejection controllability of a mass–spring–damper chain with a rigid-body mode, which provides a simple yet insightful testbed for actuator allocation problems. The system consists of N identical masses connected in series by springs and dampers, without any springs or dampers attached to the ground. This configuration inherently yields a rigid-body translational mode in addition to the stable oscillatory modes. We consider an external disturbance acting on a specific mass and examine how the placement of a limited number of actuators affects the steady-state disturbance-rejection metric introduced in the previous sections. Two representative cases are studied: (i) : We demonstrate numerical efficiency and numerical stability advantages of the proposed algebraic steady-state computation over conventional finite-horizon integration. (ii) : Using the proposed steady-state metric, we investigate the actuator placement problem across all candidate sites and interpret the physical plausibility of the selected location.

4.1. System Description

Consider

N masses connected in a one-dimensional chain by linear springs and dampers, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Each mass is constrained to a single translational degree of freedom

, so that the system has

N generalized coordinates. Each spring and damper connects two adjacent masses; thus, no stiffness or damping links to the ground are present, which introduces a rigid-body translational mode in addition to the oscillatory modes. Setting the mass, damping, and stiffness parameters to unity

for simplicity, the equations of motion for the system reduce to

where

is the displacement vector, and the standard tridiagonal damping and stiffness matrices are identical:

The external input

represents actuator forces, while

denotes disturbance inputs. Their distributions across the masses are defined by the matrices

F and

G, respectively, which select the locations of actuators and disturbances as canonical basis vectors.

Defining the state vector

the system (

61) can be written in the state-space form

with

Because no springs or dampers connect the chain to a fixed point, the matrix

always contains a pair of zero eigenvalues, corresponding to the rigid-body translational mode.

4.2. Numerical Efficiency and Stability Comparison ()

We consider the free–free two-mass chain with

and the state vector

. In this case, the stiffness and damping matrices are identical and given by

We apply the block-orthonormal modal transform

with the mass-orthonormal eigenmatrix

Defining the modal coordinates

with

, the dynamics decouple into an oscillatory mode

and a rigid-body mode

. In particular,

corresponds to the relative displacement between the two masses, while

represents their common translation.

Since

corresponds to a pure translational motion that does not influence the internal dynamics, it is excluded from the state definition to maintain a single zero-eigenvalue mode associated with the rigid-body motion. Accordingly, the state vector is defined as

which represents the essential dynamic variables capturing both the oscillatory mode

and the rigid-body velocity

. This formulation ensures that the system retains only one rigid-body degree of freedom, consistent with the single zero-eigenvalue assumption considered throughout this study. This reduction yields the block-diagonal form in (

14):

If we define the input matrices

and the disturbance matrices

as those corresponding to the force input at the

i-th location and the disturbance at the

j-th location, respectively, we obtain

Partitioning into the stable and zero-eigenvalue blocks consistent with (

12) and (

13), we have

Following these matrices, we evaluate the disturbance-rejection controllability using two approaches. First, the

conventional finite-horizon DoDR is computed by integrating the differential Lyapunov equations in (

7)–(

8) and then applying (

4); the matrix ODEs are integrated with a classical fourth-order Runge–Kutta (RK4) scheme. Second, the

proposed steady-state DoDR is obtained directly from the closed-form expression in Theorem 1 (see (

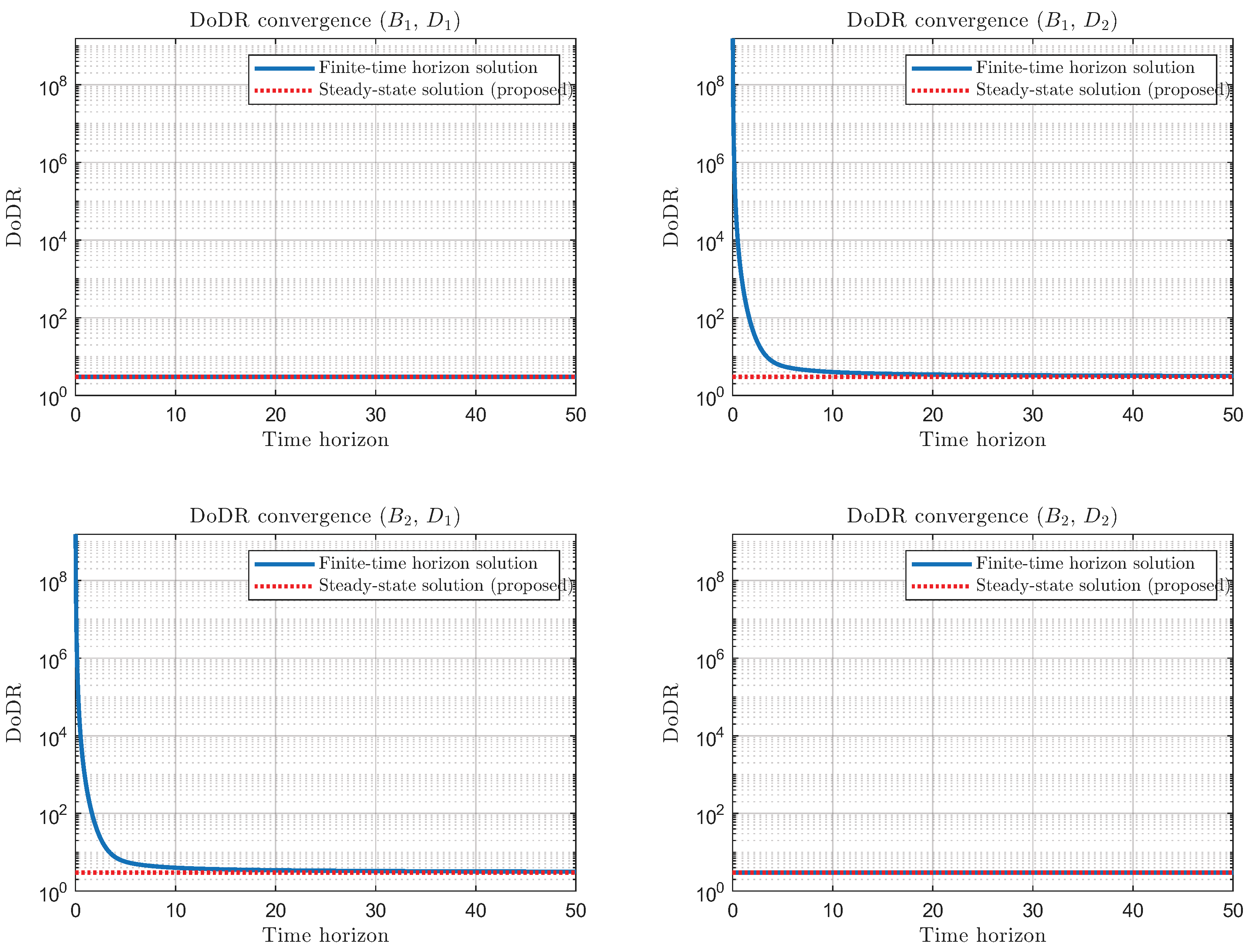

55)). The results are shown in

Figure 2. For the input–disturbance pairs

and

, the controllability and disturbance Gramians are identical, and thus, the finite-horizon DoDR coincides with the steady-state value immediately. For the remaining cases, the finite-horizon DoDR trajectories gradually converge to the steady-state values predicted by our formula as the horizon increases, confirming that the proposed expression exactly captures the steady-state limit of the conventional DoDR.

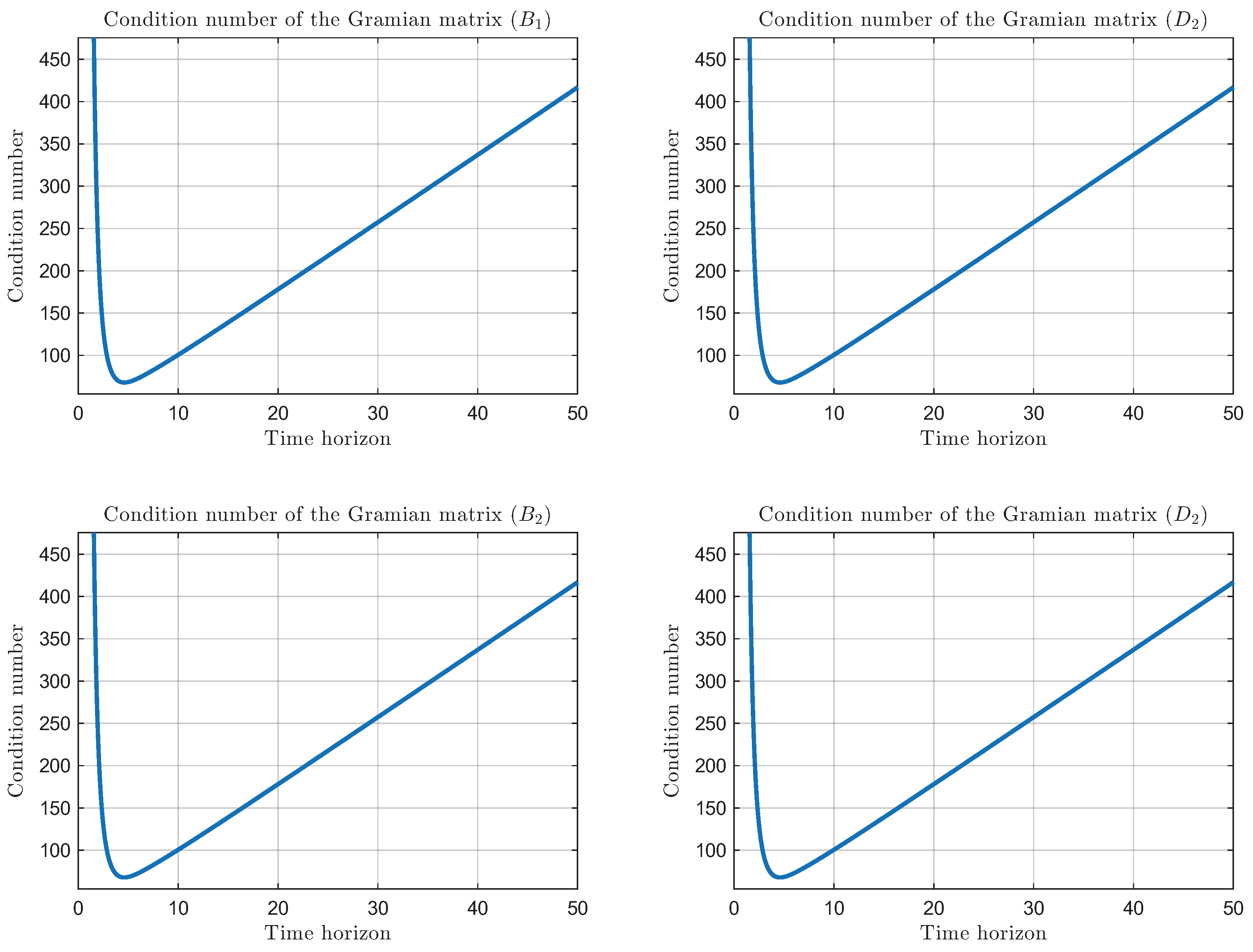

The numerical advantages of the proposed expression are illustrated in

Figure 3. At the beginning of the integration, i.e., for small horizon times, the condition numbers are inevitably large due to transient effects. In cases where the solution truly converges, one would expect the condition numbers to eventually settle to bounded values. However, as seen in the figure, beyond a certain horizon the condition numbers instead grow linearly with time, reflecting the divergence induced by the rigid-body mode. Because the rigid-body mode induces linear growth of the zero-block Gramians, the condition numbers of both

and

deteriorate with time. This ill-conditioning can severely affect the computation of

required by the finite-horizon Formula (

4). In contrast, the proposed steady-state DoDR is obtained from purely algebraic closed forms that remain well-conditioned, yielding the exact steady-state value

without inverting poorly conditioned time-varying Gramians. Hence, for systems with a rigid-body mode, the steady-state formulation is advantageous both in

accuracy (exact asymptotic value) and

numerical robustness (no large-

t ill-conditioning).

4.3. Actuator Placement and Interpretation of Results ()

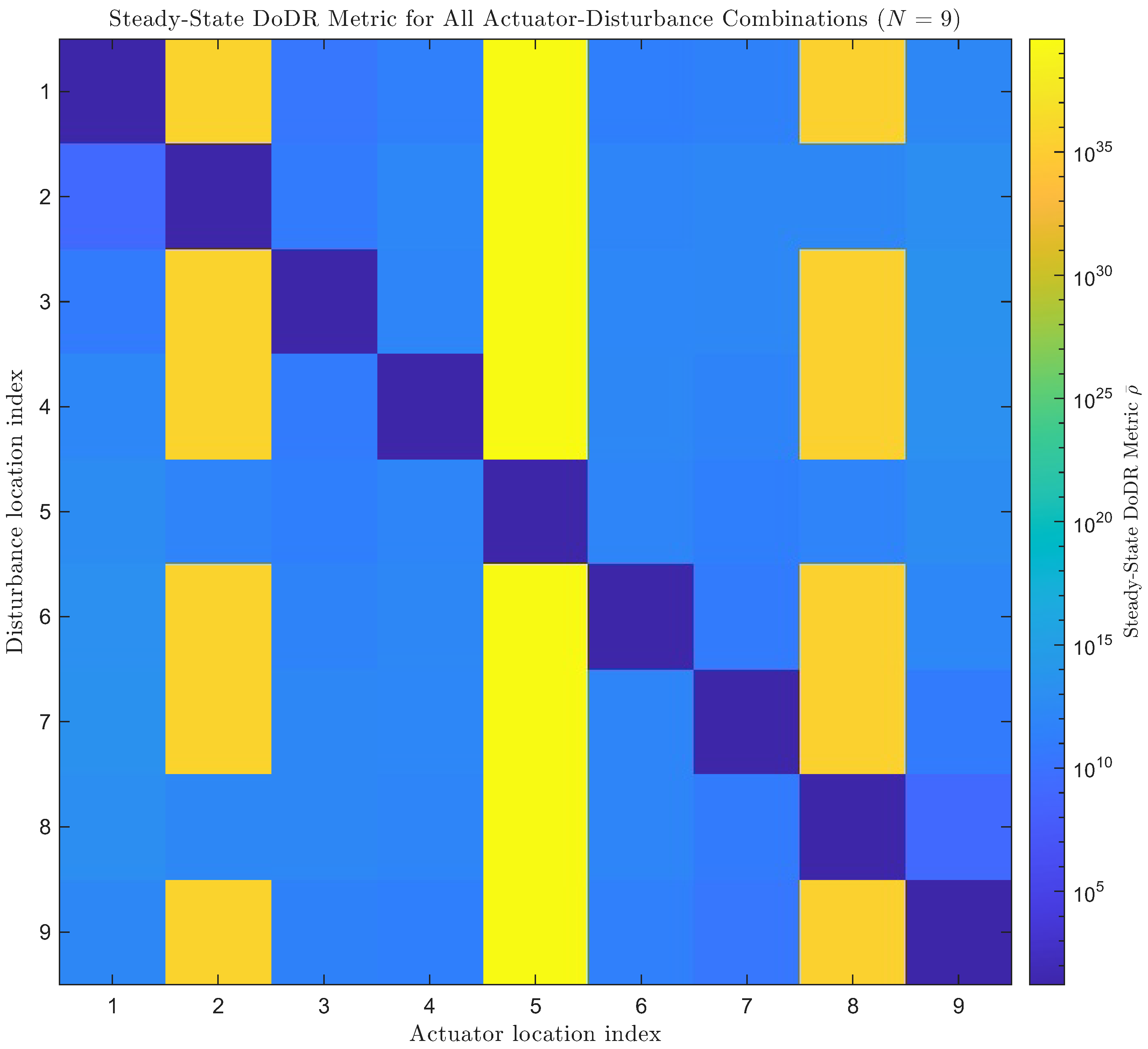

In this subsection, we extend the analysis to a nine-mass chain to examine actuator placement under more complex modal interactions. Having already confirmed in the two-mass case that the proposed steady-state formulation provides both numerical accuracy and robustness, we now demonstrate that the method can be applied without difficulty to higher-dimensional systems. Specifically, we consider nine distinct disturbance scenarios, each corresponding to a unit disturbance applied to one of the masses. For each disturbance case, the proposed steady-state disturbance-rejection metric is evaluated across all nine candidate actuator locations, yielding a total of combinations. This comprehensive set of results enables us to systematically compare the effectiveness of different actuator placements. Based on the computed metrics, we identify locations that provide superior disturbance-rejection controllability as well as those that lead to poor performance, and we interpret these findings in relation to the underlying structural dynamics of the chain system.

The computed values of the proposed metric for all 81 input–disturbance combinations are summarized in

Figure 4. In this figure, the horizontal axis corresponds to the actuator index, indicating the mass location

i where the input matrix

is applied. The vertical axis represents the disturbance index, indicating the mass location

i where the disturbance matrix

acts. The metric values are visualized using a colormap, with the accompanying color bar indicating the magnitude of the steady-state disturbance-rejection metric. This representation allows for a direct comparison of actuator effectiveness across all candidate placements under different disturbance scenarios.

The most immediate observation from

Figure 4 is that the smallest metric values are obtained in the

matched disturbance cases, where the actuator is placed at the same location as the disturbance. Since the DoDR metric is defined as the minimal control energy required for disturbance rejection, this behavior clearly indicates that matched placement provides the most favorable configuration for disturbance suppression. This trend is also consistent with results reported in the literature on finite-horizon DoDR formulations [

24]. Hence, the steady-state DoDR confirms the physically intuitive conclusion that the optimal actuator location is exactly the disturbance location.

Across almost all disturbance scenarios, the least effective actuator position is the 5th mass. This is because the 5th position coincides with the nodal point of the first oscillatory mode (excluding the rigid-body mode). When the actuator is placed at this location, the dominant first mode cannot be effectively controlled, making disturbance rejection particularly difficult. However, when the disturbance itself acts on the 5th mass, the matched condition again yields a small metric value. This can be explained by the fact that no significant excitation of the first mode occurs when the disturbance is applied at its nodal point.

In addition to the 5th mass, actuator placements at the 2nd and 8th masses also yield relatively large metric values. These positions are near the nodal points of the second mode, which is the next dominant oscillatory mode of the chain. This explains why the disturbance suppression capability is reduced when actuators are placed at these locations. A notable feature, however, is observed when the disturbance is applied at these nodal positions (i.e., at masses 2, 5, or 8). In such cases, actuator placements at other nodal positions may still result in comparatively small metric values. For example, when the disturbance acts at the 2nd mass, placing the actuator at the 8th mass yields a lower metric than expected. This occurs because both positions are ineffective in exciting the second mode, so the disturbance itself excites little of the mode that would otherwise be difficult to control. A similar interpretation applies to the cases where disturbances act at the 5th or 8th masses.

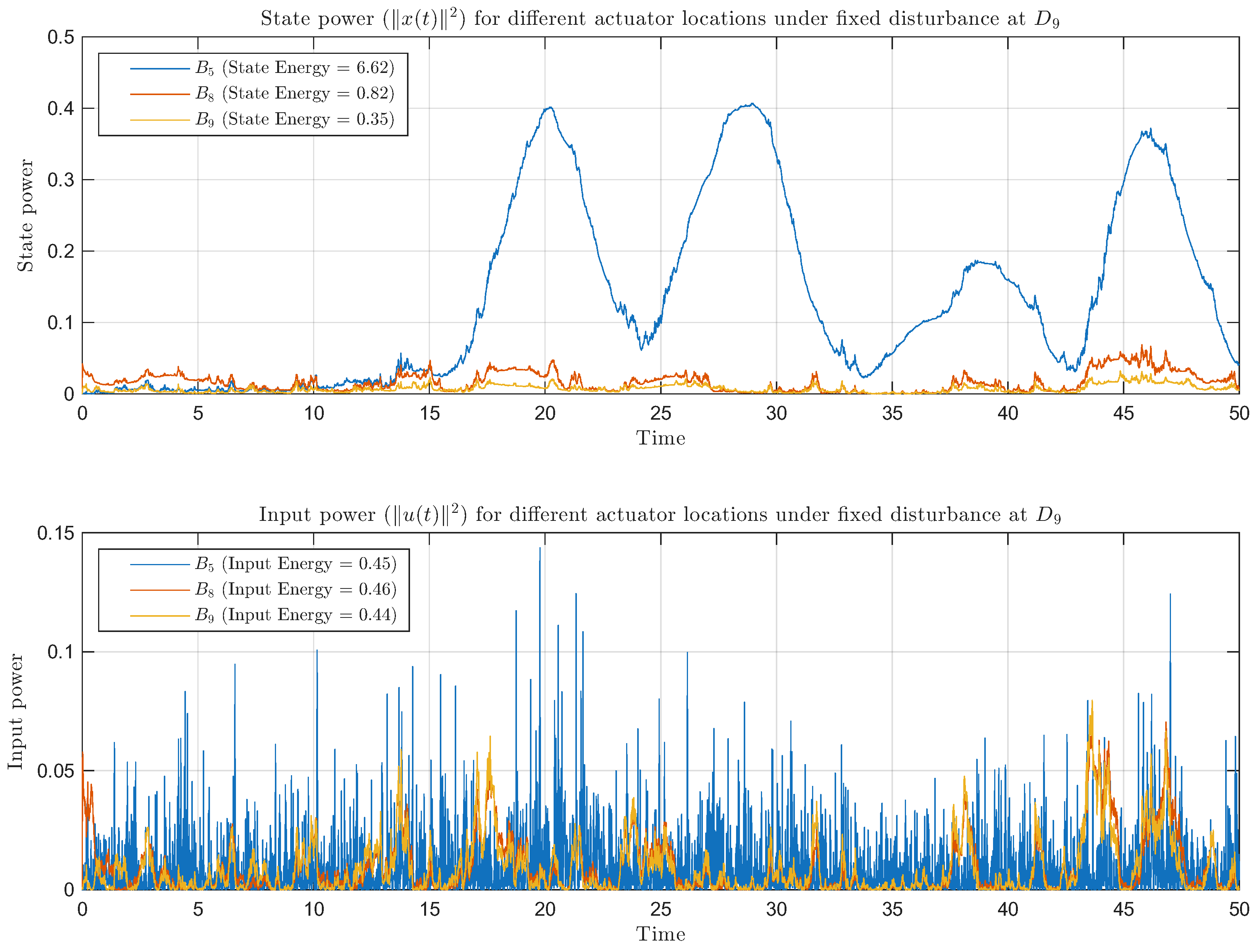

To verify the validity of the DoDR-based actuator placement results presented in

Figure 4, additional simulations were conducted to evaluate the actual control performance under disturbance conditions. The disturbance was applied at the 9th mass location (

), and three actuator configurations were considered: actuators placed at the 5th, 8th, and 9th mass positions (

,

, and

), respectively. As shown in

Figure 4, the DoDR metric predicts that the optimal actuator location is

, while

corresponds to the lowest disturbance-rejection capability. To examine whether these predictions are consistent with closed-loop performance, a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) controller was implemented for each configuration. The weighting matrices of the LQR were adjusted such that the overall input energy remained comparable across cases, allowing a fair comparison of control effectiveness.

Figure 5 illustrates the time histories of the state power

and input power

. The results clearly show that the actuator at

achieves the lowest state power and hence the strongest disturbance suppression, followed by

and

, in agreement with the DoDR predictions. These results confirm that the proposed DoDR metric consistently reflects the system’s actual disturbance-rejection performance observed in time-domain control simulations.

All these results are physically consistent and provide clear evidence that the proposed steady-state DoDR not only guarantees numerical robustness in the presence of rigid-body modes but also yields actuator placement outcomes that are physically meaningful. This demonstrates the practical utility of the proposed formulation in guiding actuator placement decisions for systems that include rigid-body dynamics.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

This study presented a steady-state formulation of the disturbance-rejection controllability (DoDR) metric for LTI systems with both asymptotically stable modes and a rigid-body mode. By exploiting a blockwise decomposition of the system dynamics, we established the asymptotic behavior of the controllability and disturbance Gramians and derived a closed-form steady-state solution. The resulting expression separates the contributions of the stable subsystem and the rigid-body mode, yielding a finite and computationally efficient performance index even when the conventional DoDR becomes ill-posed. This closed-form characterization also provides a clear physical interpretation: the rigid-body contribution appears as a disturbance-to-control transmissibility ratio, while the stable-mode contribution reflects the modal damping properties.

Numerical examples with mass–spring–damper chains demonstrated both the accuracy and physical validity of the proposed metric. In the two-mass case, the steady-state formulation reproduced the exact limit of the finite-horizon DoDR while avoiding numerical ill-conditioning. In the nine-mass case, actuator placement analysis revealed results consistent with modal structures, such as identifying nodal positions as unfavorable actuator sites. The proposed steady-state DoDR formulation was further validated through simulation, where the quantitatively evaluated disturbance-rejection capability showed consistent trends with the predicted DoDR values. This confirms that the DoDR metric enables a reliable quantitative assessment of disturbance suppression performance based solely on system characteristics. These findings confirm that the proposed steady-state DoDR not only ensures numerical robustness but also offers meaningful guidance for actuator placement in systems involving rigid-body dynamics.

The present work focused on systems with a single zero eigenvalue mode. A natural extension is to generalize the analysis to systems with multiple rigid-body modes, which frequently arise in flexible multibody dynamics and aerospace structures. In such cases, the zero-eigenvalue subspace becomes multidimensional, and the corresponding sub-blocks of the controllability and disturbance Gramians exhibit coupled growth patterns rather than the scalar behavior analyzed here. Extending the steady-state DoDR formulation to this setting requires treating the submatrices as multi-dimensional zero-mode blocks and analyzing the asymptotic behavior of their Schur complements. Although the closed-form expressions derived in this paper no longer hold directly, the same blockwise decomposition principle can be applied to derive generalized DoDR metrics for systems with multiple zero eigenvalues. Building upon the framework developed here, future research will address these blockwise behaviors and derive corresponding steady-state expressions for the DoDR metric, thereby broadening the applicability of the proposed approach.