Biofilm Production Ability, Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Staphylococcus aureus from Various Veterinary Hospitals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Prevalence of S. aureus

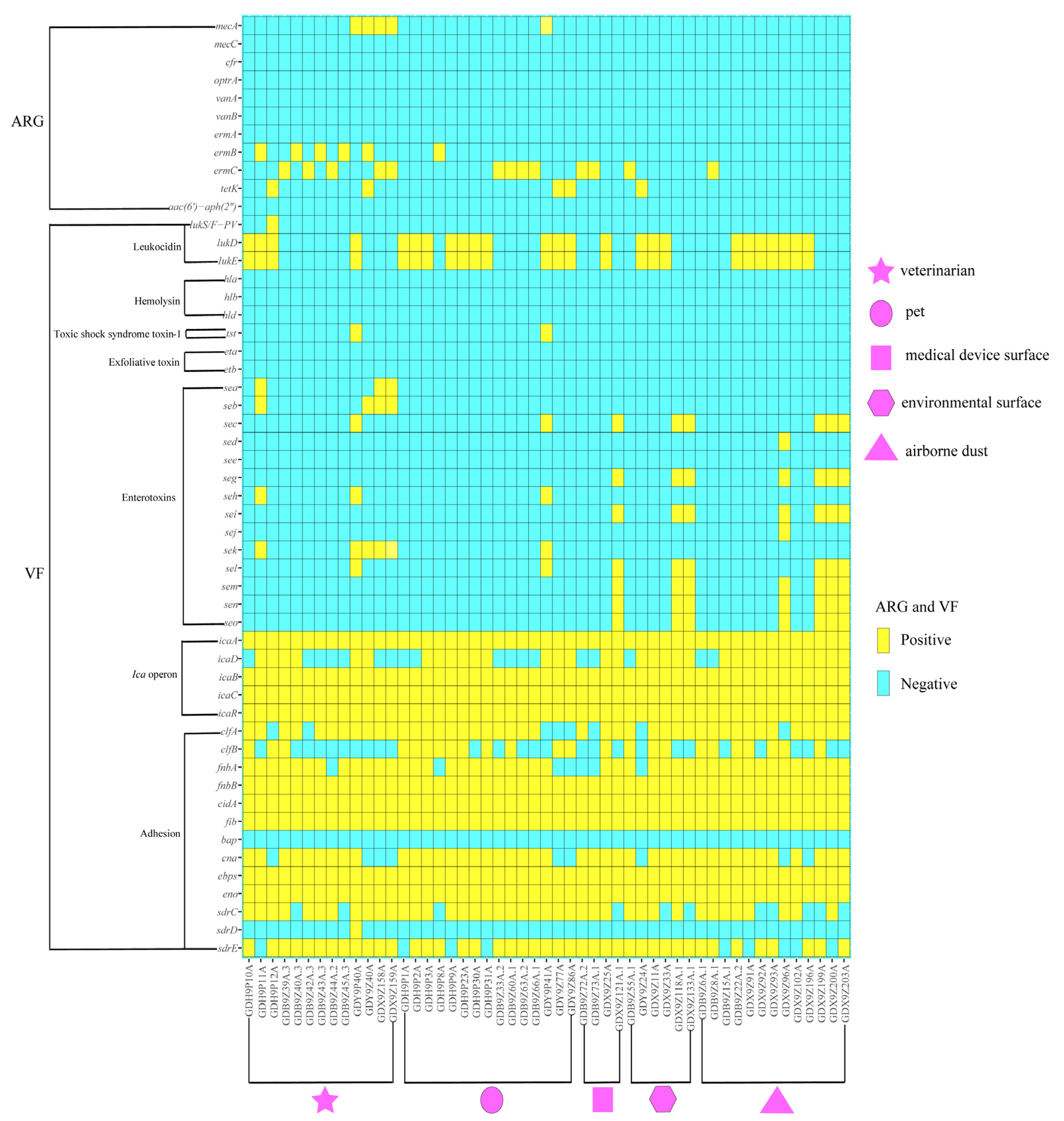

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Antibiotic Resistance Genes

2.3. Virulence Gene Profiles

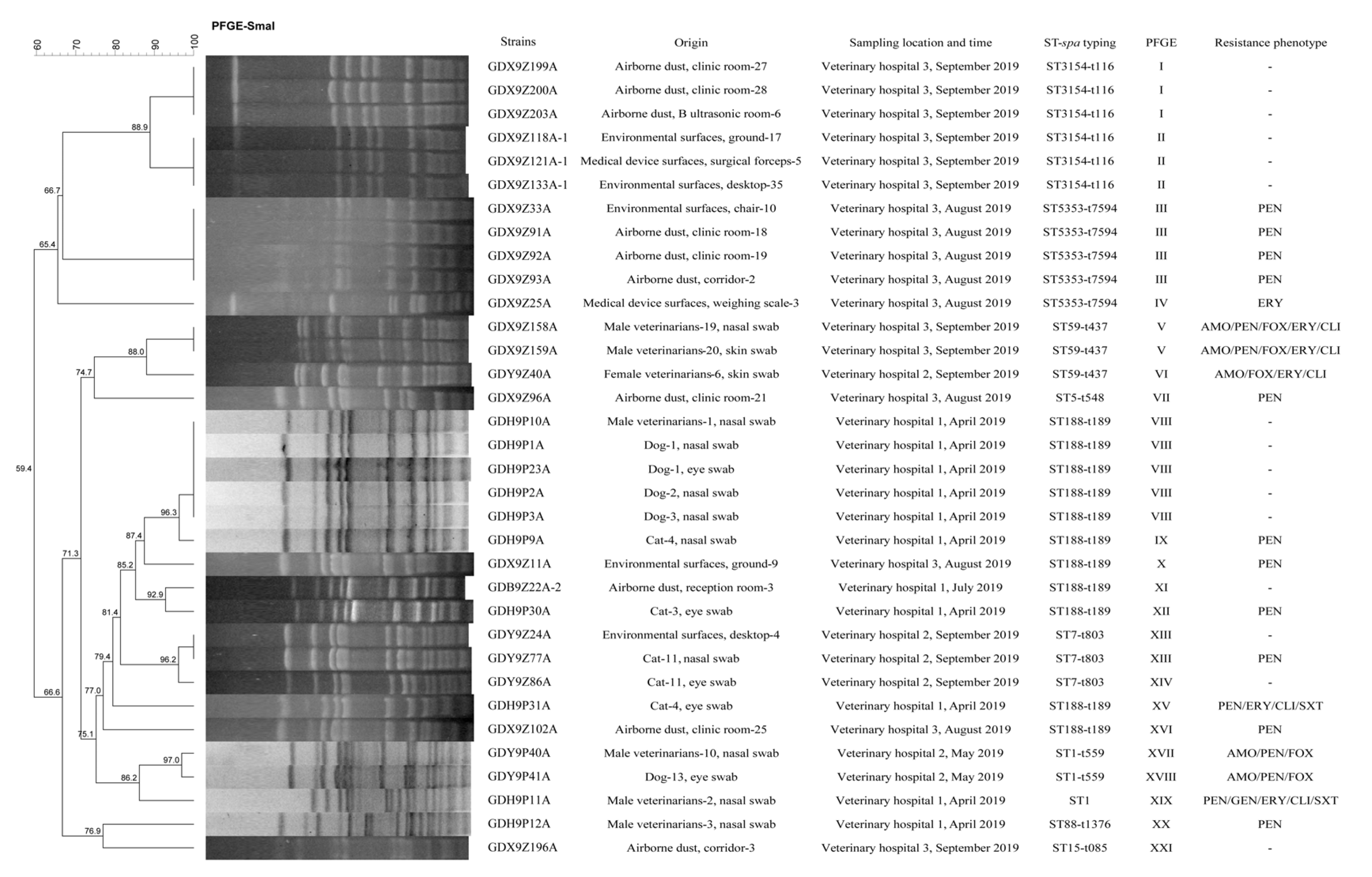

2.4. Molecular Typing and Biofilm Production Ability of S. aureus

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Approval

4.2. Sample Collection

4.3. Sample Processing and Bacterial Isolation

4.4. DNA Extraction and Molecular Identification of S. aureus

4.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.6. Molecular Detection of Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

4.7. Molecular Epidemiology Analysis

4.8. Identification of Biofilm production Ability of S. aureus

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wertheim, H.F.L.; Melles, D.C.; Vos, M.C.; Van Leeuwen, W.; Van Belkum, A.; Verbrugh, H.A.; Nouwen, J.L. The nasal carriage in Staphyloccocus aureus infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hal, S.J.; Jensen, S.O.; Vaska, V.L.; Espedido, B.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Gosbell, I.B. Predictors of mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 362–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chambers, H.F.; Deleo, F.R. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, A.; Diep, B.A.; Mai, T.T.; Vo, N.H.; Warrener, P.; Suzich, J.; Stover, C.K.; Sellman, B.R. Differential expression and roles of Staphylococcus aureus virulence determinants during colonization and disease. MBio 2015, 6, e02272-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stein, R.A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-the new zoonosis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 13, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aklilu, E.; Zakaria, Z.; Hassan, L.; Chen, H.C. Molecular relatedness of methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates from staff, environment and pets at University Veterinary Hospital in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weese, J.S.; Dick, H.; Willey, B.M.; McGeer, A.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Innis, B.; Low, D.E. Suspected transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus between domestic pets and humans in veterinary clinics and in the household. Vet. Microbiol. 2006, 115, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Hao, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.Y.; Logue, C.M.; Wang, B.; Yang, J.; Shen, J.Z.; Wu, C.M. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from pet animals and veterinary staff in China. Vet. J. 2011, 190, e125–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierowiec, K.; Ploneczka-Janeczko, K.; Rypula, K. Cats and dogs as a reservoir for Staphylococcus aureus. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 2014, 68, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, P.G.; Mork, R.L.; Boyle, M.G.; Muenks, C.E.; Morelli, J.J.; Thompson, R.M.; Sullivan, M.L.; Gehlert, S.J.; Merlo, J.R.; McKenzie, M.G.; et al. Interplay of personal, pet, and environmental colonization in households affected by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. 2019, 78, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthing, K.A.; Brown, J.; Gerber, L.; Trott, D.J.; Abraham, S.; Norris, J.M. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci amongst veterinary personnel, personnel-owned pets, patients and the hospital environment of two small animal veterinary hospitals. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 223, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loncaric, I.; Lepuschitz, S.; Ruppitsch, W.; Trstan, A.; Andreadis, T.; Bouchlis, N.; Marbach, H.; Schauer, B.; Szostak, M.P.; Fessler, A.T.; et al. Increased genetic diversity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from companion animals. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 235, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Y.; Tian, D.; Zhang, B. Incidence of surgical-site infection following open reduction and internal fixation of a distal femur fracture. Medicine 2019, 98, e14547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweba, C.C.; Zishiri, O.T.; El Zowalaty, M.E. Isolation and Molecular Identification of Virulence, Antimicrobial and Heavy Metal Resistance Genes in Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pathogens 2019, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klein, E.Y.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Martinez, E.M.; Pant, S.; Gandra, S.; Levin, S.A.; Goossens, H.; Laxminarayan, R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E3463–E3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Gandra, S.; Ashok, A.; Caudron, Q.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: An analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, S.R.; Shrivastava, P.S.; Ramasamy, J. Responding to the challenge of antibiotic resistance: World Health Organization. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2018, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartari, E.; Abbas, M.; Pires, D.; de Kraker, M.E.A.; Pittet, D. World Health Organization Save Lives: Clean Your Hands global campaign-‘Fight antibiotic resistance-it’s in your hands’. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 596–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gandolfi-Decristophoris, P.; Regula, G.; Petrini, O.; Zinsstag, J.; Schelling, E. Prevalence and risk factors for carriage of multi-drug resistant Staphylococci in healthy cats and dogs. J. Vet. Sci. 2013, 14, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guardabassi, L.; Schwarz, S.; Lloyd, D.H. Pet animals as reservoirs of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, N.K.; Mazaitis, M.J.; Costerton, J.W.; Leid, J.G.; Powers, M.E.; Shirtliff, M.E. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: Properties, regulation, and roles in human disease. Virulence 2011, 2, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moormeier, D.E.; Bayles, K.W. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm: A complex developmental organism. Mol. Microbiol. 2017, 104, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pinto, R.M.; Lopes-de-Campos, D.; Martins, M.C.L.; Van Dijck, P.; Nunes, C.; Reis, S. Impact of nanosystems in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms treatment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 43, 622–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cramton, S.E.; Gerke, C.; Schnell, N.F.; Nichols, W.W.; Gotz, F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 5427–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Q.; Xie, S.M.; Lou, X.Q.; Cheng, S.; Liu, X.D.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, Z.B.; Wang, H.Q. Biofilm formation and prevalence of adhesion genes among Staphylococcus aureus isolates from different food sources. Microbiologyopen 2020, 9, e00946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boda, S.K.; Broda, J.; Schiefer, F.; Weber-Heynemann, J.; Hoss, M.; Simon, U.; Basu, B.; Jahnen-Dechent, W. Cytotoxicity of Ultrasmall Gold Nanoparticles on Planktonic and Biofilm Encapsulated Gram-Positive Staphylococci. Small 2015, 11, 3183–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Yang, L.; Hou, Y.C.; Soteyome, T.; Zeng, B.; Su, J.Y.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Chen, D.Q.; Li, Y.Y.; et al. Transcriptomics Study on Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Under Low Concentration of Ampicillin. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shukla, S.K.; Karow, M.E.; Brady, J.M.; Stemper, M.E.; Kislow, J.; Moore, N.; Wroblewski, K.; Chyou, P.-H.; Warshauer, D.M.; Reed, K.D.; et al. Virulence genes and genotypic associations in nasal carriage, community-associated methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant USA400 Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3582–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alonzo, F., 3rd; Torres, V.J. The bicomponent pore-forming leucocidins of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2014, 78, 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tacconelli, E.; Foschi, F. Does gender affect the outcome of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boost, M.; O’Donoghue, M.; James, A. Investigation of the role of dogs as reservoirs of Staphylococcus aureus and the transmission of strains between pet owners and their dogs. Hong Kong Med. J. 2008, 14, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Youn, J.H.; Park, Y.H.; Hang’ombe, B.; Sugimoto, C. Prevalence and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from companion animals and environment in the veterinary teaching hospital in Zambia, Africa. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 37, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanselman, B.A.; Kruth, S.A.; Rousseau, J.; Weese, J.S. Coagulase positive staphylococcal colonization of humans and their household pets. Can. Vet. J. 2009, 50, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.C.; Worthing, K.A.; Ward, M.P.; Norris, J.M. Commensal Staphylococci Including Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Dogs and Cats in Remote New South Wales, Australia. Microb. Ecol. 2019, 79, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drougka, E.; Foka, A.; Koutinas, C.K.; Jelastopulu, E.; Giormezis, N.; Farmaki, O.; Sarrou, S.; Anastassiou, E.D.; Petinaki, E.; Spiliopoulou, I. Interspecies spread of Staphylococcus aureus clones among companion animals and human close contacts in a veterinary teaching hospital. A cross-sectional study in Greece. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 126, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, A.; Caruso, M.; Normanno, G.; Latorre, L.; Miccolupo, A.; Fraccalvieri, R.; Intini, F.; Manginelli, T.; Santagada, G. MRSA in swine, farmers and abattoir workers in Southern Italy. Food Microbiol. 2019, 82, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciandrini, E.; Morroni, G.; Cirioni, O.; Kamysz, W.; Kamysz, E.; Brescini, L.; Baffone, W.; Campana, R. Synergic combinations of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) against biofilms of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) on polystyrene and medical devices. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharsa, H.; Ben Slama, K.; Gomez-Sanz, E.; Lozano, C.; Zarazaga, M.; Messadi, L.; Boudabous, A.; Torres, C. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus from nasal samples of healthy farm animals and pets in Tunisia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, T.; Xu, K.; Li, C.; Li, Y. Molecular characteristics and virulence gene profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Hainan, China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Schwarz, S.; Wang, S.L.; Chen, L.R.; Wu, C.M.; Shen, J.Z. Investigation of a multiresistance gene cfr that fails to mediate resistance to phenicols and oxazolidinones in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, R.; Zhao, L.N.; Du, P.C.; Luo, H.P.; Ren, X.; Lu, P.; Cui, S.H.; Luo, Y.P. Characterization of an Oxacillin-Susceptible mecA-Positive Staphylococcus aureus Isolate from an Imported Meat Product. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019, 26, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.Y.; Liu, Q.; Gao, Q.Q.; Lu, H.Y.; Meng, H.W.; Xie, Y.H.; Huang, Q.; Ma, X.W.; Wang, H.; et al. Phylogenetic analysis and virulence determinant of the host-adapted Staphylococcus aureus lineage ST188 in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.; Qian, S.Y.; Yao, K.H.; Wang, L.J.; Liu, Y.C.; Dong, F.; Song, W.Q.; Zhen, J.H.; Zhou, W.; Xu, H.; et al. Multiresistant ST59-SCCmec IV-t437 clone with strong biofilm-forming capacity was identified predominantly in MRSA isolated from Chinese children. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moremi, N.; Mshana, S.E.; Kamugisha, E.; Kataraihya, J.; Tappe, D.; Vogel, U.; Lyamuya, E.F.; Claus, H. Predominance of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus-ST88 and new ST1797 causing wound infection and abscesses. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2012, 6, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeda, K.; Nakamura, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Nishina, N.; Yasufuku, K.; Hirai, Y.; Hirayama, T.; Goto, K.; Hase, A.; Ogasawara, J. Molecular and epidemiological characterization of staphylococcal foodborne outbreak of Staphylococcus aureus harboring seg, sei, sem, sen, seo, and selu genes without production of classical enterotoxins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 256, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Li, J.; Qiao, M.F.; Meng, D.; Meng, Q.L.; Qiao, J.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, L.X.; Cai, K.J.; Zhang, J.S.; et al. Characteristic profiles of biofilm, enterotoxins and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from dairy cows in Xinjiang Province, China. J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 20, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahfoozi, A.; Shirzad-Aski, H.; Kaboosi, H.; Ghaemi, E.A. Identification of the classical enterotoxin genes of Staphylococcus aureus in various foods by multiplex PCR assay. Iran. J. Vet. Res. 2019, 20, 209–212. [Google Scholar]

- Azara, E.; Longheu, C.; Sanna, G.; Tola, S. Biofilm Formation and virulence factor analysis of Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected from ovine mastitis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hait, J.; Tallent, S.; Melka, D.; Keys, C.; Bennett, R. Prevalence of enterotoxins and toxin gene profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from a bakery involved in a second staphylococcal food poisoning occurrence. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.; Sudagidan, M.; Muratoglu, K. Prevalence of staphylococcal enterotoxins, toxin genes and genetic-relatedness of foodborne Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in the Marmara region of Turkey. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 148, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azmi, K.; Qrei, W.; Abdeen, Z. Screening of genes encoding adhesion factors and biofilm production in methicillin resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Palestinian patients. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoramian, B.; Jabalameli, F.; Niasari-Naslaji, A.; Taherikalani, M.; Emaneini, M. Comparison of virulence factors and biofilm formation among Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from human and bovine infections. Microb. Pathog. 2015, 88, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Zeng, P.; Li, J. Characterization of adhesin genes, staphylococcal nuclease, hemolysis, and biofilm formation among Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from different sources. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013, 10, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Sanchez, D.; Habimana, O.; Holck, A. Impact of food-related environmental factors on the adherence and biofilm formation of natural Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Curr. Microbiol. 2013, 66, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Emaneini, M.; Khoramrooz, S.S.; Shahsavan, S.; Dabiri, H.; Jabalameli, F. Prevalence of panton-valentine leucocidin and phenotypic and genotypic characterization of biofilm formation among Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from children with adenoid hypertrophy. Microb. Pathog. 2015, 89, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, F.; Katouli, M.; Karimi, S. Biofilm production among methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from catheterized patients with urinary tract infection. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 98, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibbern, A.G.; Botaro, B.G.; Viziack, M.P.; Silva, L.F.; Santos, M.V. Evaluation of methods of DNA extraction from Staphylococcus aureus in milk for use in real-time PCR. Genet Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI]. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; CLSI Document M100-S29; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI]. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests For bacteria Isolated from Animals; Approved Standard; VET01-A4/VET01-S2; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tenover, F.C.; Arbeit, R.D.; Goering, R.V.; Mickelsen, P.A.; Murray, B.E.; Persing, D.H.; Swaminathan, B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: Criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 2233–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antoci, E.; Pinzone, M.R.; Nunnari, G.; Stefani, S.; Cacopardo, B. Prevalence and molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among subjects working on bovine dairy farms. Infez Med. 2013, 21, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Armand-Lefevre, L.; Ruimy, R.; Andremont, A. Clonal comparison of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from healthy pig farmers, human controls, and pigs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.; Zeighami, H.; Haghi, F. Molecular Characterization of Methicillin and Vancomycin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains Isolated from Hospitalized Patients. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 1529–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sampling Location | Veterinary Hospital 1 a | Veterinary Hospital 2 b | Veterinary Hospital 3 c | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veterinarians | 9/11 | 2/13 | 2/17 | 13/41 |

| Male veterinarians | 7/7 | 1/7 | 2/7 | 10/21 |

| Skin swabs | 2/2 | 0/2 | 1/2 | 3/10 |

| Nasal swabs | 5/5 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 7/11 |

| Female veterinarians | 2/4 | 1/6 | 0/10 | 3/20 |

| Skin swabs | 2/2 | 1/4 | 0/8 | 3/14 |

| Nasal swabs | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/6 |

| Pets | 11/32 | 3/38 | 0/12 | 14/82 |

| Dogs | 8/24 | 1/14 | 0/6 | 9/44 |

| Eye swab | 4/12 | 1/7 | 0/3 | 5/22 |

| Nasal swab | 4/12 | 0/7 | 0/3 | 4/22 |

| Cats | 3/8 | 2/24 | 0/6 | 5/38 |

| Eye swab | 2/4 | 1/12 | 0/3 | 3/19 |

| Nasal swab | 2/4 | 1/12 | 0/3 | 2/19 |

| Medical device surfaces | 2/3 | 0/11 | 2/23 | 4/37 |

| Infusion pump | - | 0/7 | 0/13 | 0/20 |

| Weighing scale | - | 0/2 | 1/4 | 1/6 |

| Surgical forceps | 1/2 | 0/1 | 1/3 | 2/6 |

| Surgical scissors | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 1/5 |

| Environmental surfaces | 1/18 | 1/38 | 4/82 | 6/138 |

| Desktop | 0/2 | 1/13 | 1/25 | 2/40 |

| Chair | - | 0/8 | 1/19 | 1/27 |

| Cage interior | 1/14 | 0/4 | 0/5 | 1/23 |

| Ground | 0/2 | 0/4 | 2/13 | 2/19 |

| Door handle | - | 0/7 | 0/11 | 0/18 |

| Switch | - | - | 0/7 | 0/7 |

| Drawer | - | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/4 |

| Airborne dust | 4/24 | 0/13 | 9/31 | 13/68 |

| Clinic room | 2/12 | 0/5 | 6/13 | 8/30 |

| Inpatient department | 1/8 | - | 0/5 | 1/13 |

| Hall | - | 0/4 | 0/6 | 0/10 |

| B ultrasonic room | 0/1 | 0/2 | 1/4 | 1/7 |

| Reception room | 1/3 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/5 |

| Corridor | - | 0/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 |

| Total | 28/88 | 6/113 | 17/165 | 51/366 |

| Strains | Origin | Sampling Location and Time | ST-spa Typing | Resistance Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDH9P8A | Cat-3, nasal swab | Veterinary hospital 1, April 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY/SXT |

| GDB9Z6A-1 | Airborne dust, clinic room-4 | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t034 | - |

| GDB9Z8A-1 | Airborne dust, clinic room-6 | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t011 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z15A-1 | Airborne dust, inpatient department-4 | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t034 | - |

| GDB9Z33A-2 | Dog-7, nasal swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z39A-3 | Male veterinarians-4, nasal swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z40A-3 | Male veterinarians-5, nasal swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t034 | PEN/FFC/ERY/CIP |

| GDB9Z42A-3 | Male veterinarians-6, skin swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z43A-3 | Male veterinarians-7, skin swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t034 | PEN/FFC/ERY/CIP |

| GDB9Z44A-2 | Female veterinarians-3, skin swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z45A-3 | Female veterinarians-4, skin swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t034 | PEN/FFC/ERY/CIP |

| GDB9Z55A-1 | Environmental surfaces, cage interior-10 | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z60A-1 | Dog-6, eye swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z63A-2 | Dog-9, eye swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z66A-1 | Dog-12, eye swab | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z72A-2 | Medical device surfaces, surgical forceps-2 | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

| GDB9Z73A-1 | Medical device surfaces, surgical scissors-1 | Veterinary hospital 1, July 2019 | ST398-t571 | PEN/ERY |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Tang, Z.-Y.; Cui, S.-Y.; Ma, Z.-B.; Deng, H.; Kong, W.-L.; Yang, L.-W.; Lin, C.; Xiong, W.-G.; Zeng, Z.-L. Biofilm Production Ability, Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Staphylococcus aureus from Various Veterinary Hospitals. Pathogens 2020, 9, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9040264

Chen L, Tang Z-Y, Cui S-Y, Ma Z-B, Deng H, Kong W-L, Yang L-W, Lin C, Xiong W-G, Zeng Z-L. Biofilm Production Ability, Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Staphylococcus aureus from Various Veterinary Hospitals. Pathogens. 2020; 9(4):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9040264

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lin, Zi-Yun Tang, Shi-Yun Cui, Zhen-Bao Ma, Hua Deng, Wei-Li Kong, Li-Wen Yang, Chao Lin, Wen-Guang Xiong, and Zhen-Ling Zeng. 2020. "Biofilm Production Ability, Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Staphylococcus aureus from Various Veterinary Hospitals" Pathogens 9, no. 4: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9040264

APA StyleChen, L., Tang, Z.-Y., Cui, S.-Y., Ma, Z.-B., Deng, H., Kong, W.-L., Yang, L.-W., Lin, C., Xiong, W.-G., & Zeng, Z.-L. (2020). Biofilm Production Ability, Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Staphylococcus aureus from Various Veterinary Hospitals. Pathogens, 9(4), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9040264