Evolutionary Trajectory for the Emergence of Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Whole Genome-Based Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of Coronavirus

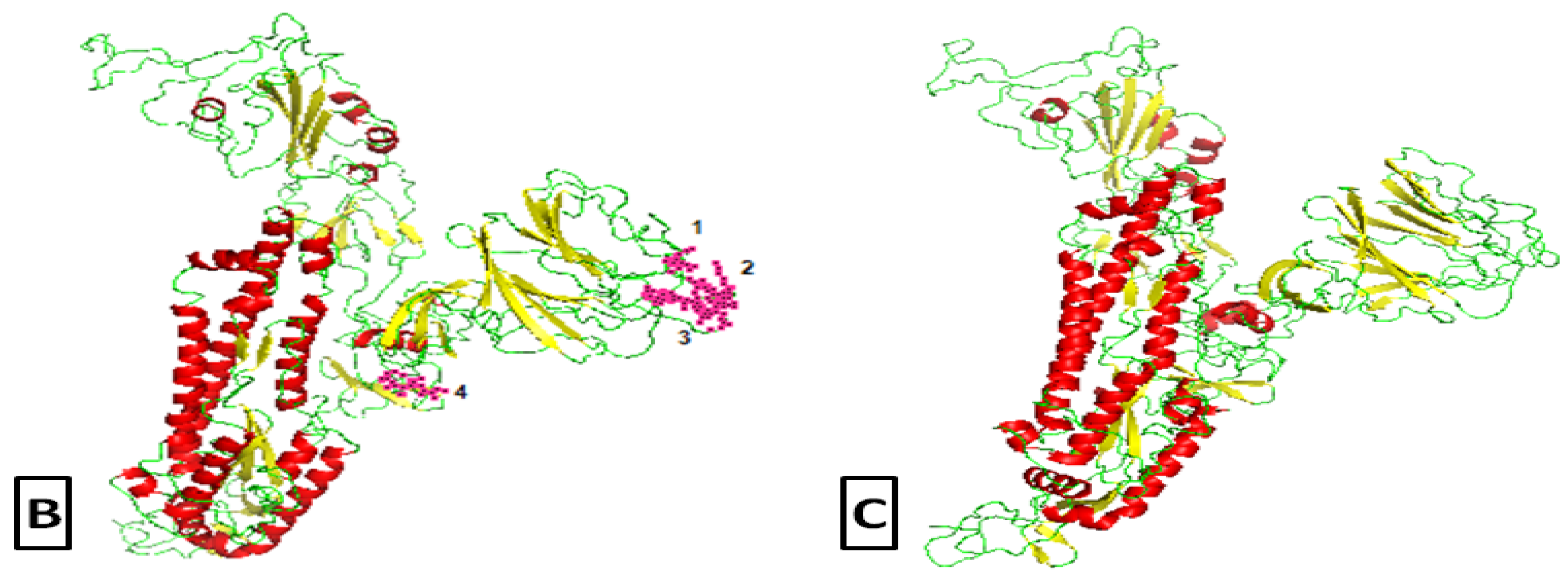

2.2. Comparative Genomics of Wuhan-Hu-1-CoV and SARS CoV

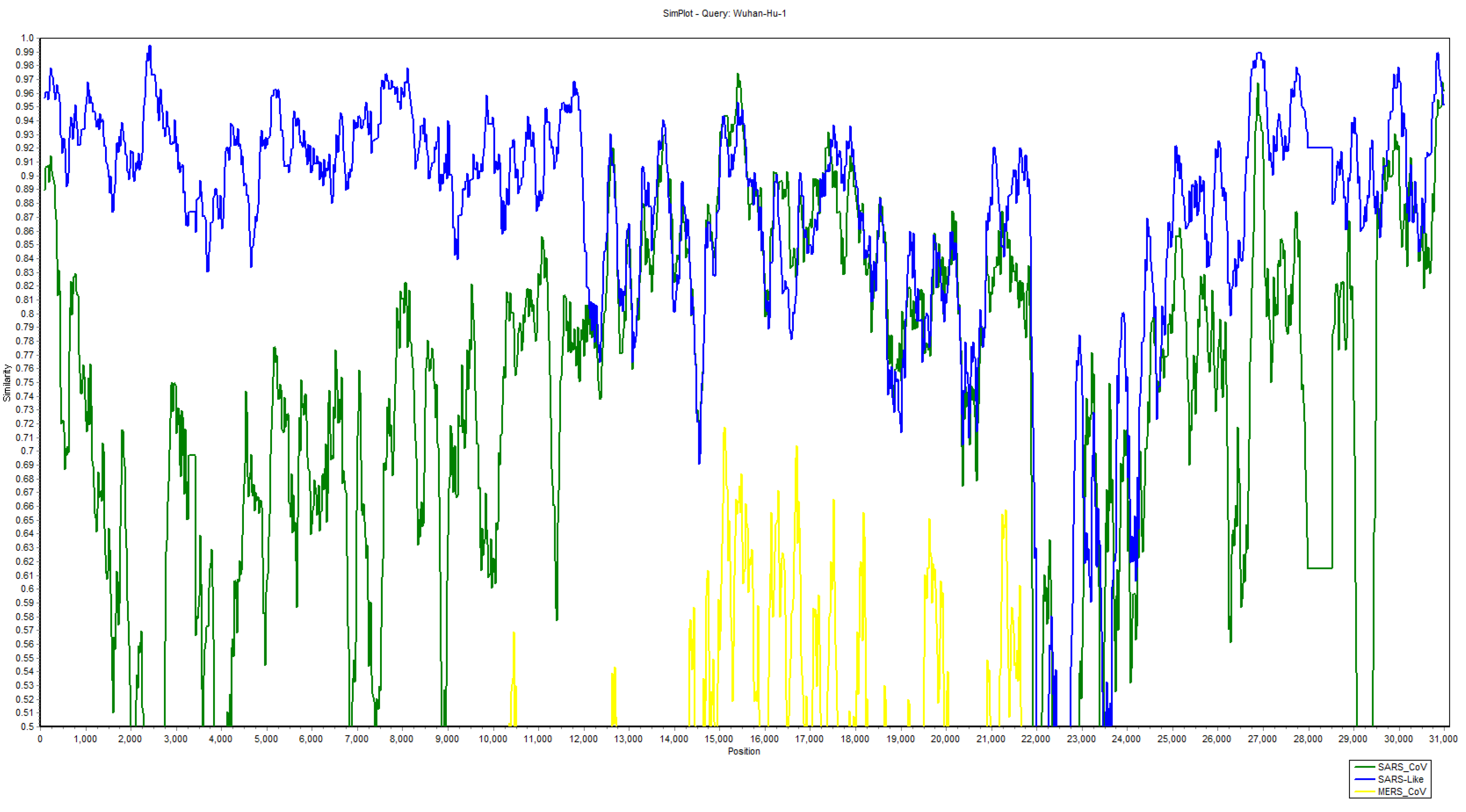

2.3. Recombination Events in Newly Emerged Coronavirus

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, G.F. From “A”IV to “Z”IKV: Attacks from emerging and re-emerging pathogens. Cell 2018, 172, 1157–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Niu, P. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbalenya, E.A.; Baker, S.C.; Baric, R.S.; Groot, R.J.; Drosten, C.; Gulyaeva, A.A.; Haagmans, B.L.; Lauber, C.; Leontovich, A.M.; Neuman, B.W.; et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: The species and its viruses—A statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, P.S.; Perlman, S. Coronaviridae. In Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 825–858. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, S.R.; Leibowitz, J.L. Coronavirus pathogenesis. Adv. Virus Res. 2011, 81, 85–164. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.; Zhou, J.; Gao, G.F. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C.; Li, K.S.; Huang, Y.; Tsoi, H.W.; Wong, B.H.; Wong, S.S.; Leung, S.Y.; Chan, K.H.; Yuen, K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 14040–14045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (MERS-CoV). 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- WHO (Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 Situation). 2020. Available online: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/685d0ace521648f8a5beeeee1b9125cd (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Lai, M.M.C. Recombination in large RNA viruses: Coronaviruses. Semin. Virol. 1996, 7, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, S.G.; Sawicki, D.L. A new model for coronavirus transcription. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998, 440, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Spaan, W.; Delius, H.; Skinner, M.A.; Armstrong, J.; Rottier, P.; Smeekens, S.; Siddell, S.G.; Zeijst, B. Transcription strategy of coronaviruses: Fusion of non-contiguous sequences during mRNA synthesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1984, 173, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Marle, G.; Most, R.G.; Straaten, T.; Luytjes, W.; Spaan, W.J. Regulation of transcription of coronaviruses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1995, 380, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kottier, S.A.; Cavanagh, D.; Britton, P. Experimental evidence of recombination in coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. Virology 1995, 213, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, D.; Davis, P.J. Evolution of avian coronavirus IBV: Sequence of the matrix glycoprotein gene and intergenic region of several serotypes. J. Gen. Virol. 1988, 69, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, D.; Davis, P.J.; Cook, J.K.A. Infectious bronchitis virus: Evidence for recombination within the Massachusetts serotype. Avian Pathol. 1992, 21, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Karaca, K.; Parrish, C.R.; Naqi, S.A. Anovel variant of avian infectious bronchitis virus resulting from recombination among three different strains. Arch. Virol. 1995, 140, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Junker, D.; Collisson, E.W. Evidence of natural recombination within the S1 gene of infectious bronchitis virus. Virology 1993, 192, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Junker, D.; Hock, L.; Ebiary, E.; Collisson, E.W. Evolutionary implications of genetic variations in the S1 gene of infectious bronchitis virus. Virus Res. 1994, 34, 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Collisson, E.W. Experimental confirmation of recombination upstream of the S1 hypervariable region of infectious bronchitis virus. Virus Res. 1997, 49, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markino, S.; Keck, J.G.; Stohlman, S.A.; Lai, M.M.C. High-frequency RNA recombination of murine coronaviruses. J. Virol. 1986, 57, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. MERS, SARS, and Ebola: The role of super-spreaders in infectious disease. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Shi, Z.L.; Zhou, P. Bat Coronaviruses in China. Viruses 2019, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus—Japan (ex-China). Available online: https://www.who.int/csr/don/16-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-japan-ex-china/en/ (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- CDC. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Wuhan, China. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/novel-coronavirus-2019.html (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Hui, E.K.W. Reasons for the increase in emerging and re-emerging viral infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menachery, V.D.; Yount, B.L.; Sims, A.C.; Debbink, K.; Agnihothram, S.S.; Gralinski, L.E.; Swanstrom, J. SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 3048–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menachery, V.D.; Yount, B.L., Jr.; Debbink, K.; Agnihothram, S.; Gralinski, L.E.; Plante, J.A.; Graham, R.L.; Scobey, T.; Ge, X.Y.; Donaldson, E.F.; et al. A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1508–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. Preliminary Phylogenetic Analysis of 11 nCoV2019 Genomes, 2020-01-19. 2020. Available online: http://virological.org/t/preliminary-phylogenetic-analysis-of-11-ncov2019-genomes-2020-01-19/329 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Bedford, T.; Neher, R. Genomic Epidemiology of Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Using Data Generated by Fudan University, China CDC, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Thai National Institute of Health Shared via GISAID. 2020. Available online: https://nextstrain.org/ncov (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Menachery, V.D.; Graham, R.L.; Baric, R.S. Jumping species-a mechanism for coronavirus persistence and survival. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.M.; Graham, R.L.; Donaldson, E.F.; Rockx, B.; Sims, A.C.; Sheahan, T.; Pickles, R.J.; Corti, D.; Johnston, R.E.; Baric, R.S. Synthetic recombinant bat SARS-like coronavirus is infectious in cultured cells and in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 19944–19949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.T.; Whitfield, Z.J.; Andino, R. Mapping the evolutionary potential of RNA viruses. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nao, N.; Yamagishi, J.; Miyamoto, H.; Igarashi, M.; Manzoor, R.; Ohnuma, A.; Kishida, N. Genetic predisposition to acquire a polybasic cleavage site for highly pathogenic avian influenza virus hemagglutinin. MBio 2017, 8, e02298-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.M.; Woo, P.C.; Lau, S.K.; Tse, H.; Chen, H.L.; Li, F.; Yuen, K.Y. Spike protein, S, of human coronavirus HKU1: Role in viral life cycle and application in antibody detection. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 233, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follis, K.E.; York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Furin cleavage of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein enhances cell–cell fusion but does not affect virion entry. Virology 2008, 350, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menachery, V.D.; Dinnon, K.H.; Yount, B.L.; McAnarney, E.T.; Gralinski, L.E.; Hale, A.; Graham, B. Trypsin Treatment Unlocks Barrier for Zoonotic Bat Coronavirus Infection. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.J.; Brown, I.H. History of highly pathogenic avian influenza. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2009, 28, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Xing-Lou, Y.; Xian-Guang, W. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo, E.; Biebrichen, C.K.; Eigen, M.; Holland, J.J. Quasispecies and RNA Virus Evolution: Principles and Consequences; Landes Bioscience: Georgetown, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, T.C.S. Molecular evolution of the SARS coronavirus during the course of the SARS epidemic in China. Science 2004, 303, 1666–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Zhong, W.; Hao, P. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Pandey, A.K.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, P.; Tripathi, P.K.; Menon, M.B.; Kundu, B. Uncanny similarity of unique inserts in the 2019-nCoV spike protein to HIV-1 gp120 and Gag. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worobey, M.; Holmes, E.C. Evolutionary aspects of recombination in RNA viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1999, 80, 2535–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.M.C. RNA recombination in animal and plant viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 56, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.M.C.; Cavanagh, D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1997, 48, 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Jackwood, M.W.; Boynton, T.O.; Hilt, D.A.; McKinley, E.T.; Kissinger, J.C.; Paterson, A.H.; Robertson, J.; Lemke, C.; McCall, A.W.; Williams, S.M.; et al. Emergence of a group 3 coronavirus through recombination. Virology 2010, 398, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, D. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: Empirical data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002, 19, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrinides, J.; Guttman, D.S. Mosaic evolution of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.W.; Yap, Y.L.; Danchin, A. Testing the hypothesis of a recombinant origin of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Arch. Virol. 2004, 150, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazutaka, K.; John, R.; Kazunori, D.Y. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree v1.4.4. Institute of Evolutionary Biology; University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Corpet, F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, L.A.; Mezulis, S.; Yates, C.M.; Wass, M.N.; Sternberg, M.J. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.1; Schrodinger LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Williamson, C.; Posada, D. RDP2: Recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lole, K.S.; Bollinger, R.C.; Paranjape, R.S.; Gadkari, D.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Novak, N.G.; Ingersoll, R.; Sheppard, H.W.; Ray, S.C. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Envelop Protein | Membrane Protein | Nucleocapsid Protein | Spike Protein | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homology | Genetic Variations | Homology | Genetic Variations | Homology | Genetic Variations | Homology | Genetic Variations |

| 93% | 07% | 92% | 08% | 93% | 07% | 81% | 19% |

| Sr.No. | Region | Position of Break and Endpoint | Parents | Methods and p-Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begin | End | Major | Minor | RDP | Bootscan | MaxChi | Chimaera | 3Seq | ||

| 1 | RdRp | 15504 | 16692 | ZXC21 | Rf1 | 3.1 × 10−25 | 2.9 × 10−26 | 2.8 × 10−12 | 3.2 × 10−15 | 8.7 × 10−04 |

| 2 | Helicase | 16693 | 17932 | ZC45 | W1V1 | 4.4 × 10−13 | 1.6 × 10−12 | 2.3 × 10−02 | 7.2 × 10−11 | - |

| 3 | S | 22077 | 22124 | ZC45 | Rf1 | 1.8 × 10−03 | - | - | - | 8.5 × 10−04 |

| 4 | S | 22299 | 22435 | Rf1 | GZ02 | 1.4 × 10−02 | - | - | - | 3.5 × 10−30 |

| 5 | S | 23117 | 23270 | ZXC21 | W1V1 | 1.0 × 10−05 | 3.4 × 10−05 | - | 1.6 × 10−02 | 2.3 × 10−11 |

| 6 | S | 23519 | 23787 | ZXC21 | Rf1 | 4.5 × 10−14 | 6.8 × 10−13 | 4.5 × 10−04 | 6.4 × 10−05 | 6.2 × 10−14 |

| 7 | S | 23897 | 24342 | ZXC21 | Rf1 | 8.5 × 10−16 | 8.8 × 10−12 | - | - | - |

| 8 | S | 24716 | 24790 | ZC45 | GZ02 | 1.8 × 10−05 | 1.4 × 10−04 | - | - | 1.7 × 10−03 |

| 9 | ORF3a | 25745 | 25862 | ZC45 | GZ02 | 3.8 × 10−08 | 4.1 × 10−07 | - | - | 1.5 × 10−04 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rehman, S.u.; Shafique, L.; Ihsan, A.; Liu, Q. Evolutionary Trajectory for the Emergence of Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens 2020, 9, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030240

Rehman Su, Shafique L, Ihsan A, Liu Q. Evolutionary Trajectory for the Emergence of Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens. 2020; 9(3):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030240

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehman, Saif ur, Laiba Shafique, Awais Ihsan, and Qingyou Liu. 2020. "Evolutionary Trajectory for the Emergence of Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2" Pathogens 9, no. 3: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030240

APA StyleRehman, S. u., Shafique, L., Ihsan, A., & Liu, Q. (2020). Evolutionary Trajectory for the Emergence of Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens, 9(3), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030240