Infective Endocarditis by Fusobacterium Species—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

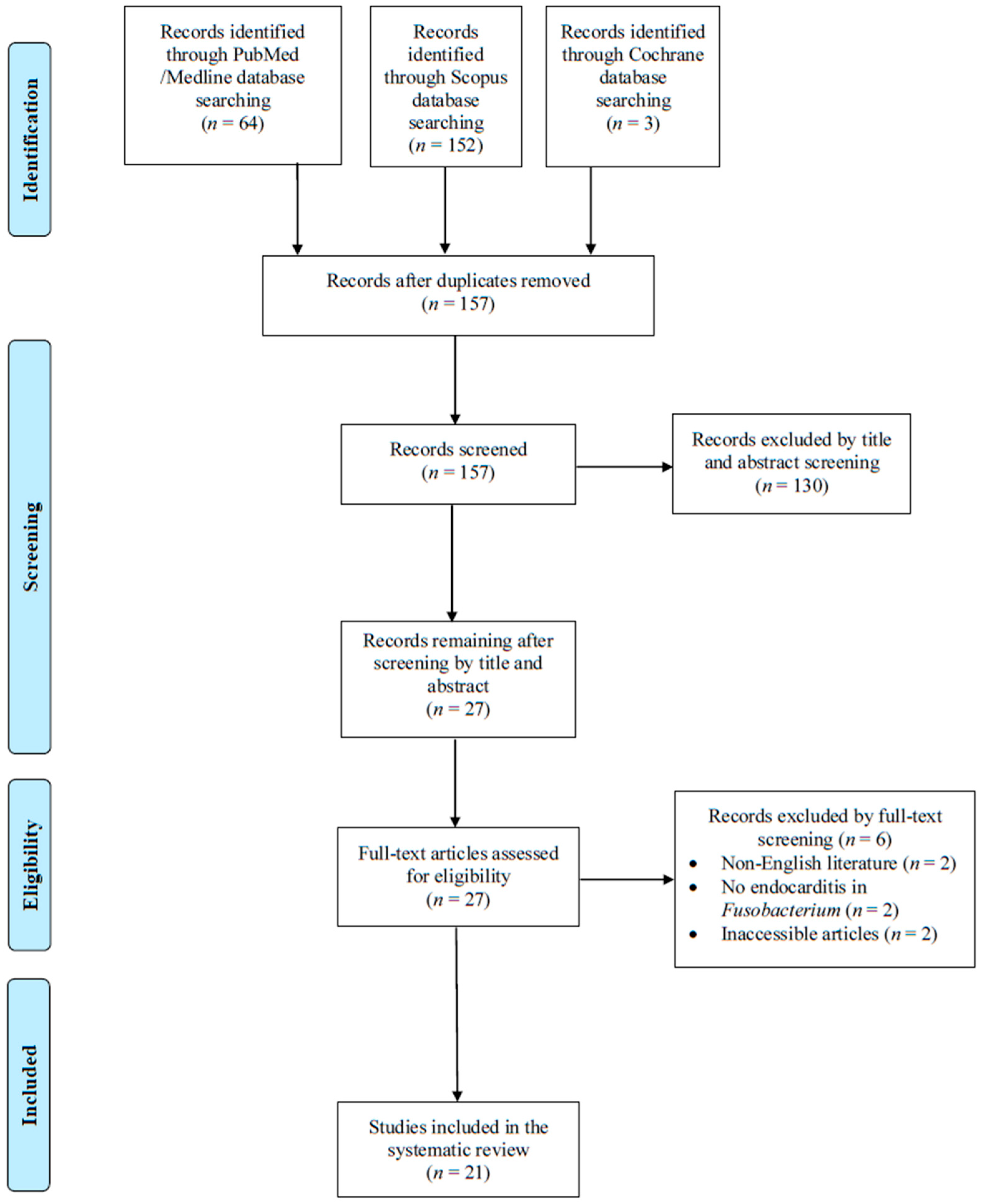

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Search

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Outcomes of Interest

2.4. Data Extraction and Definitions

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Included Studies’ Characteristics

3.3. Fusobacterium spp. IE Characteristics

3.4. Treatment and Outcome of IE by Fusobacterium spp.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bennett, J.E.; Dolin, R.; Blaser, M.J. (Eds.) Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 9th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-323-48255-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rajani, R.; Klein, J.L. Infective Endocarditis: A Contemporary Update. Clin. Med. Lond. Engl. 2020, 20, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; Donal, E.; Cosyns, B.; Laroche, C.; Popescu, B.A.; Prendergast, B.; Tornos, P.; Sadeghpour, A.; et al. Clinical Presentation, Aetiology and Outcome of Infective Endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European Infective Endocarditis) Registry: A Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3222–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.S.V.; McAllister, D.A.; Gallacher, P.; Astengo, F.; Rodríguez Pérez, J.A.; Hall, J.; Lee, K.K.; Bing, R.; Anand, A.; Nathwani, D.; et al. Incidence, Microbiology, and Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized with Infective Endocarditis. Circulation 2020, 141, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, P.E.; Samonis, G.; Andrianaki, A.M.; Christofaki, M.; Dimopoulou, D.; Papadakis, J.; Gikas, A.; Kofteridis, D.P. Epidemiology, Microbiological and Clinical Features, Treatment, and Outcomes of Infective Endocarditis in Crete, Greece. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 50, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapti, V.; Giannitsioti, E.; Spernovasilis, N.; Magiorakos, A.-P.; Poulakou, G. The Evolving Landscape of Infective Endocarditis: Difficult-to-Treat Resistance Bacteria and Novel Diagnostics at the Foreground. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresti, A.; Chiavarelli, M.; Scalese, M.; Nencioni, C.; Valentini, S.; Guerrini, F.; D’Aiello, I.; Picchi, A.; De Sensi, F.; Habib, G. Epidemiological and Mortality Trends in Infective Endocarditis, a 17-Year Population-Based Prospective Study. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2017, 7, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.R.; Jenks, J.D.; Baddley, J.W.; Lewis, J.S.; Egger, M.; Schwartz, I.S.; Boyer, J.; Patterson, T.F.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Pappas, P.G.; et al. Fungal Endocarditis: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 36, e0001923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestler, M.; Muñoz, P.; Marín, M.; Goenaga, M.A.; Idígoras Viedma, P.; de Alarcón, A.; Lepe, J.A.; Sousa Regueiro, D.; Bravo-Ferrer, J.M.; Pajarón, M.; et al. Endocarditis Caused by Anaerobic Bacteria. Anaerobe 2017, 47, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nord, C.E. Anaerobic Bacteria in Septicaemia and Endocarditis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 1982, 31, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, C.A.; Garrett, W.S. Fusobacterium nucleatum—Symbiont, Opportunist and Oncobacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Alzghoul, H.; Khan, A.A.; Allada, G.; Gronquist, J.M.; Pak, J.; Mukundan, S.; Zakhary, B.; Wusirika, R.; Sher, N.; et al. Epidemiology and Clinical Outcomes of Fusobacterium Infections: A Six-Year Retrospective Study. Med. Kaunas Lith. 2024, 60, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B. Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: A Proposal for Reporting. Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group. JAMA 2000, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, P.; Kourtidis, M.; Mytilinis, D.-O.; Psyllaki, A.; Baliou, S.; Kofteridis, D. Whipple’s Disease-Associated Infective Endocarditis: A Systematic Review. Infect. Dis. Lond. Engl. 2023, 55, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, V.G.; Durack, D.T.; Selton-Suty, C.; Athan, E.; Bayer, A.S.; Chamis, A.L.; Dahl, A.; DiBernardo, L.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Duval, X.; et al. The 2023 Duke-ISCVID Criteria for Infective Endocarditis: Updating the Modified Duke Criteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2023, 77, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://Jbi.Global/Critical-Appraisal-Tools (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Seggie, J. Fusobacterium Endocarditis Treated with Metronidazole. BMJ 1978, 1, 960–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Levine, D.; Hadley, W.K.; Mills, J. Sextuplibacterial Endocarditis: A New World’s Record? South. Med. J. 1988, 81, 1592–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.G.; Blumberg, E.A.; Schwartz, D.A.; Russin, S.J.; Pepe, R. Seven-Pathogen Tricuspid Endocarditis in an Intravenous Drug Abuser. Chest 1991, 99, 490–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, G.; Wren, C. Endocarditis with Acute Mitral Regurgitation Caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum. Pediatr. Cardiol. 1992, 13, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shammas, N.W.; Murphy, G.W.; Eichelberger, J.; Klee, D.; Schwartz, R.; Bachman, W. Infective Endocarditis Due to Fusobacterium nucleatum: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin. Cardiol. 1993, 16, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, G.; Borer, A.; Riesenberg, K.; Schlaeffer, F. Infective Endocarditis Due to Fusobacterium nucleatum in an Intravenous Drug Abuser. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999, 18, 655–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolamali, S.I.; Carulli, M.T.; Davies, U.M. Spinal Abscess and Mitral Valve Endocarditis Secondary to Asymptomatic Fusobacterium-Induced Dental Abscess. J. R. Soc. Med. 2006, 99, 368–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vedire, S.; Alpert, M.A.; Ren, J.; Manian, F.A. Fusobacterium necrophorum Endocarditis in a Previously Healthy Young Adult. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2007, 334, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Socio, G.V.L.; Mencacci, A.; Bini, P.; Pasticci, M.B. Fusobacterium nucleatum Endocarditis Mimicking Polymyalgia Rheumatica. South. Med. J. 2009, 102, 1082–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augusto, J.-F.; Mercat, A.; Asfar, P.; Pinaud, F.; Croue, A.; Chausseret, L. Fatal Case of Fusobacterium necrophorum Mitral Endocarditis. J. Infect. 2010, 61, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handler, M.Z.; Miriovsky, B.; Gendelman, H.E.; Sandkovsky, U. Fusobacterium necrophorum Causing Infective Endocarditis and Liver and Splenic Abscesses. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2011, 53, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samant, J.S.; Peacock, J.E. Fusobacterium necrophorum Endocarditis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 69, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, C.; Addison, D.; Wilson, J.M.; Zeluff, B. First Case of Fusobacterium necrophorum Endocarditis to Have Presented after the 2nd Decade of Life. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2013, 40, 449–452. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, J.C.; Ford, B.A.; Streit, J.A. Myocardial Infection Due to Fusobacterium nucleatum. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 77, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahya, V.; Patel, J.; Wheeler, M.; Ketsela, G. Fusobacterium nucleatum Endocarditis Presenting as Liver and Brain Abscesses in an Immunocompetent Patient. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 349, 284–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, N.; Connolly, S.; Cheema, B.; Angarone, M. A Curious Case of Endocarditis and Liver Abscess in a Previously Healthy Man. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Matsubara, T.; Imai, S.; Hatada, K.; Mitsuma, W.; Kawasaki, S.; Hama, I.; Kamura, T. Fusobacterium necrophorum Endocarditis with Liver Abscesses: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Intern. Med. 2021, 60, 2445–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgut, O.; Mitchell, A.R.J.; Le Page, P. Fusobacterium Species Cardiac Device Infective Endocarditis Diagnosed via Molecular Methods. Clin. Infect. Pract. 2022, 15, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.; Bhargava, R.; Movahed, M.R. Fusobacterium nucleatum Endocarditis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 13, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman, Z.I.; Sharma, D.; Rivera Salva, J.; Rast, J.; Samra, H.; Askar, G. A Rare Case of Cerebral Abscess Due to Fusobacterium nucleatum with Native Aortic Valve Infective Endocarditis and Pyogenic Liver Abscess. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2024, 12, 23247096241272014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Robinson, C.; Upadhyaya, P.; Chandra, A.; Prokesch, B.C.; Kang, M. Fusobacterium necrophorum Endocarditis with Intracranial Abscesses: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Cardiol. Cases 2024, 30, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M.G.B.; de Almeida, T.V.d.P.A.; Feijóo, N.d.A.P.; Garrido, R.Q.; Barbosa, G.L.F.; Golebiovski, W.F.; Zappa, B.; Weksler, C.; Correia, M.G.; da Cruz Lamas, C. Contemporary Cohort Study in Adult Patients with Infective Endocarditis. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Braz. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2025, 29, 104521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.T.; O’Rourke, S.; Buckley, A.; Murphy, R.; Crean, P.; Foley, B.; Maree, A.; Ryan, R.; Tolan, M.; Young, V.; et al. Infective Endocarditis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. QJM Mon. J. Assoc. Physicians 2019, 112, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, D.R.; Corey, G.R.; Hoen, B.; Miró, J.M.; Fowler, V.G.; Bayer, A.S.; Karchmer, A.W.; Olaison, L.; Pappas, P.A.; Moreillon, P.; et al. Clinical Presentation, Etiology, and Outcome of Infective Endocarditis in the 21st Century: The International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slots, J. Periodontitis: Facts, Fallacies and the Future. Periodontol. 2000 2017, 75, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, P.; Kopidakis, I.; Makraki, E.; Baliou, S.; Samonis, G. Infective Endocarditis by Clostridioides and Clostridium Species—A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Siciliano, R.F.; Zeigler, R.; Strabelli, T.M.V. Bacteroides Fragilis Endocarditis: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Braz. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, 100–104. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Banzon, J.M.; Rehm, S.J.; Gordon, S.M.; Hussain, S.T.; Pettersson, G.B.; Shrestha, N.K. Propionibacterium Acnes Endocarditis: A Case Series. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.D.; Vranckx, K.; Copsey-Mawer, S.; Scotford, S.; Anderson, B.; Day, P.; Watkins, J.; Corden, S.; Hughes, H.; Morris, T.E. First Large-Scale Study of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Data, and Genetic Resistance Determinants, in Fusobacterium necrophorum Highlighting the Importance of Continuing Focused Susceptibility Trend Surveillance. Anaerobe 2023, 80, 102717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Huang, Y.-T.; Liao, C.-H.; Yen, L.-C.; Lin, H.-Y.; Hsueh, P.-R. Increasing Trends in Antimicrobial Resistance among Clinically Important Anaerobes and Bacteroides Fragilis Isolates Causing Nosocomial Infections: Emerging Resistance to Carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3161–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Bayer, A.S. Combination Antibiotic Therapy for Infective Endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2003, 36, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Beganovic, M.; Luther, M.K.; Rice, L.B.; Arias, C.A.; Rybak, M.J.; LaPlante, K.L. A Review of Combination Antimicrobial Therapy for Enterococcus Faecalis Bloodstream Infections and Infective Endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.; McDermott, H.; Gash, S.; O’Connor, C.; O’Connell, K.; O’Donnell, S.; Dinesh, B.; Burns, K.; Fitzpatrick, F. Getting to the Heart of the Matter—Are Two Agents Really Better than One for the Treatment of Staphylococcal Infective Endocarditis? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 142, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | All Patients (n = 21) * | Fusobacterium necrophorum ** (n = 10) * | Fusobacterium nucleatum (n = 9) * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 48 (25–57.5) | 25 (19.8–41.5) | 53 (48–71.5) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 18 (85.7) | 8 (80) | 9 (100) |

| Predisposing factors | |||

| Bad teeth hygiene or recent dental work, n (%) | 10 (47.6) | 2 (20) | 7 (77.8) |

| IVDU, n (%) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (10) | 2 (22.2) |

| CIED, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (22.2) |

| Prosthetic valve, n (%) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Congenital heart disease, n (%) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Rheumatic fever, n (%) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Post cardiac surgery, n (%) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Method of diagnosis | |||

| Transthoracic echocardiography, n (%) | 3/17 (17.6) | 2/9 (22.2) | 1/7 (14.3) |

| Transesophageal echocardiography, n (%) | 13/16 (81.3) | 7/9 (77.8) | 5/6 (83.3) |

| Valve localization | |||

| Mitral valve, n (%) | 8/18 (44.4) | 5 (50) | 3/7 (42.9) |

| Aortic valve, n (%) | 5/18 (27.8) | 3 (30) | 2/7 (28.6) |

| Tricuspid valve, n (%) | 3/18 (16.7) | 2 (20) | 1/7 (14.3) |

| Right ventricle mass, n (%) | 1/18 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 1/7 (14.3) |

| CIED, n (%) | 1/18 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 0/7 (0) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Fever, n (%) | 21 (100) | 10 (100) | 9 (100) |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 19 (90.5) | 10 (100) | 8 (88.9) |

| Embolic phenomena, n (%) | 17 (81) | 7 (70) | 8 (88.9) |

| Immunological phenomena, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 2 (20) | 2 (22.2) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Shock, n (%) | 3/20 (15) | 2 (20) | 1 (11.1) |

| Paravalvular abscess, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Treatment | |||

| Metronidazole, n (%) | 13 (61.9) | 4 (40) | 7 (77.8) |

| Aminopenicillin, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 2 (20) | 2 (22.2) |

| Penicillin, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (30) | 2 (22.2) |

| Cephalosporin, n (%) | 4 (19) | 3 (30) | 1 (11.1) |

| Carbapenem, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (10) | 1 (11.1) |

| Antipseudomonal penicillin, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Clindamycin, n (%) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Surgical management, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Duration of treatment, weeks, median (IQR) | 6 (6–9.8) | 6 (6–9) | 8.5 (4.5–13) |

| Outcomes | |||

| Deaths due to infection, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Deaths overall, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ioannou, P.; Mourati, E.; Thalasseli Kazali, S.; Bali, C.; Baliou, S.; Samonis, G. Infective Endocarditis by Fusobacterium Species—A Systematic Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080829

Ioannou P, Mourati E, Thalasseli Kazali S, Bali C, Baliou S, Samonis G. Infective Endocarditis by Fusobacterium Species—A Systematic Review. Pathogens. 2025; 14(8):829. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080829

Chicago/Turabian StyleIoannou, Petros, Eleni Mourati, Styliani Thalasseli Kazali, Chrysoula Bali, Stella Baliou, and George Samonis. 2025. "Infective Endocarditis by Fusobacterium Species—A Systematic Review" Pathogens 14, no. 8: 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080829

APA StyleIoannou, P., Mourati, E., Thalasseli Kazali, S., Bali, C., Baliou, S., & Samonis, G. (2025). Infective Endocarditis by Fusobacterium Species—A Systematic Review. Pathogens, 14(8), 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080829