Pentraxin 3 Levels Reflect Inflammatory and Parasitic Activity in Human Visceral Leishmaniasis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Sample Collection and Processing

2.5. Parasite Load Quantification

2.6. Determination of PTX3 Concentration

2.7. PTX3 Genotyping

2.8. Cytokine Quantification

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics

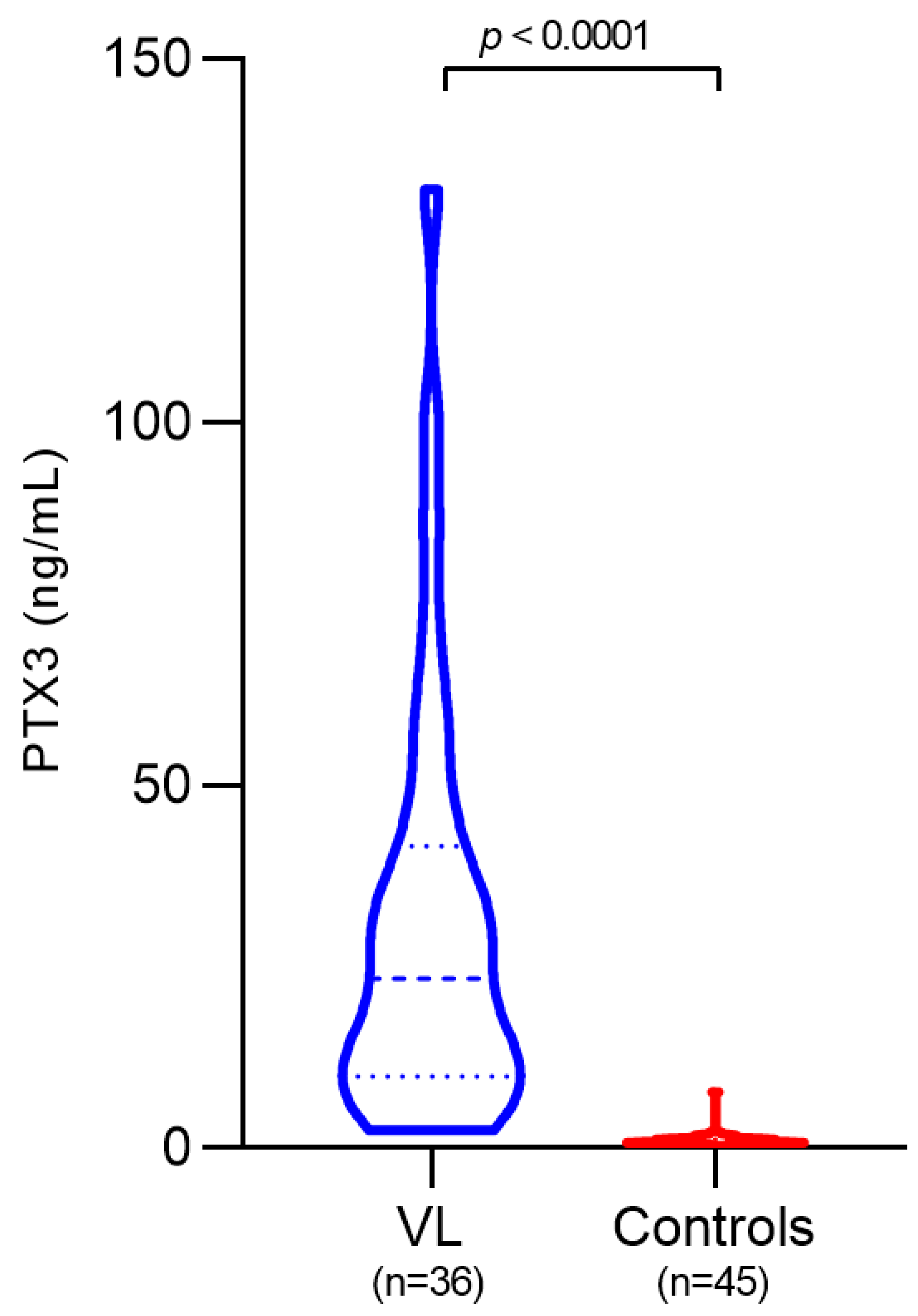

3.2. Plasma PTX3 Levels in VL Patients and Controls

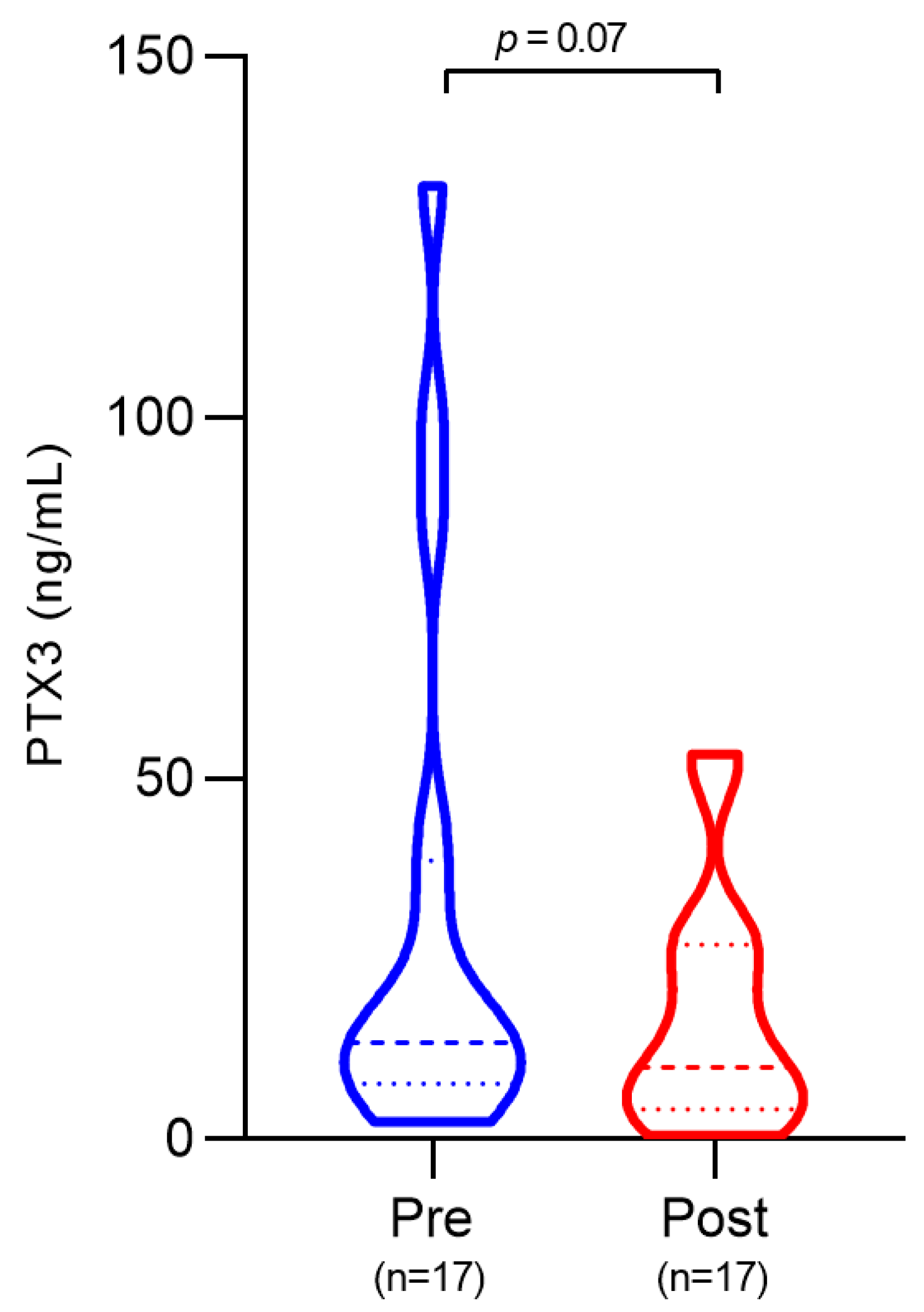

3.3. Plasma PTX3 Levels Before and After Treatment

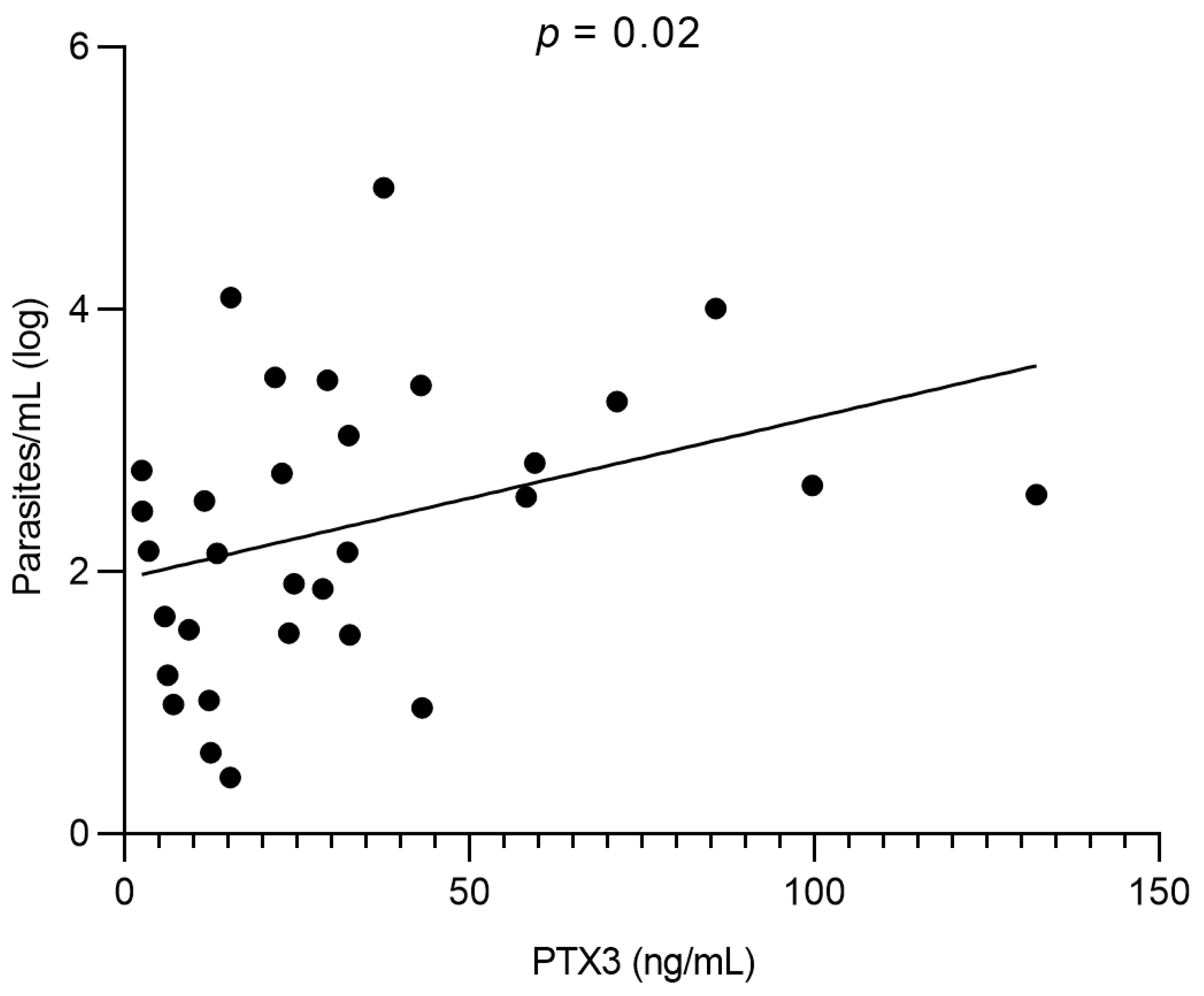

3.4. Correlation Between PTX3 and Parasite Load

3.5. PTX3 Gene Polymorphisms

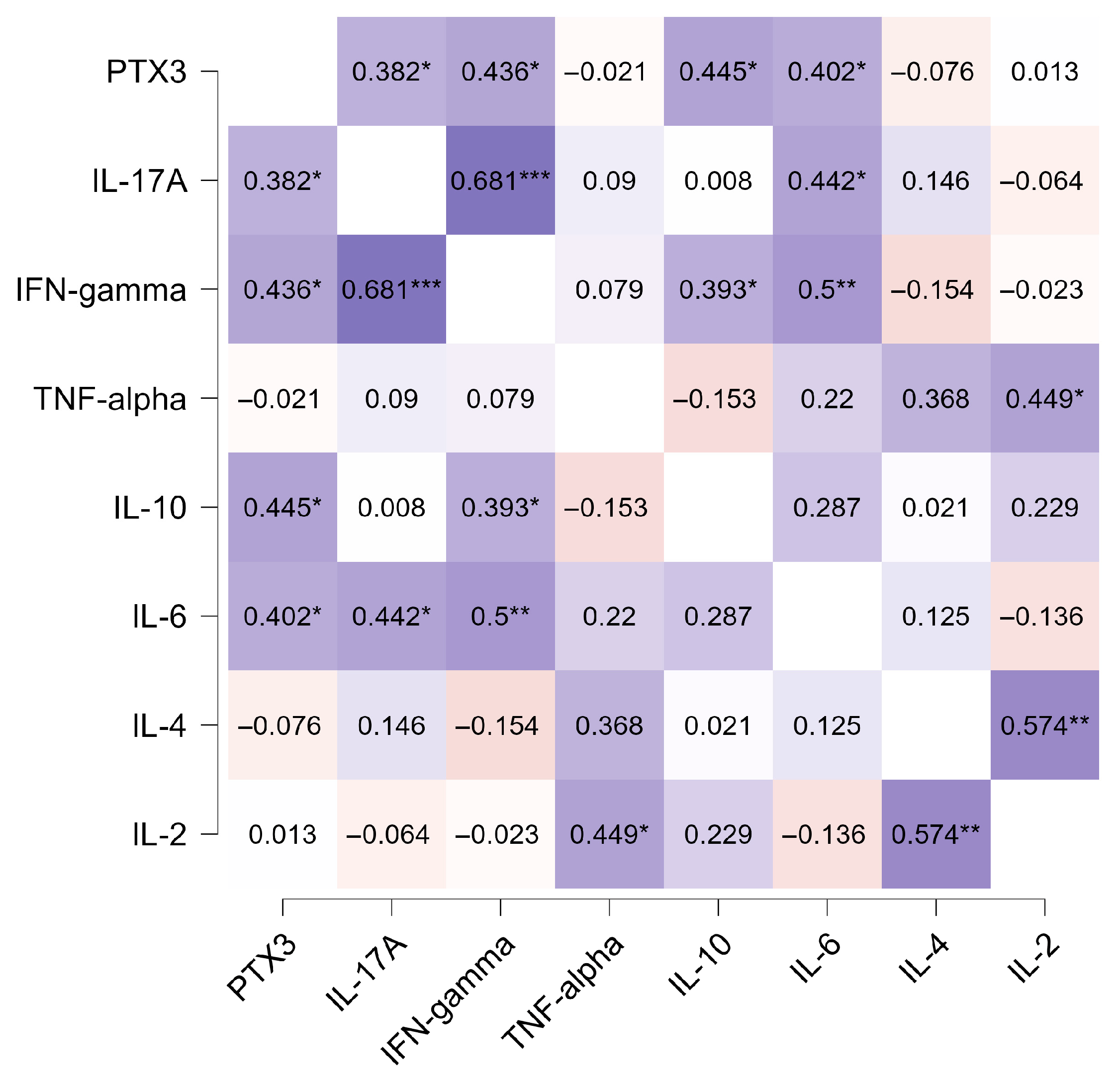

3.6. Correlation Between PTX3 and Inflammatory Cytokines

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis: Fact Sheet; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Bruhn, F.R.P.; Werneck, G.L.; Barbosa, D.S.; Câmara, D.C.P.; Simões, T.C.; Buzanovsky, L.P.; Duarte, A.G.S.; de Melo, S.N.; Cardoso, D.T.; Donato, L.E.; et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil: A nonlinear regression analysis. Zoonoses Public Health 2024, 71, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, L.F.B.; de Souza, C.D.F.; Carmo, R.F.D. Epidemiology of human visceral leishmaniasis in the urban centers of the lower-middle São Francisco Valley, Brazilian semiarid region. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2018, 51, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.W.F.; Souza, C.D.F.; Carmo, R.F. Temporal and spatial trends in human visceral leishmaniasis in an endemic area in Northeast Brazil and their association with social vulnerability. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas-Torres, F.; da Silva Sales, K.G.; Gomes da Silva, L.; Otranto, D.; Figueredo, L.A. Leishmania-FAST15: A rapid, sensitive and low-cost real-time PCR assay for the detection of Leishmania infantum and Leishmania braziliensis kinetoplast DNA in canine blood samples. Mol. Cell Probes. 2017, 31, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, S.R.; Diniz, L.F.B.; Nunes, S.L.P.; Silva, R.L.O.; Gouveia, G.V.; Gouveia, J.J.S.; Sales, K.G.D.S.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Carmo, R.F.D.; Gouveia, J.J.S. Blood parasite load by qPCR as therapeutic monitoring in visceral leishmaniasis patients in Brazil: A case series study. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2023, 56, e0456-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrest, L.; E Kip, A.; Musa, A.M.; Schoone, G.J.; Schallig, H.D.F.H.; Mbui, J.; Khalil, E.A.G.; Younis, B.M.; Olobo, J.; Were, L.; et al. Blood Parasite Load as an Early Marker to Predict Treatment Response in Visceral Leishmaniasis in Eastern Africa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulik, S.; Sengupta, S.; Chatterjee, M. Molecular Tracking of the Leishmania Parasite. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 623437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadesse, D.; Abdissa, A.; Mekonnen, M.; Belay, T.; Hailu, A. Antibody and cytokine levels in visceral leishmaniasis patients with varied parasitemia before, during, and after treatment in patients admitted to Arba Minch General Hospital, southern Ethiopia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo-Santos, T.; Andrade, B.B.; Gil-Santana, L.; Luz, N.F.; dos Santos, P.L.; de Oliveira, F.A.; Almeida, M.L.; Campos, R.N.d.S.; Bozza, P.T.; Almeida, R.P.; et al. Anti-parasite therapy drives changes in human visceral leishmaniasis-associated inflammatory balance. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.S.; Braz, D.C.; Silva, V.C.; Farias, T.J.C.; Zacarias, D.A.; da Silva, J.C.; Costa, C.H.N.; Costa, D.L. Biomarkers of the early response to treatment of visceral leishmaniasis: A prospective cohort study. Parasite Immunol. 2021, 43, e12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillon, S.; Bonavita, E.; Gentile, S.; Rubino, M.; Laface, I.; Garlanda, C.; Mantovani, A. The long pentraxin PTX3 as a key component of humoral innate immunity and a candidate diagnostic for inflammatory diseases. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 165, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.; Luo, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Molecular insight into pentraxin-3: Updated advances in innate immunity, inflammation, tissue remodeling, diseases, and drug role. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alles, V.V.; Bottazzi, B.; Peri, G.; Golay, J.; Introna, M.; Mantovani, A. Inducible expression of PTX3, a new member of the pentraxin family, in human mononuclear phagocytes. Blood 1994, 84, 3483–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, A.C.C.G.; da Luz, R.C.F.V.; Fernandes, A.L.M.; Barbosa, M.X.S.; de Andrade, L.V.; Armstrong, A.d.C.; de Souza, C.D.F.; Carmo, R.F.D. Association of PTX3 gene polymorphisms and PTX3 plasma levels with leprosy susceptibility. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Li, H.; Rui, Y.; Liu, L.; He, B.; Shi, Y.; Su, X. Pentraxin 3 Gene Polymorphisms and Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, T.A.; Sá, M.V.d.S.; Pereira, V.C.; Cavalcante, M.K.d.A.; Pereira, V.R.A.; Armstrong, A.d.C.; Carmo, R.F.D. Association of polymorphisms in long pentraxin 3 and its plasma levels with COVID-19 severity. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbati, E.; Specchia, C.; Villella, M.; Rossi, M.L.; Barlera, S.; Bottazzi, B.; Crociati, L.; D’arienzo, C.; Fanelli, R.; Garlanda, C.; et al. Influence of Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) Genetic Variants on Myocardial Infarction Risk and PTX3 Plasma Levels. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e53030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Mou, Z.; Jia, P.; Sharma, R.; Zayats, R.; Viana, S.M.; Shan, L.; Barral, A.; Boaventura, V.S.; Murooka, T.T.; et al. The Long Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) Suppresses Immunity to Cutaneous Leishmaniasis by Regulating CD4+ T Helper Cell Response. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porte, R.; Davoudian, S.; Asgari, F.; Parente, R.; Mantovani, A.; Garlanda, C.; Bottazzi, B. The long pentraxin PTX3 as a humoral innate immunity functional player and biomarker of infections and sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, B.; Garlanda, C.; Salvatori, G.; Jeannin, P.; Mantovani, A. The pentraxins PTX3 and SAP in innate immunity, regulation of inflammation and tissue remodelling. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1416–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil; Ministério da Saúde; Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Manual de Vigilância e Controle da Leishmaniose Visceral; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Azzurri, A.; Sow, O.Y.; Amedei, A.; Bah, B.; Diallo, S.; Peri, G.; Benagiano, M.; D’eLios, M.M.; Mantovani, A.; Del Prete, G. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 and pentraxin 3 plasma levels are tools for monitoring inflammation and disease activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Microbes Infect. 2005, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-J.; Yang, H.-W.; Tsao, S.-M.; Cheng, C.-W.; Bien, M.-Y.; Yu, M.-C.; Bai, K.-J.; Yang, S.-F.; Chien, M.-H. Plasma long pentraxin 3 (PTX3) concentration is a novel marker of disease activity in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013, 51, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancarella, V.; Lembo-Fazio, L.; Paciello, I.; Bruno, A.-K.; Jaillon, S.; Berardi, S.; Barbagallo, M.; Meron-Sudai, S.; Cohen, D.; Molinaro, A.; et al. Role of a fluid-phase PRR in fighting an intracellular pathogen: PTX3 in Shigella infection. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, J.F.; Goris, M.G.; Gasem, M.H.; Isbandrio, B.; Moalli, F.; Mantovani, A.; Boer, K.R.; Hartskeerl, R.A.; Garlanda, C.; van Gorp, E.C. Long pentraxin PTX3 is associated with mortality and disease severity in severe Leptospirosis. J. Infect. 2009, 58, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprong, T.; Peri, G.; Neeleman, C.; Mantovani, A.; Signorini, S.; van der Meer, J.W.; van Deuren, M. Pentraxin 3 and C-reactive protein in severe meningococcal disease. Shock 2009, 31, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairuhu, A.T.; Peri, G.; Setiati, T.E.; Hack, C.E.; Koraka, P.; Soemantri, A.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Brandjes, D.P.; van der Meer, J.W.; Mantovani, A.; et al. Elevated plasma levels of the long pentraxin, pentraxin 3, in severe dengue virus infections. J. Med. Virol. 2005, 76, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, E.; Col, M.; Migliavacca, M.; Dell’ORo, M.; Silvestri, D.; Montanelli, A.; Peri, G.; Mantovani, A.; Biondi, A.; Rossi, M.R. PTX3 as a potential novel tool for the diagnosis and monitoring of pulmonary fungal infections in immuno-compromised pediatric patients. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2008, 30, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahar, R.; Albergaria, C.; Zeghdour, N.; Ngane, V.F.; Basco, L.K.; Roussilhon, C. Plasma levels of eight different mediators and their potential as biomarkers of various clinical malaria conditions in African children. Malar. J. 2016, 15, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornyigah, B.; Blankson, S.O.; Adamou, R.; Moussiliou, A.; Rietmeyer, L.; Tettey, P.; Dikroh, L.; Addo, B.; Lamptey, H.; Alao, M.J.; et al. Specific Combinations of Inflammatory, Angiogenesis and Vascular Integrity Biomarkers Are Associated with Clinical Severity, Coma and Mortality in Beninese Children with Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Franca, M.N.F.; Rodrigues, L.S.; Barreto, A.S.; da Cruz, G.S.; Aragão-Santos, J.C.; da Silva, A.M.; de Jesus, A.R.; Palatnik-De-Sousa, C.B.; de Almeida, R.P.; Corrêa, C.B.; et al. CD4+ Th1 and Th17 responses and multifunctional CD8 T lymphocytes associated with cure or disease worsening in human visceral leishmaniasis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1277557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, A.; Favali, C.; Aquino, D.; Vinhas, V.; van Weyenbergh, J.; Brodskyn, C.; Costa, J.; Barral-Netto, M.; Barral, A. Balance of IL-10 and interferon-gamma plasma levels in human visceral leishmaniasis: Implications in the pathogenesis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.S.L.; Carregaro, V.; Lima-Júnior, D.S.; Costa, D.L.; Ryffel, B.; Duthie, M.S.; de Jesus, A.; de Almeida, R.P.; da Silva, J.S. Interleukin 17A acts synergistically with interferon γ to promote protection against Leishmania infantum infection. J. Infec Dis. 2015, 211, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, E.; Mantovani, A.; Garlanda, C. The dual complexity of PTX3 in health and disease: A balancing act? Trends Mol Med. 2016, 22, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.J.; Garred, P. Pentraxins in Complement Activation and Regulation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheneef, A.; Hussein, M.T.; Mohamed, T.; Mahmou, A.A.; Youssef, L.; Alkady, O.A. Pentraxin-3 genetic variants and risk of active pulmonary tuberculosis. Egypt. J. Immunol. 2017, 24, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Tang, T.; Huang, B.; Bu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Dai, Y.; Wei, Z.; Huang, L.; Jiang, S. rs1840680 single nucleotide polymorphism in Pentraxin 3: A potential protective biomarker of severe community-acquired pneumonia. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 3000605211010621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | VL (n = 36) | Controls (n = 45) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age (years) *, mean ± sd | 39.4 ± 17.0 | 33.7 ± 10.7 |

| Male sex *, n (%) | 32 (88.8) | 40 (88.8) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Asthenia, n (%) | 32 (88.8) | 0 |

| Fever, n (%) | 30 (83.3) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 19 (52.7) | 0 |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 10 (27.7) | 0 |

| Kidney disease, n (%) | 4 (11.1) | 0 |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 3 (8.3) | 0 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 1 (2.7) | 0 |

| Death, n (%) | 4 (11.1) | 0 |

| Treatment scheme | ||

| ABL, n (%) | 14 (38.8) | 0 |

| GLU, n (%) | 9 (25.0) | 0 |

| ADC, n (%) | 3 (8.3) | 0 |

| GLU followed by ABL, n (%) | 5 (13.8) | 0 |

| ADC followed by GLU, n (%) | 3 (8.3) | 0 |

| ADC followed by ABL, n (%) | 2 (5.5) | 0 |

| VL (n = 36) | Controls (n = 45) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs1840680 | |||

| GG, n (%) | 12 (33.3) | 19 (42.2) | 0.28 |

| AG, n (%) | 19 (52.8) | 16 (35.6) | |

| AA, n (%) | 5 (13.9) | 10 (22.2) | |

| rs2305619 | |||

| GG, n (%) | 7 (19.4) | 15 (33.3) | 0.34 |

| AG, n (%) | 19 (52.8) | 18 (40.0) | |

| AA, n (%) | 10 (27.8) | 12 (26.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diniz, L.F.B.; Barbosa, M.X.S.; de Aquino, S.R.; da Costa Armstrong, A.; Freire de Souza, C.D.; Carmo, R.F. Pentraxin 3 Levels Reflect Inflammatory and Parasitic Activity in Human Visceral Leishmaniasis. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121299

Diniz LFB, Barbosa MXS, de Aquino SR, da Costa Armstrong A, Freire de Souza CD, Carmo RF. Pentraxin 3 Levels Reflect Inflammatory and Parasitic Activity in Human Visceral Leishmaniasis. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121299

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiniz, Lucyo Flávio Bezerra, Milena Xavier Silva Barbosa, Samuel Ricarte de Aquino, Anderson da Costa Armstrong, Carlos Dornels Freire de Souza, and Rodrigo Feliciano Carmo. 2025. "Pentraxin 3 Levels Reflect Inflammatory and Parasitic Activity in Human Visceral Leishmaniasis" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121299

APA StyleDiniz, L. F. B., Barbosa, M. X. S., de Aquino, S. R., da Costa Armstrong, A., Freire de Souza, C. D., & Carmo, R. F. (2025). Pentraxin 3 Levels Reflect Inflammatory and Parasitic Activity in Human Visceral Leishmaniasis. Pathogens, 14(12), 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121299