Immune Responses and Protective Efficacy of Nanoemulsion-Adjuvanted Monkeypox Virus Recombinant Vaccines Against Lethal Challenge in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmids, Cells, and Viruses

2.2. Protein Expression and Purification

2.3. Ethics Statement and Biosafety Compliance

2.4. Nanoemulsion Adjuvant Preparation

2.5. Mouse Immunization and Challenge

2.6. Serum Antibody Analysis by ELISA

2.7. Neutralizing Antibody Measurement

2.8. Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSpot (ELISpot) Assay

2.9. Viral Load Detection by Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

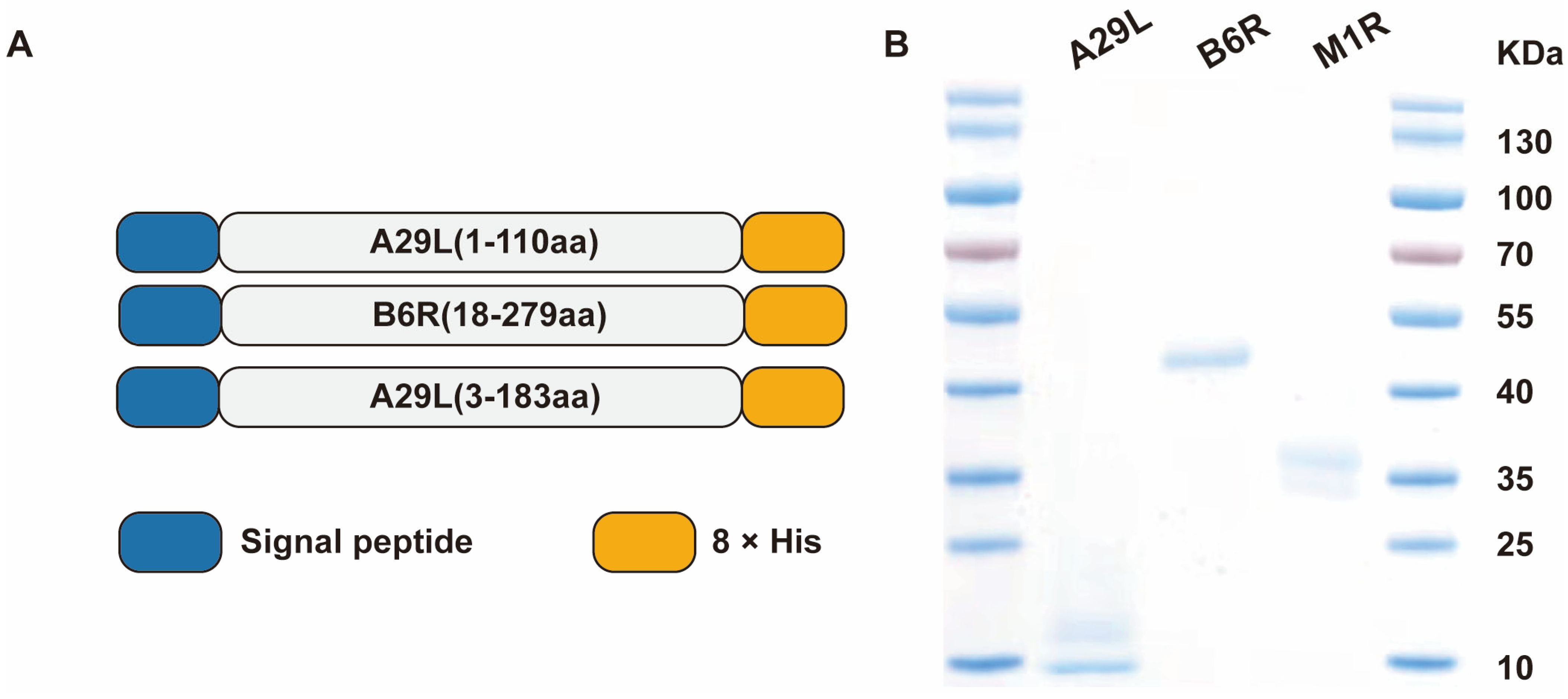

3.1. Expression, Purification, and Characterization of MPXV Proteins

3.2. Immunogenicity of Nanoemulsion Adjuvanted Subunit Vaccines in Mice

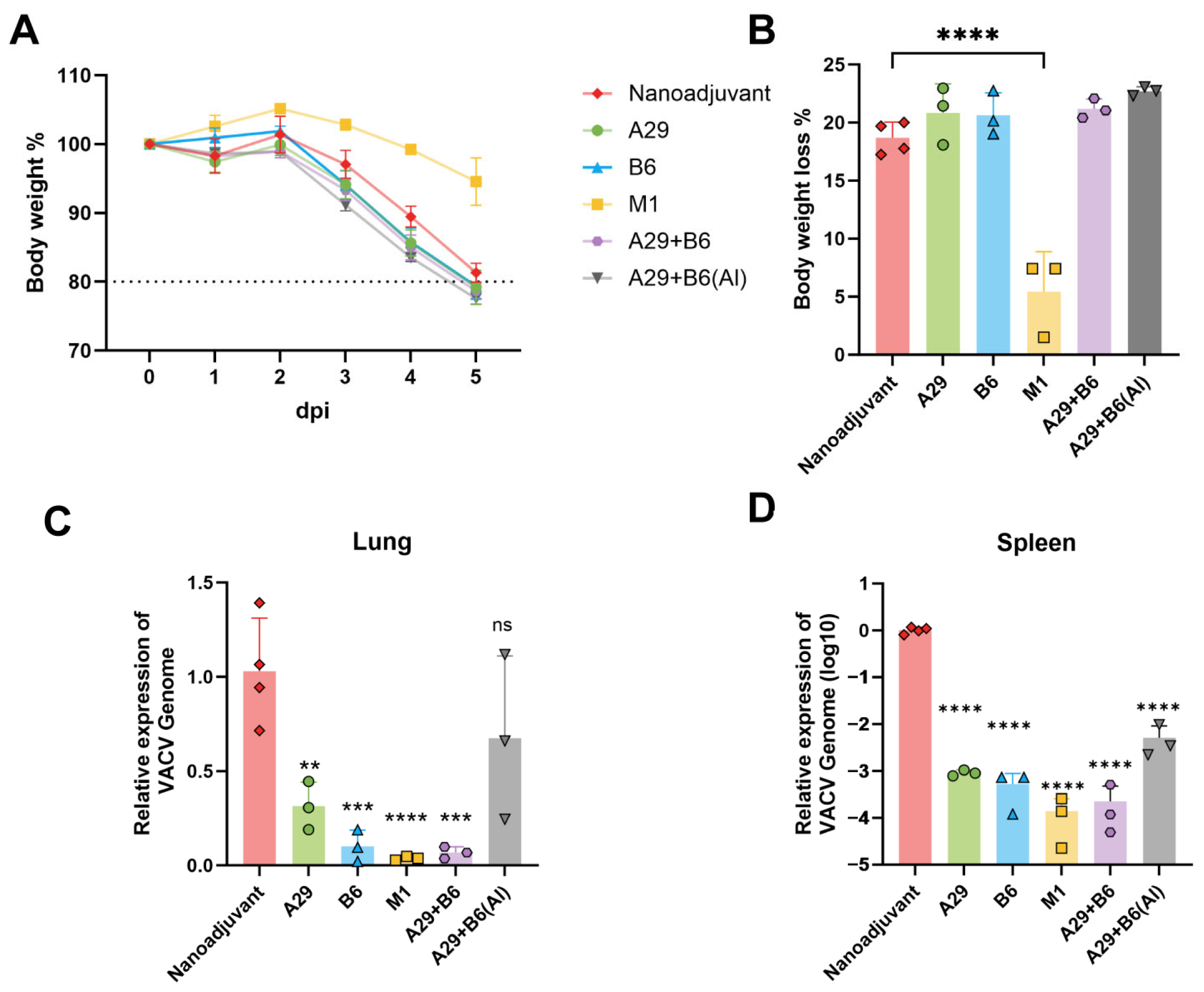

3.3. Protection Against Lethal MPXV Challenge

3.4. Cross-Protective Against Lethal VACV-WR Challenge

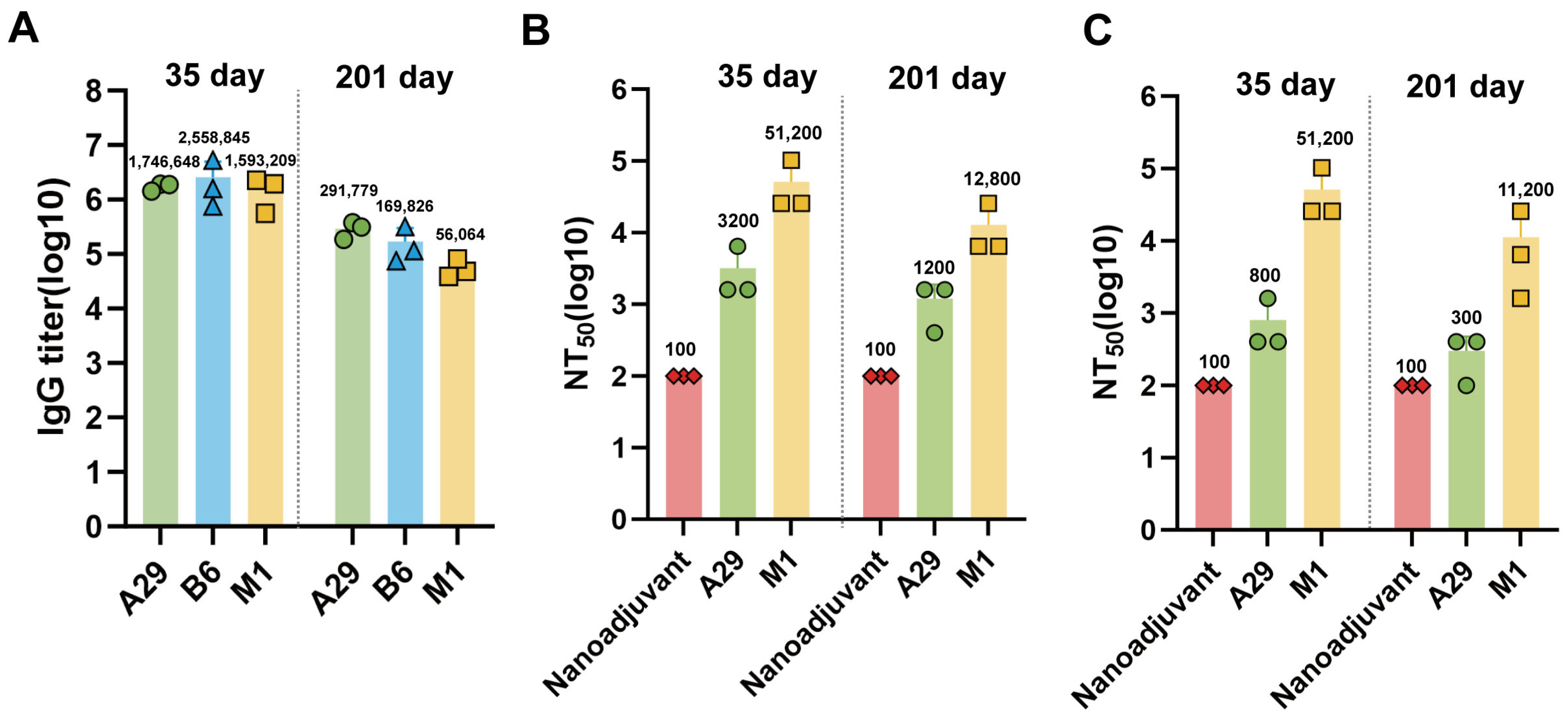

3.5. Long-Term Humoral Immune Responses Induced by Nanoemulsion Adjuvanted Subunit Vaccines

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lum, F.-M.; Torres-Ruesta, A.; Tay, M.Z.; Lin, R.T.P.; Lye, D.C.; Rénia, L.; Ng, L.F.P. Monkeypox: Disease Epidemiology, Host Immunity and Clinical Interventions. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetifa, I.; Muyembe, J.-J.; Bausch, D.G.; Heymann, D.L. Mpox Neglect and the Smallpox Niche: A Problem for Africa, a Problem for the World. Lancet 2023, 401, 1822–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornhill, J.P.; Barkati, S.; Walmsley, S.; Rockstroh, J.; Antinori, A.; Harrison, L.B.; Palich, R.; Nori, A.; Reeves, I.; Habibi, M.S.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans across 16 Countries—April–June 2022. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumla, A.; Valdoleiros, S.R.; Haider, N.; Asogun, D.; Ntoumi, F.; Petersen, E.; Kock, R. Monkeypox Outbreaks Outside Endemic Regions: Scientific and Social Priorities. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhdeo, S.; Mishra, S.; Walmsley, S. Human Monkeypox: A Comparison of the Characteristics of the New Epidemic to the Endemic Disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epidemiological Update—Week 35/2024: Mpox Due to Monkeypox Virus Clade I. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/mpox-epidemiological-update-monkeypox-2-september-2024 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Ahmed, S.K.; Ahmed Rashad, E.A.; Mohamed, M.G.; Ravi, R.K.; Essa, R.A.; Abdulqadir, S.O.; Khdir, A.A. The Global Human Monkeypox Outbreak in 2022: An Overview. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 104, 106794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.K.; Petersen, B.W.; Whitehill, F.; Razeq, J.H.; Isaacs, S.N.; Merchlinsky, M.J.; Campos-Outcalt, D.; Morgan, R.L.; Damon, I.; Sánchez, P.J.; et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for Preexposure Vaccination of Persons at Risk for Occupational Exposure to Orthopoxviruses: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, J.M.; Muller, S. Monkeypox: Potential Vaccine Development Strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, M.; Mandal, R.K.; Sikander, M.; Khan, M.R.; Haque, S.; Nagda, N.; Ahmad, F.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Safety and Efficacy of Repurposed Smallpox Vaccines Against Mpox: A Critical Review of ACAM2000, JYNNEOS, and LC16. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billioux, B.J.; Mbaya, O.T.; Sejvar, J.; Nath, A. Neurologic Complications of Smallpox and Monkeypox: A Review. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, R.A.; Shrestha, A.B.; Elsayed, M.; Memish, Z.A. Monkeypox Vaccination: Does It Cause Neurologic and Psychiatric Manifestations?—Correspondence. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 106, 106926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, R.N.; Overton, E.T.; Haas, D.W.; Frank, I.; Goldman, M.; von Krempelhuber, A.; Virgin, G.; Bädeker, N.; Vollmar, J.; Chaplin, P. Safety, Immunogenicity, and Surrogate Markers of Clinical Efficacy for Modified Vaccinia Ankara as a Smallpox Vaccine in HIV-Infected Subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, F.; Jiang, T.; Duan, J.; Huang, T.; Liu, H.; Jia, L.; Jia, H.; Yan, B.; Zhang, M.; et al. Human Mpox Co-Infection with Advanced HIV-1 and XDR-TB in a MSM Patient Previously Vaccinated against Smallpox: A Case Report. Biosaf. Health 2024, 6, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B.; Tosh, P.K. Prevention of Monkeypox with Vaccines: A Rapid Review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e349–e358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Yamamoto, K. Mpox in People with HIV: A Narrative Review. HIV Med. 2024, 25, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Monteiro, V.S.; Renauer, P.A.; Shang, X.; Suzuki, K.; Ling, X.; Bai, M.; Xiang, Y.; Levchenko, A.; Booth, C.J.; et al. Polyvalent mRNA Vaccination Elicited Potent Immune Response to Monkeypox Virus Surface Antigens. Cell Res. 2023, 33, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Du, P.; Ma, R.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Lu, J.; Gao, Z.; Qi, H.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; et al. Single-Chain A35R-M1R-B6R Trivalent mRNA Vaccines Protect Mice against Both Mpox Virus and Vaccinia Virus. eBioMedicine 2024, 109, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Atutxa, I.; Mondragon-Teran, P.; Huerta-Saquero, A.; Villanueva-Flores, F. Advancements in Monkeypox Vaccines Development: A Critical Review of Emerging Technologies. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1456060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghith, A.A.; Cotter, C.A.; Ignacio, M.A.; Earl, P.L.; Hills, R.A.; Howarth, M.R.; Yee, D.S.; Brenchley, J.M.; Moss, B. Mpox Multiprotein Virus-like Nanoparticle Vaccine Induces Neutralizing and Protective Antibodies in Mice and Non-Human Primates. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadh, M.J.; Ghadimkhani, T.; Soltani, N.; Abbassioun, A.; Daniel Cosme Pecho, R.; Taha, A.; Jwad Kazem, T.; Yasamineh, S.; Gholizadeh, O. Progress and Prospects on Vaccine Development against Monkeypox Infection. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 180, 106156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.G.; Orr, M.T.; Fox, C.B. Key Roles of Adjuvants in Modern Vaccines. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Chen, M.; Bian, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tong, R.; Sun, X. Advanced Subunit Vaccine Delivery Technologies: From Vaccine Cascade Obstacles to Design Strategies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 3321–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollet, J.; Chen, W.-H.; Strych, U. Recombinant Protein Vaccines, a Proven Approach against Coronavirus Pandemics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 170, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrack, P.; McKee, A.S.; Munks, M.W. Towards an Understanding of the Adjuvant Action of Aluminium. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awate, S.; Babiuk, L.A.; Mutwiri, G. Mechanisms of Action of Adjuvants. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Luan, N.; Yin, X.; Lin, K.; Liu, C. An Established Th2-Oriented Response to an Alum-Adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 Subunit Vaccine Is Not Reversible by Sequential Immunization with Nucleic Acid-Adjuvanted Th1-Oriented Subunit Vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, J.L.; Lavelle, E.C. Resolving Adjuvant Mode of Action to Enhance Vaccine Efficacy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2022, 77, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio, E.; D’Oro, U.; Wack, A. Immunology of TLR-Independent Vaccine Adjuvants. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009, 21, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, X.; Wei, Y.; Yu, Y.; Tian, X. Vaccine Adjuvants: Mechanisms and Platforms. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulendran, B.; Arunachalam, P.S.; O’hAgan, D.T. Emerging Concepts in the Science of Vaccine Adjuvants. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.B.; Baldwin, S.L.; Duthie, M.S.; Reed, S.G.; Vedvick, T.S. Immunomodulatory and Physical Effects of Oil Composition in Vaccine Adjuvant Emulsions. Vaccine 2011, 29, 9563–9572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, Y.J.; Kim, S.; Wickramasinghe, A.; Kim, J.; Song, J.; Kim, Y.-I.; Gil, J.; Noh, Y.-W.; Lee, M.-H.; Oh, S.-S.; et al. Multiscale Dynamic Immunomodulation by a Nanoemulsified Trojan-TLR7/8 Adjuvant for Robust Protection against Heterologous Pandemic and Endemic Viruses. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, S.; Didierlaurent, A.; Bourguignon, P.; Delhaye, S.; Baras, B.; Jacob, V.; Planty, C.; Elouahabi, A.; Harvengt, P.; Carlsen, H.; et al. Adjuvant System AS03 Containing α-Tocopherol Modulates Innate Immune Response and Leads to Improved Adaptive Immunity. Vaccine 2011, 29, 2461–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassaidy, B.J.; Moser, B.A.; Solanki, A.; Chen, Q.; Shen, J.; Gotsis, K.; Lockhart, Z.; Rutledge, N.; Rosenberger, M.G.; Dong, Y.; et al. Immune Potentiation of PLGA Controlled-Release Vaccines for Improved Immunological Outcomes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 11608–11614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Y.; Kobiyama, K.; Hayashi, T.; Onishi, M.; Yanagida, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Nishinaka, A.; Hirose, J.; Asaoka, Y.; et al. A-910823, a Squalene-Based Emulsion Adjuvant, Induces T Follicular Helper Cells and Humoral Immune Responses via α-Tocopherol Component. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1116238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, P.; Qu, A.; Sun, M.; Xu, L.; Xu, C.; Hu, S.; Kuang, H. Opportunities and Challenges for Nanomaterials as Vaccine Adjuvants. Small Methods 2025, 9, 2402059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Sun, J.; Song, T.-Z.; Liu, T.; Tang, F.; Zhang, X.; Ding, L.; Miao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Pan, X.; et al. CoVac501, a Self-Adjuvanting Peptide Vaccine Conjugated with TLR7 Agonists, against SARS-CoV-2 Induces Protective Immunity. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, B.; Bing, J.; Wang, T.; Han, R.; Huo, S.; Sun, S.; Zhao, L.; Shu, C.; et al. Rational Mpox Vaccine Design: Immunogenicity and Protective Effect of Individual and Multicomponent Proteins in Mice. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2482702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Tai, W.; Ma, E.; Jiang, Q.; Fan, M.; Xiao, W.; Tian, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Generation and Characterization of Neutralizing Antibodies against M1R and B6R Proteins of Monkeypox Virus. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interim Recommendations for the Use of Protein Subunit COVID-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-protein_subunit-2023.1 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- de Pinho Favaro, M.T.; Atienza-Garriga, J.; Martínez-Torró, C.; Parladé, E.; Vázquez, E.; Corchero, J.L.; Ferrer-Miralles, N.; Villaverde, A. Recombinant Vaccines in 2022: A Perspective from the Cell Factory. Microb. Cell. Factories 2022, 21, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Storage and Handling of Immunobiologics. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/imz-best-practices/storage-handling-immunobiologics.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Protopapas, K.; Dimopoulou, D.; Kalesis, N.; Akinosoglou, K.; Moschopoulos, C.D. Mpox and Lessons Learned in the Light of the Recent Outbreak: A Narrative Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Han, X.; Zhao, J.; Gu, G.; Fang, M.; et al. Mpox Multi-Antigen mRNA Vaccine Candidates by a Simplified Manufacturing Strategy Afford Efficient Protection against Lethal Orthopoxvirus Challenge. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2204151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Zhang, R.; Shen, T.; Li, A.; Hou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, B.; Sun, P.; Gong, X.; et al. Systematic Evaluation of the Induction of Efficient Neutralizing Antibodies by Recombinant Multicomponent Subunit Vaccines against Monkeypox Virus. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Trower, A.; Garcia, A.; Meseda, C.A.; He, Y.; Weiss, C.; Kumar, A.; Weir, J.P.; Merchlinsky, M. Identification and Preliminary Characterization of Vaccinia Virus (Dryvax) Antigens Recognized by Vaccinia Immune Globulin. Virology 2005, 343, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Dong, J.; Wei, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, G.; Xu, M.; Zhao, A. Enhanced Immune Responses in Mice by Combining the Mpox Virus B6R-Protein and Aluminum Hydroxide-CpG Vaccine Adjuvants. Vaccines 2024, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Liu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, Z.; Wang, D.; Tang, W.; He, Y.; Zheng, X.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. Immune Responses and Protective Efficacy of Nanoemulsion-Adjuvanted Monkeypox Virus Recombinant Vaccines Against Lethal Challenge in Mice. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121293

Zhang C, Liu N, Zhao Y, Pan Z, Wang D, Tang W, He Y, Zheng X, Qi Z, Zhang X, et al. Immune Responses and Protective Efficacy of Nanoemulsion-Adjuvanted Monkeypox Virus Recombinant Vaccines Against Lethal Challenge in Mice. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121293

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Congcong, Nuo Liu, Yanqi Zhao, Zhendong Pan, Dawei Wang, Wanda Tang, Yanhua He, Xu Zheng, Zhongtian Qi, Xinxin Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Immune Responses and Protective Efficacy of Nanoemulsion-Adjuvanted Monkeypox Virus Recombinant Vaccines Against Lethal Challenge in Mice" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121293

APA StyleZhang, C., Liu, N., Zhao, Y., Pan, Z., Wang, D., Tang, W., He, Y., Zheng, X., Qi, Z., Zhang, X., & Zhao, P. (2025). Immune Responses and Protective Efficacy of Nanoemulsion-Adjuvanted Monkeypox Virus Recombinant Vaccines Against Lethal Challenge in Mice. Pathogens, 14(12), 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121293