Er:YAG Laser Energy Optimization for Reducing Single-Species Microbial Growth on Agar Surfaces In Vitro

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Rationale

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- Phase I: Mapping inhibition zone formation at graded energy levels.

- Phase II: Assessing reduction in viable surface coverage in mature agar-based cultures.

2.2. Null Hypothesis

2.3. Objectives

- To measure the relationship between laser energy and inhibition zone diameter across different microbial species.

- To quantify the reduction in viable microbial growth at defined laser energy settings.

- To compare the performance of tapered and flat laser tips in energy delivery and antimicrobial effectiveness.

2.4. Bacterial and Fungal Strains

2.5. Cultivation Conditions

2.6. Study Groups

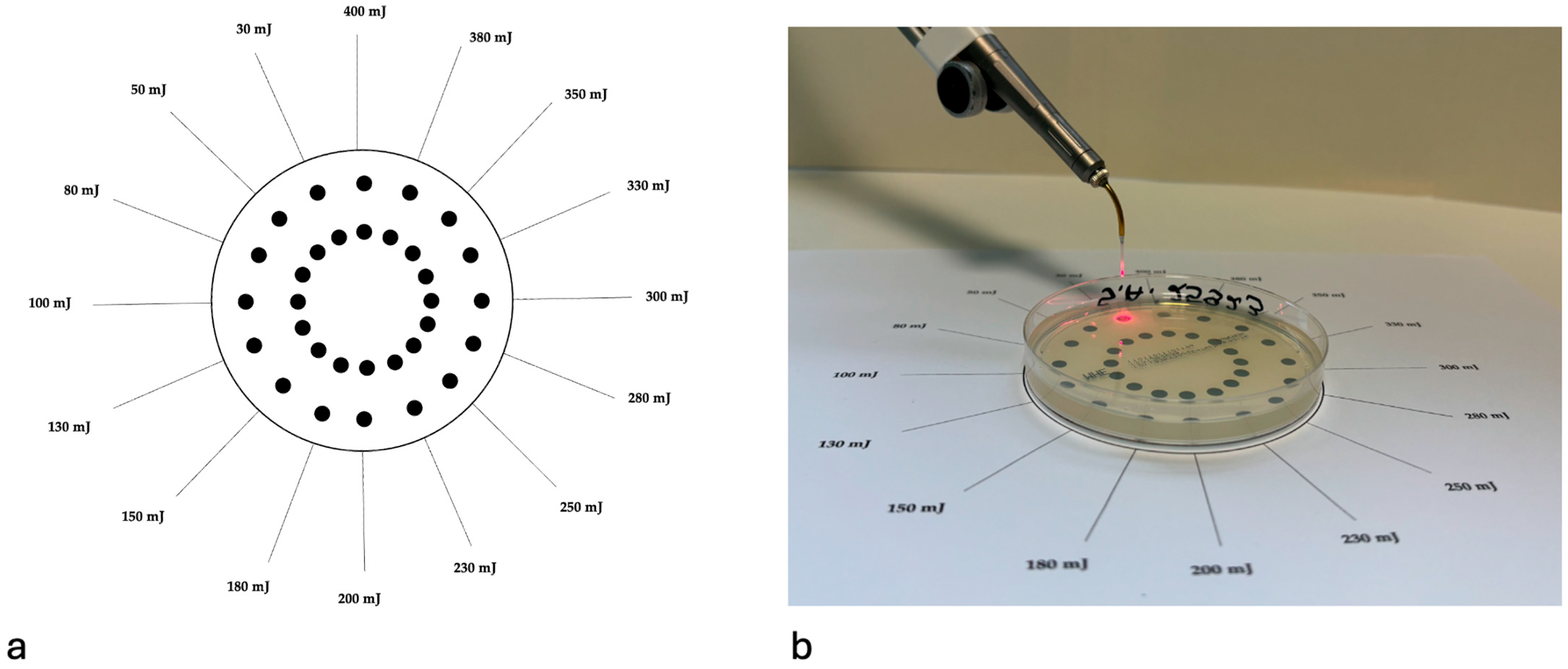

2.7. Assessment of the Antimicrobial Effectiveness of Er:YAG Laser Irradiation on Single-Species Culture Growth

2.7.1. Agar-Based Microbial Surface Layer

2.7.2. Laser Irradiation Protocol

2.7.3. Incubation and Imaging

2.7.4. Quantitative Analysis

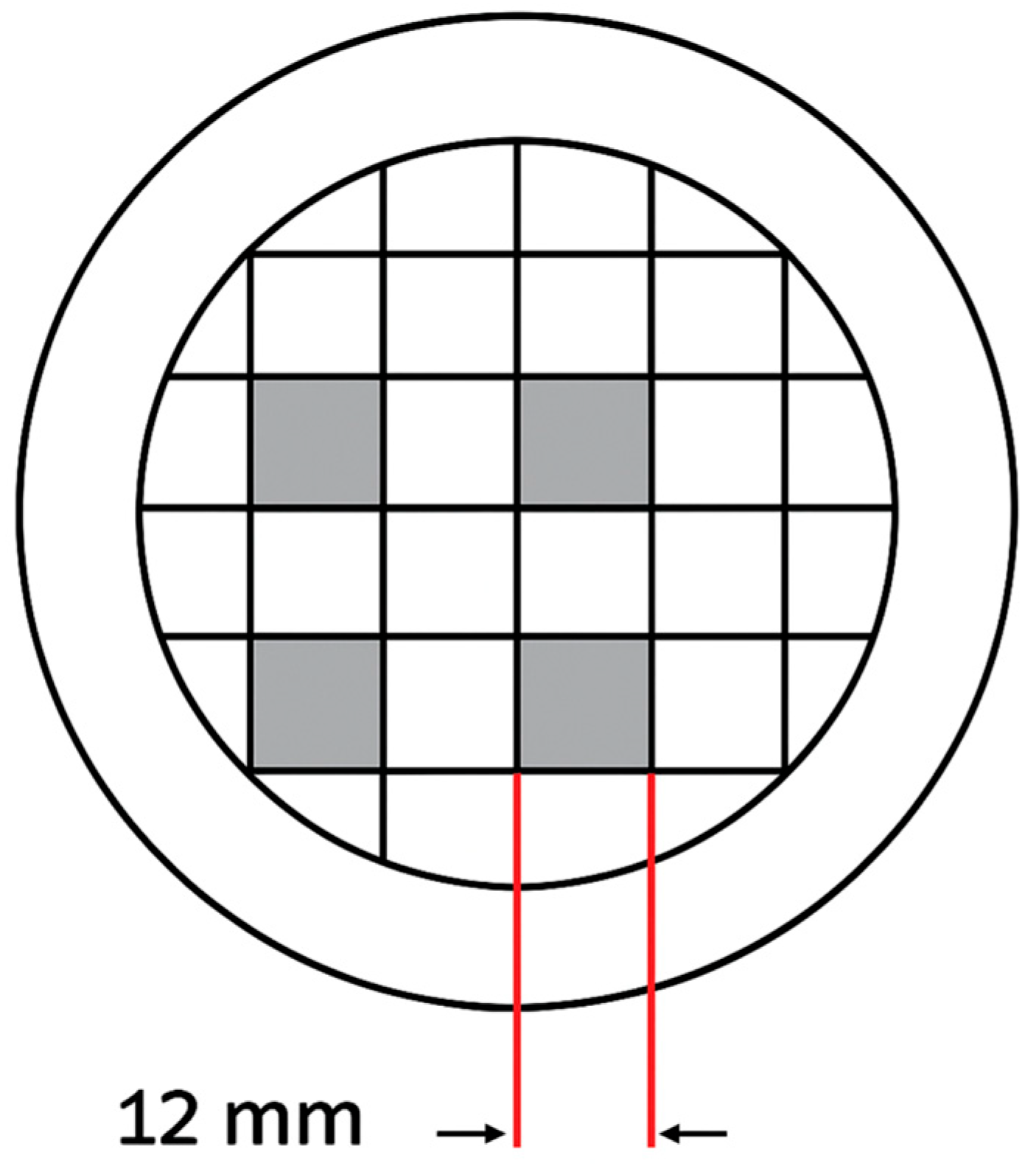

2.8. Assessment of the Er:YAG Laser’s Effectiveness in Removing Mature Single-Species Cultures

2.8.1. Culture Maturation

2.8.2. Laser Irradiation Procedure

2.8.3. Sampling and Incubation

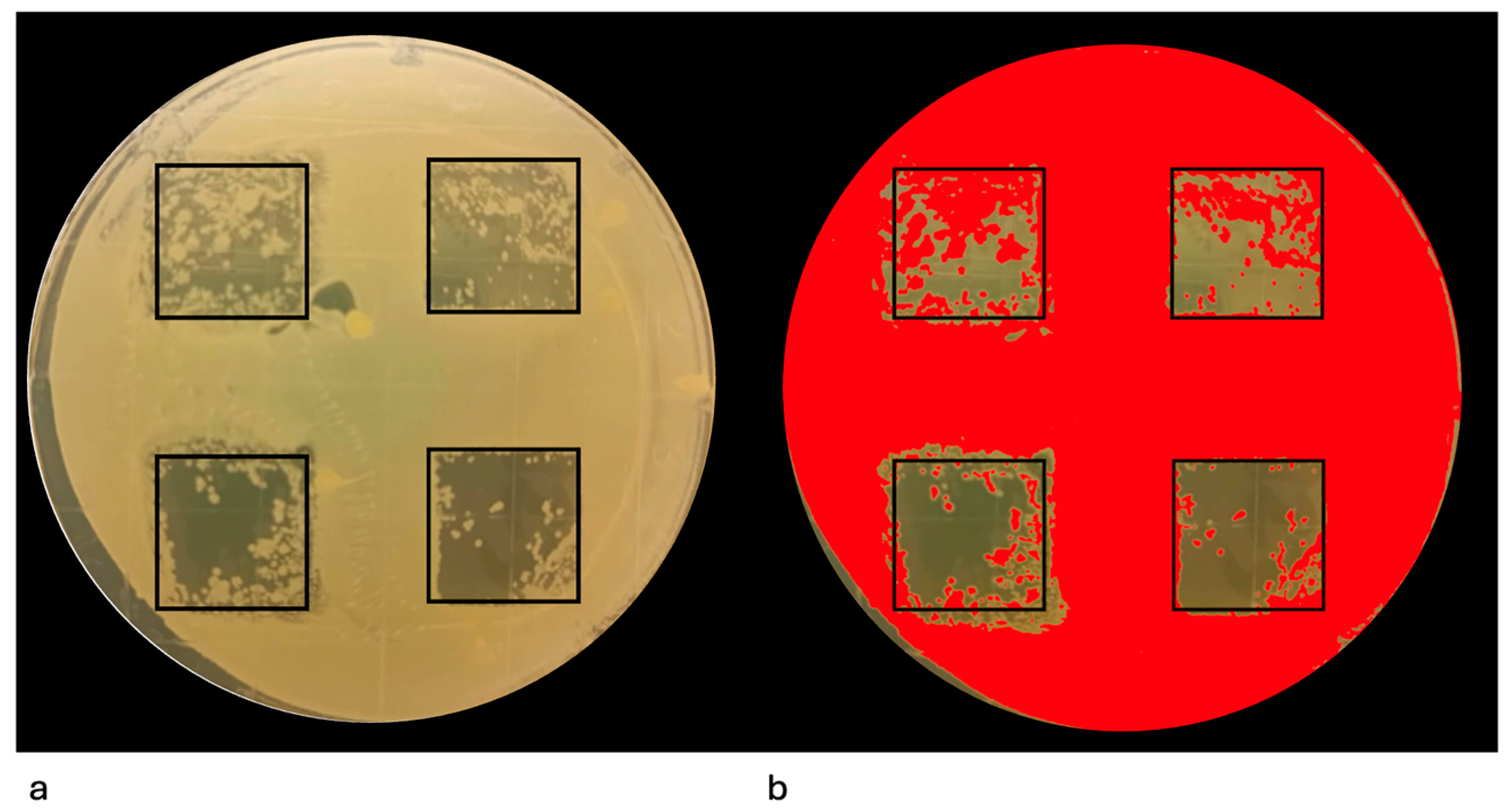

2.8.4. Image Acquisition and Quantitative Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

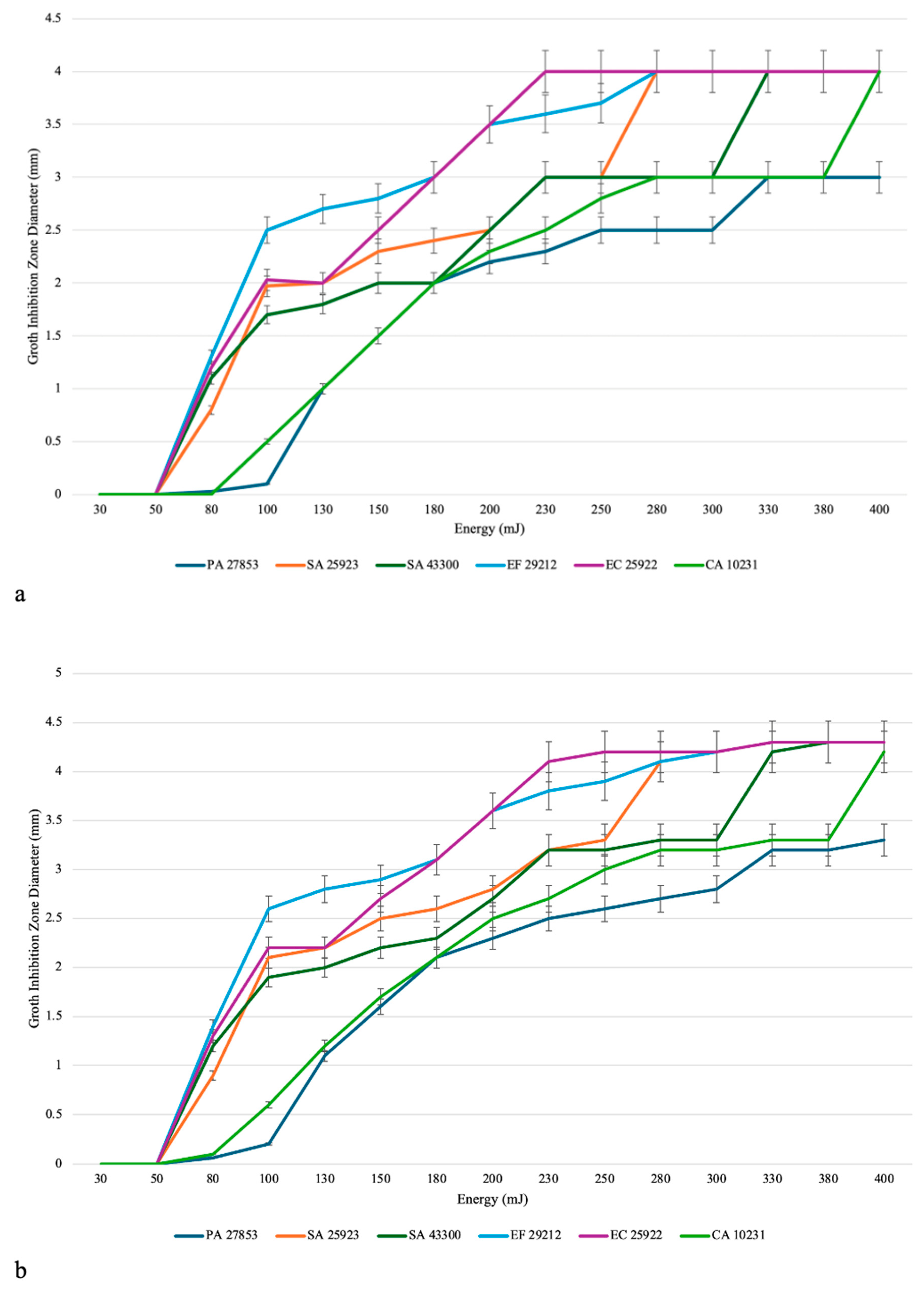

3.1. Evaluation of the Efficacy of the Er:YAG Laser in Inhibiting the Growth of Single-Species Cultures

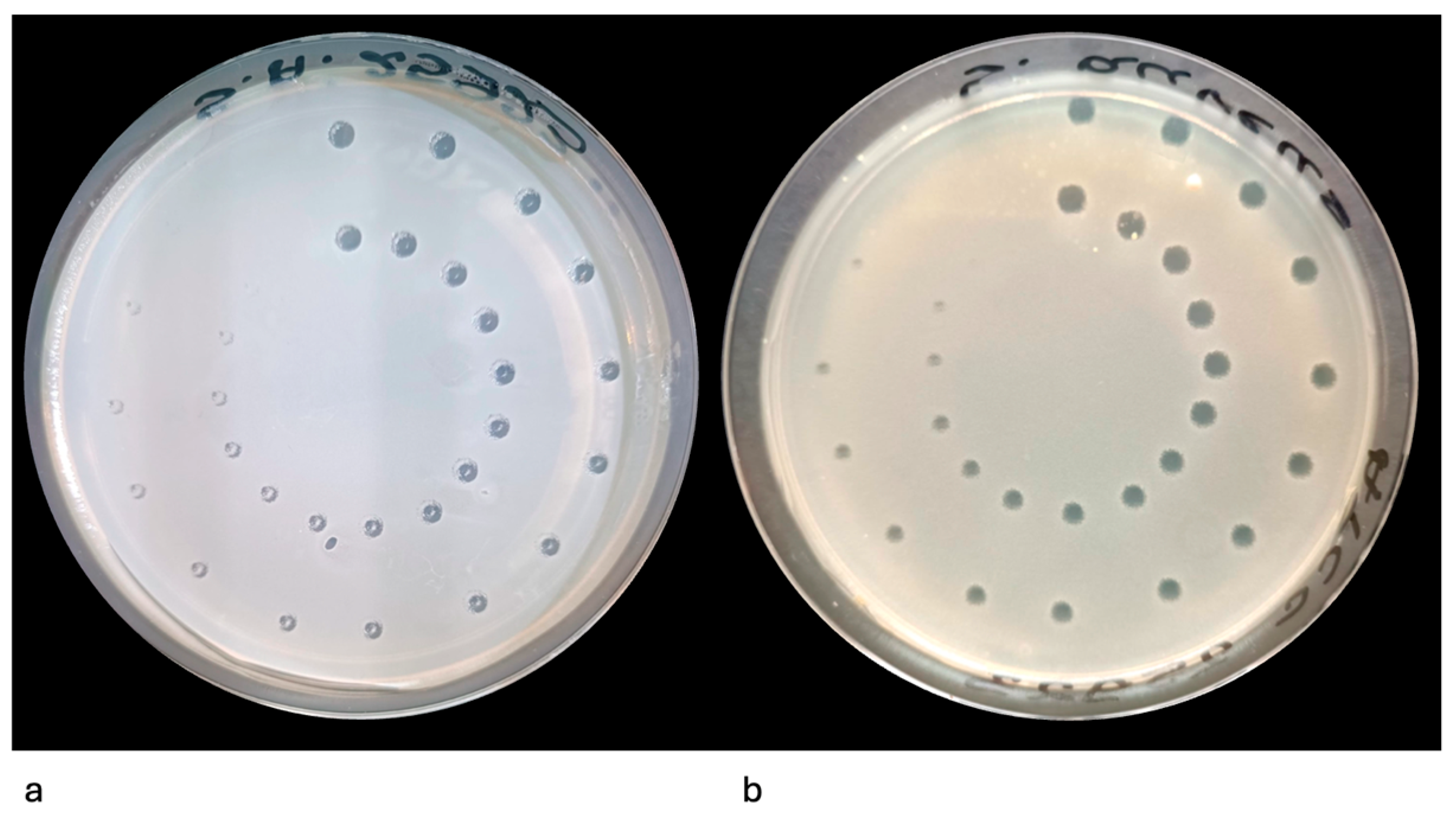

3.2. Evaluation of the Efficacy of the Er:YAG Laser in Eliminating Mature Single-Species Agar Culture

3.3. Finding the Optimal Parameters for the In Vitro Eradication of Each Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Results in the Context of Evidence

4.2. Clinical Relevance and Broader Translation

4.3. Limitations of the Study

4.4. Significance of the Study

4.5. Clinical Translation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Er:YAG | Erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet |

| Nd:YAG | Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substance |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MSSA | Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| TSA | Tryptic Soy Agar |

| SDA | Sabouraud Dextrose Agar |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| GIZ | Growth inhibition zone |

| PA | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| SA | Staphylococcus aureus |

| EF | Enterococcus faecalis |

| EC | Escherichia coli |

| CA | Candida albicans |

References

- Jiao, Y.; Tay, F.R.; Niu, L.N.; Chen, J.H. Advancing antimicrobial strategies for managing oral biofilm infections. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzman, G.M.; Horowitz, R.A.; Johnson, R.; Prestiano, R.A.; Klein, B.I. The systemic oral health connection: Biofilms. Medicine 2022, 101, e30517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolini, M.; Costa, R.C.; Barão, V.A.R.; Villar, C.C.; Retamal-Valdes, B.; Feres, M.; Souza, J.G.S. Oral microorganisms and biofilms: New insights to defeat the main etiologic factor of oral diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaddad, S.A.; Tahmasebi, E.; Yazdanian, A.; Rezvani, M.B.; Seifalian, A.; Yazdanian, M.; Tebyanian, H. Oral microbial biofilms: An update. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 2005–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurnheer, T.; Paqué, P.N. Biofilm models to study the etiology and pathogenesis of oral diseases. Monogr. Oral Sci. 2021, 29, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Understanding bacterial biofilms: From definition to treatment strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Mohammed, M.M.; Pettersen, V.K.; Nerland, A.H.; Wiker, H.G.; Bakken, V. Label-free quantitative proteomic analysis of the oral bacteria Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis to identify protein features relevant in biofilm formation. Anaerobe 2021, 72, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mohler, J.; Mahajan, S.D.; Schwartz, S.A.; Bruggemann, L.; Aalinkeel, R. Microbial biofilm: A review on formation, infection, antibiotic resistance, control measures, and innovative treatment. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirghani, R.; Saba, T.; Khaliq, H.; Mitchell, J.; Do, L.; Chambi, L.; Diaz, K.; Kennedy, T.; Alkassab, K.; Huynh, T.; et al. Biofilms: Formation, drug resistance and alternatives to conventional approaches. AIMS Microbiol. 2022, 8, 239–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, N.; Joo, S.W.; Mandal, T.K. Nanomaterial-based strategies to combat antibiotic resistance: Mechanisms and applications. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Misba, L.; Khan, A.U. Antibiotics versus biofilm: An emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Trinchera, M.; Midiri, A.; Zummo, S.; Vitale, G.; Biondo, C. Novel antimicrobial approaches to combat bacterial biofilms associated with urinary tract infections. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niño-Vega, G.A.; Ortiz-Ramírez, J.A.; López-Romero, E. Novel antibacterial approaches and therapeutic strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Mi, G.; Wang, M.; Webster, T.J. In Vitro and Ex Vivo systems at the forefront of infection modeling and drug discovery. Biomaterials 2019, 198, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles Flores, G.; Cusumano, G.; Venanzoni, R.; Angelini, P. Advancements in antibacterial therapy: Feature papers. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Antimicrobial efficacy of Nd:YAG laser in polymicrobial root canal infections: A systematic review of In Vitro studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, Z.; Tkaczyk, M.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Zawilska, A.; Wiench, R. Enhancing root canal disinfection with Er:YAG laser: A systematic review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Skaba, D.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Wiench, R. Antibacterial and bactericidal effects of the Er: YAG laser on oral bacteria: A systematic review of microbiological evidence. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsamee, N. Soft and hard dental tissues laser Er:YAG laser: From fundamentals to clinical applications. EC Dent. Sci. 2017, 11, 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dembicka-Mączka, D.; Kępa, M.; Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, Z.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Wiench, R. Evaluation of the disinfection efficacy of Er: YAG laser light on single-species Candida biofilms: An In Vitro study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzech-Leśniak, Z.; Pyrkosz, J.; Szwach, J.; Kosidło, P.; Matys, J.; Wiench, R.; Pajączkowska, M.; Nowicka, J.; Dominiak, M.; Grzech-Leśniak, K. Antibacterial effects of Er:YAG laser irradiation on Candida-streptococcal biofilms. Life 2025, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoharib, H. Erbium-Doped Yttrium Aluminium Garnet (Er:YAG) Lasers in the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis. Cureus 2025, 17, e78279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosun, E.; Tasar, F.; Strauss, R.; Kıvanc, D.G.; Ungor, C. Comparative evaluation of antimicrobial effects of Er:YAG, diode and CO2 lasers on titanium discs: An experimental study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojaver, S.; Fiorellini, J.; Sarmiento, H. Advancing Peri-Implantitis Treatment: A Scoping Review of Breakthroughs in Implantoplasty and Er:YAG Laser Therapies. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2025, 11, e70104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladeinde, A.; Lipp, E.; Chen, C.Y.; Muirhead, R.; Glenn, T.; Cook, K.; Molina, M. Transcriptome changes of Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis and Escherichia coli O157:H7 laboratory strains in response to photo-degraded DOM. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folwaczny, M.; Mehl, A.; Aggstaller, H.; Hickel, R. Antimicrobial effects of 2.94 μm Er:YAG laser radiation on root surfaces: An In Vitro study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002, 29, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meire, M.A.; Coenye, T.; Nelis, H.J.; De Moor, R.J. In Vitro inactivation of endodontic pathogens with Nd:YAG and Er:YAG lasers. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noiri, Y.; Katsumoto, T.; Azakami, H.; Ebisu, S. Effects of Er:YAG laser irradiation on biofilm-forming bacteria associated with endodontic pathogens In Vitro. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, C.; Pagano, S.; Bozza, S.; Ciurnella, E.; Lomurno, G.; Capobianco, B.; Coniglio, M.; Cianetti, S.; Marinucci, L. Use of the Er:YAG laser in conservative dentistry: Evaluation of the microbial population in carious lesions. Materials 2021, 14, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almatroudi, A. Biofilm resilience: Molecular mechanisms driving antibiotic resistance in clinical contexts. Biology 2025, 14, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, F.; Fratianni, F.; Bianco, V.; Wang, Z.; Pellegrini, M.; Coppola, R.; Nazzaro, F. New methodologies as opportunities in the study of bacterial biofilms, including food-related applications. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, L.; Jean-Pierre, F.; Côté, J.P. Building microbial communities to improve antimicrobial strategies. NPJ Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Shi, L.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, S. Comparison of clinical parameters, microbiological effects and calprotectin counts in gingival crevicular fluid between Er:YAG laser and conventional periodontal therapies. Medicine 2017, 96, e9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurpegui Abud, D.; Shariff, J.A.; Linden, E.; Kang, P.Y. E Erbium-doped: Yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Er:YAG) versus scaling and root planing for the treatment of periodontal disease: A single-blinded split-mouth randomized clinical trial. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Zhang, D.; Song, Y.; Wang, Z. Efficacy of Er:YAG laser on periodontitis as an adjunctive non-surgical treatment: A split-mouth randomized controlled study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yin, Y.; Tao, L.; Nie, P.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, M. Er:YAG laser versus scaling and root planing as alternative or adjuvant for chronic periodontitis treatment: A systematic review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgolastra, F.; Petrucci, A.; Gatto, R.; Monaco, A. Efficacy of Er:YAG laser in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavu, V.; Kumar, D.; Krishnakumar, D.; Maheshkumar, A.; Agarwal, A.; Kirubakaran, R.; Muthu, M.S. Erbium lasers in non-surgical periodontal therapy: An umbrella review and evidence gap map analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Sánchez, I.; Ortiz-Vigón, A.; Matos, R.; Herrera, D.; Sanz, M. Clinical efficacy of subgingival debridement with adjunctive Er:YAG laser treatment in chronic periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Jia, X.; Zhou, X. Combined application of Er:YAG laser and low-level laser in non-surgical treatment of periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2025, 96, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonzetich, J. Production and origin of oral malodor: A review of mechanisms and methods of analysis. J. Periodontol. 1977, 48, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortelli, J.R.; Barbosa, M.D.S.; Westphal, M.A. Halitosis: A review of associated factors and therapeutic approaches. Braz. Oral Res. 2008, 22, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, A.; Zaitsu, T.; Ueno, M.; Kawaguchi, Y. Characterization of oral bacteria in the tongue coating of patients with halitosis using 16S rRNA analysis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2020, 78, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggio, M.P.; Lennon, A.; Rolph, H.J.; Hodge, P.; Donaldson, A.; Maxwell, A.; Bagg, J. Molecular identification of bacteria on the tongue dorsum of subjects with and without halitosis. Oral Dis. 2008, 14, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Kępa, M.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Er:YAG Laser Energy Optimization for Reducing Single-Species Microbial Growth on Agar Surfaces In Vitro. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121287

Fiegler-Rudol J, Kępa M, Skaba D, Wiench R. Er:YAG Laser Energy Optimization for Reducing Single-Species Microbial Growth on Agar Surfaces In Vitro. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121287

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiegler-Rudol, Jakub, Małgorzata Kępa, Dariusz Skaba, and Rafał Wiench. 2025. "Er:YAG Laser Energy Optimization for Reducing Single-Species Microbial Growth on Agar Surfaces In Vitro" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121287

APA StyleFiegler-Rudol, J., Kępa, M., Skaba, D., & Wiench, R. (2025). Er:YAG Laser Energy Optimization for Reducing Single-Species Microbial Growth on Agar Surfaces In Vitro. Pathogens, 14(12), 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121287