The Use of Point-of-Care Tests and Multiplex PCR Tests in the Pediatric Emergency Department Reduces Antibiotic Prescription in Patients with Febrile Acute Respiratory Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Rapid and Microbiological Diagnostic Test

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARIs | Acute Respiratory Infections |

| PED | Pediatric Emergency Department |

| URTIs | Upper Respiratory Tract Infections |

| POCTs | Point-of-Care Tests |

| GAS-RAD | Group A Streptococcus rapid antigen detection |

| RSV-RAD | Respiratory Syncytial Virus rapid antigen detection |

| DFAs | Direct Immunofluorescence Assays |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| CRP-POC | C-Reactive Protein Point-of-Care |

| LOS | Length Of Stay |

| SSO | Short-Stay Observation |

| CXRs | Chest X-rays |

| CRREM | Regional Reference Center for Microbiological Emergencies |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| SpO2 | Saturation of Peripheral Oxygen |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| OR | Odds Rate |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- Sands, R.; Shanmugavadivel, D.; Stephenson, T.; Wood, D. Medical Problems Presenting to Paediatric Emergency Departments: 10 Years On. Emerg. Med. J. 2012, 29, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, N.N.; Borensztajn, D.M.; Nijman, R.; Balode, A.; Von Both, U.; Carrol, E.D.; Eleftheriou, I.; Emonts, M.; Van Der Flier, M.; De Groot, R.; et al. Variation in Antibiotic Prescription Rates in Febrile Children Presenting to Emergency Departments across Europe (MOFICHE): A Multicentre Observational Study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.K.; Gebretsadik, T.; Carroll, K.N.; Dupont, W.D.; Mohamed, Y.A.; Morin, L.-L.; Heil, L.; Minton, P.A.; Woodward, K.; Liu, Z.; et al. Viral Etiologies of Infant Bronchiolitis, Croup and Upper Respiratory Illness During 4 Consecutive Years. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013, 32, 950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Yang, L.; Lou, C.T.; Yang, F.; SiTou, K.I.; Hu, H.; Io, K.; Cheok, K.T.; Pan, B.; Ung, C.O.L. Viral Etiology and Epidemiology of Pediatric Patients Hospitalized for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections in Macao: A Retrospective Study from 2014 to 2017. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer Sauteur, P.M. Childhood Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 183, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, P.G.M.; Britto, M.C.A.; Correia, J.B.; Duarte, M.D.C.M.B.; Fonceca, A.M.; Rose, K.; Hopkins, M.J.; Cuevas, L.E.; McNamara, P.S. Viral and Atypical Bacterial Detection in Acute Respiratory Infection in Children Under Five Years. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Z.; Ehle, E.A.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, M. Systematic Review of Evidence-Based Guidelines on Medication Therapy for Upper Respiratory Tract Infection in Children with AGREE Instrument. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, J.S.; Byington, C.L.; Shah, S.S.; Alverson, B.; Carter, E.R.; Harrison, C.; Kaplan, S.L.; Mace, S.E.; McCracken, G.H.; Moore, M.R.; et al. The Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Children Older Than 3 Months of Age: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, e25–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable Deaths and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years Caused by Infections with Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A Population-Level Modelling Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donà, D.; Barbieri, E.; Brigadoi, G.; Liberati, C.; Bosis, S.; Castagnola, E.; Colomba, C.; Galli, L.; Lancella, L.; Lo Vecchio, A.; et al. State of the Art of Antimicrobial and Diagnostic Stewardship in Pediatric Setting. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellit, T.H.; Owens, R.C.; McGowan, J.E.; Gerding, D.N.; Weinstein, R.A.; Burke, J.P.; Huskins, W.C.; Paterson, D.L.; Fishman, N.O.; Carpenter, C.F.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Guidelines for Developing an Institutional Program to Enhance Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesters, K.; Buonsenso, D. Antimicrobial Stewardship in Pediatric Emergency Medicine: A Narrative Exploration of Antibiotic Overprescribing, Stewardship Interventions, and Performance Metrics. Children 2024, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drancourt, M.; Michel-Lepage, A.; Boyer, S.; Raoult, D. The Point-of-Care Laboratory in Clinical Microbiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigadoi, G.; Gastaldi, A.; Moi, M.; Barbieri, E.; Rossin, S.; Biffi, A.; Cantarutti, A.; Giaquinto, C.; Da Dalt, L.; Donà, D. Point-of-Care and Rapid Tests for the Etiological Diagnosis of Respiratory Tract Infections in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, A.M.; Brown, D.S.; Durkin, M.J.; Sahrmann, J.M.; Nickel, K.B.; O’neil, C.A.; Olsen, M.A.; Hyun, D.Y.; Zetts, R.M.; Newland, J.G. Association of Inappropriate Outpatient Pediatric Antibiotic Prescriptions with Adverse Drug Events and Health Care Expenditures. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, E2214153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, L. Point-of-Care Testing in Microbiology. Clin. Lab. Med. 2020, 40, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonkin-Crine, S.K.; Tan, P.S.; Van Hecke, O.; Wang, K.; Roberts, N.W.; McCullough, A.; Hansen, M.P.; Butler, C.C.; Del Mar, C.B. Clinician-Targeted Interventions to Influence Antibiotic Prescribing Behaviour for Acute Respiratory Infections in Primary Care: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2019, CD012252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.M.; Harper, J.; Broomfield, D.; Templeton, K.E. Rapid Testing for Respiratory Syncytial Virus in a Paediatric Emergency Department: Benefits for Infection Control and Bed Management. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 77, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, U.V.; Holm, M.K.A.; Bang, D.; Petersen, R.F.; Mortensen, S.; Trebbien, R.; Lisby, J.G. Point-of-Care Tests for Influenza A and B Viruses and RSV in Emergency Departments—Indications, Impact on Patient Management and Possible Gains by Syndromic Respiratory Testing, Capital Region, Denmark, 2018. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 1900430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedemark, S.A.; Aabenhus, R.; Llor, C.; Fournaise, A.; Olsen, O.; Jørgensen, K.J. Biomarkers as Point-of-Care Tests to Guide Prescription of Antibiotics in People with Acute Respiratory Infections in Primary Care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2022, CD010130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Laurich, V.M.; Smith, S.; Sturm, J. Point-of-Care Influenza Testing in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2020, 36, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, S.; Paalanne, N.; Honkila, M.; Pokka, T.; Tapiainen, T. Effect of Point-of-Care Testing for Respiratory Pathogens on Antibiotic Use in Children: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2216162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences.; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bronchiolitis in Children: Diagnosis and Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Alvarez, O. Acute Management of Croup in the Emergency Department. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 22, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossella, B.; Gagliotti, C.; Ricchizzi, E. Uso di Antibiotici e Resistenze Antimicrobiche in età Pediatrica; Rapporto Emilia-Romagna: Bologna, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Puntoni, M.; Caminiti, C.; Maglietta, G.; Lanari, M.; Biasucci, G.; Suppiej, A.; Marchetti, F.; De Fanti, A.; Caramelli, F.; Iughetti, L.; et al. Pediatric Healthcare Service Utilization after the End of COVID-19 State of Emergency in Northern Italy: A 6-Year Quasi-Experimental Study Using Interrupted Time-Series Analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1575047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, A.; Giombini, E.; Mateo Urdiales, A.; Caraglia, A.; Maraglino, F.; Facchini, M.; di Mario, G.; Piacentini, S.; Di Martino, A.; Fabiani, C.; et al. La sorveglianza integrata dei virus respiratori “RespiVirNet” in Italia: I risultati della stagione 2023–2024. Boll. Epidemiol. Naz. 2025, 5, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantoni, L.; Lasala, V.; Dondi, A.; Cifaldi, M.; Corsini, I.; Lanari, M.; Zama, D. Antibiotic Prescribing for Lower Respiratory Tract Infections and Community-Acquired Pneumonia: An Italian Pediatric Emergency Department’s Real-Life Experience. Life 2023, 13, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Maat, J.; Van De Voort, E.; Mintegi, S.; Gervaix, A.; Nieboer, D.; Moll, H.; Oostenbrink, R.; Moll, H.A.; Oostenbrink, R.; Van Veen, M.; et al. Antibiotic Prescription for Febrile Children in European Emergency Departments: A Cross-Sectional, Observational Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covino, M.; Buonsenso, D.; Gatto, A.; Morello, R.; Curatole, A.; Simeoni, B.; Franceschi, F.; Chiaretti, A. Determinants of Antibiotic Prescriptions in a Large Cohort of Children Discharged from a Pediatric Emergency Department. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 2017–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shu, T.; Li, W.; Shang, S.; Du, L. Epidemiological Study of Post-Pandemic Pediatric Common Respiratory Pathogens Using Multiplex Detection. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, E.; Di Chiara, C.; Costenaro, P.; Cantarutti, A.; Giaquinto, C.; Hsia, Y.; Doná, D. Antibiotic Prescribing Patterns in Paediatric Primary Care in Italy: Findings from 2012–2018. Antibiotics 2021, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, M.; Lallo, A.; Kirchmayer, U.; Davoli, M.; Fusco, D. Prevalence of Antibiotic Prescription in Pediatric Outpatients in Italy: The Role of Local Health Districts and Primary Care Physicians in Determining Variation. A Multilevel Design for Healthcare Decision Support. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatico-Guillon, L.; Shea, K.; Jafarzadeh, S.R.; Camelo, I.; Maakaroun-Vermesse, Z.; Figueira, M.; Adams, W.G.; Pelton, S. Antibiotic Prescribing in Outpatient Children: A Cohort From a Clinical Data Warehouse. Clin. Pediatr. 2019, 58, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Mencacci, A.; Cenci, E.; Camilloni, B.; Silvestri, E.; Principi, N. Multiplex Platforms for the Identification of Respiratory Pathogens: Are They Useful in Pediatric Clinical Practice? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Lamb, M.M.; Moss, A.; Mistry, R.D.; Grice, K.; Ahmed, W.; Santos-Cantu, D.; Kitchen, E.; Patel, C.; Ferrari, I.; et al. Effect of Rapid Respiratory Virus Testing on Antibiotic Prescribing Among Children Presenting to the Emergency Department With Acute Respiratory Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherif, B.; Hamza, H.M.; Abdelwahab, H.E.E. Impact of Nested Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay in the Management of Pediatric Patients with Acute Respiratory Tract Infections: A Single Center Experience. Infez. Med. 2023, 31, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunaratnam, L.C.; Robinson, J.L.; Hawkes, M.T. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Biomarkers for Pediatric Pneumonia. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2021, 10, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, N.A.; Keizer, E.; Plate, A.; Coenen, S.; Valeri, F.; Verbakel, J.Y.J.; Rosemann, T.; Neuner-Jehle, S.; Senn, O. Point-of-Care C-Reactive Protein Testing to Reduce Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Tract Infections in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, D.; Hochart, A.; Lagree, M.; Dervaux, B.; Martinot, A.; Dubos, F. Impact of the Sofia® Influenza A+B FIA Rapid Diagnostic Test in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Arch. Pédiatr. 2019, 26, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, T.; Fueri, E.; Formigoni, C.; Mariani, M.; Villa, G.; Finetti, M.; Marin, M.; De Chiara, E.; Bratta, A.; Vanorio, B.; et al. Usefulness of Point-of-Care Testing for Respiratory Viruses in a Pediatric Emergency Department Setting. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Dewez, J.E.; Luu, Q.; Emonts, M.; Maconochie, I.; Nijman, R.; Yeung, S. Role of Point-of-Care Tests in the Management of Febrile Children: A Qualitative Study of Hospital-Based Doctors and Nurses in England. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zama, D.; Leardini, D.; Biscardi, L.; Corsini, I.; Pierantoni, L.; Andreozzi, L.; Lanari, M. Activity of a Pediatric Emergency Department of a Tertiary Center in Bologna, Italy, during SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Pediatr. Rep. 2022, 14, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Period 1 | Period 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| GAS-RAD test | X | X |

| RSV-RAD test | X | X |

| DFAs | X | |

| SARS-CoV-2 antigenic test | X | |

| Multiplex PCR test | X | |

| CRP-POC | X | |

| COMBO test | X |

| Total Population n = 4882 | Period 1 n = 2181 | Period 2 n = 2701 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 2206 (45.2%) | 975 (44.7%) | 1231 (45.6%) | n.s. |

| Age [months], Median (IQR) | 32 (15–62) | 28 (14–53) | 37 (16–70) | <0.001 |

| Weight [kg], Median (IQR) | 14 (10–20) | 13 (10–18) | 14 (10.5–20) | <0.001 |

| Heart Rate [bpm], Mean (SD) | 137 (23.34) | 139 (23.52) | 135 (23.02) | <0.001 |

| SpO2 [%], Median (IQR) | 98 (97–99) | 98 (97–99) | 98 (97–99) | <0.001 |

| Body Temperature [°C], Mean (SD) | 37.7 (1.1) | 37.8 (1.1) | 37.6 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Fever duration [days], Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | <0.001 |

| Body temperature ≥ 38°C, n (%) | 4216 (86.4%) | 1856 (85.1%) | 2360 (87.4%) | 0.024 |

| Antibiotic prior to PED, n (%) | n.s. | |||

| -Amoxicillin | 348 (44%) | 150 (40.9%) | 198 (46.8%) | |

| -Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 227 (28.7%) | 106 (28.9%) | 121 (28.6%) | |

| -Cephalosporin | 106 (13.5%) | 54 (14.7%) | 52 (12.3%) | |

| -Macrolides | 109 (13.8%) | 57 (15.5%) | 52 (12.3%) | |

| Type of comorbidity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| -Heart disease | 56 (1.2%) | 25 (1.2%) | 31 (1.2%) | |

| -Neurological disease | 51 (1.0%) | 22 (1%) | 29 (1.1%) | |

| -Metabolic disease | 14 (0.3%) | 7 (0.3%) | 7 (0.3%) | |

| -Genetic syndrome | 44 (1%) | 8 (0.4%) | 36 (1.3%) | |

| -Kidney disease | 36 (0.7%) | 19 (0.9%) | 17 (0.6%) | |

| -Immunodeficiency | 5 (0.1%) | 2 (0.1%) | 3 (0.1%) | |

| -Oncological disease | 25 (0.5%) | 12 (0.6%) | 13 (0.5%) | |

| -Autoimmune disease | 4 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 3 (0.1%) | |

| -Lung disease | 150 (3.1%) | 43 (2%) | 107 (4%) | |

| -Prematurity | 54 (1.1%) | 19 (0.9%) | 35 (1.3%) | |

| -Endocrine disease | 10 (0.2%) | 6 (0.3%) | 4 (0.2%) | |

| -Febrile seizure | 116 (2.4%) | 60 (2.8%) | 56 (2.1%) | |

| Discharge diagnosis, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| -URTI | 2986 (61.2%) | 1253 (57.5%) | 1733 (64.2%) | |

| -Croup | 243 (5%) | 136 (6.2%) | 107 (4%) | |

| -Bronchitis | 940 (19.2%) | 469 (21.5%) | 471 (17.4%) | |

| -Bronchiolitis | 263 (5.4%) | 120 (5.5%) | 142 (5.3%) | |

| -Pneumonia | 450 (9.2%) | 203 (9.3%) | 247 (9.1%) |

| Total Population n = 4882 | Period 1 n = 2181 | Period 2 n = 2701 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic prescription, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| -new prescription ° | 1909 (39.1%) | 1053 (48.3%) | 855 (31.7%) | |

| -continue antibiotic | 424 (8.7%) | 183 (8.4%) | 241 (8.9%) | |

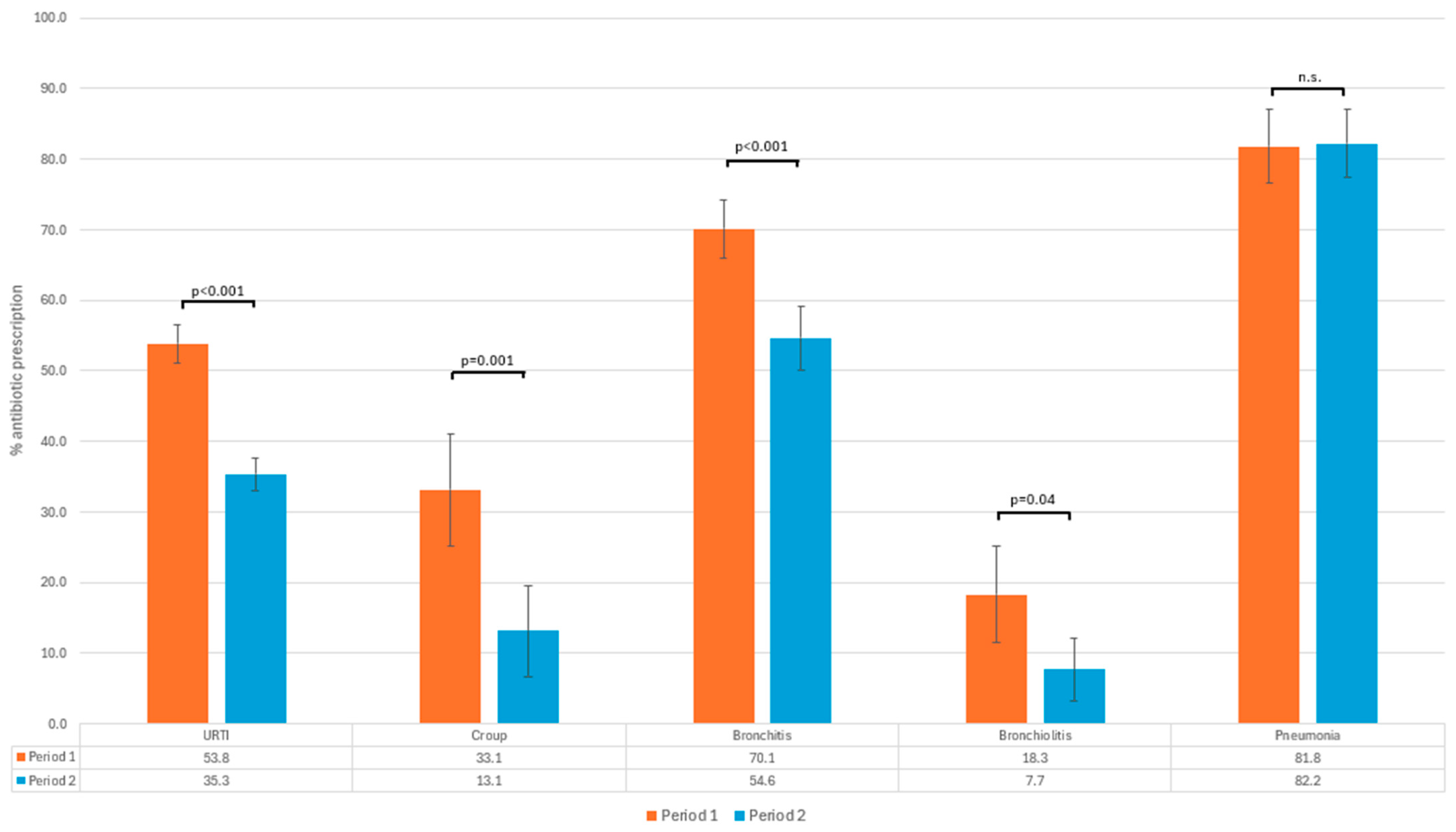

| Antibiotic prescription by diagnosis, n (% *): | <0.001 | |||

| -URTI | 1286 (43.1%) | 674 (53.8%) | 612 (35.3%) | |

| -Croup | 59 (24.3%) | 45 (33.1%) | 14 (13.1%) | |

| -Bronchitis | 586 (62.3%) | 329 (70.1%) | 257 (54.6%) | |

| -Bronchiolitis | 33 (12.5%) | 22 (18.3%) | 11 (7.7%) | |

| -Pneumonia | 369 (82%) | 166 (81.8%) | 203 (82.2%) | |

| Type of systemic antibiotic, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| -Amoxicillin | 1082 (46.4%) | 532 (43%) | 550 (50.2%) | |

| -Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 659 (28.3%) | 390 (31.6%) | 269 (24.5%) | |

| -Cephalosporin | 302 (12.9%) | 174 (14.1%) | 128 (11.7%) | |

| -Macrolides | 289 (12.4%) | 140 (11.3%) | 149 (13.6%) | |

| Length of therapy [days], Median (IQR) | 7 (6–7) | 7 (7–7) | 7 (6–7) | 0.004 |

| Laboratory blood tests performance, n (%) | 835 (17.1%) | 420 (19.3%) | 415 (15.4%) | <0.001 |

| CXRs performance, n (%) | 807 (16.5%) | 454 (20.8%) | 353 (13.1%) | <0.001 |

| LOS [minutes], Median (IQR) | 107 (54–193) | 97 (45–192) | 113 (60–194) | <0.001 |

| Type of discharge, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| -Home | 4235 (86.8%) | 1845 (84.6%) | 2390 (88.5%) | |

| -SSO | 289 (5.9%) | 159 (7.3%) | 130 (4.8%) | |

| -Hospitalization | 358 (7.3%) | 177 (8.1%) | 181 (6.7%) |

| Total Population n = 4882 | Period 1 n = 2181 | Period 2 n = 2701 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP-POC, n (%) | 447 (16.5%) | |||

| GAS-RAD, n (%) | 798 (16.3%) | 250 (11.5%) | 548 (20.3%) | <0.001 |

| RSV-RAD, n (%) | 339 (6.9%) | 115 (5.3%) | 224 (8.3%) | <0.001 |

| Rapid COMBO test, n (%) | 796 (29.5%) | |||

| Multiplex PCR test, n (%) | 783 (29%) | |||

| -Influenza A positive, n (%) | 269(34.4%) | |||

| -Influenza B positive, n (%) | 6 (0.8%) | |||

| -Parainfluenza positive, n (%) | 31 (4%) | |||

| -Rhinovirus positive, n (%) | 160 (20.4%) | |||

| -Metapneumovirus positive, n (%) | 43 (5.5%) | |||

| -Adenovirus positive, n (%) | 81 (10.3%) | |||

| -Respiratory Syncytial virus positive, n (%) | 149 (19%) |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | IC 95% | p | OR | IC 95% | p | |

| Period 1 | 1.91 | 1.71–2.14 | <0.001 | 2.01 | 1.73–2.33 | <0.001 |

| LOS | 1 | 1.00–1.00 | n.s. | |||

| Age (months) | 1.01 | 1.01–1.01 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.01–1.01 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 1.05 | 0.94–1.18 | n.s. | |||

| Days of fever | 1.21 | 1.18–1.25 | <0.001 | 1.19 | 1.16–1.24 | <0.001 |

| Body temperature ≥ 38 °C | 2.2 | 1.85–2.63 | <0.001 | 2.14 | 1.76–2.62 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity | 0.9 | 0.76–1.08 | n.s. | |||

| Laboratory blood tests | 0.88 | 0.76–1.02 | 0.093 | 0.66 | 0.56–0.79 | <0.001 |

| CXR | 2.47 | 2.11–2.90 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 0.83–1.28 | n.s. |

| POCTs (CRP + COMBO test) | 0.55 | 0.48–0.63 | <0.001 | 0.76 | 0.63–0.92 | 0.004 |

| Multiplex PCR test | 0.5 | 0.43–0.59 | <0.001 | 0.66 | 0.54–0.81 | <0.001 |

| Diagnosis (ref pneumonia): | 1.29 | 1.23–1.34 | <0.001 | |||

| -URTI | 0.17 | 0.12–0.21 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.13–0.24 | <0.001 |

| -croup | 0.07 | 0.05–0.1 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.05–0.11 | <0.001 |

| -bronchitis | 0.36 | 0.27–0.48 | <0.001 | 0.41 | 0.3–0.55 | <0.001 |

| -bronchiolitis | 0.03 | 0.02–0.05 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.03–0.09 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pierantoni, L.; Dondi, A.; Gabrielli, L.; Lasala, V.; Andreozzi, L.; Bruni, L.; Guida, F.; Battelli, E.; Piccirilli, G.; Corsini, I.; et al. The Use of Point-of-Care Tests and Multiplex PCR Tests in the Pediatric Emergency Department Reduces Antibiotic Prescription in Patients with Febrile Acute Respiratory Infections. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121284

Pierantoni L, Dondi A, Gabrielli L, Lasala V, Andreozzi L, Bruni L, Guida F, Battelli E, Piccirilli G, Corsini I, et al. The Use of Point-of-Care Tests and Multiplex PCR Tests in the Pediatric Emergency Department Reduces Antibiotic Prescription in Patients with Febrile Acute Respiratory Infections. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121284

Chicago/Turabian StylePierantoni, Luca, Arianna Dondi, Liliana Gabrielli, Valentina Lasala, Laura Andreozzi, Laura Bruni, Fiorentina Guida, Eleonora Battelli, Giulia Piccirilli, Ilaria Corsini, and et al. 2025. "The Use of Point-of-Care Tests and Multiplex PCR Tests in the Pediatric Emergency Department Reduces Antibiotic Prescription in Patients with Febrile Acute Respiratory Infections" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121284

APA StylePierantoni, L., Dondi, A., Gabrielli, L., Lasala, V., Andreozzi, L., Bruni, L., Guida, F., Battelli, E., Piccirilli, G., Corsini, I., Lazzarotto, T., Lanari, M., & Zama, D. (2025). The Use of Point-of-Care Tests and Multiplex PCR Tests in the Pediatric Emergency Department Reduces Antibiotic Prescription in Patients with Febrile Acute Respiratory Infections. Pathogens, 14(12), 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121284