Systemic Inflammatory Indices (SII and SIRI) in 30-Day Mortality Risk Stratification for Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Study Alongside CURB-65 and PSI

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

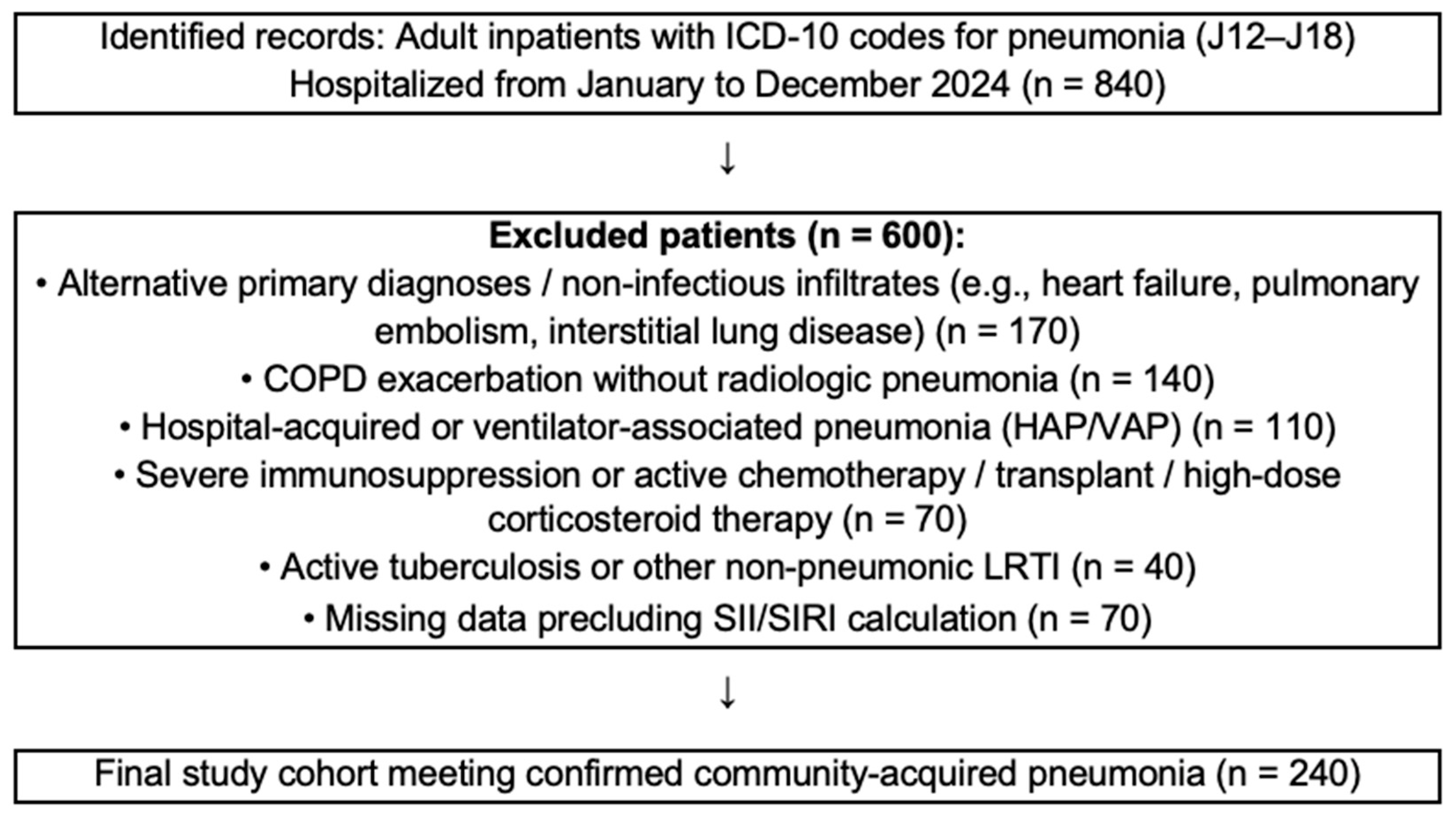

2.2. Study Population

- (1)

- Age < 18 years;

- (2)

- Hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated pneumonia (HAP/VAP);

- (3)

- Severe immunosuppression or active chemotherapy, solid organ transplantation, or chronic corticosteroid therapy (>20 mg/day for ≥2 weeks);

- (4)

- Active pulmonary tuberculosis or other non-pneumonic lower respiratory tract infection;

- (5)

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation without radiologic pneumonia;

- (6)

- Alternative primary diagnoses or non-infectious infiltrates (e.g., heart failure, pulmonary embolism, interstitial lung disease);

- (7)

- Missing data precluding the calculation of SII/SIRI.

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Demographic, Clinical, and Laboratory Characteristics

3.2. Baseline Correlation Analysis of Inflammatory and Clinical Parameters

3.3. Logistic Regression Analysis for Predictors of 30-Day Mortality

3.4. Discriminative Performance of Predictive Models (ROC Analysis)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- File, T.M.; Ramirez, J.A. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metlay, J.P.; Waterer, G.W.; Long, A.C.; Anzueto, A.; Brozek, J.; Crothers, K.; Cooley, L.A.; Dean, N.C.; Fine, M.J.; Flanders, S.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e45–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.S.; van der Eerden, M.M.; Laing, R.; Boersma, W.G.; Karalus, N.; I Town, G.; A Lewis, S.; Macfarlane, J.T. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: An international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003, 58, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, M.J.; Auble, T.E.; Yealy, D.M.; Hanusa, B.H.; Weissfeld, L.A.; Singer, D.E.; Coley, C.M.; Marrie, T.J.; Kapoor, W.N. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Zhuang, L.; Shen, Y.; Geng, Y.; Yu, S.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Meng, Z.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy. Cancer 2016, 122, 2158–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Yang, X.-R.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.-F.; Sun, C.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.-M.; Qiu, S.-J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 6212–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, B.; Yetkin, N.A.; Rabahoğlu, B.; Tutar, N.; Gülmez, I. Assessment of Mortality Risk in Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Role of Novel Inflammatory Biomarkers. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2025, 39, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, E.; Gokcen, H.; Demir, A.; Yildirim, B. Comparison of inflammation markers with prediction scores in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2021, 122, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, W. Combined Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index-Prognostic Nutritional Index Score in Evaluating the Prognosis of Patients with Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 7105–7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corica, B.; Tartaglia, F.; D’Amico, T.; Romiti, G.F.; Cangemi, R. Sex and gender differences in community-acquired pneumonia. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 1575–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, M.J.; A Smith, M.; A Carson, C.; Mutha, S.S.; Sankey, S.S.; A Weissfeld, L.; Kapoor, W.N. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis. JAMA 1996, 275, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Mourtzoukou, E.G.; Vardakas, K.Z. Sex differences in the incidence and severity of respiratory tract infections. Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 1845–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Miguel-Díez, J.; Jiménez-García, R.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Jiménez-Trujillo, I.; de Miguel-Yanes, J.M.; Méndez-Bailón, M.; López-De-Andrés, A. Trends in hospitalizations for community-acquired pneumonia in Spain: 2004 to 2013. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 40, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrani, P.; Arnold, F.W.; Bordon, J.; Furmanek, S.; Luna, C.M.; Cavallazzi, R.; Ramirez, J. Incidence and Mortality of Adults Hospitalized with Community-Acquired Pneumonia According to Clinical Course. Chest 2020, 157, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.D.; Burroughs-Ray, D.C.; Summers, N.A. Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: 2019 American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America Update on Community-Acquired Pneumonia. J. Hosp. Med. 2020, 15, 743–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederman, M.S.; Torres, A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespanhol, V.; Bárbara, C. Pneumonia mortality, comorbidities matter? Pulmonology 2020, 26, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, C.M.; Palma, I.; Niederman, M.S.; Membriani, E.; Giovini, V.; Wiemken, T.L.; Peyrani, P.; Ramirez, J. The Impact of Age and Comorbidities on the Mortality of Patients of Different Age Groups Admitted with Community-acquired Pneumonia. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A.; Ishida, T.; Tokumasu, H.; Washio, Y.; Yamazaki, A.; Ito, Y.; Tachibana, H. Prognostic factors in hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia: A retrospective study of a prospective observational cohort. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Pan, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, J. Clinical characteristics, laboratory outcome characteristics, comorbidities, and complications of related COVID-19 deceased: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennamadhavuni, A.; Abushahin, L.; Jin, N.; Presley, C.J.; Manne, A. Risk Factors and Biomarkers for Immune-Related Adverse Events: A Practical Guide to Identifying High-Risk Patients and Rechallenging Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 779691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzinska, F.S.; Brodlie, M.; Scholefield, B.R.; Jackson, T.; Scott, A.; Thickett, D.R.; Sapey, E. Neutrophils in community-acquired pneumonia: Parallels in dysfunction at the extremes of age. Thorax 2020, 75, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Guan, S.; Kong, X.; Ji, W.; Du, C.; Jia, M.; Wang, H. Predictors of mortality in severe pneumonia patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Su, L.; Guan, W.; Xiao, K.; Xie, L. Prognostic value of procalcitonin in pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respirology 2016, 21, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Mao, S.; Liu, X.; Zhu, C. Association of systemic inflammation response index with all-cause mortality as well as cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1363949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Bian, T.; Shen, Y.; Huang, Z. Association between admission systemic immune-inflammation index and mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: A retrospective cohort study based on MIMIC-IV database. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 3641–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Xia, C.; Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Systemic Immune Inflammation Index (SII), System Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) and Risk of All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Mortality: A 20-Year Follow-Up Cohort Study of 42,875 US Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Overall (n = 240) | Survivors (n = 203) | Non-Survivors (n = 37) | p-Value (Unadjusted) | p (Adjusted) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 75.50 (21–95) | 72.02 ± 14.41 | 76.54 ± 11.94 | 0.104 | - |

| Male sex, n (%) | 146 (60.8%) | 119 (58.6%) | 27 (73%) | 0.070 | - |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 140 (58.3%) | 116 (57.1%) | 24 (64.9%) | 0.245 | 0.987 |

| Hospitalization within past 90 days, n (%) | 51 (21.3%) | 38 (18.7%) | 13 (35.1%) | 0.025 | 0.066 |

| Recent antibiotic use, n (%) | 93 (38.8%) | 72 (35.5%) | 21 (56.8%) | 0.013 | 0.019 |

| Any comorbidity, n (%) | 207 (86.3%) | 172 (84.7%) | 35 (94.6%) | 0.082 | 0.317 |

| COPD, n (%) | 71 (29.6%) | 58 (28.6%) | 13 (35.1%) | 0.268 | 0.476 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 57 (23.8%) | 49 (24.1%) | 8 (21.6%) | 0.462 | 0.804 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 94 (39.2%) | 79 (38.9%) | 15 (40.5%) | 0.318 | 0.577 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 63 (26.3%) | 55 (27.1%) | 8 (21.6%) | 0.495 | 0.593 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 59 (24.6%) | 46 (22.7%) | 13 (35.1%) | 0.082 | 0.256 |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 30 (12.5%) | 18 (8.9%) | 12 (34.4%) | <0.001 | - |

| PSI score, mean ± SD | 113.15 ± 35.07 | 107.38 ± 31.50 | 143.84 ± 37.50 | <0.001 | - |

| CURB-65 ≥ 3, n (%) | 33 (13.8%) | 20 (9.9%) | 13 (%35.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 11.81 [0.64–43.48] | 11.82 [1.06–43.48] | 11.80 [0.64–40.10] | 0.366 | 0.206 |

| Neutrophil (×109/L) | 9.975 [0.47–42.06] | 9.90 [0.57–42.06] | 10.17 [0.47–38.30] | 0.204 | 0.154 |

| Lymphocyte (×109/L) | 0.89 [0.04–6.60] | 0.91 [0.04–6.60] | 0.73 [0.14–2.67] | 0.013 | 0.067 |

| Monocyte (×109/L) | 0.57 [0–3.30] | 0.57 [0.01–3.30] | 0.50 [0–2.45] | 0.550 | 0.619 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 238.50 [30–1275] | 238 [30–697] | 242 [109–1275] | 0.685 | 0.354 |

| SII (×103) | 2.61 [0–56.90] | 2.57 [0–56.90] | 3.01 [0.81–56.37] | 0.043 | 0.063 |

| SIRI | 5.49 [0–83.75] | 5.32 [0.06–83.75] | 7.66 [0–64.88] | 0.072 | 0.046 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 135 [3.11–417] | 129 [4.41–417] | 169.31 ± 100.69 | 0.157 | 0.094 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.40 [0.01–100] | 0.3 [0.01–100] | 1.16 [0.03–70] | 0.014 | 0.235 |

| PSI Score | CURB-65 | SII | SIRI | CRP | Procalcitonin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSI Score | 1.000 | 0.636 | 0.199 | 0.132 | 0.038 | 0.158 |

| CURB-65 | 1.000 | 0.216 | 0.183 | 0.125 | 0.245 | |

| SII | 1.000 | 0.711 | 0.275 | 0.209 | ||

| SIRI | 1.000 | 0.347 | 0.278 | |||

| CRP | 1.000 | 0.451 | ||||

| Procalcitonin | 1.000 |

| Variable/Model | B | SE | Wald | OR (Exp B) | 95% CI for OR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 CURB-65 | 1.058 | 0.263 | 16.125 | 2.879 | 1.718–4.825 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 PSI | 0.035 | 0.007 | 28.233 | 1.036 | 1.022–1.049 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 SII | 0.453 | 0.181 | 6.257 | 1.574 | 1.103–2.245 | 0.012 |

| Model 4 SIRI | 0.367 | 0.170 | 4.685 | 1.444 | 1.035–2.013 | 0.030 |

| Model 5 CRP | 0.003 | 0.002 | 2.421 | 1.003 | 0.999–1.007 | 0.120 |

| Model 6 Procalcitonin | 0.015 | 0.011 | 1.919 | 1.015 | 0.994–1.038 | 0.166 |

| Model 7 CURB-65 SII | 1.024 0.000 | 0.266 0.000 | 14.846 3.384 | 2.783 1.000 | 1.654–4.685 1.000–1.000 | <0.001 0.066 |

| Model-8 CURB-65 SIRI | 1.041 0.025 | 0.268 0.013 | 15.084 3.773 | 2.831 1.026 | 1.674–4.786 1.000–1.052 | <0.001 0.052 |

| Model-9 PSI SII | 0.034 0.000 | 0.007 0.000 | 26.242 2.066 | 1.035 1.000 | 1.021–1.048 1.000–1.000 | <0.001 0.151 |

| Model-10 PSI SIRI | 0.035 0.025 | 0.007 0.014 | 26.855 3.415 | 1.035 1.026 | 1.022–1.049 0.998–1.054 | <0.001 0.065 |

| AUC (95% CI) | SE | p (vs. 0.5) | ΔAUC (vs. Base Model) | 95% CI for ΔAUC | p (DeLong) | Optimal Cut-Off | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP | 0.569 (0.467–0.671) | 0.052 | 0.187 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| PCT | 0.627 (0.531–0.723) | 0.049 | 0.010 | >1.16 | 51.4 | 72.7 | |||

| SII | 0.605 (0.540–0.667) | 0.053 | 0.047 | - | - | - | >8.53 | 43.2 | 76.9 |

| SIRI | 0.609 (0.544–0.672) | 0.054 | 0.042 | - | - | - | >1.68 | 69.4 | 50.3 |

| CURB-65 | 0.684 (0.621–0.742) | 0.043 | <0.001 | - | - | - | >2 | 35.1 | 90.2 |

| CURB-65 + SII | 0.723 (0.662–0.779) | 0.046 | <0.001 | 0.039 | −0.007–0.085 | 0.098 | |||

| CURB-65 + SIRI | 0.727 (0.665–0.782) | 0.048 | <0.001 | 0.043 | −0.007–0.091 | 0.091 | |||

| PSI | 0.768 (0.709–0.820) | 0.046 | <0.001 | - | - | - | >140 | 62.2 | 84.7 |

| PSI + SII | 0.774 (0.715–0.825) | 0.045 | <0.001 | 0.006 | −0.012–0.023 | 0.533 | |||

| PSI + SIRI | 0.776 (0.718–0.827) | 0.046 | <0.001 | 0.008 | −0.017–0.033 | 0.543 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Terzi, O.E.; Afşar, G.Ç.; Çetin, N.; Dülger, S. Systemic Inflammatory Indices (SII and SIRI) in 30-Day Mortality Risk Stratification for Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Study Alongside CURB-65 and PSI. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121235

Terzi OE, Afşar GÇ, Çetin N, Dülger S. Systemic Inflammatory Indices (SII and SIRI) in 30-Day Mortality Risk Stratification for Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Study Alongside CURB-65 and PSI. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121235

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerzi, Orkun Eray, Gülgün Çetintaş Afşar, Nazlı Çetin, and Seyhan Dülger. 2025. "Systemic Inflammatory Indices (SII and SIRI) in 30-Day Mortality Risk Stratification for Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Study Alongside CURB-65 and PSI" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121235

APA StyleTerzi, O. E., Afşar, G. Ç., Çetin, N., & Dülger, S. (2025). Systemic Inflammatory Indices (SII and SIRI) in 30-Day Mortality Risk Stratification for Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Study Alongside CURB-65 and PSI. Pathogens, 14(12), 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121235