Interspecies Transmission of Animal Rotaviruses to Humans: Reassortment-Driven Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Two Key Questions Regarding Interspecies Rotavirus Transmission

3. What Is a Strain of Rotavirus and How to Define It?

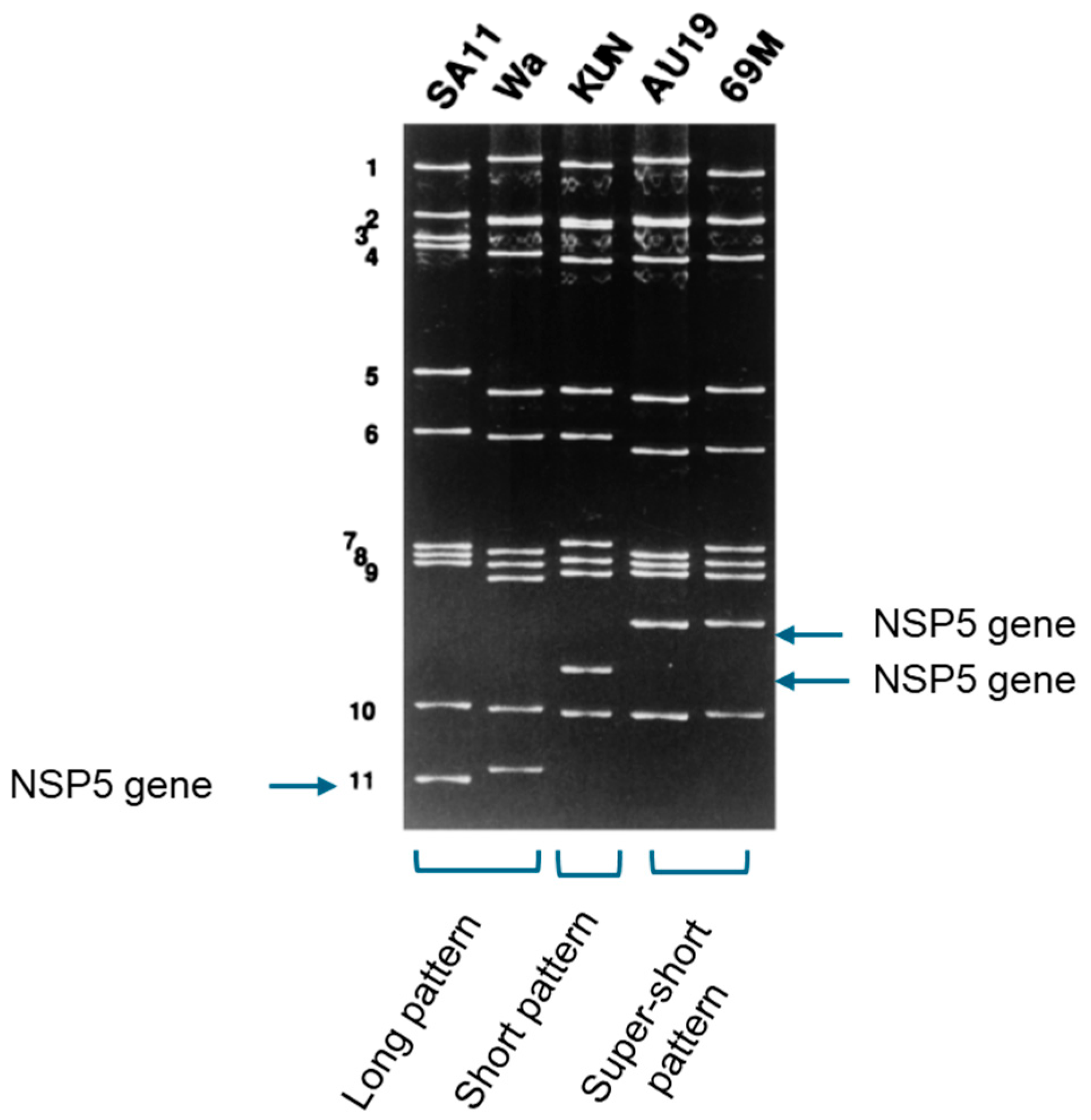

4. Advancement of Analysing the Whole Genome: RNA–RNA Hybridisation

5. Further Advancement by Whole Genome Sequencing and Phylogeny

5.1. Defining a Genotype and Genotype Constellation

5.2. Classification Within a Genotype: Sub-Genotype Phylogeny

6. From Spillover Event to Emerging Epidemic

6.1. Need for Timely Surveillance

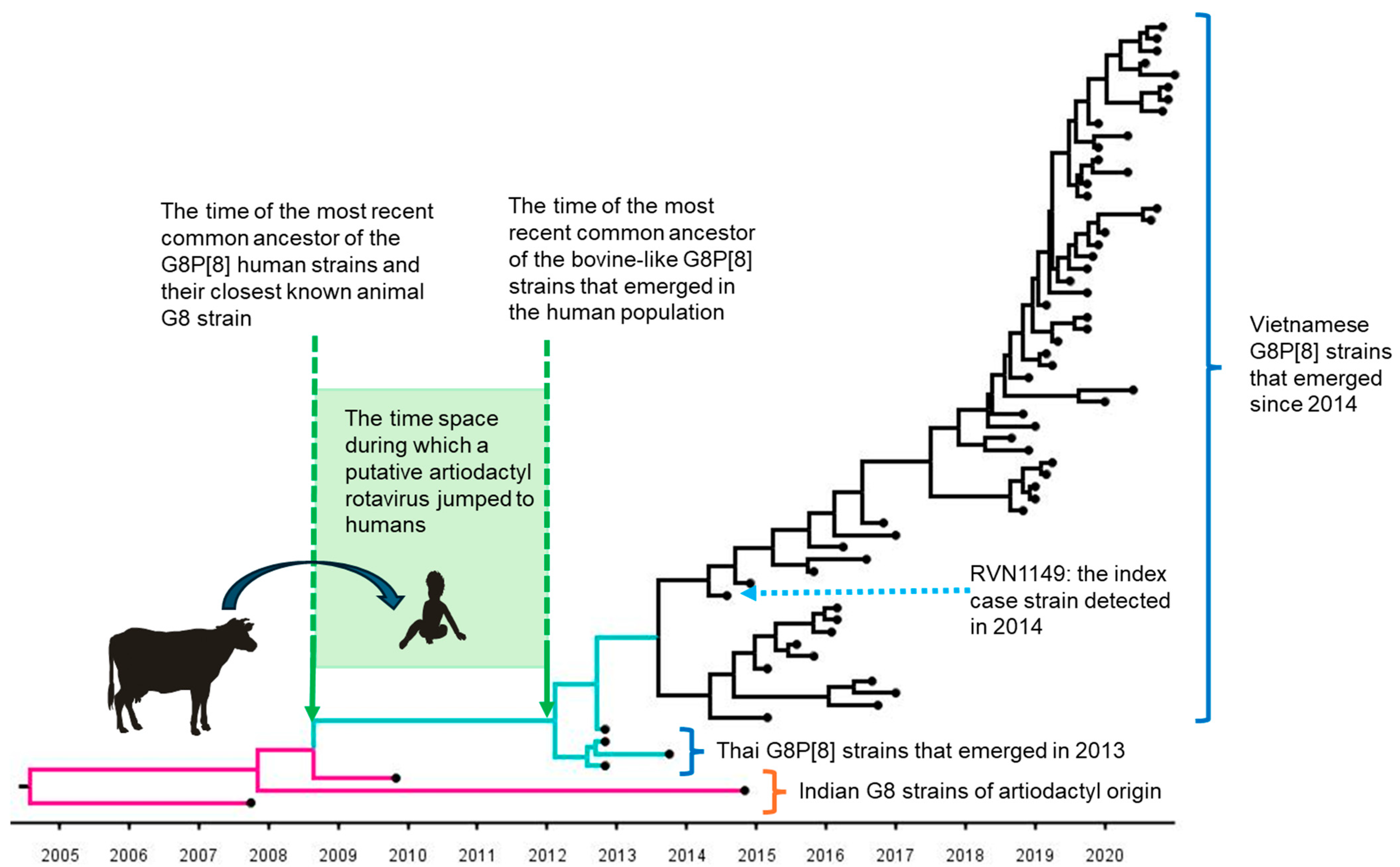

6.2. Bovine-like G8P[8] Strains That Emerged in VIETNAM in 2014

6.2.1. Observations in Vietnam

6.2.2. Observations in Nearby Countries

6.2.3. Estimated Time of Jumping from an Artiodactyla to Humans

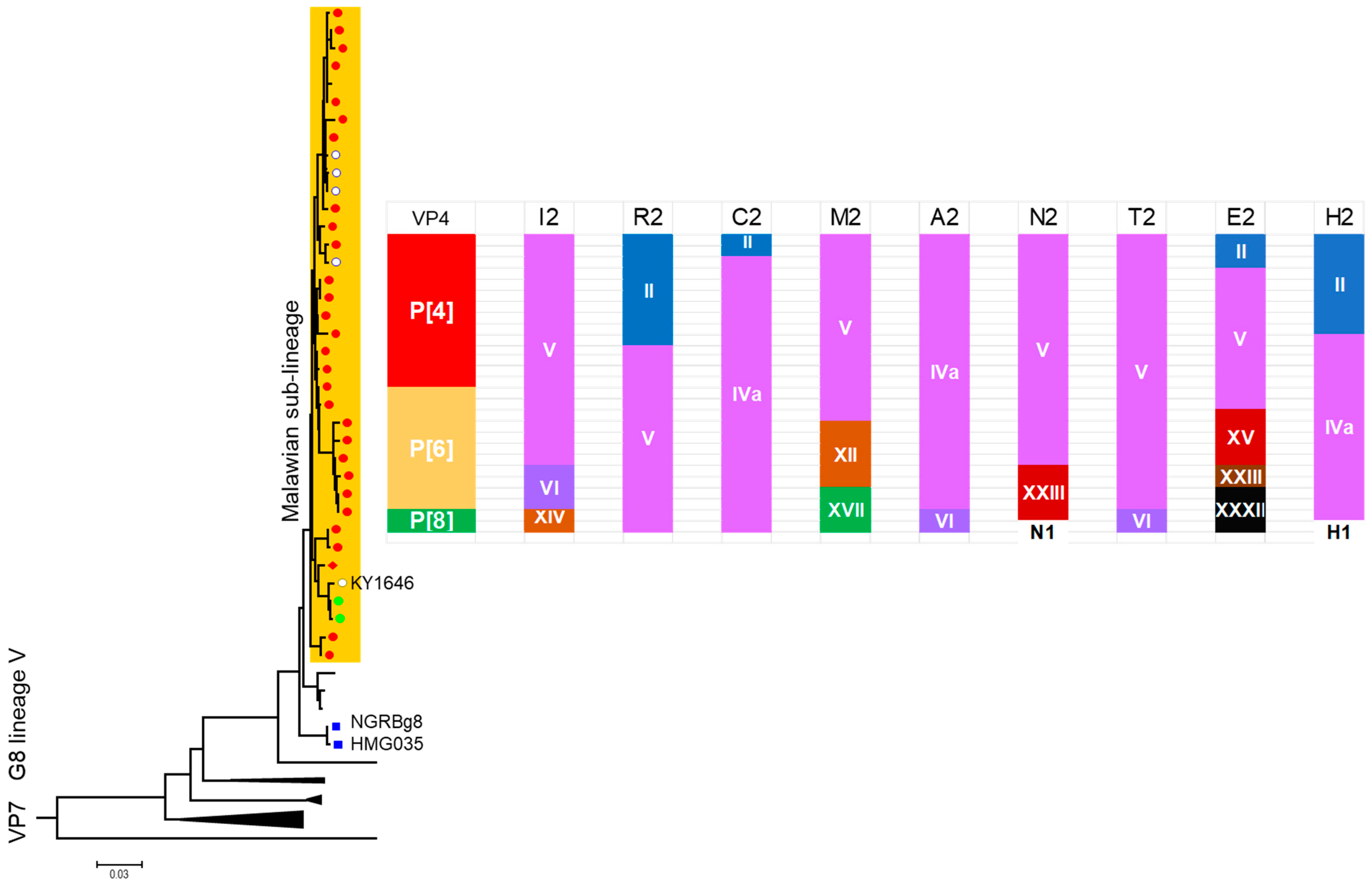

7. Do G8 Strains Endemic in Africa Reflect Repeated Introductions of Bovine-to-Human Interspecies Transmission?

7.1. Unexpectedly High Prevalence of G8 in Africa

7.2. Evolution of Malawi G8 During 10-Year Surveillance

7.3. Incidental Observations of an Experimental Human-to-Animal Transmission

7.4. G8 Strains That Ended in Spillover Events Without Inheritable Consequences

8. What Factors Enable Animal Rotavirus Strains to Adapt to the Human Host?

8.1. The Role of the VP4 Spike Protein in the Initial Binding to the Heterologous Host Cell

8.2. The Role of the DS-1-like Backbone Genes in Sustained Transmission

8.3. Bovine-like G8P[8] Strains That Failed to Spread Despite the DS-1-like Backbone Genes

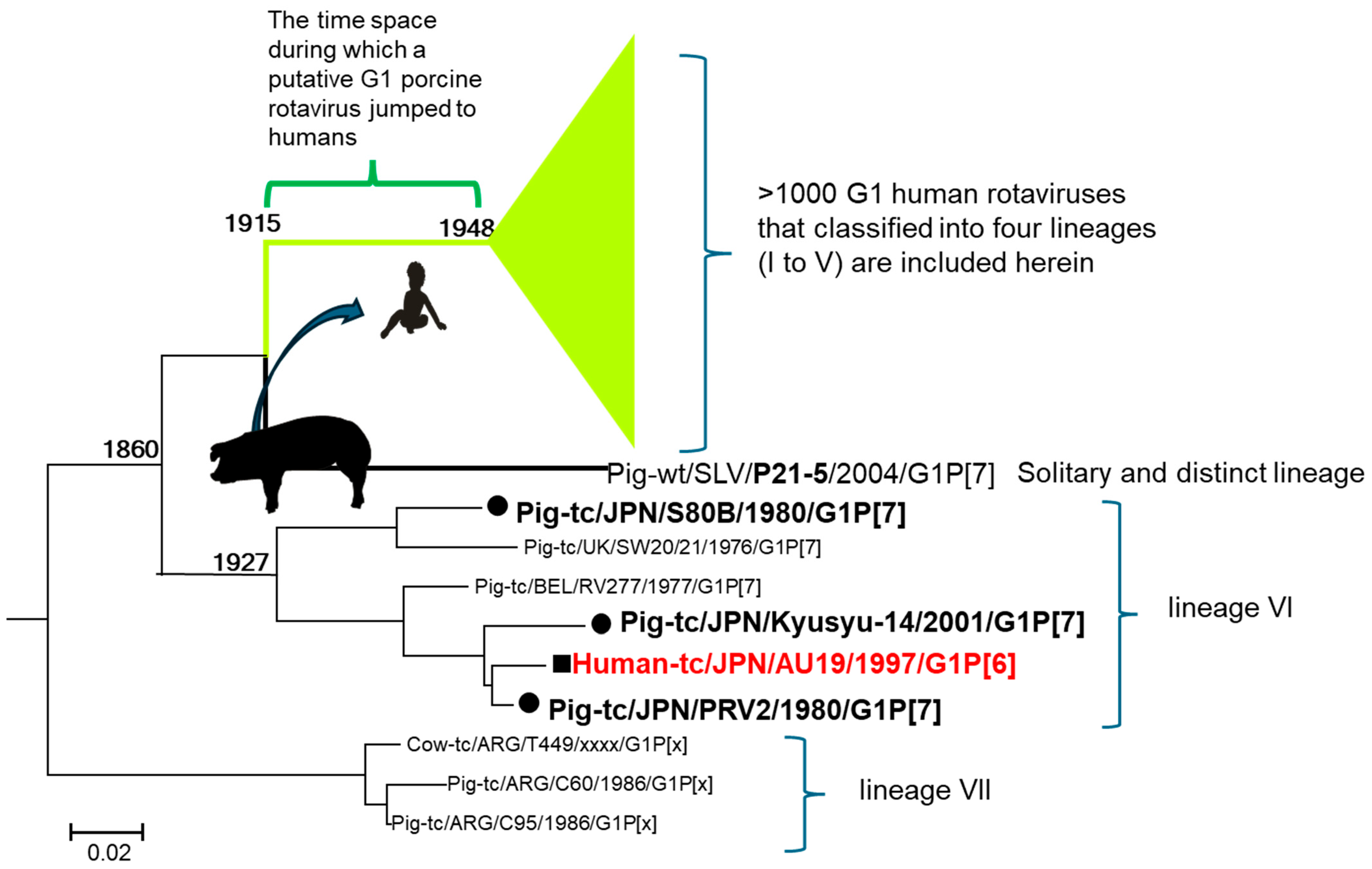

9. Re-Evaluation of the Phylogenetic Tree Revealed the Origin of Contemporary G1 Human Rotaviruses

9.1. A Super-Short Strain Was Found

9.2. The Strain Has a New P Serotype

9.3. Analysis by Whole Genome Sequencing

9.4. The Timing of the Introduction of the G1 VP7 to Humans

9.5. The Puzzle Was Solved

10. Discussion

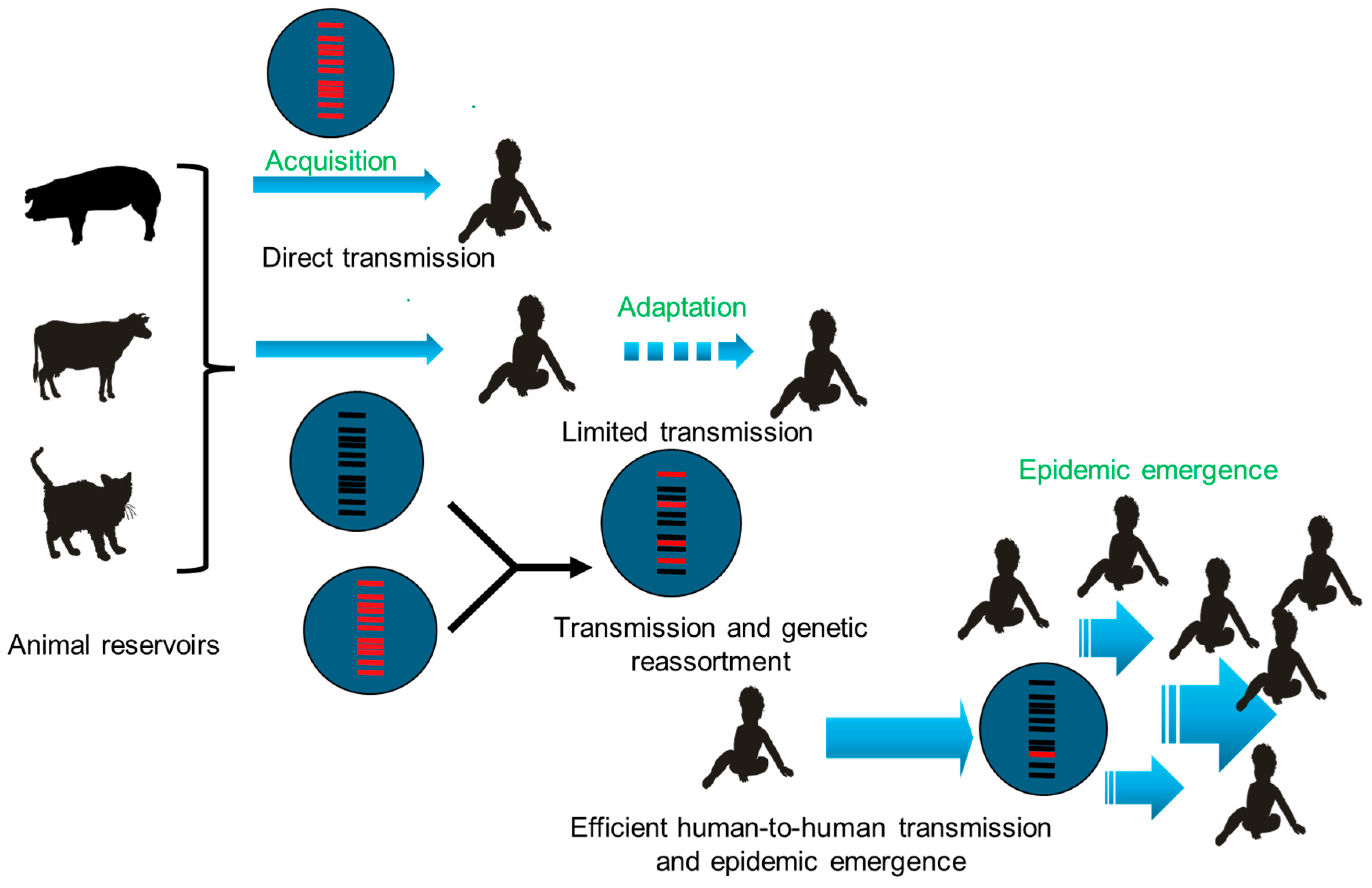

10.1. From Spillovers to Epidemics

- Acquisition of the ability to infect a new host’s cells.

- Adaptative mutations to the novel host, facilitating transmission between individuals.

- Epidemic emergence in the host population.

10.1.1. Acquisition

10.1.2. Adaptative Mutations

10.1.3. Epidemic Emergence

11. Future Directions

11.1. Molecular Mechanisms Enabling Successful Spread in Humans

11.2. Integrated Genomic Surveillance at the Animal-Human Interface

11.3. The Role of Rotavirus Genome Diversification in Vaccine Selective Pressure

11.4. Accelerated Viral Evolution Following Interspecies Transmission

11.5. Virulence of Animal-Derived Rotaviruses

11.6. Definition of Animal-Derived Genes

11.7. The Critical Role of Mixed Infection and Deep Sequencing

12. Concluding Remarks and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VP | Viral protein |

| NSP | Non-structural protein |

| PAGE | Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| HBGA | Histo-Blood Group Antigen |

References

- Matthijnssens, J.; Attoui, H.; Bányai, K.; Brussaard, C.P.D.; Danthi, P.; Del Vas, M.; Dermody, T.S.; Duncan, R.; Fāng, Q.; Johne, R.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Sedoreoviridae 2022. J. Gen. Virol. 2022, 103, 001782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz Alarcón, R.G.; Salvatierra, K.; Gómez Quintero, E.; Liotta, D.J.; Parreño, V.; Miño, S.O. Complete Genome Classification System of Rotavirus alphagastroenteritidis: An Updated Analysis. Viruses 2025, 17, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S.E.; Ding, S.; Greenberg, H.B.; Estes, M.K. Rotaviruses. In Field’s Virology, Volume 3: RNA Viruses, 7th ed.; Howley, P.M., Knipe, D.M., Damania, B.A., Cohen, J.I., Whelan, S.P.J., Freed, E.O., Eds.; Wolters Kluver: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 362–799. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T. Interspecies transmission of rotaviruses studied from the perspective of genogroup. Microbiol. Immunol. 1993, 37, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T. Genomic relationships among rotaviruses recovered from various animal species as revealed by RNA-RNA hybridization assays. Res. Vet. Sci. 2002, 73, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombo, E.A. Genetic analysis of Group A rotaviruses: Evidence for interspecies transmission of rotavirus genes. Virus Genes 2002, 24, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martella, V.; Bányai, K.; Matthijnssens, J.; Buonavoglia, C.; Ciarlet, M. Zoonotic aspects of rotaviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 140, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Alarcón, R.G.; Liotta, D.J.; Miño, S. Zoonotic RVA: State of the Art and Distribution in the Animal World. Viruses 2022, 14, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, Y.H.; Nakagomi, T.; Aboudy, Y.; Silberstein, I.; Behar-Novat, E.; Nakagomi, O.; Shulman, L.M. Identification by full-genome analysis of a bovine rotavirus transmitted directly to and causing diarrhea in a human child. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, H.B.; Vo, P.T.; Jones, R. Cultivation and characterization of three strains of murine rotavirus. J. Virol. 1986, 57, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broome, R.L.; Vo, P.T.; Ward, R.L.; Clark, H.F.; Greenberg, H.B. Murine rotavirus genes encoding outer capsid proteins VP4 and VP7 are not major determinants of host range restriction and virulence. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 2448–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, N.; Burns, J.W.; Bracy, L.; Greenberg, H.B. Comparison of mucosal and systemic humoral immune responses and subsequent protection in mice orally inoculated with a homologous or a heterologous rotavirus. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 7766–7773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, E. Driving force in evolution: An analysis of natural selection. In The Evolutionary Biology of Viruses; Morse, S.S., Ed.; Raven Press, Ltd.: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, R.T.; Calderón, E.; González, N.; Salomon, A.; Martuscelli, A.; Romero, P. Presence of two distinct types of rotavirus in infants and young children hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in Mexico City, 1977. J. Infect. Dis. 1979, 139, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, I.H. Development of rotavirus molecular epidemiology: Electropherotyping. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 1996, 12, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Eichhorn, W.; Krauß, M.; Bachmann, P.A.; Mayr, A. Vorkommen und Verbreitung atypischer Rotaviren bei Kälbern in Deutschland. Tierärztl. Umschau 1985, 40, 435–436. [Google Scholar]

- Brüssow, H.; Nakagomi, O.; Gerna, G.; Eichhorn, W. Isolation of an avianlike group A rotavirus from a calf with diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Sugiyama, M.; Takayama, M.; Atoji, Y.; Masegi, T.; Minamoto, N. Avian-to-mammal transmission of an avian rotavirus: Analysis of its pathogenicity in a heterologous mouse model. Virology 2001, 288, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Borgan, M.A.; Takayama, M.; Ito, N.; Sugiyama, M.; Minamoto, N. Roles of outer capsid proteins as determinants of pathogenicity and host range restriction of avian rotaviruses in a suckling mouse model. Virology 2003, 316, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, J.; Perez, I.; White, L.; Perez, M.; Kalica, A.R.; Marquina, R.; Wyatt, R.G.; Kapikian, A.Z.; Chanock, R.M. Genetic relatedness among human rotaviruses as determined by RNA hybridization. Infect. Immun. 1982, 37, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; Hoshino, Y.; Boeggeman, E.; Purcell, R.; Chanock, R.M.; Kapikian, A.Z. Genetic relatedness among animal rotaviruses. Arch. Virol. 1986, 87, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; Midthun, K.; Hoshino, Y.; Green, K.; Gorziglia, M.; Kapikian, A.Z.; Chanock, R.M. Conservation of the fourth gene among rotaviruses recovered from asymptomatic newborn infants and its possible role in attenuation. J. Virol. 1986, 60, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, T.; Nakagomi, O. RNA-RNA hybridization identifies a human rotavirus that is genetically related to feline rotavirus. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T.; Akatani, K.; Ikegami, N. Identification of rotavirus genogroups by RNA-RNA hybridization. Mol. Cell. Probes 1989, 3, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T. Molecular epidemiology of human rotaviruses: Genogrouping by RNA-RNA hybridization. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 1996, 12, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, O.; Oyamada, H.; Nakagomi, T. Use of alkaline northern blot hybridization for the identification of genetic relatedness of the fourth gene of rotaviruses. Mol. Cell. Probes 1989, 3, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T. Genetic diversity and similarity among mammalian rotaviruses in relation to interspecies transmission of rotavirus. Arch. Virol. 1991, 120, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, T.; Nakagomi, O. Human rotavirus HCR3 possesses a genomic RNA constellation indistinguishable from that of feline and canine rotaviruses. Arch. Virol. 2000, 145, 2403–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagomi, O.; Kaga, E.; Gerna, G.; Sarasini, A.; Nakagomi, T. Subgroup I serotype 3 human rotavirus strains with long RNA pattern as a result of naturally occurring reassortment between members of the bovine and AU-1 genogroups. Arch. Virol. 1992, 126, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagomi, O.; Kaga, E.; Nakagomi, T. Human rotavirus strain with unique VP4 neutralization epitopes as a result of natural reassortment between members of the AU-1 and Wa genogroups. Arch. Virol. 1992, 127, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, S.J.; Greenberg, H.B.; Ward, R.L.; Nakagomi, O.; Burns, J.W.; Vo, P.T.; Pax, K.A.; Das, M.; Gowda, K.; Rao, C.D. Serotypic and genotypic characterization of human serotype 10 rotaviruses from asymptomatic neonates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K.; Gentsch, J.R.; Hoshino, Y.; Ishida, S.; Nakagomi, O.; Bhan, M.K.; Kumar, R.; Glass, R.I. Characterization of the G serotype and genogroup of New Delhi newborn rotavirus strain 116E. Virology 1993, 197, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizuka, M.; Kaga, E.; Chiba, M.; Masamune, O.; Gerna, G.; Nakagomi, O. Serotype G6 human rotavirus sharing a conserved genetic constellation with natural reassortants between members of the bovine and AU-1 genogroups. Arch. Virol. 1994, 135, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, N.A.; Gentsch, J.R.; Kirkwood, C.D.; Gondwe, J.S.; Dove, W.; Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T.; Hoshino, Y.; Bresee, J.S.; Glass, R.I.; et al. Molecular and serologic characterization of novel serotype G8 human rotavirus strains detected in Blantyre, Malawi. Virology 2000, 274, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baele, G.; Ji, X.; Hassler, G.W.; McCrone, J.T.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Holbrook, A.J.; Lemey, P.; Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A.; et al. BEAST X for Bayesian phylogenetic, phylogeographic and phylodynamic inference. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; Heiman, E.; Arijs, I.; Delbeke, T.; McDonald, S.M.; Palombo, E.A.; Iturriza-Gomara, M.; Maes, P.; Patton, J.T.; et al. Full genome-based classification of rotaviruses reveals a common origin between human Wa-Like and porcine rotavirus strains and human DS-1-like and bovine rotavirus strains. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 3204–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; Rahman, M.; Attoui, H.; Bányai, K.; Estes, M.K.; Gentsch, J.R.; Iturriza-Gómara, M.; Kirkwood, C.D.; Martella, V.; et al. Recommendations for the classification of group A rotaviruses using all 11 genomic RNA segments. Arch. Virol. 2008, 153, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, E.M.; McDonald, S.M.; Barro, M.; Taraporewala, Z.F.; Bar-Magen, T.; Patton, J.T. Group A human rotavirus genomics: Evidence that gene constellations are influenced by viral protein interactions. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11106–11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbemabiese, C.A.; Nakagomi, T.; Damanka, S.A.; Dennis, F.E.; Lartey, B.L.; Armah, G.E.; Nakagomi, O. Sub-genotype phylogeny of the non-G, non-P genes of genotype 2 Rotavirus A strains. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoa-Tran, T.N.; Nakagomi, T.; Vu, H.M.; Do, L.P.; Gauchan, P.; Agbemabiese, C.A.; Ngyen, T.T.; Thanh, N.T.; Dang, A.D.; Nakagomi, O. Abrupt emergence and predominance in Vietnam of rotavirus A strains possessing a bovine-like G8 on a DS-1-like background. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowley, D.; Donato, C.M.; Roczo-Farkas, S.; Kirkwood, C.D. Emergence of a novel equine-like G3P[8] inter-genogroup reassortant rotavirus strain associated with gastroenteritis in Australian children. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoto, S.; Tacharoenmuang, R.; Guntapong, R.; Ide, T.; Tsuji, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Tharmaphornpilas, P.; Sangkitporn, S.; Taniguchi, K. Reassortment of Human and Animal Rotavirus Gene Segments in Emerging DS-1-Like G1P[8] Rotavirus Strains. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoa-Tran, T.N.; Nakagomi, T.; Vu, H.M.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Dao, A.T.H.; Nguyen, A.T.; Bines, J.E.; Thomas, S.; Grabovac, V.; Kataoka-Nakamura, C.; et al. Evolution of DS-1-like G8P[8] rotavirus A strains from Vietnamese children with acute gastroenteritis (2014–21): Adaptation and loss of animal rotavirus-derived genes during human-to-human spread. Virus Evol. 2024, 10, veae045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacharoenmuang, R.; Komoto, S.; Guntapong, R.; Ide, T.; Sinchai, P.; Upachai, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; Tharmaphornpilas, P.; Sangkitporn, S.; Taniguchi, K. Full Genome Characterization of Novel DS-1-Like G8P[8] Rotavirus Strains that Have Emerged in Thailand: Reassortment of Bovine and Human Rotavirus Gene Segments in Emerging DS-1-Like Intergenogroup Reassortant Strains. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-It, W.; Chanta, C.; Ushijima, H. Predominance of DS-1-like G8P[8] rotavirus reassortant strains in children hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in Thailand, 2018–2020. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Chen, L.N.; Wang, S.M.; Zhou, H.L.; Qiu, C.; Jiang, B.; Qiu, T.Y.; Chen, S.L.; von Seidlein, L.; Wang, X.Y. Genetic characterization of two G8P[8] rotavirus strains isolated in Guangzhou, China, in 2020/21: Evidence of genome reassortment. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, R.S.; França, Y.; Viana, E.; de Azevedo, L.S.; Guiducci, R.; de Lima Neto, D.F.; da Costa, A.C.; Luchs, A. Genomic Constellation of Human Rotavirus G8 Strains in Brazil over a 13-Year Period: Detection of the Novel Bovine-like G8P[8] Strains with the DS-1-like Backbone. Viruses 2023, 15, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bányai, K.; Papp, H.; Dandár, E.; Molnár, P.; Mihály, I.; Van Ranst, M.; Martella, V.; Matthijnssens, J. Whole genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of a zoonotic human G8P[14] rotavirus strain. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2010, 10, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degiuseppe, J.I.; Torres, C.; Mbayed, V.A.; Stupka, J.A. Phylogeography of Rotavirus G8P[8] Detected in Argentina: Evidence of Transpacific Dissemination. Viruses 2022, 14, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degiuseppe, J.I.; Stupka, J.A.; Argentinian Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Emergence of unusual rotavirus G9P[4] and G8P[8] strains during post vaccination surveillance in Argentina, 2017–2018. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021, 93, 104940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshimura, Y.; Nakagomi, T.; Nakagomi, O. The relative frequencies of G serotypes of rotaviruses recovered from hospitalized children with diarrhea: A 10-year survey (1987–1996) in Japan with a review of globally collected data. Microbiol. Immunol. 2000, 44, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentsch, J.R.; Laird, A.R.; Bielfelt, B.; Griffin, D.D.; Banyai, K.; Ramachandran, M.; Jain, V.; Cunliffe, N.A.; Nakagomi, O.; Kirkwood, C.D.; et al. Serotype diversity and reassortment between human and animal rotavirus strains: Implications for rotavirus vaccine programs. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, S146–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.; Hoshino, Y. Global distribution of rotavirus serotypes/genotypes and its implication for the development and implementation of an effective rotavirus vaccine. Rev. Med. Virol. 2005, 15, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, S.; Page, N.A.; Duncan Steele, A.; Peenze, I.; Cunliffe, N.A. Rotavirus strain types circulating in Africa: Review of studies published during 1997–2006. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, S34–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunliffe, N.A.; Ngwira, B.M.; Dove, W.; Thindwa, B.D.; Turner, A.M.; Broadhead, R.L.; Molyneux, M.E.; Hart, C.A. Epidemiology of rotavirus infection in children in Blantyre, Malawi, 1997–2007. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, S168–S174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, T.; Doan, Y.H.; Dove, W.; Ngwira, B.; Iturriza-Gómara, M.; Nakagomi, O.; Cunliffe, N.A. G8 rotaviruses with conserved genotype constellations detected in Malawi over 10 years (1997–2007) display frequent gene reassortment among strains co-circulating in humans. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 1273–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, P.; Tan, M.; Liu, Y.; Biesiada, J.; Meller, J.; Castello, A.A.; Jiang, B.; Jiang, X. Rotavirus VP8*: Phylogeny, host range, and interaction with histo-blood group antigens. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 9899–9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tan, M. Histo-blood group antigens as receptors for rotavirus, new understanding on rotavirus epidemiology and vaccine strategy. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2017, 6, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, N.; Esona, M.; Seheri, M.; Nyangao, J.; Bos, P.; Mwenda, J.; Steele, A.D.; Mphahlele, J. Characterization of genotype G8 strains from Malawi, Kenya, and South Africa. J. Med. Virol. 2010, 82, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chege, G.K.; Steele, A.D.; Hart, C.A.; Snodgrass, D.R.; Omolo, E.O.; Mwenda, J.M. Experimental infection of non-human primates with a human rotavirus isolate. Vaccine 2005, 23, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adah, M.I.; Nagashima, S.; Wakuda, M.; Taniguchi, K. Close relationship between G8-serotype bovine and human rotaviruses isolated in Nigeria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 3945–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoto, S.; Adah, M.I.; Ide, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Taniguchi, K. Whole genomic analysis of human and bovine G8P[1] rotavirus strains isolated in Nigeria provides evidence for direct bovine-to-human interspecies transmission. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 43, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Mijatovic-Rustempasic, S.; Roy, S.; Esona, M.D.; Lopez, B.; Mencos, Y.; Rey-Benito, G.; Bowen, M.D. Full genomic characterization and phylogenetic analysis of a zoonotic human G8P[14] rotavirus strain detected in a sample from Guatemala. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 33, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okitsu, S.; Hikita, T.; Thongprachum, A.; Khamrin, P.; Takanashi, S.; Hayakawa, S.; Maneekarn, N.; Ushijima, H. Detection and molecular characterization of two rare G8P[14] and G3P[3] rotavirus strains collected from children with acute gastroenteritis in Japan. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 62, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandera, E.A.; Akari, Y.; Sang, C.; Njugu, P.; Khamadi, S.A.; Musundi, S.; Mutua, M.M.; Fukuda, S.; Murata, T.; Inoue, S.; et al. Full genome characterization of a Kenyan G8P[14] rotavirus strain suggests artiodactyl-to-human zoonotic transmission. Trop. Med. Health 2025, 53, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medici, M.C.; Abelli, L.A.; Martinelli, M.; Dettori, G.; Chezzi, C. Molecular characterization of VP4, VP6 and VP7 genes of a rare G8P[14] rotavirus strain detected in an infant with gastroenteritis in Italy. Virus Res. 2008, 137, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Potgieter, C.A.; Ciarlet, M.; Parreño, V.; Martella, V.; Bányai, K.; Garaicoechea, L.; Palombo, E.A.; Novo, L.; Zeller, M.; et al. Are human P[14] rotavirus strains the result of interspecies transmissions from sheep or other ungulates that belong to the mammalian order Artiodactyla? J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2917–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, S.; Arias, C.F. Multistep entry of rotavirus into cells: A Versaillesque dance. Trends Microbiol. 2004, 12, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, R.; Fleming, F.E.; Maggioni, A.; Dang, V.T.; Holloway, G.; Coulson, B.S.; von Itzstein, M.; Haselhorst, T. Revisiting the role of histo-blood group antigens in rotavirus host-cell invasion. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Kennedy, M.A.; Wang, D.; Li, F. The role and implication of rotavirus VP8* in viral infection and vaccine development. Virology 2025, 609, 110563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, T.; Horie, Y.; Koshimura, Y.; Greenberg, H.B.; Nakagomi, O. Isolation of a human rotavirus strain with a super-short RNA pattern and a new P2 subtype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Nakagomi, T.; Nakagomi, O. Molecular identification of a novel G1 VP7 gene carried by a human rotavirus with a super-short RNA pattern. Virus Genes 2007, 35, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, L.P.; Nakagomi, T.; Nakagomi, O. A rare G1P[6] super-short human rotavirus strain carrying an H2 genotype on the genetic background of a porcine rotavirus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 21, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, S.; Hasegawa, A.; Mukoyama, A.; Inouye, S. A candidate for a new serotype of human rotavirus. J. Virol. 1985, 54, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, M.J.; Unicomb, L.E.; Bishop, R.F. Cultivation and characterization of human rotaviruses with “super short” RNA patterns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1987, 25, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, H.; László, B.; Jakab, F.; Ganesh, B.; De Grazia, S.; Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; Martella, V.; Bányai, K. Review of group A rotavirus strains reported in swine and cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 165, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyer, A.; Poljsak-Prijatelj, M.; Barlic-Maganja, D.; Jamnikar, U.; Mijovski, J.Z.; Marin, J. Molecular characterization of a new porcine rotavirus P genotype found in an asymptomatic pig in Slovenia. Virology 2007, 359, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Inaba, Y.; Shinozaki, T.; Fujii, R.; Matumoto, M. Isolation of human rotavirus in cell cultures: Brief report. Arch. Virol. 1981, 69, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoroff, T.A.; Tsunemitsu, H.; Okamoto, K.; Katsuda, K.; Kohmoto, M.; Kawashima, K.; Nakagomi, T.; Nakagomi, O. Predominance of porcine rotavirus G9 in Japanese piglets with diarrhea: Close relationship of their VP7 genes with those of recent human G9 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, L.P.; Nakagomi, T.; Otaki, H.; Agbemabiese, C.A.; Nakagomi, O.; Tsunemitsu, H. Phylogenetic inference of the porcine Rotavirus A origin of the human G1 VP7 gene. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 40, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arista, S.; Giammanco, G.M.; De Grazia, S.; Ramirez, S.; Lo Biundo, C.; Colomba, C.; Cascio, A.; Martella, V. Heterogeneity and temporal dynamics of evolution of G1 human rotaviruses in a settled population. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 10724–10733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, M.; Shimada, S.; Fujii, Y.; Moriyama, H.; Oba, M.; Katayama, Y.; Tsuchiaka, S.; Okazaki, S.; Omatsu, T.; Furuya, T.; et al. H2 genotypes of G4P[6], G5P[7], and G9[23] porcine rotaviruses show super-short RNA electropherotypes. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 176, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shizawa, S.; Fukuda, F.; Kikkawa, Y.; Oi, T.; Takemae, H.; Masuda, T.; Ishida, H.; Murakami, H.; Sakaguchi, S.; Mizutani, T.; et al. Genomic diversity of group A rotaviruses from wild boars and domestic pigs in Japan: Wide prevalence of NSP5 carrying the H2 genotype. Arch. Virol. 2024, 169, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennehy, J.J. Evolutionary ecology of virus emergence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1389, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoa-Tran, T.N.; Nakagomi, T.; Vu, H.M.; Kataoka, C.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Dao, A.T.H.; Nguyen, A.T.; Takemura, T.; Hasebe, F.; Dang, A.D.; et al. Whole genome characterization of feline-like G3P[8] reassortant rotavirus A strains bearing the DS-1-like backbone genes detected in Vietnam, 2016. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 73, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa-Tran, T.N.; Nakagomi, T.; Vu, H.M.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Takemura, T.; Hasebe, F.; Dao, A.T.H.; Anh, P.H.Q.; Nguyen, A.T.; Dang, A.D.; et al. Detection of three independently-generated DS-1-like G9P[8] reassortant rotavirus A strains during the G9P[8] dominance in Vietnam, 2016-2018. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 80, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.M. The Rotavirus Interferon Antagonist NSP1: Many Targets, Many Questions. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5212–5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bwogi, J.; Karamagi, C.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Tushabe, P.; Kiguli, S.; Namuwulya, P.; Malamba, S.S.; Jere, K.C.; Desselberger, U.; Iturriza-Gomara, M. Co-Surveillance of Rotaviruses in Humans and Domestic Animals in Central Uganda Reveals Circulation of Wide Genotype Diversity in the Animals. Viruses 2023, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.V.T.; Anh, P.H.; Cuong, N.V.; Munnink, B.B.O.; van der Hoek, L.; My, P.T.; Tri, T.N.; Bryant, J.E.; Baker, S.; Thwaites, G.; et al. Unbiased whole-genome deep sequencing of human and porcine stool samples reveals circulation of multiple groups of rotaviruses and a putative zoonotic infection. Virus Evol. 2016, 2, vew027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, D.E.; Parashar, U.D.; Jiang, B. Strain diversity plays no major role in the varying efficacy of rotavirus vaccines: An overview. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 28, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbemabiese, C.A.; Nakagomi, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Armah, G.; Nakagomi, O. Evolution of a G6P[6] rotavirus strain isolated from a child with acute gastroenteritis in Ghana, 2012. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 2219–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.F.; Purcell, D.F.J.; Howden, B.P.; Duchene, S. Evolutionary rate of SARS-CoV-2 increases during zoonotic infection of farmed mink. Virus Evol. 2023, 9, vead002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruuska, T.; Vesikari, T. Rotavirus disease in Finnish children: Use of numerical scores for clinical severity of diarrhoeal episodes. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1990, 22, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagomi, T.; Nguyen, M.Q.; Gauchan, P.; Agbemabiese, C.A.; Kaneko, M.; Do, L.P.; Vu, T.D.; Nakagomi, O. Evolution of DS-1-like G1P[8] double-gene reassortant rotavirus A strains causing gastroenteritis in children in Vietnam in 2012/2013. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.M.; Nelson, M.I.; Turner, P.E.; Patton, J.T. Reassortment in segmented RNA viruses: Mechanisms and outcomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, Y.; Kobayashi, T. Rotavirus reverse genetics systems: Development and application. Virus Res. 2021, 295, 198296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoto, S.; Fukuda, S.; Murata, T.; Taniguchi, K. Human Rotavirus Reverse Genetics Systems to Study Viral Replication and Pathogenesis. Viruses 2021, 13, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakagomi, T.; Nakagomi, O. Interspecies Transmission of Animal Rotaviruses to Humans: Reassortment-Driven Adaptation. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121230

Nakagomi T, Nakagomi O. Interspecies Transmission of Animal Rotaviruses to Humans: Reassortment-Driven Adaptation. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121230

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakagomi, Toyoko, and Osamu Nakagomi. 2025. "Interspecies Transmission of Animal Rotaviruses to Humans: Reassortment-Driven Adaptation" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121230

APA StyleNakagomi, T., & Nakagomi, O. (2025). Interspecies Transmission of Animal Rotaviruses to Humans: Reassortment-Driven Adaptation. Pathogens, 14(12), 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121230