Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Clones Are Widely Distributed in the Hospital and Community

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

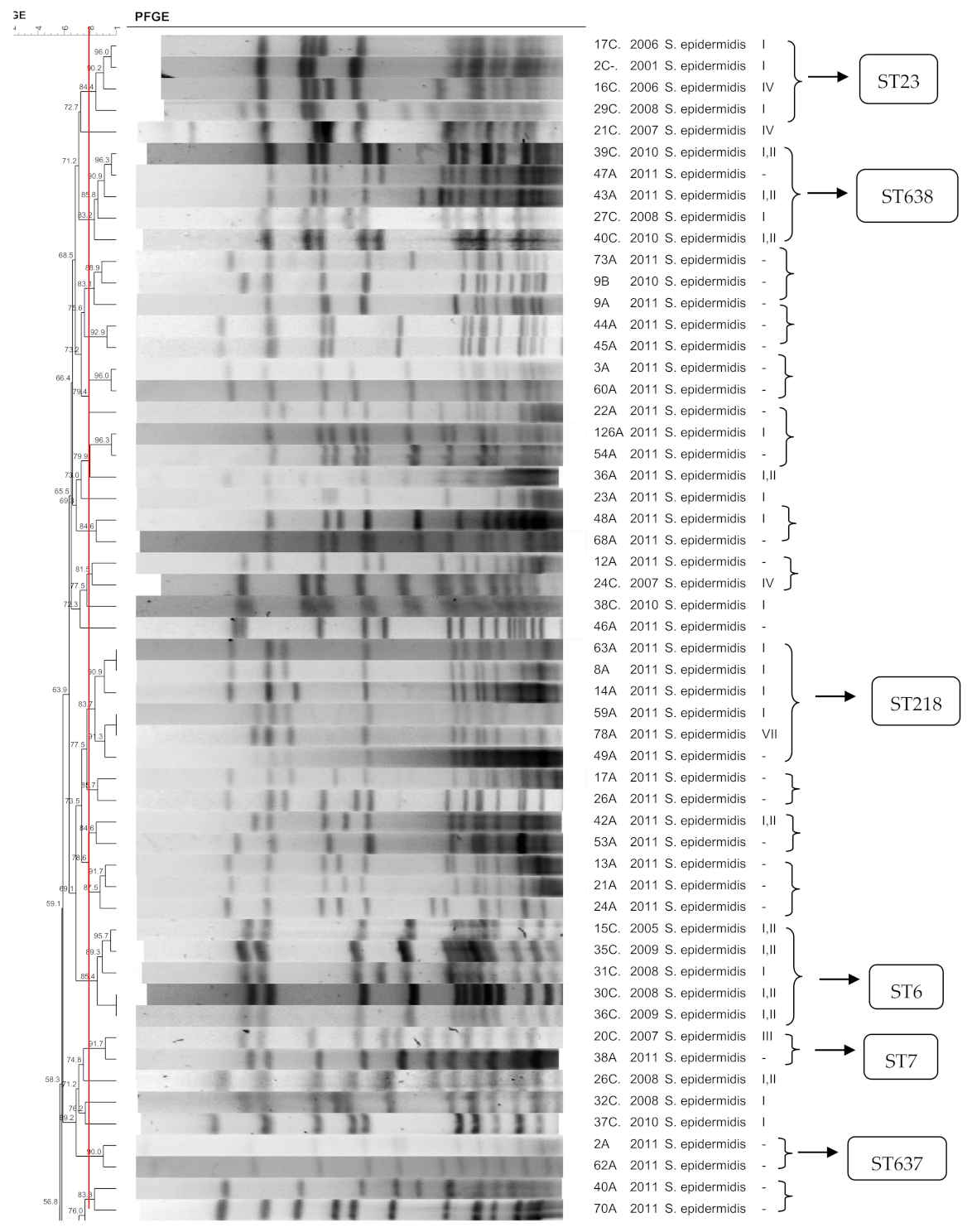

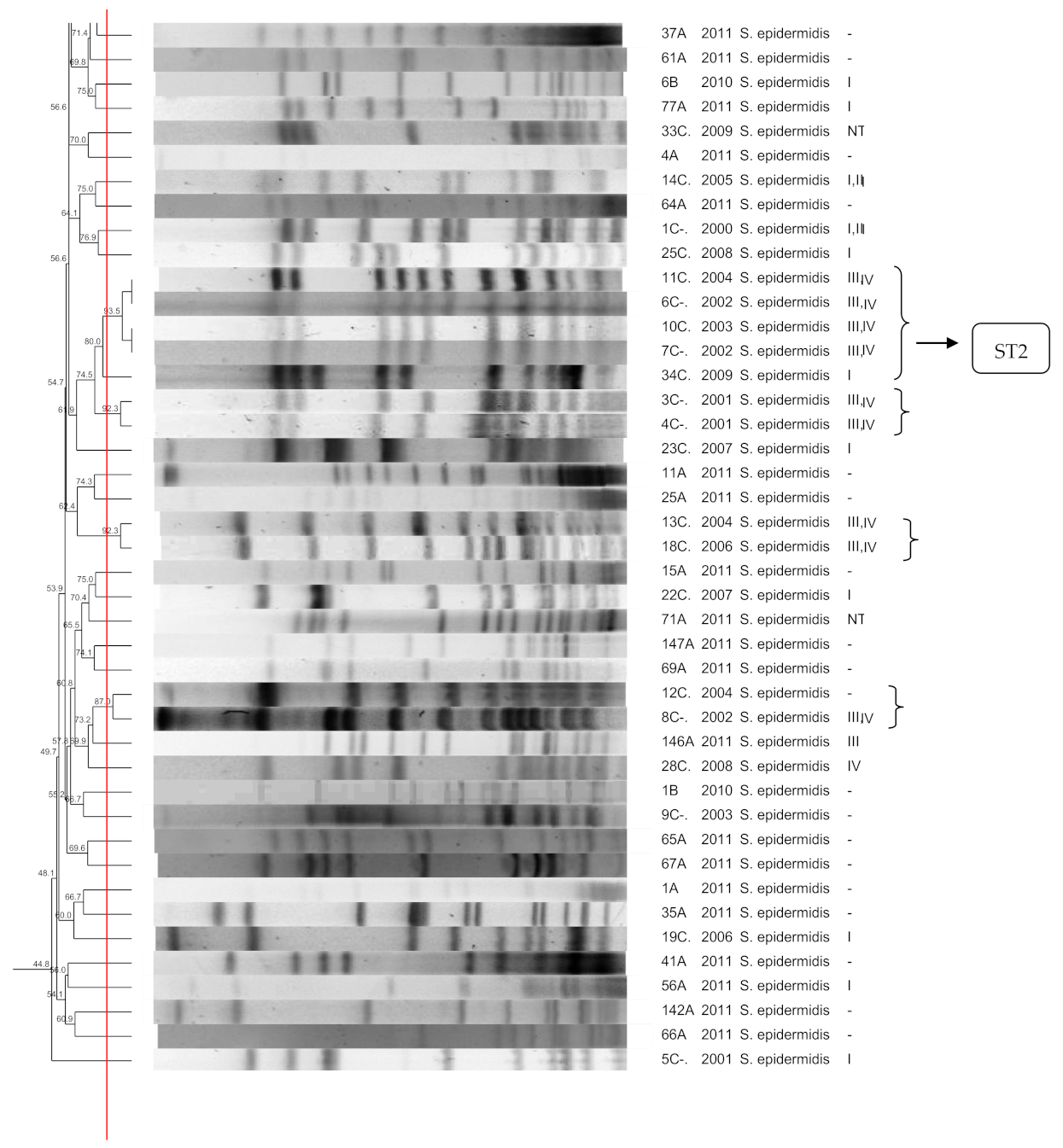

3.1. S. epidermidis

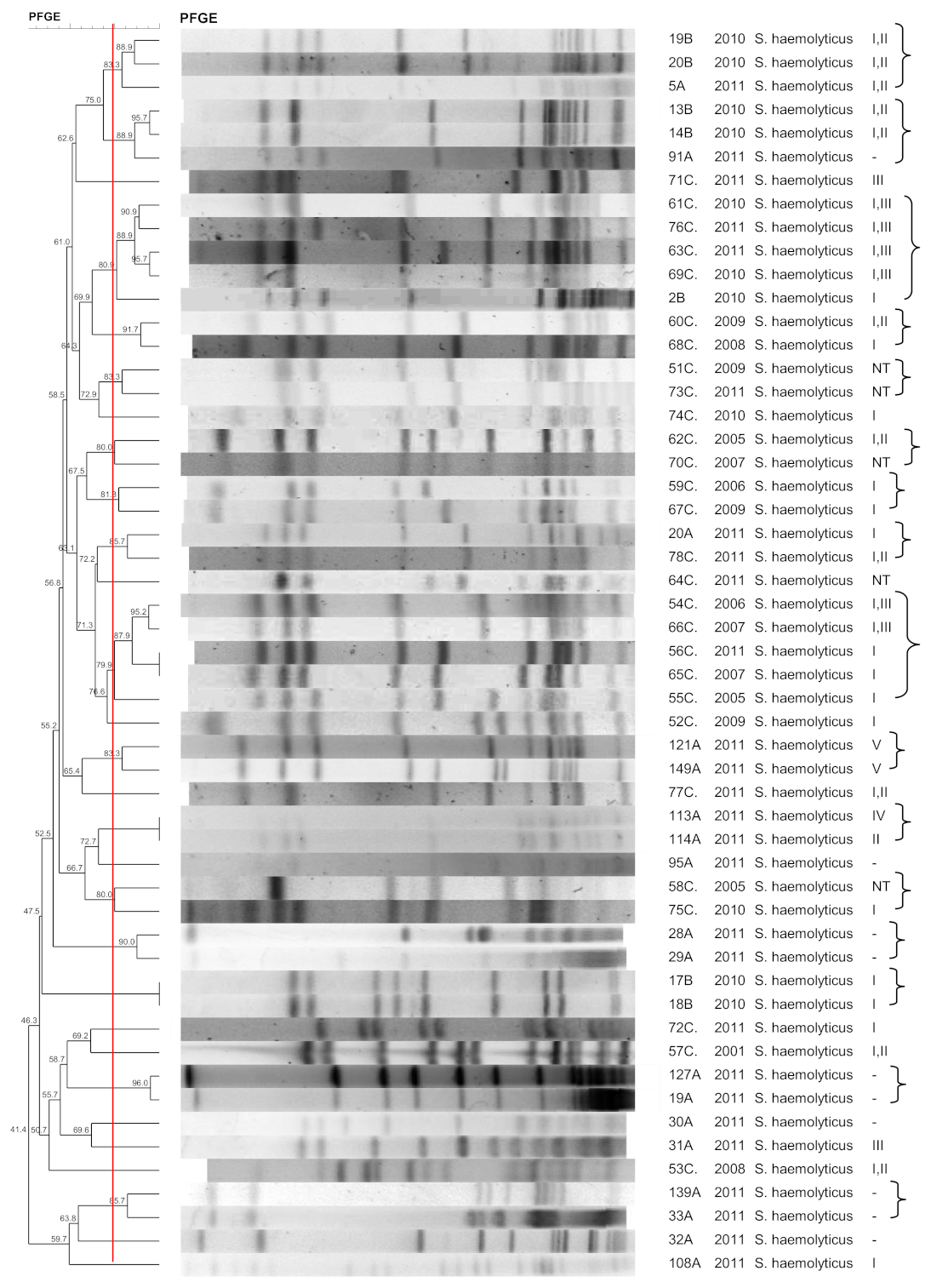

3.2. S. haemolyticus

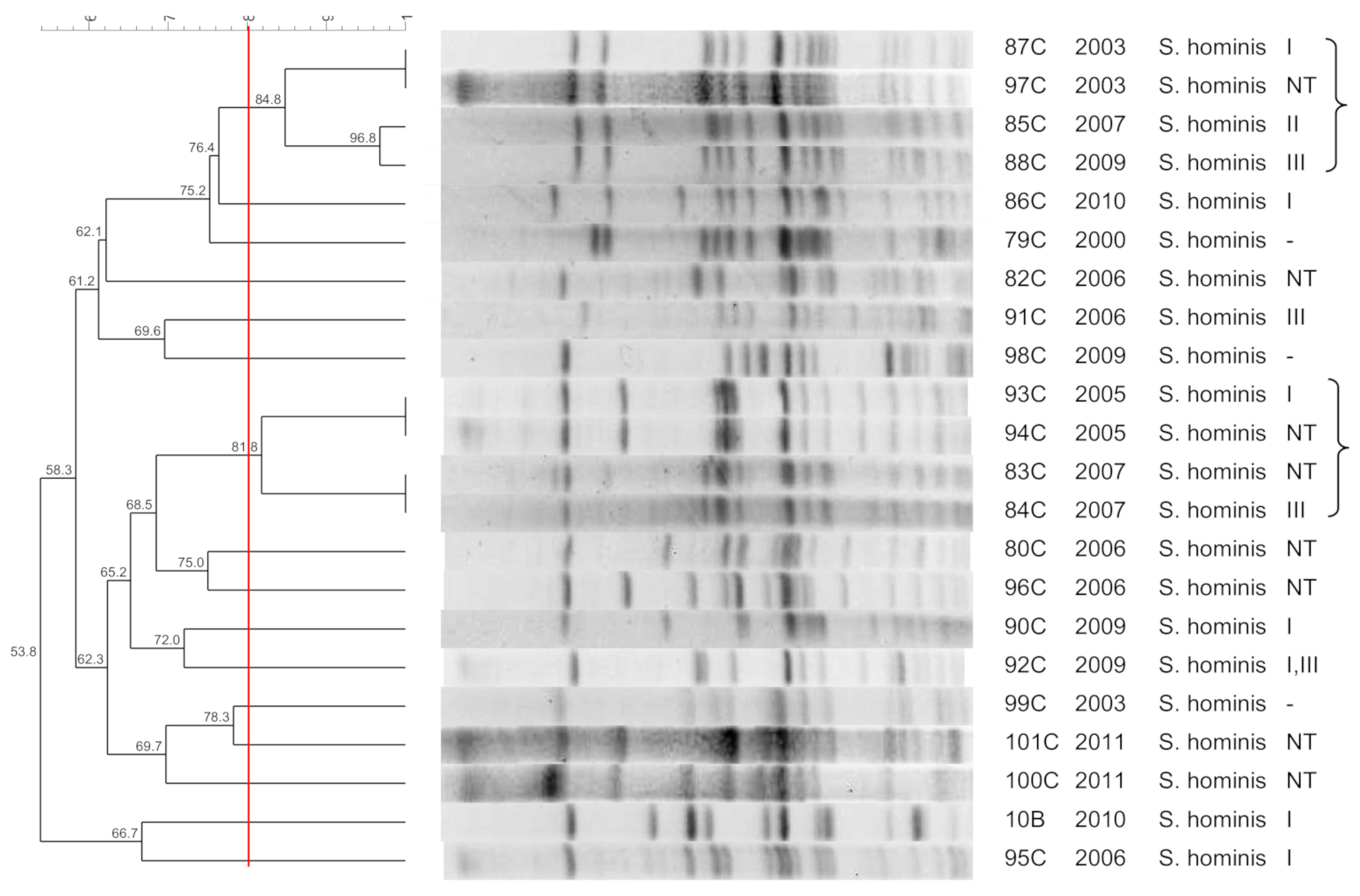

3.3. S. hominis

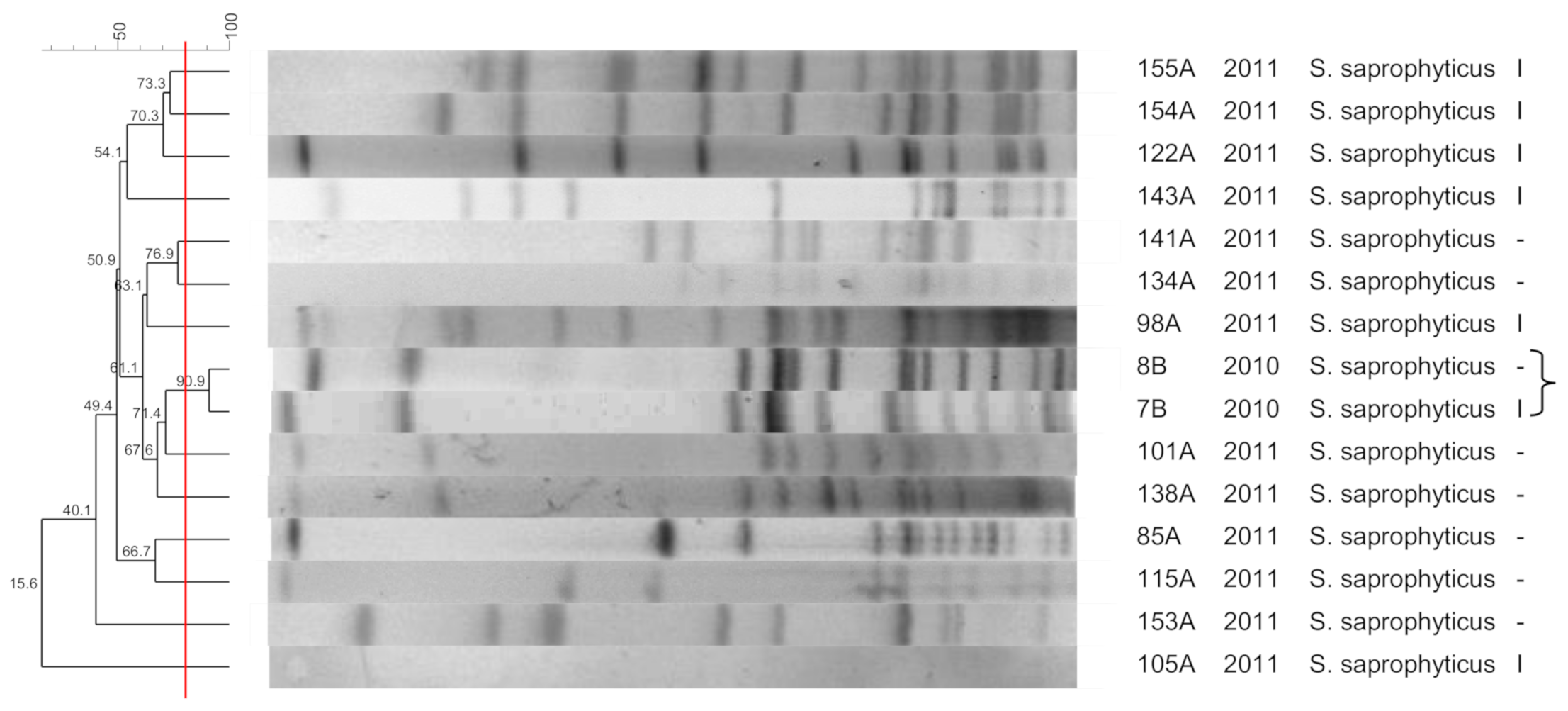

3.4. S. saprophyticus

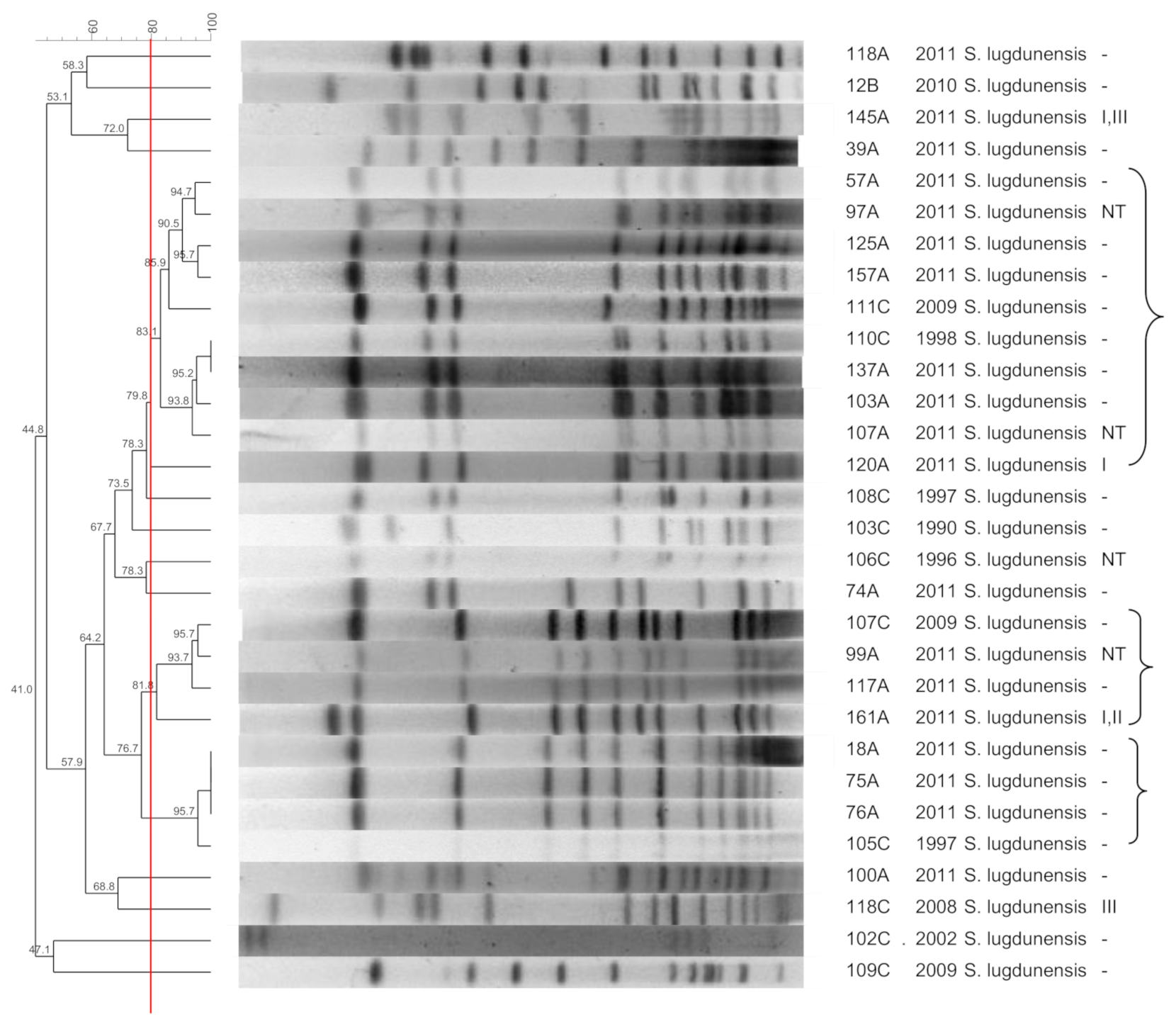

3.5. S. lugdunensis

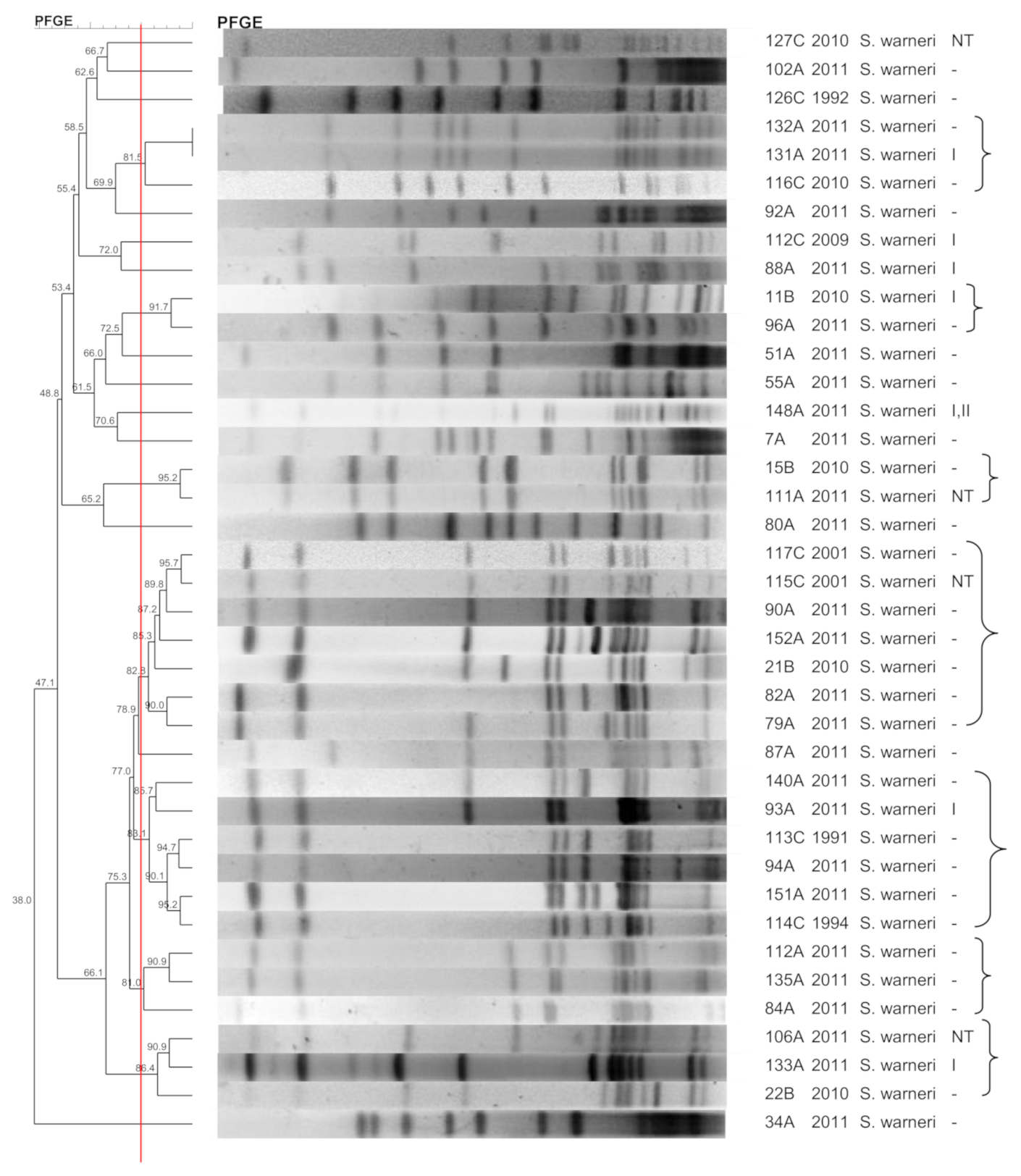

3.6. S. warneri

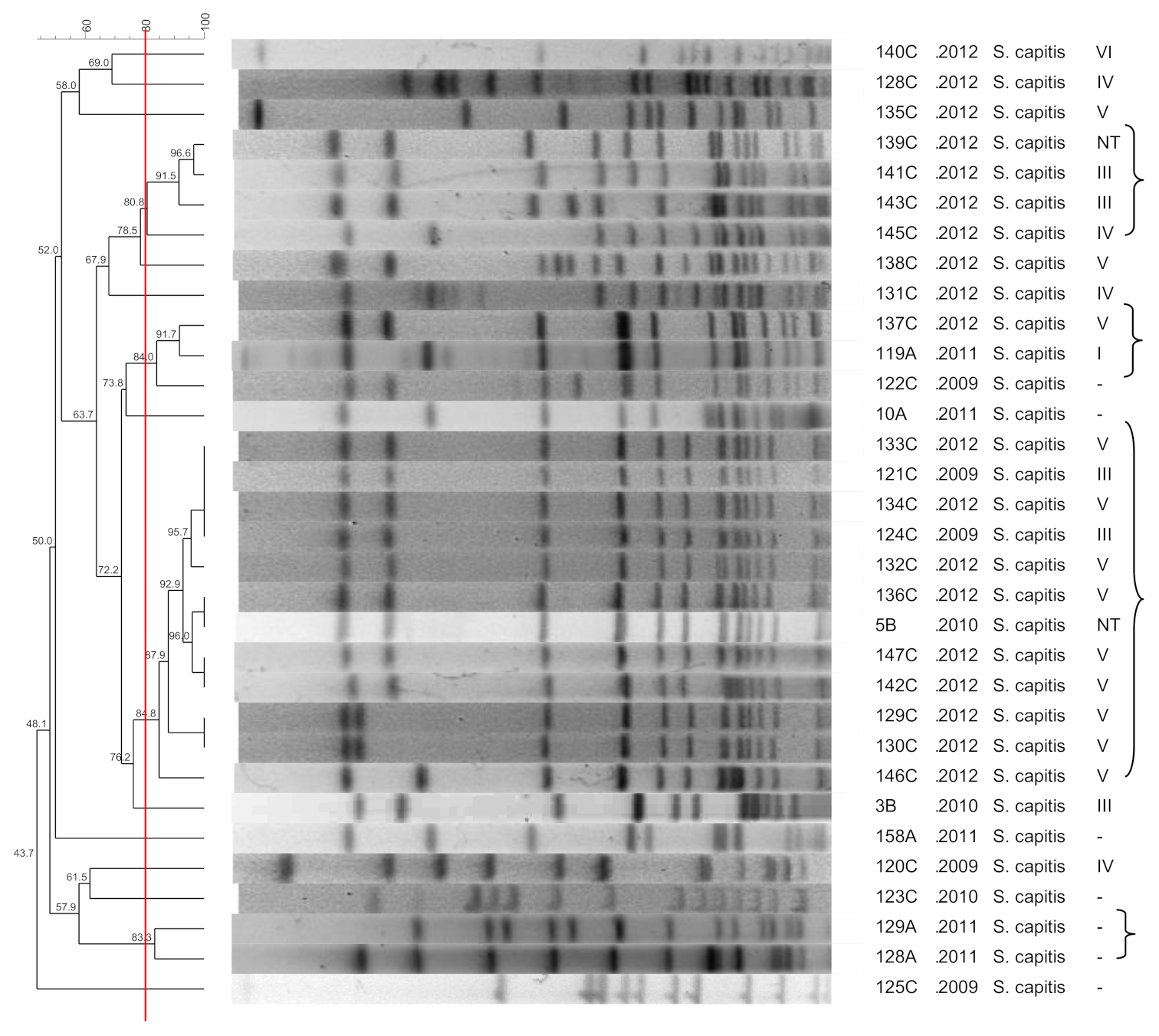

3.7. S. capitis

3.8. S. pasteuri

3.9. S. simulans

3.10. SCCmec

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolates

4.2. Identification of CoNS

4.3. PFGE Typing

4.4. SCCmec Typing

4.5. MLST

4.6. Diversity Index

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kloos, W.; Schleifer, K.H. Genus IV. Staphylococcus. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology; Sneath, P.H.A., Mair, N., Sharpe, M.E., Holt, J.G., Eds.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1986; pp. 1013–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, M. Staphylococcus epidermidis—The ‘accidental’ pathogen. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, P.; Garrity, G.; Jones, D.; Krieg, N.R.; Ludwig, W.; Rainey, F.A.; Schleifer, K.-H.; Whitman, W. The Firmicutes. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloos, W.E.; Bannerman, T.L. “Staphylococcus and Micrococcus”. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 6th ed.; Murray, P.R., Baron, E.J., Pfaller, M.A., Tenover, F.C., Yolken, R.H., Eds.; American Society Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 264–282. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, K.C.; Pfaller, M.A.; Landry, M.L.; McAdam, A.J.; Patel, R.; Richter, S.S.; Warnock, D.W. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 12th ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. 2832. [Google Scholar]

- Michels, R.; Last, K.; Becker, S.L.; Papan, C. Update on Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci—What the Clinician Should Know. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikens, E.; Fleer, A.; Paauw, A.; Florijn, A.; Fluit, A.C. Comparison of genotypic and phenotypic methods for species-level identification of clinical isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 2286–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbier, F.; Ruppé, E.; Hernandez, D.; Lebeaux, D.; Francois, P.; Felix, B.; Ruimy, R. Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci in the community: High homology of SCCmecIVa between Staphylococcus epidermidis and major clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekema, D.J.; Pfaller, M.A.; Schmitz, F.J.; Smayevsky, J.; Bell, J.; Jones, R.N.; Beach, M.; SENTRY Participants Group. Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: Frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, S114. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T.; Ma, X.X.; Takeuchi, F.; Okuma, K.; Yuzawa, H.; Hiramatsu, K. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 2637–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhu, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, T.; Luo, T.; Sun, G.; Yang, C.; Cao, C.; Lu, Y.; Li, M. Molecular analysis of Staphylococcus epidermidis strains isolated from community and hospital environments in China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miragaia, M.; Thomas, J.C.; Couto, I.; Enright, M.C.; de Lencastre, H. Inferring a population structure for Staphylococcus epidermidis from Multilocus Sequence Typing Data. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 2540–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, X.; Gao, Q.; Lu, Y. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus epidermidis strains isolated from a teaching hospital in Shanghai, China. J. Med. Microbiol. 2009, 58, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miragaia, M.; Carriço, J.A.; Thomas, J.C.; Couto, I.; Enright, M.C.; de Lencastre, H. Comparison of molecular typing methods for characterization of Staphylococcus epidermidis: Proposal for clone definition. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Mee-Marquet, N.; Achard, A.; Mereghetti, L.; Danton, A.; Minier, M.; Quentin, R. Staphylococcus lugdunensis Infections: High frequency of inguinal area carriage. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolosi, D.; Cinà, D.; Di Naso, C.; D’Angeli, F.; Salmeri, M.; Genovese, C. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiling of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci in a Referral Center in South Italy: A Surveillance Study. Open Microbiol. 2020, 14, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherifi, S.; Byl, B.; Deplano, A.; Nonhoff, C.; Denis, O.; Hallin, M. Comparative epidemiology of Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from patients with catheter-related bacteremia and from healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogado, J.; Limansky, A.; Sutich, E.; Marchiaro, P.; Marzi, M.; Putero, J.; Viale, A. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci from a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2002, 23, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolo, J.; de Lencastre, H.; Miragaia, M. Strategies of adaptation of Staphylococcus epidermidis to hospital and community: Amplification and diversification of SCCmec. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.P.; Teixeira, L.M.; Bastos, C.C.; Silva, M.G.; Ferreira, R.B.; Fonseca, L.S.; Santos, K.R. Genomic characterization of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus haemolyticus isolated from Brazilian medical centres. J. Hosp. Infect. 2005, 59, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Meléndez, A.; Morfín-Otero, R.; Villarreal-Treviño, L.; Camacho-Ortíz, A.; González-González, G.; Llaca-Díaz, J.; Rodriguez-Noriega, E.; Garza-González, E. Molecular epidemiology of coagulase-negative bloodstream isolates: Detection of Staphylococcus epidermidis ST2, ST7 and linezolid-resistant ST23. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, G.; Bhandari, V.; Gaind, R.; Rani, V.; Chopra, S.; Dawar, R.; Sardana, R.; Verma, P.K. Linezolid resistant coagulase negative staphylococci (LRCoNS) with novel mutations causing blood stream infections (BSI) in India. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosecka-Strojek, M.; Sadowy, E.; Gawryszewska, I.; Klepacka, J.; Tomasik, T.; Michalik, M.; Hryniewicz, W.; Miedzobrodzki, J. Emergence of linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis in the tertiary children’s hospital in Cracow, Poland. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, C.; Ruiz-García, M.; Gómez-Sanz, E.; López-García, P.; Royo-García, G.; Zarazaga, M.; Torres, C. Characterization of a cfr-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain of the lineage ST22 implicated in a life-threatening human infection. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 73, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.E.; Deshpande, L.M.; Farrell, D.J.; Spanu, T.; Fadda, G.; Jones, R.N. Assessment of linezolid resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus epidermidis causing bacteraemia in Rome, Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgueiro, V.C.; Iorio, N.L.P.; Ferreira, M.C.; Chamon, R.C.; Santos, K.R.N. Methicillin resistance and virulence genes in invasive and nasal Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from neonates. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, L.M.; Lincopan, N.; Araújo, M.R.E.; Mamizuka, E.M. Dissemination of the linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis clone ST2 exhibiting the G2576T mutation in the 23S rRNA gene in a tertiary-care hospital, Brazil. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 768–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Satorius, A.E.; Raff, M.R.; Rivera, A.; Newton, D.W.; Younger, J.G. Multilocus Sequence Typing for interpreting blood isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2014, 787458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, F.; Watanabe, S.; Baba, T.; Yuzawa, H.; Ito, T.; Morimoto, Y.; Kuroda, M.; Cui, L.; Takahashi, M.; Ankai, A.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing of Staphylococcus haemolyticus uncovers the extreme plasticity of its genome and the evolution of human-colonizing Staphylococcal species. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 7292–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, E.M.; Ceotto, H.; Bastos, M.C.F.; dos Santos, K.R.N.; Giambiagi-deMarval, M. Staphylococcus haemolyticus as an Important Hospital Pathogen and Carrier of Methicillin Resistance Genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Chen, Y.G.; Yu, Y.S.; Chen, C.L.; Li, L.J. Antimicrobial resistance and molecular characterization of Staphylococcus haemolyticus in a Chinese hospital. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 29, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchami, O.; Hassen, A.B.; de Lencastre, H.; Miragaia, M. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus hominis (MRSHo): Low clonality and reservoirs of SCCmec structural elements. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.B.M.P.; Reiter, K.C.; Paiva, R.M.; Barth, A.L. Distribution of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types I, II, III, and IV in coagulase-negative staphylococci from patients attending a tertiary hospital in southern Brazil. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Olazarán, S.; Morfin-Otero, R.; Rodríguez-Noriega, E.; Llaca-Díaz, J.; Flores-Treviño, S.; González-González, G.M.; Villarreal-Treviño, L.; Garza-González, E. Microbiological and molecular characterization of Staphylococcus hominis isolates from blood. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.S.; Rabello, R.F.; Dias, R.C.S.; Martins, I.S.; Santos, L.B.G.S.; Alves, E.M.; Riley, L.W.; Moreira, B.M. Time-based distribution of Staphylococcus saprophyticus pulsed field gel-electrophoresis clusters in community-acquired urinary tract infections. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2013, 108, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widerström, M.; Wiström, J.; Ferry, S.; Karlsson, C.; Monsen, T. Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus saprophyticus isolated from women with uncomplicated community-acquired urinary tract infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poutanen, S.M. Staphylococcus lugdunensis: A notably distinct coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. Clin. Microbiol. News. Lett. 2001, 23, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourtet-Hascoët, J.; Bicart-See, A.; Félicé, M.P.; Giordano, G.; Bonnet, E. Staphylococcus lugdunensis, a serious pathogen in periprosthetic joint infections: Comparison to Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 51, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, J.; Poitevin-Later, F.; Renaud, F.; Fleurette, J. Plasmid profiles and genomic DNA restriction endonuclease patterns of 30 independent Staphylococcus lugdunensis strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990, 55, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttery, J.P.; Easton, M.; Pearson, S.R.; Hogg, G.G. Pediatric bacteremia due to Staphylococcus warneri: Microbiological, epidemiological, and clinical features. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 2174–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamoto, I.; Ishihara, Y.; Sato, A.; Usami, H.; Matsuda, N.; Ohta, M. Dissemination of Staphylococcus warneri in the Hair of ICU Doctors. Adv. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Silva, G.D.I.; Justice, A.; Wilkinson, A.R.; Buttery, J.; Herbert, M.; Day, N.P.J.; Peacock, S.J. Genetic population structure of coagulase-negative staphylococci associated with carriage and disease in preterm infants. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haqan, A.; Boswihi, S.S.; Pathan, S.; Udo, E.E. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence determinants in coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated mainly from preterm neonates. PLoS ONE 2020, 4, e0236713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Smooker, P.M.; Rouch, D.A.; Daley, A.J.; Deighton, M.A. Differences between two clinical Staphylococcus capitis subspecies as revealed by biofilm, antibiotic resistance, and Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis profiling. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, S.; Arroyo, R.; Jiménez, E.; Marín, M.; del Campo, R.; Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, J.M. Staphylococcus epidermidis strains isolated from breast milk of women suffering infectious mastitis: Potential virulence traits and resistance to antibiotics. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorland, J.; Steinum, T.; Kvitle, B.; Waage, S.; Sunde, M.; Heir, E. Widespread distribution of disinfectant resistance genes among Staphylococci of bovine and caprine origin in Norway. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 4363–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiz, L.M.P.; Chuat, V.; Madec, M.N.; Araújo, E.A.; Carvalho, A.F.; Valence, F. Mesophilic lactic acid bacteria diversity encountered in Brazilian farms producing milk with particular interest in Lactococcus lactis strains. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 73, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-González, E.; López, D.; Pezina, C.; Muruet, W.; Bocanegra-García, V.; Muñoz, I.; Ramírez, C.; LLaca-Díaz, J.M. Diversity of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec structures in coagulase-negative staphylococci and relationship to drug resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mørk, T.; Jørgensen, H.J.; Sunde, M.; Kvitle, B.; Sviland, S.; Waage, S.; Tollersrud, T. Persistence of staphylococcal species and genotypes in the bovine udder. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.L.; Wei, H.K.; Wang, J.; Lin, D.C.; Liu, X.Q.; Liu, J.H. High prevalence of cfr-producing Staphylococcus species in retail meat in Guangzhou, China. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, M.A.; Pletch, C.; Hussain, Z. In vitro activity of quinupristin/ dalfopristin, linezolid, telithromycin and comparator antimicrobial agents against 13 species of coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 50, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.F.; Cavanagh, J.P.; Fredheim, E.G.; Reiter, K.C.; Rieger, A.; Klingenberg, C.; d'Azevedo, P.A.; Sollid, J.E. Coagulase-negative staphylococci in Southern Brazil: Looking toward its high diversity. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2016, 49, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mašlaňová, I.; Doškař, J.; Varga, M.; Kuntová, L.; Mužík, J.; Malúšková, D.; Růžičková, V.; Pantůček, R. Bacteriophages of Staphylococcus aureus efficiently package various bacterial genes and mobile genetic elements including SCCmec with different frequencies. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013, 5, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J.P.; Kwong, S.M.; Murphy, R.J.; Yui Eto, K.; Price, K.J.; Nguyen, Q.T.; O'Brien, F.G.; Grubb, W.B.; Coombs, G.W.; Firth, N. An updated view of plasmid conjugation and mobilization in Staphylococcus. Mob. Genet. Elem. 2016, 6, e1208317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.A.; Thomas, J.; Grossman, A.D. The Bacillus subtilis conjugative transposon ICEBs1 mobilizes plasmids lacking dedicated mobilization functions. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 3165–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, F.G.; Yui Eto, K.; Murphy, R.J.; Fairhurst, H.M.; Coombs, G.W.; Grubb, W.B.; Ramsay, J.P. Origin-of-transfer sequences facilitate mobilisation of non-conjugative antimicrobial-resistance plasmids in Staphylococcus aureus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 7971–7983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L. Characterization of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Regarding Clonal Diversity and Determinants of Antimicrobial Resistance. Ph.D. Thesis, São Paulo State University, Botucatu, SP, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.S. Comparison of various methods for differentiation of staphylococci and micrococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1984, 9, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koneman, E.W.; Allen, S.D.; Janda, W.M.; Schreckenberger, P.C.; Winn, W.C., Jr. Koneman's Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology (Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology), 5th ed.; Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, M.L.R.S.; Sinzato, Y.K.; Silveira, L.V.A. Comparison of methods for identification of Coagulase-negative Staphylococci. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2004, 99, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, I.; Pereira, S.; Miragaia, M.; Sanches, I.S.; Lencastre, H. Identification of clinical staphylococcal isolates from humans by Internal Transcribed Spacer PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 3099–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellmann, A.; Becker, K.; Eiff, C.; Keckevoet, U.; Schumann, P.; Harmsen, D. Sequencing and staphylococci identification. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougal, L.K.; Steward, C.D.; Killgore, G.E.; Chaitram, J.M.; McAllister, S.K.; Tenover, F.C. Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: Establishing a National Database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 5113–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Ito, T.; Ma, X.X.; Watanabe, S.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Etienne, J.; Hiramatsu, K. Combination of multiplex PCRs for staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type assignment: Rapid identification system for mec, ccr, and major differences in junkyard regions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.C.; Vargas, M.R.; Miragaia, M.; Peacock, S.J.; Archer, G.L.; Enright, M.C. Improved Multilocus Sequence Typing scheme for Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, P.R.; Gaston, M.A. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: An application of Simpson’s index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1988, 26, 2465–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SCCmec | Nasal Colonization | Wounds | Blood Cultures |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 25 (52) | 9 (42.8) | 32 (27.6) |

| II | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| III | 3 (6.25) | 0 | 9 (7.8) |

| IV | 1 (2) | 0 | 9 (7.8) |

| V | 3 (6.25) | 0 | 12 (10.3) |

| I, III | 4 (8.3) | 0 | 16 (13.8) |

| I, II | 3 (6.25) | 4 (19) | 6 (5.2) |

| III, IV | 0 | 0 | 9 (7.8) |

| VIII | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| NT | 7 (14.6) | 8 (38) | 21 (18.1) |

| mecA negative | 97 (67) | 1 (4.5) | 16 (12.1) |

| Total | 145 (100) | 22 (100) | 132 (100) |

| Isolate | Species | Protocol 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC | ccr | mec | ||

| 78A | S. epidermidis | + | 1 + 4 | A |

| 83C | S. hominis | + | 1 | A |

| 93C | S. hominis | + | 1 | A |

| 116C | S. warneri | + | 1 + 4 + 5 | − |

| 139C | S. capitis | + | − | A + B |

| Species | Diversity Index |

|---|---|

| S. epidermidis | 0.971026 |

| S. haemolyticus | 0.984708 |

| S. warneri | 0.981087 |

| S. hominis | 0.995717 |

| S. capitis | 0.969416 |

| S. lugdunensis | 0.977062 |

| S. saprophyticus | 0.999598 |

| S. pasteuri | 0.999598 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinheiro-Hubinger, L.; Moraes Riboli, D.F.; Abraão, L.M.; Pereira Franchi, E.P.L.; Ribeiro de Souza da Cunha, M.d.L. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Clones Are Widely Distributed in the Hospital and Community. Pathogens 2021, 10, 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10070792

Pinheiro-Hubinger L, Moraes Riboli DF, Abraão LM, Pereira Franchi EPL, Ribeiro de Souza da Cunha MdL. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Clones Are Widely Distributed in the Hospital and Community. Pathogens. 2021; 10(7):792. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10070792

Chicago/Turabian StylePinheiro-Hubinger, Luiza, Danilo Flávio Moraes Riboli, Lígia Maria Abraão, Eliane Patricia Lino Pereira Franchi, and Maria de Lourdes Ribeiro de Souza da Cunha. 2021. "Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Clones Are Widely Distributed in the Hospital and Community" Pathogens 10, no. 7: 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10070792

APA StylePinheiro-Hubinger, L., Moraes Riboli, D. F., Abraão, L. M., Pereira Franchi, E. P. L., & Ribeiro de Souza da Cunha, M. d. L. (2021). Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Clones Are Widely Distributed in the Hospital and Community. Pathogens, 10(7), 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10070792