Hedgehogs and Squirrels as Hosts of Zoonotic Bartonella Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

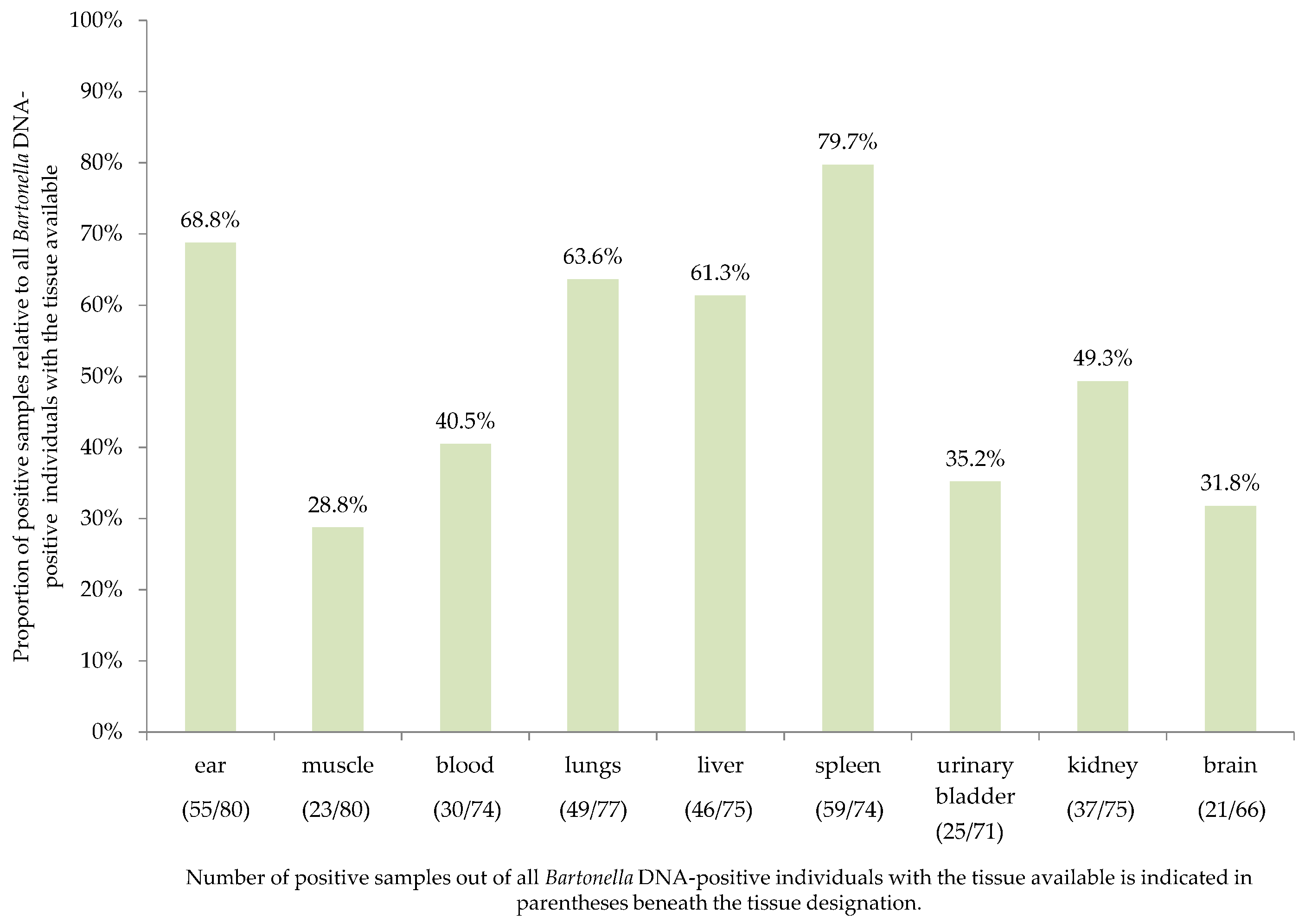

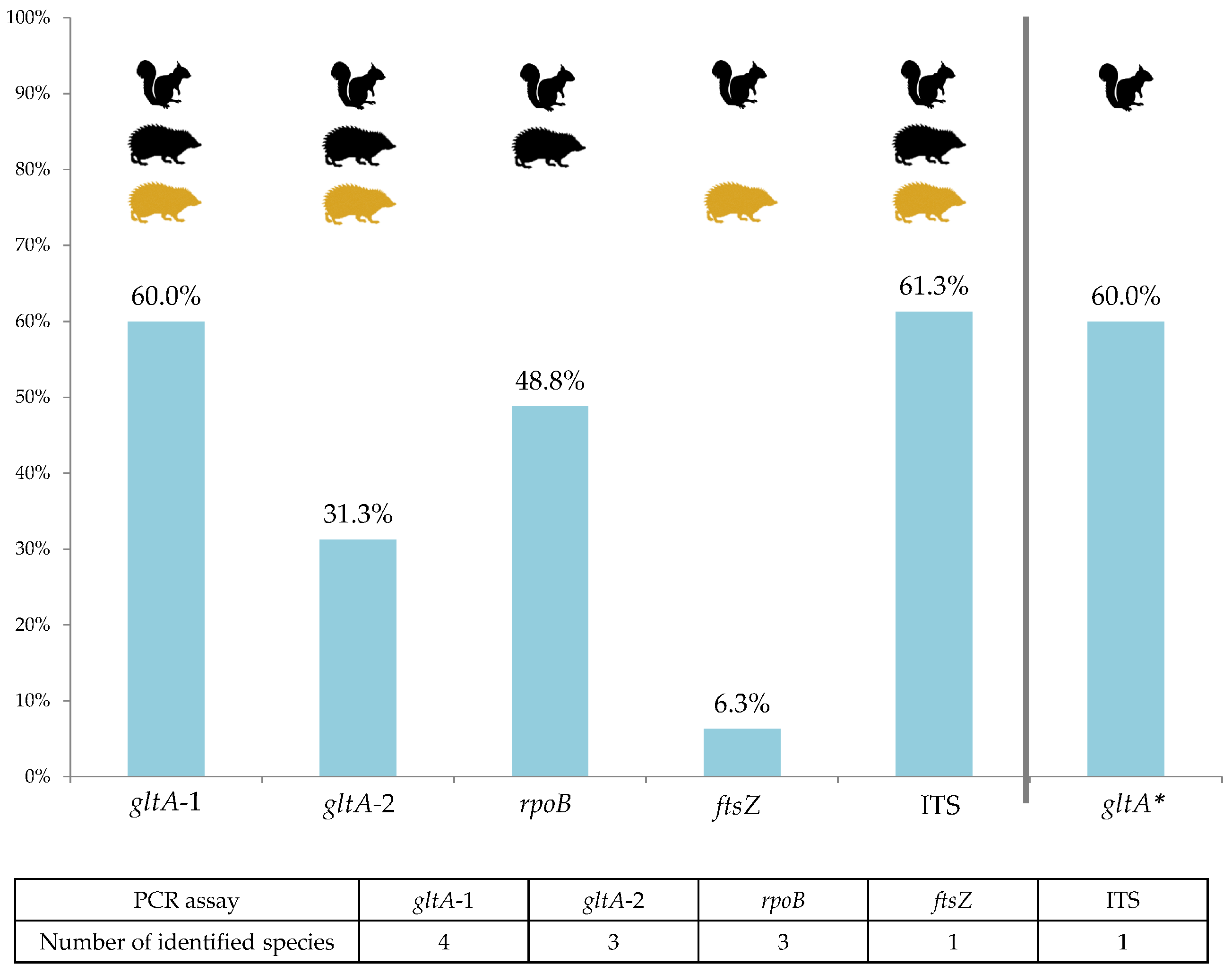

2.1. Tissue Detection Efficiency

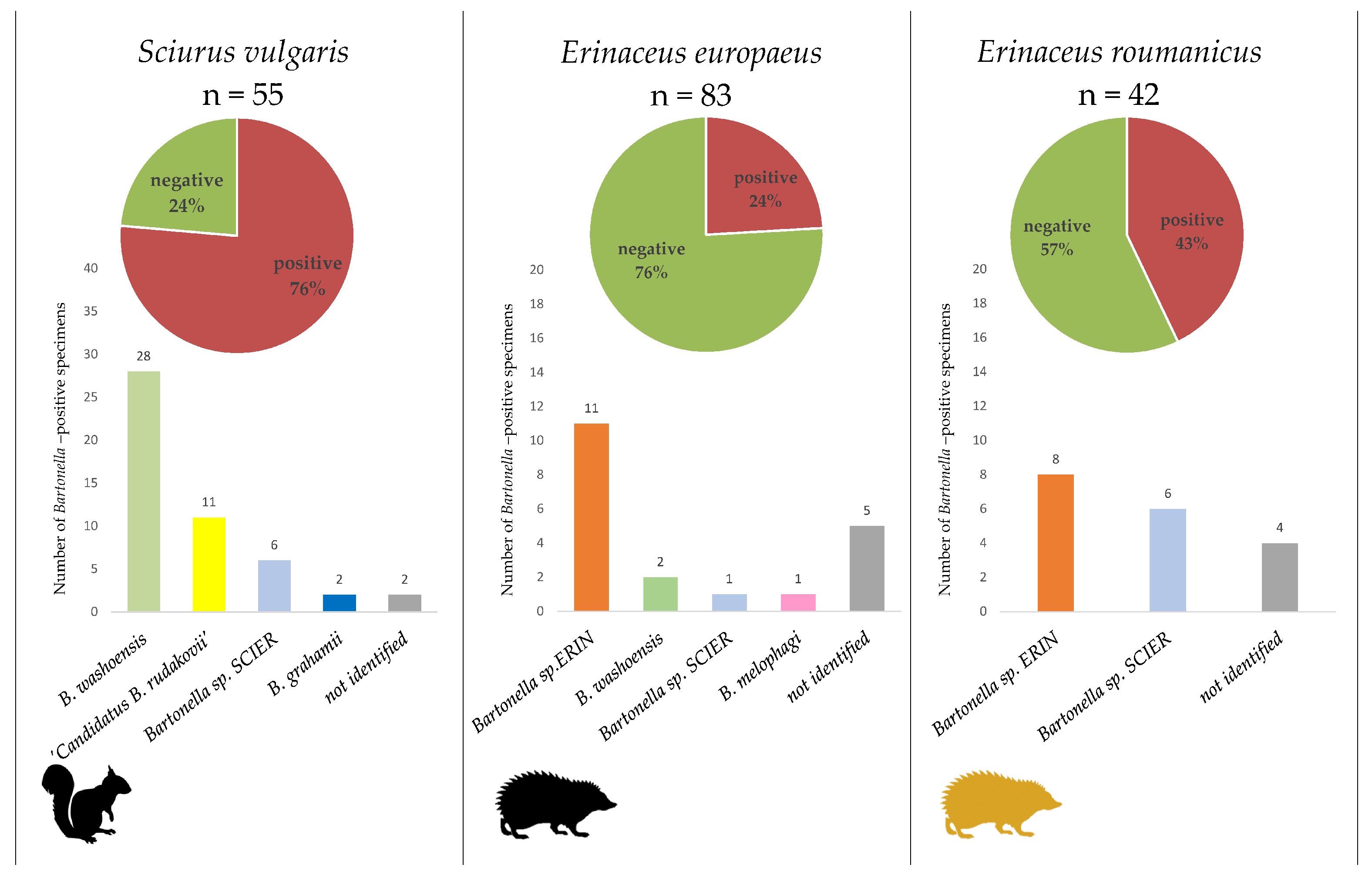

2.2. Bartonella Infection Rates and Species Identification

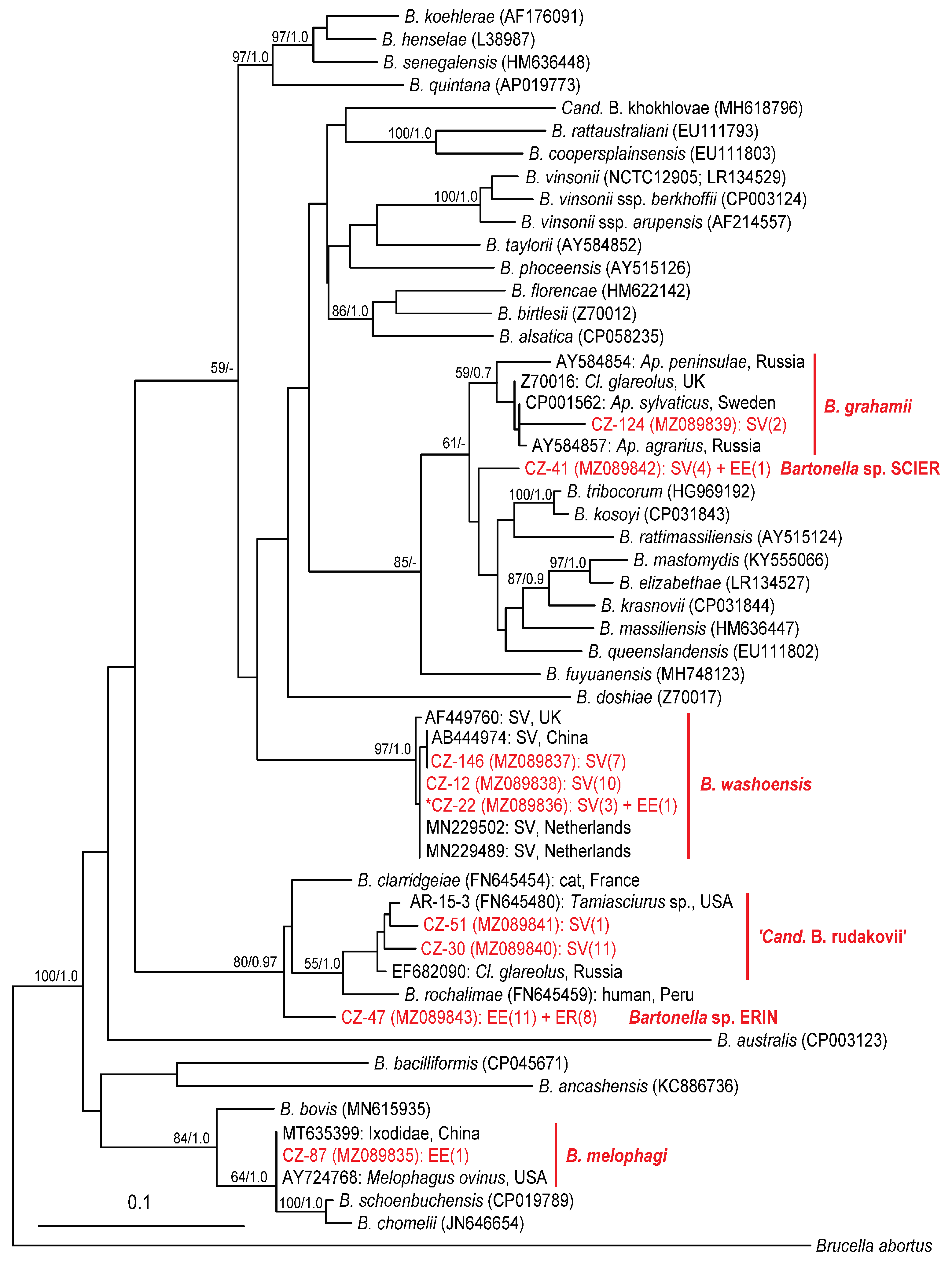

2.3. Identified Bartonella Species

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birtles, R. Bartonellae as Elegant Hemotropic Parasites. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1063, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, R.; Krasnov, B.R.; Morick, D.; Gottlieb, Y.; Khokhlova, I.S.; Harrus, S. Bartonella Infection in Rodents and Their Flea Ectoparasites: An Overview. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015, 15, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheslock, M.A.; Embers, M.E. Human Bartonellosis: An Underappreciated Public Health Problem? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taxonomy Browser of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?id=773 (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature. Available online: https://lpsn.dsmz.de/genus/bartonella (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Okaro, U.; Addisu, A.; Casanas, B.; Anderson, B. Bartonella Species, an Emerging Cause of Blood-Culture-Negative Endocarditis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 709–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, A.; Dehio, C. Intruders below the Radar: Molecular Pathogenesis of Bartonella spp. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 42–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Pang, Q.; Zhao, B.; Vayssier-Taussat, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Bartonella and Mammalian Erythrocyte Interactions: A Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, M.; Hayman, D.T.; Chan, K.-S. Bartonella bacteria in nature: Where does population variability end and a species start? Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012, 12, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitschwerdt, E.B. Bartonellosis, One Health and all creatures great and small. Vet. Dermatol. 2017, 28, 96-e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regier, Y.; O´rourk, F.; Kempf, V.A.J. Bartonella spp.-a chance to establish One Health concepts in veterinary and human medicine. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguiña, C.; Guerra, H.; Ventosilla, P. Bartonellosis. Clin. Dermatol. 2009, 27, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitschwerdt, E.B. Bartonellosis: One Health Perspectives for an Emerging Infectious Disease. ILAR J. 2014, 55, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saisongkorh, W.; Rolain, J.-M.; Suputtamongkol, Y.; Raoult, D. Emerging Bartonella in humans and animals in Asia and Australia. J. Med Assoc. Thail. Chotmaihet Thangphaet 2009, 92, 707–731. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, S.E.; Chomel, B.B.; Gill, V.A.; Kasten, R.W.; Maggi, R.; Breitschwerdt, E.; Byrne, B.A.; Burek-Huntington, K.A.; Miller, M.A.; Goldstein, T.; et al. Novel Bartonella infection in northern and southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris kenyoni and Enhydra lutris nereis). Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 170, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, K.H.; Harms, C.A.; Cadenas, M.B.; Birkenheuer, A.; Marr, H.S.; Braun-McNeill, J.; Maggi, R.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Bartonella DNA in Loggerhead Sea Turtles. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 949–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, M.Y.; Regnery, R.L.; Kosaya, O.I.; Jones, D.C.; Marston, E.L.; Childs, J.E. Isolation of Bartonella spp. from embryos and neonates of naturally infected rodents. J. Wildl. Dis. 1998, 34, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, R.; Cohen, C.; Flatau, R.; Marcos-Hadad, E.; Garrido, M.; Halle, S.; Nachum-Biala, Y.; Covo, S.; Hawlena, H.; Harrus, S. Untangling the knots: Co-infection and diversity of Bartonella from wild gerbils and their associated fleas. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 4787–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tołkacz, K.; Alsarraf, M.; Kowalec, M.; Dwużnik, D.; Grzybek, M.; Behnke, J.M.; Bajer, A. Bartonella infections in three species of Microtus: Prevalence and genetic diversity, vertical transmission and the effect of concurrent Babesia microti infection on its success. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, L.; Yuan, D.; Guo, L.; Hou, W.; Mo, X.; Yin, J.; Yang, A.; Li, R. Molecular detection of Bartonella in ixodid ticks collected from yaks and plateau pikas (Ochotona curzoniae) in Shiqu County, China. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szekeres, S.; Van Leeuwen, A.D.; Tóth, E.; Majoros, G.; Sprong, H.; Földvári, G. Road-killed mammals provide insight into tick-borne bacterial pathogen communities within urban habitats. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerová, K.; Hönig, V.; Houda, M.; Papežík, P.; Fonville, M.; Sprong, H.; Rudenko, N.; Golovchenko, M.; Černá Bolfíková, B.; Hulva, P.; et al. Hedgehogs, Squirrels, and Blackbirds as Sentinel Hosts for Active Surveillance of Borrelia miyamotoi and Borrelia burgdorferi Complex in Urban and Rural Environments. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiczka, P.M.; Hrazdilová, K.; Majerová, K.; Fonville, M.; Sprong, H.; Hönig, V.; Hofmannová, L.; Papežík, P.; Růžek, D.; Zurek, L.; et al. The Role of Peridomestic Animals in the Eco-Epidemiology of Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, P.; Julliard, R.; Biagianti, S.; Poulle, M.-L. Ecological factors driving the higher hedgehog (Erinaceus europeaus) density in an urban area compared to the adjacent rural area. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 103, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokimäki, J.; Selonen, V.; Lehikoinen, A.; Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L. The role of urban habitats in the abundance of red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris, L.) in Finland. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erizzoli, A.; Esilaghi, C.; Eobiegala, A.; Erudolf, I.; Hubã¡lek, Z.; Fã¶ldvã¡ri, G.; Plantard, O.; Evayssier-Taussat, M.; Bonnet, S.; Spitalska, E.; et al. Ixodes ricinus and Its Transmitted Pathogens in Urban and Peri-Urban Areas in Europe: New Hazards and Relevance for Public Health. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahfari, S.; Ruyts, S.C.; Frazer-Mendelewska, E.; Jaarsma, R.; Verheyen, K.; Sprong, H. Melting pot of tick-borne zoonoses: The European hedgehog contributes to the maintenance of various tick-borne diseases in natural cycles urban and suburban areas. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Kabeya, H.; Hagiya, K.; Kosoy, M.Y.; Une, Y.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Maruyama, S. Multi-locus sequence analysis reveals host specific association between Bartonella washoensis and squirrels. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 148, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bown, K.J.; Ellis, B.A.; Birtles, R.; Durden, L.A.; Lello, J.; Begon, M.; Bennett, M. New world origins for haemoparasites infecting United Kingdom grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), as revealed by phylogenetic analysis of Bartonella infecting squirrel populations in England and the United States. Epidemiol. Infect. 2002, 129, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Maruyama, S.; Kabeya, H.; Hagiya, K.; Izumi, Y.; Une, Y.; Yoshikawa, Y. Exotic Small Mammals as Potential Reservoirs of Zoonotic Bartonella spp. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Loewenich, F.D.; Seckert, C.; Dauber, E.; Kik, M.J.L.; De Vries, A.; Sprong, H.; Buschmann, K.; Aardema, M.L.; Brandstetter, M. Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis with Bartonella washoensis in a Human European Patient and Its Detection in Red Squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 58, 01404–01419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipatova, I.; Razanske, I.; Jurgelevicius, V.; Paulauskas, A. Bartonella washoensis infection in red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) and their ectoparasites in Lithuania. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 68, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitam, I.; Rolain, J.-M.; Kernif, T.; Baziz, B.; Parola, P.; Raoult, D. Bartonella species detected in rodents and hedgehogs from Algeria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitam, I.; Rolain, J.M.; Nicolas, V.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Parola, P.; Gundi, V.A.; Chomel, B.B.; Raoult, D. A multi-gene analysis of diversity of Bartonella detected in fleas from algeria. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 35, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, O.; Gutiérrez, R.; Morick, D.; King, R.; Nachum-Biala, Y.; Baneth, G.; Harrus, S. Detection of Bartonella spp. in wild carnivores, hyraxes, hedgehog and rodents from Israel. Parasitology 2016, 143, 1232–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornok, S.; Foldvari, G.; Rigó, K.; Meli, M.L.; Tóth, M.; Molnár, V.; Gönczi, E.; Farkas, R.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Vector-Borne Agents Detected in Fleas of the Northern White-Breasted Hedgehog. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014, 14, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardosaitė-Busaitienė, D.; Radzijevskaja, J.; Balčiauskas, L.; Bratchikov, M.; Jurgelevičius, V.; Paulauskas, A. Prevalence and diversity of Bartonella species in small rodents from coastal and continental areas. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R.; Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Buffet, J.-P.; Harrus, S. Guidelines for the Isolation, Molecular Detection, and Characterization of Bartonella Species. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, M.; Murray, M.; Gilmore, J.R.D.; Bai, Y.; Gage, K.L. Bartonella Strains from Ground Squirrels Are Identical to Bartonella washoensis Isolated from a Human Patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Probert, W.; Louie, J.K.; Tucker, J.R.; Longoria, R.; Hogue, R.; Moler, S.; Graves, M.; Palmer, H.J.; Cassady, J.; Fritz, C.L. Meningitis Due to a Bartonella washoensis-Like Human Pathogen. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 2332–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osikowicz, L.M.; Billeter, S.A.; Rizzo, M.F.; Rood, M.P.; Freeman, A.N.; Burns, J.E.; Hu, R.; Juieng, P.; Loparev, V.; Kosoy, M. Distribution and Diversity of Bartonella washoensis Strains in Ground Squirrels from California and Their Potential Link to Human Cases. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016, 16, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomel, B.B.; Wey, A.C.; Kasten, R.W. Isolation of Bartonella washoensis from a Dog with Mitral Valve Endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 5327–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemis, D.A.; Kania, S.A. Isolation of Bartonella sp. from Sheep Blood. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1565–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, M.; Bai, Y.; Enscore, R.; Rizzo, M.R.; Bender, S.; Popov, V.; Albayrak, L.; Fofanov, Y.; Chomel, B. Bartonella melophagi in blood of domestic sheep (Ovis aries) and sheep keds (Melophagus ovinus) from the southwestern US: Cultures, genetic characterization, and ecological connections. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 190, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halos, L.; Jamal, T.; Maillard, R.; Girard, B.; Guillot, J.; Chomel, B.; Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Boulouis, H.-J. Role of Hippoboscidae Flies as Potential Vectors of Bartonella spp. Infecting Wild and Domestic Ruminants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 6302–6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumsa, B.; Parola, P.; Raoult, D.; Socolovschi, C. Bartonella melophagi in Melophagus ovinus (sheep ked) collected from sheep in northern Oromia, Ethiopia. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 37, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, I.; Betášová, L.; Bischof, V.; Venclíková, K.; Blažejová, H.; Mendel, J.; Hubálek, Z.; Kosoy, M. Molecular survey of arthropod-borne pathogens in sheep keds (Melophagus ovinus), Central Europe. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 3679–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, B.; Li, F.; Li, K.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, L. Molecular Identification of Bartonella melophagi and Wolbachia Supergroup F from Sheep Keds in Xinjiang, China. Korean J. Parasitol. 2018, 56, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucheikhchoukh, M.; Mechouk, N.; Benakhla, A.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P. Molecular evidence of bacteria in Melophagus ovinus sheep keds and Hippobosca equina forest flies collected from sheep and horses in northeastern Algeria. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 65, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R.; Kosoy, M.; Mintzer, M.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Isolation of Candidatus Bartonella melophagi from Human Blood1. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izenour, K.; Zikeli, S.; Kalalah, A.; Ditchkoff, S.S.; Starkey, L.A.; Wang, C.; Zohdy, S. Diverse Bartonella spp. detected in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and associated keds (Lipoptena mazamae) in the southeastern USA. J. Wildl. Dis. 2020, 56, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Salzburger, W.; Liesch, M.; Chang, C.-C.; Maruyama, S.; Lanz, C.; Calteau, A.; Lajus, A.; Médigue, C.; Schuster, S.C.; et al. Parallel Evolution of a Type IV Secretion System in Radiating Lineages of the Host-Restricted Bacterial Pathogen Bartonella. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremeeva, M.E.; Gerns, H.L.; Lydy, S.L.; Goo, J.S.; Ryan, E.T.; Mathew, S.S.; Ferraro, M.J.; Holden, J.M.; Nicholson, W.L.; Dasch, G.A.; et al. Bacteremia, Fever, and Splenomegaly Caused by a Newly Recognized Bartonella Species. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2381–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujica, G.M.; León, D.F.; Espinoza-Culupú, A. Identificación de Bartonella rochalimae en un Brote de Enfermedad de Carrión Mediante Caracterización Molecular del Gen 16S rRNA. In Proceedings of the VIII Congreso Internacional del Instituto Nacional de Salud, Lima, Peru, 6 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami, M.; Sato, S.; Nabeshima, K.; Kabeya, H.; Ueda, D.; Suzuki, K.; Maruyama, S. Molecular survey of Bartonella rochalimae in Japanese raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinus). J. Wildl. Dis. 2020, 56, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, J.B.; Gabriel, M.W.; Kasten, R.W.; Brown, R.N.; Theis, J.H.; Foley, J.E.; Chomel, B.B. Gray Foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) as a Potential Reservoir of a Bartonella clarridgeiae-Like Bacterium and Domestic Dogs as Part of a Sentinel System for Surveillance of Zoonotic Arthropod-Borne Pathogens in Northern California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, J.D.; Kasten, R.W.; Coonan, T.J.; Clifford, D.L.; Chomel, B.B. Isolation or detection of Bartonella vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii and Bartonella rochalimae in the endangered island foxes (Urocyon littoralis). Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 154, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrikagoitia, X.; Gil, H.; García-Esteban, C.; Anda, P.; Juste, R.A.; Barral, M. Presence of Bartonella Species in Wild Carnivores of Northern Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 78, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, J.B.; Gabriel, M.W.; Kasten, R.W.; Brown, R.N.; Koehler, J.E.; Macdonald, K.A.; Kittleson, M.D.; Thomas, W.P.; Chomel, B.B. Infective Endocarditis in a Dog and the Phylogenetic Relationship of the Associated Bartonella rochalimae strain with isolates from dogs, gray foxes, and a human. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henn, J.B.; Chomel, B.B.; Boulouis, H.-J.; Kasten, R.W.; Murray, W.J.; Bar-Gal, G.K.; King, R.; Courreau, J.-F.; Baneth, G. Bartonella rochalimaein Raccoons, Coyotes, and Red Foxes. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1984–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Gilbert, A.; Fox, K.; Osikowicz, L.; Kosoy, M. Bartonella rochalimae and B. Vinsonii subsp. Berkhoffii in wild carnivores from Colorado, USA. J. Wildl. Dis. 2016, 52, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E.; Qurollo, B.; Olech, C.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Bartonella rochalimae, a newly recognized pathogen in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, W.-C.; Chomel, B.B.; Chang, C.-C. Isolation of Bartonella species from rodents in Taiwan including a strain closely related to ‘Bartonella rochalimae’ from Rattus norvegicus. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 57, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saisongkorh, W.; Wootta, W.; Sawanpanyalert, P.; Raoult, D.; Rolain, J.-M. “Candidatus Bartonella thailandensis”: A new genotype of Bartonella identified from rodents. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 139, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gundi, V.A.K.B.; Kosoy, M.Y.; Myint, K.S.A.; Shrestha, S.K.; Shrestha, M.P.; Pavlin, J.A.; Gibbons, R.V. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Bartonella Species Detected in Different Tissues of Small Mammals in Nepal. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 8247–8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipatova, I.; Paulauskas, A.; Puraite, I.; Radzijevskaja, J.; Balciauskas, L.; Gedminas, V. Bartonella infection in small mammals and their ectoparasites in Lithuania. Microbes Infect. 2015, 17, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.F.; Osikowicz, L.; Cáceres, A.G.; Luna-Caipo, V.D.; Suarez-Puyen, S.M.; Bai, Y.; Kosoy, M. Identification of Bartonella rochalimae in Guinea Pigs (Cavia porcellus) and Fleas Collected from Rural Peruvian Households. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Yanes, E.; Abreu-Acosta, N.; Izquierdo-Rodriguez, E.; Martin-Carrillo, N.; Foronda, P. Bartonella species and haplotypes in rodents and their fleas in Lanzarote and El Hierro in the Canary Islands, Spain. J. Vector Ecol. 2020, 45, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.G.; Rozental, T.; Guterres, A.; Teixeira, B.R.; Andrade-Silva, B.E.; da Costa-Neto, S.F.; Furtado, M.C.; Moratelli, R.; D’Andrea, P.S.; Lemos, E.R.S. Investigation of Bartonella spp. in brazilian mammals with emphasis on rodents and bats from the Atlantic Forest. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2020, 13, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Gutiérrez, R.; Seguel, M.; Monti, G.; Otth, C.; Bittencourt, P.; Sepúlveda, P.; Alabí, A.; Nachum-Biala, Y.; Harrus, S. Molecular survey of Bartonella spp. in rodents and fleas from Chile. Acta Trop. 2020, 212, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staggemeier, R.; Venker, C.A.; Klein, D.H.; Petry, M.; Spilki, F.; Cantarelli, V.V. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae in cats in the south of Brazil: A molecular study. Memórias do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2010, 105, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, M.R.; Canola, R.A.M.; Braz, J.B.; Perossi, I.F.S.; Calchi, A.C.; Ikeda, P.; Machado, R.Z.; Vasconcelos, R.D.O.; Camacho, A.A. Aortic valve endocarditis due to Bartonella clarridgeiae in a dog in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Veterinária 2019, 28, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, M.; Mills, J.N.; Mcgill, S.; Benjamin, G.; Ellis, B.A. Bartonella infection in sylvatic small mammals of central Sweden. Epidemiol. Infect. 2003, 130, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tea, A.; Alexiou-Daniel, S.; Papoutsi, A.; Papa, A.; Antoniadis, A. Bartonella Species Isolated from Rodents, Greece. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 963–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Scola, B.; Zeaiter, Z.; Khamis, A.; Raoult, D. Gene-sequence-based criteria for species definition in bacteriology: The Bartonella paradigm. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Kabeya, H.; Kosoy, M.Y.; Bai, Y.; Smirnov, G.; McColl, D.; Artsob, H.; Maruyama, S. Evolutional and Geographical Relationships of Bartonella grahamii Isolates from Wild Rodents by Multi-locus Sequencing Analysis. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 57, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, E.C.; Ellegaard, K.; Granberg, F.; Xie, Z.; Maruyama, S.; Kosoy, M.Y.; Birtles, R.; Andersson, S.G.E. Rapid diversification by recombination in Bartonella grahamii from wild rodents in Asia contrasts with low levels of genomic divergence in Northern Europe and America. Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 2241–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksi, J.; Rantala, S.; Kilpinen, S.; Silvennoinen, R.; Vornanen, M.; Veikkolainen, V.; Eerola, E.; Pulliainen, A.T. Cat Scratch Disease Caused by Bartonella grahamii in an Immunocompromised Patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 2781–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.; Li, S.; Lu, L.; Wang, R.; Song, X.; Sun, K.; Shi, Y.; Li, D.; Yu, J. Genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.H.; Bai, Y.; Malania, L.; Winchell, J.M.; Kosoy, M.Y. Development of a Novel Genus-Specific Real-Time PCR Assay for Detection and Differentiation of Bartonella Species and Genotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1645–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtles, R.; Raoult, D. Comparison of Partial Citrate Synthase Gene (gltA) Sequences for Phylogenetic Analysis of Bartonella Species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1996, 46, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeter, S.A.; Gundi, V.A.K.B.; Rood, M.P.; Kosoy, M.Y. Molecular Detection and Identification of Bartonella Species in Xenopsylla cheopis Fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) Collected from Rattus norvegicus Rats in Los Angeles, California. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 7850–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofer, S.; Gutiérrez, R.; Morick, D.; Mumcuoglu, K.Y.; Harrus, S. Molecular detection of zoonotic bartonellae (B. henselae, B. elizabethae and B. rochalimae) in fleas collected from dogs in Israel. Med. Vet. Èntomol. 2015, 29, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, A.F.; Regnery, R.; Jameson, P.; Greene, C.; Krause, D.C. Differentiation of Bartonella-like isolates at the species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism in the citrate synthase gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 1797–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renesto, P.; Gouvernet, J.; Drancourt, M.; Roux, V.; Raoult, D. Use of rpoB Gene Analysis for Detection and Identification of Bartonella Species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paziewska, A.; Harris, P.D.; Zwolińska, L.; Bajer, A.; Siński, E. Recombination Within and Between Species of the Alpha Proteobacterium Bartonella Infecting Rodents. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 61, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R.G.; Breitschwerdt, E. Potential Limitations of the 16S-23S rRNA Intergenic Region for Molecular Detection of Bartonella Species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Locus | PCR Type | Primer Name | Sequence 5′–3′ | References | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gltA | PCR gltA-1 | 443f | GCTATGTCTGCATTCTATCA | [81] | 750 |

| 1210R | GATCYTCAATCATTTCTTTCCA | [82] | |||

| nested PCR gltA-1 | 443f | GCTATGTCTGCATTCTATCA | [81] | 340 | |

| 781R | CCACCATGAGCTGGTCCCC | [83] | |||

| PCR gltA-2 | Bhcs.781p fwd | GGGGACCAGCTCATGGTGG | [84] | 370 | |

| Bhcs.1137n rev | AATGCAAAAAGAACAGTAAACA | ||||

| PCR * | BwgltAf | AATCAATCCAGTGCTTACTCG | [31] | 625 | |

| BwgltAr | CTGCATAGCCTGTATAGAGTT | ||||

| rpoB | PCR | 1400F | CGCATTGGCTTACTTCGTATG | [85] | 800 |

| 2300R | GTAGACTGATTAGAACGCTG | ||||

| nested PCR | 1596F | CGCATTATGGTCGTATTTGTCC | [86] | 400 | |

| 2300R | GTAGACTGATTAGAACGCTG | [85] | |||

| ftsZ | PCR ** | F | CATATGGTTTTCATTACTGCYGGTATGG | [86] | 515 |

| R | TTCTTCGCGAATACGATTAGCAGCTTC | ||||

| ITS | PCR | H56s | GGGGAACCTGTGGCTGGATCAC | [87] | 900–1100 |

| 983as | TGTTCTYACAACAATGATGATG | ||||

| nested PCR | H493as | TGAACCTCCGACCTCACGCTTATC | [87] | 200–300 | |

| 321s | AGATGATGATCCCAAGCCTTCTGG |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majerová, K.; Gutiérrez, R.; Fonville, M.; Hönig, V.; Papežík, P.; Hofmannová, L.; Lesiczka, P.M.; Nachum-Biala, Y.; Růžek, D.; Sprong, H.; et al. Hedgehogs and Squirrels as Hosts of Zoonotic Bartonella Species. Pathogens 2021, 10, 686. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10060686

Majerová K, Gutiérrez R, Fonville M, Hönig V, Papežík P, Hofmannová L, Lesiczka PM, Nachum-Biala Y, Růžek D, Sprong H, et al. Hedgehogs and Squirrels as Hosts of Zoonotic Bartonella Species. Pathogens. 2021; 10(6):686. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10060686

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajerová, Karolina, Ricardo Gutiérrez, Manoj Fonville, Václav Hönig, Petr Papežík, Lada Hofmannová, Paulina Maria Lesiczka, Yaarit Nachum-Biala, Daniel Růžek, Hein Sprong, and et al. 2021. "Hedgehogs and Squirrels as Hosts of Zoonotic Bartonella Species" Pathogens 10, no. 6: 686. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10060686

APA StyleMajerová, K., Gutiérrez, R., Fonville, M., Hönig, V., Papežík, P., Hofmannová, L., Lesiczka, P. M., Nachum-Biala, Y., Růžek, D., Sprong, H., Harrus, S., Modrý, D., & Votýpka, J. (2021). Hedgehogs and Squirrels as Hosts of Zoonotic Bartonella Species. Pathogens, 10(6), 686. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10060686