Language Vitality of Spanish in Equatorial Guinea: Language Use and Attitudes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

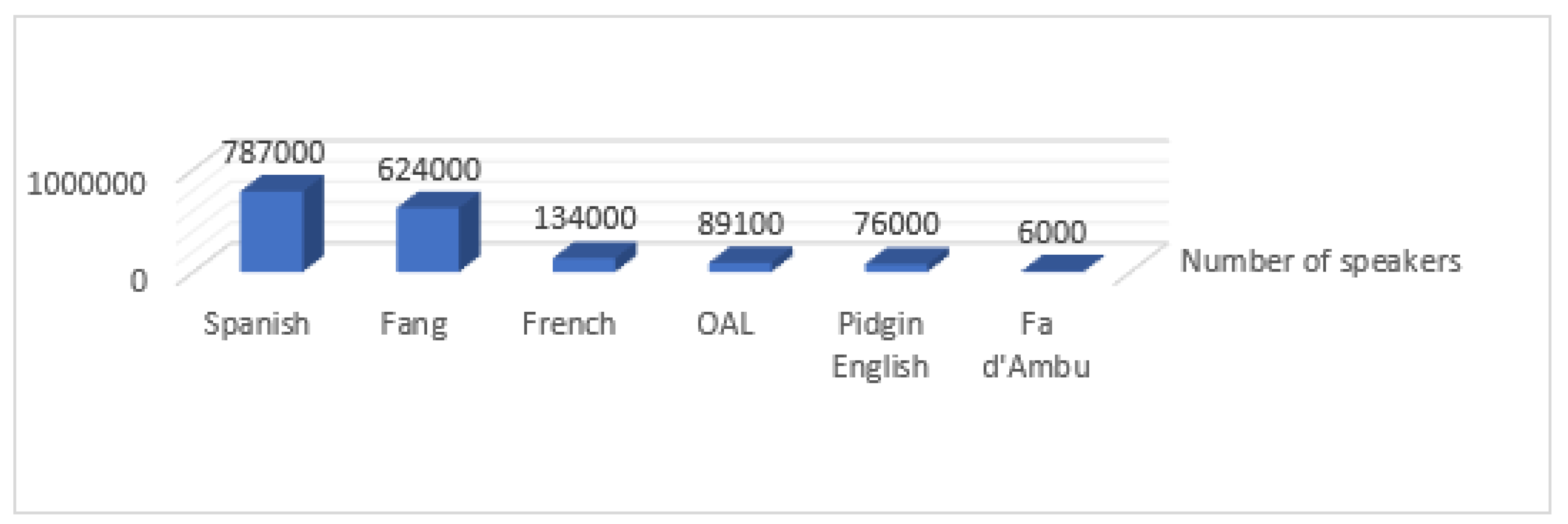

Linguistic Situation

2. Language Vitality of Spanish

- (1)

- students attending college tend to speak their native language at home, instead of Spanish

- (2)

- teachers do not have the requisite professional training or a solid competence in the Spanish language

- (3)

- the education system faces many deficiencies related to personnel, teaching materials and other important logistics

- (4)

- the population has not cultivated the habit of reading and there is a scarcity of bookstores

3. Equatorial Guinean Spanish

- (1)

- an occlusive articulation of /b/, /d/, /g/

- (2)

- the retention of the final /s/ of a syllable or word

- (3)

- the interchangeable use of interdental consonant /θ/ common in Peninsular Spanish and /s/ common in the Spanish varieties of Hispanic America

- (4)

- the neutralization of tap /r/ and trill /rr/

- (5)

- the conjugations of the verbs in pronouns tú and usted forms are used interchangeably

- (6)

- the lack of distinction between the use of ustedes and vosotros

- (7)

- the predominant use of the preposition en with motion verbs

- (8)

- its most distinctive characteristic, the use of alternating phonology tone on each syllable, an influence of the autochthonous Bantu languages

Language Attitudes towards Equatoguinean Spanish

4. Pilot Study

- How widespread is the use of Spanish in Equatorial Guinea?

- What are the attitudes of citizens towards Equatorial Guinean Spanish?

4.1. Previous Studies

4.2. Material and Methods

4.2.1. Respondents

4.2.2. Procedure

4.2.3. Questionnaire

- Language history (response type: short answer)

- Individual language use and choice (response type: multiple-choice)

- Societal language use (single choice)

- Language beliefs and opinions (7-point Likert scale)

- Evaluations of Equatorial Guinean Spanish (semantic differentiation scale/7-point Likert scale)

- Demographic characteristics

4.3. Results

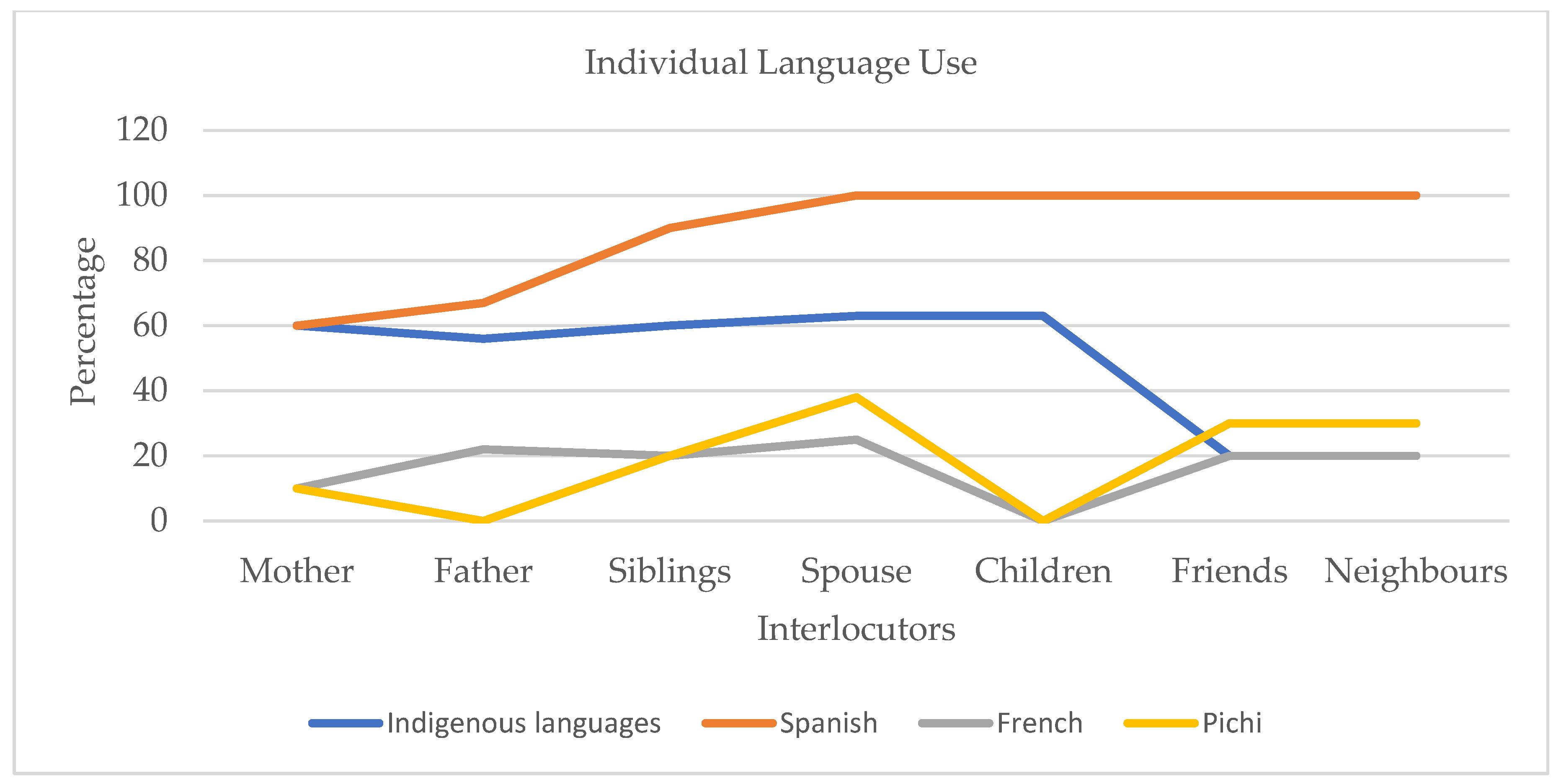

4.3.1. Individual Spanish Usage

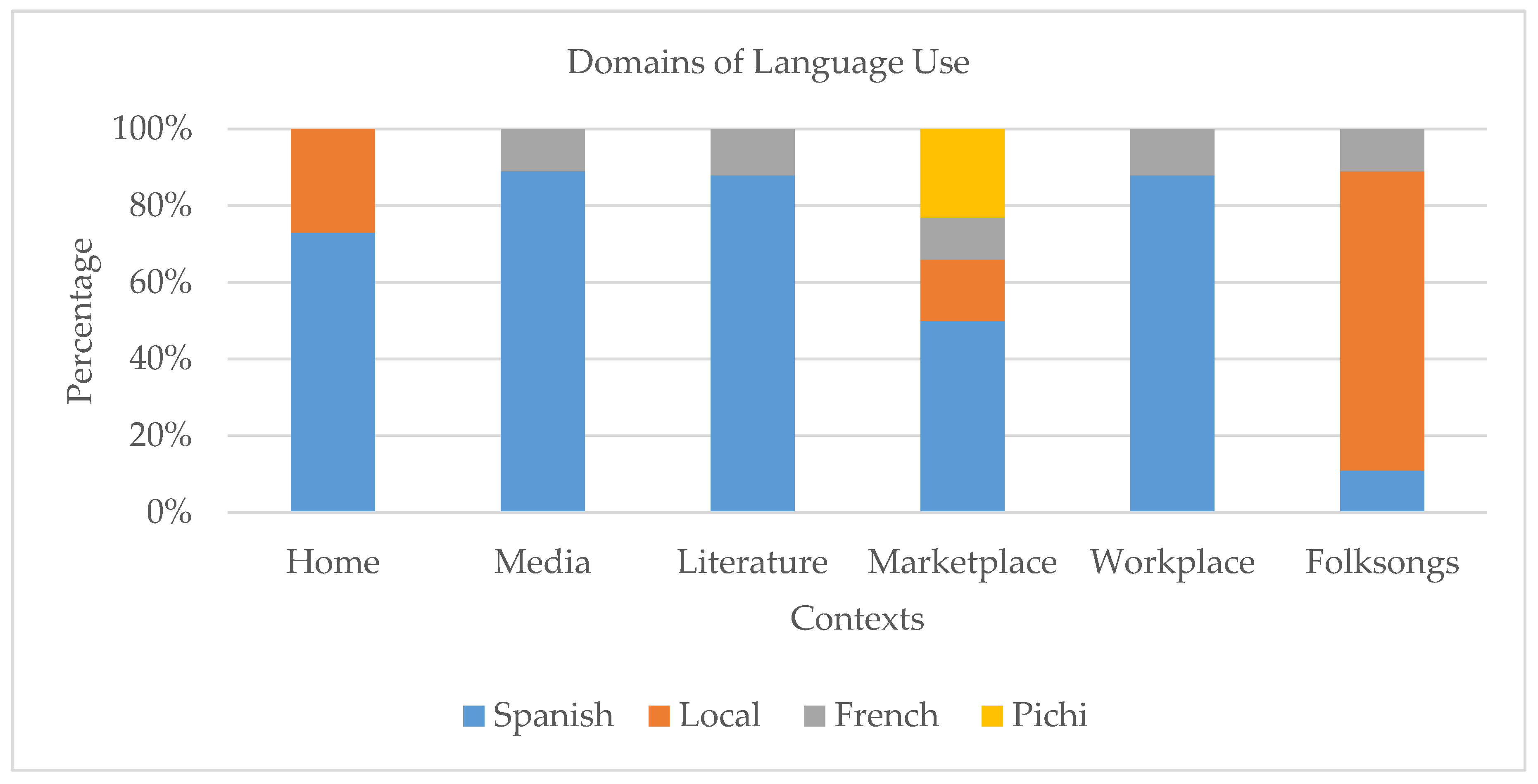

4.3.2. Spanish Use in Society

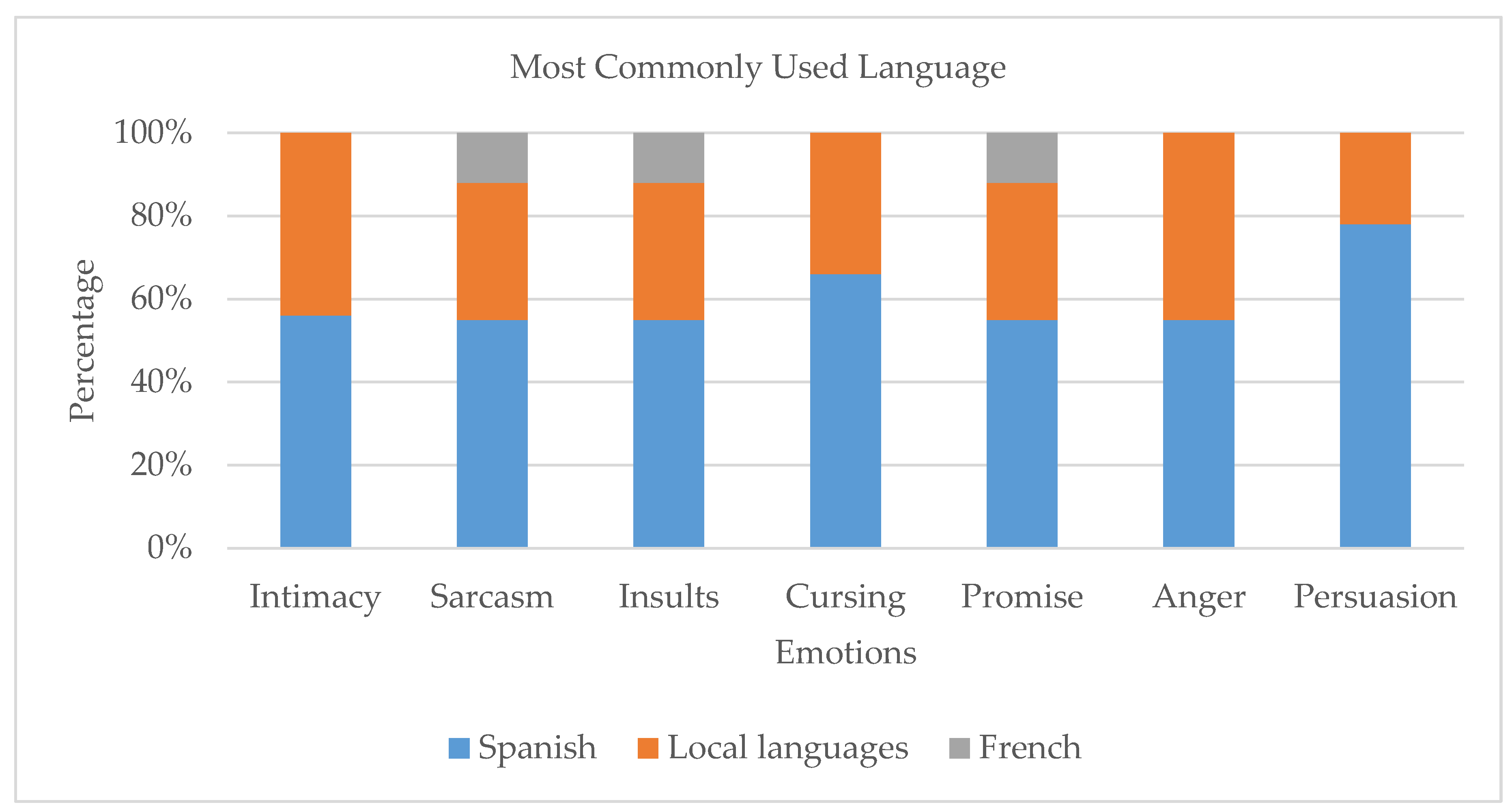

4.3.3. Opinions/Attitudes towards Spanish

4.3.4. Notions about Equatorial Guinean Spanish

4.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- ¿Qué idioma aprendió usted primero (es decir su primer idioma)?

- ¿Habla Ud. este idioma frecuentemente?

- ¿Puede Ud. mantener una conversación en su primer idioma?

- ¿Puede Ud. discutir o tratar asuntos de la universidad/del trabajo en ese idioma?

- ¿Qué otros idiomas habla Ud.?

- ¿Alterna Ud. entre dos o tres idiomas en una conversación?

- ¿Ha vivido en Guinea Ecuatorial desde su niñez?

- ¿Ha vivido en otro país hispanohablante? ¿Dónde? ¿Y por cuánto tiempo?

- ¿Qué idioma(s) habla su madre?

- ¿Qué idioma(s) habla su padre?

- Con su esposo/a

- Con su esposo/a enfrente de sus niños

- Con sus niños

- Con sus padres

- Con sus hermanos

- Con su(s) empleado(s)

- Con su jefe

- Con amigos en su vecindario

- Con amigos en el centro

- Con sus vecinos

- Con sus profesores

- Con el médico

- Con el curandero

- Con el padre o cura

- Con su compañero de trabajo

- En casa

- En una tienda

- En transmisión de radio

- En la transmisión de televisión

- En periódicos

- Para chismes

- En una clase universitaria

- En una clase en colegio o instituto

- En una clase primaria

- Para expresar sarcasmo

- En los documentos escritos para la enseñanza

- Para discutir sus estudios con otros estudiantes

- Para discutir sus estudios con profesores

- Para escribir literatura (novelas, obras de ficción y no ficción)

- Para dar mandatos militares

- Para jurar

- En el mercado

- Para regatear

- En el banco financiero

- En la comisaría de policía

- Para contar chistes

- En una ceremonia religiosa

- En las instituciones gubernamentales

- Para insultar

- En los tribunales

- Para maldecir

- Para decir cosas intimas

- En las canciones folclóricas

- Para hablar con bebés

- Para persuadir a alguien

- El español es importante para la identidad de Guinea Ecuatorial

- Es más fácil escribir español que mi lengua materna

- Es más fácil hablar mi lengua materna que el español

- Me gusta hablar español

- El español guineano es un dialecto como cualquier otro en América del Sur o España

- Los guineanos hablan bien el español

- Es importante que los guineanos aprendan y hablen bien el español

- Recomiendo Guinea Ecuatorial como un foco para aprender el español en África

- El español es la lengua más hablada en Guinea Ecuatorial.

- El nivel del español guineano es bajo.

- Íntimo

- Preciso

- Musical

- Rico

- Sofisticado

- Rítmico

- Bonito

- Superior

- Puro

- Sagrado

- Refinado

- Relajante

- Elegante

- Agradable al oído

- Lógico

- Encantador

- Colorido

- Persuasivo

- Afectuoso

- Gracioso

- ¿Cuál es su sexo?

- ¿Cuál es su edad?

- ¿Cuál es su nivel de educación (o el último curso que ha terminado)?

- ¿Cuál es su ocupación?

- ¿Cuál es su país natal?

- ¿Cuál es su etnia?

- ¿En qué comuna/ciudad vive usted?

- ¿En qué ciudad ha pasado más años?

References

- Abrams, Jessica R., Valerie Barker, and Howard Giles. 2009. An Examination of the Validity of the Subjective Vitality Questionnaire. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 30: 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela G. 2003. Miami Cuban perceptions of varieties of Spanish. In Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology. Edited by Daniel Long and Dennis R. Preston. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 2, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- ASALE. 2015. La Academia Ecuatoguineana solicita su ingreso en la ASALE. Noticias de la ASALE. November 24. Available online: http://www.asale.org/noticias/la-academia-ecuatoguineana-solicita-su-ingreso-en-la-asale (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Baker, Colin. 2006. Endangered languages: Planning and revitalization. In Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 5th ed. Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters, pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Allan. 2014. The Guidebook to Sociolinguistics, 1st ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bibang Oyee, Julián. 2002. El Español Guineano—Interferencias, Guineanismos. Malabo: Julián Bibang Oyee. [Google Scholar]

- Bolekia Boleká, Justo. 2005. Panorama de la literatura en español en Guinea Ecuatorial. In El Español en el Mundo: Anuario del Instituto Cervantes 2005. Barcelona and Madrid: Instituto Cervantes, pp. 97–152. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Barril, Manuel. 1966. La Influencia de Las Lenguas Nativas en el Español de la Guinea Ecuatorial. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Chirilă, Elena Magdalena. 2015. Identidad Lingüística en Guinea Ecuatorial: Diglosia y Actitudes Lingüísticas ante el Español. Master’s dissertation, Universitat Bergensis, Bergen, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Jinny K. 2005. Bilingualism in Paraguay: Forty Years after Rubin’s Study. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 26: 233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Robert L., and Joshua A. Fishman. 1977. A Study of Language Attitudes. Bilingual Review/La Revista Bilingüe 4: 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, David. 1992. An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Language and Languages. Cambridge: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Granda Gutiérrez, Germán. 1984. Perfil lingüístico de Guinea Ecuatorial. In Homenaje a Luis Flórez: Estudios de Historia Cultural, Dialectología, Geografía Lingüística, Sociolingüística, Fonética, Gramática y Lexicografía. Bogotá: Instituto Caro y Cuervo, pp. 119–95. [Google Scholar]

- Granda Gutiérrez, Germán. 1988. El Español en el África Subsahariana. África 2000: Revista de Cultura 7: 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Esling, John H. 1998. Everyone has an accent except me. In Language Myths. Edited by Laurie Bauer and Peter Trudgill. London: Penguin Books, pp. 169–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Joshua A. 1991. Reversing Language Shift. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard. 2001. Ethnolinguistic vitality. In Concise Encyclopedia of Sociolinguistics. Edited by Rajend Masthrie. Oxford: Elsevier Science, pp. 472–73. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, Richard Y. Bourhis, and Donald M. Taylor. 1977. Towards a theory of language in ethnic group relations. In Language, Ethnicity and Intergroup Relations. Edited by Howard Giles. London: Academic Press, pp. 307–48. [Google Scholar]

- González Echegaray, Carlos. 1951. Notas sobre el Español en África Ecuatorial. Revista de Filología Española 35: 106–18. [Google Scholar]

- González Echegaray, Carlos. 1959. Estudios Guineos. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Granados, Vicente. 1986. Guinea: Del ‘Falar Guinéu’ al Español Ecuatoguineano. Epos 2: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, Laura C. 1999. A view from the West: Perceptions of U. S. dialects by Oregon residents. In Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology. Edited by Dennis R. Preston. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 1, pp. 315–32. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Janet. 2013. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, 4th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger, Nancy H., and Serafín M. Coronel-Molina. 2004. Quechua Language Shift, Maintenance and Revitalization in the Andes: The Case for Language Planning. International Sociology of Language 167: 9–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Guinea Ecuatorial 2015. Censo de Población 2015—República de Guinea Ecuatorial. Available online: http://www.inege.gq/ (accessed on 2 May 2018).

- Jarvis, Scott, and Aneta Pavlenko. 2008. Crosslinguistic Influence in Language and Cognition. New York: Routledge, New York: Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Larre Muñoz, Mikel. 2013. La situación del español en Guinea Ecuatorial: Diagnóstico y Tratamiento. Humanitas. Available online: http://humanitasguineae.blogspot.com/2013/06/la-situacion-del-espanol-en-guinea.html (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Lewis, M. Paul, and Gary F. Simons. 2010. Assessing Endangerment: Expanding Fishman’s GIDS. Revue Roumaine de Linguistique (RRL) 2: 103–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ley Fundamental de Guinea Ecuatorial. 2012. Available online: http://www.droit-afrique.com/upload/doc/guinee-equatoriale/GE-Constitution-2012-ESP.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2018).

- Lipski, John M. 1985. The Spanish of Equatorial Guinea: The Dialect of Malabo and Its Implications for Spanish Dialectology. Beihefte Zur Zeitschrift Für Romanische Philologie, Bd. 209. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John M. 2000. The Spanish of Equatorial Guinea: Research on La Hispanidad’s Best-Kept Secret. Afro-Hispanic Review 19: 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John M. 2004. The Spanish Language of Equatorial Guinea. Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies 8: 115–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipski, John M. 2008. El español de Guinea Ecuatorial en el contexto del español mundial. In La Situación Actual en el Español en África: Actas del II Congreso Internacional de Hispanistas en África. Edited by Gloria Nistal and Guillermo Pié Jahn. Madrid: SIAL Ediciones, pp. 79–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John M. 2014. ¿Existe un Dialecto “Ecuatoguineano” del Español? Revista Iberoamericana 80: 865–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso Luengo, Antonio J., and Julián B. Bibang Oyee. 2014. El español en Guinea Ecuatorial. In La enseñanza del español en África Subsahariana. Edited by Javier Serrano Avilés. Madrid: Instituto Cervantes, Available online: https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/eeas/capitulo13.htm (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Mohamadou, Aminou. 2008. Acercamiento al “Espaguifrangles”, El Español Funcional de Guinea Ecuatorial. CAUCE, Revista Internacional de Filología y su Didáctica 31: 213–29. [Google Scholar]

- Morgades Besari, Trinidad. 2005. Breve apunte sobre el español en Guinea Ecuatorial. In El Español en el Mundo:Anuario del Instituto Cervantes 2005. Madrid: Instituto Cervantes, pp. 255–62. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo, José. 2011. El Español Agoniza en Guinea Ecuatorial. Guin Guin Bali. Available online: http://www.guinguinbali.com/index.php?lang=es&mod=news&cat=4&id=2424 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Nguendjo Tiogang, Issacar. 2015. Las Cuestiones del Género y del Número de los Neologismos Léxicos en el Español de Guinea Ecuatorial. Tonos Digital 28: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nistal Rosique, Gloria. 2007. El caso del español en Guinea Ecuatorial. In El Español en el Mundo: Anuario del Instituto Cervantes 2007. Madrid: Instituto Cervantes, pp. 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nsue Otong, Carlos. 1986. Guineanismos o Español de Guinea Ecuatorial. Muntu 4–5: 265–68. [Google Scholar]

- Obiang, Teodoro. 2001. Inaugural Speech Presented at the II Congreso Internacional de la Lengua Española. Valladolid. Available online: http://congresosdelalengua.es/valladolid/inauguracion/obiang_t.htm (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Preston, Dennis R. 2010. Language, People, Salience, Space: Perceptual Dialectology and Language Regard. Dialectology 5: 87–131. [Google Scholar]

- Proyecto de Ley Constitucional. 2010. Available online: https://www.guineaecuatorialpress.com/imgdb/2010/20-7-2010Decretosobreelportuguescomoidiomaoficial.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Quilis, Antonio. 1983. Actitud de los Ecuatoguineanos ante la Lengua Española. LEA: Lingüística Española Actual 5: 269–75. [Google Scholar]

- Quilis, Antonio. 1988. Nuevos Datos sobre la Actitud de los Ecuatoguineanos ante la Lengua Español. Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 36: 719–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilis, Antonio. 1992. La Lengua Española en Cuatro Mundos. Madrid: Editiorial MAPFRE. [Google Scholar]

- Quilis, Antonio, and Celia Casado-Fresnillo. 1992. Fonología y Fonética de la Lengua Española Hablada en Guinea Ecuatorial. Revue de Linguistique Romane 56: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilis, Antonio, and Celia Casado-Fresnillo. 1995. La Lengua Española en Guinea Ecuatorial. Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Joan. 1974. Bilingüismo Nacional en el Paraguay. México: Instituto Indigenista Interamericano. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Martínez, Ana María. 2002. La enseñanza del español como lengua extranjera en Guinea Ecuatorial y la interferencia de las lenguas indígenas. In Actas XIII de la ASELE. El Español, Lengua del Mestizaje y la Interculturalidad. Edited by José Coloma Maestre and Manuel Pérez Gutiérrez. Murcia: ASELE, vol. 13, pp. 762–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schlumpf, Sandra. 2016. Hacia el Reconocimiento del Español de Guinea Ecuatorial. Estudios de Lingüística del Español 37: 217–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sikota, Ndjoli. 2009. Cervantes en África—Parte 2. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=14sKmYtKbIQ (accessed on 1 May 2018).

- Simons, Gary F., and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2018. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 21st ed. Dallas: SIL International, Available online: http://www.ethnologue.com (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Tararova, Olga. 2017. Language is Me. Language Maintenance in Chipilo, Mexico. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 248: 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, Sarah G. 2001. Language Contact: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2003. Language Vitality and Endangerment. UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/pdf/Language_vitality_and_endangerment_EN.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2018).

| Language | Locations | Speakers (Total) |

|---|---|---|

| Spanish | Widespread | 787,000 |

| French | Major cities | 134,000 |

| Portuguese | ND | ND |

| Pidgin English | Bioko Norte and Bioko Sur provinces | 76,000 |

| Fang | Continental Equatorial Guinea | 624,000 |

| Fa d’Ambu | Annobón province | 6000 |

| Ndowe | Litoral province | 9200 |

| Bujeba | Litoral province | 13,000 |

| Baseke | Litoral province | 11,000 |

| Benga | Litoral province | 4000 |

| Bube | Bioko Norte and Bioko Sur provinces | 51,000 |

| Balengue | Litoral province | 900 |

| Age (Years) | |

| 18–24 | 3 |

| 25–34 | 4 |

| 35–44 | 2 |

| 45–54 | 1 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 |

| Female | 3 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Annobones | 1 |

| Bubi | 2 |

| Fang | 6 |

| Fang-Annobones | 1 |

| Mother Tongue | |

| Fa dambo | 1 |

| Bubi | 2 |

| Fang | 3 |

| Spanish | 4 |

| Languages Spoken | |

| Spanish | 10 |

| French | 8 |

| Local languages | 6 |

| Portuguese | 1 |

| Pichi | 5 |

| Other (English, Turkish, Catalan) | 4 |

| Academic Level | |

| Finished high school | 1 |

| Finished Polytechnic | 1 |

| Finished University | 2 |

| In University | 5 |

| In Graduate School | 1 |

| Occupation | |

| Student | 5 |

| Doctor | 1 |

| Office worker | 1 |

| Technician | 1 |

| Businessman | 1 |

| Civil servant | 1 |

| Statements | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Spanish is important to the identity of Equatorial Guinea | 5.6 | 0.8 |

| 2. It is easier to write Spanish than my mother tongue | 6.4 | 0.8 |

| 3. It is easier to speak my mother tongue than Spanish | 4.9 | 1.6 |

| 4. I like speaking Spanish | 6.8 | 0.4 |

| 5. Equatorial Guinean Spanish is a dialect like any other in South America or Spain | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| 6. Guineans speak Spanish well | 4.3 | 1.6 |

| 7. It is important that Guineans learn and speak Spanish well | 6.9 | 0.3 |

| 8. I recommend Equatorial Guinea as a centre for learning Spanish in Africa | 6.6 | 0.7 |

| 9. Spanish is the most spoken language in Equatorial Guinea | 6.7 | 0.5 |

| 10. The standard of Guinean Spanish is low | 4.3 | 2.0 |

| Adjectives | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| Intimate | 3.6 | 2.1 |

| Precise | 4.5 | 1.8 |

| Musical | 4.4 | 1.7 |

| Rich | 3.9 | 1.4 |

| Sophisticated | 4.3 | 1.6 |

| Rhythmical | 4.4 | 1.5 |

| Beautiful | 4.6 | 1.5 |

| Superior | 3.9 | 1.6 |

| Pure | 4.5 | 1.3 |

| Sacred | 4.0 | 2.1 |

| Refined | 4.5 | 1.1 |

| Relaxing | 4.0 | 1.3 |

| Elegant | 3.9 | 1.7 |

| Pleasing to the ear | 4.0 | 1.8 |

| Logical | 4.9 | 0.8 |

| Charming | 4.4 | 1.2 |

| Colourful | 4.5 | 1.3 |

| Persuasive | 4.5 | 1.6 |

| Affectionate | 4.9 | 0.6 |

| Funny | 5.9 | 0.8 |

| Average | 4.4 | 1.5 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomashie, G.A. Language Vitality of Spanish in Equatorial Guinea: Language Use and Attitudes. Humanities 2019, 8, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010033

Gomashie GA. Language Vitality of Spanish in Equatorial Guinea: Language Use and Attitudes. Humanities. 2019; 8(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomashie, Grace A. 2019. "Language Vitality of Spanish in Equatorial Guinea: Language Use and Attitudes" Humanities 8, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010033

APA StyleGomashie, G. A. (2019). Language Vitality of Spanish in Equatorial Guinea: Language Use and Attitudes. Humanities, 8(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010033