A Proposal for Afro-Hispanic Peoples and Culture as General Studies Course in African Universities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Afro-Hispanics and Mestizaje Ideology

2.1. Consequences of Mestizaje on the Visibility of Afro-Hispanics

2.2. Creating Visibility through Curriculum Inclusion

3. Nigerian Peoples and Culture as a General Studies Course in Nigerian Universities

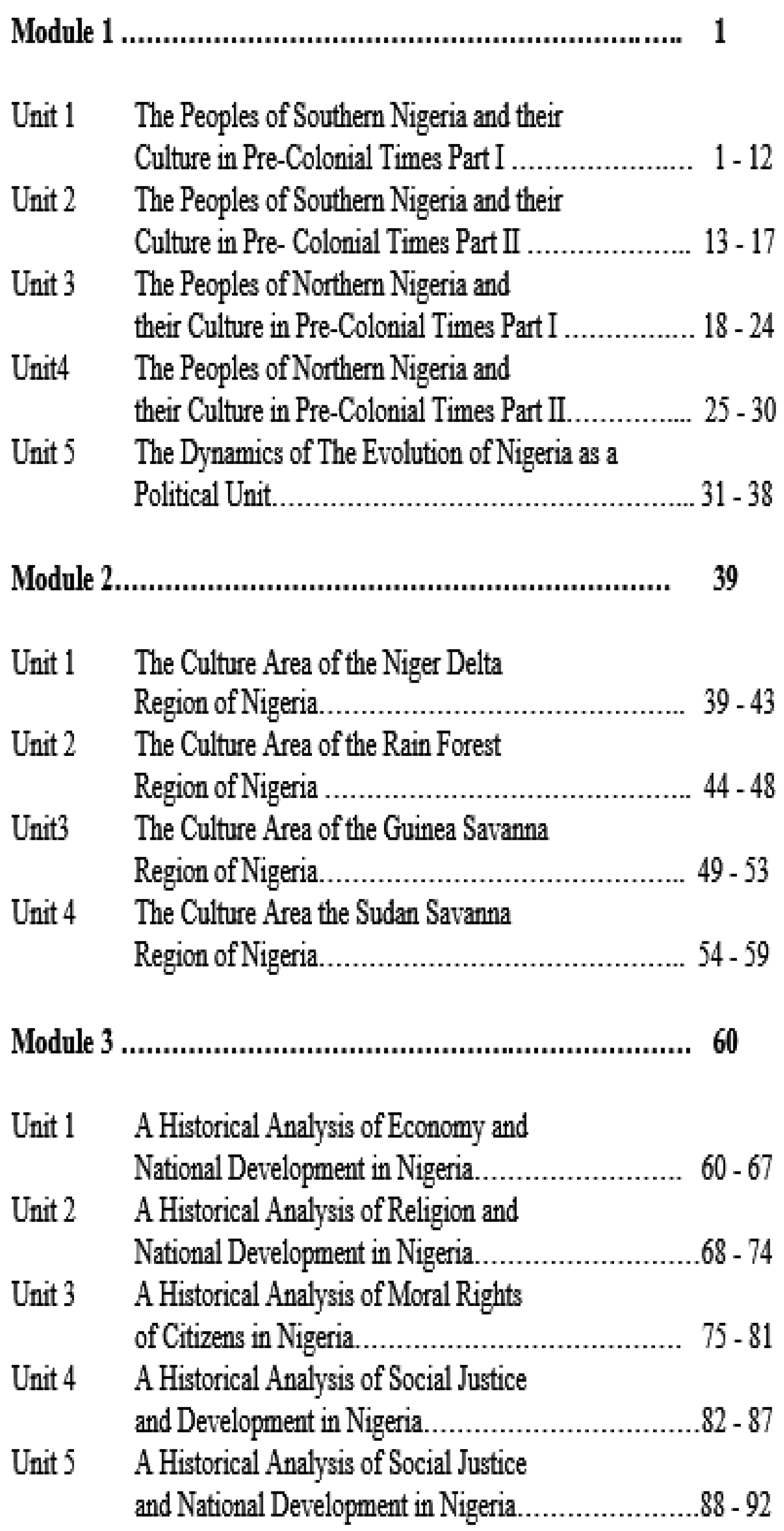

Nigerian Peoples and Culture: Course Modules

4. Afro-Hispanic Peoples and Culture: Proposed Course Topics

- The Americas before the Arrival of the Spanish;

- Afro-Hispanics in Colonial Spanish America;

- Afro-Hispanics in Post-colonial Spanish America;

- Afro-Hispanic Peoples in North America;

- Afro-Hispanic Peoples in Central America;

- Afro-Hispanic Peoples in the Caribbean;

- Afro-Hispanic Peoples in the Andean regions;

- Afro-Hispanic Peoples in the Southern Cone;

- Afro-Hispanic Contributions in Spanish America.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguirre Beltrán, Gonzalo. 1972. La población negra en México. México: Tierra Firme. [Google Scholar]

- Alley, David C. 1994. Integrating Afro-Hispanic Studies into the Spanish Curriculum: A Rationale and a Model. Afro-Hispanic Review 13: 3–8. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23053982 (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Andrews, George Reid. 1989. Los Afroargentinos de Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Flor. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, George Reid. 2004. Afro-Latin America, 1800–2000. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aretz, Isabel. 1977. Música y Danza (América Latina continental, excepto Brasil). In África en América Latina. Edited by Manuel Moreno Fraginals. México: Siglo Veintiuno Editors, sa, pp. 238–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ayorinde, Christine. 2004. Afro-Cuban Religiosity, Revolution, and National Identity. Gainsville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky, Sibylla. 2013. African Heritage in Latin America. Christian Science Monitor. February 12. Available online: https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Americas/2013/.../African-heritage-in-Latin-America (accessed on 19 November 2018).

- Busey, Christopher L., and Bárbara C. Cruz. 2015. A Shared Heritage: Afro-Latin@s and Black History. The Social Studies 106: 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, Lydia. 1996. El monte. La Habana: Editorial SI-MAR. [Google Scholar]

- Candelario, Ginetta E. 2007. Black Behind the Ears: Dominican Racial Identity from Museums to Beauty Shops. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Beatrice S. 1982. The Infusion of African Cultural Elements in Language Learning: A Modular Approach. Foreign Language Annals 15: 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, Nicole-Marie, and Anthony R. Jerry. 2013. Drawing the Lines: Racial/Ethnic Landscapes and Sustainable Development in the Costa Chica. The Journal of Pan African Studies 6: 210–27. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. 1987. La otra ciencia: El vodudominicano como religión y medicina populares. Santo Domingo. New York: Anson P. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, Juan E. 2002. Mestizo Nations: Culture, Race and Conformity in Latin American Literature. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Granda, Germán. 1988. Lingüística e Historia. Temas Afro hispánicos. Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid. [Google Scholar]

- De La Torre, Domitila. 2008. The Immense Legacy of Africa in the Latin American Literature and Music. Available online: http://www.uh.edu/honors/Programs-Minors/honors-and-the-schools/houston-teachers-institute/curriculum-units/pdfs/2008/african-history/de-la-torre-08-africa (accessed on 22 July 2018).

- DeCosta, Miriam S. 1973. Africanizing the Spanish Curriculum for the Undergraduate. Edited by Herman F. Bostick. New York: The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. [Google Scholar]

- Deive, Carlos Esteban. 1992. Vodu y magia en Santo Domingo, 3rd ed. Santo Domingo: Fundación cultural dominicana. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Kwame. 2006. Beyond Race and Gender. Recent Works on Afro-Latin America. Latin American Research Review. Austin: University of Texas Press, vol. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, Jorge. 2006. Racializing Ethnicity in the Spanish-Speaking Caribbean: A Comparison of Haitians in the Dominican Republic and Dominicans in Puerto Rico. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies 1: 231–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulitzky, Ariel. 2001. A Region in Denial: Racial discrimination and racism in Latin America. Beyond Law 8: 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Edewor, Patrick, Yetunde A. Aluko, and Sheriff F. Folarin. 2014. Managing Ethnic and Cultural Diversity for National Integration in Nigeria. Developing Country Studies 4: 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- England, Sarah, and Mark Anderson. 1999. Authentic African Culture in Honduras? Afro-Central Americans Challenge Honduran Indo-Hispanic Mestizaje. Paper Presented at the XXI Latin American Studies Association International Congress, Chicago 24–27 September Chicago. Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/ar/libros/lasa98/England-Anderson.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2016).

- Fernández, Sujatha, and Jason Stanyek. 2007. Hip-Hop and Black Spheres in Cuba, Venezuela, and Brazil. In Beyond Slavery: The Multilayered Legacy of Africans in Latin America and the Caribbean. Edited by Darién J. Davis. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Sánchez, Paloma. 2015. Racial Ideology of Mestizaje and its Whitening Discourse in Memín Pinguín. Revista de Lenguas Modernas 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, Alejandro. 2008. De la “desaparición” de los negros a la “reaparición” de los Afrodescendientes: comprendiendo la política de las identidades negras, las clasificaciones raciales y de su estudio en La Argentina. In Blackness in the Andes. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales Centro de Estudios Avanzados, Programa de Estudios Africanos. Available online: http://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/clacso/coediciones/20100823031819/08frig.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2018).

- Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. 2011. Black in America. Available online: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/black-in-latin-america/ (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- Gradín, Carlos. 2011. Occupational Segregation of Afro-Latinos. Working Paper: 11/05. JEL Classification: D63, J15, J16, J71, J82. Grant ECO2010-21668-C03-03/ECON) and Xunta de Galicia (grant 10SEC300023PR). Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/vig/wpaper/1105.html (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- GST 201-Nigerian Peoples and Culture. 2008. Lagos: National Open University of Nigeria. ISBN 978-058-425-0. Available online: nouedu.net/sites/default/files/2017-03/gst%20201.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2016).

- Hensel, Silke. 2007. Africans in Spanish-America: Slavery, Freedom and Identities in the Colonial Era. INDIANA 24: 15–37. Available online: https://journals.iai.spk berlin.de/index.php/indiana/article/view/1943/1581 (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Hooker, Juliet. 2005. Indigenous Inclusion/Black Exclusion: Race, Ethnicity and Multicultural Citizenship in Latin America. Journal of Latin American Studies 37: 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Richard L. 1975. Black Phobia and the White Aesthetic in Spanish American Literature. Hispania 58: 467–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Shirley M. 1978. Afro-Hispanic Literature: A Valuable Cultural Resource. Foreign Language Annals 11: 421–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, James H. 1987. Strategies for Including Afro-Latin American Culture in the Intermediate Spanish Class. Hispania 70: 679–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzua, Jose L. 1967. Morenada: Una Historia de la Raza Africana en el Rıo de la Plata. ed. Buenos Aires: Editorial Schapire. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, Sobeira. 2012. Afro-Latino/a Identities: Challenges, History, and Perspectives. Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal 9: 5. Available online: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium/vol9/iss1/5 (accessed on 22 July 2018).

- Lewis, Marvin A. 1996. Afro-Argentine Discourse: Another Dimension of the Black Diaspora. Colombia: University of Missouri Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liboreiro, Cristina M. 1999. ¿No Hay Negros Argentinos? Buenos Aires: Editorial Dunken. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John. 1989. The Speech of the Negro Congos of Panama: A Vestigial Afro-Hispanic Creole. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John. 1994. El lenguaje afroperuano: eslabón entre África y América. Anuario de Lingüística Hispánica 10: 179–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John. 1999. Creole-to-creole contacts in the Spanish Caribbean: the genesis of Afro-Hispanic language. Publications of the Afro-Latin American Research Association (PALARA) 3: 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John. 2004. Nuevas perspectivas sobre el español afrodominicano. Available online: http://www.personal.psu.edu/jml34/afrohait.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2016).

- Lipski, John. 2005. A History of Afro-Hispanic Language: Five Centuries, Five Continents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John. 2007. A blast from the past: ritualized Afro-Hispanic linguistic memories (Panama and Cuba). Journal of Caribbean Studies 21: 163–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John. 2008. Afro-Bolivian Spanish. Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert/Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John. 2008. Afro-Paraguayan Spanish: The Negation of Nonexistence. The Journal of Pan African Studies 2: 2–38. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Echazábal, Lourdes. 1998. Mestizaje and the discourse of national/cultural identity in Latin America, 1845–1959. Latin American Perspectives 25: 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massone, Marisa, and Manuel M. Muñiz. 2017. Slavery and Afro-descendants: A proposal for teacher training. Educação & Realidade 42: 121–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megenney, William W. 1999. Aspectos del lenguaje afronegroide en Venezuela. Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Megenney, William. 2000. The Fate of Some Sub-Saharan Deities in AfroLatin American Cult. Available online: groups.lasa.international.pitt.edu/Lasa2000/Megenney.PDF (accessed on 11 October 2016).

- Miller, Marilyn Grace. 2004. Rise and Fall of the Cosmic Race: The Cult of Mestizaje in Latin America. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morel, Cynthia. 2006. Invisibility in the Americas: Minorities, peoples and the Inter-American Convention against All Forms of Discrimination and Intolerance. Revista Cejil. AÑO I Número 2. Debates sobre Derechos Humanos y el Sistema Interamericano. Available online: www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/r24799.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2018).

- O’Toole, Rachel Sarah. 2013. As Historical Subjects: The African Diaspora in Colonial Latin American History. History Compass 11: 1094–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, Fernando. 1990. Glosario de Afronegrismos. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Paschel, Tianna S. 2010. The Right to Difference: Explaining Colombia’s Shift from Color Blindness to the Law of Black Communities. American Journal of Sociology 116: 729–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paullier, J. 2011. Venezuela, espiritismo y santería. BBC News Mundo. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2011/10/111017_venezuela_religion_santeria_espiritismo_jp (accessed on 18 October 2016).

- Peréz, Elvia. 2004. From the Winds of Manguito: Cuban Folktales in English and Spanish. Westport: Libraries Unlimited. [Google Scholar]

- Restall, Matthew. 2000. The African Experience in Early Spanish America. The Americas 57: 171–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochin, Refugio I. 2016. Latinos and Afro-Latino Legacy in the United States: History, Culture, and Issues of Identity. Professional Agricultural Workers Journal 3: 2. Available online: http://tuspubs.tuskegee.edu/pawj/vol3/iss2/2 (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Rodríguez-Mangual, Edna M. 2004. Lydia Cabrera and the Construction of an Afro-Cuban Cultural Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salawu, Bashiru, and A. O. Hassan. 2010. Ethnic politics and its implications for the survival of democracy in Nigeria. Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research 3: 28–33. Available online: http://www.academicjournals.org/jpapr (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Schavelzon, Daniel. 2003. Buenos Aires Negra. Arqueología histórica de una ciudad silenciada. Buenos Aires: Emecé. [Google Scholar]

- Smeralda, Juliette. 2011. Entrevue/Interview. Available online: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kP6ZJX-HMXM&list=UUtn9IX7pVL6MZUwnd90n8g&index=2&feature=plcp (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Solomianski, Alejandro. 2003. Identidades Secretas: La Negritud Argentina. Rosario: Beatriz Viterbo. [Google Scholar]

- Stepan, Nancy Leys. 1991. The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Telles, Edward E. 2004. Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Telles, Edward E., and René Flores. 2013. Not Just Color: Whiteness, Nation, and Status in Latin America. Hispanic American Historical Review 93: 411–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, Edward E., and Denia García. 2013. Mestizaje aand Public Opinion in Latin America. Latin American Research Review 48: 130–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thésée, Gina, and Paul R. Carr. 2012. The 2011 International Year for People of African Descent (IYPAD): The paradox of colonized invisibility within the promise of mainstream visibility. Decolonization: Indigeneity. Education & Society 1: 158–80. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Saillant, Silvio. 1998. The tribulations of blackness: stages in Dominican racial identity. Callaloo 23: 1086–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, Harry G., Jorge Guitart, and Anthony Papalia. 1979. Effects of Cultural Presentations on Attitudes of Foreign Language Students. Modern Language Journal 63: 177–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchechukwu, Purity A. 2016. Afro-Hispanics and Self-Identity: The Gods to the Rescue? OGIRISI: a new Journal of African Studies 12: 319–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN International Decade for People of African Descent. 2015–2024. Available online: https://www.questia.com/read/1P3-3711604141/uninternational-decade-for-people-of-african-descent (accessed on 15 October 2016).

- Villegas Rogers, Carmen. 2006. Improving the Visibility of Afro-Latin Culture in the Spanish Classroom. Hispania 89: 562–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, Peter. 1997. Gente negra, Nación Mestiza: las Dinámicas de Identidades Raciales en Colombia, trans A.C. Mejía. Ediciones Uniandes. Ediciones de la Universidad Antioquia. Colombia: Siglo del Hombre Editores, Instituto Colombiano de Antropología. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, Peter. 2005. Rethinking Mestizaje: Ideology and Lived Experience. Journal of Latin American Studies 37: 239–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, Peter. 2008. Race in Latin America. In Blackwell Companion to Latin American Anthropology. Edited by Deborah Poole. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 177–92. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Sonja. 2013. Teaching Afro-Latin Culture through Film: Raices de Mi Corazón y Cubas Guerritas de los Negros. Hispania 96: 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Olly. 1985. The Association of Movement and Music as a Manifestation of a Black Conceptual Approach to Music-Making. More than Drumming: Essays on African and Afro-Latin American Music and Musicians. Edited by Irene V. Jackson. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

| YouTube Videos | Websites |

|---|---|

| Afro-Argentino | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6536IZD1f90 |

| Afro-Colombiano | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XaPjcjrxWE |

| Afro-Mexicano | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5pjISf0M9XU |

| Afro-Boliviano | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ANReMTWjRVU |

| Afro-Peruano | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gi6dsB3T1kk |

| Afro-Ecuatoriano | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgesTzMCwnw |

| Afro-Chileno | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=02oZwkjkYEo |

| Afro-Paraguayo | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=teQ31xrINPk |

| Afro-Costarricense | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6NHWMNmjJk |

| Afro-Guatemalteco | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OZvohb31P_Q |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uchechukwu, P.A. A Proposal for Afro-Hispanic Peoples and Culture as General Studies Course in African Universities. Humanities 2019, 8, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010034

Uchechukwu PA. A Proposal for Afro-Hispanic Peoples and Culture as General Studies Course in African Universities. Humanities. 2019; 8(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleUchechukwu, Purity Ada. 2019. "A Proposal for Afro-Hispanic Peoples and Culture as General Studies Course in African Universities" Humanities 8, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010034

APA StyleUchechukwu, P. A. (2019). A Proposal for Afro-Hispanic Peoples and Culture as General Studies Course in African Universities. Humanities, 8(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010034