Abstract

Images of atrocity are deeply problematic, in that they potentially create a tension between form and content and are often accused of re-victimization, aesthetization of suffering, compassion fatigue and exploitation. As an alternative, therefore, there is considerable potential in examining images associated with atrocity that do not depict the actual act of violence or the victim itself, but rather depict the material presence of the spaces and objects involved in such acts. The temporality of the photograph is also fluid in this type of approach. This paper considers the work of four photographers (Edmund Clark, Ashley Gilbertson, Shannon Jensen, and Fred Ramos) who have used a “forensic aesthetic” in their practice.

Keywords:

photography; documentary; photojournalism; forensics; material turn; forensic turn; time; temporality; ethics; witnessing; things; counter-forensics; chronotype 1. Contact Relics

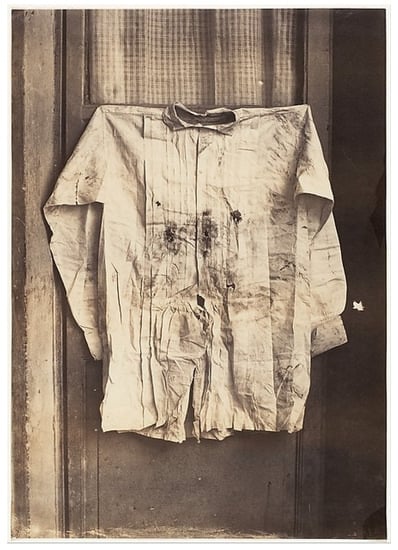

Its shoulders pinned to the door behind, squared off in an exaggerated expression of the form of the human body it is designed to cover, the stained and crumpled shirt hangs as if laid out by a servant for its owner to wear to a formal event (Figure 1). It appears as if a visage of its wearer, a stand-in for the actual presence of the human that it encased. The marks inscribed into its center coalesce into the schematic outline of eyes, a nose, and a mouth, taking on the form of the person who wore it, a symbolic representation of the shape of their body. However, this shirt is also a shroud; the marks in the center are inscribed by bullets, and the dark traces flowing from them are the stains of dried blood. The image has the passage of time imprinted into its surface and into its tonal values, with the white of sacrifice tainted by the dark streaks of blood. The history of the shirt can be imagined; how it was put on underneath a formal three-piece suit, how the bullets rented the fabric of the waistcoat and then the shirt, and how the life essence seeped out through them. Then, after this violent act, how the photographer pinned it carefully to the door to create a stage set upon which to document the artifact, creating a relic, with the marks of violence contact printed onto the material by the destruction of the life force of its owner.

Figure 1.

The Shirt of the Emperor, Worn during His Execution, François Aubert, 1867.

The forensic nature of this unsettling image gives it a haunting power over the imagination.1 It shows the bloody shirt worn by the ill-fated Austrian Archduke Maximilian I, appointed Emperor of Mexico by Napoleon III in 1864, and then overthrown and executed in the Cerro de las Campanas in Mexico on 19 June 1867 by the nationalist followers of Benito Juarez after the French withdrew their support.2 Taken by François Aubert,3 who had been the court photographer to the Emperor, this haunting image, along with another that depicted the waistcoat worn by Maximillian, also riddled with bullet holes, was widely distributed after the event as a carte de visite.4 The shirt thus took on a form analogous to a religious contact relic,5 with the dual materiality of the object and of the photograph printed on paper combining to create a tangible secular memento of the victim, shared by both supporters and detractors of the Emperor alike. The photograph itself became a material object, able to survive into the present, and able to tell its own story, often in conflict with official narratives. As Andrea Noble observes,

Aubert also photographed the corpse of the Emperor in its coffin, but his apparently deliberate staging of the shirt seemingly demonstrates an awareness of how the material trace of a life can arguably generate a more powerful visual connection with the imagination than the actual body itself. This trace of a trace of the traumatic event provides perhaps a more contemplative space in which the viewer can engage in a dialog with the image without the fear that the representation of explicit violence might force them to look away. How contemporary photographers have used this potential of images of traces, of things and spaces as an alternative to more graphic representations of trauma is therefore the theme of this paper.Understood as material artefacts that are bound up with questions of temporality—where time is fractured, splintered—photographs have the power to tell another kind of history that is at odds with the commemorative practices of the state and its linear, forward march.(Noble 2010, p. 95)

2. Traumatic Representation

Photographers who concern themselves with depicting suffering, whether as a result of open conflict, social exclusion, poverty or political violence, are faced with a set of deeply problematic and troubling ethical dilemmas that create a tension between form and content, and open them up to accusations of re-victimization, compassion fatigue, exploitation, and the aesthetization of suffering.6 Photographers are themselves frequently deeply aware of the paradox of the representation of trauma. The more intense and violent the trauma, the more the subject is liable to be re-victimized by the act of representation, and often the less able they are to give active consent to their participation in the exchange.7 However, the more violent that trauma becomes, the more valuable and important it becomes that the trauma is witnessed and introduced into social dialog. This is the central dilemma of the witness to atrocity, the more desperate and severe the situation, the more necessary it is to be reported. This problematic dichotomy about whether the event should be photographically documented or not troubles Andrea Liss, who argues that the “gap in the difference between the reality of the photographed and the photographer creates an obscenity of representation” and that the distribution of such images in the “commercial vehicles of publication and the political passivity in much documentary photography create a doubled situation of martyrology in which the viewing of the image “re-victimizes the victim’” (Liss 1998, p. 15).

Certain images, particularly those of “limit events”8 such as atrocities, thus fracture the framing norms of acceptable social behavior, creating moments where the ethics of representation are so challenged as to make the images almost unviewable. The limit event is typically treated as something so far from everyday experience that it becomes so detached that the linkage between it and the flow of life is obscured, and the viewer is unable to encompass that it happened as part of a continuity of events rather than a disjunction. To circumvent this possibility, photographers have explored the potential of not depicting the subject of the suffering themselves, but rather the traces left behind by that person. The everyday, often-banal ephemera of life, when set in the context of an act of violence, can create a slippage, generating a traumatic rupture between the innocuous nature of the space or thing photographed, and the context in which knowledge about the fate of its owner creates a different reading of the photograph. In exploring this possibility, the traumatic rupture needs to be related back to its context, the limit event needs to be reconnected to the continuity of experience that extreme representation often severs it. In this, Michael Rothberg’s concept of “traumatic realism” can serve to reconnect the representation of atrocity to the often-banal context in which it occurs. Traumatic realism is defined as a point where

The concept of traumatic realism thus has a powerful role in its potential to mobilize the viewer to action against the wrongdoing or abuse, as by returning the traumatic tear to the context of the social fabric, it can make the audience aware of the interconnections of the ordinary and the extreme. Images that combine the traumatic event or evidence of it with another quality such as aesthetics or everydayness often lead to what can be viewed as a genre slippage, in which the expected tropes of meaning of the image are disturbed. Rothberg notes how traumatic realism is “marked by the survival of extremity into the everyday world and is dedicated to mapping the complex temporal and spatial patterns by which the absence of the real, a real absence, makes itself felt in the familiar plenitude of reality” (Rothberg 2000, p. 67). The viewer is therefore forced to confront a misalignment between elements of the operation of the image, perhaps between form and content, or form and caption. These unexpected slippages subvert the viewer’s expectations of how to interpret a photograph and provide potential points from which the audience must actively make sense of what is in front of them. They can thus provide a powerful mechanism for engagement, and potentially greater understanding, as the viewer must do significant interpretative work to understand the image, work that can lead to a greater feeling of involvement. I argue that such slippages generate disturbances in the reading of the image that can potentially enhance the engagement of the viewer by inviting them to think more deeply about the meaning of the image, going beyond its immediate, surface interpretation. This disjunction is potentially one of the most powerful processes to facilitate audience engagement with images that goes beyond passive reception. This creates a contradiction between form and content that potentially forces the viewer to think more deeply about the meaning of the image by creating a disturbance in the reading of the photograph. The dichotomy between what is seen on the surface of the image and what is known about the image’s context creates a space where the viewer must do more work to make sense of what the photograph is or does. This shifting from a passive viewing of the image where every element in the construction of its meaning is in harmony and agreement, to the dissonance of the genre slippage makes the image more complex, and therefore potentially demands more engagement from the audience in actively constructing the meaning in the photograph rather than passively receiving it. In the case of images of atrocity, perhaps those that do not show the act of violence itself but rather allude to it by depicting the perpetrator or the aftermath might engage the imagination more successfully than those whose more graphic content might prove repulsive. Such images of the absence of visible violence can lead the viewer into an imaginative engagement with the nature of atrocity and abuse, and the nature of those who perpetrate it.The extreme and the everyday are neither opposed, collapsed, nor transcended through a dialectical synthesis-instead, they are at once held together and kept forever apart in a mode of representation and historical cognition.(Rothberg 2002, p. 55)

3. The Durable Materiality of the Image

Photographs are, in a fundamental sense, carriers of traces;9 they are always of the past yet are seen in the present. They are tangible, material objects: things in themselves (whether physically as a print or virtually on a computer screen), and thus have both a physical material duration as objects as well as an embedded temporality within the image itself, preserving within the frame the ghostly shreds of the past as well as the understanding that that that past is no longer there. Although technologically determined, they are highly mediated by human agency. In their inherent materiality, they become durable vestiges of memory, yet open to interpretation and imagination. As Eyal Weizman argues, “material forms … can only reflect truth in fragments and ruins, and suggest uncertain, discontinuous, and lacunar interpretations” (Weizman 2014, p. 11). When the subject of the photograph is itself a trace it becomes a fragmentary trace of trace, generating a dual materiality, a thing (the photograph) that records another thing (the object depicted). As Kitty Hauser notes, a trace “marks a point at which a narrative coagulates and calls its own witness” (Hauser 2007, p. 62), becoming a form of embodied material witnessing to past events. When the image makes a trace its central focus, the viewer is encouraged to “re-enact in imagination that which might have caused the depicted marks to be made” (Hauser 2007, p. 79)

The frozen, suspended time in photographs oscillates between past and present, connecting moments in time, making connections fluidly like a river with its tributaries and forks rather than linearly like a road.10 It is important to note that this is not a “stilling” of time but rather a concentration of experience into an image that suggests time interrupted, retaining the sense of a time before the image and a time after it. The past thus endures into the present, and this interweaving of temporalities is essential to understanding the present, and the future, as well as the past, creating a “great patchwork of coexisting temporal horizons that create networks and connections between different times, different pasts” (Olsen 2010, p. 108). Photographs therefore, in a sense, “carry” time, moving between past, present, and future, a sense of occurrences before the photograph and possibilities afterwards, generating the “residue of continuous experience” (Moeller 1999, p. 44). Photographs of traces also rely for their hold on what anthropologist Deborah Poole has characterized as an “excess of description” (Poole 2005, p. 159), recording every detail in front of the lens. As the archeologist Laurent Olivier observes, “like archeology, photography inscribes events in matter” (Olivier 2011, p. 63), and like artifacts in a historical collection, they can be considered as museal objects. As such, the past is “not left behind but gathers and folds into the becoming present, enabling different forms of material memory” (Olsen 2010, p. 126). Photographs thus encapsulate a sense of “durable matter”, making the past tangible to the present, embodying time, making it tangible, apparent. As Hauser notes, “halting time, the photograph converts history and the passage of time into graphic signs which may or may not be legible to the viewer, depending upon their expertise and knowledge” (Hauser 2007, p. 101). However, time in photographs is not fixed, different temporalities can exist in different images. Some photographs speak of the past, some the present and some the future, some refer to varying combinations of them. The photograph can thus be characterized as a chronotype, where time and space are melded together such that the meaning of the image is determined by where it was taken as well as when. Bakhtin identifies the chronotype as when

The concentrated energy of the photograph, what the visual anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards has called the “intensity of presentational form—the fragment of experience, reality, happening … contained through framing” (Edwards 2001, p. 17) can create what Marianne Hirsch has characterized as a “heteropathic” effect, that of feeling and suffering with the other, leading the viewer to the identification that “‘It could have been me: it was me also’, and, at the same time ‘but it was not me’” (Hirsch 1998, p. 9). They invite the audience to enter the emotional space of the subject, to attempt to relate their experiences, their life, to that of the lives depicted in the image. This links the private with the public. When the photograph is of an object belonging to a person, or of a space occupied by a person, this heteropathic connection is amplified in the space generated by the lacuna between the presence and the absence of the owner.spatial and temporal indicators are fused into one carefully thought-out, concrete whole. Time, as it were, thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history.(Bakhtin 1981, p. 84)

4. The Forensic Turn

The genre of aftermath photography exploring the topography of sites of conflicts is well established,11 with its emphasis on the landscapes of violence and trauma and the hidden memories they can trigger. This approach often relies on a strategy using a large format camera. This creates an aesthetic of distancing and observation, combined with stillness and lack of obvious visual movement and energy, and high levels of detail. This combination elicits a different mode of viewing from the audience, who are encouraged to contemplate and explore the image in a slower and more considered manner than they might perhaps engage with a more photojournalistic one. As such, they can allow tiny elements of the image to become the most salient features, inviting the viewer to pore over the images in a detailed manner. They thus invite an almost forensic approach, or one similar to that of a military interpreter viewing aerial reconnaissance images. This detail invites the viewer into an active process of scanning the photograph, positioning them in a dialog with the image, and necessitating an investigative mode of engagement. The focus is often on the viewer deciphering the meaning of the image through a detailed exploration of the surface of the photograph, and a simultaneous imaginative reading of its topography. The viewer is thus presented with the visual evidence of the image, and then invited to enter into a discussion with it, interrogating the image as if a witness to the event itself. As such, the viewer is placed into the position of a secondary witness, bearing witness to the events that took place on that spot in the past, and is made aware of the trauma hidden beneath the apparently quiet surface of the photograph. However, some photographers as will be considered in this paper have also deployed a closer, more micro focus on objects and interior spaces, emphasizing the “thingness of the photograph”, again often informed by a forensic aesthetic. This “forensic turn” has some of its roots in the experiences of photojournalists in the wars that devastated the former Yugoslavia, in particular the negative experiences of witnessing atrocity in Bosnia and the subsequent attempt to respond to the challenges by more explicitly aligning themselves with human rights organizations in the Kosovo emergency as exemplified in the work of Giles Peress and Gary Knight.12 More broadly, this forensic turn has developed along with the “material turn”,13 placing increased emphasis in the role of the physical world that surrounds human activity, and attempting to challenge the state monopoly on the apparatus of investigation and evidence gathering, and the description of violence, in particular when carried out by state or quasi state agencies themselves. One of the key themes of the material turn in the discourse of memory is the way that the focus has shifted from extraordinary artifacts to the ordinary and every day. This echoes the turn in historical studies away from the grand narratives of rulers to the everyday lives of their subjects. Writing of the nature of our relationship to objects the archeologist Bjornar Olsen observes that the “thingness of the thing is probably easier to grasp in the less conspicuous, ordinary, and thus far more common objects” (Olsen 2010, p. 19). He notes that “our everyday dealings with things mostly take place in a mode of inconspicuous familiarity: unless broken, interrupted, or missing, things often pertain to a kind of shyness” (Olsen 2010b, p. 23). Such moments are often generated by a disturbance or interruption, causing them to “light up” and become noticeable in ways that they were not before. Because of this process, the viewer becomes aware of how the thing relates to its context and the world around it, often illuminating relations that were not seen or made apparent before. This highlighting of the thing in relation to its wider context establishes it as a part of a relational web of connections to its social uses.

An aesthetic of forensics, with close ups of details or a frontal depiction of a scene, is frequently deployed to give an evidentiary weight to the images. These “crime scene” photographs; however, only have the surface appearance of forensic images, although they often have the same frontal, simple aesthetic. For evidential purposes, they lack scales and measurements, the detailed locational captions, and the proof of a chain of custody of evidence that such judicial purposes demand. However, the aesthetic does expand the image beyond simple witnessing to generate a sense of the metaphoric and imaginative readings of the meaning of the photograph in their juxtapositions of objects within the frame and between frames. The temporality of a space or an object is in a sense continuous, it would have looked essentially the same moments before or after the image was taken, and in some cases days, weeks, or years before or after as well. This sense of a more continuous temporality in the depiction of spaces and objects extends the life of the image beyond the moment the shutter was released. These images form a kind of secondary witnessing, unlike eyewitness accounts of specific events, they operate with a different temporality, and thus a different act of witnessing, a secondary witnessing that aligns itself more with bearing witness and the giving of testimony rather than the immediacy of an eyewitness account. These multiple readings of the images suggest a genre slippage where the evidential force of crime scene photographs engages with the emotional response to more classic photojournalistic tropes.

5. A Conversation with the Subject

The photographers examined as case studies in this section have all responded to the challenges of the ethical problems of representing violence against the body, but also the challenges of representation of events that are un-photographable, either because they have already taken place, or because they are occluded from view by state censorship. As Eyal Weizman has argued, the forensic turn can become some counter-forensics, “a counter-hegemonic practice able to invert the relation between individuals and states, to challenge and resist state and corporate violence and the tyranny of their truth” (Weizman 2014, p. 11). They represent a small survey of photographers who have deployed this more “forensic” approach because of a sense of the failure of more conventional photojournalistic modes of representation.14 While they all come to the situations they encounter with a knowledge of the context gained through experience, research and existing knowledge, they also have all responded to the particularities and specifics of the scene they find themselves in front of. They attempt to find in the moment of encounter with the subject a visual form of representation that can aesthetically frame the situation in a way that allows the context to be coherently expressed, without the dangers of exploitation of the subject noted earlier that a more direct form of address could entail. This dialog with the subject lies at the heart of documentary and photojournalistic practice. Photographers frequently respond to the situation they encounter in a self-reflective conversation with the subject, through which they seek to they discover a form of representation that can deal with their experience of the situation in the moment of encounter with it, rather than a necessarily preordained concept that they bring to the scene, articulated in advance. They respond to the emotional and physical charge of the space or of the object, and in doing so discover a valid response to the encounter that can translate their experience of the moment into a tangible image.

They do share some common methodologies, however, including the concentration on spaces or objects to carry the message of their work, and on a typology15 that arranges similar items together to convey the sense of a pattern, of constituent elements of a larger scale issue. Mapping and collating multiple repetitions of the same occurrence is a fundamental part of human rights investigation work, to establish command responsibility of an act of atrocity or war crime, and these photographers borrow from that approach to create a visual argument that the scale of the problem they are addressing is not that of an individual isolated incident but rather a sustained, larger enterprise. They make sense of fragmentary evidence building it into a coherent presentation that does not use the traditional visual grammar of the photo essay with its variation in shots and linear narrative, but instead using the comparative study of patterns of similarity to make sense of the story.

Edmund Clark has engaged with the global state War on Terror in a series of works including Guantanamo, When the lights go out (2010), Control Order House (2013), and Negative Publicity: Artifacts of Extraordinary Rendition (2016). In each of these projects he combines his photographs of the spaces inhabited by alleged suspects and of the objects associated with them with textual evidence including redacted government documents, personal letters, maps, and surveillance photographs taken from state archives. In none of them does he actually photograph the people themselves, instead relying on imaging their environments as a way of countering the stereotypical assumptions that come with the label “terrorist”. As he argues

By focusing on the banal, everyday interior of the spaces that they are forced to occupy, he defuses the negative connotations of state propaganda, instead positioning the viewer in front of scenes that are as familiar and ordinary as their own living room,I’m not sure what use the representation of their human form would have because in most cases, pictures of Arab or South Asian men with beards is so toxic. People look at them and see for them the representation of someone who either they think is a terrorist or is connected to terrorism. I think not using those forms of representation is a way of taking that barrier out of the way in which the work may communicate or engage people.(Stear 2016)

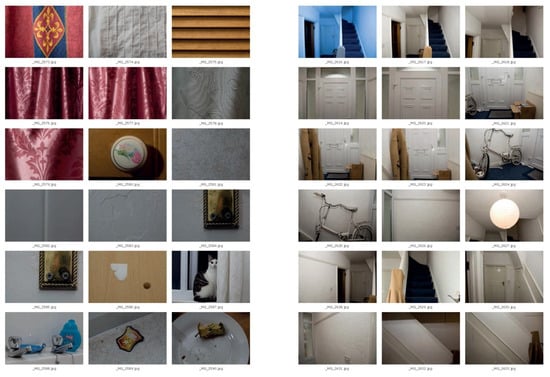

In Clark’s photographs, time is in the present continuous, the interior of the house is always present, a cage encasing the occupant in an environment that never changes, remains constant. In Control Order House,16 Clark methodically surveyed every surface of the interior of the dwelling, undertaking a forensic mapping of the space, creating page layouts in the book in which the suspect is socially entombed by the state (Figure 2). The images offer no hiding place in which the occupant could take refuge, and in doing so emphasis the control the state has over their entire existence, with Clark observing thatIt’s a way of taking the exotic out of the visual representation of this subject. It’s a way of bringing it closer to every possible viewer’s everyday experience of spaces, places that they inhabit, frequent, objects that they use. But it’s also showing that our spaces were used for this process. This happened in our cities, quiet suburbs, and quiet villages. It’s not an exotic thing; it’s happening in everyday spaces run by people who are just going about their business. And in a sense that also means that these kinds of spaces are to a certain extent contaminated by this.(Stear 2016)

The photographs evoke both surveillance and claustrophobia. It gives form to one of the locations where the control order experience took place. We are looking at the control imposed by the state on an individual and the implications this has for his personal and familial stability.(Brook 2013)

Figure 2.

_MG_2573.jpg–_MG_2633.jpg from Control Order House (Here Press, 2013, 2016), Edmund Clark.

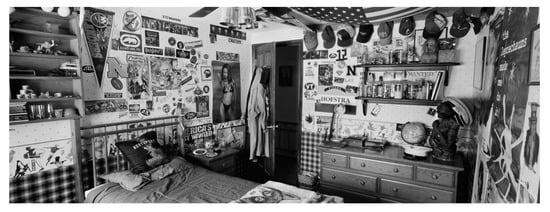

Ashley Gilbertson also sought to engage with a contemporary issue that was still ongoing in his Bedrooms of the Fallen (Gilbertson 2014) book (Figure 3). He created the project as a response to the issues he faced on covering the war in Iraq and its impact on the civilian population and on the American Military, and the ways in which the conflict was represented in the USA. The book is dedicated to Lance Corporal Billy Miller, who was killed in front of Gilbertson while he was embedded on a patrol with US forces in in Fallujah in 2004. They were climbing up the minaret of a mosque to photograph the body of a militant sniper who had been killed there, when as Gilbertson describes, “Moments before we reached the top, Miller was shot pointblank by an enemy fighter. I ran out as fast as I could, covered in Miller’s blood, forever changed. I came home … Billy Miller didn’t. I needed to photograph his absence.” (Chisholm 2014). Troubled by this experience, and by what he called the “failure of people to engage with the pictures I took while I was there and, I think, my failure as a photographer to present them freshly” (Chisholm 2014) he worked for seven years to research, locate and arrange access to the families of over 40 coalition force military who had been killed in action, and whose bedrooms had been preserved by their loved ones in exactly the way they had been left when the soldier left for their tour of duty. Writing the in introduction to the book, he explained that

When we lived with our parents, most of us had one room to ourselves. Our bedroom was the space we took ownership of, and in it we placed the things we loved most, reminders of what we longed for and aspired to. It was a place to which we could retreat from the world and feel protected. There we could express ourselves without judgment, and only our mothers could make us clean it.(Gilbertson 2014)

Figure 3.

Marine Cpl. Christopher G. Scherer, 21, was killed by a sniper on 21 July 2007, in Karmah, Iraq. He was from East Northport, New York. His bedroom was photographed in February 2009. Ashley Gilbertson, VII Agency.

Gilbertson saw the work as about how the families dealt with their loss, “The work is all about the living, about how they’re grieving. My work was missing the central point that they were grieving over the absence of somebody. How do you shoot that absence?” (Nolan 2011) He saw these as charged spaces as if in “some historic memorial. I would never touch anything. I would rarely even touch the light switch. I felt bad putting my tripod on the carpet because I felt I was disturbing something” (Nolan 2011), feeling that they were imbued with a tangible sense of the absence of their occupant: “I don’t believe in spirits or ghosts, or even god, but these rooms have so much power. I refuse to touch anything in the room. I feel like in some ways I’m on an archeological dig” (Nolan 2011). Shot in black and white on a panoramic camera, the images are respectful, framed as if the viewer has just entered the room, with the detail of every object and surface carefully rendered by soft even light. Gilbertson explained that he used this approach “so that the viewer had an even playing field to explore the objects in the room. I didn’t want colors to lead you away from things in their bedrooms that might connect with a viewer.” (Nee 2011). They are not dramatic, over lit images, instead they speak with a quiet reverence for the loss incurred by the families, and by extrapolation for all the families of coalition military (and by extension all those soldiers who never came home from war). While the work does only describe one particular set of circumstances and does not seek to engage with for example the homes of Iraqi or Afghan civilian casualties, it does question the role of the state in using the military as a political tool. As Phillip Gourevitch argues in the book’s introduction the state tried to minimize and erase the deaths from public consciousness

Gilbertson sought to use his calm, reflective approach to make an emphatic connection with the viewer that brought home the cost of the conflict by charting its cost in his survey of intimate spaces that could belong in any family home instead of photographs from a distant war. He acknowledged his sense of failure in the representation of the ongoing conflict, sensing that in the bedrooms there was a potentially more powerful and personal connection,This loss has received only faint and fleeting official recognition. Mourning is treated as a private matter, as if these dead belonged only to their comrades and kin, and not to us all. For many years, the government, fearful of a negative effect on fragile public opinion, forbade the publication not only of images of combat casualties, but even of flag-draped caskets coming home. But isn’t it a dishonor to the dead to try to hide them from the nation they served?(Gilbertson 2014)

Although both Control Order House and Bedrooms of the Fallen address the domestic space they produce very different responses. In Clark’s photographs, time is in the present continuous, the interior of the house is always present, remains constant. The formal strategy depicts detailed micro analysis in a comprehensive coverage of the entire space, with the color close-up images with their use of direct flash and framing seemingly generated by a machine set to systematically record every surface. This mosaic of images imparts the feeling of there being no hiding place in the space, with the flash exaggerating the sense that no detail of the space can be overlooked. The camera is intruding into the domestic space, violating it with its dehumanizing stare into every private nook and cranny. In Bedrooms of the Fallen, time is interrupted, stopped, and then frozen. These domestic interiors of what should be places of comfort, safety and refuge will never change again, as the life force that should disturb and rearrange them is no longer present. The bed will never again be rumpled, the books never read, the soft toys never held. The camera viewpoint surveys the whole scene in front as if from the perspective of someone standing at the door, at a reverential distance, as if standing before an altar. Gilbertson’s aesthetic creates a testimonial shrine to loss, while Clark’s generates a state controlled and surveyed cage encasing the occupant that never changes.The tragedy and the finality of this space was, to my heart, a more telling and honest explanation of what I had witnessed in Iraq than the countless photographs I had made there. The exploding bombs, morgues overflowing with corpses, and wounded soldiers being loaded onto helicopters were thousands of miles away. But in bedrooms like this, it felt like the conflicts were just outside, pressing against the walls.(Chisholm 2014)

The photographic temporality of Shannon Jensen’s typology of refugee’s shoes entitled A Long Walk, is also in the present continuous, but also in the past and the future. These shoes have a biography, they are worn, repaired, mismatched. They bear the imprint of the passage of both time and space, as they have been worn down by months and years of walking to escape persecution and fear. However, they are still worn today by their owners, who have no alternative to eking out the life of the shoe as long as possible, and they will continue to be worn into the future, as the safety of these refugees is still not secure. Jensen made the series as a result of the failure of her more conventional reportage coverage of the crisis in South Sudan in 2012 to gain any attention in mainstream media. She recounts how

She was told by one organization that they were “sort of refugeed out” (Estrin 2014), and asked herself “what, this isn’t serious enough for you? Aid workers described it as an emergency within an emergency within an emergency.” (Boyd 2014). However, she also felt that perhaps she was failing the situation in her own formal strategy, recounting how “I got all of the obvious pictures out of my system.” she said. “It’s only after I exhausted myself photographically, and was still unsatisfied, that I was forced to think differently.” (Estrin 2014) She was struck by the footwear of the refugees, noticing howI took the standard documentary-photojournalism pictures. The kind you see in magazines and newspapers, and I thought, it was a really big deal. These refugees had been walking for three to six weeks, carrying food, water, and what little possessions they had besides that. But news organizations weren’t interested in the standard documentary images. They said, if it gets more serious, let us know.(Boyd 2014)

Inspired in part by having seen Gilbertson’s Bedrooms, she began to ask the refugees if she could photograph their shoes and interview them about their experiences; the response was almost universally positive, to the extent that they sometimes even queued to have the photographs made. “People understood intuitively what I was doing…. They clearly understood, the shoes were a testament of their journey and what they’d been through.” (Boyd 2014). Shoes have a unique relationship to their owner, they literally bear the imprint of the form of their owner, unlike most other forms of clothing they shape themselves over time to become a negative of the physical body (Figure 4). As Jensen notes, they bear the traces of the precarious life of their owners,there was a huge diversity of shapes and colors, many of them showed a huge amount of wear, that paid testament to the arduousness of their journey, the trek they had made. Many of them had these small repairs, stitches, pieces of melted plastic, that paid testament to the determination, the persistence, necessary to get through, to get to safety.(Boyd 2014)

The incredible array of worn-down, ill-fitting, and jerry-rigged shoes formed a silent testimony to the arduous nature of the trek, the persistence and ingenuity of their owners, and the diversity of these individuals thrown together by tragic circumstance. Jensen felt that the shoes provided a different form of connection between the subject and the audience to that of a more conventional portrait or photojournalistic image.(Jensen 2014)

Figure 4.

The shoes of refugees who fled the Blue Nile State, reaching the border of South Sudan in May & June of 2012, Shannon Jensen.

She presented the set, presented as a grid of over 60 pairs of shoes, to her contacts in the press, and they were immediately taken up by a range of publications, and were published in Newsweek International, Stern, Geo, Vanity Fair (Italy) and GQ (Russia).17 Jensen felt that they asked more of the audience than more conventional representations,

As she honestly accepts, the aesthetic in the images is simple, direct, and straightforward, but this simplicity is in fact what gives the work its power and hold on the attention of the audience, although she notes that “These pictures are pictures that a 12-year-old could take. They are the most unskilled pictures I have ever taken in my professional career, but they’re clearly the most effective” (Estrin 2014). The work was exhibited as part of the Open Society Foundations’ “Moving Walls” exhibition at the society’s New York headquarters, and as the shows curator, Amy Yenkin recalls, had a profound effect on audiences, who “rather than dismiss the story as a crisis happening in a faraway place that has nothing to do with them, visitors are moved by the images. They want to go deeper…. A personal connection becomes the opening to the larger story” (Yenkin 2014).I hope the pictures ask more of the viewer than just the simple pity you feel when you look at images of terrible things that have happened to people. Because they don’t have a portrait attached to them, they don’t show the individual. Because I think it’s more effective to ask the viewer to look at the shoes, the name the age and where they’re from, and spend a little time with it. To imagine who this person is, and what they’ve been through. What if that was your pair of shoes and that represented a journey you had to make?”(Boyd 2014)

Fred Ramos, working in El Salvador, also felt that the more conventional approach he was taking to the gang violence that has plagued the county was also not telling the story effectively. He began to work on a project about the Desaparecidos (the disappeared), whose bodies are often found in anonymous shallow graves. Thousands of victims have been murdered and their remains hidden, and yet the state still has no effective way to investigate these crimes and identify the exhumed bodies that are recovered, with internal government conflicts meaning that no DNA database has been established. He explains how

As with Peress, Knight and Gafic in the former Yugoslavia, Ramos worked closely with the forensic investigators who were exhuming the remains. He took images of the clothes recovered from the victims’ bodies, laid out against a white background, with the fabric torn, rent, and decayed by the passage of time in the ground. (Figure 5) These fragile textiles, almost translucent, mark out the shape of the human form, appearing to grow to life size in the field of view of the viewer. Some are almost complete figures, others are missing limbs, and some are just a few scraps of bloodstained material. Each imager sis presented with data about the location the body was found, the gender, age, how long it had been missing, and the date of recovery. The work was originally published as “El Último Atuendo de los Desaparecidos” (The Last Outfit of the Missing) in the Salvadoran newspaper El Faro, and was subsequently published worldwide after it was awarded a prize in the 2014 World Press Photo Awards. Ramos and the newspaper published the work in the hope that the clothes could help families identify a missing person. He explains that “I thought the power that each one of these outfits had to tell the stories of the disappeared was great, and moreover, it gave a human element to a problem that had only been told through figures.” (Booker 2014) The photographic time in these images is also stopped dead at the point of the death of their wearer, but it also projects backward temporally to imagine the life that was cut short, the delicate details of the clothes telling stories about their wearer, the jeans, hoodies, and logos desperately familiar and mundane symbols of globalization.I was documenting the work of forensic anthropologists from the Institute of Legal Medicine, and I realized how important the clothes of the exhumed were to them. … They hope that through those clothes the families can recognize their missing relatives,(Booker 2014)

Figure 5.

1 February 2013. Time: 15:00 Location: outskirts of Apopa, San Salvador Gender: male Age: between 15 and 17 years old. Time of disappearance: approximately one year previously. Fred Ramos.

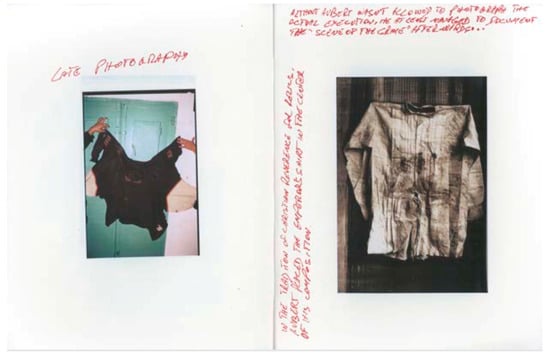

6. An Era of Traces

In his book, The Resolution of the Subject, (2016) Miki Kratsman paired the shirt of the Emperor with another torn and tattered one that had been taken from the corpse of a Palestinian killed by Israeli soldiers.18 (Figure 6) Making an explicit reference to the genre of aftermath and late photography, the pairing also draws allusions to the passage of time and to the continuity of photographic representation. It also, however, emphasizes the differing values placed both on the value of a life and on the value of a photograph. The image of the Emperor’s shirt was treasured and venerated as a carte de visite, and hi life recorded in the history books, but the life of the Palestinian protestor went unnoticed and unrecorded except for Kratsman’s depiction of the trace of their existence. However, the bloodied shirts both take on a more universal role as symbols of violence, as he observes in the book, the photograph oscillates between extreme specificity and a more general social value, especially when set into a more defined context as he does in The Resolution of the Suspect;

The specificity of a certain event became less relevant as such, and more relevant as a generic form of event. Not the specific road accident, a specific murder case or fire, but “an accident”, “a murder”, or “a fire”. This renewed definition included several things: taking a stand, refusing to try to illustrate the text, and relating to events as having a historical significance beyond their importance on the morrow when they appear in the press.(Kratsman and Azoulay 2016, p. 40)

Figure 6.

Diptych from the Resolution of the Suspect, Miki Kratsman (2016).

As Francesco Mazzucchelli has noted, “traces (whether spatial, architectonic, biological, or material remains) are thus used increasingly in the processes that construct collective memory landscapes” (Mazzucchelli 2017, p. 175), and they can be considered as “condensed narratives” (Mazzucchelli 2017, p. 178), that concentrate memory into material form. Through this process of material embodiment, the photograph can crystallize the essence of a scene, as “the vague and ambiguous become concrete and the raw and the physical are made meaningful” (Olsen 2010, p. 35). This transformation endows the thing photographed with the qualities of the person that possessed it, enhancing the connection between the viewer and the subject through the object rather than directly through an image of the person themselves. In this “era of traces” (Mazzucchelli 2017, p. 170), photographs can thus act as embodied sites that can transfer a sense of experience through space and time. Images of spaces and things have a different temporality to those of people in the sense that they are not images of events, but rather of states of presence—or absence. By paying attention to things, to details and to objects, the photograph can elevate them from the status of unnoticed elements into that of significant carriers of emotional and psychological depth and meaning.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Baer, Ulrich. 2002. Spectral Evidence. The Photography of Trauma. Cambridge: MIT. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1981. Form of Time and Chronotope in the Novel. In The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist. Austin: UTP, pp. 84–258. [Google Scholar]

- Booker, Maia. 2014. What They Wore to the Grave: The Last Outfits of El Salvador’s “Disappeared”. New Republic. September 16. Available online: https://newrepublic.com/article/119446/photos-fred-ramos-last-outfit-missing (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Boyd, Clark. 2014. How Shoes Can Tell the Plight of Refugees in South Sudan. PRI. February 3. Available online: https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-02-03/how-shoes-can-tell-plight-refugees-south-sudan (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Brook, Pete. 2013. This Incredibly Boring House Is a UK Terror Suspect’s Lockdown. Wired. April 15. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2013/04/edmund-clark-control-order-house/ (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Brown, Bill, ed. 2003. A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Bill, ed. 2004. Things. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buchli, Victor, ed. 2002. Material Culture Reader. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 2009. Frames of War: When Is life Grievable? London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Campany, David. 2003. Safety in Numbness: Some remarks on the problems of “Late Photography”. In Where Is the Photograph? Edited by David Green. Brighton: Photoworks/Photoforum. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, Christie. 2014. Bedrooms of the Fallen: Preserved by Their Families as Memorials to Loved Ones Lost. Available online: http://archives.cjr.org/on_the_job/bedrooms_of_the_fallen.php (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Danto, Arthur. 2003. The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art. Rockford: Open Court. [Google Scholar]

- Domanska, Ewa. 2006. History and Theory. Middletown: Wesleyan University, vol. 45, pp. 337–48. ISSN 0018-2656. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2001. Raw Histories. Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Estrin, James. 2014. A Sudanese Refugee Crisis, Photographed From the Ground Up. Lensblog NY Times. January 27. Available online: https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/01/27/a-sudanese-refugee-crisis-photographed-from-the-ground-up/?mcubz=0 (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Geismar, Haidy, and Heather A. Horst. 2004. Materializing ethnography. Journal of Material Culture 9: 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigliotti, Simone. 2003. Unspeakable Pasts as Limit Events: The Holocaust, Genocide, and the Stolen Generations. Australian Journal of Politics & History 49: 164–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson, Ashley. 2014. Bedrooms of the Fallen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano, Frank. 2015. Miraculous Images and Votive Offerings in Mexico. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 172–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Kitty. 2007. Shadow Sites Photography, Archaeology, and the British Landscape 1927–1955. Oxford: Oxford Historical Monographs. [Google Scholar]

- Herschdorfer, Nathalie. 2011. Afterwards: Contemporary Photography Confronting the Past. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Marianne. 1998. Projected memory: Holocaust photographs in Personal and Public Fantasy. In Acts of Memory. Lebanon: University Press of New England. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Shannon. 2014. A Long Walk. Inge Morath Award. September 15. Available online: http://ingemorath.org/shannon-jensen-a-long-walk/ (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Kratsman, Miki, and Ariella Azoulay. 2016. The Resolution of the Suspect. Santa Fe: Radius Books/Peabody Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin, Eleanor A. 2016. “Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg’s Shirt,” Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion. Available online: https://mavcor.yale.edu/conversations/object-narratives/carte-de-visite-photograph-maximilian-von-habsburg-s-execution-shirt (accessed on 14 July 2018). [CrossRef]

- Levitt, Laura S. 2018. “Miki Kratsman, Diptych from The Resolution of the Suspect.” Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 2. Available online: https://mavcor.yale.edu/mavcor-journal/miki-kratsman-diptych-from-the-resolution-of-the-suspect (accessed on 14 July 2018). [CrossRef]

- Liss, Andrea. 1998. Trespassing through Shadows, Memory, Photography and the Holocaust. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, Paul. 2014. The Forensic Turn: Bearing Witness and the ‘Thingness’ of the Photograph. In The Violence of the Image: Photography and International Conflict. Edited by Liam Kennedy. New York: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucchelli, Francesco. 2017. From the “Era of the Witness” to an Era of Traces. Memorialisation as a Process of Iconisation? In Mapping the ‘Forensic Turn’ Engagements with Materialities of Mass Death in Holocaust Studies and Beyond. Edited by Zuzanna Dziuban. Vienna: New Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, Susan. 1999. Compassion Fatigue. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nee, Shawn. 2011. Interview: Ashley Gilbertson’s “Bedrooms of the Fallen”. Available online: https://boywithgrenade.org/2011/05/18/interview-ashley-gilbertsons-bedrooms-of-the-fallen/ (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Noble, A. 2010. Photography and Memory in Mexico: Icons of Revolution. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, Rachel. 2011. A Conversation with Photographer Ashley Gilbertson. Available online: https://6thfloor.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/17/a-conversation-with-photographer-ashley-gilbertson/?mcubz=0 (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Olivier, Laurent. 2011. The Dark Abyss of Time. Lanham: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Bjornar. 2010. In Defense of Things: Archaeology and the Ontology of Objects. Lanham: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, Deborah. 2005. An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies. The Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 159–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, Mark, Holly Edwards, and Erina Duganne. 2007. Beautiful Suffering: Photography & the Traffic in Pain. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2004. ‘In Around and Afterthoughts (on Documentary Photography’, Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, Michael. 2000. Traumatic Realism, The Demands of Holocaust Representation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, Michael. 2002. Between the Extreme and the Everyday; Ruth Kluger’s Traumatic Realism. In Extremities. Edited by N. Miller and J. Tougaw. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Serres, Michel, and Bruno Latour. 1995. Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time University of Michigan Press. Available online: https://archive.org/stream/MichelSerresAndBrunoLatourConversationsOnScienceCultureAndTimeUniversityOfMichiganPress1995/Michel+Serres+and+Bruno+Latour-Conversations+on+Science%2C+Culture%2C+and+Time+University+of+Michigan+Press+%281995%29_djvu.txt (accessed on 16 July 2018).

- Shanks, Michael. 2002. Towards an Archaeology of Performance. Paper presented at SAA Meetings, Birmingham, AL, USA, August 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Stear, Nils-Hennes. 2016. Edmund Clark and Crofton Black on the War on Terror. British Journal of Photography. August 1. Available online: http://www.bjp-online.com/2016/08/long-read-edmund-clark-and-crofton-black-on-the-war-on-terror/ (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Struk, Janina. 2004. Photographing the Holocaust. Interpretations of the Evidence. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja, Miriam Goheen, and Felicity Aulino. 2013. Radical Egalitarianism: Local Realities, Global Relations. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taryn, Simon. 2011. A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII. Berlin: Gagosian Gallery, Wilson Center for Photography, and Neue Nationalgalerie. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, John. 1998. Body Horror. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Ian. 1995. Desert Stories of Faith in Facts. In The Photographic Image in Digital Culture. Edited by Martin Lister. London: Routledge, p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Weizman, Eyal. 2014. Introduction: Forensis. In Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth. Edited by Forensic Architecture. Berlin: Sternberg Press, pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yenkin, Amy. 2014. An Ordinary Item Tells the Story of an Extraordinary Journey. Open Society Foundations. April 24. Available online: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/ordinary-item-tells-story-extraordinary-journey (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Zysk, Jay. 2017. Shadow and Substance: Eucharistic Controversy and English Drama across the Reformation Divide. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | For an extended examination of this image see (Laughlin 2016). |

| 2. | For a fuller discussion of both the reign of Maximillian and the nature of firing squads in Mexican revolutionary history, see (Noble 2010, pp. 78–98). |

| 3. | François Aubert was a French painter and photographer who had immigrated to Mexico, and soon became the semiofficial photographer to the new Imperial court and to the city’s middle classes. He evidently used his connections to attend the grim event, photographing the firing squad and Maximillian’s body in its coffin. Aubert’s photographs of the drama are perhaps better known as the source material for Edouard Manet’s series of paintings from 1867 to 69, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, depicting the moment when the riflemen’s bullets rip through the white shirt of the victim. |

| 4. | Ironically, the carte de visite format was popularised in Mexico by the Emperor himself, with images of him and his wife, Carlota, being circulated in advance of their arrival in the country. See (Noble 2010, p. 86) for a more extended account. |

| 5. | Frank Graziano defines contact relics or secondary relics as “objects or articles of clothing touched to the saint’s body or even the saint’s tomb and thereby imbued with the saint’s praesentia”. Like photographs, they thus became objects that “could powerfully displace holy presence across space and time” (Graziano 2015) See also (Zysk 2017; Tambiah et al. 2013). |

| 6. | The philosopher Arthur Danto, for example, argues that there are situations in which it “would be wrong or inhuman to take an aesthetic attitude, to put at a psychical distance certain realities—to see a riot, for instance, in which police are clubbing demonstrators, as a kind of ballet, or to see the bombs exploding like mystical chrysanthemums from the plane they have been dropped from” (Danto 2003, p. 22). Likewise, John Taylor has argued that “publishing images of the deaths of others is deeply suspect. What could be the motives of photographers who are in at the death, who may have stalked their prey like peeping toms with cameras, waylaying them only at the last and for the sake of a picture, voyeurs feeding a voyeuristic industry?” (Taylor 1998, p. 56). |

| 7. | Janina Struk points out the danger of revictimizing the victim in the scopophilic unease she feels in reviewing images of atrocity. Viewing photographs taken by the Nazis of the execution of Jews, she felt “ashamed to be examining this barbaric scene, voyeuristic for witnessing their nakedness and vulnerability, and disturbed because the act of looking at this photograph put me in the position of the possible assassin”. But she also felt that she had to do this, “as if the more I looked the more information I could gain” (Struk 2004, p. 3). Martha Rosler, in her influential essay on documentary photography claims that “Documentary, as we know it, carries (old) information about a group of powerless people to another group addressed as socially powerful” (Rosler 2004, p. 183). She argues forcefully that the focus has shifted away from the subject and onto the glorification of the imagemaker, and that the original honorable intentions of the “concerned photographer” have eroded over time into “trophy hunting” (Rosler 2004, p. 181), mutating the desire to effect change into the desire for personal satisfaction and success. She maintains that documentary photography “testifies, finally, to the bravery or (dare we name it?) the manipulativeness and savvy of the photographer” who “saved us the trouble” of personally being present in situations of “physical danger, social restrictedness, (or) human decay” (Rosler 2004, p. 180). See also Reinhard et al. (2007), Beautiful Suffering: Photography & the Traffic in Pain. |

| 8. | Gigliotti defines a “limit event” as an event or practice of such magnitude and profound violence that its effects rupture the otherwise normative foundations of legitimacy and so-called civilizing tendencies that underlie the constitution of political and moral community (Gigliotti 2003, p. 164). |

| 9. | For a useful account of the nature of traces and their relationship to photography, see (Hauser 2007). |

| 10. | This ability of the photograph to oscillate between past and present, to re-present the past into the present, is analogous to contemporary approaches to understanding time from a historical and archaeological perspective. The traditional historicist view that time is linear and progressive has been challenged by concepts of time as being folded, with moments connecting with each other across space and time rather than progressively one after the other (Seress and Latour 1995, p. 60). Time is thus interpreted as a fluid, interactive concept, a “river, forking, branching, slewing, slowing, rolling back on itself” or even a “crumpled handkerchief, in which apparently widely separated points may be drawn together into adjacency” (Shanks 2002). Similarly, Ulrich Baer argues that time is even more fragmented than this, and that rather than a linear narrative, “experienced time is also an attempt to acknowledge that for uncounted numbers of individuals, significant parts of life are not experienced in sequence but as explosive bursts of isolated events” (Baer 2002, p. 6). Butler concurs in this, maintaining that the photograph maintains a temporal projection that acts as a “kind of promise that the event will continue, indeed it is that very continuation, production and equivocation at the level of the temporality of the event: did those actions happen then? Do they continue to happen? Does the photograph continue that event into the future?” (Butler 2009, p. 84). |

| 11. | Many critics have elaborated on this developing genre of “Aftermath Photography”, or “Post Reportage” with David Campany claiming that photography is now a “secondary medium of evidence. This is the source of the eclipse of the realist reportage of events and the emergence of photography of the trace or ‘aftermath’” (Campany 2003, p. 27). Much of this work adopts aesthetics of observation and detachment, whilst others deploy an aesthetic that demonstrates the contradiction that the locations of atrocity are often simultaneously locations of striking visual quality. For an overview of the approach, see (Herschdorfer 2011) Also see (Walker 1995), and works by Ristelhuber, Seawright, Delahaye, and Sternfeld for examples of the genre. Many of these were gathered together in the exhibition at Tate Modern entitled Conflict, Time, Photography (2014). |

| 12. | I have explored these developments in more detail in (Lowe 2014). |

| 13. | These ideas are drawn from the context of the so-called “return to things,” “back to things,” and “turn to the nonhuman” that have appeared in the humanities since the late 1990s. Ewa Domanska explains that “In an attempt to reverse those tendencies, “new material studies” points to the agency of things, accentuating the fact that things not only exist but also act and have performative potential. Thus, in the “return to things,” it is not the topic that is new, but the approaches to things and the forms of studying them. (Domanska 2006, p. 339), See, for example, (Brown 2003, 2004), cf. also (Geismar and Horst 2004; Buchli 2002). |

| 14. | Other examples of this approach include the work of Gilles Peress, Gary Knight and Ziyah Gafic in the former Yugoslavia, again see (Lowe 2014). |

| 15. | Diane Zlatanovski describes a photographic typology thus “By definition, a typology is an assemblage based on a shared attribute. Patterns, both visual and intellectual, resonate and reveal themselves within collections. Information not apparent in isolation becomes visible in context—only through studying groupings are we able to discern similarities and contrasts. In observing collections of similar things, the beautiful variations become evident. And the closer you look, the more you see.“ http://www.thetypology.com/ABOUT-THE-TYPOLOGY. See Bernd and Hilla Becher’s visual typology of categories of industrial architecture for a photographic example of this approach. For one more directly related to the forensic turn, see (Taryn 2011). |

| 16. | In publicity for the book Clark explained the concept of control orders thus: “Control Orders were introduced under the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005. Between 2005 and 2011, 52 men suspected of involvement in terrorism were under Control Orders and subject to various constraints. These included the power to relocate them to a house anywhere in the country, to restrict communication electronically and in person, and to impose a curfew. ‘Controlled persons’ were not prosecuted for terrorist-related activity and the evidence against them remained secret. One man was subject to these controls for more than four years. Control Orders were replaced by Terrorist Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPIMs) in 2012.” http://www.herepress.org/publications/edmund-clark-control-order-house/. |

| 17. | In some cases the photographs were published along with interviews with the refugees, for example in the Telegraph Magazine, in other cases they were presented as a grid of images as in Newsweek where the captions presented the names and ages of their owners. |

| 18. | See (Levitt 2018). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).