1. Locating War Art within World Pictures

In 1928, Australian painter Will Longstaff’s celebrated large, black painting,

Menin Gate at Midnight (1927), toured Australia to stupendous acclaim and astonishing scenes of public reverence. The painting—immediately purchased and donated to the emergent Australian War Memorial—depicts the moonlit Menin Gate memorial that had opened in 1927, ten years after the horrific battles near Ypres in Belgium during which thousands of young Australians were killed or maimed. It represents the vision that possessed Longstaff during a night walk along the Menin Road in which he ‘saw’ (under ‘psychic influence’) the ghosts of the dead marching in endless lines (

McQueen 1979, p. 98).

But Menin Gate at Midnight neither conformed to traditional expectations that war art should depict acts of martial heroism or portray heroes, nor was it artistically experimental, by which we mean that, like almost all the Australian war art painted after World War One, it ignored the modernist art that had long been produced all across Europe and which, by 1927 and most famously in Weimar Germany, had resulted in savage experiments in form and language, triggered by the same horrors that had inspired Menin Gate at Midnight. This same modernist art would come to relegate works like Longstaff’s to deep storage, except in war museums (

Anderson 2012).

Longstaff’s fate could so easily have been shared by Iraqi war artist Dia al-Azzawi (born 1939) who might, until the 21st century, have been categorized as a mere adapter of Picasso. However, the wisdom of distance from New York’s hegemony permits space to absorb and appreciate the eclecticism of al-Azzawi’s great paintings of contemporary war, such as Sabra and Shatila Massacre (1982–1983). Indeed, his earlier works about conflict during the 1950s and 1960s, are arguably deliberate, abrasive and edgy, like New Yorker Leon Golub’s paintings from the same decades. They now seem as far from belated as Golub’s abrasive paintings of torturers and victims of the 1960s and 1970s, and both Golub and al-Azzawi have been similarly re-valued over the last couple of decades.

But we are now in the midst of an epochal transformation of the history of art and its canon, and two key facets of this are, first, the discovery that the story of modern art is global, not concentrated first in Paris and then in New York, and, second, the emergent definition of the succeeding period of art as contemporary. The ideas of modernism and postmodernism did not explain or communicate the changes that ensued from the end of the Cold War in 1989: the era of globalization, the spread of integrated electronic culture, the dominance of economic neoliberalism, the appearance of new types of armed and terrorist conflict, and the change in each nation’s place in the world. All of this suggests the emergence of a new cultural period, and not necessarily a better one (

Green 2001).

From this proceeds the contention that the new and controversial terms that located art as contemporary—terms that include place making, connectivity and, for our purposes most crucially, world picturing—override older distinctions based on style, medium, and ideology that had dominated art and art theory during the modernist period. This is, more or less, the argument that has been developed most influentially by Terry Smith and Peter Osborne, each framing the contention slightly differently (

Smith 2009;

Osborne 2013). But this is not all: the artists have come to understand that art during the contemporary period has been indelibly marked by the conditions of war around the globe, and this situation stretches at least back to WW1 and modern art. So how to proceed? Understanding and communicating war’s increasing centrality within both the modern and contemporary periods requires a new approach to both making art and writing: it requires a bottom-up approach to local art histories, defying the tendency of art history’s most senior international scholars to expect only derivative art in distant centres and who label it according to fixed ideas of how art would develop (i.e., the canonical textbook of the modern and contemporary periods).

Bois et al. (

2004) is guilty of this. Instead, we must seek out transnational, lateral contacts and resonances between artists and across borders, for this is the fact, not the exception, regardless of the fact that we seem hard-wired to think nationally in increasingly redundant silos (even as nationalisms surge again). As Reiko Tomii writes, “it becomes an important task for world art historians to seek out and examine linkable ‘contact points’ of geohistory” (

Tomii 2016, p. 16). She asks, how can we create transnational art histories that bridge the inevitable silo of national art history, connecting the local to the global? For a start, she answers, ‘It cannot be overstated that the more global we want to be in our investigation, the more local we need to be in our attention’ (

Tomii 2016, p. 15). Connections can be obvious, but the resonances that we can retroactively find have been all too often willfully dismissed as mere evidence of belated influence by arbiters at the metropolitan centre or their local apologists (

Barker and Green 2011). Instead, she offers the following method: ‘As a foundational tool, comparison of connections and resonances create contact points that puncture the established Eurocentric narrative’ (

Tomii 2016, p. 22). These would be, as she argues here, the building blocks of a world art history that is truly transnational. They require re-examining moments in art history and narrating them anew. We live in the period of contemporaneity, which has succeeded modernism, and through this revised lens we can now reassess the artistic potential of war art (and Longstaff) which the artists under analysis here have participated in.

Several other artists are of course addressing these concerns—Ben Quilty, Shaun Gladwell, Richard Mosse and many others—so within that larger, disparate and complex field we present our own projects as a microcosm of a globally-emergent theme, rather than through the normal curatorial and art-theoretical lenses—which are bounded by but strain at the edges of the discipline of art theory—of twenty-first century art. Working individually and collaboratively, the four artists discussed here have come together over the last few years to devise a sequence of projects that aimed to intervene in the discourse of contemporary art through the re-visualisation of war. They aimed to do this in disparate ways, and the variation of the results means that for this essay they refer to these projects and to themselves in the third person—he or she or they—even though the art historical understandings that the artists arrived at were shared. Furthermore, they deliberately eschew a detailed explanation of the topographies and iconographies displayed in their paintings and photographs, wishing to avoid the documentary role of illustrators and rejecting an artist’s inferior status to a writer. This is art. The works speak for themselves through their affect and resonance.

The artists wished to convert images of the vast battles, the battlefields and the memorial sites in which Australians fought 100 years ago, into works of art that would be unequivocally contemporary and that would communicate a different (and in a different way equally respectful) understanding of the significance of Menin Gate to that of Longstaff.

Their projects took, as it turned out, a deliberative, longitudinal turn. Instead of reifying the perspective that insists on the crucible of singular nationhood through war, they found a need for a longer and wider perspective that links the wars of 1917 to 2017 and which firmly placed Australia’s soldiers with their comrades from across what is now referred to as the global South—meaning sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, South East Asia, Oceania and South America, often colonized by European powers—including the hundreds of thousands of Indian troops who fought alongside Australians (men and women), and also their erstwhile foes. This is because the postcolonial and anti-colonial dimension of the great European World Wars has been an exciting dimension of war art, was often absent in its art histories, and was even largely ignored in post World War Two art histories until recently (

Enwezor et al. 2016). Pankaj Mishra, who chronicles the continuous history of anti-colonial movements across Asia from the 18th century onwards, brings together the panorama of many scholars’ research currently underway on the long history of anti-colonialism (

Mishra 2012). The four artists seized on and mobilized the artistic potential of two increasingly anachronistic methodologies that have been the technologies of historians and geographers, not artists. In summary, they began the process of constructing an atlas of global conflict in which Australia had been involved that links cause and effect from one theatre of conflict to another. Brown, Green and Cattapan made photographs and paintings across battlefield sites from the Vietnam War and ruined Australian bases in Vietnam, and worked at massacre sites together in Timor-Leste, which had been the site of an Australian-led United Nations intervention against retreating, genocidal Indonesian militias in 1996. That conflict, incidentally, had been the trigger for the reincarnation of the Australian Official War Artist program, reflecting long-standing Australian guilt about its responsibility for East Timorese suffering. In so doing, their project aimed to shift Australians’ understandings toward seeing a century-long and unmistakably global aftermath of war from WW1 to the present, for example in their jointly-authored large painting,

Scatter (Santa Cruz), 2014, which was based on photographs and watercolours, looking across humble graves at dusk, that the trio commenced in the Dili cemetery where Indonesia troops massacred Timorese students in 1993. The intention was to create images of contemporary war’s continuous duration. The painting took a wide and long historical context, taking into account Australia’s geographical and historical position in the globe’s South. This project would help re-imagine, according to the artists, Australia’s heritage of conflict and war by imagining its residues, traces and long-lingering ghosts; the visceral veil of red paint occluding the view of

Scatter’s graveyard does that. Through their reflective practices this group of painters is demonstrating that Australia’s war—even its war-like heritage—could now be re-interpreted not simply as a struggle to safeguard our shores—in portraits of soldiers or citizens—but as part of a complex, deeply connected global discourse where we, as Australians, would now re-cast ourselves as citizens of the ‘global South’ by visualizing the combinatory timelines of history that, added together, are a less-than-jingoistic and anti-nationalist portrait of Australian history. Through collaborative, practice-led research, and a more recent alliance with Gough, the artists seek to open up new perspectives on our national narrative within which the Western Front and 1917 begin to loom larger and larger.

2. Locating Practice within the Arena of Public and Museum Commissions

Jon Cattapan and Lyndell Brown & Charles Green (who have both worked together as one artist since 1989) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) share the rare and significant esteem of having been Australian War Artists. Brown and Green were deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq in 2007, whilst Cattapan’s tour to Timor Leste took place in 2008. Brown was the first woman to be deployed into a theatre of active war as an Australian War Artist. Paul Gough, a British painter and academic who moved to Australia in 2014, has a long association with the military. All four produce artworks (placed in national collections) and, as academics (at the University of Melbourne and RMIT University, Melbourne), reflect deeply (and publish widely) on the heritage of conflict and war by interrogating contemporary art’s representations of war, conflict and terror (

Brown and Green 2008).

Since the late 1980s, war museums, most notably the Imperial War Museum in the United Kingdom, began commissioning contemporary artists who moved beyond traditional expectations that war art should depict martial action and valour. Canada, New Zealand and Australia moved in this direction, though the United Kingdom has arguably the most well-established radical agenda, having commissioned artists such as Denis Masi (who in 1984 was the first artist-in-residence at the Imperial War Museum) and Stuart Brisley (residency in 1987), as well as those who work in teams, such as Langland & Bell (commissioned in 2002) and artist Yinka Shonibare’s collaboration with composer David Lang, commissioned to commemorate the great battles and tragedies of 1914–1918 (during 2018). Similarly, museums such as In Flanders Fields in Ypres have maintained an equally innovative agenda through a program of international artist residencies.

By 2007, following the reincarnation in 1996 of the Official Artist Scheme after a hiatus of several decades, the Australian War Memorial (AWM) began to commission art that was unequivocally contemporary and to seek art that ranged beyond traditionally observational painting. This commenced in 2007 with the commission of Charles Green and Lyndell Brown, (deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq), which incorporated mural-sized colour photography, and continued with the appointment of painter Jon Cattapan (to Timor Leste) in 2008, followed by video artist Shaun Gladwell in 2009, and moving by 2016 toward the idea of war art commissions by international artists, such as Turkish video artist Koken Ergun. Gough’s work has a similarly global reach and is in the permanent collections of war museums in the UK, Canada and New Zealand.

All four Australian artist-academics have been deeply engaged in contemporary debates on war art. Cattapan, Brown and Green are the only Australian-born academics within any Australian university to have worked as war artists, whether they are officially sponsored or not (

Green et al. 2015). Furthermore, the four artist-academics are also united by familial links with the military and are all implicated in complex webs of war: Green’s French grandfather was gassed and severely wounded on the Western Front in the Great War. In the Second World War his painter father was an army mapmaker, his commando-uncle was killed in battle, and his other uncle fought in Palestine and then in New Guinea. Cattapan’s father was an Italian soldier who hid at Castelfranco Veneto to escape German soldiers at the end of World War Two. Gough’s uncle was in a Royal Artillery battery that was evacuated from Dunkirk while he later served under General Slim in the Far East. Gough grew up in an extended army family based in British Empire garrisons across the UK, Europe and Central America (

Gough 2015).

This all adds up. It suggests that 1917 (and the Western Front) inhabits 2017, along with World War Two, and that the group of painters’ unexpectedly intense family experiences of war are potentially indexical of wider chronicles with world significance. This is the key framework that drives the painterly enquiry and its parallel contextual and critical framing.

3. The Practice: Works from Timor Leste, Iraq and Afghanistan Briefly Explored

As Australia’s 63rd official war artist, Cattapan joined a peacekeeping force in Timor Leste in 2008. During his period on commission the country was relatively stable, though security remained high and intelligence gathering continued apace. In accepting the commission there was a clear understanding that he was not in any way expected to proselytise on behalf of the Australian Defence Forces. Indeed, he was free to produce any art that he wished, just like Lyndell Brown and Charles Green the year before. Christine

Conley (

2014) writing on contemporary Canadian artists embedded within the Canadian military, has explained the same frank, free instructions to artists: the Canadian war art program, like the Australian Official Artist commissions, allows their artists to work freely without any requirement to produce work that represents the Canadian military in any specific or propagandistic way.

Instead, Cattapan was given license to explore contemporary soldiering through his particular predilections as an artist. This provided a rich and timely opportunity, which ultimately steered his aesthetics and social rationale for a decade. It also gave him an opportunity to interrogate ways of picturing surveillance:

I asked for and received access to night-vision technology, I found an extraordinarily simple but effective way to re-cast my work through those deep luminous fields of green and heightened figures captured in night-vision…

When you go out at night—and it’s very still and it’s very dark because there’s very little street lighting—there is this sense of the unexpected … this sort of slight anticipation … Those night vision goggles … had that glowing green look which automatically says to you surveillance, military … covert, potential danger.

Given that Timor Leste was a ‘low-tempo’ deployment, Cattapan was permitted to follow Australian soldiers on night patrol. Over time, during these clandestine activities he made sequences of photographs using a makeshift arrangement of camera and night-vision monocle. At times random, even haphazard, this investigative method resulted in a range of rich luminous images, deeply imbued with a sense of unease brought about by the limited field of vision that night vision goggles produce (

Brown et al. 2014). Reviewing the resulting body of photographs from Timor Leste, Cattapan confessed to being taken aback by the sense of imminent danger contained in those unearthly illuminations (

Johnston 2015).

This foreboding mood informed the cycle of paintings made on his return to Melbourne. The large and highly significant triptych,

Night Patrols, Maliana (2009), is a compendium work that conflates many of the patrols and nocturnal places into something of a spectral gathering. We see similar pictorial concerns addressed in the triptych

Night Figures, Gleno (

Figure 3). ‘The paintings in this series,’ one reviewer wrote, ‘are imbued with notions of anxiety and surveillance, and evoke in the viewer feelings of voyeurism and invasion of privacy.’ The soldiers are observers but are also being observed. As they roam the benighted villages they too are being scrutinised and followed by unseen eyes. Luminous and larger than life, the soldiers seem at odds with the unfamiliar land, with its uncanny vivid greens and tracery of dots and lines. Every effort at integration and communication seems to be frustrated by their very alien presence, accentuated by their virulent painterly difference (

Green et al. 2015, pp. 168–73).

For over twenty years, Cattapan has been evolving his painterly technique of dots and lines, trails, tracks and registration marks. They represent codes, maps, or systems of unknown data. In the ‘war paintings’ the spider web of lines were copied from contour maps of Timor-Leste and the nearby border country. This calligraphic language seems ideally suited to the heavily codified and calibrated space of the militarised landscape. Yet these rich paintings of Timor also speak of a tension between knowing and unknowing, hinting (as the curators of the Australian War Memorial acknowledge) at the ‘complex problems faced by peacekeepers as they try to communicate with people and integrate into their surroundings’. They describe a tense vision of potential danger and covert movement.

One year earlier, in March 2007, collaborative artists Lyndell Brown and Charles Green were embedded for six weeks in a succession of war zones across the Middle East, Afghanistan, and the Persian Gulf as Australian Official War Artists sponsored by the Australian War Memorial. There, in large, mural-sized colour photographs, they recorded the activities and experiences of the Australian troops in a range of military bases, which were often part of larger US operations and compounds.

Brown and Green have been creating paintings and photographic works together since 1989. Seizing this unique opportunity to collect and later paint images of contemporary history, they wrote of their encounters and impressions in Iraq:

We were looking for landscapes of globalisation and entropy. We thought this is what it must be like, and it was. Military bases are a study in grey and vastness. It’s worth remembering, of course, that we aren’t documentary photographers nor is that our task, even though our work might resemble that. We’re artists, and our only responsibility is to our own artistic conscience. Gradually, we know that other images from different times and places will creep back in. For the moment, though, this portrait of force, of the hard edge of globalisation, is what possesses us.

Their response to their period in and around the ‘front’ line was a suite of contemplative, realist paintings and, by contrast, painterly photographs of the paraphernalia and infrastructure of a nebulous new warfare—huge bases, hardware technologies, fleets of armoured vehicles, soldiers preparing for patrol. In one painting a troupe of American drone pilots high in the Afghan mountains proudly showed off their weird craft; in another a squadron of attack helicopters is neatly parked inside a huge compound, immortalized in

The Dark Palace 1, 2011 (

Figure 4). At the intersection of landscape, culture, and technology, these gravely quiet, almost frozen fragments of conflict were, as the artists noted, ‘a portrait of force, of the hard edge of globalisation’ (

Brown and Green 2008).

The enormous weight of military might, its unimaginable scale alongside the absence of a discernible front-line, combined with the numbing repetitiveness of the machineries of war, made a direct impact on their normal habits of representation. As a result, their method became to work with a near-documentary objectivity, creating what appeared to be ‘neutral’ photographs of silence and stillness, and a suite of literal and extremely austere paintings.

The entire cycle of paintings, prints and photographs shows Brown and Green tending toward unconnected vignettes, sequential formats, and a near-static sense of display. However, the compositions are never single-dimensional. Superimposed and lain over their strange configurations are the cultures and histories at the heart of the conflict. There is a significant discourse that explores the topographies of emptiness in militarized spaces. Gough has explored this phenomenon in his paintings, publications and recent photo-montages, tracing its articulation beyond 1918 when the British writer Reginald Farrer stared across the lunar face of No Man’s Land and recognised that it was wholly misleading to regard the ‘huge, haunted solitude’ of the modern battlefield as empty. ‘It is’ he argued, ‘more full of emptiness… an emptiness that is not really empty at all’ (

Farrer 1918, p. 113).

Several painters, most famously Paul Nash, adopted and extended Farrer’s reading of the new face of war, and posited the notion of a ‘Void of War’ as a means of re-determining the inverted spatiality of the modern battlefield. Nash and others embraced this spatial inversion: populating its emptiness with latent violence, marveling at its awesome potency, and depicting it as a place haunted by sublime qualities. (

Gough 2017) As Brown and Green had seen in Iraq, the militarised terrain is not so much a landscape as the same, uncanny ‘paradox of measurable nothingness’ of World War 1 (

Weir 2007, p. 43). ‘Our aim’, they have written, ‘was an apparent neutrality and objectivity as the means for creating a powerful vision of overall clarity and focus (but not necessarily the truth) in the midst of chaotic ruination’ (

Green et al. 2015, p. 170). This aim is manifest in very recent collaborative paintings such as

Spook Country (Maliana) (

Figure 5). In contrast,

Afghan National Army Perimeter Post with Chair, Tarin Kowt, Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan, 2007–2008 (

Figure 6), shows a guard post at the edge of an enormous base in the mountains of southern Afghanistan. The photograph was taken in late afternoon with raking, warm light throwing the scene into sharp focus. But the view is one of highly composed decay and entropy: a guard post made of old shipping containers; broken office chairs like sculptures atop the containers; jagged blue mountains from which the Taliban probe the base’s edges; a war zone out of control that was to revert to Taliban control the moment that Western troops evacuated a few years afterwards.

Few have defined the diffuse spatiality of the post-modern battlefield better than Australian War Memorial curator Warwick Heywood:

Brown and Green’ s abstracted, ruined world represents the obscure dimensions of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts that exist between globalised, military systems, severe landscapes and frontier mythology.

“It is”, he continues, “a highly complex and imaginary realm that is echoed in the larger political, operational and technological dimensions of these obscure, but omnipresent, wars.” And wars whose genealogy goes straight back to World War One, when many of the artificial colonial borders now ignored within war zones were created. In 2017, Brown and Green were approached for another commission: to create a large tapestry woven by the Australian Tapestry Workshop (ATW) for a new Sir John Monash Centre, at Villers-Bretonneux, in northern France, to commemorate Australian involvement in the tragic battles of the Somme. Their vast tapestry,

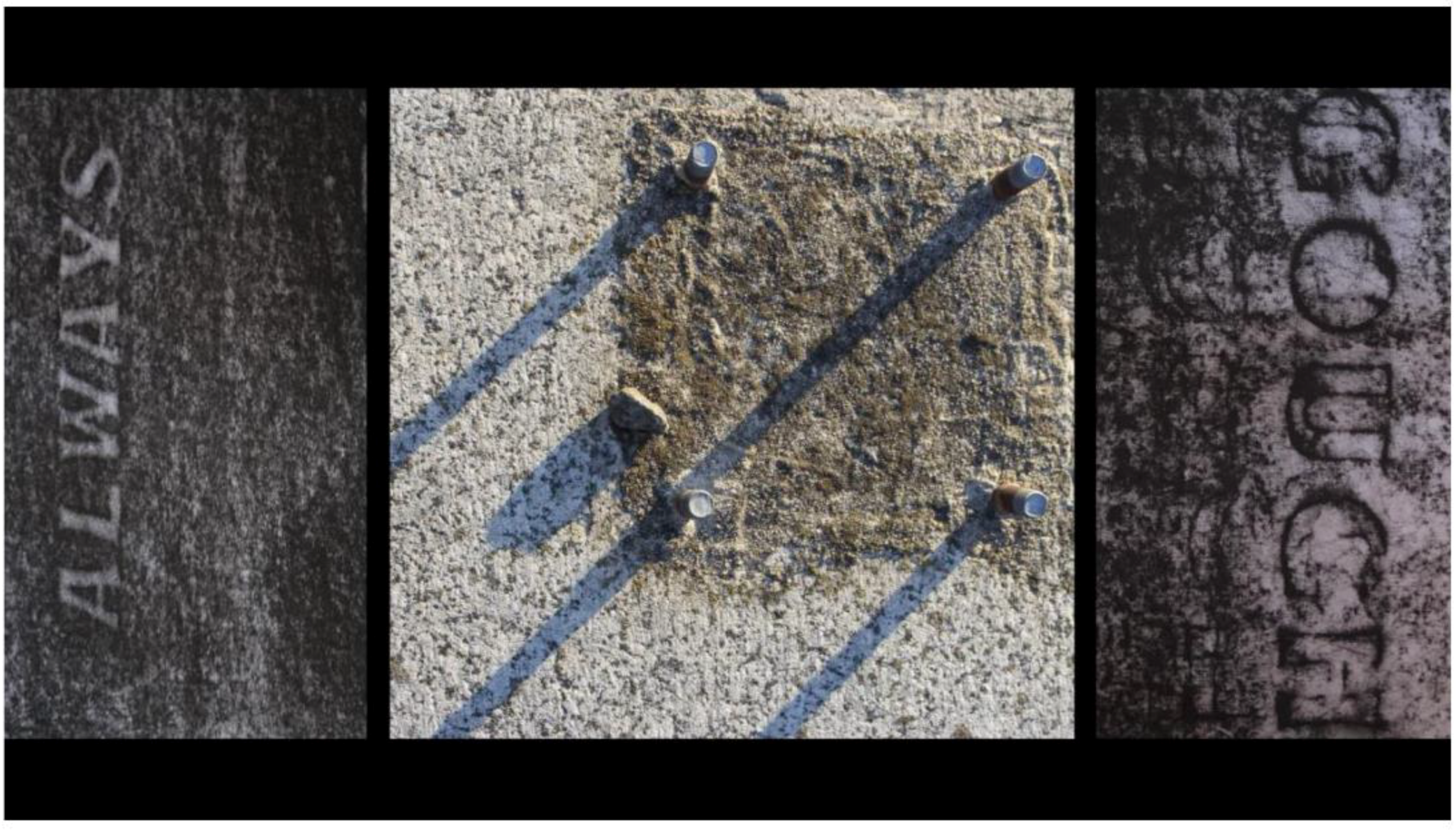

Morning Star (2017), evoked the experience of arrival at a war and, in particular, of young Australians reaching the Western Front. With them were their memories of Australia and their departure from home. Rather than duplicate the powerful archaeology of war at the Centre and at museums across the region, including at Thiepval and La Peronne, the work they prepared evoked the soldiers’ pathway to the Front, emphasizing the incongruity between the Australia that they remembered and their journey closer and closer toward the ruinous trenches. It seems to the two artists that it was essential, first, to conjure a remembered place of freedom and clear light—a nearly-monochromatic early morning misty bush landscape—and, second, to evoke the sea-borne passage leading to the soldiers’ arrival at the Front, in two collage constructions composed of old photographs, splayed across the dawn scene and all translated into the pixilated remove of tapestry. Casting an eye back to early twentieth century wars, Gough’s drawings address both the spatiality of commemoration and the epic emptiness of the former battlefields across Europe and the Mediterranean. His recent works, completed since his arrival in Australia, recorded the decrepit and abandoned British army bases in former West Germany where he and his family were garrisoned during the Cold War, and speak of an abjectness and blankness which chimes with fellow painters' concerns. Using

frottage, rubbings and photographic collage, Gough has assembled a suite of triptych forms drawn from prolonged site visits (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The suite forms a visual parallel to the litany of memorial forms devised in 1917 by Sir Edwin Lutyens, which he described as a ‘stoneology’, a list of shapes, dimensions and textures that he thought might capture the fabric of memory, and which he consolidated into a four-square ‘War Stone’, or ‘Great War Stone’ that later morphed into the less severe Stone of Remembrance, which perhaps more aptly illustrates his intention (

Geurst 2010, p. 22).