1. Introduction

How did a photograph of a refugee basketmaker published in

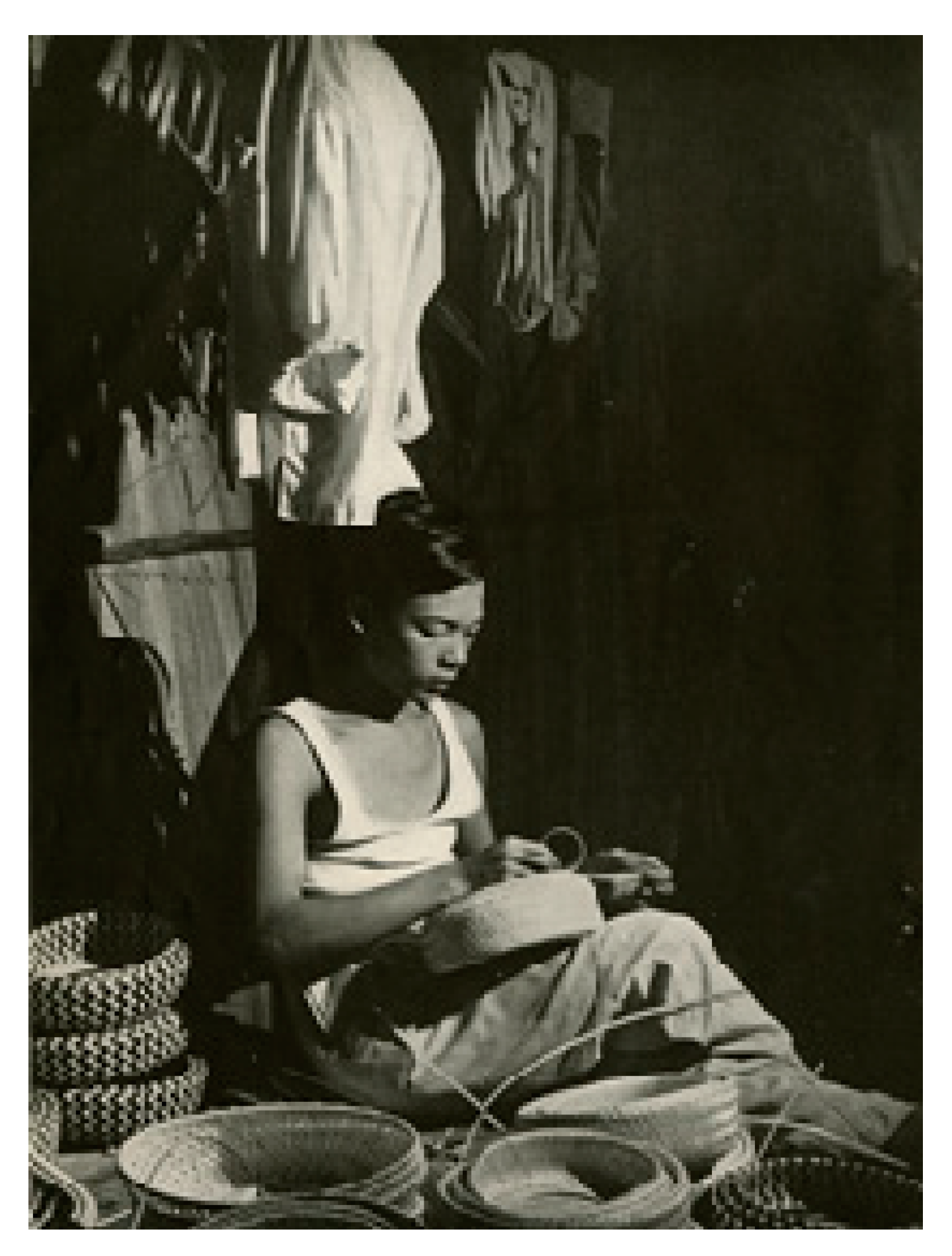

Interiors magazine during 1956 support American Cold War efforts in South Vietnam? The photograph in question depicts a young artisan sitting alone on the ground making a basket at the Xom Moi Refugee Camp north of Saigon (

Figure 1).

The photograph belongs to the period when South Vietnam enlisted the United States to help with refugee resettlement. Curiously, however, it lacks elements found in other photographs representing Vietnamese artisans featured in the same article of

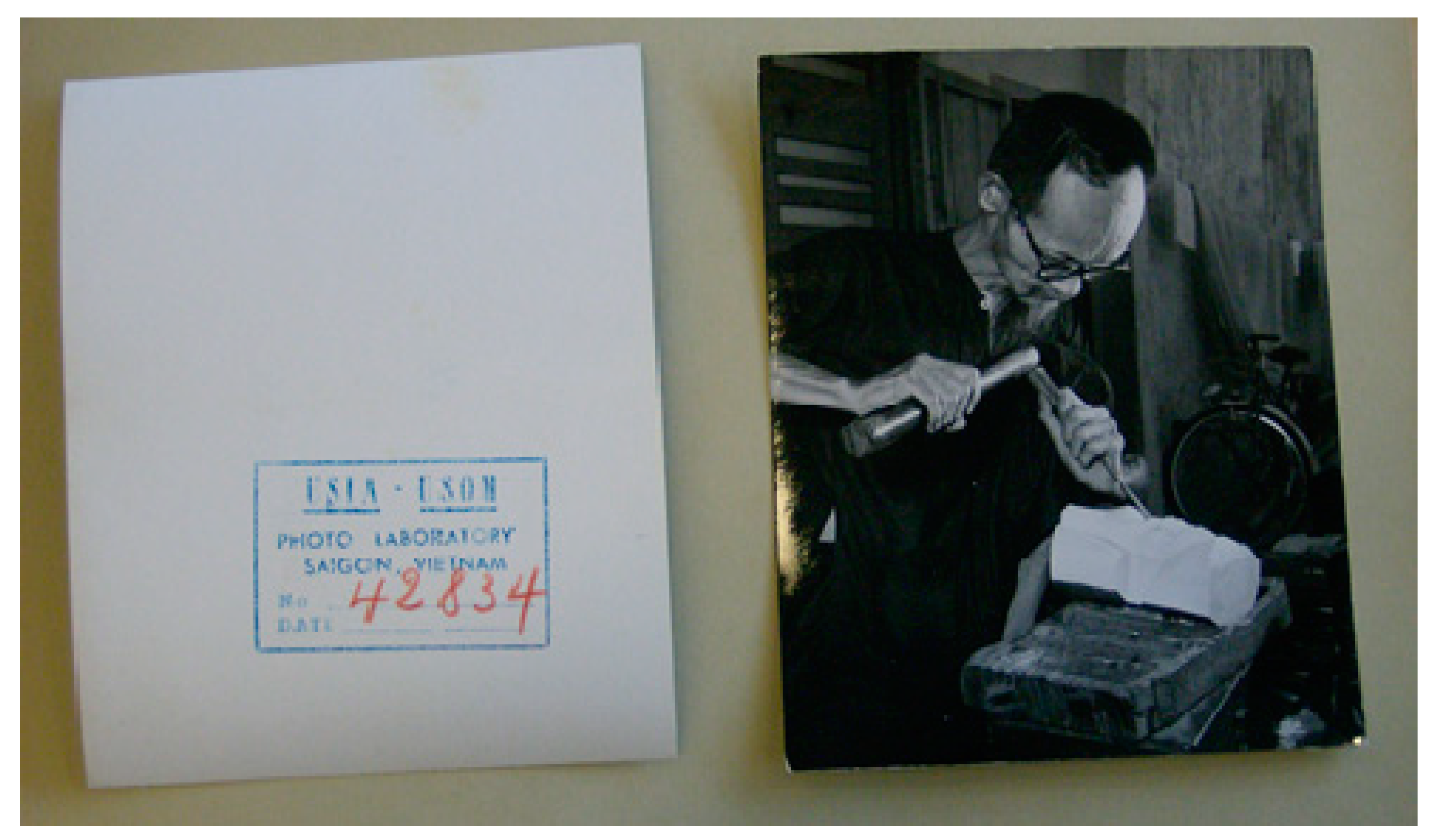

Interiors magazine. For example, another photograph depicts an artisan whose moustache, goatee, and receding hairline suggest he is older than the basketmaker mentioned above (

Figure 2).

In addition, he wears glasses and a shirt in a photograph that captures his intense concentration as he carves a sculpture. Interestingly, the background of this photograph suggests that the artisan had access to an environment beyond his workspace. Behind him, a bicycle leans against the wall not far from what looks like an opening to another space. In comparison, the basketmaker appears young and less physically active. The velvety black background of the photograph obscures any references to the way his immediate environment connects to other spaces.

During this period, accounts of refugee artisans published by the State Department sometimes featured images of groups of artisans. In 1956, for example, the United States Operations Mission in Vietnam authored a report illustrated with photographs of refugee artisans seated on the ground weaving mats indoors as well as preparing weaving materials outdoors. The caption points to American support for their endeavors: “The third phase of the refugee program was assistance in helping them become self-sustaining” (

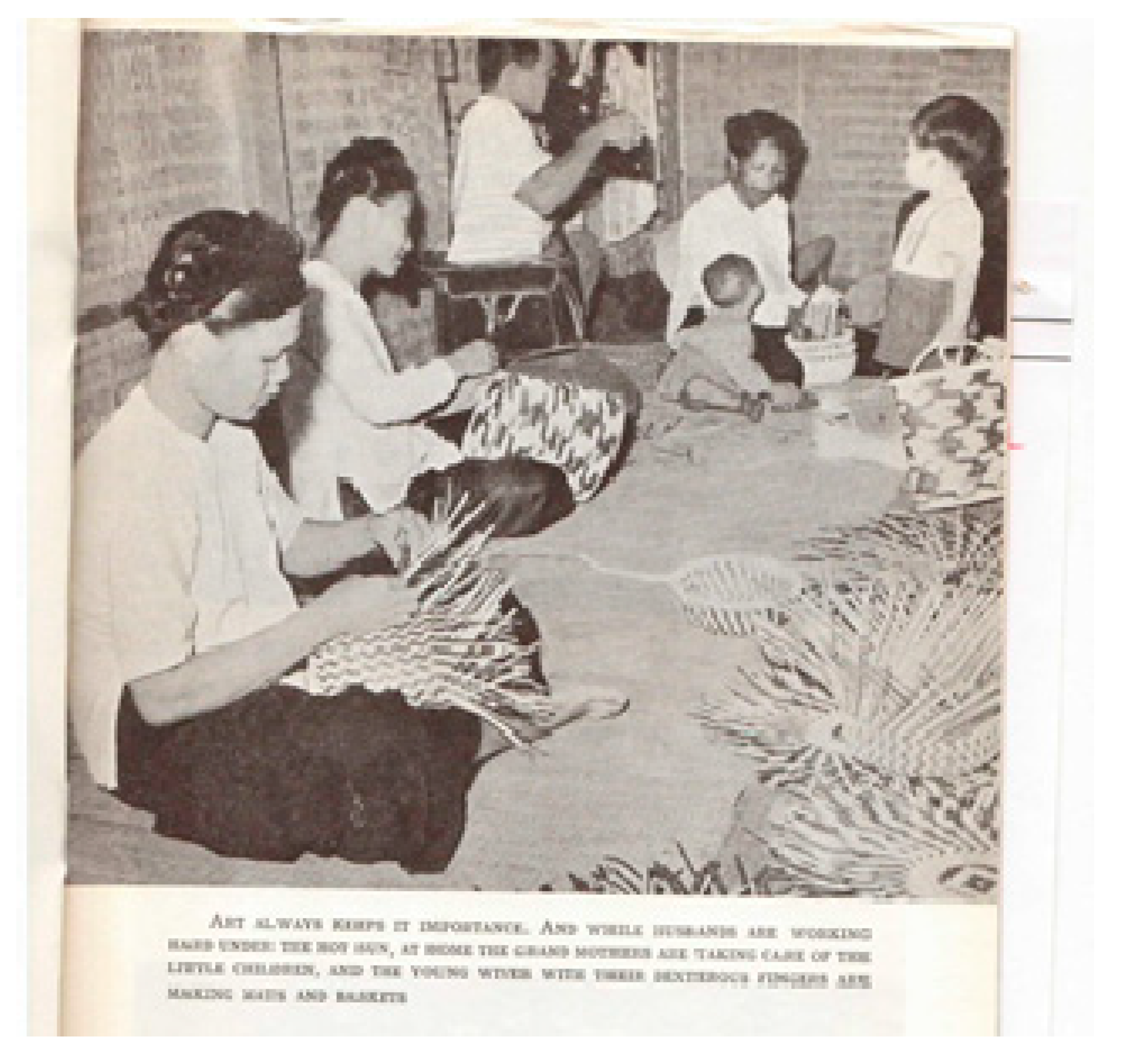

USOM 1956, n.p.). The South Vietnamese government was also publishing English-language material depicting artisans. A booklet touting the contribution of American aid in developing the Cai-San resettlement village included a photograph of women weaving baskets indoors (

Figure 3). The caption spoke of gendered craft production and cross-generational harmony (

Cai-San 1956, p. 17).

The photograph of the basketmaker stands apart from this type of image and from the photograph of the man carving. The basketmaker appears alone in a carefully composed and dramatically lit space that reveals few details about his location. While the basketmaker’s body is framed to give visibility to his weaving, he appears physically less active in practicing his craft than artisans in the other photographs. Additionally, he looks younger than most. Surrounding the basketmaker are a number of unfinished and completed baskets. Neither the photograph of the sculptor, nor the photograph of artisans that the United States Operations Mission published or the photograph of women at Cai San, depict completed works of craft. Further, the activity of the older artisan carving suggests noise, as does socializing by the women weaving mats at Cai San. In contrast, a quiet stillness envelops the basketmaker’s isolation.

Interestingly, both the quiet mood and the basketmaker’s isolation contradict the reality of his life in a refugee camp. Historian Ronald Bruce Frankum observed that at one point the Xom Moi camp held over 8000 refugees (

Frankum 2007, p. 171). Therefore, for most of the time the basketmaker was probably not alone in the camp. The realization begs the question why an article about American industrial designer Russel Wright’s and his team’s activity in Southeast Asia begins with a full-page photograph of a basketmaker that ignores elements of his reality and departs from other contemporary photographs of refugee artisans working in South Vietnam. What, and for whom, does the image signify? In what follows I explore these questions by reviewing the purpose of American activity in Vietnam during the 1950s, including the establishment of photography there as part of U.S. Cold War efforts aimed at promoting security and economic development. Importantly, some of this photography was intended to circulate in the U.S. and in particular, the basketmaker photograph resonates as what Laura Wexler refers to as a “domestic image” (

Wexler 2000, p. 21). As published in

Interiors, the photograph referenced the plight of northern refugees in the south while it elided direct references to civil war there and to American concerns about refugees’ potential political leanings. Instead, the photograph shaped the image of the refugee artisan to aid in entreating the American private sector to import his craft.

2. The United States in South Vietnam, and South Vietnam in the United States

Wright saw this photograph and others depicting refugee artisans installed during January 1956 as part of a display of Vietnamese craft organized for him and his colleagues at the Saigon Chamber of Commerce (Russel Wright Papers Box 45

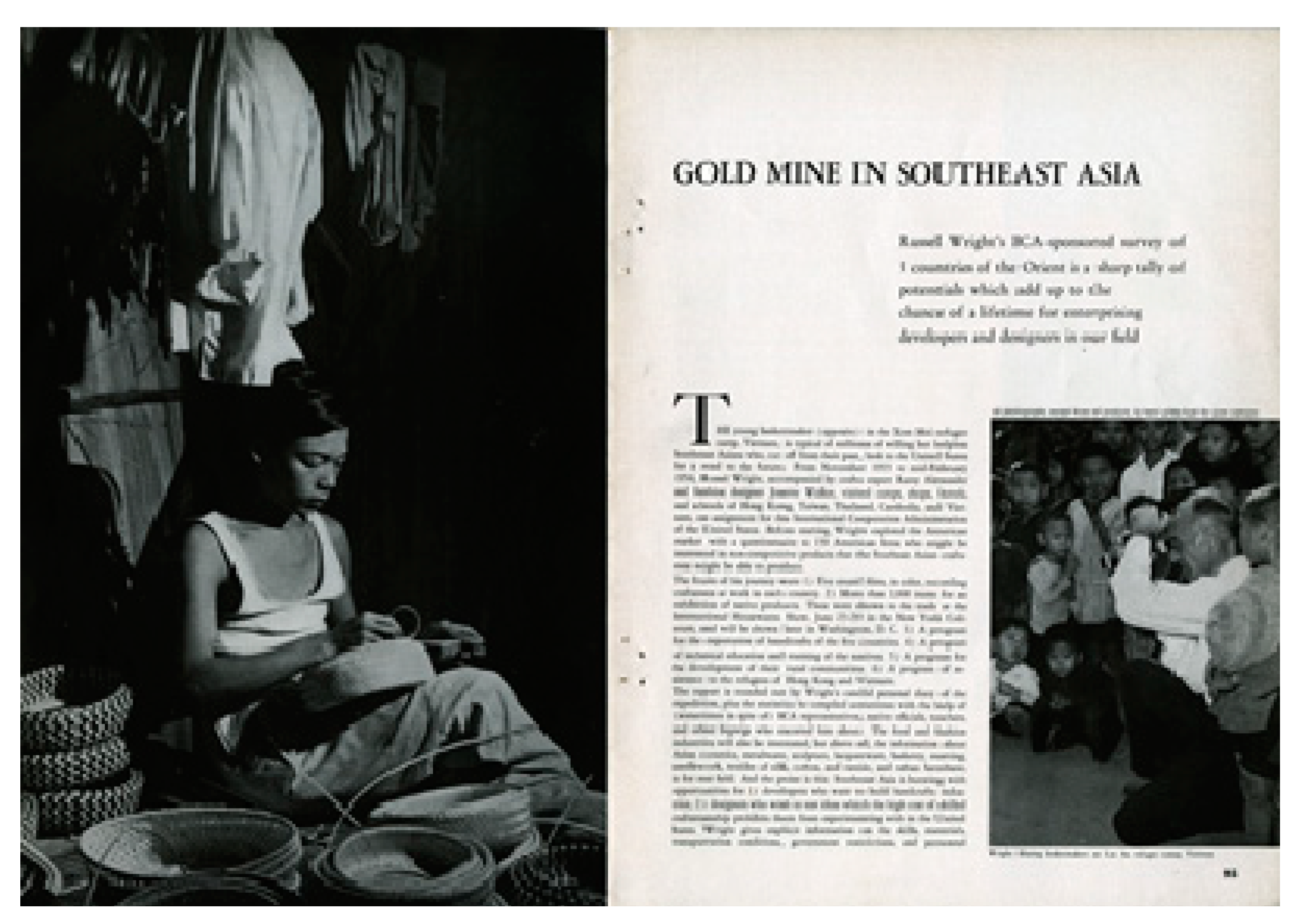

1). Eight months later, the photograph of the basketmaker featured on the first page of an article published in

Interiors magazine. The article reported that Wright was overseeing an American State Department-led craft export program in Southeast Asia (

Wright 1956) (

Figure 1).

The photograph likely originated prior to 1956. By 1952, Houston photographer Everette Dixie Reese had established the Photo Lab for the United States Information Agency-United States Operations Mission in Saigon [USIA-USOM] (

Smith 2011, p. 38). President Eisenhower launched the USIA in 1953 to administrate information about the United States distributed overseas. Also established in 1953, the United States Operations Missions served as an umbrella to implement technical support as well as economic, health, infrastructure, and educational development aid that was issued through the Foreign Operations Administration, which the State Department oversaw to coordinate security and economic relations mainly through trade in the Free World (

Record Group 469 1953). Leland Barrows, who served as the director of USOM Vietnam from 1954–58, likened these efforts to “the cost of maintaining peace through giving aid” (

Barrows 1959, p. 674).

In Saigon, Reese and his colleagues in the Photo Lab printed images for distribution locally and for the U.S. Army and additional official governmental agencies.

2 Additionally, the Photo Lab worked with the graphics section of USOM in Saigon preparing “posters, maps, training manuals, brochures, briefing documents, quarterly reports, self-help education material, etc.” along with “art preparation and the layouts used in support of USOM divisions” (

USOM 1954, p. 60). Reese’s staff included Henri Gilles Huet, whom the

Interiors article credits with taking the photograph of the basketmaker. Reese, Huet, and other photographers affiliated with the lab recorded the civilian population and environment of Vietnam. It was their activity that probably generated Huet’s photograph of the basketmaker and other photographs of artisans published in the article about Wright.

In drawing attention to photographs of northern refugees in South Vietnam this essay focuses on the period from 1954–56 because then, as non-military technical specialists went overseas on behalf of the State Department, the American press and these specialists published their activity in Vietnam and Southeast Asia for Americans at home. American State Department’s attention to refugees in Vietnam escalated with the signing of the Geneva Accords in July 1954. Photographs of refugees migrating south began appearing in U.S. media during a key period of migration that followed between August 1954 and May 1955, when people could regroup on either side of the 17th Parallel that ultimately would divide the South from the North (

Gregory et al. 1957). The United States recognized South Vietnam, the Republic of Vietnam, as the authentic Vietnam and established close relations to support its President Ngo Dinh Diem. In contrast, the United States did not formally recognize the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or North Vietnam, which contended that Vietnam emerged from colonialism as a sovereign, autonomous state in 1945. In 1954, it would claim to be the legitimate nation of Vietnam.

The United States was not pursuing its own settler colonization in Vietnam. However, with the intensification of the Cold War throughout Southeast Asia, the State Department identified native craft as a means to link South Vietnam to the Free World as part of its efforts to economically engage the country with American interests and support. The United States was supporting the new nation militarily and with technical aid aimed at resettling the nearly one million refugees from the North. As part of its aid efforts channeled first through Foreign Operations Administration (FOA) and then through the International Cooperation Administration, the State Department contracted Wright and his firm, Russel Wright Associates (RWA) to survey craft production in South Vietnam, report on their findings, and develop as well as implement an export program that adapted Vietnamese craft to U.S. middle-class tastes in home furnishings and fashion accessories. In fulfilling this remit, RWA would have to persuade American importers, business owners, and distributors as well as fellow design professionals that Vietnamese craft was desirable and available. To facilitate this task, Interiors represented the basketmaker to a U.S. readership as needy, deserving of aid, and expecting to follow American guidance in producing craft for export.

In the larger context, the State Department was assuming the role of the strong partner in a diplomatic relationship (

Said 1978, p. 40) in part by identifying which facets of Vietnamese life should remain pre-modern, if not largely unchanged, yet requiring rescue. In other words, the United States was defining how refugees in South Vietnam mattered for its own goals of bringing South Vietnam into the Free World. The process echoes Liisa H. Malkki’s observations about the ways refugees are created discursively, for example, in knowledge domains such as anthropology and foreign relations, and through developments in capitalism and international relations (

Malkki 1995).

An Orientalist impulse wove through these American discourses of Vietnamese refugees. Edward Said had outlined how, as nineteenth century imperial Europeans constituted the significance of their colonized Middle Eastern subjects, they gave themselves greater power, authority, and agency by associating with progress and change as they also removed their subjects from historical time or development (

Said 1978). Cultural historians Douglas Little and Christina Klein respectively analyzed American Cold War interests through the lens of this theme in Said’s

Orientalism. Little focused on images from the Middle East that circulated in

National Geographic (

Little 2002, p. 10), while Klein shifted the location of Orientalism from Europe and the Middle East to the United States and Asia (

Klein 2003). According to Klein, during the early Cold War, American cultural producers created narratives about Asia and the Pacific organized around “integration—international and domestic” to facilitate the “forging of bonds between Asians and Americans both at home and abroad” (

Klein 2003, p. 16). Nevertheless, these bonds shaped representations of Asians to the interests and desires of middle-class American consumers of popular entertainment.

Klein’s work throws into relief some of the power extending from the American State Department to its burgeoning aid programs staffed by contracted, non-state agents charged with shepherding Vietnam towards a democratic government after 1954. Not unlike European governments and private concerns sending forth representatives to discover and get to know “Orientals”, the State Department supported RWA and other Americans in surveying, analyzing, evaluating, and reporting on artisans and their craft in Southeast Asia. These Americans worked under the belief that their endeavors would improve the lives of needy people residing in South Vietnam, especially those who recently arrived from the north (

Slide lecture 1960, Box 38). At the same time, concerns about the vulnerability of Vietnamese craft to rapid modernization and unchecked industrialization (

McLaughlin 1958, p. 37;

Russel Wright Papers 1961, Box 38) were being explored in studies supported by the United Nation’s Economic Council for Asia and the Far East and in related publications by

Schaff (

1953) and Theodore

Herman (

1956).

These beliefs and concerns intersected in photographs of artisans and craft in South Vietnam. As an example, the photograph of the basketmaker conjured a vulnerable yet productive subject meant to appeal to Americans who might be interested in importing and merchandising foreign craft. Its existence was made possible by American government officials and diplomatic officers as well as military aids supporting their nation’s national security and economic interests in the region along with troops from France and Great Britain that assisted with refugee migration southward. However, the photograph avoids showing Americans at home the Americans who were carrying out these interests in Vietnam or political strife ongoing there.

On this point, the photograph has a lineage in American culture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Drawing upon what Anne McClintock shows are etymological links between the verbs dominate and domesticate (1994), design historian David Brody suggests that as the U.S. coupled its aims for overseas expansion with notions that it was spreading American democracy and progress to more of the world (

Brody 2010, pp. 48–50), upper middle-class Americans incorporated Asian artifacts from these places and American copies of them into their homes as part of a “civilizing trope” that elevated their cultural status and, by extension, the Asian people who made them. Photographs contributed, too, like the ones Frances Benjamin Johnston made of Admiral George Dewey and his men who became famous for their violent, rapid routing of the Spanish navy in the Bay of Manila early in the Spanish–American War. In Johnston’s photographs, the men’s poses, settings, and activities helped to “make the visible [traces of imperialism] disappear” (

Wexler 2000, p. 35) by conveying the decorum, civility, and sentimentalities familiar in life at home for white middle-class Americans.

Although the basketmaker photograph likely was made possible by the diplomacy and military aid efforts that preceded its creation in Vietnam, also, the photograph “signifies the domestic realm” (

Wexler 2000, p. 21). With obvious references to diplomacy agendas, civil war, and violence out of its frame, the photograph addressed the basketmaker to the home front of the Cold War by promoting a maker for new items for interior furnishings. The photograph underscores its status as a “domestic image” (

Wexler 2000, p. 21) further by presenting a subject appearing to need looking after and, discursively, who deserves such a response from Wright’s peers in the home furnishings industry. It was their opportunity to accept Wright’s invitation to forge a new trade pathway linking Vietnam and the U.S. and thereby ostensibly raise the basketmaker’s standard of living and hopes for a better future.

3. Pathos

English-language publications about Vietnamese migration portrayed southbound northerners as agents for freedom and as people suffering in its pursuit. The State Department claimed that northerners were self-motivated, ambitious people. They chose to forego “being placed under the Communist yoke, [and they] are moving outward to Free Viet-Nam”, where they could farm and “work out new lives in freedom” (

Department of State Bulletin 1954, p. 337). Correspondingly, the U.S. Navy labelled its participation in Operation Passage to Freedom as Operation Exodus while the U.S. distributed funds to help integrate northerners in their “new lives” in “Free Viet-Nam” (

Department of State Bulletin 1955, p. 224). However, despite the importance of the religious network led largely by the Catholic priesthood, the agency of these migrants depended largely on U.S. aid and in early August 1954, the State of Vietnam requested the help of the United States in resettling them (

Elkind 2014). A year later,

National Geographic reported on these efforts by representing northerners as a collective “human tide” awaiting the U.S. “Freedom Ships” docked near Haiphong in the Gulf of Tonkin (

Samuels 1955, p. 864). The cover of the Catholic publication

Resettlement of the Refugees of North Viet-Nam, proclaimed, “The Refugees fled for the sake of their Faith.” The publication noted the effects of American aid on refugees and classified them according to their Protestant, Buddhist, or Catholic beliefs. Adopting Western biblical narratives shared by the name of U.S Navy’s Operation Exodus for its contribution to Operation Freedom, the publication’s vocabulary evoked the migration of the Jewish people in their struggle to leave enslavement in Egypt to bond as a nation in the Promised Land. Among the million refugees fleeing the North during 1954–1955 some two thirds were of the Catholic faith, and the caption of a photograph which showed people crowded onto a small vessel described their migration as “The beginning of the Exodus” (

Pham Ngoc Chi 1955, p. 1).

Attention to the difficulty of refugee migration also surfaced as a characteristic of refugees suffering because they had left their homes under trying circumstances and they experienced difficulty

en route to the South as well as upon their arrival there. Lt. Tom Dooley’s publications as well as popular literature emphasized refugee suffering. In Dooley’s first book,

Deliver us from Evil, The Story of Viet Nam’s Flight to Freedom, black and white photographs show refugees in North Vietnamese processing camps where Dooley treated their illnesses before they migrated south. One in particular focuses on the children of women whose husbands had been “slaughtered in the eight years of war” between the French and the Vietnamese (

Dooley 1956, p. 96). Others depict mothers and grandmothers with children blankly staring at the camera. Elkind says that Dooley’s publications helped to galvanize U.S. policymakers and the American public in support of American intervention in Southeast Asia (

Elkind 2014, p. 996).

The New York Times among other publications published a photograph of refugees in crowded, makeshift conditions (

Samuels 1954, Sm11) while other articles examined additional problems. For instance, some refugees were placed on land reclaimed from local warlords or rebuffed by locals who would not welcome or integrate them (

The Christian Science Monitor 1956, p. 4).

Catholic-sponsored publications such as

Resettlement of the Refugees of North Viet-Nam stopped short of stating outright that refugees were being persecuted on religious grounds. Nevertheless, their representations of refugees as innocents compelled to leave their homeland may have helped to persuade fellow Catholics to support the State Department’s aid to northerners arriving in the South. After all, Americans would also remember the hardships of refugees migrating before “advancing red” communist forces in Korea, just a few years earlier (

Ellis 1950, p. 9). Interestingly, underscoring the hardship of migration may have deflected attention from internal conflict that, in South Vietnam, saw the government forcing the movement of Montagnards, or “mountain people”, to free up their ancestral lands for resettling northerners.

At the end of the 1950s, in “We Strangers and Afraid, The Refugee Story Today”, Elfin Rees situated Vietnam in a broader migration discourse, claiming, that “this is the Age of the Uprooted and the Century of the Homeless Man” of which “900,000 homeless came from the territory of the Viet-Minh” (

Rees 1959, p. 3). In

Interiors, the gravity of losing roots and becoming homeless colors the article that follows on from the first full page that features the young basketmaker. The photograph’s dramatic angles and black and white contrast as well as the basketmaker’s location in a corner, contribute to underscoring his loneliness, to which the very beginning of the article attests on the adjacent page: “The young basketmaker in the Xom Moi refugee camp, Vietnam, is typical of millions of willing but helpless Southeast Asians who, cut off from their past, look to the United States for a road to the future” (

Wright 1956, p. 95). The photograph and text amplify the artisan’s vulnerability by rendering him anonymous. Darkness shrouds him, reifies his separation from a community and underscores what Americans perceived as social, economic and political vulnerability that could possibly compel him to seek aid from communists.

As Peter Gatrell, a historian who studies migration and refugees of the twentieth century realized, “the unnamed individual embodies the condition of refugees everywhere who cannot avoid their amalgamation into a collective category of concern” (

Gatrell 2013, p. 10), reminding us that any suffering conveyed in the basketmaker’s photograph, was likely aimed for reader affect concerning this “category of concern.” In addition to treating the basketmaker as a representative of millions of refugees, the word “helpless” and the phrase “road to the future” in

Interiors, associate him with the anxiety of the State Department on the prospect of resettling so many refugees who seemed helpless, and suggest that taking on this task constituted a problem for Americans to resolve by providing refugees with a pathway to the future.

In studying the publication of photographs of refugees in Britain that supported the pro-Republican cause during the Spanish Civil war, Caroline Brothers inquired about the purpose of showing suffering and further articulating it through captions. She referenced Allan Sekula by claiming that these photographs of refugees mobilized compassion and pity for their subjects instead of compelling readers to pursue collective struggle to change the underlying reasons why people became refugees in the first place. Furthermore, according to Brothers, their “refugee passivity” rendered these subjects dependent on “the ministrations of foreign authorities” (

Brothers 1997, pp. 159–60). Correspondingly, the composition of the first two pages of the

Interiors’ article depicts the basketmaker as passive in comparison to Russel Wright, director of the American State Department-led craft aid program. The refugee’s photograph denies him any visible, active struggle regarding his loneliness and homelessness, and it affirms his status as a representation of hundreds of thousands of others who ostensibly await help from the Americans. In comparison, across the page Wright appears active; his photograph shows him filming as refugee children look on (

Figure 4).

In other words, the first two pages of the article contrast the artisan in the refugee camp, sitting alone, quietly working, with the aid figure’s mobility in traveling to South Vietnam to record the basketmaker’s skills and, subsequently, to serve as their spokesman on behalf of the American design industry. Their relationship speaks to the designer’s agency to move, see, know, and communicate, in contrast to his subject’s disempowerment. It also speaks to the refugee artisan connoting pathos in regard to which the designer takes action and does so perhaps to model for American readers at home that a response to the refugee, of doing something, is called for.

Wright also stands in for and guides the aspirational tastes of the American middle class whose expansion into suburbia coupled its whiteness with its increasing property ownership and need to decorate new homes. This latter activity generated an American iconography of race and class in its “configuration, décor, possessions, and maintenance” (

Harris 2003, p. 21). Wright and his wife Mary even wrote a book about organizing the many possessions that were soon cluttering American homes (

Wright and Wright 1950). These homes and the fashions into which white Americans would absorb Vietnamese crafts ranged from the middle to the upper classes. This was evident in the stores that Wright approached to import craft, which ranged from Lilly Dache and W and J Sloane in New York and upscale department stores in other urban centers at the higher end of the range, and Sears, Roebuck at the other. Without necessarily realizing it, Americans would look at, shop for, and purchase Vietnamese craft initially made by refugees who lacked a permanent home and whose resettlement would be vitalized by American consumption for home and self.

4. “The Refugee Problem”

The photograph of the basketmaker also served American interests by casting the artisan as a problem that belonged to a larger narrative in which the United States identified who counts as a problem and determined, or helped to determine, the criteria by which the problem would be resolved. American art historian Linda Nochlin offers a glimpse of this narrative which continued beyond the 1950s, stretching into the years of the Vietnam War. In 1971, writing about the marginalization and erasure of women from art history, Nochlin touched on U.S. attitudes towards non-white America, the Global South, and Asia. “We tend to take it for granted”, she pointed out, “that there really is an East Asian Problem, a Poverty Problem, a Black Problem and a Woman Problem. But first we must ask ourselves who is formulating these ‘questions,’ and then, what purposes such formulations may serve” (

Nochlin 1971, p. 25). Refugee Studies scholars trace the ways asymmetries of power and disempowerment concern how these “questions” arise and remain. Historian Peter Gatrell inquires “how the modern refugee came to be construed as a ‘problem’ amenable to a ‘solution’” (

Gatrell 2013, p. 5) through institutions such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, established in 1950, and events such as World Refugee Year of 1959. Americans contributed craft aid grounded in economic assistance and technical support to the problem–solution framework he examined. Another dimension of this framework involved signifying a problem to deflect attention from other issues. Maalki observes:

how often the abundant literature claiming refugees as its object of study locates ‘the problem’ not in the political conditions or processes that produce massive territorial displacements of people, but, rather, within the bodies and minds (and even souls) of people categorized as refugees.

Malkki’s point illuminates Americans concealing and transposing problems to the subjects of the nation dividing along the 17th Parallel. Wexler’s ideas about the “domestic image” resonate in American reliance on the domestic sphere through which to identify, bring into view, and resolve this problem, as represented by Wright and his colleagues guiding designers and developing markets at home.

The photograph of the basketmaker deflects attention from these “conditions or processes” by training the magazine reader’s focus on a subject who in reality is located far away. It brings to mind what Deborah Poole notes about the work of photographs in Margaret Mead’s and Rhoda Metraux’s

The Study of Culture at a Distance, 1953. Photographs are “privileged sites for communicating a feeling of cultural immersion, a sort of substitute for the personal experience of fieldwork” (

Poole 2005, p. 169) or an experience of being in the field, to which Wright’s image on the page opposite the basketmaker testifies. As the United States shifted from highlighting U.S. armed forces helping Vietnamese northerners migrate, to claiming they needed and deserved support in resettling, Wright delivered his view of this artisan refugee not simply as a problem, but also as its resolution post-migration.

For RWA and the State Department, the “refugee problem” was twofold: to alleviate the refugees’ dire circumstances and to leverage their potential to benefit Americans who were in a position to support craft export and consumption. RWA cemented South Vietnam’s need for aid not by elaborating on U.S. resources or by showing what refugee agencies could achieve. Instead, they linked refugees with a “road to the future” provided by the U.S. and the “Passage to Freedom” (

Department of State Bulletin 1955, p. 224). These references linked the progress, destination, and future of former northerners to a momentum fueled by the United States.

Inherently, the “refugee problem” (

Wright 1956, p. 96) established the political necessity for American aid. For the State Department, refugee resettlement amounted to a resolution of where and to what the refugees belonged. For them the refugees held several potentials for “destabilizing” South Vietnam. In “Belonging and Globalization”, Ken Lum explains that refugees are “an ‘unfixing’ figure” operating “at the thresholds of space and politics, language and power. They negotiate and produce new concepts of transcultural identities, both personal and collective that are destabilizing to established orders, systems and codifications” (

Lum 2008, p. 149). Refugees in South Vietnam had connections to ongoing civil war, they came from the north and likely they had a family there, hence they could repatriate to join communist forces or spread communism in the south. The

New York Times said South Vietnam was unstable because a “network of Vietminh agents” wanted to influence refugees and peasants there to accept the communist regime in the north (

Durdin 1955, p. E4). A major way to demonstrate the solution was to show how refugees belonged to their new nation and on trade pathways with the United States while eliding alternatives to the authority and agency Americans promoted in publicizing this scenario.

5. Occupation: From Refugees to Citizens

Consequently, towards resolving the “refugee problem”, U.S. media described refugees farming and building homes, churches, schools, and markets (

Samuels 1955, pp. 870–74). These activities would establish the refugees’ new lives in the Free World. U.S. media also promoted the self-sufficiency of refugees that had inspired them to resist communism, especially after having resettled “on the land fighting for their own rice”, as the

New York Times stated (

New York Times 1955, p. 2). Nevertheless, the State Department and the South Vietnamese government deliberated on how to settle refugees economically. The State Department hoped refugees would be able to “continue their old occupations.” Yet, it acknowledged that “many will have to be trained for other gainful employment” to “complement the economies of their new settlements” (

Department of State Bulletin 1955, p. 227). To these efforts, the Embassy of South Vietnam stated that U.S. aid was organizing the refugee population by skill and trade, with craft among the vocations (

News from Vietnam 1956, p. 4). As aid efforts homed in on “settling” refugees, RWA reported that they were willing to provide design services to facilitate native craft production in South Vietnam on a contract basis.

Before they embarked on their initial survey trip, Leland Barrows, Director of the United States Operations Mission in Saigon, wrote to Washington D.C. identifying native craft as a “tangible stake in [the] resistance to communism”. However, Barrows intensified the notion of “refugee problem”:

Need for this type help urgent. Handicraft and small industry activity suffered during war and movement of refugees to free Vietnam, many of whom were small producers, increasing the problem. Political impact resided in giving that portion of population tangible stake in resistance to communism.

In the same memo, Barrows implied that American know-how was crucial: “Believe Vietnamese to be clever and skillful but lacking in knowledge and appreciation of what it takes to make a ‘finished’ article. Artistic style not highly developed.” In reflecting on the “problem”, Barrows revealed an impulse to evaluate native craft production from the perspective of American expectations and criteria, which pervaded the American aid project. To this point, Wright echoed Barrows in questioning the refugees’ ability to make craft for export. Regarding his trip to Vietnam, he observed that craft did not seem ready to sell locally or abroad; he was concerned about the artisans’ skills. He also reported on being told that giving employment to refugees mattered because of the political situation and he wondered about the types of organization that would facilitate craft production such as cooperatives or factories (“Vietnamese Refugee Settlements”).

Wright’s contracts with the State Department called for the products made by host countries to be exported and American consumer products to be imported (“Vietnamese Refugee Settlements”). Optimistically, Wright claimed in

Interiors that, “Vietnam, where I expected to find little or nothing to export…is bursting with opportunities for the American importer or developer who goes there with designs and merchandising know-how” (

Wright 1956, p. 100). Professing to be skeptical of direct government links and control, Wright contacted leading American department stores to inquire whether they would promote craft. The majority affirmed, which prompted Wright to contact importers about bringing examples to the U.S.

Huet’s photograph of the refugee basketmaker provided an invitation to members of American interior design, home furnishings and applied and decorative arts fields to participate in importing and merchandising Vietnamese craft at home. American design industries and related businesses were crucial because they would bring the craft to the American middle class whose purchases would offset the lack of a middle-class market for craft in Vietnam. Yet, Wright had to assure these Americans in the chain of production and consumption of Vietnamese craft that artisans would not take up arms and join the communists. Rather, they would remain in the South, where Americans could rely upon them to dedicate their skills to making craft to fill orders for export.

Interestingly, the photograph pre-figured a report which the United States Operations Mission addressed to South Vietnamese President Diem in 1956. The artisan’s pathos echoes in the report’s account of the “tragic figure in your country’s first period of independence [...] the refugee, symbol of your nation’s defiance of communism.” Then, the report addresses refugee homelessness and lack of employment: “The step which is now absorbing our attention is to supply these new citizens with a means of livelihood.” This step recast the refugees’ identity. As “new citizens”, the report continues, refugees would make craft and contribute economically, helping to stave the spread of communism in Southeast Asia. The report clarified that, “In this operation, all aspects of the problem were studied carefully with the intent to fit the new citizens into the new state” (

USOM 1956, n.p.). However,

Interiors cast the basketmaker as less than a “new citizen” of South Vietnam, but rather a potential worker awaiting American entrepreneurs to help him capitalize on his artisanry. To shore up this possibility, Huet’s photograph affixed the refugee to the U.S. Protestant work ethic. It signified that the refugee works hard, therefore he is good, and he merits attention. In addition to documenting him making a basket, the photograph illustrates his productivity by including finished baskets piled next to him. In this way, the photograph transposes him from being an unknown political liability into a maker whose skills and demeanor advertise value for the American merchandisers that would relay foreign craft to American consumers.

Huet’s other photographs put forth artisans as “opportunities” (

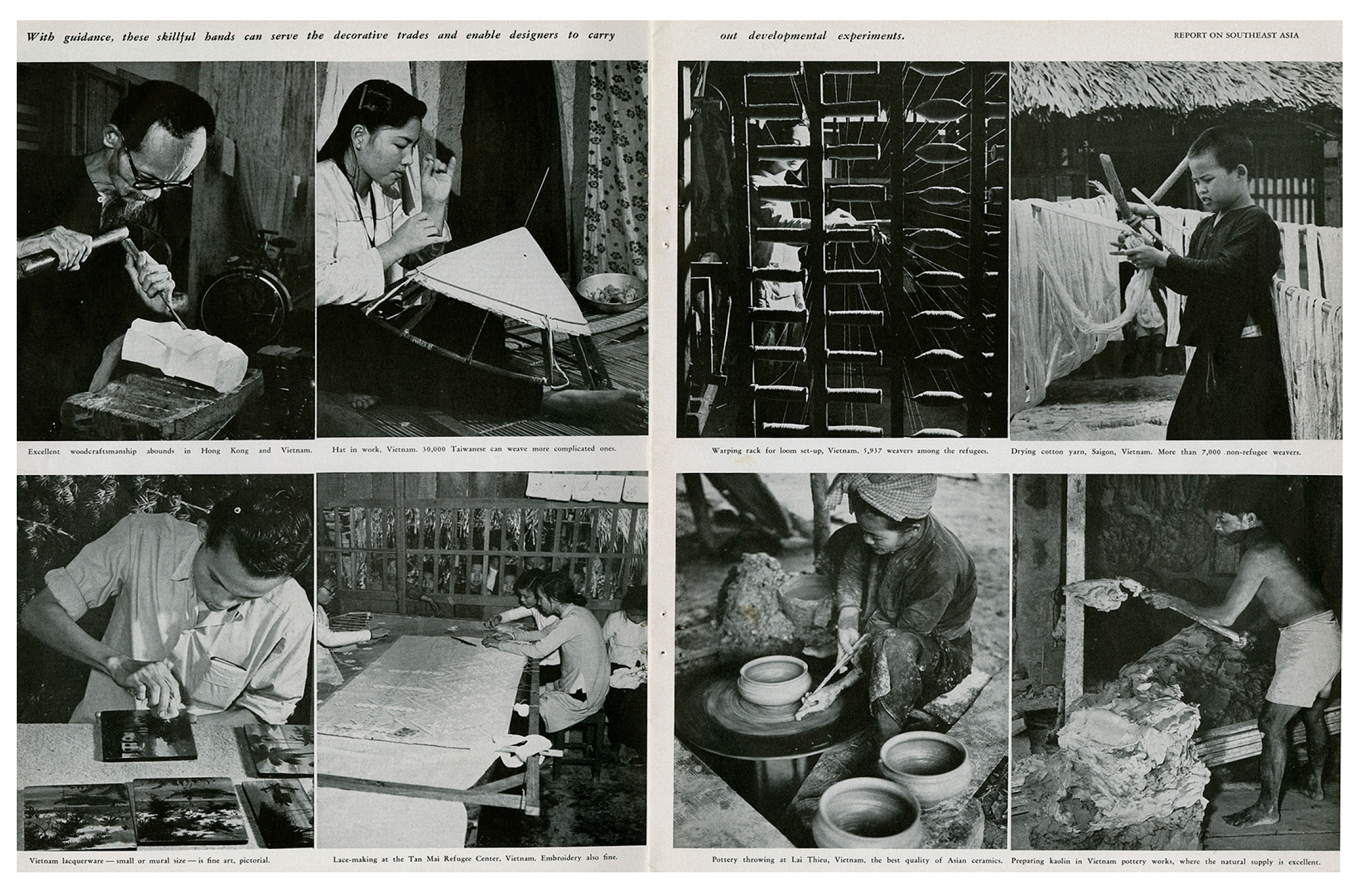

Figure 5).

These images championed artisans by featuring their focus in turning natural materials into a wooden carved sculpture, conical hats, textiles, lacquer panels, embroidery, and ceramic pottery. A caption extending across these pages explains that, “With guidance, these skillful hands can serve the decorative trades and enable designers to carry out developmental experiments” (

Wright 1956, pp. 98–99). The man carving (

Figure 2) takes his place among the others working alone or in small groups. Representing refugees as working artisans alerts us to the politics of belonging as a theme present in the American craft aid program. Belonging, Nira Yuval-Davis asserts, “becomes articulated, formally structured and politicized only when it is threatened in some way” (

Yuval-Davis 2012, p. 10). As the State Department worried about the political status of South Vietnam and Southeast Asia in the Free World,

Interiors articulated the grounds and ways that the refugees belonged within a production and consumption loop driven by American government, commerce, and the middle class, thus signifying a “peace that keeps the peace” (

Wexler 2000, p. 33).

6. Depoliticizing Artisans

A tiny, blurry photograph appeared in the middle of the

Interiors article showing Wright and his colleague Ramy Alexander standing above young men working on the ground (

Figure 6).

The men’s Western business clothes in comparison to the artisans’ “jungle” attire of naked torsos and bare legs mark sartorial distinctions. These connote the men’s authority and hint at their agency to judge the artisans, standing as they do to observe the young men who sit beneath them, working and being observed. Differences in appearance and activity situate RWA’s forays into Vietnam in a familiar albeit broader context of Western travel and discovery in the East. They resonate the trope of Western male authority traveling to the interior of non-western places to study natives in their natural habitat with the intention of capitalizing on their findings.

Nochlin wrote about tropes of Orientalism concerning the French presence in the Near East during the nineteenth century. At the time, French artists conveyed power in picturesque painting representing the Near East for “the controlling gaze” of the Westerner who “brings the Oriental world into being” and for whom that world is constituted in ways that naturalized its existence by erasing signs of its construction and change; in part, to convey “white men’s superiority, hence justifiable control over, inferior, darker races” (

Nochlin 1989, p. 45). The picturesque style in painting intertwined with Orientalism “to certify that the people encapsulated by it, defined by its presence, are irredeemably different from, more backward than, and culturally inferior to, those who construct and consume the picturesque product. They are irrevocably ‘Other’” (

Nochlin 1989, p. 51). According to Nochlin, the realist yet picturesque style of nineteenth century French academic painter Jean-Leon Gerome brought into reality his nation’s Orientalist conjurings of Near Eastern subjects (

Nochlin 1989, pp. 44, 48). Correspondingly, for Wright, Huet’s photograph of the basketmaker aspires to document culture that was vulnerable to disappearing due to civil war and, in South Vietnam, the new government’s interests in industrialization. It provides both a record and an invitation to those with the ability to act on a need for salvaging craft while helping to build a new, non-communist nation in Southeast Asia.

Wright and other Americans appreciated Vietnamese craft as pre-technological and emblematic of traditional cultures of Southeast Asia. They wanted to import craft artifacts that had “the character and personality of the particular foreign country from which they come” (

Slide lecture 1960). In their mid-twentieth century “hankering for the hand crafts” (

Schaefer 1958, p. 266), pre-industrial age features of Vietnamese craft, correlated with what Americans wanted to remind them of: everyday life objects that were made before their own industrialization. Herman characterized this impulse as “turning the clock back” to preserve Asian cottage and small industries (

Herman 1956, p. 359).

In serving as publicity for the craft programme, the Interiors article iterated the coupling of empowerment and whiteness in distinction from ethnic others. Without explicitly engaging the national discussion about identity and civil rights that was intensifying in the United States at the time, tacit differences of ethnicity and class helped to shore up the power of the whiteness of American foreign relations and its representation in the United States. These efforts may explain why the Interiors’ article is silent about Huet, the photographer of most of its images.

Huet, who was born in Da Lat Vietnam, to a Vietnamese mother and French father, went to France prior to the Second World War (

Pyle and Faas 2003, pp. 50–51). There, he studied painting at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Rennes. When drafted in 1949, Huet earned a certificate in aerial photography and volunteered for Indochina duty. He flew aerial reconnaissance, ran the photo lab, and accompanied troops (

Pyle and Faas 2003, p. 53). After being discharged from the military, he remained in Vietnam where he worked at a photo studio in Saigon and then, by 1954 if not earlier, he was working for the United States Operations Mission (

Faas and Gedouin 2006, p. 12). To highlight Huet’s mixed national heritage would have given rise to questions concerning European–Asian hybridity and issues relating to French colonialism and Vietnamese post-colonialism and brought them into dialogue with the whiteness of mainstream American culture. This could have problematized the power structure underpinning the article’s invitation to American designers to participate in craft merchandising based on a clear separation of Western whiteness from Southeast Asian non-whiteness, or otherness. After all, along with providing publicity, the purpose of the article was to invite American professionals in the design and home furnishing industries to invest in helping refugee artisans whom the article constituted as subjects of American diplomacy in their ‘pathos’ and need. “Gold Mine in Southeast Asia” treats the new arrivals in South Vietnam not as “new citizens”, rather, as resources held forth for Americans to use. “There are between 500,000 and 800,000 refugees in Vietnam eager to work but with little to do” a caption asserts (

Wright 1956, p. 100). Mining and refining this human resource would be the task for some of the readers of the

Interiors magazine.

The title page features a small photograph of Wright filming in the Lac An basketmakers’ village, which the Commissariat General for Refugees reported as having a population of over 16,000 during the first half of 1955 (

Commissariat General for Refugees 1955). Curiously, Wright appears to look across the page at the basketmaker while filming him. In a similar vein to what Deborah Poole observes is the native constituted “as object through a perceptual act”, which “both emanated from and, in so doing, constituted the ethnographer as a reasoned, thinking subject” (

Poole 2005, p. 160), in this case, the government-contracted designer. The interplay of these photographs captured a topical American perspective by rendering “geographically opaque regions geopolitically comprehensible, making them visible” to Americans as “the visualizations of [their] liberal interventions enacted in foreign lands” (

Kennedy 2008, pp. 279, 280). The direction of Wright’s gaze makes the basketmaker visible as an American “intervention” into Southeast Asia several years prior to what Americans call the Vietnam War. As Olin explains, “The gaze colors relations between the majority and minorities between the first world and the third world, whose inhabitants can be the object of the gaze because they are viewed as exotic and as living in a timeless presentness outside history” (

Olin 2003, p. 326).