1. Introduction

‘And there, quite suddenly, I slipped a gear.’

(Maitland)

It began with a shortcut to work across a car park behind Liverpool’s Adelphi hotel.

This is a walk I do almost every day, from Lime Street Station and up Mount Pleasant to my office, winding my way across the gravelly, beach-like car park that washes up on Hawke Street. And almost every day, I find myself looking forward to crossing this stretch of grey, dusty shingle. As I allow myself to be distracted, or sometimes even dazzled, by the debris strewn between the cars, I start to daydream about being at the seaside. The sound of the seagulls and the stones’ texture underfoot remind me of other less urban beaches. I look down, and the coarse, aggregate surface seems to light up with my dream-like drift of associations. It becomes a terrain studded with constellations of things that remind me of other things … a jelly-fish … luminescent coral … a sardine … sea anemone … a squid … seaweed … a fossil. And so, I start to reimagine this neglected interstitial zone as a site of psychic and material transformations: my litter-borne reverie connects one space with another space. Urban waste matter becomes entangled with far away plastic oceans. Car park becomes beach.

As I meander (or mope) my way to work, I adopt the eyes-down vigilance and posture of a gleaner or a beachcomber. I scan not for shells and fossils, but for a different order of species of flotsam and jetsam: things dropped from pockets and car-doors or just deposited by the wind that whips around the neighbouring buildings. Sometimes, I take out my phone and photograph things that I see, and sometimes I actually pick things up and put them in my pocket (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In each instance—as I gather up either an image or the object itself—it feels like an act of creative hesitation. I am waylaid by waste: I pause, stoop down, and stare intently at pieces of litter, things embedded in the ground. Then, eventually, I head off again, loop back on myself, and edge my way between the cars rather than following the more direct path, abandoning the supposedly ‘time-saving’ orientation of a rat-run. The terrain itself is so familiar that I do not particularly feel the need to watch out for obstacles, and most of the time, I do not look up.

‘Inconceivable analogies and connections are the order of the day…’

(Benjamin)

What happens, as we go about our everyday routines, when we allow our attention to be held by the discarded ‘stuff’ that we normally step over—when we find ourselves ‘looking garbage and decay in the face’ (

Boscagli 2014, p. 253)? In this article, I explore the kinds of imaginary spaces that are opened up by waste matter. Car Park Beach is one such space, my own particular version of spatial bricolage. It allows me to combine the activities of gleaning, beachcombing, and daydreaming, drawing attention to their shared concern with drift-like or tidal movements, when we move like daydreamers, we follow a drift of thought. And when we move like gleaners, we follow a drift of matter. We are ‘carried to and fro; raised, lowered; seized, lost, seized again according to the hour and the day’ (

Valéry 1950, p. 168).

On Car Park Beach, I look for connections between different spaces, different objects, different communities, and different moments in time. And perhaps most crucially, I chart the trajectories of what Walter Benjamin might call ‘inconceivable analogies’ (

Benjamin [1978] 2007, p. 183). Tracing the syntactical patterns of the daydream, I return again and again to one persistent, potentially baffling, association: my ‘inconceivable analogy’ between car park and beach.

In his 1929 essay ‘Surrealism: The Latest Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia’, Benjamin writes about a city in which both subjectivities and perceptions are frayed, where ‘dream loosens individuality like a bad tooth’ and ‘crossroads where ghostly signals flash from the traffic, and inconceivable analogies and connections between events are the order of the day’ (

Benjamin [1978] 2007, p. 183) (see also

Gordon 2008, p. 204). Rather like a doubly exposed photograph, Benjamin’s city is pictured as a layered and over-determined sensorial realm. This image of urban space as an assemblage of intersecting, residual, and parallactic structures is key to my own practice. In this article, I hope to conjure up the same sense of ‘double-exposure’—or multiple exposure—to reveal what might happen when spatiality and temporality are imbricated and waste matter itself comes to be associated with shifts in consciousness (see

Figure 4).

‘The heart, the fluttering of the eyelids, the movement of a street, or the tempo of a waltz’

(Lefebvre)

My walk across Car Park Beach is familiar and predictable, yet also shaped by the rhythms of daydreaming and distraction (cf.

Lefebvre 2004;

Edensor 2005). So, as I repeat these manoeuvres (getting later and later for work each time), my shortcut takes on certain ritualistic qualities—forming itself into a paradoxically routine dérive (or—equally oxymoronically—a fûgeur’s commute). Maybe I can make sense of this seeming contradiction of

wandering or

drifting around a ‘predictable circuit’ by thinking of it as a

refrain? For Deleuze and Guattari, the refrain—exemplified by birdsong—is ‘a territorial assemblage’ and ‘always carries earth with it.’ (

Deleuze and Guattari [1987] 2013, p. 363). Or put another way, the refrain ‘marks territory’ by drawing together action and sensation with the ‘stuff’ of environment.

In her afterword to

The Affect Reader, Kathleen Stewart takes up Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the refrain. She emphasises the ways that our lives are made up of a ‘hodge-podge’ of physical and social encounters—heterogeneous assemblages, which intertwine mobility with matter, sensation with stuff. According to Stewart, our accumulated ‘rhythms of the present’ are capable of generating a

more connected world, whereby ‘a condition, a pacing, a scene of absorption, a dream,’ leads to ‘the dense entanglement of affect, attention, the senses, and matter.’ (Stewart in

Gregg and Seigworth 2010, p. 340). As if to emphasise this tendency for action and material to coalesce, Stewart’s own prose often seems to be shaped by a syntax of over-scoring and accumulation. For example, her sentence fragments take on the looping qualities of a record stuck in a groove when she writes about ‘a scoring over of a world’s repetitions. A scratching on the surface of rhythms, sensory habits, gathering habits, gathering materialities, intervals and durations. A gangly accrual of slow and sudden accretions. A rutting by scoring over’ (

Gregg and Seigworth 2010, p. 339). Perhaps, then, like Stewart, I am beginning to ‘etch’ an ‘almost occult’ ‘worlding refrain’ (

Gregg and Seigworth 2010, p. 339)? Perhaps a spectral patina of crossings and re-crossings is forming behind the Adelphi Hotel, thoughts of things accumulating between the cars.

2. ‘The Ghosts of Plastic Perform an Enigmatic Choreography’ (Chaudhuri)

Car Park Beach is full of ghosts. Phantoms appear in the form of plastic bags or pareidolic milkshake lids (

Lee 2016), and there are even streaks of Clingfilm ectoplasm sticking to the shingle (see

Figure 5). There is also something a little ghostly about the swash and backwash of my repetitive commutes. Perhaps my ‘desire lines’ are leaving vapour trails, my movements dissolving back into the surface of the car park. According to Tim Edensor, ‘mundane haunting’ is constituted through ‘the rhythms of domesticity’ and ‘regular practices … sedimented in neighbourhoods’ (

Edensor 2008, p. 326). I have a feeling that my actions too are leaving sediments. I am re-tracing my steps along previous strandlines.

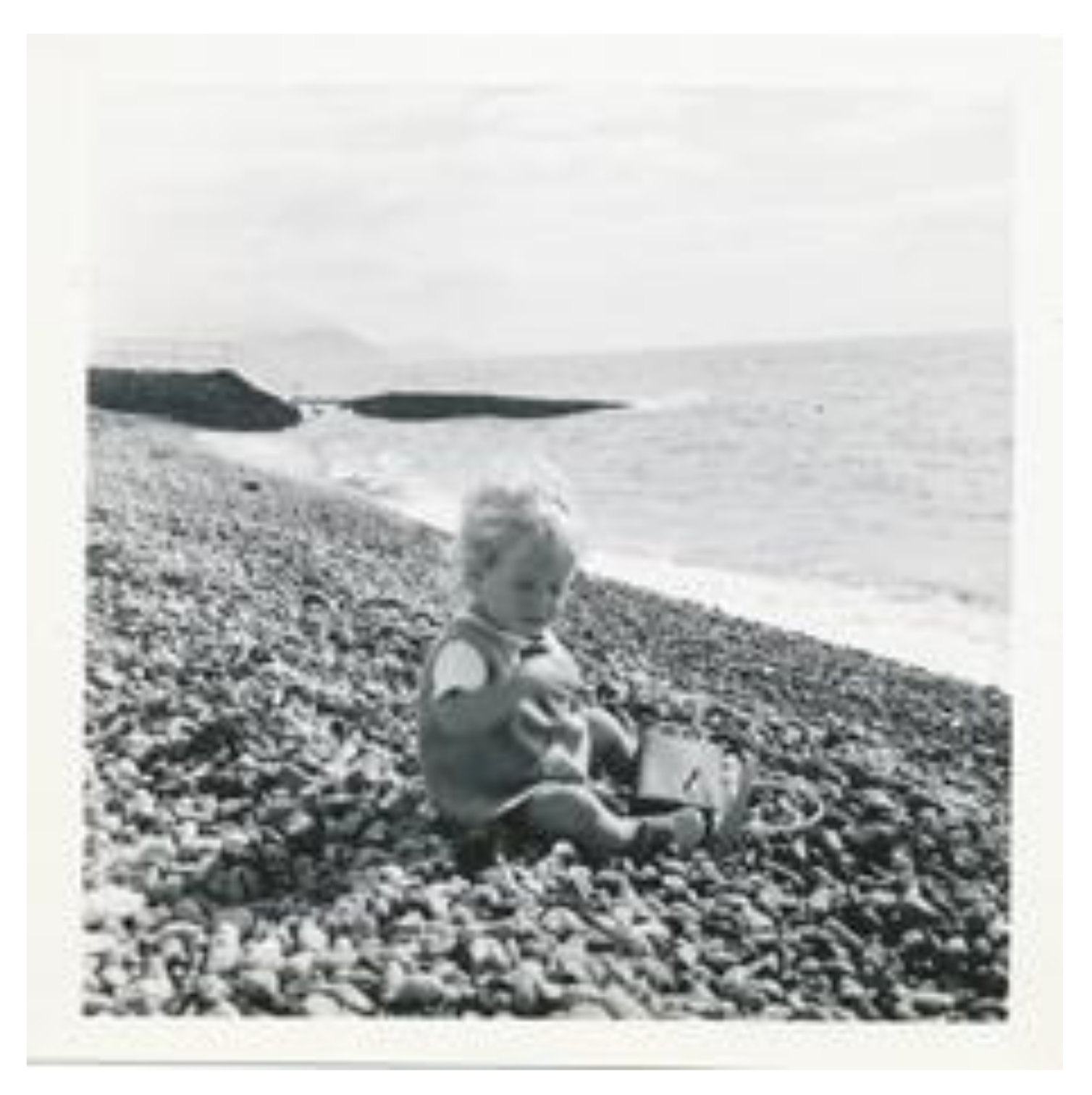

As I fix my gaze downwards, leaning in for a closer look at something shiny that catches my eye, I am repeating the nostalgic choreography of my previous incarnations as a beachcomber. I’m excavating, or maybe exorcising, kinaesthetic palimpsests of other beaches I have known—Brighton, Lyme Regis, Arisaig, Hoylake, and St. Helen’s on the Isle of Wight. In a way, the Adelphi Car Park is just another beach to add to my collection, another entry on my roll call of beaches (cf.

Andrews and Roberts 2012). But these littoral revenants that I summon up as I glean seem to speak as much to me about the future as the past (cf.

Viney 2015). Like Brian Thill, ‘I cannot seem to see objects embedded in their present time’. Instead, ‘they always carom off the edges of the present and into the past and the future’ (

Thill 2015, p. 7). My gestures, the photos that I take, and the things that I stash in my pockets, feel less like souvenirs than portents.

‘A shore whose message is not the message in the bottle, but is the discarded bottle itself’

(Thill)

According to Serenella Iovino, waste can offer an imaginative conduit to that which is otherwise culturally disavowed: ‘[It] is the other side of our presence in the world, our absence made visible,’ (

Iovino 2009, p. 6—cited in

Alaimo 2016, p. 138). The idea of waste as a ‘visible absence’ sounds like a version of borderline representation (

Green [1972] 1996)—not unlike a ghost perhaps, but a ghost whose return is guaranteed. And plastic, of course, is probably the most persistent spectre of all, always shadowed by the promise of material resurrection. For Timothy Morton, it is this capacity to persist, to ‘stick’, which transforms objects such as ‘Styrofoam or plastic bags’ into

hyperobjects (

Morton 2013, p. 1). Or, as Pippa Marland puts it, plastic hyperobjects have an ‘“inverse” ghostliness’—they are ‘our uncanny agential kin, both

of us and different from us in their potentialities’ (

Marland 2015, p. 124).

‘Is it possible’, Marland asks, ‘to explore how we

feel about the “matter” of plastic waste?’ (

Marland 2015, p. 123). Through a reading of Kathleen Jamie’s

Findings, Marland attempts to answer this question by foregrounding the ‘dissonant kinship’ evinced by the plastic flotsam that Jamie finds on a visit to a Hebridean beach. For example, a beachcombed ‘severed plastic doll’s head’ (

Marland 2015, p. 129) seems, for both Jamie and Marland, to articulate the capacity for plastic waste to ‘persist, relatively unchanged’ (

Marland 2015, p. 130). And it is precisely this quality of less embodied, uncanny persistence, which at first seems to lessen the plastic doll’s head’s value as a beachcombed object. Jamie decides to leave it behind on the beach, yet later regrets her decision and begins to dream of using it as a paperweight. Like Morton’s hyperobject, the plastic doll ‘sticks’ with her and prompts a strange sort of kinship, one which—for all its dissonance—proffers Jamie a connection to the landscape. The absent presence of this ‘strange stranger’ (

Marland 2015, p. 129) on her desk might allow her to ‘keep the writing earthbound’ (

Marland 2015, p. 129), but her thoughts of the plastic doll’s head also seem to trace the ‘footprints of hyperobjects’ (

Morton 2013, p. 5).

What seems to be at stake here is a flow of affect between human and plastic matter which folds the ‘outside’ back in on itself. As a signifier of uncertain, non-local boundaries, plastic opens up possibilities for porous identification: it permeates our mind and bodies. Plastic leaches into our organs, migrates across oceans, blows our minds. Again, what we seem to be dealing with is a borderline representation—a material category that troubles our sense of the division between human and non-human, inside and outside, and valued and un-valued matter. According to Morton, a time of hyperobjects offers us ‘no outside, no metalanguage’ (

Morton 2013, p. 5). Transformed by this dizzying exchange between container and contained, we become shells, like Morton, ‘scooped out from the inside’ (

Morton 2013, p. 5).

Shells…

For Gaston Bachelard, there are moments when ‘space relaxes and falls asleep’ … when ‘we dream of an object, (and) enter into that object as into a shell.’ (

Bachelard 1971, p. 172). Just as Stewart’s ‘worlding refrain’ turns upon ‘the hinge between the actual and the potential’ (Stewart in

Gregg and Seigworth 2010, p. 339), so Bachelard’s conception of ‘material reverie’ seems to form itself around an equivalent ‘hinge’ along the unravelling seams between ‘object’ and ‘dream’. And even though there is something paradoxical about any form of dream that has a

material presence, my own ‘material reverie’ on Car Park Beach attempts to follow this same impulse to fuse material and psychic states, to explore ‘the immediate synthesis of things and ourselves’ (

Bachelard 1971, p. 173).

It is no coincidence that Bachelard uses the image of a shell to convey this sensation of merging ourselves with our material environment (

Bachelard [1964] 1994, p. 108). A shell, after all, is both embodied shelter (exoskeleton, armature) and aestheticized waste object. And, as a trope of subjectivity, a shell connotes spiralling interiority, a retreat back into matter (cf.

Abraham and Torok 1994). For Bachelard, the shell explicitly represents in-betweenness—a borderline space, which contains a borderline subject: ‘[A] creature that comes out of a shell is not only “half fish, half flesh,” but also half dead, half alive, and, in extreme cases, half stone, half man’ (

Bachelard [1964] 1994, p. 109).

For Stacey Alaimo, shells are also associated with in-betweenness. In her book

Exposed, she uses the figure of ‘your shell on acid’ (

Alaimo 2016, p. 143) to articulate a very different kind of borderline existence—an ‘ecodelic’ state of ‘dwelling in the dissolve’. Alaimo writes about billions of pteropods whose shells are dissolving in our increasingly acidifying seas. She points out that the uncanny, fragile beauty conjured by the shell’s evanescence ‘lures us into a pleasurable encounter which nonetheless gestures toward the apocalyptic’ (

Alaimo 2016, p. 164). Crucially, though, she also argues that ‘these shells bereft of their fleshy creatures, without a face, nonetheless evoke concern, connection, empathy’ (

Alaimo 2016, p. 164). Even now, shells still provide conduits to distant oceans.

Shells are the beachcomber’s currency, par excellence. We fill our pockets with them at the seaside, and we carry them home. Lined up on the mantlepiece or immersed in jars full of bleachy water, shells attest to our desire to sustain a connection with the sea. Whether we hold them to our ears so that we can hear the waves or we watch the ‘slow violence’ of their dissolution on our TV screens, shells remind us that our relationship to the world is porous. These days, I have been filling my pockets with a new collection of precious waste matter, but now my conduits to distant oceans are made of plastic.

3. The Street Beneath the Beach?

Not far away from Car Park Beach—just up the coast at Ainsdale Sands—the poet Jean Sprackland spent a year beachcombing on a single stretch of shore. In her 2012 book,

Strands: A Year of Discoveries on the Beach, Sprackland recounts her ‘complex and intimate’ relationship to a beach that has become ‘an inner as well as an outer landscape … the setting for dreams’. For her, ‘this stretch of coast’ is ‘all about change, shift, ambiguity’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. xi), and as she meditates upon its temporal and spatial mutability, her familiar shorescape is pictured as ‘a shapeshifting place, in league with the wind’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 4). Here, both the tide and the sand itself are agents of transformation. And as the environment moves and reconfigures itself, so the relationships between conscious and unconscious, and natural and unnatural seem to become more porous, more reversible. Or perhaps—to use Merleau-Ponty’s term—these relationships are ‘chiasmic’, caught up in a ‘reciprocal insertion and intertwining of one in the other’ (

Merleau-Ponty 1968, p. 138).

Early in the book, Sprackland describes an ‘exceptional’ day when ‘the landscape is transfigured’, revealing three ship wrecks (

Sprackland 2012, p. 4). This encounter seems to take on epiphanic resonances for her, conjuring a vivid recollection of ‘the magic of hidden realities beneath the surface of things’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 5) that she had sensed as a child. At the sight of these ‘three broken old ships’, she is transported back to an early experience of peering down through a ‘grille on the pavement’ and imagining that she can see a ‘secret bunker … full of broken dolls’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 5). Such a striking image of uncanny, perhaps even abject, waste skews what otherwise might be a fairly traditional representation of the seascape as sublime. In other words, Sprackland presents us with a scenario that subverts the romantic convention of seeking profound insight through contemplation of a

vast natural space. Instead, she seems to ‘negotiate rapture’ by drawing attention to

stuff. Whether it takes the form of shipwrecks, broken dolls, or chocolate wrappers, waste matter opens up imaginative spaces. It provokes ‘sublime seizure, a caesura in everyday life’ (

Bhabha 1996, p. 8) (see also

Maitland 2009). Thus, the recollected feelings that Sprackland associates with looking down a drain seem to touch upon a state of enchantment: ‘… the scene on the beach today reminds me of the vital feeling I experienced as I knelt on the tarmac with my six-year-old cheek pressed to the cold metal:

There is more to things.’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 5).

As Sprackland’s thoughts move away from the beach and back to the childhood ‘thrill’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 5) of enchanted urban waste, there is an unlikely reversal of my own imaginative leap from car park to beach: instead of revealing ‘the beach beneath the streets’

(‘sous les pavés, la plage’), Sprackland daydreams of the street beneath her beach (

sous la plage, les pavés).

‘It brings them back, and takes them away, and brings them back again’

(Sprackland)

Strands is far from being an unproblematic celebration of the ‘natural’ beach. Sprackland laments that it is no longer possible to ‘walk along a seafront in a storm without thinking of climate change’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 213). Each discovery she makes along the tideline seems to resonate as both ‘elegy and omen’. For Sprackland, ‘our very ways of thinking, speaking, reading and watching’ are irrevocably altered by the prospect of ‘ecological meltdown’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 213), and even the tide—her central narrative motif—fails to function as a metaphor for cyclical renewal. Standing on Ainsdale Sands, with a Marathon wrapper in her hand, she reminds us that ‘we can obey the instructions to dispose of it thoughtfully, but we can’t make it disappear, however often we chuck it away’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 105).

This account of plastic flotsam and jetsam draws attention to the reversibility of Iovino’s trope of ‘visible absence’, not least because Sprackland’s ‘sobering moment’ of ecological revelation is triggered after an unusually high spring tide by the sight of ‘the beach (washed) clean and shining’. She describes ‘a glorious day in March’ when she finds that ‘the mass of accumulated debris I’d seen there the week before was gone. The sea had swallowed it again.’ (

Sprackland 2012, pp. 117–18). When the tide performs its apparently magical vanishing trick, what should be a narrative of nature’s capacity to renew itself is read by Sprackland as a different kind of story altogether. In other words, it is the very evanescence of waste—its

absent visibility—that haunts her: ‘I understood then that for the bottle and the laundry basket, the clothes peg and the doll, the petrol can and the chocolate wrapper, this is a story with no end’ (

Sprackland 2012, pp. 117–18) (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

‘Oh! I do like to be beside the seaside!’

(Banksy)

Sprackland refers briefly to a book by

Hugh Stoker (

1956)

The Arrow Seaside Companion—mentioned only perhaps, to calibrate her present sense of an ‘agonisingly painful loss of innocence’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 117). Of course, even the word ‘seaside’ has a nostalgic ring to it, and Sprackland describes how Stoker’s ‘straightforwardly wholesome’ and ‘jolly’ 1950s world seems untroubled by worries about ‘sewage waste, radioactive contamination or sinister sex changes in limpets’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 117).

Published just 16 years after Stoker’s

Seaside Companion, Tony Soper’s

The Shell Book of Beachcombing (1972) seems poised on the brink of a new era of environmental unease. With the corporate colours of its red and yellow banner and its conspicuous Shell logo, this book apparently hails from a time when such overt cognitive dissonance was possible—when multi-national oil companies could unapologetically lend their brand to a book about beaches written by a famous naturalist. Yet, reading

The Shell Book of Beachcombing today, one is struck by its failure to sustain Stoker’s pre-lapsarian vision of a more innocent littoral past. There are strains of both ‘elegy and omen’ (cf.

Sprackland 2012, p. 213) in Soper’s narrative—and perhaps most portentously—plastic is beginning to make its presence felt on the strandline, alongside the cuttlefish and driftwood.

On the one hand, Soper seems to take the changing constituency of flotsam and jetsam in his stride. He insists that beachcombers must ‘adapt to the change and learn to enjoy the plastic artefacts which decorate the tideline’ (

Soper 1972, p. 76). On the other hand, he mourns ‘the swing towards a plastic float’ (

Soper 1972, p. 84) and reminisces about a previous era when ‘one of the pleasures of early morning wrecking used to be the colourful glistening of a glass float in the wet sand and the low sun’ (

Soper 1972, p. 87).

Whether he is describing ‘dangerous little balls’ of nylon fishing line (

Soper 1972, p. 83) or the innovative use of ‘plastic seaweed’ to combat coastal erosion (

Soper 1972, p. 77), Soper seems, by turns, to regret and to celebrate the arrival of plastic. But in 1972, there is apparently still something

human scaled about the threats posed by such objects: synthetic lines are hazards because they ‘sometimes wrap themselves around boat propellers with dire consequences’; and ‘detergent bottles and flip-flop shoes’ only really pose a challenge because the foreignness of their ‘inscriptions’ could ‘stretch our command of language’. (

Soper 1972, pp. 76–77). In other words, for Soper, plastic waste has not yet entered the realm of Morton’s hyperobjects (

Morton 2013). For us, perhaps the idea of ‘plastic seaweed’ washing up on our shores smacks almost unbearably of a dystopian Anthropocene future. But for Soper, it apparently sets a comforting imaginative limit: ‘[I]t is difficult to imagine anything more exotic than plastic seaweed’ (

Soper 1972, p. 77).

In 1972, plastic may be ‘exotic’, and it may be invasive, but it is still somehow recuperable to a benign discourse of beachcombing; it can still be salvaged, both literally and metaphorically. In 2017, it is hard not to see Soper’s ‘plastic artefacts’ as harbingers of our devastated oceans, but in 1972 plastic remains graspable,

collectible, and unlike Sprackland’s ‘story with no end’, it manages to offer the prospect of a happy ending. Soper may anticipate a more plasticized world, but it is still possible for him to imagine that world as homely. Indeed, he explicitly invites us to picture plastic waste as cosily domestic when he writes that ‘sometimes [plastic artefacts] too will have bristle worms and barnacles attached to them, and jammed in the right place they may provide a home for a crab or an anemone.’ (

Soper 1972, pp. 76–77).

Sprackland and Soper are writing forty years apart, but they seem to be connected by the same beachcomber’s anthem of strung together plastic treasures. In 1972, Soper writes about ‘detergent bottles and flip-flop shoes’, and then—years later—Sprackland picks up the same refrain with her incantatory list of ‘the bottle and the laundry basket, the clothes peg and the doll, the petrol can and the chocolate wrapper’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 118). What does this inventory of beachcombed plastic waste tell us? That Soper’s bottle may also be Sprackland’s bottle. That nothing and everything has changed. (See

Figure 8).

‘When I look for the hyperobject oil, I don’t find it. Oil is just droplets, flows, rivers and slicks of oil’

(Morton)

The Shell Book of Beachcombing was published less than five years after Britain’s ‘worst ever environmental accident’, so it is hardly surprising that ‘oil and tar’ feature prominently in the chapter headed ‘horrors of the beach’. In 1967, the Torrey Canyon tanker was shipwrecked off the coast of Cornwall. It was chartered by BP (still a partner company of Shell-Mex at the time) and was carrying 120,000 tons of crude oil (

Gill et al. 1967). Hundreds of miles of beaches and wildlife were catastrophically affected, not only by massive, choking slicks of oil, but by ‘millions of gallons of toxic dispersant’ (

Soper 1972, p. 111)—predominantly a chemical produced by BP called BP 1002 (

Barnett 2017).

According to Soper, the havoc wreaked on ‘intertidal flora and fauna’ (

Soper 1972, p. 111) by dispersants was, if anything, more damaging than the oil spill itself. Again, there is a double-edged tone to Soper’s account, perhaps not least because, having published the first environmentalist critique of the Torrey Canyon disaster in 1967 (

The Wreck of The Torrey Canyon), he now finds himself writing under the corporate banner of Shell. He uses reassuring phrases such as ‘the affair has prompted research’, and ‘contingency plans are much better developed’ (

Soper 1972, p. 111). Perhaps most significantly, he suggests that the potential

scale of effects wrought by oil spills is

containable; it is rendered human through a discourse of beachcombing. After all, oil and tar are apparently just one ‘horror of the beach’ among many, scaled down by the familiar syntax of a beachcomber’s inventory. Less hazardous than broken glass, oil and tar are an inconvenience to be sidestepped alongside quicksand, biting conger eels and stinging lesser weever fish.

Reading Soper’s text now, my thoughts return to the tar splattered beaches of my own childhood on holiday in the Isle of Wight and later in Brighton. Back then, eucalyptus oil, which will ‘clean your body, your clothes or your carpets with ease’ according to Soper (

Soper 1972, p. 111), was as much a smell of the beach as ozone. For me, this is a heady yet ambivalent olfactory association, and I find it hard to resist the disorientating undertow of nostalgia when I think about oil and tar on the beach. It might be that

The Shell Book of Beachcombing exerts a particular fascination for me, because—like Soper—my own beachcombing in 1972 was shadowed by the presence of a multi-national oil company. Between 1969 and 1994, my father worked for BP’s marketing department, and throughout my childhood, our house was full of objects bearing the corporate logo: diaries, stickers, records, t-shirts, cutlery, and hats. I learned to swim at the BP sports club and built miniature homes for BP Smurfs. I coveted the Perspex BP paperweight on my father's desk, which contained a teardrop of North Sea oil (see

Figure 9).

It is strange to think that my childhood memories are branded with the same logo that Banksy deploys with such stained sentimentality in his 2010 dolphin and BP oil slick installation on Brighton pier (‘Pier Pressure’,

http://banksy.co.uk/out.asp) (

Banksy 2010). Yet, even today I connect the green and yellow BP shield with a muddled realm of affect and identification, and perhaps that is why I am so preoccupied with the mixed messages of Soper’s text. Somehow, ‘the simplicities of childhood’ (

Sprackland 2012, p. 214) have become entangled with an ecological pariah, the environmentalist’s bogeyman, and I am not quite sure what to do with this particular drift of associations. Perhaps ‘drift’ is the wrong word. Tim Morton tells us that ‘… hyperobjects are

viscous: we can’t shake them off; they are stickier than oil and heavy as grief.’ (

Morton 2013, p. 180). So, perhaps what I mean is: oil

sticks to my thoughts. It carries me from one slick to another—from the Torrey Canyon to Deep Water Horizon to the Pacific’s petrochemical gyres of oil-based plastics (

Zurkow 2014).

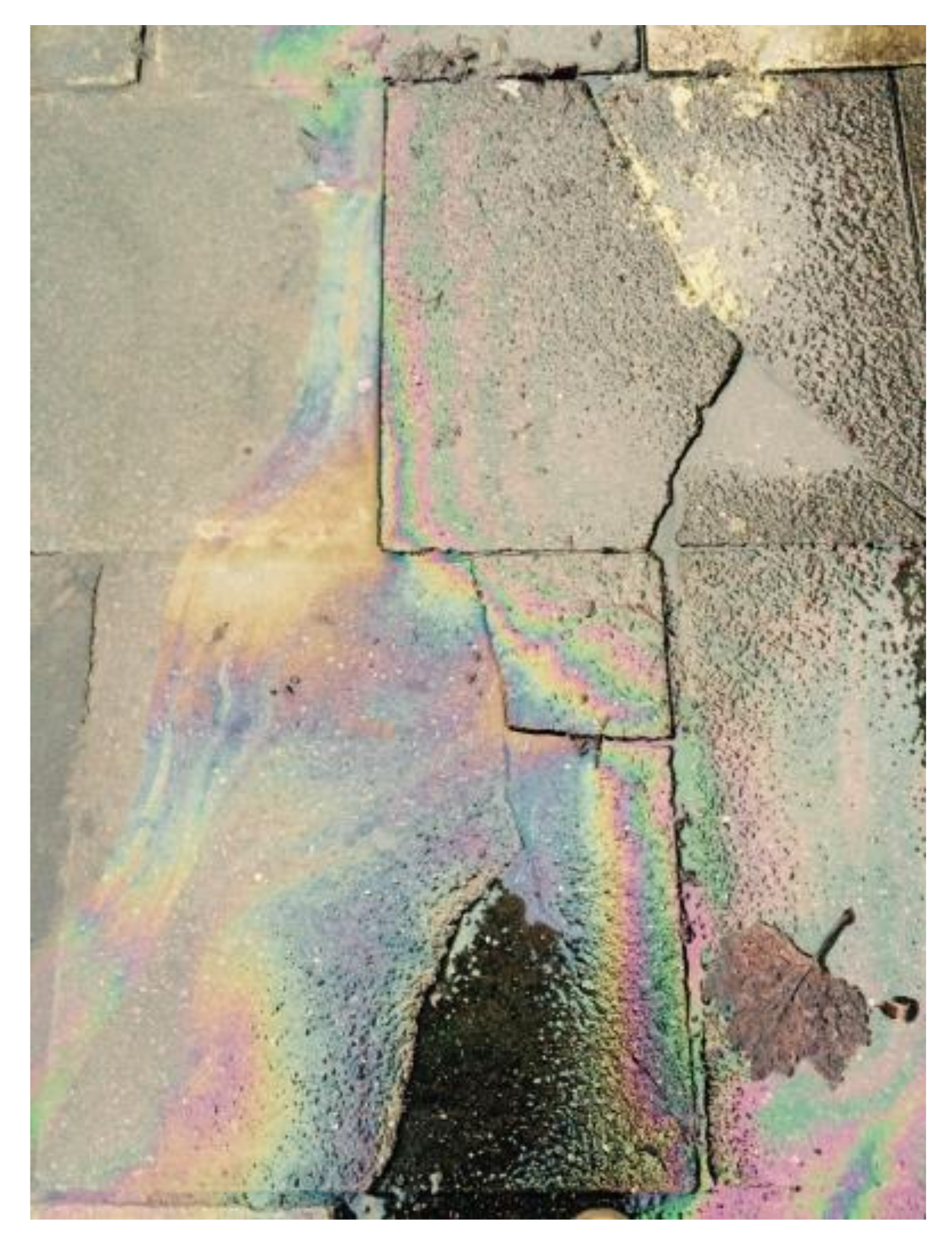

These days our beaches are more likely to be pockmarked with nurdles than tar (

Guins 2009). But on Car Park Beach the shingle still glistens with patches of oil, leaked from the underbellies of cars and coaches (see

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

4. ‘If We Opened Me up We’d Find Beaches’ (Varda)

In her 2008 film,

Les Plages D’Agnès (

2008), the filmmaker Agnès Varda uses a language of beaches to tell stories about her past life, and it is tempting to do the same here—to reimagine my own personal history as a series of ghostly beaches (see

Figure 12). But Car Park Beach is not a memoir, and

Les Plages D’Agnès is not a straightforward autobiography (cf.

Taussig 2006). Much of Varda’s recent work is shaped by techniques of both temporal and spatial bricolage. For her, bricolage is a ‘work of unbounded creation’ (

Winston et al. 2017, p. 131), and whether she takes on the mantle of beachcomber or gleaner, she celebrates a

poetics of making do, of picking over the leftovers (‘beaux-restes’). Rather than rendering disparate elements coherent, as Lévi-Strauss’s idea of the ‘bricoleur as engineer’ might suggest, (

Lévi-Strauss 1962, p. 11) Varda as bricoleur (or bricoleuse?) uses collage-like methods to create digressive, discontinuous narratives: her version of bricolage often seems to be less about

stitching or

sticking together and more about

unravelling.

Varda’s

Les Plages D’Agnès disrupts the conventional narrative rhythms associated with ‘finding ourselves’ on the beach. The film opens with Varda and her crew arranging a collection of mirrors along the shoreline. The beach’s more familiar mise-en-scène is replaced with domestic scenery; not only do these ‘out of place’ mirrors recast iconic household objects as flotsam, they also represent the refracted, composite nature of Varda’s storytelling. Her filmic version of spatial bricolage effectively fractures and deflects the flow of the shorescape and parodies the idea that beaches are places to ‘reflect’ upon who we are. Rather than seeking a vantage point that allows us to project emotion

outwards onto the sea’s vastness, Varda turns her attention downwards and backwards. She eschews the rhetoric of ‘magnetic’ oceanic horizons, and in several scenes, she directly turns her gaze

away from the waves, walking backwards along the shore. Littoral space is reconfigured as inverted and helical. (See

Figure 13).

Early on in

Les Plages D’Agnès, Varda, as narrator, proclaims that ‘if we opened me up we’d find beaches’, a gesture which seems to proffer the ‘guts’ of her experiences like a shucked oyster. As she addresses her audience with such intimacy and potential carnality, she not only conjures a narrative trajectory, which is messy and non-linear, she also

turns inside out our conventional spatial identifications with beaches. In effect, Varda’s shell-like image of interiority elides dream-like memory with something much more visceral. And the beach, like Varda herself, becomes a container that folds the outside back into itself. Somehow, I picture Varda ingesting and regurgitating one beach after another—a chain of beaches inside beaches inside beaches. This in turn reminds me of Chris Jordan’s apocalyptic photos of albatrosses with their entrails of plastic waste (

Jordan 2009). Brian Thill describes how ‘looking down into the innards of (Jordan’s) plastic-choked birds’ provokes a ‘vertiginous feeling’ (

Thill 2015, p. 12), and crucially, he compares this sensation to

gazing down into the wet brown spaces of the train tracks to see what we find there, in the dark places where fetid puddles of assorted liquids mingle with grungy water bottles, soda cans, expired Metrocards, flattened bits of mildewed paper, and other objects smudged and smashed beyond recognition.

Thill (like both Varda and Sprackland) seems to shift his gaze away from the expansive possibilities of the horizon (see also

Mentz 2015). Of course, the albatross ought to be a signifier—albeit a ruined one—for airy oceanscapes and the promise of the open sea. Here, however, ‘the plastic-choked birds’ turn us away from the shore to face inland and back to another waste-site altogether—an urban, subterranean midden. In other words, the agentic qualities of waste matter once more seem to reveal ‘the street beneath the beach’. (See

Figure 14).

5. Treading Water …

On Car Park Beach, as I hesitate again at the sight of another fossil-like bottle top, the momentum of a conventional journey from A to B is suspended. If only because of my tendency to stall, to re-trace my steps, and to look down drains, I suppose that anybody watching me might think I am someone who has ‘lost direction’, who is directed by irrational thoughts and motivations. Perhaps I am somebody who is ‘lost’ or ‘possessed’ in the sense that I have become ‘pathologically attached to waste matter’? It is not surprising that

Possessed is the title of Martin Hampton’s wonderful film about hoarders (

Possessed 2008). The so-called symptoms of hoarding are often characterised in terms of a series of open-ended present participles: ‘churning’, ‘processing’, ‘sorting’, ‘sifting’, ‘holding on’, ‘moving back and forth’, and so on (cf. DSM-5). Like a hoarder, I also find myself shaped by this grammar of the continuous present—turned against the temporal and spatial flow of linear action. You could say that I am ‘treading water’, ‘moving back and forth’ with the tide, my downward gaze ‘holding on’ to the strand.

‘Keep your eyes firmly on the strandline’

(Soper)

According to Agnès Varda, the tilting of the body and eyeline down towards the ground is what most emphatically characterises the gleaner, and in her 2000 documentary film

Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse (

Varda 2000) she celebrates the action of ‘stooping’ (‘se baiser’) as a paradoxical gesture of political and aesthetic defiance. Taking on the gleaner’s peculiarly intense concern with the movement of matter, Varda reminds us that when we stoop (

se baiser) we also almost kiss the ground (

se baisser); we connect to the material world differently—with both sensory pleasure and with political acuity … or as Benjamin puts it, ‘with tactile nearness’ (

Benjamin 1999, p. 848). Varda’s picaresque narrative about different communities of gleaners is intertwined with intimate footage of her own life. For instance, we see Varda unpack her suitcase after a trip to Japan. The poignant domesticity of this scene in Varda’s apartment, with its growing patch of damp on the ceiling, enables us to experience her gleaning aesthetic ‘up close’. The camera lingers on her hands as she touches her treasured possessions. Of course, the camera itself is ‘hand-held’ too.

Varda’s (literal) inclination to look down and to touch seems to suggest that the gleaner’s mobility is open both to the rhythms of old age and to those of childhood. According to Maurizia Boscagli, Varda’s 2000 documentary is ‘an encounter with (the film-maker’s) own “laying to waste” through aging’ (

Boscagli 2014, p. 255). Certainly, as Varda’s camera lingers over the wrinkles and liver spots on the back of her own hand (‘film[ing] with one hand my other hand’), she seems to bear witness to her own embodied stories. And her use of non-sequential shots of the expanding, then shrinking, white parting in her dyed dark hair highlight how we are moving back and forth both in space and in time. But Varda’s attention to ‘moments of chance encounter, gratuitousness and play’ (

Boscagli 2014, p. 260) means that her representation of temporality is far from monolithic. For example, Varda leans out of the car window and mimics the shape of a camera lens with her fingers. Trying to ‘capture the big trucks’ on the motorway (

Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse 2000), she deliberately invokes a child’s gestural language. Such an action suggests that Varda wants somehow to

hold onto the flow of matter through space, particularly matter that she associates with childhood memories. Yet, when the interviewer asks if she is trying to ‘retain things passing’, Varda insists that she just wants ‘to play’ (

Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse 2000).

‘They’re going to follow the receding sea, and anything they find they pick up.’

(Varda)

In both

Les Plages D'Agnes and

Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse, there is a haptic quality to Varda’s cinematography. According to Laura Marks, haptic looking ‘tends to move over the surface of its object rather than to plunge into illusionistic depth, not to distinguish form so much as to discern texture’ (

Marks 2000, p. 162). With her repeated use of rather blurred tracking shots (taken from a car window) and her bumpy close-ups of things on the ground, lens cap still dangling in view, Varda certainly emphasises the tactility of her camera’s movements and ‘privileges the material presence of the image’ (Marks cited in

Ince 2013).

This is the gleaner’s gaze, traced across different shorescapes and landscapes, from fields and motorways to the leftovers of city markets. Like a gleaner, or a beachcomber, or even a hoarder, Varda stoops to salvage waste matter on the move, picking up stuff as it disperses and mutates in our everyday landscapes. And sometimes, like a bricoleur, Varda stitches her films together from bits and pieces that might otherwise end up on the cutting room floor.

Whether in a field, an orchard, an oyster bed, a skip, a supermarket bin, or even a car park, gleaners pick things up that have been left behind—stuff that is surfeit or overlooked … the ‘beaux restes’ (leftovers) of harvest. In Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse, Varda explores the ancient rights of the gleaner in France, set down in law in the 1554 Penal Code. Much of the legislative detail offered in the film reveals a preoccupation with stipulating distances in space and time, and there is also a tacit acknowledgement that these rules are precarious. It seems that, wherever it takes place, gleaning is an ‘after-thought’, characterised by a refrain-like attention to traces and residues. ‘From sunrise to sunset when the harvest is over’, gleaners follow in the material footsteps of others. Their mobility is shaped by the ‘afterwardness’ of matter.