1. Introduction

“There is no busker ‘type’…there are all types,” FX, a vocalist-guitarist, tells me on a Sunday afternoon at Place-des-Arts station. “The busker,” he continues, “may be one of the freest musicians, in terms of musical choices.” But, the downside is that it doesn’t pay all that well. “It’s the price of freedom,” he adds wryly. Like others who perform on a regular basis in some of the stations and connecting passageways of Montreal’s underground transit system, he prefers certain spots, and has learned to adapt his performance to the singular and changing demands of the moment. Different spots, as the designated performance sites are commonly referred to, have their own particular characteristics that buskers must work with and against, in a negotiated performance, an ongoing process of assembling and holding together. These various features include acoustic qualities, the amount of foot-traffic passing by, the physical lay-out of the space, ambient temperature and over-all comfort and security, proximity to one’s place of residence, and sometimes more personal attachments to certain spots. Some spots are near train platforms and are very noisy; others are windy, or freezing cold in winter. Some are extremely popular—it can be hard to get a timeslot there. Others are rarely, if ever, used. Many are only busy during rush hours, pulsing with the daily work rhythms of the city. Or, they may come alive on weekends or when there is a large conference, sports event, or concert nearby. “So, you do learn to adapt,” says FX, “but the most critical thing is: is the musician a good fit for that space, is the music pleasant in that space?” This attests to an understanding of busking as improvisational and self-consciously produced, not only in terms of individual performance, but also in relation to the social and material conditions within which the performance unfolds. As will be seen, the ethnographic methodology I employ in this research—particularly in terms of audio-visual recording and editing—is, like the creative assemblage of the busker, a process of bricolage, of working with the at-hand.

2. Methodological and Theoretical Positioning

In this article, I draw on three months of ethnographic research among Montreal metro buskers—musicians and other “street” entertainers, who perform in the spaces of the public rail system that runs under the city. My goal was to better understand what it

means, and how it

feels (in both a sensory and affective sense) to be a busker in the metro from the perspective of the performers. During this time, I spent some five hundred hours or more under the city. I rode trains, lingered in stations, and wandered the extensive network of corridors connecting stations to office and commercial complexes, downtown university campuses, and exits at the surface that can be as far as several city blocks from the actual station. I stood, sat, observed, conversed, took notes, filmed and made recordings of buskers and of the spaces of the metro. Conversations ranged from short informal exchanges (over two dozen) to semi-structured interviews ranging from fifteen minutes to over an hour (most of these were audio-recorded)

1. I spent many hours in subterranean coolness in the early days of summer, and oppressive heat, heavy and humid, later in the season. And, I watched, listened to, and was entertained by dozens of metro buskers. I also reflected on what was, in large part, the original inspiration for this research: my own past busking activities. This personal experience provided me with some insight into a busker’s perspective, and some knowledge of busking as a set of practices (a way of knowing and doing).

During the research, I played guitar and sang, at three different metro stations, performing a total of six times. In doing so, I was reminded that busking can be physically demanding and psychologically exhausting; and it can be deeply rewarding. It also emphasized the improvisational aspects of metro busking—for example: deciding what stations to play at and when (decisions made in relation to the availability of spots and travel time involved, amongst other factors); how long to perform for and the choice of materials played; adaptations such as extending a piece if there is a good response from passersby or cutting a song short if there is no one around; trying different strategies to engage passersby (e.g., making eye contact or smiling, positioning oneself, or the receptacle used for donations, to be more visible, or playing in time with the movement of the crowds, etc.); and, adapting to the material constraints and affordances of the performance spots—all of which are tactical responses in relation to the actions of others. This hands-on (and ears-on) approach of attending to the body—mine, as researcher, those of participants—is a central aspect of an immersive sensory ethnography (

Pink 2009), and is a way of entering into a close relationship with one’s immediate environment (

Imai 2008). In addition to highlighting the creative aspects of anthropological research, this insider perspective—the fundamental contribution of ethnographic participant-observation—provides for a more immediate, embodied knowledge, accessed by the actual practice of busking. Reflecting on these impressions allows for a deeper engagement with the world of the metro, and the experiences of metro buskers. This approach does not, however, imply a sensory equivalency between different bodies, or that two individuals will come to know the world in precisely the same way. Within the particularities of a given socio-historical context, how the world is sensed and what those sensations signify, is inextricably bound up with the social norms and cultural framework of that time and place (

Howes 2003). Further, within any social setting, not all beings sense in the same ways, nor do they all interpret those sensations in the same way. How individuals engage with, and produce, space is not fixed but ongoing and relational, thus containing the possibility for the new (

Lefebvre 1991).

Buskers, in the singular ways in which they engage with space and passersby, social conventions and legal regulations, acoustic challenges and affordances, exemplify the creative tactics of self-conscious agents engaged with their surroundings who draw on their own skills and experiences while “simultaneously improvising and striving to make things stick” (

Barber 2007, p. 38). For, as much as it is an individual activity, busking is a process of drawing together: a social assemblage that binds sense-perception and internal mental states within specific socio-historical processes and material conditions, of the world as we find it (

DeLanda 2006). It is a performance activity that, like music and creative activity generally, is unstable, always-in-the-doing—

cobbled together—in a continuous state of making (

Ingold 2013). Similarly, the ethnographic researcher, “must creatively and imaginatively improvise in the face of unexpected events” (

Humphreys et al. 2003, p. 14), suggesting parallels between busking practices and ethnographic research.

Reed-Danahay (

1993), in her ethnographic work among Auvergnat farmers, demonstrates how the farmers’ improvisatory tactics, known locally as “débrouillardise” (roughly:

making do,

figuring things out by oneself) reoriented her own understanding of herself as ethnographer and, consequently, her research outcomes. Likewise, I perceived a spillage of participants’ understandings and approaches to metro busking into my research: just as buskers must constantly adapt to conditions at hand, I had to adopt a strategy based on uncertainty, contingency, on-the-go adaptation—

of making do—to gain a more intimate understanding of the perceptions and experiences of metro buskers. I proceed from the assumption that this process of

bricolage—of improvised assembling—is a fundamentally creative act (

Le Loarne 2005). While my aims and methods, positioned within anthropological ethnography, differ from Roberts’ in his autoethnographic study of highway traffic islands (

Roberts 2015), I also link the concepts of assemblage and bricolage. Finally, attending to the bodily experiences of the researcher, as does Roberts, underscores the affinities between deep mapping techniques and the phenomenological anthropology of, for example,

Jackson (

2013) and

Ram and Houston (

2015).

3. Everyday Improvisation Underground

The metro is a space characterized, above all, by sound and movement. Trains come and go, ventilation systems drone, escalators rattle, winds blow through corridors, and the unintelligible barking of the public address system thickens the subterranean sound-world. Daily commuters negotiate their way through stations and corridors, mingling with panhandlers and tourists, transit employees and charity canvassers, street hustlers, idle teenagers, and others. This underground urban polyphony has its own timbres and rhythms, in counterpoint to the above ground. Buried under the city, it is easy to forget how directly connected the metro is to life at the surface. It is a space that may feel displaced and displacing, an infrastructural system upon which the city is deeply reliant but, that like so much of the technology around which our lives are centered, is largely taken for granted, dropping into the perceptual background (

Star 1999). Yet, it is an infrastructural space that is informed and reformed by human agents, in their everyday practices. Trains follow set routes, but commuters follow their own paths; architecture and regulatory apparatuses variously guide, enable, constrain, action, but individual actors delineate divergent pathways, create new meanings, appropriate spaces (see

Figure 1). Not simply passive subjects in a non-space of urban infrastructure, commuters are driven by their own desires, using time spent in transit toward their own ends, framed within their own understandings (

Bissell and Overend 2015).

Through repeated familiarity with stations and their locations throughout the city, metro users can develop an internal map relative to the above-ground. This embodied map represents a different spatial and temporal relationship with the city than does the more familiar street map—a thickening of spatial experience. Metro users know the city as not limited to the surface—its skin—but as extending down and laterally out: a parallel city, where one relies less on sight than sound and a kinesthetic sense, a bodily awareness of movement and depth. But, if a metro system seems a sort of world unto itself, it is nonetheless integral to the city as a whole, and every station has its own unique particularities in direct relation to the part of the city within which it is located (

Augé 1986). The proximity to workplace and businesses, educational and cultural institutions, the characteristics of the neighborhoods, all color life below ground and have an effect on the busking spots in the metro. Buskers know this and may adapt their practices accordingly. The co-productivity of body and space is particularly significant in terms of the acoustic environment of the metro. Hard, reverberant building materials (tile, concrete, steel) and architectural design (long corridors, massive vaulted halls, cavernous stairwells, etc.) produce a pervasive reverberation, the hallmark of the underground (

Labelle 2010), which may, variously, enhance or hinder a musician’s sound. Objects and materials are active participants in what is, in the case of musical performance and perception, an affective, sensorial, and fundamentally intersubjective social experience (

Schutz and Kersten 1976).

While all who move in the spaces of the metro contribute to its social—and sonic—character, buskers do so in a unique way, enacting a “liminal spacetime” of performance (

Bywater 2007) in which they may foster impromptu moments of social encounter. Buskers can be understood as creative agents who operate within but against planned space, “in which they sketch out the guileful ruses of

different interests and desires” (

De Certeau 1984, p. 34). The metro was built, in the first place, to move people rapidly and efficiently about the city, serving the functional needs of urban centers (primarily those of mature capitalism); it was not designed to foster creative engagement and convivial social exchange. Yet, this is precisely what may transpire when musicians and other public entertainers perform there (

Green 1998). “You make these transient little connections,” says Justin Kozak. “I think that has something to do with [the appeal of busking].”

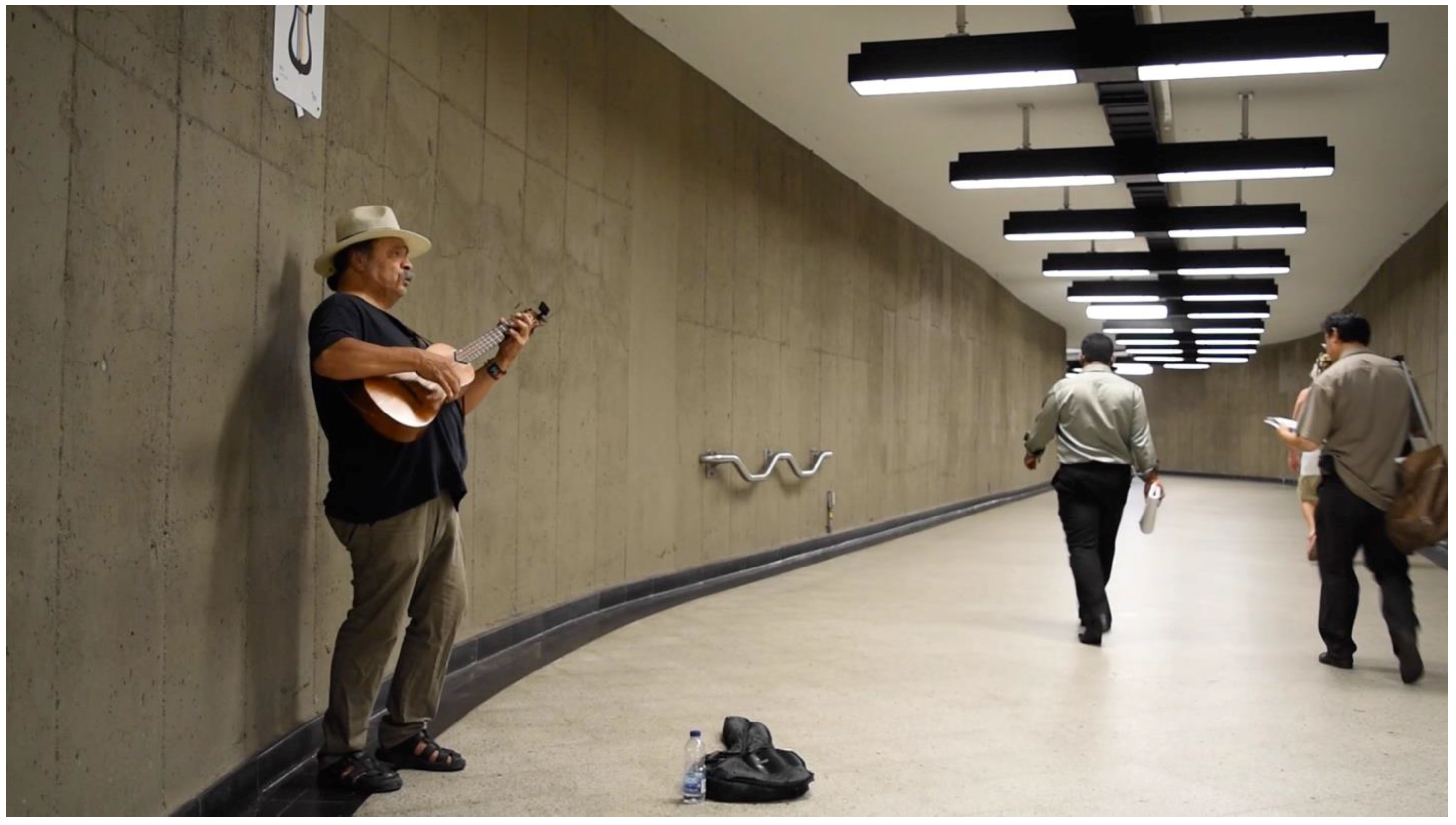

4. Encounter, Materiality, Gift

Buskers are far from uniform in their practices and reasons for performing where and as they do (

Marina 2016). There is no fixed formula or consistent descriptor, in terms of instrument, style, genre, or repertoire of metro buskers, whether they use electrical amplification or pre-recorded accompaniment tracks, how often they play, whether busking is a passing thing, or a long-time activity, and how much they might identify themselves as buskers, or their motivations for busking in the first place. Some do it primarily for money; most see it—at least as much—as giving something to the public, as contributing a shared pleasure and conviviality in a space that is typically felt to be decidedly unpleasant. And for a few, money has nothing to do with it: they may be practicing an instrument or simply doing it for their own pleasure. Some performers conceive of busking explicitly in terms of a gift to the public and of creating unexpected moments of social encounter (see

Figure 2). Coralie, for example, spoke of “making music more accessible to the public” and of the pleasure she derives from this. For Alexandra, there is sense of “contributing [to a] pleasant mood… [that] is reciprocal” because the recognition and appreciation of passersby bolster her performance—a give-and-take between performer and passersby, within the framing of metro acoustics, legal regulations and social conventions concerning public performance, music, and creativity. These examples emphasize busking as a relational, embodied, performance-as-gift—one that may in turn engender new social and material relations of encounter, and of

Gift (

Sansi 2015).

This understanding on the part of many research participants coincides, in many respects, with Mauss’ concept of the

Gift (1967) that enacts and expresses processes of social and material circulation. However, in the case of street performers, there can be no question of a counter-gift obligation: the gift of the performance is freely given. While it may be hoped that this is acknowledged by passersby—financially or otherwise—there is no expectation that it must, or will be. “When you’re playing in the metro, you’re sort of intruding on the little world [of passersby]… they didn’t ask for you to play there,” says Conley. “They don’t owe me anything.” And yet, many participants spoke of busking specifically in terms of giving to the public. FX sees busking as “a form of exchange” with the public. Yet, even when this exchange centers on money, there is often a conviviality between performer and passerby, indicating how the social (micro-social moments of encounter, of mutual recognition and acknowledgement) and the material (money or other gift-donations) are completely intertwined (see

Figure 3).

In his discussion of the

kula circle,

Mauss (

1967) underscores the ongoing cyclical nature of the exchange—and that it must be continually maintained and renewed. An act, an exchange, even when expressed within existing social forms (e.g., the

kula circle, or busking regulations and conventions), must always be performed, simply to

be. As with social space, the act that defines and requires that space must always be

re-performed; thus, there are always possibilities for novel variations (

Rose-Redwood and Glass 2014), of genetic mutations that may transfer to subsequent performance-acts, suggesting creative possibilities in the performance that may be generative of new social acts. Busking, then, is a relational process involving much more than simply the gift of performance in exchange for potential appreciation and recognition (monetary or otherwise). It may produce new trajectories of becoming that entangle diverse agents in unforeseen ways.

Klank first started busking in the metro playing a pennywhistle, “But,” he told me, “what I really wanted was a trumpet”. He already had a mouthpiece, so he busked with just that. “I’d cup my hands to be like a mute [affecting the tone rather than the volume].” He demonstrated this, playing a range of songs with surprising agility. Here, we see the individual performer working with what he has at-hand but driven by other desires, beyond that which presents itself. “I was just [busking in the metro] to try and make enough money to buy the trumpet,” he says, laughing. “I had a sign that said:

Please help me buy a trumpet.” It took about four months to earn the required sum. “So that was it…I wasn’t going to busk in the metro anymore. But, then I felt like: All these people helped me to buy my trumpet…I wanted to thank them, and show them where their investment went…” His original intention for busking was both occasioned by, and culminated in the object of the trumpet, which, rather than signaling the completion of this process of circulation, was the catalyst for an expansion of the trajectory of his busking practice. Here, we might identify a process of “entrainment” (

Bauer and Kosiba 2016), whereby material objects participate in social action, enlisting other objects in the process: Klank’s desire becomes the mouthpiece’s desire for the body of the trumpet. Yet, this need not imply a flattening of power relations, of equal agentic action. Surely the entire process—desire, action, reward, new cycle of action—is initiated in a foundational moment (“What I really wanted was a trumpet.”) by the actions of “key movers” (

Appadurai 2015, p. 234)—Klank himself, in this case. This illustrates that, although materials and objects are understood as active participants, the busker assemblage itself is predicted on the actions of a sensing, knowing social agent—the busker—belying a leveling of relations, or equivalency among the various participants. Acknowledging a multiplicity of actants does not negate power and difference. Allowing for a plurality of voices has been central to the ethnographic enterprise, ever since the so-called crisis of representation (

Rabinow 1986). In my fieldwork, I attempted to allow diverse actants—in addition to the actual busker participants—to come to the fore, by attending to the material features not only of busker practices

per se (e.g., instruments and other equipment) but to the affordances and constraints of the physical spaces of the metro system. The task of the ethnographic anthropologist, as of the artist, is the assembling—the cobbling together—of these many features and participants, a creative act of bricolage with some form of durability (

Kelly 2008).

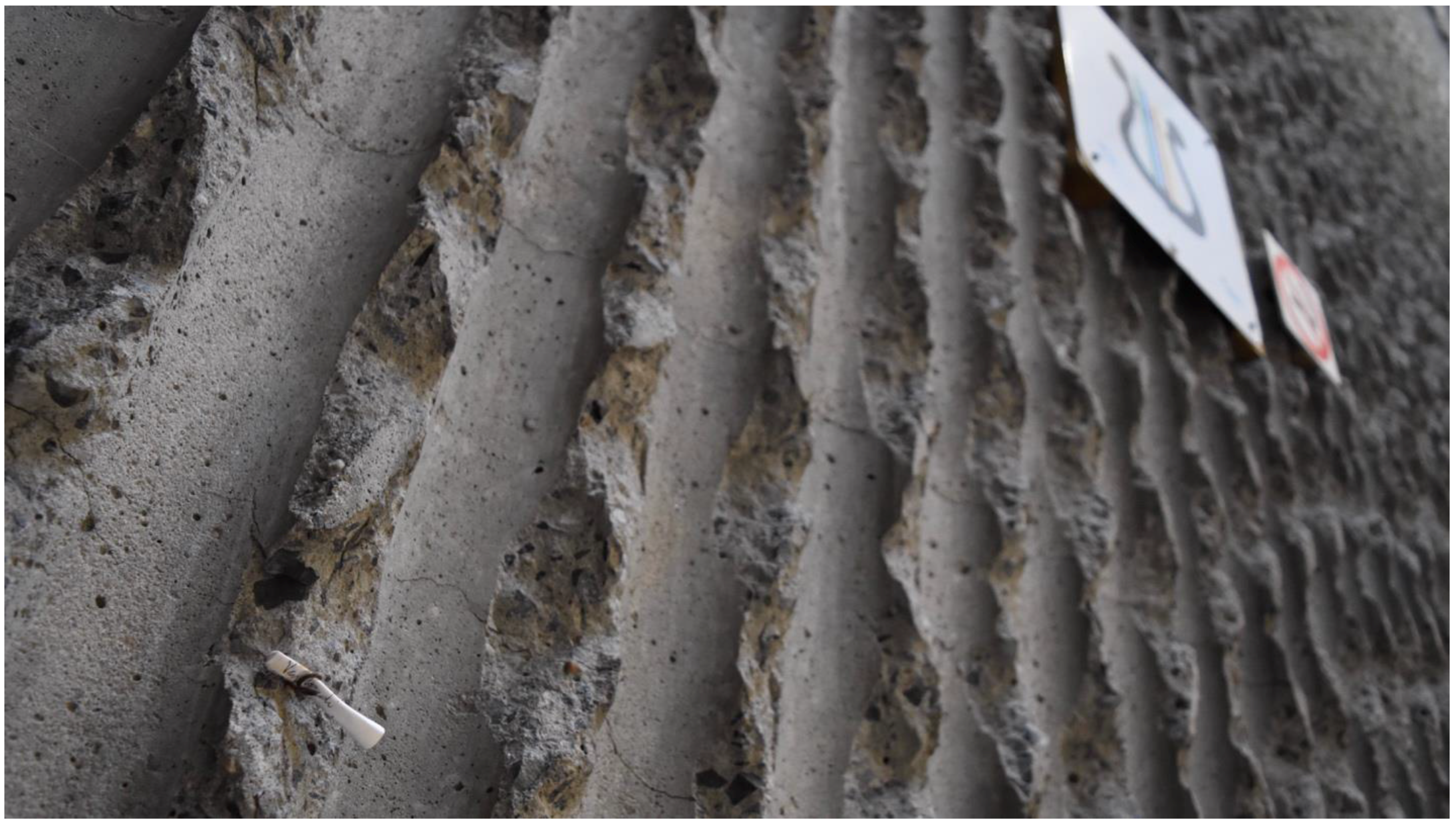

5. Performing Space

No permit is required to perform in the metro, but one may do so at designated spots only; these are indicated by a sign depicting a stylized lyre (see

Figure 4). Each spot has its own characteristics, and most buskers prefer certain ones for their own reasons: potential audience and earnings; matters of convenience, such as proximity to home or work; the overall sound qualities, etc. The degree to which buskers consciously adapt to the characteristics of a spot varies greatly. Conley says that she has gotten to know the frequency of the trains as they change throughout the day at different stations, and will time herself partially in relation to these. In a long corridor at the lowest level of Berri-UQAM station, commuters stream past the busking spot there, with lulls in between departing and arriving trains. Many who perform there take short breaks during those lulls, and start up again when prompted by the sound of approaching footsteps and voices.

Some buskers seem to give little thought to interacting with passersby or even making eye-contact (in a couple of cases, I observed musicians wearing dark sunglasses that hid their eyes; neither, however, appeared to play frequently in the metro). Other buskers make a point of trying to catch people’s eye but make sure not to hold their gaze for too long, so as to not cause any discomfort for passersby. One regular at Guy-Concordia station hardly ever looks up or even seems aware of the coming-and-goings all around him. Another musician complained that she had to practically step around him to get to the sign-up list tucked behind the lyre sign (used to reserve a time-slot). Regulations prohibit performers from standing directly in front of the sign—they cannot impede someone else from checking the list—but they must be near the sign, with equipment occupying a space “less than 2 m in length and 1.6 m (5 feet) from the wall behind”

2—likely one of the most precise measurements of busking practices. Most buskers stay close to the sign; a few stray slightly farther. All stay within a distance that cannot be accurately defined yet is simply known to all—a spatial recognition of the sort that becomes an implicit bodily knowing, internalized and reproduced through habituated social behaviors (

Mauss 2006).

Some put considerable thought into where they place their receptacle for donations—a hat, instrument case, bucket, etc.—and how they position themselves in relation to the surrounding space and the flow of passersby. Klank, who is blind, chose his metal bucket so that he can hear when coins are dropped into it—cueing him to bow in recognition. Alexander Shattler (a dancer, and only non-musician participant) uses a bright blue plastic bucket, selected for its visibility (see

Figure 5). He makes the bucket the fixed point around which his performance unfolds, deliberately drawing attention to the bucket, always adapting his dance to the movement of passersby. He constructs a stage-like performance space in relation to the bucket, then breaks through the invisible barrier of the “fourth wall,” inviting passersby to also engage in this subversion of habituated spatial practices, suggesting a co-participatory sense of spatial bricolage. He talks about picking up on the “rhythm of people going by.” “You’re right in it,” he says, “you can kind of change [the rhythms],” suggesting how buskers may redirect commuters’ social and sensorial trajectories.

Another participant says that all street entertainers are responding to a public need. “It’s more than a material need,” he says, “[You] are producing something right there...It’s live.” Public artistic performance can be seen as a constructed situation that precipitates new socio-material relations—a mutable and mobile scene of encounter centered on and expanding from performer and performance. The busker both

brings into place—spatializes—the spot, and is

emplaced there—is, to a degree, produced by the spot, in terms of its acoustics and other physical characteristics, the relations with passersby, the legal regulations of space, etc. Although it is materially fleeting, the performed space/space of performance assumes a durability for the duration of the performance (

Boetzkes 2010)—less a site than process of becoming, that is transitory, in transit, and potentially transformative.

The busker, in participating in the everyday social and material life of the metro with body and instrument, is informed by particular spaces and iteratively (re)performs them, subtly reconfiguring how they may be experienced—by others, but at the least by themselves: a novel assemblage-experience. Similarly, I did the same but, instead of with a musical instrument, with camera and microphone I explored, probed, recorded spaces and performances, and these in turn were shaped by and shaped my partial perspective. The re-configured space, in this case, extends into the digital realm, with the production of a sequence of busker videos

3. How I engaged with the physical space of the metro while filming (from framing shots, to avoiding being stepped on while shooting from floor-level as commuters streamed by at rush-hour) and making audio recordings involved constant adaptations and re-appraisals (many spots have a strong reverberation, and almost all are typically described as noisy). The videographic output within my research emerged initially out of a series of improvisatorial tactics in which my own bodily experience of space was central but was one that also brought into focus the participatory role of material actants. Just as infrastructures and objects actively influence human experience (

Larkin 2013), the technologies of engagement (pen and paper, film camera, digital recording devices, etc.) are not neutral devices, objectively recording and reproducing lived human experience; they have their own limitations and potentialities in the spatial performance. In both the case of the busker and of the ethnographic videographer, the performance underscores the inter-relations of body and technology, self and space, and self and others, and presupposes performance as a form of embodied knowledge (

Brashier 2013). The busker’s practice unfolds within existing social norms while simultaneously expressing individual life courses, including, but not limited to, musical training. The ethnographic videographer draws on academic and technical training (which, as with that of the busker, may be extensive or quite limited), suggesting that both busker and videographer are situated practices, unfolding within existing ways of knowing and doing while also delineating their own subjectively embodied positions (

Van Wolputte 2004).

6. Spatial Acoustics and Creative Tactics

The degree to which buskers modify their performance to the particular demands and affordances of different spots is both individually motivated and always a process of adaptation to specific and changing conditions (see

Figure 6). This is especially true in terms of acoustics. Some musicians note how the acoustics of a space change with the number of people moving through. One particular challenge, as FX notes, is not knowing how you sound to others, especially from a distance. Often, it is a matter of guesswork, of estimation; but, many of those who busk regularly develop a certain sense for the acoustics at their usual spots. Geof Holbrook is very conscious of the spatiality of aural perception. “When I see a group of people coming, I know it sounds very different to them when they’re farther away than when they’re close.” He says he sometimes models his playing on the movements of passersby within that particular space. “I’ll play very very slowly when they’re far away… and as they’re coming, I’ll start to speed up…and I start to quiet down,” he says. “So, it’s like this mobile audience…and so you adjust in real time as they go by.”

Ben Evans says that he plays more fast-paced music at Guy-Concordia station, where the window in which passersby will hear him is less than a minute, whereas at spots in long corridors the pace is a little slower, and he adjusts to this. Like Geof, he is conscious of the rhythm of the movement of passersby, and likes to play in time with these rhythms. “Sometimes I’ll speed up if someone runs by…fun little stuff like that.” Another way in which he adapts to the conditions at hand is altering the tonal settings on his amplifier. One of his usual spots is at Square-Victoria-OACI station, in a long brick-lined corridor where low-end frequencies dominate, so he adjusts his tone accordingly, cutting back on the bass frequencies and increasing the treble slightly. But, when he arrives to play at Guy-Concordia, his guitar sounds thin, flat, and he has to change the settings again. Similarly, at Place-des-Arts station, Effem, another guitarist, turns his amp to face the wall directly behind him, otherwise the sound bounces off of the wall about five meters in front, oversaturating the narrow space; but, if he simply turns down the volume, he gets drowned out when a large group of people pass by, all talking. He is an extremely skilled musician, who plays instrumental pieces on a steel-string guitar, coloring them with improvised lines and harmonic ornaments. His preference is for spots within the controlled area of the metro, in part because of the more constant ambient temperature (of special concern in the winter). He often plays during the morning rush-hour, and feels that the music he plays, which is both energetic and soothing, is likely more appealing than something more upbeat or intense.

Other research-participants say that they vary their repertoire to some degree depending on the time of day, the station they are playing at, even the day of the week or the season—all of which influence the make-up of potential audiences. Several metro buskers talk about the improvisational nature of busking—in everything from what to play and when, to how they interact with passersby, to securing a spot to play. Most who perform regularly in the metro head out early in the morning to try and sign up for a time at their favorite spots. On the other hand, some buskers take a more spontaneous approach. “I was just passing by, and there was no one at the spot,” a musician at Jean-Talon station tells me. “Since I have my instrument with me, I figured I would play here for a while…it’s good practice.” Gérald Cabot, who has been playing in the metros since the early 1980s, says that there is nothing predictable about busking. “One day, you get a great response, and you might play the same thing at the same spot another time, and…nothing.” Another seasoned busker tells me: “Busking is not a perfect science.” Then, reconsidering, says: “Actually, there is no science to it: you’re always kind of guessing. How much you try to adapt depends on the person.”

During fieldwork, I travelled between stations with only a loose trajectory in mind. Although ethnography has a long history with its own disciplinary traditions, it is also an ongoing process of trial and error, of improvisation (

Cerwonka and Malkki 2007). Sometimes I operated more on gut-instinct than from a concerted plan; this was particularly true in terms of locating and recruiting participants. Busking is, by its very nature, a highly mercurial practice, characterized by spatial and temporal transience. I had to operate accordingly in my fieldwork, never knowing for certain where I would be during a particular day or who I might encounter (or possibly not encounter any buskers, as happened on a few rare occasions). Most buskers cannot say for certain where and when they will be playing the next day, let alone in a week. Often it was a matter of hit-and-miss: sometimes I was lucky enough to meet someone who was ending a set and was interested in participating, but this was rare. More frequently, it was a case of catching them at just the right time, or arranging to meet for an interview at a later date. One of the appeals of busking is that one has the freedom to play as much or as little as one chooses. “It’s like: anytime you want, we’re ready for you. Here’s your audience, they’re already here,” says Justin Kozak. On the other hand, buskers must negotiate the demands of legal regulations and engaging the public, of spatial acoustics and financial viability, among other considerations. Improvisation, then, is not an unbounded free-for-all of possible actions; rather, it is an ongoing process of negotiation within largely known terrain, but without quite knowing what will come next, where the next step will land (

Ingold and Hallam 2007). This element of uncertainty and adaptation is to be found in the tactics of both busker and ethnographer, and reveals linkages to the wider environment within which these acts unfold.

7. Subterranean Assemblages: The Wind

The spot by the Saint Catherine street exit at Berri-UQAM station is popular with many buskers, despite particular drawbacks. These relate to two spatial/physical aspects of that spot. The first is architectural. The general lay-out is very favorable for busking: at an L-bend in a corridor, at the bottom of the stairs and escalators to the surface, with lots of space in front of the performer, where passersby may linger for a few minutes. Because it is quite a distance from the actual train station, it is relatively quiet—adding to its appeal. But, it is subject to the recurrent winds prevalent in so many stations: winds that blow down from the city above; winds from trains in tunnels further underground; displaced air, moving through long passageways, forced into doorway bottlenecks, gusting out onto open platforms. At some spots, the wind is nearly constant, varying only in intensity. At others, it comes in intermittent blasts, as steel and glass doors exiting to the street are pushed open, allowing more air to rush through. Challenges caused by the wind include signage and music stands blown over, sheet music carried away, hair blowing in the face. Several buskers mention its dehydrating effect, or that it can de-tune an instrument, or just generally be unpleasant. The second complaint about this spot concerns its location within the city. The exit is at the corner of Place Émilie-Gamelin, a park that has long had a reputation of being frequented by the homeless, the mentally ill, and dealers and users of street drugs. With historical roots in Europe’s itinerant musicians (

Cohen and Greenwood 1981), busking is itself associated with life on the street (

Smith 1996). Some passersby may equate busking with begging; but, according to a few key research participants, this perception is diminishing.

The park has been undergoing a beautification program, including summer festival concerts and the creation of a community garden, and served as a gathering site for protesters during Montreal’s student strike of 2012 (

Diamanti 2015); but, it continues to be a hub of activity for a large number of downtown Montreal’s street-affected individuals. This translates into a prevalence of panhandlers inside the metro, in addition to those who may simply have nowhere else to go. One day, while I filmed a duo there, a man began pacing back and forth in front of the two musicians, swinging his arms in time with the music, “singing along” to the song—though it was more of a talking-singing, in a steady stream of barely comprehensible French. Part way through the song, the musicians stopped and angrily demanded: “What are you doing? What do you want?” (I stopped filming). They eventually entreated him to leave, but ten minutes later he was back and resumed his semi-musical rapping monologue. One of the musicians finally got up, took him gently but firmly by the arm and, ignoring the man’s loud protests, walked him part way down the corridor, telling him to clear off (which he finally did). This was a rare overt conflict, in which the two buskers had to improvise in their dealings with unforeseen—and volatile—conditions; but, as noted, how a day of busking goes is anything but predictable.

Coralie sits on a cloth spread out on the floor, just past the protruding angle of the L-turn, where the corridor leading into the station narrows. The sound of her harp, with the help of a small amplifier, fills the space. It is rich and warm, and some notes ring out with bell-like clarity. The wind is a special challenge, for her. It detunes her harp (see

Figure 7)—but, much worse, it can cause the strings to start vibrating, producing a tone. This is the principal of the Aeolian harp, an instrument “played” by the wind: air moving over and between the strings causes them to vibrate, and a vibrating string produces sound. Sound is, in fact, the movement of air pressure, a vibrational force moving in air, that arrives at a sensing system, such as the human auditory complex, and is reconstituted as intelligible sense experience (

Rumsey and McCormick 2009). The wind picks up as I start filming; soon the strings of her harp are vibrating audibly. She pauses in the middle of a piece to place both hands across the strings, bringing the mounting, droning hum to a stop. “It’s really a problem,” she says. “The wind blows in, down the stairs and hits the wall right here where I’m sitting.” I walk over to where she sits and note that it is less windy directly facing the stairs, where I was filming from. She moves and confirms my sense, adding “and the light is better here, too.” She sets up there and resumes playing. As I shoot more video, I reflect on this effect of the wind: how it binds performer and physical performance space, altering the details of particular busker practices and expressing a “material agency” of infrastructure (

Dominguez Rubio 2016), with metro architecture complicit in the busking assemblage. And, I consider how I, too, have been drawn in by the wind: by being there to observe and film, I become implicated in, and alter, the performance (an example of the ethnographic encounter as a dialogic process of engagement, an ongoing open-ended conversation with varying participants and degrees of participation). But, when I go up to street-level, so as to get a shot of Coralie as I come down the escalator, the complexity of the wind as assemblaging event is made further visible.

It is not uncommon to see a panhandler holding the door for commuters in metro stations, most often proffering a cup for donations. This presumably suggests that a service is being offered in exchange for which passersby may choose to give some money. A man with weather-worn skin, a slight hunch, grey stubble on his face, and fingers stained from cigarettes, grime, and the weary life of the street, stands inside the station, one hand holding the door open for all who pass by, the other gripping a dirty paper coffee cup. And it is this open door that allows air from the street to come rushing in, down into the passageway below, gathering force where it hits the wall and squeezes into the narrower corridor past the turn, transforming Coralie’s performance in the process. Actors blur into each other. Musician, instrument, panhandler, observer, performance, space: all are caught up in blowing currents of air and flows of becoming. Movement pervades all, as differing rhythms overlap, resonate, conflict, break apart. The wind can be understood here as a mediating presence, an actant unto itself, the “glue” that momentarily holds together, as well as being the field of action in which sense-perception unfolds. It binds, in its turbulent movements, all manner of people and things, yet possesses little in the way of substance itself: it is the movement of air in relation to other things, changing air pressure in space. And that is also, precisely, what sound is: a vibrational movement of air. But, we can only call it sound when there is a hearing, perceiving subject. Likewise, the wind, though purely a relational process between other actants (people or otherwise), is an assemblaging force that temporarily binds and makes visible various actors and features of the daily world of the metro. It is at once a modifier and a material manifestation of social relations—one which metro buskers must contend with, in a continual process of negotiated action.

8. Expanding the Field: Montage and Material Agency

Just as the camera fosters a “close personal relationship with subjects” (

Grimshaw and Ravetz 2009, p. 6), it entails one also with objects. The capacities and uses of digital technologies alter our perception of our surroundings, “dramatically chang[ing] the life of the senses” (

Howes and Classen 2014, p. 92) and how we engage with the world around us. Not unlike the busker who engages with varying, and at times unpredictable, material conditions, the audio-visual production in this research was a process of continuous modifications, of working within conditions as I found them. In filming, I paid conscious attention to the architecture of the spaces, including the actual building materials and the objects and materials used by buskers in their performance—the “thingness” of busking. Taking dialogic art as site, means, and product of a constructed moment of engagement,

Calzadilla and Marcus (

2006, p. 103) argue that such an encounter can result in an “othering of the self”—a blurring of the lines between self and and other, and self and space. This emplacement of “sensory space [within] social space” (

Lefebvre 1991, p. 210) posits the self as a situated, reflexive subjectivity, constructed in relation to other sensing subjects (

Merleau-Ponty 2012).

As the acoustics and other architectural features of the performance spaces play an active role in the busker-assemblage, they were, consequently, central to the audio-visual production. I experimented with various shots, changes of focus (so as to emphasize various details and the movement of passersby), and other creative—and often haphazard—techniques, including: multiple angles, to try and capture an overall sense of the metro system; close-ups of musicians’ instruments and hands, or of architectural details; wider shots, so as to convey a sense of the performer as “emplaced” within the particular site; footage of trains and moving crowds; etc. The crowd shots were mostly made at floor level, in corridors or near train platforms, for two reasons: to avoid making passersby identifiable, and to capture the sense of movement that is integral to the metro. Consequently, I had to work with architectural demands and the movements of passersby, all in relation to the performing busker. In the process, my position as researcher is thus defined as much by the at-hand—by the field—as it is by any previous training, disciplinary exigencies, or research design: ethnography as a process of

becoming, of unfinished story-telling, of assemblage (

Biehl 2013). Although I entered the field with a detailed research plan, I knew that it would have to be adapted to changing situations—that ethnography is enriched by improvising with the at-hand as conditions and aims modify and are modified (

Dequirez and Hersant 2013). I aimed, from the outset, to produce an audio-visual work representative of the experiences of metro buskers—a context in which the ethnographer is both analytic researcher and creative producer (

Boudreault-Fournier and Wees 2017). My goal with this audio-visual production was twofold: as material for analysis—documentation of events as they unfold, which can include many details lost to, or perceived differently during direct observation (

Simpson 2010)—and as material from which to produce an audio-visual work that might convey something of the sensory experiences of buskers, and of being in the metro, more generally. I had in mind less of a didactic ethnographic documentary form than a more creative, impressionistic approach, influenced by an anthropological engagement with experimental film (

Schneider 2011). However, due in large part to the unforeseen influence of some musicians and technical challenges, what I made was essentially a dozen music videos of buskers (see:

https://vimeo.com/wees). This may have benefited some of the participants as much as it did the overall research outcomes, suggesting a potential spontaneous gift-relation integral to the ethnographic enterprise.

When I filmed participants, I asked them to ignore me, as best they could. They were all very obliging. I was more focused on the details of their performances, within the particular context of that space, than recording entire pieces. On two occasions, however, participants asked me if I would film them playing a certain song, from beginning to end. I was happy to do so, but later, as I started to edit the footage, I felt an obligation to produce something “nice” for the participants (that I, at least, would find aesthetically pleasing), in recognition of their time given to me, signaling a shift in the outcome of the video production in this research. I spent many hours “cleaning up” the audio (as noted, the metro is generally a very noisy place), and given my limited skill and experience as a videographer, much of the footage was of very poor quality. Consequently, the editing process assumed a greater prominence than foreseen and became itself a site of engagement and improvisation—suggesting a multi-sited ethnography (

Marcus 1995) that may extend from the initial field-site to the video editing suite. As I worked through the many hours of audio-visual recordings I had made, I decided to make a few more short videos of buskers playing a single song (or an edited extract of a longer piece); pretty soon I had done so for more than half of the research participants, and I again adapted my aims and techniques, finally producing a dozen short videos of metro buskers rather than the longer, more experimental work I had originally envisioned.

Editing is a creative, not merely technical, aspect of film and video production (

Marcus 2013). Reviewing the material I had, and producing the finished videos, was not a linear, systematic process, but more of a creative throwing together—less of a formal logic than an ongoing guesswork and assemblaging process. Experimenting with the footage, I was guided by a montage approach—the juxtaposing of seemingly disparate elements, making visible aspects of time, space, social processes and human experience that normally go unseen (

Willerslev and Suhr 2013). The elements that are “thrown together,” that inhabit the two sides of the cut, may be whole images or specific image qualities (such as colors, forms, or actual objects). They may also be acoustic features, suggesting additional creative possibilities in musically-centered digital audio-visual production (

Boudreault-Fournier 2016). Montage techniques can rely on analogy and similarity to suggest what is present but hidden (

Stoller 1992) but can also, by stitching together images that may startle and shock by their seeming incommensurability, produce new meanings, new creative possibilities (

Gardiner 2002). In some instances, I worked with the audio recordings I had made so as to emphasize certain aspects of a performance or a site—for example: using multiple recordings of a performance made at different distances, with different microphones, and blending these with the noise of trains, passersby, and the natural reverb of the space. In some cases, I spent a great deal of time working on the audio recordings, and in others very little time, as the acoustic features of performances and sites carried over into the editing process. I take this as further evidence of material influences extending beyond the original site of the ethnographic encounter.

Working through the challenges of learning new—to me—editing software, with footage of variable quality, I became increasingly aware of how material participants shaped my actions, just as they do buskers’ performances. The videography in this research became a bridge between my performance, as ethnographic researcher, and that of the participants, highlighting the inter-relations of the social and the material. Both in the field and in the editing stage, the video production was a process of creative engagement and a means to an end, with the final videos posted online and which then became catalysts for new trajectories of circulation (within the digital realm). What also came into view, during and after the editing stage, were the parallels between the busker-performer and my role as a researcher and creative producer. These show ethnographic research itself to be a form of assemblaging, of bricolage—a performance that, like that of the busker, is strategically patterned at the outset but improvisatory in the doing.

9. Conclusions

When a busker tells me “It’s a beautiful day, the mood is good…I feel it and I give it back,” this presents the gift-exchange between busker and passerby as a socially mediated emotional experience, suggesting an embodied subjectivity that is sensorially and affectively individualized and unequivocally context-dependent (

Biehl and Locke 2010). It is a performance that is as corporeal and material as it is social. The playing of an instrument, the vibration of vocal cords, the perception of sound, the movement of bodies, a coin tossed into an instrument case, a smile and a bow, the acoustic participation of tile, glass, cement, steel: it is at the confluence of these particulars, and others, that the act of

being busker is made visible, and audible. The metro itself is an assemblage of diverse, changing elements, mediated through the memories and imagination of the individual actors who move through its spaces. The busker is, likewise, an assemblage-event, temporally and spatially localized at the convergence of multiple lines of flow (trains, commuters, sound waves, circulations of currency, changing regulations of space, etc.), not a fixed identity or subject-position. Yet, while metro architecture participates in busking practices and perceptions, without a perceptive apparatus endowed with a reflexive awareness and encultured system of meaning, of making sense of the world—in other words, a living human body—there “is” no music, no occasion for social encounter and exchange. Without a performer, there is no performance.

Busking, as a set of practices, is—like the “ensemble of procedures” that characterize everyday life (

De Certeau 1984, p. 43)—dispersed yet situated (

emplaced), never complete, always in the process of being made and unmade. Rather than being seen as a profession, identity or bounded subject-position, busking should be understood as an assemblage-act, involving multiple participants—human and material—that emerges through the practices and creative tactics of an individual performer, in an ongoing process of cobbling together, of

bricolage. Finally, as I have argued, sensorially-engaged ethnography is itself a creative, improvisational process, guided as much by the conditions at hand as by an overarching research design. This suggests that ethnographic research itself may be understood as a relational, embodied, assemblaging activity, involving multiple participants (human and material), with the ethnographer as

bricoleur, who—like the busker—draws on, and momentarily binds together, multiple social and material trajectories of becoming.