Abstract

This article offers a textual “deep map” of a series of experimental commutes undertaken in the west of Scotland in 2014. Recent developments in the field of transport studies have reconceived travel time as a far richer cultural experience than in previously utilitarian and economic approaches to the “problem” of commuting. Understanding their own commutes in these terms—as spaces of creativity, productivity and transformation—the authors trace the development of a performative “counterpractice” for their daily journeys between home and work. Deep mapping—as a form of “theory-informed story-telling”—is employed as a productive strategy to document this reimagination of ostensibly quotidian and functional travel. Importantly, this particular stage of the project is not presented as an end-point. Striving to develop an ongoing creative engagement with landscape, the authors continue this exploratory mobile research by connecting to other commuters’ journeys, and proposing a series of “strategies” for reimagining the daily commute; a list of prompts for future action within the routines and spaces of commuting. A range of alternative approaches to commuting are offered here to anyone who regularly travels to and from work to employ or develop as they wish, extending the mapping process to other routes and contexts.

1. Introduction

In 2011, we set up Making Routes; a network and online resource for researchers and practitioners working with mobilities in contemporary performance [2]. We organised a symposium at the Arches arts centre in Glasgow [3], and ran a series of events including Phil Smith’s Misguided in Ayr [4]. Our interest in journeys continued independently, with the occasional opportunity to exchange ideas and discuss our various projects. We think that the idea of working together was always there, but it was not until September 2013 that we decided to collaborate on a research project. At the beginning, neither of us was clear on what that might be. We thought we might travel somewhere together, or make a performance about journeys. We started without a destination in mind, which is probably the best way to start.

Lacking a clear direction, we found it difficult to make time to work together, and with both of our lives including full-time lecturing posts and long commutes, we were initially anxious about when we would be able to embark on the journeys we wanted to take: Laura travels by car, ferry and train every day from Innellan on the West Coast of Scotland to the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) in Glasgow; David drives from Glasgow to the University of the West of Scotland’s (UWS) Ayr campus. It was for a practical reason, then, that the first stage of this project was for us to accompany each other on our commutes, and it was during these specific and purposeful journeys, and the subsequent meal at each other’s homes, that we started to think critically about our daily, repetitive mobility. Laura kept a research diary of these initial conversations:

Tuesday 24th September 201317:25 train, 18:20 boat, arrive home at 19:00The train is busy. David and I travel back to my house together to talk about our project. David tells me that his commute is very different as his is solo in a car while mine is mainly made up of public transport surrounded by other bodies and has four different stages. We talk about lots of things that are going on in our lives (work, relationships, performances we have seen) but we don’t talk much about the project until we are at my house and having some dinner that I have prepared the night before. We come up with some areas to research and both agree that doing each other’s commutes is an important part of this process. We arrange for me to do David’s commute on the 7th October and through this conversation I see my journey through David’s eyes. I drive him to the ferry at 20:45 and David travels back to Glasgow alone [5].

Our discussions around this project encouraged us to consider documenting our commutes as times and spaces of possibility and creative resistance—a way of reimagining aspects of the working day. This article focuses on the first stage of this process—an attempt to develop a “deep map” of our experiences-so-far.

Commuting has often been dismissed as a “desensitising” experience in which Sennett identifies a “disconnection from space as the body moves passively” through urban roadscapes ([6], p. 18). Likewise, Jean Baudrillard refers to the “effortless mobility” of car journeys ([7], p. 66); and Michel de Certeau points out the “immobility” engendered by train travel ([8], p. 111). In the field of transport studies and policy, the perception of commuting as a “problem” has led to an assumption that travel time is inherently unproductive ([9], p. 81). As Patricia Mokhtarian points out, as a result “virtually all of our policies, planning, and models are predicated on the assumption that travel is a disutility to be minimised” ([10], p. 93). However, others have recognised greater complexity in the experience of contemporary mobilities, which involves an uneasy combination of “experimentation and danger, possibility and risk” ([11], p. x). Identifying this complexity in our everyday journeys, we are interested in capturing our commutes as far more active and embodied experiences than the unsatisfactory interpretations of many critical representations, and transport policies. Like Tim Edensor, we distrust the popular perception that the commuter is “a frustrated, passive and bored figure, patiently suffering the anomic tedium of the monotonous or disrupted journey” ([12], p. 189). Instead, we are interested in the potential of travel time as a “gift” that is “a desirable time for many people” who value the opportunity to transition between modes of living and working, and to take “time out” as a retreat from external demands ([9], p. 88).

In the sections that follow, we present a “deep map” of our explorations into our daily commutes as fertile ground for creativity, productivity and transformation. We present a series of autoethnographic narratives, documenting our alternative commutes, which we undertook initially by walking, and then by cycling, swimming and boating the route between our homes and our places of work. Together, this interconnected web of personal account, anecdote, critical reflection and reminiscence, offers a textual map of these regular routes. Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks identify the potential of such a map—a form of “theory-informed story-telling” ([13], p. 16)—to contain juxtapositions and interpenetrations of the historical and the contemporary, the political and the poetic, the factual and the fictional, the discursive and the sensual; the conflation of oral testimony, anthology, memoir, biography, natural history and everything you might ever want to say about a place ([14], pp. 64–65).

This approach “attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of a location” (our italics) ([13], p. 15). However, for this project, we are interested in deep mapping a route. This process attempts not only to map—to record, document, represent—but also to engage with our commutes actively through a performative engagement with landscape; mobilising a variety of experiences that work against the “desensitising” systems of contemporary mobile life. Our approach draws on the “mobility turn” in the field of performance studies, and recent research into “a wealth of performances and related cultural practices [that] have been, and continue to be, actively engaged in imagining, exploring, revealing and challenging experiences of being in transit” [15]; ([16], p. 1). Fiona Wilkie recognises the affective quality of performance in this context, as “performance not only responds to but can also produce mobilities, reshaping existing models and engendering new, alternative possibilities for movement” ([16], p. 2).

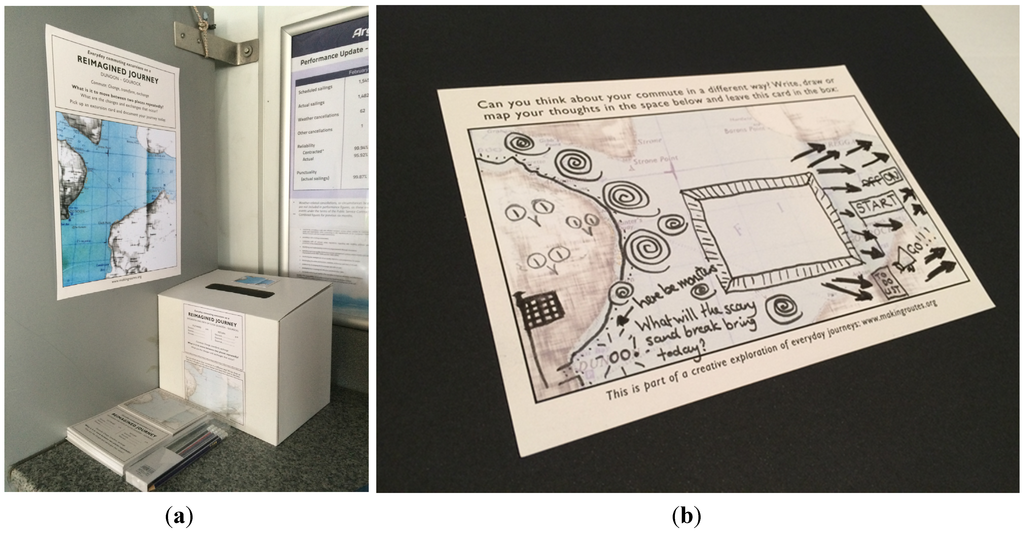

Importantly, we do not see this particular iteration of our project as an end-point. As such, we have aimed to leave our discursive map open ended, developing a series of experiments and “strategies” for reimagining the daily commute and extending our mapping project beyond our own journeys. These take the form of a postcard project on the Gourock to Dunoon ferry route (see Figure 1) and a list of instructions, which we offer here to anyone who regularly travels to and from work to employ or develop as they wish. Similar to Carl Lavery’s 25 Instructions for Performance in Cities [17], or Phil Smith’s Mythogeographical “Toolbag of Actions and Notions” ([18], pp. 144–75), these strategies are “there to be given life by their readers”, not as endpoints of our own explorations ([18], p. 9). Ultimately, they are offered as prompts to performative action within the routines and spaces of commuting. In recording and representing such activities, a performative document will emerge that extends our mapping process beyond the scope of this article to engage with other forms and methods of mapping everyday journeys. Alongside the deep map presented here, we continue to gather stories and images of experimental commuting journeys on our website: www.makingroutes.org [2].

Figure 1.

Everyday Commuting Excursions on a Reimagined Journey. Designed by Rachel O’Neill.

Figure 1.

Everyday Commuting Excursions on a Reimagined Journey. Designed by Rachel O’Neill.

2. Performing Striated Space

Our mapping process is influenced by concepts of mobility drawn from nomadic theory: the condition of nomadism; and an attempt to incorporate a nomadic form of mobility into our regular journeys. Drawing on the “nomadology” of Deleuze and Guattari [19], and Rosi Braidotti [20], we aim to document a performative “counterpractice”, learning more about our own commuting routes by considering alternative ways of traveling between two sites, and examining our exiting daily journeys through the lens of these key theorists of contemporary mobilities. Before discussing our own experiences, it will therefore be valuable to consider the potential for, and limitations of, a nomadic form of commuting.

As we have discussed, commuting is often portrayed as a problematically limited, constrained and regulated mobile practice. In contrast, Pearson sees the nomad as an aspirational figure, “cut free of roots, bonds and fixed identities” ([21], p. 20). Nomadism offers a valuable counterpoint to commuting, then, but it is a concept that we are anxious about adopting too readily without confronting some of the potential problems with its use. As Tim Creswell points out, although the metaphor lends itself to an antiessentialist discourse that emphasises “the importance of becoming” over that of destinations, the use of the nomad in Western intellectual thought is essentially “a form of imaginative neo-colonialism” which uses the non-Western other to project romanticised notions of mobility against the sedentary power relations of the State ([22], p. 47, 54). Embracing the concept of the nomad runs the risk of ignoring “who travels and why” ([23], p. 361).

These questions are particularly pertinent to a discussion of commuting, as a mobile practice that is constituted through significant social and economic hierarchies. Gil Viry et al. identify a range of factors that lead to inequality in contemporary commuting practices that is predicated on access to certain forms of mobility. These include not owning a car, residential areas with poor access to public transport, and “weak temporal or organisational resources to handle projects that require travel” ([24], p. 121). These factors contribute to an important shift in the way we acquire and build capital in a mobile world, which John Urry refers to as “network capital” ([25], p. 197). The ability to move (or to choose not to move) now constitutes a “major source of advantage” in a society that relies, more than ever before, on systems and processes of mobility ([25], p. 52).

Deleuze and Guattari’s discussion of nomadic forms of mobility provides a valuable aspirational counterpoint to this heavily systematised, regulated and unequal spaces traversed through commuting. Unlike the “striated” space of roads, ferry routes and trainlines that we use to transport ourselves between work and home, nomad space is smooth, defined by “the variability, the polyvocality of directions” ([19], p. 382). Moving within vast, open spaces such as deserts, tundras and steppes, nomads make paths, moving from point to point through the landscape. However, as opposed to sedentary societies, the points of a nomad journey are “strictly subordinated to the paths they determine”, rather than the other way round ([19], p. 380). Importantly, although commuting does not fit easily within this model, this is not to say that the commute precludes a nomadic relationship with the environment:

Even the most striated city gives rise to smooth spaces […] Movements, speed and slowness, are sometimes enough to reconstruct a smooth space. Of course, smooth spaces are not in themselves liberatory. But the struggle is changed or displaced in them, and life reconstitutes its stakes, confronts new obstacles, invents new places, switches adversaries.([19], p. 500)

Bearing in mind Deleuze and Guattari’s warning that we should “never believe that a smooth space will suffice to save us”, we recognise that our creative explorations of our own commutes are significantly limited in their ability to address the network capital that we require to go “off route”. We are nonetheless setting out on a personal journey to “confront new obstacles” and “reconstitute the stakes” of regular journeys which have occasionally left us feeling “desensitised” to our own bodily experience of the landscapes that we move through. In this way, the example of the nomad offers us a new way of thinking about and experiencing our commutes, rather than reconstituting the systems that contain them and the socio-economic context that we travel within. Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of reconstitution resonates with Braidotti’s concept of nomadism as “a myth, or a political fiction, that allows us to think through and move across established categories and levels of experience” ([20], p. 26). Braidotti advocates “nomadic shifts”; “a performative metaphor that allows for otherwise unlikely encounters and unsuspected sources of interaction, experience and knowledge” ([20], p. 27). In these shifts, our everyday practices are opened up to the creative processes of becoming, offering an “acute awareness of the nonfixity of boundaries” and “the intense desire to go trespassing, transgressing” ([20], p. 66).

Critical appropriations of nomadism have acquired a great deal of currency in postmodern accounts of mobility and it is easy to see how they suit our purpose here. These concepts offer an appealing invitation to the disgruntled daily commuter to leave the striated space of the commute and go “trespassing” and “transgressing”. The details of the specific journey must be taken into account, although the tools we offer can be applied to any commute in an attempt to enact “nomadic shifts”. What mode of transport is employed? Is it public or private? What is the usual pace of this journey? Is the journey open to disruption? Wilkie identifies that discourses of walking practices such as pace, value, autonomy and agency can also be applied to road travel but questions whether “motorvating” actually does open up “previously unavailable opportunities for freedom, escape and subversion” ([16], p. 85) or whether the “democratisation” of road travel has remained mythic for those without network capital.

As pointed out by Janet Wolff, the “suggestion of free and equal mobility is itself a deception, since we don’t all have the same access to the road” ([26], p. 235). As a result, Cresswell has been challenging the “romanticisation of the nomad as the geographic metaphor par excellence: for some time ([22], pp. 42–54); ([23], p. 361). Embracing the metaphor of “generalised heroic figures resisting the confines of a disciplinary society” (itself a specifically postmodern appropriation of a previously vilified cultural figure), is to “gloss over the real differences in power that exist between the theorist and the source domain of the metaphors of mobility” ([23], pp. 378–79). It is important to point out, therefore, that we are not claiming that our creative experiments in the spaces of our daily commutes could be described as nomadic, or indeed that such a thing as nomadic commuting could ever exist, let alone be captured on a map. Rather, we are using “nomadology”, and the creative becoming the myth of the nomad encapsulates, to prompt an alternative way of thinking about quotidian and functional journeys that prioritises creativity and imagination over an assumption of disutility within striated space. We aim to “mobilise metaphors of mobility” by exploring different ways of engaging with the landscapes that we move through between home and work ([22], p. 56). By temporarily departing from our usual modes of transport, we intend to re-perform our own repetitive forms of mobility and reconnect to our regular routes through a series of experimentations with different modes, rhythms and conditions of travel.

3. Mapping Our Commutes

Laura’s commute is made up of four parts. The “rhythms” of her journey between Sandy Beach, where she lives, and her place of work in Glasgow, incorporate a ten minute drive from her house to the ferry terminal in Dunoon, a 25 minute ferry across the Clyde estuary, a 44 minute train journey from Gourock to Glasgow and a ten minute walk up Hope Street from Central Station to the RCS.

David’s 50 minute car journey from Glasgow to Ayr takes him initially through a maze of residential streets, roundabouts and traffic lights to the ramp at the end of the Great Western Road where he joins a short stretch of the M8 south through the city and over the River Clyde to join the M77, which cuts through the Ayrshire countryside before meeting the A77 at Kilmarnock. This is “Route 77”, according to the sign for Balbir’s Restaurant which marks the final stage of his journey, and he has always enjoyed the connection to the great American highway.

We started this project by keeping commuting diaries, documenting the range of activities undertaken during our regular journeys to and from work. Laura kept a notebook record of her journeys every day between September and December 2013:

Tuesday 15th October 20137:00 leave house, 7:15 boat, 7:47 train, 8:45 arrive at work.17:25 train, 18:20 boat, 19:00 arrive home.On both journeys today I read Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost. I like it and a statement in capital letters on the back cover reads ‘NEVER TO GET LOST IS NOT TO LIVE’ [27].Monday 28th October 201316:55 train, 17:50 boat, 18:30 arrive home.I take my suitcase on the train and finish reading the book my Aunt Mo has lent me called Olive Kitteridge. It is falling to bits as she read it on her travels to India. It travelled with me to Manchester but was not read [5].

Reflecting on her diary, Laura observed behaviours that she performs repeatedly; mainly reading and sleeping! She enjoyed noticing how many books had been passed on to her from friends and family, and how the books were on their own journeys through “striated space” of commuter routes, being marked by their journeys and the bodies that facilitated their wanderings.

Meanwhile, limited by his role of driver, David used the hands-free mobile phone device in his car to phone spoken diary entries to himself, which he later transferred to MP3 files and transcribed.

It’s drizzly but the sun is cutting through the clouds and picking out the oranges and browns of the autumn trees. And it makes me think this is so much better than having to commute on an underground train in a busy city. I really value this time to drive through the countryside every day [28].

This process of keeping commuting diaries prompted us to look for ways to open up our journeys and to more meaningfully connect with our commutes and the spaces that we move through. Entries immediately reveal an active and productive use of travel time. However, this is too often a movement that drives “through” landscape, rather than travelling “into” it; and while our modes of transport carry their own particular risks, they generally operate through a comfortable dislocation from our wider environment. Less expensive, and ecologically damaging forms of transport—such as walking and cycling—allow a different type of engagement with commuting routes. While the choice to walk and cycle is significantly determined by levels of network capital, it is also the case that walking and cycling have the potential to be more exciting, pleasurable, interesting and relaxing than other modes of transport, and that the physical dimension of these more basic modes has a range of benefits to the regular commuter [29]. This raised an important question for our project: how could we temporarily shift our commuting practices to other forms of travel that might offer us a more corporeal, visceral and hands-on encounter with our routes? And what “benefits” might we accrue through this process?

There are significant parts of our journeys that more closely resemble Sennett’s version of desensitised travel [6]:

Monday 4th November 20136:30 leave house, 6:45 boat, 8:45 arrive at work.There is a boat refit on from the 4th to the 16th of November so I have to leave my house at 6:30 to get in for 9am. There is a long gap between the boat and the train and the train at this time of the morning is very cold. I read Uncle Silas (on loan from my sister) and doze on the train.Sunday 24th November 201318:00 Western ferry, arrive home 19:00.I drive so cannot do anything with the time [5].

There are also moments when we are prevented from undertaking the necessary journeys. In general, Laura’s journey is much more prone to disruption than David’s due to the modes of transport involved:

Thursday 5th December 2013Both boats are off due to high winds and the road is flooded so I cannot travel to work today. This is the first time this has happened this year and I miss the second year show that I am supposed to be assessing which I am really disappointed about [5].

The commute is often perceived, and experienced, as a boring, stressful and frustrating form of mobility [30] (see Figure 2). However, for Edensor this “everyday realm” of “habit, routine, unreflexive forms of common sense, and rituals […] paradoxically also contains the seeds of resistance and escape from uniformity [through] the intrusions of dreams, involuntary memories, peculiar events, and uncanny sentiments” ([31], pp. 154–55). The etymology of the word “commute” is from the Latin “commutare”, which means “to change, transform, exchange” [32]. We are interested in the potential of this repetitive journey from home to work as creative or transformative. Braidotti claims: “the imagination is not utopian, but rather transformative and inspirational” and we wanted to use this collaborative project as an opportunity to experience these journeys anew, to revise them and re-imagine them” ([20], p. 14). We have found that the experience of being in transit lends itself to such moments of imaginative departure.

Laura Watts and Glenn Lyons account for the imaginative dimension of travel, arguing that movement leads to an “ambiguity of place”, a “liminality” that can foster “a valued sense of creativity, possibility and transition” ([33], p. 109). We set out to disrupt the regular patterns of our commutes and have used the “gift of travel time” to mobilise a critical engagement with our commuting behaviours [9]. This has led us to seek alternative commuting methods, which use different rhythms, physicalities, routes and durations, and opens up our journeys to riskier, messier forms of mobility. Where we usually travel by car, ferry or train, we therefore set out to discover what walking, cycling, swimming and boating might teach us about our journeys to work.

Figure 2.

The road to Glasgow.

Figure 2.

The road to Glasgow.

Four key concepts define the theoretical landscape through which we travelled. However, as our experiences have shown, there are no clear boundaries here. We are moving through heterogeneous and multiple spaces, and routes interweave, blur into each other and amalgamate. These concepts offer us a structure, then, but should not be understood as discrete, fixed categories: first, convergences and divergences of paths and routes and their relationship to the boundaries and barriers that contain and define them; second, notions of becoming, changing and transferring; third, patterns and rhythms of commuting and ways of documenting and analysing these processes; and fourth, the corporeality of commuting as an embodied practice. Together, these concepts offered us an analytical framework for our exploratory journeys, and a set of “guidelines” for the process of recording and representing these journeys, and we paid careful attention to these aspects of our alternative commutes. They provide a loose structure for the map that is beginning to emerge. In the remainder of this article, we present a textual and photographic “deep map” of our walked journeys, followed by individual representations of swimming (Laura), cycling (David), and boating (Laura). This is followed by a brief discussion of the postcard project conducted by Laura on the Gourock to Dunoon ferry route, in order to open up our personal experiments to consider, and learn from, other people’s experiences of commuting (see Figure 3). We conclude the article with our suggested “strategies for performing the daily commute” in the hope that others will take up our invitation and map their reimagined regular journeys.

Figure 3.

Deep mapping display at the Lighthouse, Glasgow.

Figure 3.

Deep mapping display at the Lighthouse, Glasgow.

4. Walking (Laura Bissell (LB) and David Overend (DO)

For Braidotti, “nomadic subjectivity” is an opportunity “to identify lines of flight, that is to say, a creative alternative space of becoming that would fall not between the mobile/immobile, but within both of these categories” ([20], p. 7). This linking of “lines of flight” with “a creative, alternative space of becoming” offered us a valuable starting point and in March 2014, we both set out to walk our commutes. David walked 48 miles in three days from his home in Glasgow to the University of the West of Scotland in Ayr. A few days later, after a ferry journey from her home on the Cowal Peninsula, Laura walked 27 miles to the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in Glasgow over the course of one day. Ostensibly, our commutes close down lines of flight to fixed paths across “striated” landscapes [19]. These walks aspired to the opposite—open routes through smooth spaces. What follows is an account of the beginning of our research journeys made up partially from our written responses and critical reflections on our reimagined commutes.

Shortly after leaving his flat, David followed a path along the River Kelvin. In his written account of the walk, he reflects on the way in which our routes through cities often follow fixed paths:

I [...] realise how much of the city is cut up and divided by fixed routes and paths. This grid of different boundaries and trajectories comprises bridges, footpaths, cycle lanes, roads, railways, canals and flight paths [...] But as I walk from point to point, following some routes and crossing others, I do not feel hemmed in or constrained. There is a freedom in this journey and an exhilarating sense of moving beyond the prescribed uses of urban space [34].

For both of us, undertaking our journeys independently, we enjoyed this sensation of transgression or resistance. As Deirdre Heddon points out, walking allows a potentially “resistant” engagement with landscape—resistance “to habit, to capitalism, to rules, to expectations” (and, suggests Smith, “to fashion”) ([18], p. 198); [35], p. 104). Our diaries reveal numerous occasions when we moved against the habits, rules and expectations of our commutes (see Figure 4). We also observed the “resistant” behaviour of other commuters. For example, Laura recounts a moment when a fellow pedestrian breaks out of a designated route:

as I am about to walk around the cordoned section to allow me to move towards Gourock, the woman in front of me undoes the catch on one of the metal gates, opens it and walks through [...] I follow her lead, glad of this minor transgression of the authoritative paths and designated walkways that the area by the water assigns [36].

Figure 4.

Fences mark the boundaries of prohibited areas on both walked routes.

Figure 4.

Fences mark the boundaries of prohibited areas on both walked routes.

We are wary about the claims that can be made for such activities and want to avoid what Doreen Massey dismisses as “the least politically convincing of situationist capers” ([37], p. 46). However, these moments of quotidian transgression offered many important formative experiences during our walks, many of which involved a rupture or break in an established pattern or rhythm that we have previously felt frustratingly locked into. Employing Braidotti’s “myth” of the nomadic subject to “[blur] boundaries without burning bridges” ([20], p. 26), these moments of transgression during our walks allowed us to reimagine our commutes as something other than functional and transitory journeys through the spaces between home and work.

Braidotti’s focus on process and “becoming nomad” is analogous to looking for a marker on a road or path: “the nomadic subject is not a utopian concept, but more like a road sign” ([20], p. 14). For much of Laura’s early route, particularly in the Argyll and Inverclyde stages, the road signs are supplemented by another with the Gaelic version of the town name. Often there are four signs which read as a list: district, town, PLEASE DRIVE CAREFULLY, and the Gaelic version (see Figure 5). Laura notices that a large number of the signs also have stickers on them, added by people. Signs are objects that invite us to look at them for information or guidance, but these have been augmented by the public, creating an alternative meaning to that which was intended. What the signs are signifying is also in a state of becoming; the meaning malleable and open to interpretation, obliteration, and subversion.

Figure 5.

Road signs for Greenock on Laura’s walked route.

Figure 5.

Road signs for Greenock on Laura’s walked route.

These signs served as regular route-markers and they established a rhythm to these walks—marking progress by miles walked and hours passed. However, because “all spaces are dynamic and continually pulse with a multitude of co-existing rhythms and flows”, some rhythms became more apparent than others ([12], p. 200). During his walk, David reflected on the rhythms of his regular journey by car:

In my car, the rhythm of the road takes precedence as my ‘insulated mobile body’ remains oblivious to everything else ([12], p. 200), but this walk allows me to seek out, sense and immerse myself in multiple rhythms including weather, seasons, animals and people who use and inhabit the landscape that the road cuts through. As I approach Symington, there is a brief moment when I can see the A77, the Firth of Clyde and a Ryanair plane taking off from Prestwick—rhythms and flows coexisting [34].

Earlier in his walk, crossing Eaglesham Moor, the rhythms of Whitelee Windfarm create a unique relationship between technology and landscape (see Figure 6):

We surrender to the hypnotic quality of the turbines, which offer a regularity and rhythm approximating the effect of music. Our ambulatory rhythms sync up with the rotations of the blades and we adjust our pace accordingly. One foot after the other meets one rotation after the other. At the same time, in this exposed location, rain beats into our bodies and blasts our faces with icy water. The wind is blowing in tremendous gusts, which drown out all other noises, but in the occasional dip, our ears tune into another constant sound—the faint, humming drone of the windfarm [34].

Figure 6.

The turbines of Whitelee Windfarm.

Figure 6.

The turbines of Whitelee Windfarm.

Edensor points out that commuting takes place within “routinised, synchronic rhythms [which] are bureaucratically regulated and collectively produced” ([12], p. 196). In the systematised rhythms of motorways and shipping lanes, these natural rhythms—of weather seasons, animals and people—can easily be obscured. For Henri Lefebvre [38], the establishment and regulation of rhythms is one of the key ways by which late capitalism produces and controls space. Similarly, Deleuze and Guattari identify “the function of the sedentary road, which is to parcel out a closed space to people, assigning each person a share and regulating the communication between shares” ([19], p. 380). By attempting to establish a “nomadic trajectory” we aspire towards the opposite: movement within what Deleuze and Guattari refer to as “an open space” ([19], p. 380) and the potential to take up Edensor’s project of “tailor[ing our] journeys in accordance with [our] own strategies, imperatives and feelings” ([12], p. 196). However, this was not always as easy as we hoped. As David reached the southern boundary of the golf course at Pollock Park, his route was blocked by a high metal fence:

My dilemma is whether to add more miles to my journey by trailing the perimeter looking for an exit, or to attempt to cross into the adjoining field. The solution presents itself as I notice a missing railing which I suspect has been removed deliberately to open up a walking route. I make my way through woodland and clamber over another lower fence and land in squelchy mud. Following the high wire fencing that separates the field from the M77, I enjoy a feeling of subversion and recall Braidotti’s vision of nomadism as ‘the intense desire to go trespassing’ ([20], p. 66). Whether or not this is strictly trespassing, it is a moment that embodies the spirit of this journey, moving against prescribed uses of space and reimagining my route as a space of creativity and transgression. However, just as I cast myself as the heroic psychogeographer, I come face to face with a large highland cow. Its menacing stare, sharp horns and slow, deliberate movement towards me make me nervous and I look around for an exit route in case things turn nasty. Unfortunately, I am now too far from my entry point to retreat, and the section of fence that I am beside is too high to easily climb over. The cow lunges forward and a surge of adrenaline catapults me over the fence before I have time to think. On my way over, I scratch my shin and slightly cut my finger. Writing up my notes almost exactly a week later, the cut is still faintly visible - a corporeal document of this encounter [34].

These moments of pushing, testing or breaking the body punctuated our walks, which were defined by physical endurance as much as situationist escapism. Opening up the possibility of corporeal intrusion into our commutes provided an alternative to Sennett’s passive commuter bodies [6]. Over the following months, we took this part of our investigations a step further as David cycled to work, and Laura considered ways to negotiate the Clyde Estuary.

5. Swimming (LB)

The 27-mile walk I did in March 2014 had been a very enjoyable experience: the day was sunny and warm and I took great pleasure in noticing elements of my journey that the usual pace does not allow. “Walking is pedestrian” as Smith says and despite the blisters at the end of the longest day of walking I have ever done, I was aware that it was just walking ([39], p. 14). Most people can journey by foot and walk from A to B and I had not undertaken any specific training for my epic day of walking from dawn till dusk. The sea-swim, however, was a different story and the sense of anticipation and fear around undertaking this physical challenge seemed to grow as my various attempts at swimming from Gourock to Dunoon (across the Clyde Estuary where my ferry crosses) were usurped. Initially I had hoped to complete the swim prior to David’s and my visit to Lapland in April for a mobile train conference [40], however freezing temperatures and rough seas at this time of year made this impossible. I intended to swim the Clyde on the 28 June as part of an organised sea-swim and had ventured out in my wetsuit for some trial swims with my dad rowing alongside me in his dinghy in case I encountered difficulty. After training in the local pool, my first sea-swim was a pleasant surprise. The water was a reasonable temperature, there was nothing awful floating by and I tried very hard not to think of what might be happening in the deep black murk below. One day I even had a friendly seal swimming alongside me and the sense of pervading dread I had felt since I decided to do the swim began to recede. Every day since I made the decision to swim the ferry journey I had looked slightly differently at the body of water I crossed on the boat each morning and evening, assessing the waves, the tides, and what I might be sharing the water with. One week before the event I ended up in hospital with a soft tissue infection in my leg and made the decision not to do the organised swim. Disappointed and immobile I asked my dad to accompany me later in the summer in his boat so I could complete the task I had set myself.

As the warm summer weather dwindled there was one weekend left at the end of August which would be suitable and the 23 August was decided as the date for my next (and final) attempt. The morning was calm and I travelled to my parent’s house at 8:00 a.m. to set off in my dad’s boat from the West Bay to the Cloch lighthouse on the other side of the estuary. I think my family had hoped that by the end of the summer my will to do the swim would have waned and my dad had seemed anxious about the journey in the days prior to it. When we launched from the West Bay to motor the boat across, almost immediately we lost a small part of the outboard motor in the water. I stripped to my wetsuit and dived into the freezing sea to try to retrieve it but to no avail. This sobering start meant that we had to try to find another part for the motor but after several attempts we realised that it was not going to work and my dad began the process of rowing us across the sea. What I did not realise at the time was that in one of the attempts to start the outboard motor my dad had staved his middle finger but he did not tell me this as we embarked upon our slow transition across the estuary, nor would he let me row so I did not exert myself before the swim. Due to our slow and calamitous start we did not reach the far side and the Cloch lighthouse where I had intended to start but with this in near sight, I lowered my already soggy wet-suited body back into the water to begin the swim back to land. I filmed part of this swim using a camera attached to my head, but, like David’s experience of filming when cycling (see below), the film is skewed, a sideways shot of the blue sky peppered with fluffy clouds with a triangular sliver of sea sloping across one side of the screen. The occasional shot of my dad in his dinghy comes into view as I turn to speak to him as we assure each other we are alright. Although the swim was tiring and I subsequently caught a chill (probably from having to dive into the water sooner than intended and then sit in a damp wetsuit while we rowed out) I remember thinking as I was doing it how much I love being in the sea. The buoyancy of your body that the salt water provides makes for an exhilarating feeling of floating. At times I felt as though I had to really push my fins into the sea in order to propel myself forward as they felt as though they were continually floating upwards towards the blue sky as though seeking air. Back at shore, the relief was palpable, no one had died in the attempt (as my sister had feared) and although we did not make it from point A to point B as intended, I felt as though I had swam enough of the journey to justify having done it. Afterwards, I thought about my dad. I had not realised how stressful my attempt at doing this would be for him. Watching the video back I think about his finger and how he did not tell me about it because he did not want to disappoint me in not being able to complete the journey I was so eager to do. I also reflected on how rarely in these re-imaginings have the start and end points (and journeys in between) been exactly the same as the commute that I do every day. Perhaps a re-imagining is also a re-inventing, a re-creating of these journeys and their purposes and meaning (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Laura in Dunoon after her seaswim.

Figure 7.

Laura in Dunoon after her seaswim.

6. Cycling (DO)

According to the old maxim, “it’s just like riding a bike”, the skill of cycling, once learned, is never forgotten. As I had not cycled for many years, I reassured myself with this thought as I set off on 11 May 2014 from Glasgow to Ayr on a borrowed old mountain bike with a Go-Pro camera fixed to the handle bar. As it turns out, cycling is not at all like riding a bike. I nervously manoeuvred my way through Finnieston and across the River Clyde, brakes squealing and wheels wobbling. At some point in the first few minutes, unnoticed by me, a jolt knocked the camera out of position and for most of the rest of the journey only my anxious face can be seen, framed by the overcast sky (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

David during his commute by bicycle.

Figure 8.

David during his commute by bicycle.

Before long, the bike and I fell into our stride. I corrected the camera angle, breathed in the cold spring air and propelled myself forward into the route. Sometime later, just north of Moscow (yes, there is an Ayrshire village called Moscow!) hail stones the size of grapes began to shoot from the sky as the weather turned savage—reddening my exposed legs and soaking me in freezing rainwater. I searched in vain for a shelter and eventually found an old barn where I sheltered for a few minutes. As I waited I realised that the muddy ground was swarming with insects crawling out of the deluge into the safety of the manmade structure. I weighed one discomfort against the other and decided to plough on through the downpour (I could hardly get any wetter).

Cycling occupies the middle ground between walking and driving: fast enough to feel a tangible sense of progress at any given moment; but slow enough to feel a corporeal connection to the landscape. I remember this journey vividly a year later. The exhilaration of the wind in my face as I sped downhill along country lanes, the mud splattering all over me, and the chilling soaking as I approached Ayr. As an extremely irregular cyclist, I do not have a sense of cycling as a mode of commuting, which can be perceived as just as “forgettable, ordinary, banal” as my commute by car ([41], p. 291). This experience, for me, was like Phil Ian Jones’ artistic experiments in route-marking by bike, and allowed me to engage with this form of mobility as “sweaty, visceral, emotionally intense and highly embodied” ([41], p. 291). When I arrived at my hotel later that afternoon, it was one of the most warming and relaxing moments of arrival that I have experienced. This is a welcome return from the détournement of the journey, and it reminds me of Smith’s observation that “the permanent drift disappears the drifter” ([18], p. 139). Returns, homecomings and finishing lines. Unlike nomadic journeys, all these exploratory commutes have an intended endpoint.

7. Boating (LB)

In the Victorian era when Glasgow was the “second city” and the tobacco merchants were making their fortunes, the local seaside town of Dunoon grew as the wealthy merchants built holiday homes within sailing distance of the city. Dunoon became a popular holiday resort and steam-powered boats transported thousands of holiday makers “doon the watter” of the river Clyde into the Firth of Clyde for summer holidays and Glasgow fair weekend. This continued until the 1960s when a controversial American naval base was built in the nearby Holy Loch and the rise of cheap package holidays to warmer climes meant that the popularity of Dunoon as a holiday destination declined. My grandparents met at in Dunoon on a Glasgow fair weekend and my father spent a lot of his childhood holidaying in Dunoon and subsequently my sister and I spent many rainy summer holidays following suit. My parents moved to Dunoon six years ago and I moved to the nearby village of Innellan the year after. The faded elegance of Dunoon as a popular Victorian resort and the history of the town includes a shift from sea travel to alternative means. The Waverley is the world’s last sea-going paddle steamer and epitomises a mode of transport that was once the norm but is now all but obsolete. Almost my entire commute can be done over water and so I wanted to travel by boat from Glasgow through the narrow banks of the Clyde river in the city centre as it opens out into the Clyde Estuary and out to sea.

I undertook my usual commute by car, ferry and train to get to Glasgow on the morning of 22 August, one of the Waverley’s last sailings of the summer season. Boarding the boat at Glasgow’s Science Centre (the recent addition of new bridges over the city centre stretch of the Clyde makes this the closest point that larger vessels can travel to and from) the boat is busy with day-trippers heading to various seaside resorts (the steamer will stop at Kilcreggan, Dunoon, and Rothesay). There is something very alluring about the Waverley’s design and over all three levels of the steamer there are details of design and engineering that are notable. In the midsection of the boat is the engine room where the mechanics and workings of the engine are on display. The large paddle can be seen moving through the water through the portholes at each side of the boat.

The journey “doon the watter” is very pleasant. I stay on the port side of the boat so I can film the commute I do every day from the perspective of the water (see Figure 9). I am pleased to notice familiar landmarks from my walk and the shift from the scrapyards and building yards of the city into the yellow fields of Inchinnan is beautiful. Once almost at Greenock I move about the boat and film various parts of my journey around the steamer. We stop at Kilcreggan, a small village near Helensburgh, before journeying on to Dunoon. I think how lovely the pier looks as we approach the town and also think about how on my daily journey I do not look at this anymore, or do not see it in the way I once did. The experience of being on a “daytrip” on the Waverley allows me to see Dunoon as a visitor might on arrival. The antiquated mode of journeying has also made me think about Dunoon’s transition from holiday town to declining working town and I wonder if the tourists who visit Dunoon on the Waverley transport the destination back to a former identity—a seaside town visited for pleasure during the summer holidays as I experience it on this day. It was this experience that encouraged my “everyday commuting excursions” postcard project with designer Rachel O'Neill, where we wanted to use some of the nostalgic aesthetic that often appears in connection with the golden age of steam travel to ask contemporary boat travellers to reimagine and map their journeys and to see the spaces between home and work a-new.

Figure 9.

The Waverley.

Figure 9.

The Waverley.

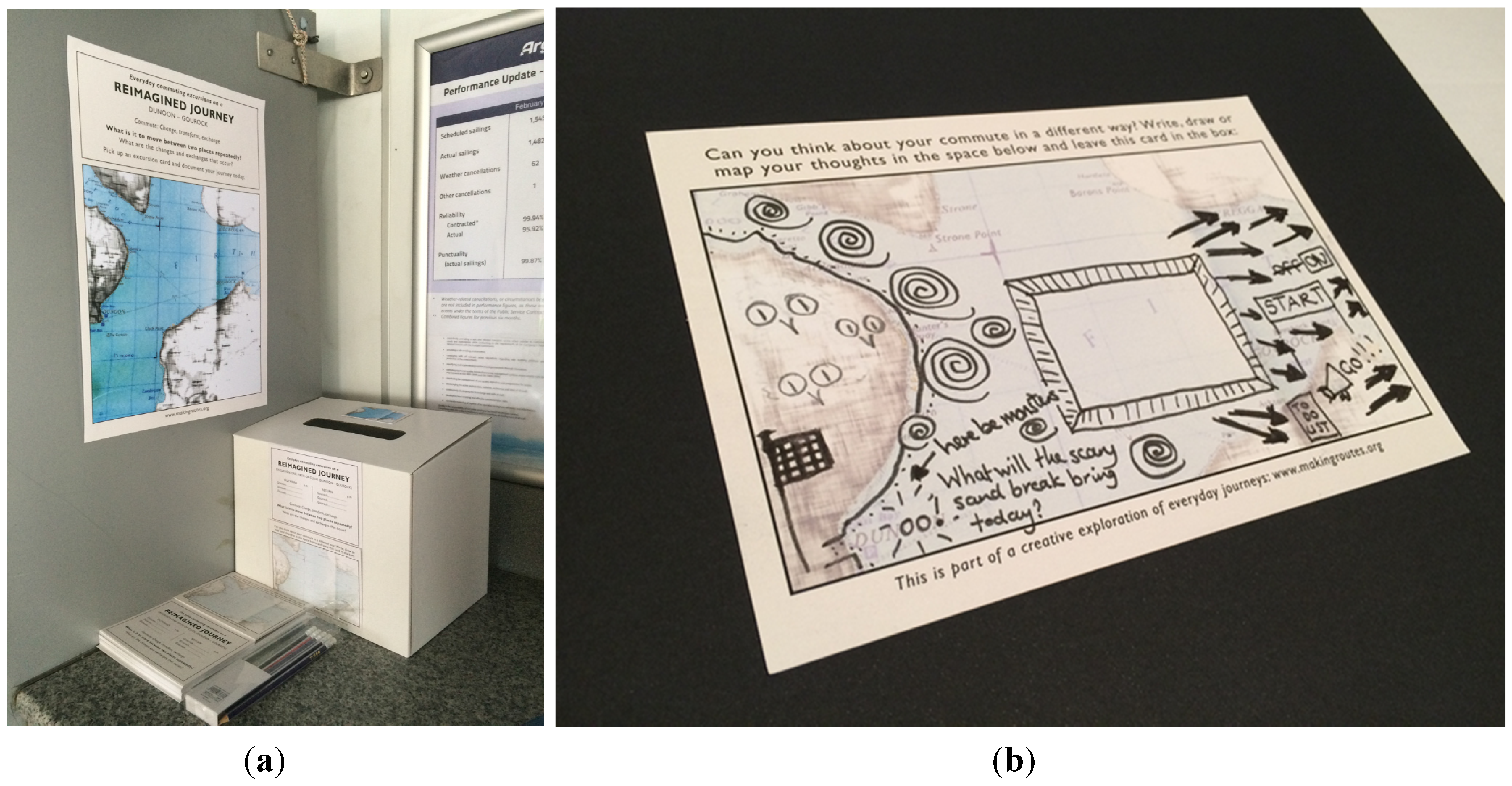

8. Everyday Commuting Excursions

One of our mapping experiments, which Laura developed with O’Neill, was a set of posters and postcards encouraging commuters on the Gourock to Dunoon ferry to reimagine their everyday journeys as “excursions”. When Laura traveled down the Firth of Clyde on the Waverly Steamer in August 2014, she acknowledged that the arrival at Dunoon ferry terminal by steamer as opposed to ferry made her see the Victorian pier and the town beyond differently. By traveling on a historic mode of transport the feeling of being on an “excursion” as a “daytripper” rather than a commuter encouraged a “seeing a-new” of the familiar site. Inspired by this and by the nostalgic posters portraying the golden age of steam travel on the Clyde situated within the newly developed Gourock train station, Laura wanted to engage other commuters in a creative act of mapping that would encourage them to reimagine their everyday journey by boat and to “see a-new” the space between home and work. The design of the materials was influenced by ferry brochures and posters from the 1950s and commuters were asked to offer a creative response to a map showing the area travelled over water between the two ferry terminals. By obscuring the landmass and emphasising the sea using colour and detailed markings, the design was intended to ask people to consider what this space and time travelling over water could be. Participants mapped, drew or wrote in the space provided on the postcard to offer an alternative mapping of the spaces between home and work and posted it into a postbox on the Argyll Flyer ferry (see Figure 10). These responses were collated into a book which was displayed at the Lighthouse in Glasgow in July and the maps completed by members of the public can now be found on the Making Routes website [2].

Figure 10.

(a) Postcards at the Gourock ferry terminal; (b) One of the public responses.

Figure 10.

(a) Postcards at the Gourock ferry terminal; (b) One of the public responses.

The responses of the public were varied with some participants drawing feelings they had about their journey and others offering practical solutions for the “problem” of the journey. One postcard depicted an arm with a floating balloon attached over Dunoon and a ball and chain on an ankle for Gourock implying a feeling of lightness and freedom when “home” and a heaviness and responsibility connected with the “work” side of the map. Some of the contributions conveyed the history of the area with one showing a “map of memories of Clyde piers” with sketches of now defunct or absent piers as boat travel has become less popular. Others used the postcard to convey the social aspect of the journey with one participant writing: “The boat is a place to meet friends old and new” and another explaining it was a time to “exchange knowledge of local community events”. Some simply drew crosses on the map to depict the journey and one childlike drawing of a boat on the map was also offered. Practical solutions to some of the problems of travel also featured with some offering suggestions of a walkway between the two points and the simple statement “UNDER 18 GO FREE”, which hints at some of the issues young people face in Dunoon with many of the colleges situated over the water in Greenock. By asking commuters on the Dunoon to Gourock ferry to reimagine their journey as we had been doing with our respective commutes we were able to share our ideas with a specific commuting community. Encouraging people to share their “maps” (both literal and imaginative) also gave us an insight into how our strategies or prompts might also offer us new ways of thinking about our routes.

9. Strategies for Performance

As we attempted to reimagine our commutes, the overarching aims of the journeys and routes remained consistent but the pace, rhythm and embodied experience and exertion varied greatly depending on the mode of travel or transport. The answers to the questions “where have you come from?” and “where are you going?” were always the same, and always interchangeable (either “home” and/or “work”) for every journey we undertook. Within this “formula” for these journeys we began to think of our experiments as strategies or variables for this predictable and repetitive commuting route. By varying the method by which we filled the space and time between “home” and “work” we were able to challenge our own understanding of these quotidian and functional journeys. Our walking, swimming and boating journeys introduced a range of approaches to mobility that allowed us to depart from our established rhythms and routes and reconsider the liminal transitory space between the fixed sites of “home” and “work”. The start and end points remained (roughly) the same, however the journeys themselves offered a space of possibility—of becoming—that differed for each reimagining. Furthermore, what started out as a relatively discursive and academic exploration of commuting—an attempt to apply a nomadic thought experiment to our regular journeys—soon became far more physically and emotionally affective than we had originally considered. Our deep map contains accounts of venturing out into woods, estuaries and country lanes, often inexperienced and underprepared for a range of hostile and challenging environments and modes of transport. This introduced unpredictability, risk and endurance as key elements of our journeys. This aspect of our experiments in commuting will benefit from further research, and opens up potential routes for ongoing work in this area. In this final section, we distil some of these experiences into a list of “strategies”, which are offered for others to take up our project of “performing the daily commute”. If these strategies lead to a greater degree of uncertainty, and lead those who undertake them into challenging situations, this is all for the better. However, be careful out there.

- (1)

- Alter the pace of your commute to take from dawn until dusk, or for a full weekend, week, month or year

- (2)

- Perform your commute in the hours of darkness

- (3)

- Undertake your commute on an obsolete/historic mode of transport

- (4)

- Spend the night at your place of work and commute in the opposite direction as you travel home the following morning

- (5)

- Take your friends and family with you

- (6)

- Create a guided tour for your route

- (7)

- Leave extra time for unplanned detours and unexpected encounters

- (8)

- Plan an alternative route and take this every day for a week

- (9)

- Research the history of your route and re-enact previous travellers’ experiences

- (10)

- Record every human exchange along the way—every nod, wave and conversation

For those who are tempted to employ these strategies, or to invent new ones, we encourage the sharing of experiences and images on the Making Routes website [2]. As this project continues to develop, this site will extend this mapping project to maintain the deep map as an open, dynamic and multi-layered document, rather than fixing any “findings” in this journal article. Nonetheless, our process so far allows us to draw some initial conclusions.

10. Conclusions

On the first day of his walk, David cheated and briefly broke the task of his continuous journey on foot, returning by taxi to his home rather than spending the night in a soulless budget hotel. The following morning, returning as a car passenger to resume the walk where he left off, he noted that he was “already thinking of [his] commute differently, pointing out places he walked through the day before and noticing features of the route of which [he] had previously been unaware” [34]. Similarly, Laura noted her aspiration that the walk would allow her to “re-experience my commute in an active and embodied way” in order to “emancipate” herself from what Braidotti refers to as “the inertia of everyday routines” [36]. Our experiments in commuting have shown potential in this respect as both of us feel that applying our various performative experiments to our commutes, has changed the way we experience our daily journeys in several important ways. The postcard project “everyday commuting excursions” also allowed us to encourage commuters on the Dunoon to Gourock ferry to creatively map their thoughts and to reflect on these routine journeys and what the space between home and work means to them.

First, although we continue to follow the same roads, railways and ferry routes, we no longer feel as limited by, or contained within, these prescribed patterns. We have developed the appetite and tools to go “off route”. In this sense, we have inserted “nomadic shifts” into our regular journeys [20]. While the sites of “home” and “work” remain fixed, by applying the first strategy to “alter the pace of your commute to take from dawn until dusk, or for a full weekend, week, month or year” the time and space in between these places has been opened up to the possibility of a deeper engagement with the landscapes we previously (and continually) traversed at great speed.

Second, Braidotti’s insights into nomadism as a way of reimagining subjectivity have allowed us to consider the commute in terms of “becoming” [20]. The change in time and space as we travel these repetitive routes provides a liminal space for commuters to be always changing through new encounters and experiments, even when regularity and repetition are the dominant modes of engagement with a particular route. The sense of departing, moving, traveling and arriving all indicate moving in, through and out of places and the transitory and fluid sense of fixed time and space allow for a space of creative imagining. Strategy three: “undertake your commute on an obsolete/historic mode of transport” can assist in this exploration of time and space, as can strategy nine: “research the history of your route and re-enact previous travellers’ experiences”. All of the “findings” from these exploratory journeys deepen the historical and geographical range of the map.

Third, we have encountered multiple rhythms that are co-present with our commutes, whether synchronously or asynchronously. Our walking, cycling, swimming and boating journeys have offered us an opportunity to encounter this rhythmic multiplicity beyond those elements that are foregrounded during our regular commutes. The physical exertions of our alternative commutes have allowed for an understanding of the rhythms of the body in relation to the landscape we have moved through depending on how we travelled. We have attempted to capture this rhythmic variety through our mapping process, moving from anecdotal to academic registers and shifting our mode of documentation as we travel.

Fourth, we have engaged in our commutes in a more embodied way and pushed ourselves beyond the ostensibly passive bodily experience of commuting. Smith says “the walk can bring you and your body into new connections through its aches, blisters, shivering and sweating, dehydration in intense heat, dizziness, pain, exhaustion, alienation” ([39], p. 62). David’s exhaustion and painful legs from cycling allowed him a new appreciation of rest and shelter, while Laura’s fear of whether she would physically be able to complete the sea swim and this challenge moved her beyond her perceived bodily capabilities. These journeys have helped us develop an understanding of a more overtly corporeal engagement with the space of our commutes. We had the cuts, bruises and blisters to prove it—a form of deep map temporarily etched into our bodies.

As we continue our research in this area, we will find new ways to reimagine and map our regular journeys, as we aspire to become (more) nomadic commuters. We are going to keep journeying together and hope to explore the potential of the repetition of our journeys over a much longer period of time. What is it for a body to move between two places repeatedly? What is the “change” or “becoming” within the body through this process? By deep mapping our commutes we have learned more about the places we move through, our personal narratives and perspectives on our travels and how our experience and memory provides a sense of seeing anew the journeys we do every day. The idea of “mapping” has been literally explored through Laura’s experiments on the ferry where she asked people to “map” their journey while undertaking the boat journey from Dunoon to Gourock, but the framework of “deep mapping” has allowed us to conceptually map our journeys through a series of embodied alternative experiences opening up the possibility of transgression and reimagining. The challenge for us now is to keep the map open and evolving in order to maintain a sense of our commutes as spaces of becoming, and to continue to reimagine what our journeys are and the potential of what they could be.

Author Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Laura Bissell, and David Overend. “Rhythmic Routes: Developing a Nomadic Physical Practice for the Daily Commute [keynote paper].” Scottish Journal of Performance 2 (2014): 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Making Routes.” Available online: www.makingroutes.org (accessed on 5 April 2015).

- The Arches. “Making Routes Launch Afternoon.” 2011. Available online: www.thearches.co.uk/events/arts/arches-live-2011-the-arches-and-the-university-of-the-west-of-scotland (accessed on 2 February 2015).

- David Overend. “David Overend is Misguided in Ayr.” 2012. Available online: makingroutes.ning.com/profiles/blogs/david-overend-is-misguided-in-ayr (accessed on 2 July 2014).

- Laura Bissell. “Commuting Diary.” Unpublished manuscript. 2013–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Sennett. Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization. London: W. W. Norton, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jean Baudrillard. The System of Objects. London: Verso Books, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Michel de Certeau. The Practice of Everyday Life. London: University of California Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Juliet Jain, and Glenn Lyons. “The Gift of Travel Time.” The Journal of Transport Geography 16 (2008): 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricia L. Mokhtarian. “Travel as a Desired End, Not Just a Means.” Transportation Research Part A 39 (2005): 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony Elliott, and John Urry. Mobile Lives. Oxon: Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tim Edensor. “Commuter: Mobility rhythm and commuting.” In Geographies of Mobilities: Practices, Spaces, Subjects. Surrey: Ashgate, 2011, pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Mike Pearson. “In Comes I”: Performance, Memory and Landscape. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mike Pearson, and Michael Shanks. Theatre/Archaeology. London and New York: Routledge, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fiona Wilkie. “Site-Specific Performance and the Mobility Turn.” Contemporary Theatre Review 22 (2012): 203–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiona Wilkie. Performance, Transport and Mobility: Making Passage. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carl Lavery. “Teaching Performance Studies: 25 instructions for performance in cities.” Studies in Theatre and Performance 25 (2005): 234–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phil Smith. Mythogeograhy. Axminster: Triarchy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles Deleuze, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. London: The Athlone Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosi Braidotti. Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory, 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mike Pearson. Site-Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tim Cresswell. On the Move. London: Routledge, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tim Cresswell. “Imagining the nomad: Mobility and the postmodern primitive.” In Space & Scoial Theory: Interpreting Modernity and Postmodernity. Edited by Georges Benko and Ulf Strohmayer. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997, pp. 360–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Viry, Vincent Kaufmann, and Eric Widmer. “Social Integration Faced with Commuting: More Widespead and Less Dense Support Networks.” In Mobilities and Inequality. Edited by Timo Ohnmacht, Hanja Maksim and Max Bergman. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2009, pp. 121–44. [Google Scholar]

- John Urry. Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Janet Wolff. “On the Road Again: Metaphors of travel in cultural criticism.” Cultural Studies 7 (1992): 224–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecca Solnit. A Field Guide to Getting Lost. Edinburgh: Cannongate Books, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- David Overend. “Commuting Diary.” Unpublished manuscript. 2013–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Birgitta Gatersleben, and David Uzzell. “Affective Appraisals of the Daily Commute.” Environment and Behaviour 39 (2007): 416–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleanor Mann, and Charles Abraham. “The Role of Affect in UK Commuters’ Travel Mode Choices: an interpretative phenomenological analysis.” British Journal of Psychology 97 (2006): 155–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tim Edensor. “Defamiliarizing the Mundane Roadscape.” Space and Culture 6 (2003): 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Dictionaries. “Commute: Definition of commute.” 1999. Available online: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/commute (accessed on 28 March 2014).

- Laura Watts, and Glenn Lyons. “Travel Remedy Kit: Interventions into train lines and passenger times.” In Mobile Methods. Edited by Monika Büscher, John Urry and Katian Witchger. Oxon: Routledge, 2011, pp. 104–18. [Google Scholar]

- David Overend. “David Overend Walks Route 77.” 2014. Available online: makingroutes.ning.com/profiles/blogs/david-overend-walks-route-77 (accessed on 31 March 2014).

- Deirdre Heddon. Autobiography and Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Laura Bissell. “Walking Gourock to Glasgow: Reimagining my Commute.” 2014. Available online: makingroutes.ning.com/profiles/blogs/walking-gourock-to-glasgow-reimagining-my-commute (accessed on 11 April 2014).

- Doreen Massey. For Space. London: SAGE, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Henri Lefebvre. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Phil Smith. On Walking. Devon: Triarchy Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Laura Bissell, and David Overend. “Reflections on a Mobile Train Conference from Helsinki to Rovaniemi.” Cultural Geographies in Practice. Published electronically 19 February 2015. [CrossRef]

- Phil I. Jones. “Performing Sustainable Transport: An artistic RIDE across the city.” Cultural Geographies in Practice 21 (2014): 287–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1An early version of this article was presented as a keynote paper at the British Sociological Association Regional Postgraduate Event at Glasgow Caledonian University, UK, 13 June 2014 [1].

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).