2. Results

For this paper I have taken this unresolved shifting in the privileging of different parts of the entanglements of mythogeography and used that motion as an uneasy theoretical basis for an interpretation of the two sets of photographs taken during two ‘walks with objects’. These walks were separated by a gap of almost four years, the first on April 27, 2013 and the second on January 10, 2017. On both walks the same tactic was deployed: to walk without a destination, and to be guided by whatever objects the walker/s were drawn to and, where possible, to carry the objects with them, allowing the objects to inform the walk as they were carried along, and for the walker/s to interact with them, until the walker/s were drawn to a new object when they would pick that up and leave the carried object in its place. Repeating until the walk was felt to be completed.

The first walk, in 2013, I took alone, and began in Torbay Road in the seaside town of Paignton (Devon, UK); on a strip of cafes, takeaways (one selling startlingly orange chips), tattoo parlours and gift shops geared to serving holidaymakers. It would lead me down to the beach, then I would go southwards along the front, cutting back and inland until finally returning to the first beach. From the beginning, when I photographed the castle-like shadows (

Figure 1) thrown in a broad alley, I seemed drawn to objects that I could interpret in some way. My attention is on everyday signage about prices or goods combining with unlikely representations—like the statues of Ancient Egyptian gods at Neffy’s Coffee House and in the doorway of a casino—invoking an absurd and unlikely authority. The sign for Misfits tattoo parlour declares “BLESSED ARE THE WEIRD PEOPLE: The Poets, THE ARTIST... the Writers & MUSIC MAKERS, the Dreamers & Outsiders”, and yet its cultural appropriation of Chinese imagery, Union Jack over its doorway, and the pirate symbol on its window all denote varieties of conformity. The YOU THINK IT WE PRINT IT! clothing shop displays (presumably) attractively exemplary images for t shirts (

Figure 2); they are mostly ubiquitously marketed nationalist, motor vehicle, superhero and music fan symbols. There is very little sense in my early photographs of active subjectivities at work (including my own); nor of any agentive materiality. Instead, the things represented in the images seem driven and categorised by symbolism; my choice of images by the ironies at play.

The one image that breaks this pattern came as I looked closely at the statue of a gorilla (

Figure 3) outside one of the cafes, noticing how the material was responding to people rubbing its hands and feet, polishing those parts of the object with grease and salt from their own hands. I was drawn to the evidence of

where this attention was directed. Perhaps down to small children touching parts of the statue most available to them, or perhaps the opportunity to enact an impossible interaction with a giant animal; intimate and gentle, and far from the reaction intended by the formative symbolic portrayals of male gorillas like Emmanuel Frémiet’s 1887 sculpture or the King Kong movies: of animals disposed to rape.

Crossing an emptied, tarmac-surfaced space, from which it appeared that either play equipment or a carousel might have been removed, there was a cast iron gate at one end spelling FUNLAND.

I headed for the beach, where I began to pick up and dance with various objects: sticks, shells and seaweed. I see from the photographs that I switch from using a knife-shaped stick, adding to my own shadow on the sand—an image of aggression that I remember feeling uneasy with—to waving a piece of seaweed in relation to the horizon (

Figure 4a,b). The sharp knife-like stick had pulled my focus downwards, to the sand, but the seaweed had drawn me to the distance and these are the last images taken on this beach.

Crabbing off the beach and around the harbour, nothing ‘grabbed’ me until I found a flower bed of red earth and reached down to lift out a coagulated lump of the soil. Looking at the photograph now, I am struck by how the focus is on a red-painted anchor in the background—a part of which I had touched and cupped with my hand, perhaps unconsciously mimicking (I have no memory of noticing the connection at the time) those who had felt parts of the metal gorilla sculpture. My preoccupation seems to be with the context from which the objects have come, rather than with the objects themselves. I had taken a token of the soil (

Figure 5a), a part of the ‘whole’—reproducing mythogeography’s disposition to moving directly from ‘small’ things to a ‘big picture’—just as I had waved the seaweed in relation to the sea vista.

I walked with the red soil, coloured by the same 300 million year old Permian deserts as had stained the beaches; iron oxidising as 400 million year old Devonian limestone mountains cracked and crumbled under the impact of millions of years of sun and storms. I broke the lump of soil as I went; my own personal anthropocene. I photographed the gently cupping hand, but the fingers were grinding as I walked. Taking the soil to the next beach—Goodrington Sands—playing with the meaning of the walk with the help of the red soil seemed ironical; as if a seam stitched the touch of the sand in my hand—changing, as changed, from gritty to silky—and the give of the sand under my feet, wet and dry; I read the sand and the sand read me (

Figure 5b–e). When I held the dry earth over the waters, I was playing with the two objects, soil and sea, as the parts of a metaphor, and as parts of a constructed image (foreground and background).

The sudden appearance at the back of the beach of a steam locomotive (

Figure 6), apparently racing along the roofs of the candy-coloured beach huts, seems to have shocked me discomfortingly into a different scale. While the objects I had chosen to play with, crumble, toss and shake, were easily manipulated in my hand—and my hand had, through the lens of my camera (set to automatic) become a distinct “player” in my walk, apparently somewhat independent and agentive in its own right—the locomotive was of a quite different ‘order’, capable of crushing or amputating that hand, obliterating its structure and identifiableness. I could block the engine’s appearance—as I could the sun from my eyes, by raising my hand—but the HRUFFF HRUFFF HRUMPH of its expulsions of smoke, the hot furnace of the boiler that I knew would be roaring as it ‘got up steam’, and the hauntological clank of its joints—would still impose upon me. The train’s massive and spectacular consumption of fossil fuel returned me briefly to the role of a spectator in the world; to carbon, to being a resource of production rather than a producer. I was jerked out of the pleasant, sunny, easy setting oneself ‘at the mercy’ of the objects in the welcoming terrain of a holiday beach; riding the thinned out and secularised ambience of threadbare leisure had generated a melancholy pleasure. But the giant (scale, again, was important, but I am not sure I noticed so at the time) thing was not even ‘real’—it was a nostalgia-object, a massive marker of what had gone, but, evidently, had not gone itself. Absence marked by what remains. A private railway.

The viewing carriage at the end of the train was like a metaphor tacked on to a machine. The large glass windows made passengers and onlookers alike into spectators of each other, divided by a hard transparency. I was hugely pleased with the pictorial look of the thing; but I was implicated in something which made me feel uneasy.

I don’t remember whether it was that steam locomotive which turned me inland; or if the “motive” in its name struck me then as it does now when I strike keys to type it on the screen in front of me.

There are no photographs until I reached some kind of green enclave, a small nature reserve, a distance (some hundreds of metres) from the shore. I have, despite numerous visits, and study of maps and Google images, been unable to find my way back to this green space within the town. Wherever I look and however I map it, there does not seem to be space for it. Yet, I have the images of the faded paint and lichen crusted signboards at its boundary. The framing of the images show that I am enjoying dismembering the sentences: “VALUE”, “REMAINS” (

Figure 7a,b). Changing meaning by isolating and re-juxtaposing words. The formality and moralism of the exhortation to respect and value over, or rather than, enjoy entangles with what is, for me now, the objective elusiveness of the place itself. I cannot find the it of it. The détourned moralism of the images entangles with something in me that cannot re-find the signs and itself in the same space.

The photographs show trampled paths, the shadow of the bushes and trees, and the exchange of the last few crumbs of soil for a stick (

Figure 8a) and then the exchange of the stick for a plastic top from (I think) a cylinder of Pringles crisps (

Figure 8c). My tossing the stick (

Figure 8b) and then skimming the plastic lid into the blue sky; trying and failing in the case of the lid to create a blurry image like that from a UFO sighting.

These images provoke little in the way of affect or imaginary orientation. While I have some sense of how my body felt on the beach and—without looking at a map—what my route had been, I have very little sense of how I was or of exactly where I was and where or how I went within the nature reserve (I first mis-typed “reverse”) of that “was”. These images no longer seem to attach themselves to any memories. Perhaps because memories are recreated each time they are called-to-mind, rather than simply accessed from a fix store of recall, my failure to re-find the ‘actual’ space has perhaps neutralised or short-circuited the affect of the memory. I can recall the shape and shadows and colours; but I don’t feel them in the memory any more. I ‘know’ that there was a certain ‘magic’ to the space and I assume there was some nervousness as I made my way down dark and narrow paths between tall green shrubs and ferns (but were there ferns?), yet I don’t feel that, or the memory of that, now.

Only when I get to the photograph of the steel container—I remember this being on the very edge of the green space, transitioning to a new kind of terrain, a void space between the nature reserve and an institutional building of some kind—do I once again remember feeling the presence of an object and how it actively marked a change of ambience, which, in looking at the photos of it, I somehow ‘re-feel’. I have at some point used the facility on my pc to turn the image of the container upside down so that the word “SKY” can be read ‘right-way-up’ and the image of the sky is inverted. The image of the sky becomes unreal—“SKY” rather than sky is the real thing—the sky falls to the ground (

Figure 9a). And, I do remember how on the day its giant blueness was as close and dominant as what was holding me up from beneath. The space of flying as thick as the space of falling; which perhaps explains my evident desire to throw things in the air and photograph them in flight.

Having failed in the attempt to make a fuzzy but coherent ‘UFO’ image, I used the Pringles top to ‘attach’ to the contrail of an airliner passing overhead (

Figure 9b). I am unsure if a memory of the sound of its engines has been obliterated, or if in the moment, by making a nonsense of the distance, I had obliterated a perception of it, or if there was none to be had. It is odd to look at an image and

feel its silence, particularly; given that all the images are silent.

Rather than cupping, whirling, stabbing, crumbling and wiping, I was now tossing and skimming and holding up.

Once beyond the green space and the boundary zone marked by the steel container, I do remember the look and feel of a road, Fisher Street, in which I stood and held up the plastic lid against the blue sky. I felt a tinge of ‘alienation’ there, an a-sitedness, a struggle to ground myself with the tall brick walls and thatched roofs, and the suburban-style houses, a sense of exclusion and anonymity that I had not felt in the town up until then; an uneasy and defensive space on the edge of the town’s centre that had not yet relaxed into a suburb, but was no longer ‘important’ or central to what the town now was.

Perhaps that is why I was so thrilled—I recall the rising excitement the closer I looked—by the decaying palimpsest (

Figure 10) at MABEL PLACE (MARLL CLOSE). It was, though, still stuck in a messing with representation. The feel of warm dry earth and of twisting and turning my body on the beach in response to seaweed and the sharp stick were gone now; my sense of the lostness of the street, unable to connect what it had been to what it is was, now entangled with my own sense of inappropriateness and out-of-body-ness. Yet, I couldn’t then—as far as I remember—and have not since worked out the proportions of that unease. I walked the street again recently, as part of a different project, and felt an echo of that experience, a connection to my imagining of what it was rather than to the feeling in-itself. Maybe that is why I wanted to throw the UFO from it, drag the airplane down to it. Play the silly word game about it.

At the junction of this street with a busier, arterial road, I called in at a ‘junk shop’, attracted by the display of items on the pavement outside. Surreptitiously depositing my plastic lid on one of its shelves, I bought for a few pounds (I forget the exact prices, but the total may have been as low as £2) a silhouette print and an oil painting of a seashore (

Figure 11), both framed. Rather than take grime from the gutter or some dropped litter, I was returning to my initial focus on representations (and now increasingly sophisticated ones) instead of things-in-themselves.

I brought my two purchases out of the shop and laid them out in order to view them in the sunlight (

Figure 12). The painting depicted a seaside scene and a cloudy sky; yet the sunlight that was directly bearing down that day, in the image, seems to spiral in the texture of the paint itself; a substitute sun for the one ‘missing’ from the painting. The reflection is the thing itself and, at the same time, the representation of itself; rather than simply acting (in the everyday sense), the sun was performing (in the theatrical sense). I remember the intensity of the sun that day, but the feeling of the memory, the affect that the recreated memory (each time I recall it now) generates, is not as intense as my immediate experience of the photographic image now, as I type this: I sweat a little as I sit at the computer; my forehead is sticky. The stickiness on my fingers, which I transfer to the keys as I type this, feels related to the texture of the oil paint of the framed picture, softening, back then, under the sun. So, while the materials are no longer accessible—the painting long ago disposed of—there is the effect of that softening, that agency. There is a sense, then, in which the experience, the memories and affect of memories, all run into each other, in the way that the colours of a painting might do the same if they remained under intense heat, and that what replaces the sun and paint as agents is the act itself: the softening. Something that had been lacking in the direct ‘setting oneself at the mercy of’ the terrain and its objects on the day of the walk, was now compensated for in my tainted engagement with their representations, not by the symbols or the re-presenting of the objects, but by that softening which continues to have agency upon materials (in this case, upon the bodily, physical materials—the skin and its perspiration—of affect).

The text in German for the silhouette I had bought was “Ein Strāußchem am Hute und den Stab in der Hand”—flowers in the hat, and a stick in the hand—the title of a German song of ‘wandering’, the practice of a solo male figure who abandons home, driven by the attractions of rootlessness, abandoning the “lovely girl” he meets because he feels compelled always to return to his search for the “far country”. This might sound like an uncompromising indictment and abandonment of domesticity and belonging, but the melancholy “wandersmann” can be read another way: as an indictment of what belonging and home (and homeland) have become. That home, love and country were only—at least, at present—available in ideal terms. The melancholy of the “wandersmann”, who eventually walks beyond his own life onto celestial trails and looks back through his grave to how little he has enjoyed of earthly happiness, fits with a reactionary, but modernist ambience, a belief in the “decline of the West”, in a European cultural ennui in the face of industrialism and foreign exoticism. It is no surprise then that the figure of the wanderer, escaping the cities for the rural or wild path, would be fought over by fascists and socialists alike in the 1920s and 1930s (the artist responsible for the silhouette I had bought, Richard Borrmeister, chose his own path, painting propaganda postcards for the Nazis in the 1930s).

Given that many of my research and performance practices are focused on modes of walking, it appears odd, in retrospect, that I hardly engaged with this print at all; photographing the text and artist’s name for my record, but apparently uninterested in its depiction of a walker. Compared to the two images taken of this print, I took a further 25 photographs of the painting, which I carried to the beach—a knowing obviousness: ‘a painting of a beach, where else should it go?’—and using it as a base for an assemblage of items found at the water’s edge, finally setting it ‘at the mercy’ of the gently incoming waves.

First, however, the images show that I had wiped, in small circles, some of the grime from the surface of the painting (

Figure 13), allowing ‘balls’ of the brighter blue and white of the painted sky to come through the otherwise dirty surface; seeing these images I am fairly certain that I was referencing the aerial phenomena sighted over Nuremberg in 1561 and the contemporary woodcut of the event by Hans Glaser (

Figure 14).

Yet, although the reference seems apparent to me now, I had entirely forgotten making any such marks at all, until I saw the images again, let alone there being any resonance with a second German printmaker. My memory is excitedly focused, apparently to the exclusion of other actions, on the brightly coloured assemblages and the play of light on the water within which I set the painting of the beach (

Figure 15a–d).

Conducting this remote auto-ethnography of my walks for this article, enacting a kind of Passivity-as-Research, in which I mull over images, I have struggled with the sheer number of items that make up the assemblage of visual materials; there is far more than I can hope to address in the writing here. Volume, silence and distance are all active.

Using my camera as a notebook precluded the punctuation of my journeys by repeated jottings in a notebook. I have no reason—which does not mean there are not any—to believe that written note-taking would have been any more reliable a means to recover the walks. When I am note-taking, either during or immediately after a walk, I am aware that there is always a layering involved, with a varying thickness/thinness of description. That no matter how immersed or immediately reflective these writings may be, they are always already mediated. The reviewing, copying and pasting and describing of images for this article, has not felt to be instrumentally or emotionally very different from the lifting and quoting of passages and phrases from a set of notes. Sitting at the pc, the objects I see represented on the screen no longer have an apparent agency of their own—the pc is, at my request, performing their re-presentation. Their digital images, however, do have some agency: they sometimes resist their use by their non-readability, too blurred or dazzling, sometimes the software reads the camera’s original orientation and they swivel through 90 degrees when inserted in the text. My own manipulations of these images—juxtaposition, shrinking, and so on—while assembling the paper, mostly writing in between the images, rather than writing the text and then illustrating it, as I usually do, are poor relations, affect-wise, to my engagement with the objects encountered on the walks; the objects are always absent. Even if I had archived all the objects I walked with, their agencies—drying out, crumbling, slipping behind piles of papers—would have been quite different. A small, and immediate instance of this took place on the first walk: after it was ‘over’, walking back to the station with the oil painting, part of the thin card backing suddenly fell away (

Figure 16a) to reveal a hilly landscape painted on the reverse of the beach scene, with a text (that I found impossible to decipher) written in blue ink on the inner part of the card (

Figure 16b).

I miss the pleasure of the walking, I remember it with pleasure; however, in trawling through these images—there are so many of them that I begin to feel lost even though I am mostly able to ‘place’ where I found and left these things—I am anxious; I feel out of control at times, daunted by an obligation to explain. Much of the imagery feels beyond my ever-understanding. Yet, in the walk, even when I had perceived a bewildering complexity of textures or materials or juxtapositions, I still seemed to find a way of being enjoyably at ease with them. Writing with the images at my pc, I am enjoying what I have produced (the incremental completion of the task), but when walking I was enjoying the becoming that the walking was ushering. On the walk I was both in the present, in the moment and engaging with the absurdity of that: everything around me marked by its contingency and genealogies. Sifting through the images, however, I feel that I have over-de-familiarised both the things and myself; that the verfremdungseffekt is too strong. Rather than a disruption of an overly taken-for-granted process revealing its mechanics, I am brusquely alienated (and alienating) from the machine of myself. Expecting to write about the affect of the walks through the inadequate resources of a photographic gallery, the taint of auto-ethnography—rather than a tainted auto-ethnography—turns out to be the more powerful. The problem is more primary and fundamental than I had expected: the appropriating impulse in relation to things on an exploratory walk, and the melancholic and gendered affect of the exploratory walker in relation to an imagined passive and ever-forgiving landscape, have been just as much present (to be deferred and resisted) in a process of writing from images as in a process of immersed note-taking.

Indeed, one dynamic that has emerged from the review, here, of the images of the first walk is the disappearance, or ‘falling off’ of the landscape from the edges of the images. That in enacting an intensifying focus on the ‘close to hand’, searching down through layers of the terrain as advocated by Tim Ingold, cited above, the danger was not so much of an evaporation of the materiality of things, a reduction of what they do to what they mean, but, rather, an exaggeration of their discreteness. I had acted out, as if programmatically, the idea of the real thing as non-relational; a concept central to the ‘Object-Oriented Ontology’ of Graham Harman and others; a particular quality captured by Jean-Luc Nancy as “the sleeping thing at rest, sheltered from knowledge, techniques, arts of all kinds, exempt from judgements and prospects” (

Nancy 2009, p. 14). The tramped dirt of the paths, the furniture of the shop and the sand on the beach had been gradually squeezed out of sight. Although I had attempted to maintain some dynamic by my assemblage of objects on the painted canvas, the effect is less of a collective meaning and more of their fierce and colourful independence as discrete things: dead crab, tennis ball, cuttlefish bone.

Working against this forward impetus to discreteness, that has emerged in the writing here, has been a more synchronic process of comparison. I had drawn from mythogeography’s privileging of the multiplicity of narratives, cited above, with the effect of putting something of a pre-emptive torque on too sudden a rush to the linear unfolding of the walks as their most significant quality. Rather than review first the images for one walk and then the images for the other, I have moved back and forward between the two collections. Similarly, with my written analysis. In my head, this movement feels geographical as much as it is intellectual. The two walks took place in comparable spaces, on the same stretch of coastline, both including beaches and a seaside town. It did not feel as if I were moving far in order to make speculative comparisons, so where there are differences, they feel more like significant variations within similar materials than the disparities of unlike things. I was as likely to detect variations within one of the walks as between the two.

So, for example, I detected that between the first two photographs taken on the second walk, this time with my daughter, Rachel, there is a shift. Although the subject of the images is largely the same, I seem to have taken a second image (

Figure 17b) in order to put the object in sharp focus rather than my daughter’s hands, which were the subject of the camera’s focus in the first image (

Figure 17a).

We had begun our walk in January 2017 at the railway platform at Dawlish Warren, an assemblage of holiday camps with fixed housing units, caravans and mobile homes. From there, we crossed the fringes of a nature reserve onto the dunes, and to the concrete promenade above the beach. Some way back within the dunes, we had passed a complete razor shell—without the razor fish—which may have been collected and dropped by a person, or by a bird (

Figure 18).

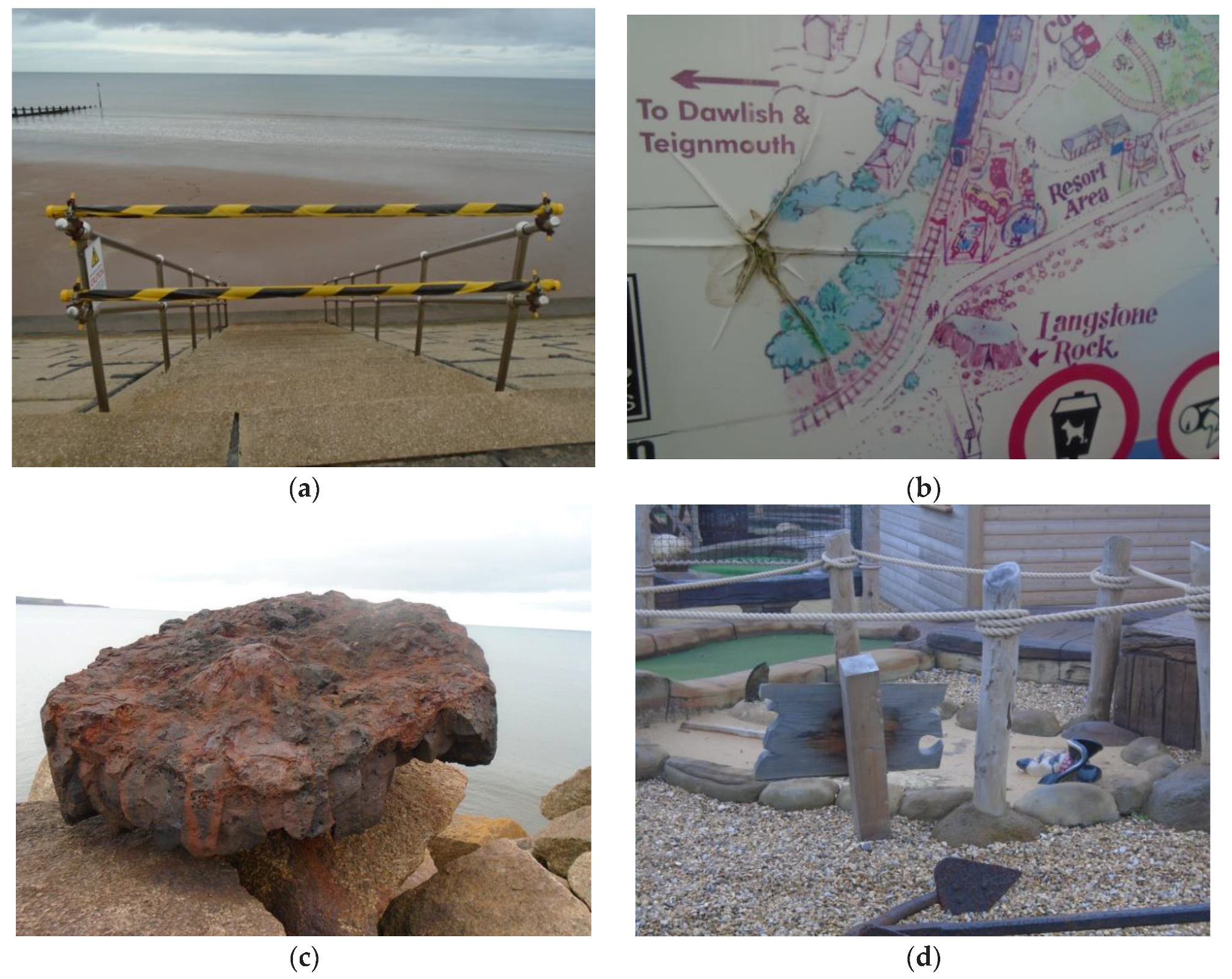

In the images that followed, there are images of objects being held or moved or animated by human bodies, as in the images from the first walk; but what is different is how many of the images are of objects—whether of human production or not—that are without any kind of human manipulation in the image (

Figure 19a–d).

Our presence is far less felt, than mine is in images from the first walk. The images of the objects themselves suggest their agency; the concrete of a giant and anatomically incorrect skull on a crazy golf course is cracking, rotting and falling away to reveal its infrastructure. A metal table is rusting into pieces (

Figure 20a).

A wind torn Union Jack (

Figure 20b) flaps above the Red Rock Cafe; a piece of which has broken off and is caught in a patch of prickly teazles between the footpath and the railway track where it vibrates in the breeze, shaking in the draught of a passing train. Its colours are slightly faded and the proportions of colouring are suggestive of a French tricolour, or of commercial packaging. The flapping shreds of the flag flying above us may be more coherent and recognisable, but the effect is more abject. We had kept our distance, and were kept at a distance; by fences and the tall flag pole. The images record a recent past, yet it is not that, but the greater sense of agency in the images, that feels as though it requires the present rather than the past tense.

However, I will switch tenses now; to avoid making too brash a distinction between the two sets of images and the two walks. Just as the ‘grounds’ of the two walks felt similar, so their intensity and agency are not at opposite extremes, but are variations along a continuum of similarity.

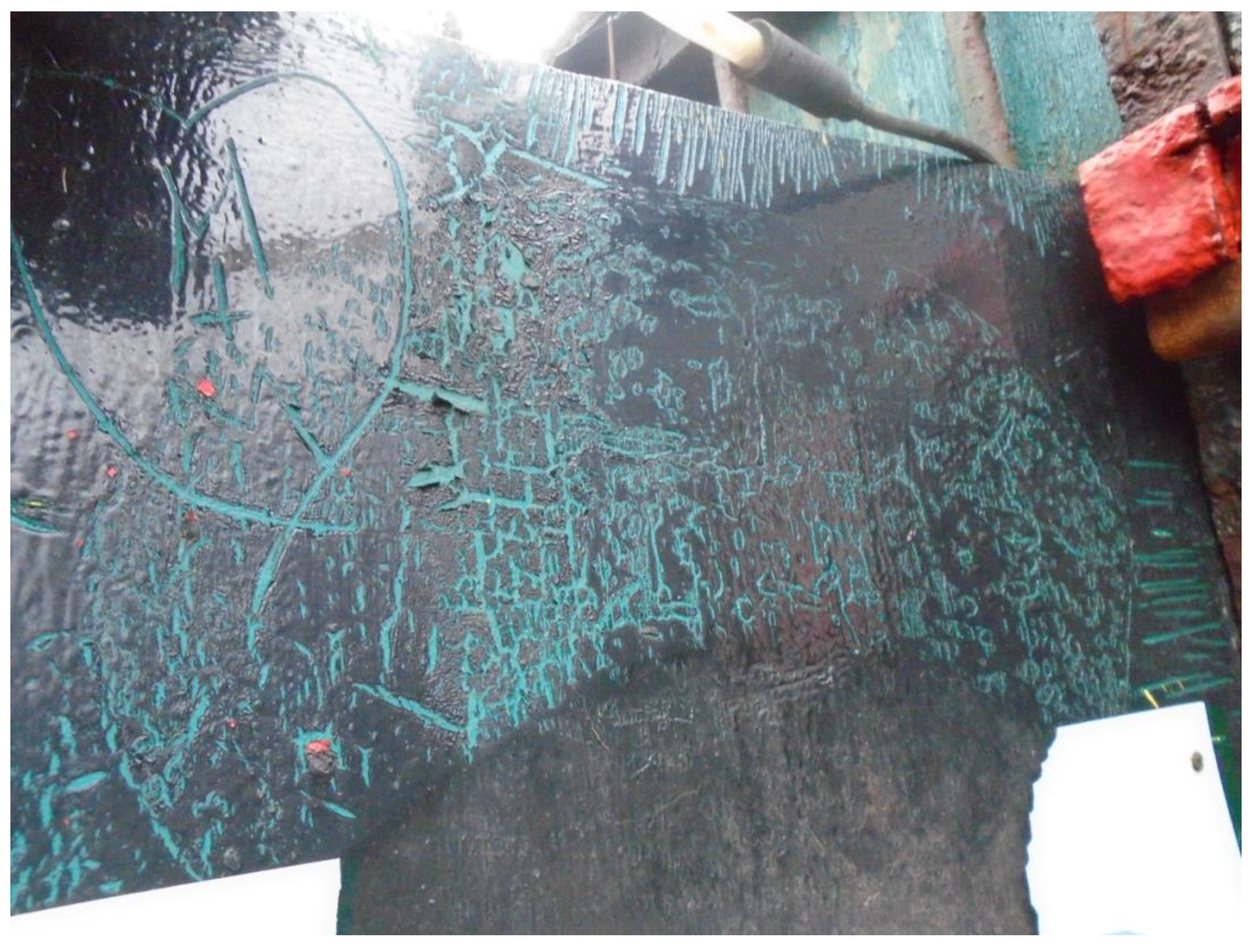

At the top of a door at the back of the Red Rock Cafe, the perishing of black paint (revealing a green undercoat), presumably as a result of the desiccation of materials by sunlight (

Figure 21), was as pronounced as the human scoring of a heart shape; the two agencies were literally entangled.

We climbed on to the ‘Red Rock’ (Langstone Point) beside the cafe; it has no fences, just sheer drops. Even in the centre of its grassy interior, well back from the edges, we felt the vertiginous pull of the drop. While I had previously tended to think of Langstone Rock as a part of the general cliff landscape of this part of the coast, standing at the centre of the top of it, for the first time, that day, it had felt like an independent object; as if I felt the capacity of it as a real object—from the point of view of Graham Harman’s articulation of ‘Object-Oriented Ontology’—to differ discretely from other objects without vanishing thereby into a miasma of descriptive sub-strata. Instead, this affect was more like the “indirect access” that Harman describes as working by “gravitational effects on the internal content of knowledge” (

Harman 2012, p. 17).

Looking at the images with the hindsight of a few months, it strikes me that we had been gazing down on the piece of rail track (

Figure 22) that had been washed away by giant waves during the storm of 2014.

I struggled to safely get back down the steep and muddy path from the top of the Point. Water erosion had washed away two of the wooden steps and it was with difficulty that I levered myself against the damp red walls of the incline and down the gap. I was at the edge of what I was physically capable of.

The mud on my hand (

Figure 23) was an unintended collection (contrasting distinctly with the control I had had over the dry red soil—cupping and crushing—in my hand in images from the first walk). As I struggled to hold onto the side of the muddy cleft, to prevent myself from falling disastrously, the strange configuration of the gulch-like climb and the absence of hand holds was stretching the materials of my body which complained in the joints in my hips and shoulders.

There was a kind of co-operation, evident now in the images. Perhaps triggered by a greater respect for the agency of the giant object of the Point. I am pictured carrying a charred piece of wood with protruding rusty screws (

Figure 24a), then placing it in the sea, to make shapes with and in the foam (

Figure 24b).

The images suggest that we were increasingly interpreting things.

In one photograph, Rachel is ‘modelling’ the basic geology of the area, carrying the two primary local rocks—Permian Red Sandstone and Devonian Limestone—one in each hand (

Figure 25). Then, from what at first seemed like a rock we found strengthening strands of plastic extruding where the composite had been eroded by the sea (

Figure 26a,b).

This was an inversion of the phenomenon we had found back in the car park near the nature reserve at the start of our walk. What appeared to be a filter from a motor had tiny ‘blooms’ of fungi growing on it (

Figure 26c); organic life from commercial product.

The images, at this point, then lose any real suggestion of their objects’ agency as we seem to be less interested in the materiality of what is around us than in what meanings we can construct by manipulating the objects or displaying them in particular ways to ourselves.

On the sea wall we found a series of yellow paint splashes that I was keen to narrate as jellyfish shaped. After which we walked with a greenish stone picked up not far from Langstone Point; without picking up any new objects we walked about a mile. This greenish stone was eventually exchanged for a new object; having carriedit along the repaired sea wall, and well into the seaside town of Dawlish, Rachel placed it on a splash of green paint on the pavement and picked up a dry brown oak leaf (

Figure 27a). Almost immediately we found an ornately carved representation of oak leaves (

Figure 27b) in the frontage of a house, perpetuating the narrative of objects’ meanings realised in juxtapositions rather than by their discrete agencies.

We wandered through an intense blizzard of symbolic objects in the town. The way that the everyday sat side by side with the uncanny and the morbid, defusing each other, seems symptomatic of a barely visually-literate grasping for ill-considered and unvalued meanings and effects (

Figure 28a–f).

Re-orienting ourselves to our new disorientation—how we had been making meanings from juxtapositions was now unmade for us by juxtapositions—which now challenged our easily slipping into a complacent interpretation of things, prepared us for a back street where we found these discontinuities had been concentrated; indicative that such volatile meanings are maybe better understood as energies rather than anomalies, as active in themselves rather any absence or incompetence on the part of human ordering.

In an abandoned hardware store (

Figure 29), the neglect and loss of human order, the subtraction of usual agencies, had heightened the display of some commodities (

Figure 30a,b).

But there was discrete agency too. Through one window we could make out what remained of a display of house letters and numbers. The desiccation of one of the pieces of packaging had released a letter B to fall and settle on the window sill below.

I am familiar with the town of Dawlish, but walking around the outside of the former hardware store building, to the window where the letters were displayed, I found that I was at the end of a lane I did not recognise, with a Spiritualist Church, a house called PIXIES CORNER, a waist-high gate to a three metre sheer drop into a courtyard, and at the other end a White Hart pub. Here, the traditional symbol of the chained white stag with a golden crown for its collar (the badge of the fourteenth century monarch, King Richard II) was juxtaposed with a model of a chained white (or cream) Labrador dog seated inside the pub (

Figure 31).

It was tempting to go inside and ask for some explanation as to why a model of a dog (or was it a taxidermist’s mounting of a real dog’s skin?) should be displayed; perhaps significantly, we chose not to, but allowed the mirroring of the chains to satisfy us.

Despite the excitement of the abandoned hardware store, of which I took 20 photographs, far more than at any other point on our walk, juxtaposition had quickly returned to our walk. When, repeating the rough shape of my solo walk four years earlier, we looped back to end our walk on the beach—via a plethora of odd symbols and objects (a poster for a comedy called ‘Waiting For Gateau’, a cage full of plastic ducks, a sign warning bathers of episodic agricultural pollution of the sea from the stream that runs through the town, sandbags from recent flooding, a hotel with porthole windows and a serious display (

Figure 32) about The Battle of Little Bighorn at Geronimo’s Station Diner—“the stealing of the black hills and sacred lands”)—and there we found what seemed like a curious piece of woody seaweed (

Figure 33). Possibly the holdfast for kelp, or it may have been some kind of seed, possibly of a Raphia Palm tree, or of a Cabbage Palm, or maybe a ‘nymphaea rhizome’ from water lily, floating in on ocean currents from Africa or Central America, or from some local garden. It was not unlike the rear part of the nymph phase of a May-fly. Here was a traveller, almost certainly; a commodity of the colonial and post-colonial trade in plants, perhaps, a hitch-hiker of global oceanic systems, probably, a roamer around identities, for sure. From the main body of the seed or abdomen were protruding (or which was pushing out from itself) strands similar to the reinforcing plastic strands we had found earlier and further northwards up the coast. The inversion was inverted, and we had reinforced our interpretative strategy of doubleness, even while engaging with (breaking apart to examine) a discrete (and probably) plant organism.

Our walk had been complicated by symbolism and interpretation, but the photographs suggest a different level of engagement to that of my first walk; more respectful to the materials and less inclined immediately to narrate juxtaposition or to find meanings in combinations (although this reasserted itself for much of the second half of our walk); instead, at least during the first part, we deferred our own agency and allowed more space for the things themselves to perform their coming to be.

This deferral may account for the insights that were afforded, later, about the dynamic between materials, narratives and symbols, revealingly uncomfortable and unresolved, at work in the town of Dawlish; a raw finding that deserves further investigation.