1. Of Cameos and Memes

For almost two centuries Jane Austen’s works have been igniting popular culture, while in the past few decades the number of screen adaptations, sequels, prequels, or rewritings of her novels has increased impressively. The plasticity of Austen’s texts—her enduring power, that is, to fascinate both academics as well as popular readers, adapt to the trends and needs of each age, and take on a variety of forms—is evident in numerous and diverse adaptations and appropriations of her work, from Hollywood blockbusters to YouTube vlog series, board or video games. Moreover, the young generation of digital natives has discovered a fresh incentive in Austen, as her characters and their modern screen adaptations have taken centre stage in the new media. In the rising meme culture, more specifically, Austen’s views on love and marriage have become an inexhaustible source of inspiration in the exploration of more contemporary concerns, like dominant femininities and masculinities, rape culture, consent, non-conformist desires and sexualities, the male gaze, etc. Jane Austen memes indeed came to claim a noteworthy section in this new cult, as they are being unremittingly disseminated, ‘liked’, ‘re-blogged’, and/or ‘shared’ in platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, and Twitter.

Web 2.0, also known as Social Web, is an evolved variation of first-generation Web 1.0; it encourages active participation on behalf of its users, who are no more restricted to being passive receivers of the content of internet pages, but are given the opportunity to comment on what they read and create content themselves. In this new participatory culture, fostered by social networking sites, image or video sharing sites, blogs, wikis, etc., memes have been rapidly gaining ground and have already become an indispensable part of the digital sphere. When British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term ‘meme’ in his 1976 work

The Selfish Gene (

Dawkins 2006), he defined it as the cultural equivalent of gene, transmitting cultural information through written or oral speech, rituals, habits, fashion, common practices, etc. Like genes, memes evolve through the processes of variation, mutation, competition, and inheritance, and depend on endurance, fecundity, and fidelity. They replicate and transfer data through humans, and, of course, change over time, since humans are never perfect copiers. As a result, some survive longer, whereas others become extinct, depending on whether they increase or shorten the longevity of their hosts, or may lie dormant for years. What Dawkins could not have predicted in the 1970s, however, was the hype about internet memes, a concept that appeared in the mid-1990s, or ‘the meme’s evolution from a simple stand-alone artifact to that of a full-fledged genre’ (

Wiggins 2019, p. 39). Contemporary theorists argue that memes ‘epitomize the very essence’ of our ‘hyper-mimetic era’, and are employed as ‘a prism for understanding [certain aspects of] contemporary culture’ (

Shiffman 2014, pp. 6, 15); more importantly, as Bradley E. Wiggins contends in his recent work on

The Discursive Power of Memes in Digital Culture, memes embody a discursive potential. Perceived as ‘a new form of art’ (

Wiggins 2019, p. xvi), memes are an essential means of commenting on contemporary life and even expressing ideological trends.

What renders memes—a still unexplored area in Austen studies—a distinctly interesting mode of adapting Austen is their size and wit. Given their smallness—memes are most often pictures accompanied by a caption—Austen memes may be studied as modern cameos, those ‘little bit[s] (two inches wide) of ivory’ on which Austen worked ‘with so fine a brush’ and which ‘produc[ed] little effect after much labour’, as she herself puts it in the famous letter to her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh (

Le Faye 1995, p. 146). Furthermore, as witty cultural replicators, memes are constructed on the basis of intertextuality, and (anomalous) juxtaposition, and as mini adaptations, may spoof the original, re-contextualize it, or re-appropriate it.

1 Austen memes are, in other words, miniature doses of irony, this quintessential tongue-in-cheek element in her writing, which ‘joins contradictory truths in search of a new truth that is born with a laughter or smile’, as Anne Hathaway, who plays Jane Austen in Julian

Jarrold’s (

2007) biographical film

Becoming Jane, declares.

In light of the memes’ capacity to enable new readings of texts past and present, and given Austen’s popularity in this fast spreading cult, our aim in this essay is twofold: first, to examine the writer’s proximity to this new genre, as traced in Northanger Abbey, a novel that relies on a hands-on readership and a genre founded on self-parody; and second, to explore ways in which these contemporary cameo artefacts, which borrow from Jane Austen’s characters (as they have been adapted in modern film) may change the ways in which Austen is (re)produced, consumed, shared and read today, and also enable digital natives to appropriate Austen’s texts for their own cultural, social and/or political agenda. More specifically, we shall focus on how memes based on stills from Northanger Abbey’s 2007 adaptation share the novel’s self-reflexivity, seducing millennials into the literary landscape of 1790s popular culture, in which Austen’s own reading habits were formed. Thus, as we shall see, Northanger Abbey memes interact simultaneously with the popular culture of the present and the past, shedding light on themes as widespread as ‘participatory culture’, as well as on the genres of the Gothic and ‘clerihew’. We shall, furthermore, examine a series of memes based on Mr. Darcy stills from screen adaptations of Pride and Prejudice and their repercussions in regard to contemporary perceptions of masculinity and new re-imaginings of heterosexuality. Austen’s most popular hero, composed, proper and propertied Mr. Darcy, we argue, stimulated both revised versions of hegemonic masculinity and harmonious alliances between strong men and spirited women. The Darcy-inspired memes are, furthermore, not only reflective of modern-day concerns about devising viable patterns of masculinity that may educate men in a post-#MeToo era, but also inventive in broadening the current Austen fandom and suggesting alternative modes of heteronormativity. Mr. Darcy, no longer claimed exclusively by female followers, is, in other words, both idolized for achieving a balance between power/aloofness and sensibility, passion and self-discipline, kind-heartedness and sturdiness, while at the same time he is exploited for the queer potential of his partly self-contradicting qualities.

2. Muslins and Chill?

If size and wit are two elements that make Austen and memes so compatible, as mentioned above, we find it pivotal to initiate our discussion by elaborating on a particular aspect of their shared wit, namely that related with counterfeit. Dawkins’ term, as its etymology indicates, is an abbreviation of the ancient Greek word ‘mimeme’ (

μίμημα) (

Dawkins 2006, p. 249), which denotes anything imitated or fake, any copy or simulacrum (

Liddell and Scott 1996, p. 1134). It is interesting to note here that Austen’s writing career began with a sham, that is, her notorious Gothic parody,

Northanger Abbey. It is equally noteworthy that the novel is a sham of a genre that embraces sham, for the Gothic itself has been a

mimeme, after all, since its inception, obsessed as it was with presenting itself as a copy of something else and inviting for constant rewriting, transgression of boundaries and reappropriation of tropes. This fascinating

mise en abyme in

Northanger Abbey stimulates interaction between more established and less acclaimed forms of writing and points towards the capacity of Austen’s stories to generate themselves incessantly.

Northanger Abbey’s Gothic allure that hovers between authenticity and fakeness is very much alive today, (re)produced and shared in shorthand by Austen fans through contemporary digital meme culture. Indeed, the witty internet memes inspired by the novel’s Gothic strand largely share its qualities, as we shall see, attesting to Jerrold Hogle’s definition of counterfeit Gothic as a combination of ‘playful fakery’ with a ‘dim nostalgia for the earlier times’ (

Hogle 2009, p. 111).

The

Northanger Abbey memes circulating online chiefly comprise recurrent stills culled from the homonymous

Jones (

2007) ITV film adaptation by Jon Jones—starring Felicity Jones as Catherine Morland and J. J. Field as Henry Tilney—with superimposed catchphrases of different kinds, such as key snippets from the novel or satirical headlines trending online. The image macro we wish to focus on here (

https://mobile.twitter.com/HenryTilney6/status/1225498201832161282?cxt=HHwWhICwkeSH7IEiAAAA,

Twitter 2020) bears the question ‘Muslins and Chill?’

2 (which does not exist either in the novel or the film script), added to a still-image thirteen minutes into the film (0:13:40), when Catherine and Henry dance together at a ball on their first meeting and the camera zooms in on the actor’s face. Created by the popular social media community ‘Drunk Austen’ (now closed down and partly replaced by ‘bookhoarding.wordpress.com’), ‘Muslins and Chill?’ is a characteristic sample of their posts, comprising ‘funny Austen-related pictures, links, and memes’ (

Krueger 2019, p. 383). The meme in question distills the essence of the novel, serving as an entry point into its layering of joke upon joke, sharp narrative irony and participatory reading experience, qualities that in the film remain largely underdeveloped. Catherine and we are cordially invited to the ‘muslins and chill’ game, by a smirk and sardonic wink of a Gothic hero, or is he not one? The meme playfully raises generic expectations, which is exactly what happens in the novel, whereby the reader shares Catherine’s seduction by ‘muslins’ (the 1790s material culture of fashionable fabrics, laces and false manners) and ‘chill’ (the 1790s vogue of the literary Gothic). If Austen’s novel is, according to Marilyn Butler, a game ‘you must be a novel-reader to play, or you will not pick up the clues’ (

Butler 1995, p. xvi), then the participatory nature of such memes could bridge reading habits more than two centuries apart by enticing millennial fandom into the novel’s late eighteenth-century mischievous narrative.

How is the reader of

Northanger Abbey caught in the net of Austen’s playful mockery? The novel’s title,

Northanger Abbey, foregrounds the notion of the counterfeit as an inherent quality of the Gothic in an epoch hot with Gothic thrills when ‘no fewer than thirty-two novels had been published containing the word “Abbey” in their title’ (

Benedict and Le Faye 2006, p. xxx). Published posthumously in 1818, ‘North-hanger Abbey was written about the years 98 & 99’, according to a memorandum by Austen’s sister Cassandra in 1817 (

Southam 1964, p. 53), almost simultaneously, that is, with the celebration of the Gothic in 1800 by the Marquis de Sade as ‘the necessary fruit of the revolutionary tremors felt by the whole of Europe’ during the French Revolution (

de Sade 1990, p. 49). The spine of the novel is formed by seventeen-year-old Catherine Morland’s fascination with ‘horrid’ books,

3 one of the names the immensely popular genre went by at the time. Gothic novels were chiefly identified as ‘romances’ or ‘terrorist’—revealing their associations with French radical politics. No matter their name, their machinery soon evolved into a recyclable set of motifs and narrative devices, so easily recognizable that recipes for their creation regularly appeared in journals. An anonymous article on ‘Terrorist Novel Writing’ published in 1798, for example, ends as follows:

Take—An old castle, half of it ruinous.

A long gallery, with a great many doors, some secret ones.

Three murdered bodies, quite fresh. As many skeletons, in chests and presses.

An old woman hanging by the neck; with her throat cut.

Assassins and desperadoes ‘quant suff’.

Noise, whispers, and groans, threescore at least.

Mix them together, in the form of three volumes to be taken at any of the

watering places, before going to bed

PROBATUM EST.

The playful Latin postscript, originally used as a testimony that a recipe has been proved or tested, could serve as a title for Northanger Abbey’s famous scene, in which the conventions of the genre are appropriated by Henry so as to tease Catherine’s immersion in the literary Gothic on their way to visit his family home, Northanger Abbey. ‘And are you prepared to encounter all the horrors that a building such as “what one reads about” may produce?—Have you a stout heart?—Nerves fit for sliding panels and tapestry?’ (p. 161), he playfully asks her, at the outset of his three-page-long narrative filled to the brim with familiar Gothic clichés, much like the above recipe: gloomy chambers, mysterious chests, an ancient housekeeper, subterranean passages, ruinous buildings, a mysterious portrait, a haunted abbey, a violent storm, and secret doors are teamed together by Henry to raise her expectations to the highest pitch. This is the ‘chill’ part of the meme game that we, along with Catherine, are invited to play by digital Henry’s farcical archness, so appealing to the Janeite fandom. Obviously the meme winks at the novel’s counterfeit horror experience, which is filtered through ‘what one reads about’, self-reflexively exposing its fictional nature.

Let’s play, then. During Catherine’s first night at Northanger Abbey a storm that rages outside further fuels her anticipation of ‘dreadful situations and horrid scenes’ (p. 171). Her subsequent discovery of a seemingly mysterious manuscript hidden in a suspicious chest proves to be a mere ‘inventory of linen’ (p. 176), an old laundry list: ‘Shirts, stockings, cravats and waistcoats’ (ibid.) substitute imaginary skeletons, murder bodies and deadly secrets in the novel’s most renowned plot twist. Catherine’s/our deflation of expectations and keen disappointment over the found parchment has incited the creation of a number of memes. ‘When you think you have stumbled onto a mystery but you’ve literally found a laundry list’ the phrase on the next meme (

https://m.facebook.com/AustentatiousLibrary/photos/a.625212180936604/3707520892705702/?type=3&source=54,

Austentatious Library 2021) in focus reads, laid over a template created (via the meme generator ‘Mematic’) by three consecutive still-images of Catherine, one hour (1:03:05–1:03:20) into the same 2007

Northanger Abbey film adaptation, where the display of different facial expressions clearly conveys the gradation of her feelings from eagerness to disappointment to frustration. The meme’s catchphrase, which does not exist either in the film script or the novel as such, serves as a handy-to-non-Janeites summary of the episode illustrated by the template, opening up the possibility for its reappropriation to those who have never read the novel or seen the film. Thus, the meme resonates with a wider internet community and is freely used out of the novel’s or the film’s context online, in social media platforms, multiplied, shared and customized as an emotional reaction/facial response, or a humorous means to communicate any kind of disillusionment. Through the meme we become Catherine while Catherine becomes one of us, summoning new fandom around the novel.

To discuss the memes that reappropriate

Northanger Abbey’s key elements is to deal with contemporary fan-made material, but it is also to follow the author’s own first steps, as the novel self-consciously exhibits its connection to the popular fictional material of its time, being as Robert Miles has observed, ‘a novel exactly of its moment’ (

Miles 2002, p. 57). Through Henry’s employment of ‘the lexicon of the Gothic in clusters of conventional signs’ (

Byrne 2014, p. 177), for example, the novel registers the successful generic recipe at the height of its vogue. On a metatextual level the ‘laundry-list’ meme could function as a demonstration of the readers’ frustration of expectations for a fully-fledged Gothic mystery, or an educational tool (for Austen or Gothic-focused courses) alerting millennials to close reading so as to pick up the clues of how the novel taps into the 1790s Gothic ‘recipe’. To equate the genre to the sum of its early conventions created what in 1990 Eugenia C. DeLamotte denounced as the ‘shopping-list approach’ to eighteenth-century Gothic fiction (

DeLamotte 1990, p. 5), or what Diane Long Hoeveler has later rephrased as the ‘the generic laundry list’ (

Hoeveler 1998, p. 2). It is now common consent that ‘the Gothic is not merely a literary convention or a set of motifs: it is a language’, as Victor Sage and Allan Lloyd Smith succinctly put it in 1996 (

Sage and Smith 1996, p. 1). However, as the obsolete idea of ‘laundry-list’ Gothic is undeniably part of the history of its reception, the laundry-list meme could serve, we think, as a whimsical illustration of the fact that the Gothic recipe did exist and has been tested, by

Northanger Abbey’s Henry among others. PROBATUM EST.

When Catherine, an avid reader of ‘horrid’ books, asserts she could spend her whole life in reading Ann Radcliffe’s

The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), her friend Isabella, alternatively, provides a list of seven popular fictions of the kind: ‘Castle of Wolfenbach, Clermont, Mysterious Warnings, Necromancer of the Black Forest, Midnight Bell, Orphan of the Rhine, and Horrid Mysteries’ (p. 33). Known as the ‘Northanger novels’ or the ‘Northanger canon’, these ‘sidelong glances at popular fiction have the added effect of calling attention to the fictionality of

Northanger Abbey itself’ (

Neill 2004, p. 164) while designating, we think, the act of reading—and misreading—as a central theme in the novel. Long before digital Catherine’s misreading of the laundry list in our age of digital memes, the act of reading has been the theme of the novel’s arguably first fan-made material, an illustrated clerihew (

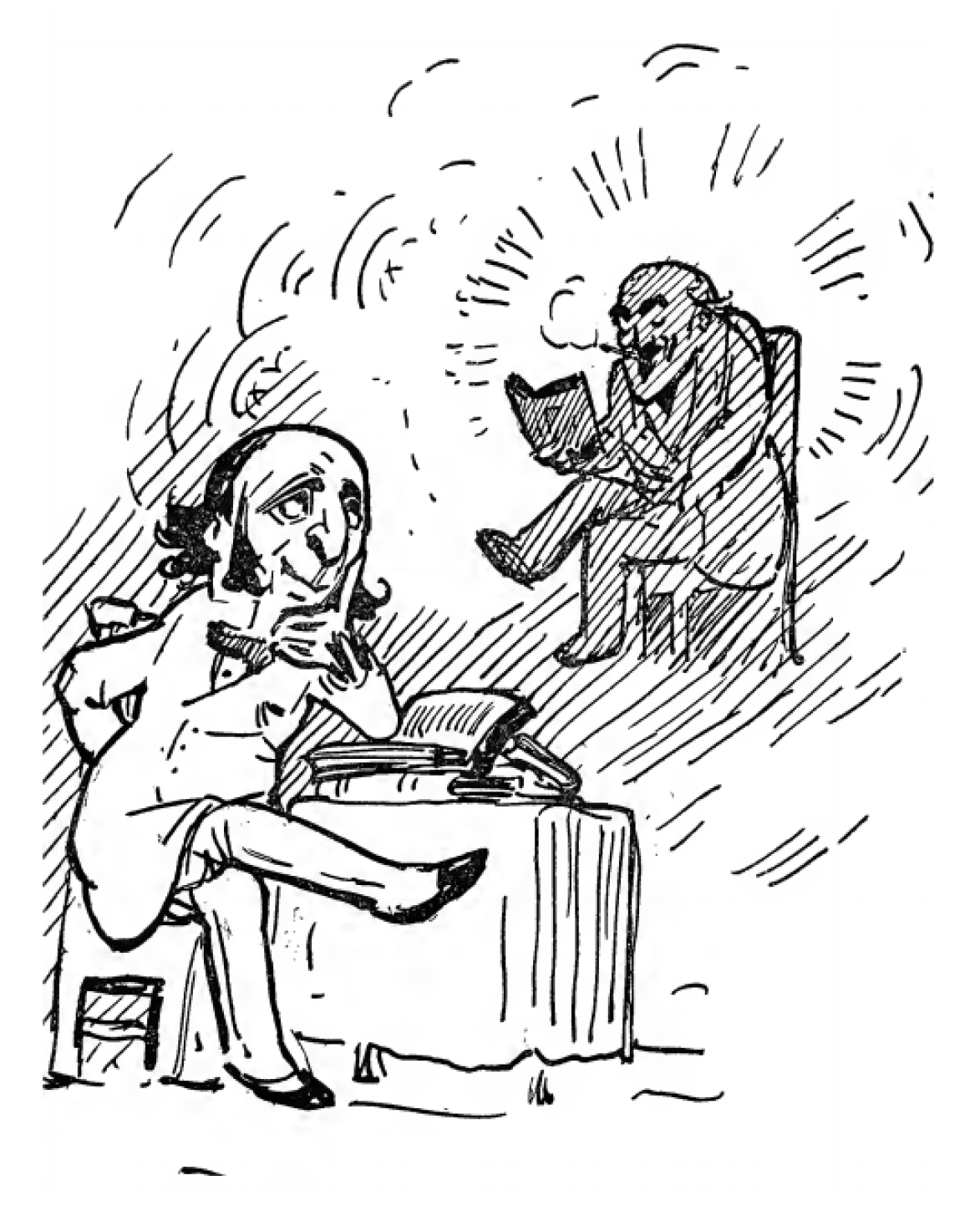

Figure 1) created by G. K. Chesterton and published in Bentley’s Biography

for Beginners in 1905:

The novels of Jane Austen

Are the ones to get lost in.

I wonder if Labby

Has read Northanger Abbey

A clerihew—a popular in the 1890s four-line humorous verse named after its creator, Edmund Clerihew Bentley—usually captured a humorous or absurd characteristic of a famous person. ‘Labby’, here, is the nickname of Henry Du Pré Labouchere (1831–1912), English journalist, theatre owner and radical politician, renowned for his attacks on Queen Victoria. The light-hearted epigrammatic rhyming text, created by an aficionado of the novel, accompanies a pen-and-ink illustration (by Chesterton too) with two cartoon figures (Chesterton and Labby?) depicted absorbed by/in the process of reading. The clerihew could have easily turned into a meme with the text (any of the two rhyming pairs) superimposed on the illustration, if Chesterton, who named

Northanger Abbey ‘a small masterpiece’ in ‘The Evolution of Emma’, was our contemporary (

Chesterton 1920, p. 87). The novels of Jane Austen are, still, the ones to get lost in, offline and online, due to their sharp wit, wry social commentary and polyphonic discourse. Memes can refresh the ways Austen is shared and read today, enabling new readings of texts: Catherine enjoys an immersive experience into the Gothic which has long fascinated fandom as it resonates with our own immersion in digital culture, hovering between authenticity and fakeness. Muslins and chill anyone?

3. I Was Darcy Firth

If the ‘chill’ part of the meme, discussed in the section above, throws light into Austen’s frisky double-voiced discourse, the ‘muslin’ part points towards Henry Tilney’s uncategorizable gender performance, as his expertise on fabrics and fashion questions the fixity of the Regency gender norms. Moving beyond the level of a surface parody, Henry’s interest in journal writing, his preoccupation with the affairs of the female characters, the Gothic fantasy he shares with Catherine (a genre that by definition embraces difference and queerness),

4 or his final defiance of patriarchal authority in marrying Catherine, are indications that he resists gender binaries and embraces what have traditionally been identified as ‘feminine’ qualities. This challenge of an established type of masculinity, as well as the need for its reform, are evident in many Austen heroes, especially Mr. Darcy, and have become trendy themes of Austen-memes. In the sections that follow, we will examine how a variety of Darcy memes contribute to the crisis in masculinity both before and after the #MeToo era, proposing Austen’s hero as an educator on benevolent masculinity, and inviting an all-sex group of Janeites to encompass diversity and more imaginative expressions of desire.

These producers of Austen’s diverse digital afterlives are predominantly women, contemporary versions of the so-called Janeites, who, according to Nicole Peters, are middle class, white, female fans.

5 Inspired mostly by the two very well-received 1995 and 2005 adaptations of

Pride and Prejudice, by Andrew Davies and Joe Wright respectively, see (

Davies 1995;

Wright 2005), Austen’s modern devotees fantasize their flight to the age of Regency, in the hope of encountering their own impeccable Mr. Darcy. Interestingly, Davies’ adaptation ventured to add focalization on Mr. Darcy, an element that does not exist in the novel, and explore his male perspective and desires more explicitly, making him thus even more appealing to modern audiences. Alongside lace, feathers, bonnets, swelling cleavages, and sisters confessing, the film is spiced with breeches, top hats, side burns, and Mr. Darcy fencing, horseriding, bathing and swimming. Facebook pages, like The Jane Austen Fan Club or The Greek Jane Austen Fan Club, resonate a strong nostalgia for both lace and top hats and are flooded with a plethora of memes, in which recurrent film stills of Colin Firth or Matthew Macfadyen, the Mr. Darcys in the 1995 and 2005 adaptations respectively, are combined with catchphrases like, ‘I blame Mr. Darcy for my high expectations of men’, ‘Jane Austen: Giving women unrealistic expectations since 1813’, ‘All women desire Mr. Darcy. Unfortunately, all men have no idea who that is’, ‘Keep calm and marry Mr. Darcy’, or ‘A truth universally acknowledged. You either love Colin Firth as Mr. Darcy or you’re wrong’.

Colin Firth ‘was Darcy firth [

sic]’ (

https://m.facebook.com/JaneAustenCentreBath/photos/a.162232580491841/1120778951303861,

The Jane Austen Centre 2016) as he declares in one of the hundreds of memes focused on him, and claims the lion’s share in women’s hearts. In his wet clothes (coming out of the Pemberley lake in the scene which Davies devised in his film), and with his penetrating gazes, and irresistible sex appeal, Firth’s Darcy elicited a whole craze, well known as Darcymania, in the 1990s and beyond. But why all the fuss about a Regency wet shirt? To answer this question, we will have to look at the 1990s through the prism of the late eighteenth century and trace the common concerns in both time periods regarding gender roles, that are, of course, reflective of larger political worries. Both American and British models of masculinity in the 1990s were evidently undergoing a new crisis, which, as the revitalized cultural immersion of the 1990s in Austen suggests, shared a lot with the masculinity crisis of the late eighteenth century. During the unstable and insecure Regency period, when the terrifying paradigm of the French Revolution was still haunting the English upper classes, the need to invent and promote a reformed model of benevolent propertied authority was more imperative than ever before. The stability of the English nation, class system, and

status quo depended on a kind of benevolent masculinity, the caring and loving patrons and estate holders who, like Mr. Darcy, would be willing to reform their haughtiness, vouchsafe agency to their female companions, and embrace the newly rising middle classes. In the first part of the novel, Mr. Darcy may have been scornful and dismissive of the Bennets and the neighboring ‘four and twenty families’ (

Austen 2004, p. 32) with whom they socialize in the country, or their Cheapside relatives engaged in trade, but he soon learns that in the aftermath of a declining aristocracy, the strength of the nation depends on a harmonious symbiosis of the propertied rulers of the country and the middle classes. The consequences of Mr. Darcy’s marriage to Elizabeth extend beyond the private sphere of the two, or their families, to the public domain and, for that matter, the future of the whole country. If Austen has undoubtedly shown us that marriage is a public matter,

Pride and Prejudice has gone as far as proposing how a marriage may prevent (or could have prevented) the French Revolution, as Isobel

Armstrong (

1998) has so intriguingly argued. It is, consequently, Mr. Darcy’s ingenious new model of masculinity that saves the Bennets from impoverishment and, more importantly, the nation from decay, or, in the worst case scenario, a violent insurrection.

What is it, though, that Mr. Darcy had to offer to the crisis in masculinity that broke out in the 1990s and what exactly has made him such a widespread cult figure ever since? A few notes on what the crisis entailed first: as a number of scholars, as a number of scholars (

Kimmel 2017;

Robinson 2000;

Hunt 2008;

Connell 2005) have argued, since the late 1960s, with the civil rights movement, second-wave feminism, as well as gay activism, the notion of the subject has been under scrutiny. In the context of postmodernism and poststructuralism, moreover, and with the publication of books like Judith Butler’s

Gender Trouble, that introduced the notions of the constructedness of gender and sexuality and even defied the sex-gender-sexuality continuum, the 1990s posed a strong challenge ‘not only [to] the power of heterosexual men but also the worth of their masculinity’ (

Hunt 2008, p. 464). At times when the dominance of white, Western, heteronormative masculinity has more than ever before been challenged, Mr. Darcy’s bragging remark in a recent meme: ‘Ah, To be young, rich, white, male, college-educated, straight, and in love’, is beyond all imagination, unless perceived as a caustic form of self-criticism. Colin Firth’s relaxed and confident smirk in the picture, however—a still from an early part of the series most probably, when he is still too self-assured of his own importance—suggests nothing of the kind. In the eyes of the millions of his female fans, Mr. Darcy is the personification of perfection, exactly because he is ‘young, rich, white, male, college-educated, straight, and in love’.

This would have been effortlessly interpreted as a backlash to traditionalist gender roles, if not considered within the context of the character’s eagerness to mitigate his self-esteem. For, the key to Mr. Darcy’s triumph lies in his mastering contradictions. Indeed, while Mr. Darcy never abandons the domain of hegemonic masculinity, he complicates it, torn as he is between antithetical forces: his ancestral past and the new middle classes, his attraction to Elizabeth and his reasoning against it, his duty towards authority and the desire to defy it in the pursuit of personal needs. Another Colin Firth template meme summarizes Mr. Darcy’s inner strife most tellingly: ‘I HAD A WILL OF IRON TILL YOU BENNET’ (

https://me.me/i/i-had-a-will-of-iron-till-you-bennett-jane-51ef83b266274c639b5675c09bd694ad,

MEME 2019a). At the risk of being called effeminate, Mr. Darcy gives in to sensibility, and eventually finds the right balance between reason and sentiment, vigour and tenderness, force and compliance. As

Kramp (

2007,

2018) has convincingly argued, this was exactly the right antidote to the two dominant trends that dealt with the masculinity crisis in the 1990s; on the one hand, the aggressive and competitive model of man as a wild man, advocated by the American poet Robert Bly in his Iron John initiation rites, and, on the other hand, the chaste and godly model of man as a fatherly figure, which the Promise Keepers promoted in their Evangelical meetings. Compared to Mr. Darcy’s sophisticated vigour and self-control these are nothing but crude attempts to reestablish strong hegemonic structures. Austen’s Darcy knows how to be proud of his social position and economic supremacy and learns how to make best use of it for the benefit of everyone around him, not just himself; he acknowledges his (hetero)sexual virility, but is perfectly capable of suppressing it, if necessary; and, most strikingly, he embraces his feelings, is courageous enough to join Elizabeth’s blush (‘Their eyes instantly met, and the cheeks of both were overspread with the deepest blush’, p. 190) and even willing to be laughed at (pp. 291–92).

It is exactly Mr. Darcy’s willingness not only to be educated, but also to educate his male peers, or reform those gone down the wrong path, that has elevated him to a universal mentor figure on benign masculinity in times of hashtag activism. The upsurge of the #MeToo movement, especially, a campaign firstly launched by Tarana Burke in 2007, which acquired new and powerful momentum after the public exposure of Harvey Weinstein’s incidents of sexual misconduct in 2017, ushered a new era in our attitudes about sexual misconduct, rape culture and appropriate masculine behaviour. What the movement has been targeting at mostly is the dismantling of a specific form of masculinity that could encourage such behaviour in men, that is, toxic masculinity.

6 The term refers to a series of traits and behavioural patterns that are considered as traditionally masculine in certain societies, such as aggression, ‘predatory heterosexual behaviour resulting in sexual and domestic violence’, but is also related with ‘the suppression of men’s emotions leading to emotional and mental health issues’ (

Waling 2019), or in general the detrimental effects of conformity to gender stereotypes.

Among the surge of oppositional responses #MeToo has instigated was a new hashtag, #HowIWillChange, conceived also in 2017 by the Australian journalist Benjamin Law, urging men on Twitter to consider ways in which they may have been adopting the pattern of toxic masculinity and prompting them to change. Although many response tweets expressed a reluctance to change or even outright enmity, a significant number of users were eager to accept responsibility, work towards egalitarianism, and even provide a lesson for younger generations on the subject (

PettyJohn et al. 2019). In this crucial historical moment of a social and sexual crisis, Mr. Darcy emerges as a meme idol and precursor to #HowIWillChange, disposed as he is to denounce an improper patriarchal education that has implanted hegemonic tendencies in him and substitute it with an education coming from an equal partner in marriage. As he gratefully admits at the end of the novel, Elizabeth taught him ‘a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous’ (p.328); a point encapsulated succinctly in the pun of Darcy’s pronouncement in a meme already referred to above: ‘I HAD A WILL OF IRON TILL YOU BENNET’, and sharply contrasted with Henry Tilney’s dismissive: ‘HEY GIRL, NATURE HAS GIVEN YOU SO MANY TALENTS, IT’S NEVER NECESSARY TO USE MORE THAN HALF’ (

https://heygirlliterarymen.tumblr.com/post/105331405769,

Hey Girl, Literary Men of Tumblr 2014), in another meme caption. Having accepted schooling by Elizabeth, Darcy can now function as a proper tutor to his peer Bingley, and also guide unrighteous Mr. Wickham away from his toxicity. The ‘Bennet/bend it’ double entendre, summarizes Darcy’s flexibility as a key character trait, an edification pattern that should be lauded and emulated.

4. Therapy Is Nice, but a [Hand Flex] Is a Lot Faster and Cheaper

‘It is a truth universally acknowledged. You either love Colin Firth as Mr. Darcy or you’re wrong’. The meme caption above is one in a series of similar memes that rightfully claim for Firth, as we have seen, the title of the ‘first and true Mr. Darcy’, world-widely adored as he is in his six-hour-long—and admittedly very close to the fictional image—impersonation of a seductively stubborn romantic hero. If you are beginning to wonder what chances Macfadyen’s version of the part stands when competing with such a giant idol, the answer is: a lot, as a 2019 Twitter poll, has proven. When asked to compare Firth’s and Macfadyen’s performances of Mr. Darcy and express their preference, millennial Janeites certainly preferred Macfadyen’s unkempt, awkward, and brooding Mr. Darcy over Firth’s more standoffish one, who was favoured mostly among boomers and Generation Xers.

7 Macfadyen, it seems, has added a special appeal to the character that even Firth devotees cannot resist. He is undoubtedly more realistic than Firth as a Regency man in his not-immaculate-at-all clothes and disheveled hair; more wet in his rain-soaked proposal; more deeply pining, as his large blue eyes reveal; more sensitive and passionate and, consequently, more susceptible to self-torment and destruction. Furthermore, it will be argued, Macfadyan’s Darcy has not only exploited the character’s sexual tension to the fullest, but also spiced it with introversion and sensitivity (a form of emotional masturbation) in ways that undermine the model of dominant heterosexual masculinity he is associated with in more subtle manners than Firth.

Among Macfadyen’s renowned additions to the part is his iconic hand flex about half an hour into the film (0:25:23–26), when the camera zooms in on the actor’s hand a few seconds after he has helped Elizabeth (Keira Knightly in the film) into a carriage, as she and her mother and sisters are departing from Netherfield. Their hands touch for the first time (Elizabeth’s hand is notably ungloved), and, as he is walking away, his muscles flex, causing his hand to stretch for a couple of seconds, as if electrified, and contract again. Although not originally scripted, but improvised by Macfadyen in one of the rehearsals, as the actor explained in an interview, the hand flex became a distinguishing gesture of millennial Mr. Darcy and has captivated the crowds ever since. A whole blog is dedicated on #thE DARCY HAND FLEX on the social networking site Tumblr where fans proclaim Mr. Darcy’s hand flex ‘the sexiest scene in cinematic history’, and one of the three ‘horniest moments in film history’.

8 ‘Fuck porn’, an ardent blog follower exclaims, ‘have you seen Mr. Darcy flex his hand away from Elizabeth as if they got burnt by the onset of feelings in Pride and Prejudice? Yes, that’s the kind of romance I want with you’. What is it though that has made this cameo gesture the quintessence of Darcy’s masculinity? Wrights’ lens, it seems, has been synchronized here with Austen’s microscopic gaze, alerting modern viewers to detail and training them to close reading. Breaking the emotional distance between audience and subject, this close up frame allows a deeper intimate look into the character’s personality, despite his alleged detachment. Following the two-second shot of Darcy’s hand supporting Elizabeth’s as she mounts the carriage, the three-second shot of the hand flex, sums up the inner strife of the character in the first part of the book: it is an automatic bodily reaction loaded with feeling that cannot be expressed otherwise, a genuine self-confession of Mr. Darcy’s passion for Elizabeth, a hopeless attempt to both cling on to her and shake her (and her inferior connections) off his skin (‘It is a truth universally acknowledged. Click it or ticket. Pride [or bride]‘, one hand-flex meme suggests) (

https://me.me/i/it-is-a-truth-universally-acknowledged-clickitor-ticket-memegenerator-net-it-7cb24614ca4d44bebe88a8ce48f0eac5,

MEME 2019b). Even, perhaps, a private acknowledging of his hand power.

While the hand flex is celebrated by some blog followers as the apex of heteronormative masculinity, an inspiration even for gay men to go straight (‘just watched pride and prejudice [2005] and i am now renouncing my homosexuality. Im Straight I simp for Straight ships. Hets get all the rights’), others take the opportunity to build on its queer potential; the hand flex becomes a case of autoeroticism/onanism (‘its possible that i have, how u say, fúckédúp my hand’), or homoeroticism (‘The Destiel eye fucks are equivalent to Darcy’s hand flex’). This final mention of two characters from the American TV fantasy series

Supernatural, demon-hunter Dean Winchester and angel Castiel (referred to as the ‘Destiel’ couple), alludes to their homosocial closeted romance, and takes the hand flex to a different level. Austen’s bawdy humour and latent queerness has been explored since the 1990s by a number of critics, such as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Terry Castle, Claudia Johnson, Clara Tuite, Jill Heydt-Stevenson, or William H. Galperin (

Sedgwick 1993;

Tuite 2002;

Galperin 2003;

Castle 1995), who have written extensively on same-sex desire in her novels, as her means of covertly questioning patriarchal authority and fixed gender roles. The word ‘queer’, after all, E. J. Clery explains ‘[i]n the early nineteenth-century lexicon carried the sense of an impropriety verging on the antisocial including, explicitly, a resistance to heterosexual norms’ (

Clery 2001, p. 160).

Pride and Prejudice, of course, makes its own lewd suggestions both to phallic power and autoeroticism, as Heydt-Stevenson has already discussed (

Heydt-Stevenson 2000). In the scene in which Miss Bingley comments on Mr. Darcy’s pen (‘I am afraid you do not like your pen. Let me mend it for you. I mend pens remarkably well’), for example, his dismissive reply is a hint to self-reliance and satisfaction: ‘Thank you—but I always mend my own’ (

Austen 2004, p. 35).

We would now like to focus on a hand-flex meme (

https://www.tumblr.com/blog/view/obscurelittlebird/184629962711?source=share,

Obscurelittlebird 2019) that appropriates exactly this Mr. Darcy-giving-in-to-solitary-vice idea. It borrows from a popular meme template consisting of two parts: on the upper (standard) side of the template, the superhero Wolverine lies in bed and gazes into a photo frame he holds in his hands; on the lower (customized) side, we see a close up of the frame, which in our case is a photo of Macfadyen’s hand flex caressed by Wolverine’s fingers. Besides it being surprisingly refreshing to see Austen in a super-hero context that bears little resemblance to the ‘girly’ fandom that usually claims her on social media, it is also intriguing to explore the signification of Wolverine’s soft touch of Mr. Darcy’s hand. Or, would that defeat the purpose of a meme? The Wolverine meme is a widely circulated meme template, meme makers or users or digital natives will warn us, not generated for Jane Austen specifically. There is, consequently, no point, they may argue, for a detailed semiotic analysis; the template was simply there and, one day, an Austen fan decided to use it in order to make a joke about Mr. Darcy’s hand flex. This is unarguably the case. Still, author’s intention aside, the meme is provokingly recontextualizing an Austen hero in ways that propose stimulating interplays and call for further investigation. Siding with Limor Shiffman’s definition of internet memes as ‘multiparticipant creative expressions through which cultural and political identities are communicated and negotiated’ (

Shiffman 2014, p. 177), we shall venture an exploration of how Wolverine’s caress may enable revisionist readings of Mr. Darcy’s identity. Is it a sign of admiration and endorsement of his masculinity, or his pining away over him? Is the meme queering Mr. Darcy in implying that his irresistible charm can infect a more universal audience than female Janeites? And is it also rewriting Wolverine’s/superhero masculinity as more flexible and experimental? Let us begin by introducing Wolverine’s character and then tracing the points at which Darcy and this superhero converge.

Born in the post-Vietnam war America, like most forceful super- or antiheroes, Wolverine (also known as James Howlett by birth-name, or Logan) is a Canadian Marvel Comics character, who appears mainly in the

X-Men series, with a long and complex history. To briefly summarize Wolverine’s most principal physical characteristics: he is a mutant who has developed sharp animal senses and possesses increased bodily power largely due to three retractable claws in each hand. His bone claws, which cut through his flesh every time he unsheathes them, causing him slight pain, are extra resilient, as, like his whole skeleton, they have been coated with adamantium and can cut through metal and stone even. What adds to Wolverine’s invincibility is his exceptional so-called healing factor, which allows him to restore damaged tissues of his body, making him thus impervious to maladies and poisons. As far as his personality traits are concerned, he is a proficient leader and trustworthy ally, dedicated to duty, but also resisting hostile authority (

Flores 2018, p. 9), if needed, and a cynical recluse best described in his catch phrase: ‘I’m the best there is at what I do, but what I do best isn’t very nice’ (

Flores 2018, p. 14). No doubt Wolverine is a fascinating and multi-layered antihero, as Suzana E. Flores has shown in her in-depth analysis of him, but for the purpose of this essay, we will limit ourselves to his dualistic nature of ‘tough exterior combined with a soft heart’, which is perhaps Darcy and Wolverine’s most striking common reference (

Flores 2018, p. 17). They are both antisocial, cynical, and emotionally distant, while being caring and protective at the same time, although, of course, to a different degree and in different ways. Yet, while Wolverine’s claws have a destructive power (even if unsheathed in defense only), Darcy’s extending fingers can harm no one. On the contrary, they seem to have healing effects. ‘Therapy is nice, but a [hand flex] is a lot faster and cheaper’, one hand-flex meme caption reads, suggesting that this basic hand gymnastics can provide a speedier solution to dealing with unexpected change or moods, regaining control, developing strategies to manage stress, or preventing self-destructive behavior.

Macfadyen’s Darcy’s hand flex is unquestionably proposing an enticing masculinity model, in which he both retains a hegemonic status and suppresses ferocity. This is the exact same pattern we have seen in Collin’s Darcy, only Macfadyen’s version inspires a homosocial bonding between a super/antihero and a Regency character via the 2005 lead actor. Wolverine’s caress may be interpreted as a worshipping gesture towards an older mentor, or an acknowledging of his gift for uniting opposing forces. This nostalgic desire to return to the 1800s or the 2000s, could be his only hope of escaping self-destruction, as his own romantic relationships with a number of women have been disastrous and his death by suffocation from the hardening adamantium is caused by the same weapon that makes him invulnerable. (How much hardening can a body endure after all?) His relaxed reclining posture and revealing tight-fitting underpants, moreover, introduce a sexual undertone to Wolverine’s absorption into Macfadyen’s hand, or, should we say, into the power of his own hand and the pleasures it may bestow? Besides sanctioning Darcy’s masculinity, Wolverine is also magnetized by it and either yearns for their union as their merging fingers suggest on the lower side of the meme, or can’t wait to experience the thrills that his own will lead him to. In this postmillennial rewriting of Darcy, his sex appeal is definitely more complicated than that of its predecessors’, reflecting both the elasticity of postmodern gender and sexual identities and the imperative demand for revisionist readings of Austen in the post #MeToo era.

5. Stone Cold Jane Austen

Misty Krueger’s 2019 article entitled ‘Handles, Hashtags, and Austen Social Media’ offers an extensive chart of Austen’s appropriation in the social media, referring to the whole gamut of contemporary re-imaginings of Austen from modest lady to courageous feminist to subversive wino even (

Krueger 2019). Likewise, in the meme sphere, Austen has definitely ventured outside the walls of a Regency ball room in search for new hybrid geographies and gender identities. ‘Jane Austen Is My Spirit Animal’ reads the caption of a meme in which she is posing as ‘Jane Austin’ in a background of skyscrapers, with a Texas hat, holding a book that bears the symbols of Texas on its cover. Even more telling is an androgynous image of Austen (

https://www.reddit.com/r/Punny/comments/g5ag11/stone_cold_jane_austen/,

Classical Art Memes 2020), in which her head (as depicted in the ‘wedding ring’ engraving) is attached to a muscular male body that resonates with hegemonic strength ideals in men. The caption here: ‘STONE COLD JANE AUSTEN’ is an allusion to the famous professional wrestler Stone Cold Steve Austin, and the repercussions of this transmutation of Austen into wrestler in an arena are multifaceted. One may read here Austen as a fighter (for gender equality most obviously); or claim that her androgynous body, and by semiotic extension her body of works, is directed to both women and men. The fact that Austen’s corpus should be devoured and cherished by men is even more pronounced in the meme in which Spiderman presses a copy of

Pride and Prejudice on his chest with an expression of adoration verging on ecstasy on his mask-face, exclaiming ‘OMG JANE AUSTEN’ (

https://www.pinterest.dk/pin/11822017744009787,

Pinterest n.d.). The message is quite clear: if Spiderman, a traditional popular icon for boys and men, loves Austen, all boys and who want to be a modern-day superhero in the post-MeToo world, should love Austen, too.

Another way to interpret the funny fusion in ‘STONE COLD JANE AUSTEN’ would be to see it as an echo of the writer’s most characteristic feature of blending opposites and mixing up voices, a deviation from the prescriptive code of masculinity that some of the memes we have discussed promote. Setting a preferred masculinity compared to the spectrum of already existing masculinities could be perceived as a regressive tendency in the third decade of the twenty-first century, when gender boundaries and dichotomies blur and in some cases even evaporate. Portraying Mr. Darcy as the ideal saviour-male may seem like a step backward for the feminist movement—are we truly, after all, in an age that we rest all our hopes in marrying ‘a single man in possession of a good fortune’? Relying on Austen-like irony and almost self-sarcastically, however, there are memes that capture the author’s line of thinking and the complexity of her characters’ revival in Web 2.0. At their strongest, memes respond to a social world in transformation, just as Austen’s novels do, and expose a series of mirrored actions; in the

Northanger Abbey memes we have discussed, for instance, Catherine Morland’s addiction to reading Gothic tales reflects Austen’s own immersion into the popular culture of her time as well as our own immersion into contemporary digital culture, where the addiction to Austen is ubiquitous. The dilemma of the sweating superhero in a meme borrowing from Jake Clark’s Tumblr comic (

https://www.facebook.com/JaneAustenDailyDose/posts/509872237469071,

Jane Austen Daily Dose 2022) involves choosing between ‘living in a Jane Austen novel’ and ‘having equal rights’. Are idolizing Mr. Darcy and fighting for equal rights mutually exclusive? Or is it possible to marry the positive traits from his masculinity paradigm and today’s demands for real gender equality and diversity, similarly to how

Pride and Prejudice marries two antithetical characters for a greater union? As meme creators, today’s prolific and successful matchmakers, would say: ‘Click it or ticket. Pride or Bride’.