Abstract

This article discusses a picture book, The Beautifull [sic] Cassandra, that was published by Juvenilia Press in 2021. The text was written by Jane Austen, most probably in 1788, and was edited and illustrated by Juliet McMaster some 200 years later. My key questions are: What are the characteristics of Austen’s text? What are the strategies that McMaster uses to illustrate the text? How do we evaluate the picture book as a whole?

Some of the material in this article appeared in my paper ‘Listening to what “the word evokes”: Juliet McMaster’s Illustration of Jane Austen’s “The beautifull Cassandra’’’ read at the international conference of the British Association for Romantic Studies, 2017, and in my articles in Japanese, ‘The Beautifull Cassandra Kou: Juliet McMaster no Sashi-e wa Jane Austen no Shouhin wo dou Tora-eruka’ (1) (Hisamori 2017) and (2) (Hisamori 2021)

1. Introduction

This essay discusses a picture book, The Beautifull [sic] Cassandra, that was published by Juvenilia Press in 2021.1 The text was written by Jane Austen, most probably in 1788 (Sabor 2006, p. xxviii) and was edited and illustrated by Juliet McMaster some 200 years later. In this article, I will examine how McMaster’s illustrations heighten elements of Austen’s text and explore how the pictures are particularly suited to Austen’s juvenilia style. I also address whether such illustrations make Austen more accessible to modern readers.

Austen’s early works were rediscovered in the 1920s. A turning point in their reception came in the late 1970s, when feminist critics started to examine them. Peter Sabor considers Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s Madwoman in the Attic, published in 1979, particularly significant: ‘Here, almost for the first time since Chesterfield’s seminal essay, the unrestrained energy of the juvenilia was made a cause for celebration, not regret’. (Sabor 2006, p. liv)

McMaster is the first to illustrate Austen’s juvenilia ‘The beautifull Cassandra’,2 but not the first to provide pictures for Austen’s work. Since the mid-nineteenth century, illustrators have attempted to capture Austen’s text in image. The best known are Hugh Thomson (1860–1920) and Joan Hassall (1906–1988); the former worked in pen and ink and the latter in wood engraving. In the course of my discussion, I will analyse one of Thomson’s illustrations from the first chapter of Pride and Prejudice (1813) and an illustration by Hassall for ‘Love and Freindship’ [sic] (1790). I argue that while Thomson’s illustration captures what is comic in Austen’s most popular novel and Hassall’s what is satirically dramatic in Austen’s highly critiqued juvenilia,3 McMaster’s colourful and ingenious illustrations breathe life into ‘The beautifull Cassandra’ and thus revitalise one of the least known of Austen’s juvenilia for readers, children and adults alike, of the present age.

Let us first examine the text, ‘The beautifull Cassandra. a novel in twelve Chapters’.4 Twelve-year-old Austen wrote this story for her sister Cassandra, her closest friend, who was then fifteen. Imitating the style of the period, Austen’s dedication exaggerates her sister’s beautiful looks and innumerable virtues. Austen then tells a mischievous story about a ‘beautifull Cassandra’ who is spoilt and goes on a reckless spree. The tale begins: ‘Cassandra was the Daughter and the only Daughter of a celebrated Millener [sic] in Bond Street’. (Austen 2006, p. 54) Deirdre Le Faye in Jane Austen: A Family Record writes: ‘the family trip to Kent in July and August 1788, with its return via London, probably inspired the London setting of “The Beautifull Cassandra” as well as teasing Cassandra with a description of how she had not behaved whilst there’. (Le Faye 1989, p. 63)

While narrating the story, Austen mocks and satirises the literary style of the period. In the second chapter, Cassandra, having stolen a bonnet that her mother has just completed for a countess, boldly sets out to ‘make her Fortune’. (Austen 2006, p. 54) A grand adventure in the style of Robinson Crusoe or Tom Jones does not follow, however, for Cassandra roams around London for seven hours and then returns home. Austen’s ‘a novel, in twelve Chapters’ consists of only 19 sentences and mocks first and foremost the long-winded narratives found in adventure/picaresque novels, whose central characters are usually male.

In the middle of the story, Cassandra takes a hackney coach to Hampstead, a village famed for its fine views. Yet, as soon as she reaches Hampstead, she orders the coachman to turn round and go back. She pays no attention whatsoever to the view. This nonsensical episode thus satirises a fashionable journey in search of the picturesque.

Austen also pokes fun at sentimental novel. Cassandra, who ‘fall[s] in love’ and elopes with the bonnet her mother has made for a countess, pays hardly any attention to a young viscount she meets, ‘celebrated’ for his ‘Accomplishments’ and ‘Beauty’ as he is. (Austen 2006, p. 54) Defying conduct books, Cassandra ‘devour[s]’ six ices in a pastry shop and, refusing to pay the pastry cook, knocks him down and walks away. (Austen 2006, p. 54)

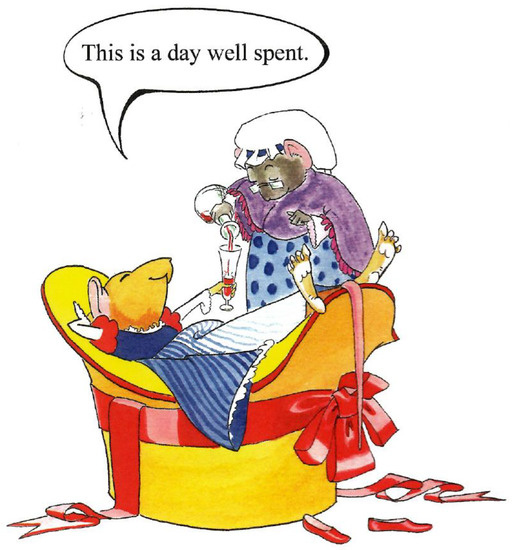

By the end of the tale, Cassandra has stolen a bonnet, knocked down a man, and paid neither the cook nor the coachman whom she hires to take her to Hampstead. Far from being reprimanded for these crimes, however, she is welcomed home by her mother at the end of the story and the heroine ‘smile[s]’ and ‘whisper[s]’ to herself, ‘This is a day well spent’. (Austen 2006, p. 56)

How should one illustrate this story of the wild Cassandra, a tale full of humour, hilarity, and wickedness? One of the difficulties of illustrating ‘The beautifull Cassandra’ lies, we assume, in the fact that this story of just 19 sentences contains hardly any physical descriptions. How does one illustrate such a story? One of Hugh Thomson’s illustrations from the first chapter of Pride and Prejudice provides a possible solution.

2. Capturing the Comic in Jane Austen

Consisting of 55 sentences, the first chapter of Pride and Prejudice tells readers a great deal. Mr and Mrs Bennet’s conversation meanders so much that we learn not only of a Mr Bingley, who is to be their neighbour, but also about Mr and Mrs Bennet: how eager Mrs Bennet is in hunting rich husbands for her daughters, how cynical Mr Bennet is with regard to his wife, about their personal habits, idiosyncrasies, and so on. We even discover which of their five daughters Mrs Bennet favours most and which Mr Bennet prefers.

Yet, there are hardly any physical descriptions. We do not even know where this conversation takes place. Could it be that Mr Bennet is sitting in room at home when Mrs Bennet comes in to talk to him? Or have they been in the same room sitting side by side or facing each other across the table? How are they dressed? What do they look like? We are given none of these details.

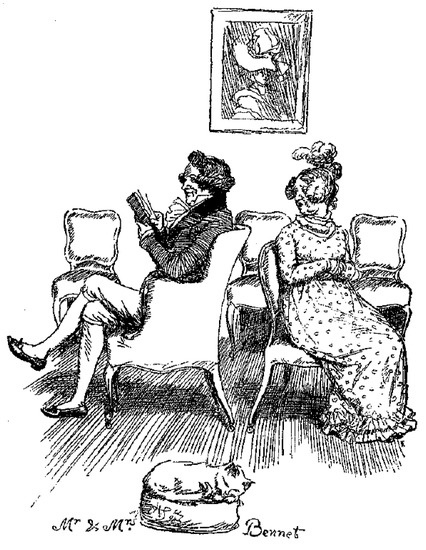

Let us see how Thomson approaches this scene. Surprisingly, in his illustration entitled ‘Mr and Mrs Bennet’, Thomson depicts the couple sitting back-to-back (Figure 1). A couple sitting back-to-back while conducting a conversation looks comic. Moreover, Mr Bennet sits in his armchair, nonchalantly reading a book as if he is no longer interested in keeping up the conversation, while Mrs Bennet turns around in her chair, scolding him. Her dissatisfied look reveals that she has failed to persuade her husband to visit the newly arrived, wealthy bachelor Mr Bingley for their daughters’ sake.

Figure 1.

Hugh Thomson’s illustration for Pride and Prejudice (Austen [1894] 2005), p. 5.

As Mrs Bennet’s body is turned two-thirds toward us viewers, her figure dominates the scene. The white colour of her dress further emphasises her figure. Despite his haughty attitude towards his wife, Mr Bennet in a dark jacket and half-buried in his armchair remains a secondary figure in the scene.

Thomson adds some props that are not mentioned in the text. In the foreground, we see a cat sound asleep on a round footrest. Behind Mr and Mrs Bennet, there are several chairs, and a portrait of a fashionable young lady decorates the wall. Could it be a portrait of Mrs Bennet painted before she was married?

All the props and figures are placed in a structurally calculated manner. If we start from the midpoint of the top portrait frame and draw a line directly downward, we will reach the edge of the left ear of the cat. The line vertically divides the scene into two. If we start from the same midpoint of the top portrait frame and draw two lines, one to reach the tip of Mr Bennet’s left shoe and the other to reach the left knee of Mrs Bennet, we will create a triangle, the left half of which encloses the best part of Mr Bennet and the right half most of Mrs Bennet. Mr and Mrs Bennet, sitting back-to-back, together form a triangle which gives the scene structural stability and suggests that their relationship is stable in its own way.

The sleeping cat on the footrest and the portrait of the young lady on the wall together create a homely atmosphere. Mrs Bennet may be discontented with her husband, who refuses to comply with her wishes, but this is evidently one of their ordinary domestic scenes, and by portraying Mr Bennet and Mrs Bennet sitting back-to-back, Thomson presents this as a humorous conversation.

Judging from this illustration, we may conclude that an illustrator selects attributes that are necessary to visualize what is at the core of the text. If the text lacks physical details, the illustrator simply invents them.

3. ‘The Beautifull Cassandra’ as Comic Animal Tale

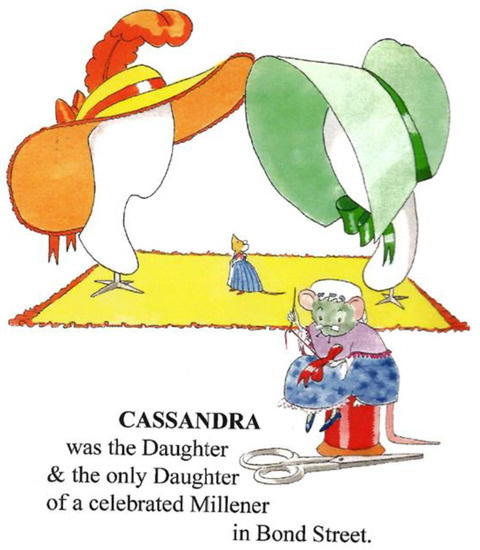

Figure 2 shows the first page of the picture book The Beautifull Cassandra.5 The picture may at first surprise us, for instead of portraying human figures, McMaster presents the characters as animals in the style of Beatrix Potter’s tales and depicts Cassandra and her mother as mice. In her ‘Afterword’, McMaster explains:

[When] I read ‘The Beautifull Cassandra’ it seemed to me like a story of Beatrix Potter’s, and I suddenly began to imagine it as peopled by animal characters. That way, it makes a splendid story for children, and as Jane Austen was pretty young when she wrote it, I thought children would like it’.(McMaster’s ‘Afterword’ in Austen 2021, p. 29)

Figure 2.

Juliet McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 1. Reproduced with permission by Juvenilia Press.

It is not surprising that ‘The beautifull Cassandra’ reminded McMaster of Beatrix Potter’s tales, for the story structure of ‘The beautifull Cassandra’ is similar to that of Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit: a mischievous child goes on an adventure and having lost a part of her/his outfit, returns home and is nursed by their mother. (Cassandra does lose her bonnet and comes home bareheaded, but receives a hearty welcome from her mother.) I will refer to this juvenile literature aspect of ‘The beautifull Cassandra’ again later in this article.

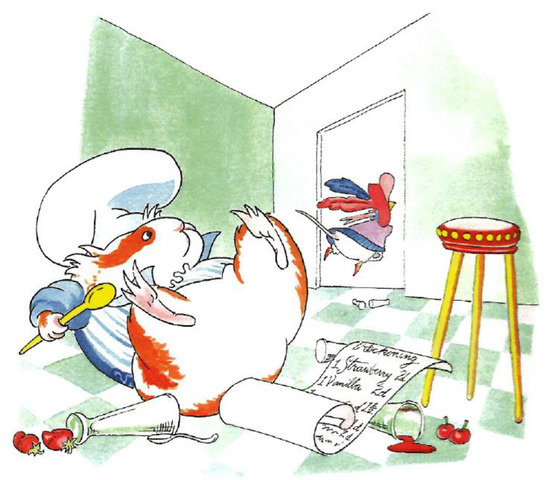

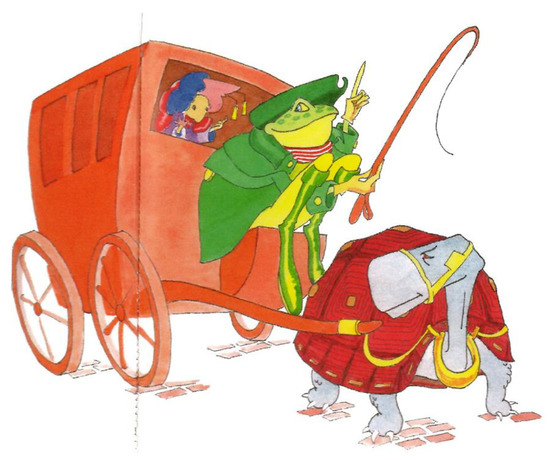

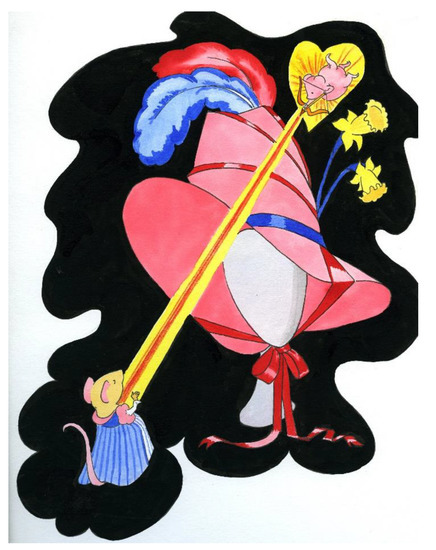

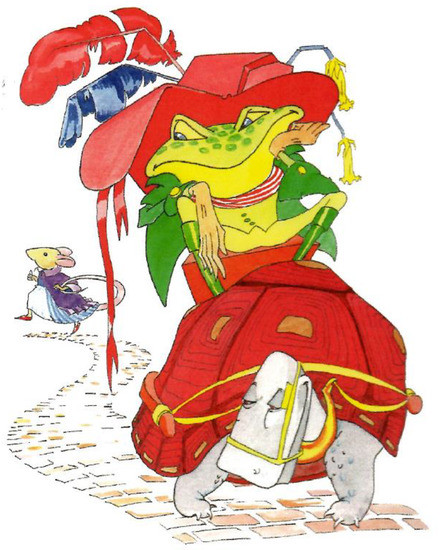

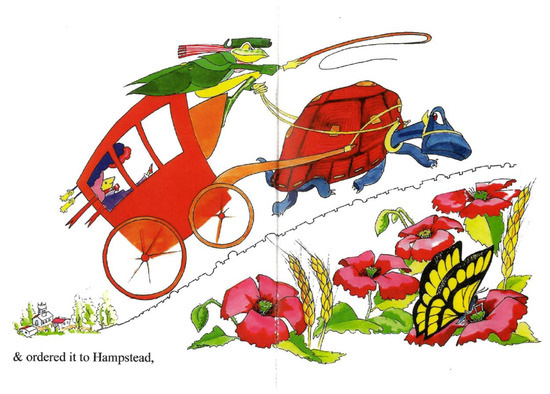

McMaster minimises young Austen’s satirical tone mimicking the literary style of her period and focuses instead on the comic ruthlessness and hedonism of the Cassandra character. In this respect, the artistic choice of using animal characters has its merits. A dominance hierarchy exists among animal characters: if one depicts the central character as a tiny mouse, as McMaster does, one implies that it is at the bottom of the ladder and, thus, one of the weakest. But look at page 11 of The Beautifull Cassandra. We see Mouse Cassandra running away from the pastry shop, having knocked down the Guinea Pig Pastry Cook (Figure 3). The power balance between the two animals, a guinea pig and a mouse, has been turned upside down. The nonsensicality, as well as the violence of the act, are thus emphasised. We may cite another example: on page 13, McMaster has chosen a tortoise, known for its slow pace, to pull the huge hackney coach that takes Cassandra from the central part of London to Hampstead (Figure 4). While the comicality of this mismatch is obvious, McMaster’s artistic decision to depict the characters as animals stresses Cassandra’s love of disrupting social and gender norms as she orders about an animal larger in size than she.

Figure 3.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 11.

Figure 4.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 13.

‘The beautifull Cassandra’, as we have already noted, is a story full of humour and slapstick. But the story’s events are only loosely connected. To bring variety and unity to the work, McMaster uses not only animal characters but also contrast and unifying motifs.

Let us examine in detail the first page of The Beautifull Cassandra. Printed at the bottom of the page is the opening sentence of the story. Tiny as she is, Mouse Cassandra attracts our attention as she stands in the middle of the picture (Figure 2). The colour of her skirt is blue, a cold colour. This is eye-catching as she is surrounded by warm colours, such as orange and green. These are the colours of the hat and the bonnet on display, while the colour of the cloth spread on the floor is yellow. This is an effective use of colour contrast.

To emphasise her close relationship with Cassandra, McMaster gives the Mother Mouse a blue skirt. Here, the colour blue works as a unifying motif. The Mother sits on a spool of thread, sewing a ribbon, but her needle seems too long and her scissors too large. Could it be that, as in Mary Norton’s The Borrowers, she has ‘borrowed’ the sewing kit from ‘big people’? Note that the Mother Mouse, finding her legs too short, uses her tail for balance. By introducing such tiny animals as mice engage in ‘human’ activities and making a colourful scene out of a mouse-run London millinery, McMaster succeeds in creating a humorous fantasy world that is a familiar feature of juvenile literature.

Pages 4 and 5 form the first double-page spread. On page 4, the text reads: ‘When Cassandra had attained her 16th year, she was lovely & amiable & chancing to fall in love with an elegant Bonnet, her Mother had just compleated [sic] bespoke by the Countess of Dash’. Here, the sentence is abruptly cut off and on page 5, McMaster presents a full-page illustration (Figure 5), as if to say that this point in the story is too crucial not to illustrate right there and then.

Figure 5.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 5.

Note the irregular outline of the illustration. Stage-lit against the pitch-black background, a pink bonnet stands tall, elegant, and alluring. It is splendidly decorated with red and blue feathers while two yellow daffodils graciously adorn the side; a bright red ribbon winds around the bonnet and a pretty bow is tied beneath the chin of the mannequin.

On the left, little Cassandra stands looking up at the bonnet as if stunned. In the upper right-hand corner, a pink Mouse Cupid who seems to have just arrived shoots his golden arrow. It swiftly travels from one side of the bonnet to the other and pierces Cassandra’s heart. The moment when Cassandra falls in love with the bonnet is thus dramatized.

If we place this illustration next to the first page (Figure 5 vs. Figure 2), we will clearly see the contrast. Page 1 creates a sense of open space, while page 5 presents a dark enclosed space. Page 1 is a day-time scene that takes place during working hours; page 5 occurs at night. In one, Cassandra is ‘guarded’ by her mother; in the other, she is ‘unguarded’. In contrast to the plain hat and bonnet on display in the illustration on page 1, the countess’ bonnet is indeed bewitchingly beautiful.

The countess’ bonnet is a unifying motif in subsequent illustrations. It becomes, in effect, one of the major characters of the story. It assumes a life of its own. The last of these is on page 19 (Figure 6). (By page 19, Cassandra has already returned from her trip to Hampstead. The Frog in the illustration is the Hackney Coachman and the Tortoise, as already mentioned, is harnessed to the coach.) Observe how shabby the bonnet now looks! The feathers are battered, the daffodils drooping and wilted, while the two ends of the ribbon dangle in a most indecorous manner. Whatever happened to the bonnet that was once so tall and handsome, so elegant and bewitching? On returning from Hampstead, the Hackney Coachman demanded to be paid but Cassandra could not find any money in her pockets. The text at the top of page 19 tells us how Cassandra solves the problem: ‘She placed her bonnet on his head & ran away’. The bonnet is now on the head of the Frog who looks fed up. Note that the big rolling eyes of the Frog observe the small figure of Mouse Cassandra running away. Cassandra evidently ‘sold’ her lover, the bonnet, to save her life!

Figure 6.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 19.

If we compare this illustration with that on page 5 (Figure 6 vs. Figure 5), we see how capricious and self-centred Cassandra is in relation to the bonnet. On page 5, she looks up at the bonnet, entirely engrossed by its beauty; on page 19, she runs away, turning her back and abandoning it. On page 5, the height of the bonnet is emphasised—the newly finished bonnet is tall, proud, and attractive. Its height is further accentuated by the mannequin’s slender face. By contrast, on page 19, the flattened bonnet’s width is stressed. The Frog’s grim face, his set-apart legs and the Tortoise shell parallel the shape of the bonnet, stressing the fact that the bonnet is now crushed, battered, and in fact ruined. This is certainly an anticlimactic moment for the bonnet.

4. Depicting Satirical Drama in Jane Austen

How does an illustrator depict the climactic moment of a story? It will be helpful at this point to look at Joan Hassall’s illustration for the climactic moment in ‘Love and Freindship’.

Written in an epistolary style by fourteen-year-old Austen, ‘Love and Freindship’ satirises in an exaggerated manner the cult of sensibility while, at the same time, describing women’s power to subvert social restraint. Laura, the heroine and chief letter-writer of the story, boasts of her excessive sensibility. Living in ‘one of the most romantic parts of Vale of Uske [in Wales]’ (Austen 1975, p. 70), she meets Edward, the son of a Bedfordshire baronet. They fall in love at first sight and Laura’s father, though not a clergyman, conducts their marriage ceremony there and then. An avowed romantic, Edward refuses to live under obligation to his father, the baronet, and takes Laura to the house of his friend Augustus in Middlesex.

Augustus has stolen money from his despotic father and secretly married Sophia, another great admirer of the cult of sensibility. Sophia heartily welcomes the newly married couple and the two young wives immediately become bosom friends. Augustus, for his part, is overjoyed to see his old friend Edward and the two young men, calling each other ‘My Life! my Soul!’ and ‘My Angel!’ fly into each other’s arms. Observing such friendship between their husbands, Laura and Sophia are deeply moved and ‘fainted Alternately on a Sofa’. (Austen 1975, p. 77)

The two couples live in luxury until Augustus is arrested for debts and sentenced to imprisonment. Describing this misfortune, Laura writes: ‘Ah! what could we do but what we did! We sighed and fainted on the sofa’. (Austen 1975, p. 79)

Edward leaves for London to commiserate with his imprisoned friend, and Sophia and Laura decide to go to Scotland to live with Sophia’s cousin. The cousin treats them generously, yet Sophia has no qualms about stealing his money, saying that he must have obtained it by ill means. Sophia and Laura, moreover, instil the cousin’s daughter with such romantic ideas that the girl, who has been engaged to a sensible man, runs away with her good-for-nothing lover to Gretna-Green.

Sophia and Laura leave the residence of Sophia’s cousin and lament not having seen their husbands for a long time, when they hear a terrific crashing sound behind them. They discover an overturned phaeton which their husbands had been driving and the gentlemen thrown out onto the road. Shocked to find their husbands dead, Sophia faints while Laura has a hysterical fit: she shouts and raves in frantic manner for two hours.

Having remained too long on the wet grass, Sophia falls ill with pneumonia that proves fatal. Her dying message to Laura is:

‘Beware of swoons… A frenzy fit is not one quarter so pernicious; it is an exercise to the body and if not too violent, is I dare say conductive to health in its consequences—Run mad as often as you chuse [sic]; but do not faint—’.(Austen 1975, p. 90)

Hassall illustrates the scene after Sophia draws her last breath (Figure 7). On the left side of a long couch, we see Sophia dead, her head dropped on her left shoulder. The upper part of her body leans on the couch armrest, while her right arm dangles down. Sitting beside Sophia and overcome by her friend’s death, Laura howls and tears her hair as if she has gone mad.

Figure 7.

Joan Hassall’s illustration for ‘Love and Freindship’ (Austen 1975), p. 96. Courtesy of The Estate of Joan Hassall.

Sophia’s arms form a triangle that outlines the upper part of her body, while the lower part of her body forms an elongated triangle the top of which reaches the right end of the couch where we find her black shoes peeping out from the hem of her dress.

If the lower part of Sophia’s body makes a horizontal line, the upper part of Laura’s body emphasises a perpendicular line. In addition, her right hand touches the highest point of illustration, while the heel of her left shoe touches the lowest. A line that connects these two points parallels the perpendicular line of the upper part of her body as if to stress the fact that she is sitting erect and alive, in contrast to her dead friend whose lower part of the body lies flat on the couch.

The seat of the couch is covered with a minutely decorated floral cloth. The couch armrest is also decorated with small dots and fine lines. This heavy decoration makes the couch and armrest appear almost black, allowing the physical outlines of Laura and Sophia to stand out more clearly.

The geometric designs, such as triangles and perpendicular lines, enhance the contrast between the dead and the alive. Surprisingly, there is another geometric design to be found in the illustration. If we start from Sophia’s left shoe and follow down the outline of Laura’s skirt, turn upward as her right shoe directs, up along the right side of Sophia’s skirt, then over the upper part of Sophia’s hair, as well as Laura’s hair, we will come back to Sophia’s left shoe. This line encompasses the dead and the alive, all except for Sophia’s right arm, which makes her dangling arm seem even more grotesque.

Hassall’s wood carving is minutely executed.6 The parts of the woodblock that need to be carved with sharp knives and the parts that are to be left uncut are carefully planned and the directions closely followed, so that the geometric designs appear fine and clear. This exquisite work of art brings out the satirical drama that lies at the core of ‘Love and Freindship’.

5. ‘The Beautifull Cassandra’ as Satirical Drama

If the death of Sophia is the climax of ‘Love and Freindship’, the climax of ‘The beautifull Cassandra’ is Cassandra’s trip to Hampstead.

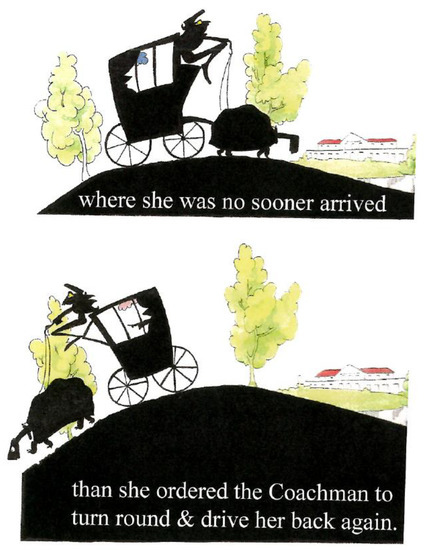

Austen describes the trip in a single sentence: ‘[Cassandra] next ascended a Hackney Coach and ordered it to Hampstead, where she was no sooner arrived than she ordered the Coachman to turn round & drive her back again.’ (Austen 2006, p. 55) McMaster divides the sentence into four scenes. We have already seen the first one: ‘[Cassandra] next ascended a Hackney Coach’ (Figure 4).

We will now look at the second section, pages 14 to 15. This is the highlight of The Beautifull Cassandra (Figure 8). A full double-page spread is devoted to illustrating the scene. Everything is large scale and in bright colours: green, yellow, brown, pink and red.

Figure 8.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), pp. 14–15.

The Frog Hackney Coachman is all happiness, making free use of his whip. The Tortoise, however, looks warily up at the whip. He cannot move fast enough. Sitting in the back of the huge coach, Mouse Cassandra, the despotic queen, gives directions to the Coachman with her foot! The text for this illustration simply says, ‘& ordered it to Hampstead’.

The daffodils and ribbon that decorate Cassandra’s bonnet fly out the coach window and are blown by the wind. The coach is evidently moving very fast despite going uphill. The City of London, depicted at the bottom of the left page, is already far behind. Beside the road there are beautiful flowers and a huge, colourful butterfly drinking nectar. But neither the Frog, nor the Tortoise, nor Cassandra pay any attention to the roadside. They are too eager to reach Hampstead where they are to see its famous fine views.7

The next page presents a dramatically darkened scene (Figure 9). Whatever happened to the coach, the Frog Coachman, and the Tortoise? They are all in silhouette and stand still, as if time has stopped. The background, on the other hand, is lightly coloured, sharpening the blackness of the silhouette. The size of the illustration has also been reduced to half a page.

Figure 9.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 16.

Let us examine the illustration at the top of the page. On the right-hand side of the background, we see a building with a red roof. This is Kenwood House; when ‘The beautifull Cassandra’ was composed, it was a residence of the Earl of Mansfield. Also in the background are huge trees, lawn, and a pond to represent Hampstead Heath. Cassandra has evidently arrived at the top of the hill.

If one stands at the top of the hill in Hampstead Heath today, one will find beautiful views all round. In fine weather, one can see the skyscrapers of north London. If, on the other hand, one prefers to take a walk, one will find large, ancient trees and ponds of various sizes. One can sit on the grass to enjoy the view at leisure. But Cassandra is evidently not interested in any view. She refuses to leave the coach. Why did she then order the coach to come all this way? The Frog Coachman, whose shape is delineated in silhouette, laments with his yellow-coloured eye. The Tortoise, who in silhouette looks like a rock, droops his head.

In the illustration at the bottom of the page, we read the last part of the sentence: ‘she ordered the Coachman to turn round & drive her back again’. The capricious, domineering mistress now wishes to be back in London. She directs the Coachman, this time not with her toe, but with her finger. Disheartened and exhausted, the Frog Coachman and the Tortoise cannot exert themselves. They go down the hill at the slowest possible pace.

In Austen’s time, it was very popular to have a likeness taken in silhouette.8 Having a portrait painted in oils was expensive and time-consuming, whereas a sitting for a silhouette took only a few minutes in a studio and one could purchase the finished profile, complete with a frame, for a reasonable price. We are familiar with the silhouettes of the different members of Austen’s family, which survive to the present day.

On page 16, McMaster presents delicate silhouettes to match Austen’s text. Children who read The Beautifull Cassandra may not know that silhouettes were popular in Austen’s age or that the building of Kenwood House was already there in her time. But they will immediately grasp the meaning of the transformation from colourful scene to black silhouettes. They will note the change of tone: a bright scene where everyone is climbing the hill at full speed with some happy prospect in view, versus the small, silhouetted images, where both the Frog and Tortoise appear dejected and with the coach descending the hill in slow motion like a funeral procession. The pictures speak for themselves. This is the success of McMaster’s illustrations.

We have seen Joan Hassall’s illustration of the climactic scene of ‘Love and Freindship’ and Juliet McMaster’s illustrations of the climactic scenes of ‘The beautifull Cassandra’. While Hassall concentrates on a dramatic moment, McMaster chooses a dramatic movement. She depicts the moment before and the moment after the climax. McMaster’s water-colour illustrations, together with the silhouettes, suit a dramatic narrative. Her illustrations are similar to comic strips and contemporary manga. Children may read the story by looking at the pictures.

6. ‘The Beautifull Cassandra’ as Prodigal Daughter?

Cassandra is a ‘prodigal daughter’ who comes home ‘unrepentant’. Twelve-year-old Austen in effect presents us with a comical female version of the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32). Without asking for her parents’ permission, Cassandra ‘takes out’ a family ‘fortune’—the bonnet her mother has made for the countess. In her pleasure-seeking drive to Hampstead, she ‘wastes’ this ‘fortune’.

In the Parable of the Prodigal Son, seeing his lost son return, the father ‘ran and fell on his neck and kissed him’. But Cassandra’s father expresses no such paternal love. Austen writes: ‘[Cassandra’s] father was of noble Birth, being the near relation of the Dutchess [sic] of ____’s Butler’. (Austen 2006, p. 54) He is proud simply because he is ‘related’ to ‘a butler of a duchess’. On page 23, McMaster emphasises the uselessness of this mouse father who lives entirely on the earnings of his wife, ‘a celebrated milliner’ (Figure 10). Attired in clothes ‘suitable’ to a mouse of ‘noble birth’, he haughtily cleans his teeth with a long toothpick. (Has he just finished his dinner?) He has no concern whatsoever for his ‘lost’ daughter, nor does he realise that, at this very moment, she has finally come home.

Figure 10.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 23.

McMaster sharply contrasts this image of Cassandra’s father with that of her mother. Cassandra’s mother has been working late, when—behold!—her daughter ‘who has been lost’ returns! With her arms wide open, she welcomes her daughter (Figure 11). The thimble which was on the mother’s finger a moment ago is thrown up in the air. Even her tail seems to express her joy! The text on the facing page 25 reads: ‘[Cassandra]… was pressed to her Mother’s bosom by that worthy Woman’. The prodigal daughter is welcomed home, not by her father but by her all-forgiving mother.

Figure 11.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 24.

Celebrating the occasion—for the lost daughter has now been found—the mother holds a party. Unlike the prodigal son in the parable, the prodigal daughter does not repent, nor does she make any confession. Look how Cassandra, the naughty child, behaves in McMaster’s final illustration (Figure 12). The spoilt child stretches herself out in an indolent manner on a reclining sofa, demanding a drink. The sofa is an upturned hat doubtlessly made by her mother. Cassandra not only throws her feet over the edge of the hat-sofa, but also takes off her shoes, proving how ill-mannered she is. Reviewing her seven-hour outing, she whispers to herself, ‘This is a day well spent’. Note the speech balloon, which McMaster uses to excellent effect.

Figure 12.

McMaster’s illustration for The Beautifull Cassandra (Austen 2021), p. 27.

7. Conclusions

We have examined various kinds of illustration that appear in Austen’s works. While Thomson emphasises the comedy in Austen’s work and Hassall depicts the satirical core of the story, McMaster enters into the spirit of twelve-year-old Austen’s writing and works in collaboration with, or more accurately, in conspiracy with her. McMaster reads into the text and illustrates the work in a juvenile spirit of hilarity and mischievousness. Moreover, she employs techniques that appeal to children. Her animal characters are particularly suited to depicting dramatic and hilarious actions of the story.

Twelve-year-old Austen obviously enjoyed writing the story of Cassandra, exaggerating her wilfulness and pleasure-loving egotism. McMaster’s illustrations capture this vigorous spirit using various contrasting strategies, such as colour spreads versus silhouettes and a double-page spread versus half a page, as well as by using unifying motifs such as hats and bonnets. McMaster celebrates Cassandra’s ingenuity in solving a problem with little loss. From this aspect, the story can be seen to epitomise the characteristics of juvenile literature with the protagonist going on a trip and returning home. Cassandra encounters a few difficulties but solves them with resourcefulness and is then welcomed home.

Cassandra represents young Austen’s love of vigour and freedom from restraint—freedom particularly from the artificial restraints of society. In The Beautifull Cassandra, McMaster stresses a positive interpretation, depicting Cassandra’s energy and mischievous unrestrained free spirit. In the present age, when we are so familiar with comic strips, films, TV screens, and many other kinds of visual imagery, illustrations may usurp words, but as McMaster’s illustrations prove, they can (and in this case do) collaborate with, support, and enhance the text. McMaster’s colourful illustrations invigorate the text, particularly because they incorporate animal characters with human expressions that children are now familiar with and usually love.

This picture book is enjoyable for children while being thought-provoking for students of Austen’s works. It allows Austen readers to be awed and engrossed by the story on a level with children, something a research paper cannot achieve. This is the intrinsic value of The Beautifull Cassandra, which is indeed a collaboration between the writer of 1788 and the editor-illustrator more than two centuries later, in 2021.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For the analysis of McMaster’s illustrations, I use the Juvenilia edition. For the history of this picture book, see McMaster’s ‘THE STORY OF THIS BOOK’ printed at the end of the book. McMaster’s illustrations were originally published in 1993 in a British Colombia publication. The 2021 Juvenilia edition is a reprint of this title. |

| 2 | Since McMaster’s illustrations first appeared in 1993, Princeton University Press has produced a 2018 version with artwork by Leon Steinmatz. |

| 3 | See, for example, (Gilbert and Gubar 1979) and the articles by John Halperin, Claudia L. Johnson, Patricia Meyer Spacks, and Juliet McMaster collected in (Grey 1989) |

| 4 | ‘a novel in twelve Chapters’ is the subtitle Austen gives to ‘The Beautifull Cassandra’. (Austen 2006) p. 53. |

| 5 | The pages of the picture book are not numbered. In this article, I will refer to the page on which the story begins as ‘page 1′ and paginate accordingly. |

| 6 | George Mackley’s ‘Engraving Technique’ in David Chambers, Joan Hassall: Engravings and Drawings (Mackley 1985) is helpful for understanding the complex technique involved in this art form. |

| 7 | In her article, ‘‘‘Here’s Looking at You, Kid”: The Visual in Jane Austen’s Juvenilia’, McMaster explains how she decided on Cassandra’s progress ‘from left to right’: ‘For continuity I decided on an outward/homeward progress. As Cassandra launches on her adventures, she progresses from left to right, like the printed line. The coach heading up to Hampstead heads from the left of the page towards the right. At turn-around time the action moves homewards from right to left’ (McMaster 2020). |

| 8 | Peggy Hickman writes: ‘Jane Austen lived in an age when the easiest way to obtain a likeness of oneself was to have a silhouette cut or painted’. Hickman, ‘Jane Austen’s Family in Silhouette’ in Shades from Jane Austen, ed. by Honoria D. Marsh (Hickman 1975), p. xiii. |

References

- Austen, Jane. 1975. Shorter Works. London: The Folio Society. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, Jane. 2005. Pride and Prejudice. Illustrated by Hugh Thomson. New York: Dover Publications. First published 1894. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, Jane. 2006. Juvenilia. Edited by Peter Sabor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, Jane. 2021. The Beautifull Cassandra. Illustrations and Afterwords by Juliet McMaster. Sydney: Juvenilia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Sandra M., and Susan Gubar. 1979. Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 113–19. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, J. David, ed. 1989. Jane Austen’s Beginnings: The Juvenilia and ‘Lady Susan’. Ann Arbor and London: UMI Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, Peggy. 1975. Silhouettes of Jane Austen’s Family. In Shades from Jane Austen. Authored and Edited by Honoria D. Marsh. London: Parry Jackman, pp. xiii–xxii. [Google Scholar]

- Hisamori, Kazuko. 2017. ‘The Beautifull Cassandra Kou: Juliet McMaster no Sashi-e wa Jane Austen no Shouhin wo dou Tora-eruka’ (1). [‘Reading The Beautifull Cassandra: How Juliet McMaster interprets a Piece of Juvenilia of Jane Austen’ (1)]. Jein Ōsutin Kenkyu [The Journal of the Jane Austen Society of Japan], 31–45. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Hisamori, Kazuko. 2021. ‘The Beautifull Cassandra Kou: Juliet McMaster no Sashi-e wa Jane Austen no Shouhin wo dou Tora-eruka’ (2). [‘Reading The Beautifull Cassandra: How Juliet McMaster interprets a Piece of Juvenilia of Jane Austen’ (2)]. Jein Ōsutin Kenkyu [The Journal of the Jane Austen Society of Japan], 25–46. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Le Faye, Deirdre. 1989. Jane Austen: A Family Record. London: The British Library. [Google Scholar]

- Mackley, George. 1985. Engraving Technique. In Joan Hassall: Engravings and Drawings. Edited by David Chambers. Pinner: Private Libraries Association, pp. xiii–xxi. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster, Juliet. 2020. “Here’s Looking at You, Kid!”: The Visual in Jane Austen’s Juvenilia. Persuasions On-Line 41. Available online: https://jasna.org/publications-2/persuasions-online/vol-41-no-1/mcmaster/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Sabor, Peter, ed. 2006. Introduction. In Juvenilia. Authored by Jane Austen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. xxiii–lxvii. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).