Abstract

Children occupy a peripheral position in the novels of Jane Austen, with the result that they have received little critical attention. This article proposes that, despite their marginal status, children play a significant role in Austen’s work as agents of disruption, whose presence is frequently signified by the noise they make. It is through their interventions that Austen dramatizes a wider crisis in the capacity of conversation to improve, educate, and forge meaningful connections between individuals. The significance of Austen’s representations of children can be grasped more fully by reading Austen in relation to her contemporaries, namely Maria Edgeworth and Hannah More. While these authors view children as the embodiment of Enlightenment hopes and Revolutionary fears, Austen avoids such polemical representations. Rather than rational actors participating within a culture of improving conversation, Austen’s children are defined by their inarticulate voices and disruptive tendencies. Ultimately, however, it is through their inarticulacy that Austen expresses her doubts about the status of conversation as a site of enlightened exchange.

1. Introduction

Throughout her letters, Jane Austen writes about children with a blend of affection and amusement. This is particularly the case when she turns to the subject of her many nieces and nephews. In addition to detailing their developing personalities, Austen sometimes permits the children’s voices to come to the fore of her correspondence. For instance, writing to her sister Cassandra in 1799, Austen relays messages from Edward and Fanny, aged five and six, respectively:

Fanny desires her Love to You, her Love to Grandpapa, her love to Anna, & her Love to Hannah;—the latter particularly is to be remembered.—Edw:d, to Aunt James & Uncle James, & he hopes all your Turkies & Ducks & Chicken & Guinea Fowls are very well—(Austen 1995, p. 45)

A week later, Austen writes again, transcribing short messages that the children have dictated to their aunt Cassandra. Once more, her letter captures the children’s unpredictable associative logic, as evinced in the note from Edward:

The direct expression of the children’s voices alongside Austen’s own provides a literal demonstration of what Kathryn Sutherland calls the ‘the multivocality of [Austen’s] letters’, by which they become a communal space that sustains family bonds across geographical distance (Sutherland 2009, p. 20).My dear Aunt Cassandra—I hope you are very well. Grandmama hopes the white Turkey lays, & that you have eat up the black one.—We like Gooseberry Pye & Gooseberry pudding very much.—Is that the same Chaffinches Nest that we saw before we went away?(Austen 1995, p. 48)

The inclusive multivocality of Austen’s letters presents a striking contrast to the way that she writes about children in her fiction. While Juliet McMaster suggests that Austen’s novels are ‘exact, specific, and sympathetic’ in their observation of children, it is notable that we rarely encounter the kind of childish voices that Austen transcribes with such devoted care in her letters to Cassandra (McMaster 2010). As Marshall Brown notes in his discussion of Emma, the novel’s child characters ‘generally remain offstage’; they are overlooked and stranded at the margins of the narrative (Brown 2014, p. 7). While there are a small number of exceptions, throughout Austen’s work children are generally either silent presences or noisy, querulous individuals, whose utterances rarely find expression in direct speech. The articulate voices found in Austen’s letters are replaced by children making a ‘great deal of noise’, expressing themselves in ‘violent screams’, and by domestic scenes in which ‘chattering’ girls compete with ‘riotous boys,’ drowning out any attempt at conversation (Austen 2017, pp. 4, 99; 2004, pp. 109–10).

It is the antagonistic relationship between conversation and children’s inarticulate voices that I explore in this article. Focusing on Sense and Sensibility and Persuasion, alongside works by Maria Edgeworth and Hannah More, I suggest that Austen’s deliberate positioning of children as disruptive, rather than conducive, to conversation demonstrates her distinctively sceptical perspective on the civilising and educative power of sociability. Several critics have discussed the concept of conversation in relation to Austen. To varying degrees, their work demonstrates how conversation was imperilled in her writing. Bharat Tandon, for instance, attributes the ‘problems of communication in Austen’s novels’ to a concurrent crisis in the ‘culture of “polite” conversation’, while Jon Mee observes that Austen’s fiction marks the endpoint of a model of eighteenth-century sociability that had always been precarious: ‘a place of contention as much as a place of dialogue’ (Tandon 2003, p. 3; Mee 2011, p. 32). The idea that conversational culture underwent a transformation in Austen’s lifetime is also central to Patricia Howell Michaelson’s Speaking Volumes. Michaelson argues that the didactic function of conversation manuals in the eighteenth century was taken up by novels in the early nineteenth century, including those of Austen (see Chapter five of Howell Michaelson 2002). For Harriet Guest, meanwhile, Austen’s work responds to shifts in conversational culture by presenting a carefully calibrated relationship between ‘the difficulties of direct conversational exchange’ and the connections formed by ‘imaginative sympathy’ (Guest 2013, p. 173). None of these critics, however, point to the role of children in dramatizing, and often exacerbating, conversational confusion.

Indeed, Austen’s fictional rendering of children is seldom addressed directly. Before exploring this topic further, it is worth considering what constituted a child in Austen’s lifetime. As Anja Müller observes, the notion of childhood itself is ‘a cultural construct which (adult) societies actively construe in various discourses […] for different purposes’ (Müller 2006, p. 3). These competing constructions meant that, within the eighteenth century, childhood was a remarkably broad concept, one that ‘encompassed infancy, boyhood and girlhood, adolescence, and overlapped with adulthood’ (Grenby 2011, p. 11). Indeed, as Müller and others have noted, the state of childhood potentially extended up until the age of twenty-one.1 Obviously, such a flexible definition would mean that most of Jane Austen’s heroines can, and perhaps should, be classed as children. However, my concern in this essay is with a younger childhood: with characters who show no signs of embarking on the process of emotional and moral maturation that distinguishes Austen’s protagonists.2 For that reason, I do not discuss heroines such as Fanny Price and Catherine Morland, whose early lives are presented as a precursor to their subsequent development.

Previous discussions of children in Austen’s work include David Selwyn’s comprehensive Jane Austen and Children and Neil Cocks’s The Peripheral Child in Nineteenth-Century Literature. While Selwyn’s aim is to draw attention to Austen’s ‘use of children’ for the purposes of comedy and plot progression, Cocks pursues a psychoanalytically informed approach, in which the figure of the child ‘resists’ the ‘stable and marginal position’ it is assigned (Selwyn 2010, p. 3; Cocks 2014, p. 24). I share Cocks’s sense of the significance of the disruptive child in Austen’s work, but not his methodology. Instead, I am concerned with children’s impact on the soundscapes of Austen’s novels, and with the way in which their inarticulate interventions allow Austen to comment on the period’s conversational culture. The significance of sound and hearing in Austen’s fiction has been discussed by critics including Adela Pinch and, more recently, Kate Nesbit (see Pinch 1996; Nesbit 2015). The inarticulacy and volume of children in Austen’s work can also be profitably discussed in relation to contemporary theorisations of ‘noise’. As Kevin Stevens notes, to identify a sound as ‘noise’ is to signal its disruptive tendency: as both ‘sonic and social dissonance’, noise is diametrically opposed to the civilizing aspirations of polite conversation (Stevens 2018). In a similar vein, Jeff Nunokawa refers to noise as not just the ‘absence’, but the ‘degradation of speech’, further suggesting its antagonism towards rational discourse (Nunokawa 2005, p. 16). Considering Austen’s noisy children in these terms demonstrates a key distinction between her work and that of her contemporaries. While authors such as Maria Edgeworth are guided by an Enlightenment ideal in which children participate within the conversational life of their family, Austen offers a far more sceptical take on the possibility of achieving such familial harmony. Her representation of children, I suggest, can be taken as an example of the ‘severe realism’ that tempers her ‘faith in improvement’ and, as such, is indicative of her complex relationship with the progressivism of Enlightenment thought more broadly (Knox-Shaw 2004, p. 254).

2. Disrupted Conversation in Sense and Sensibility

As Jon Mee observes, although Austen is often ‘regarded as the doyenne of conversation in the English novel’, her plots pivot around failures of communication (Mee 2011, p. 201). Rather than connecting characters, conversations typically emphasise the distance between them. Although Mee does not consider the role of children in disrupting conversation, their presence is frequently implicated within the difficulty of realising what he calls the ‘[v]alues of easy circulation and frank exchange’ (Mee 2011, p. 201). Of all the households encountered in Austen’s novels, that of Sir John and Lady Middleton in Sense and Sensibility promises the least in the way of conversation. Whether at Barton Park or Barton Cottage, the Middletons’ idea of sociability affords ‘very little leisure […] for general chat, and none at all for particular discourse’ (p. 106). In place of the intellectual fulfilment promised by conversation, Sir John prioritises the more physical pleasures of ‘eating, drinking, and laughing together’ and the playing of any game ‘that was sufficiently noisy’ (p. 106). While these sociable sounds are associated with the amiable hospitality of Sir John, a different kind of noise is required to rouse his wife from her state of ‘cold insipidity’ (p. 27): that of her children. This is evident when Austen describes the second meeting between the Middletons and the Dashwoods:

As Selwyn notes, in Austen’s work the misbehaviour of children ‘reveal[s] the deficiencies of the parents rather than the wrongdoings of the children’. In this instance, Selwyn suggests, it is Lady Middleton’s ‘willingness to sacrifice everybody’s comfort’ to that of her children that is offered up for critique (Selwyn 2010, pp. 102, 108). However, it is not only ‘comfort’ that is sacrificed: conversation is arguably the main casualty of the ‘noisy’ children’s presence. The demands they make on their mother, signalled by the damage they inflict on her clothes, are mirrored by the demands they make on the conversation, which turns inwards until it is orientated around the children alone. Eliciting conversation that relates only ‘to themselves’, the presence of the children limits the two families’ interactions, acting as a barrier to meaningful exchange.Lady Middleton seemed to be roused to enjoyment only by the entrance of her four noisy children after dinner, who pulled her about, tore her clothes, and put an end to every kind of discourse except what related to themselves.(p. 27)

Even when children are silent, their mere presence diverts conversation from meaningful discussion. When the Dashwood women first arrive at Barton Cottage, they are visited by Sir John and Lady Middleton who are accompanied by their eldest child. Austen offers a contrast between the ‘frankness and warmth’ (p. 23) of Sir John and the chilly formality of his wife, who ‘was reserved, cold, and had nothing to say for herself beyond the most common-place inquiry or remark’ (p. 23). Despite this, Austen notes that:

This scene establishes a pattern that recurs in the novel, in which awkward silences are avoided by the presence of children who provide a ready source of conversational capital. This dynamic is encapsulated in the narrator’s ironic prescription: ‘On every formal visit a child ought to be of the party, by way of provision for discourse’ (p. 24). That ‘discourse’, however, is a pale imitation of the ‘easy circulation and frank exchange’ that comprises the conversational ideal (Mee 2011, p. 201). Indeed, the presence of a child has the potential to confer obligations on the company: a social script must be followed, as Austen implies when noting that the Dashwoods ‘had to inquire his name and age, admire his beauty, and ask him questions’ (my italics). Children may provide a reliable topic of discussion, but the conversation they initiate can prove both constrained and coercive.Conversation […] was not wanted, for Sir John was very chatty and Lady Middleton had taken the wise precaution of bringing with her their eldest child, a fine little boy about six years old, by which means there was one subject always to be recurred to by the ladies in case of extremity, for they had to inquire his name and age, admire his beauty, and ask him questions which his mother answered for him, while he hung about her and held down his head, to the great surprise of her ladyship, who wondered at his being so shy before company as he could make noise enough at home.(pp. 23–24)

The degradation of conversation that occurs around children is similarly apparent during a gathering at the house of John Dashwood, where it is inflected by issues of gender. When the ladies retire to the drawing-room, they find little to discuss. ‘[T]he gentlemen’, Austen writes, ‘had supplied the discourse with some variety’ (p. 175) but, left to their own devices, ‘one subject only engaged the ladies till coffee came in, which was the comparative heights of Harry Dashwood, and Lady Middleton’s second son, William’ (pp. 175–76). The fact that only one of the children is present makes the task of discovering who is the tallest impossible, but it does allow ‘every body […] to be equally positive in their opinion, and to repeat it over and over again as often as they liked’ (p. 176). As Guest suggests, the lack of ‘affective exchanges’ is indicative of the cold-hearted materialism of Fanny Dashwood and Lady Middleton (Guest 2013, p. 168). However, these examples also reveal the contradictory way in which children simultaneously elicit and obstruct conversation in Sense and Sensibility. While they provide a convenient object of conversation, the discourse they prompt cannot raise itself beyond the immediate physical presence of the children. Willingly or not, within Sense and Sensibility, children absorb attention and reorientate the discussion around themselves.

Tandon observes that Austen ‘[grew] up at the end of a century in which much had been hoped for and feared from the practices of talk and manners’ (Tandon 2003, p. 3). The notion that a ‘culture of politeness’ emerged as a means of ameliorating the legacy of the political and religious crises of the seventeenth century is well established (Tandon 2003, p. 5).3 As J.G.A. Pocock writes, politeness became ‘an active civilizing agent’, providing ‘a highly serious practical morality’ and a means of harmonising competing social interests (Pocock 1985, p. 236). This model of politeness is captured by Adam Smith in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, where the ‘pleasure of conversation and society’ is attributed to ‘a certain correspondence of sentiments and opinions’ and a ‘harmony of minds, which like so many musical instruments coincide and keep time with one another’ (Smith 1976, p. 337). A similar vision is conjured by Austen’s favourite poet, William Cowper, for whom ‘the communication of one’s ideas’ provides a form of ‘delight […] that not only proves us to be creatures intended for social life, but more than any thing else perhaps, fits us for it’ (Cowper 1979–1986, I, 543–44). As Michèle Cohen has noted, this harmonious conversational culture was not limited to adults: children were also ‘expected to participate actively in familial, social gatherings and conversations’. Not only did this enable them to learn about a variety of topics, but their involvement also taught them ‘about sociality and politeness’, which were ‘integral aspects of children’s education in the home’ (Cohen 2009, p. 101).4

The conversationally fluent children discussed by Cohen are a long way from the disruptive children of Sense and Sensibility. Indeed, the frequent references to the noise they make is in stark opposition to the concordant musicality suggested by Smith’s ‘harmony of minds’. The Middleton children’s fraught relationship with conversation could be considered a symptom of the growing uncertainty that Tandon suggests surrounded the culture of politeness in Austen’s lifetime. However, if Austen relays this uncertainty through the actions of her disruptive child characters, many of her contemporaries continued to depict children actively participating within a culture of enlightened conversation. A particularly instructive contrast can be drawn between Austen’s work and that of Maria Edgeworth.

3. Maria Edgeworth and the ‘Trifling, but Genuine Conversations of Children’

Edgeworth frequently suggests that children’s participation in familiar conversation is of benefit, both to them and to society. The political resonance of the ‘domestic idyll of participatory openness’ that recurs in her writing has been profitably discussed by a range of critics (Myers 1999, p. 237). For Mitzi Myers, Edgeworth’s mode of ‘reformist pedagogy’, which envisages children engaging in equal and open exchanges with adults, is a model of a more equitable and enlightened society (Myers 1999, p. 237). Susan Manly captures something of the egalitarianism to which Myers refers when she notes that Edgeworth understands ‘conversation between adults and children as a genuine dialogue, one from which both parties can learn’ (Manly 2007, p. 140).

The association between children and conversational culture is attested to by the vast number of children’s books that were written in the form of dialogues by writers such as Anna Letitia Barbauld, Charlotte Smith, Sarah Trimmer, and Priscilla Wakefield. These works were often informed by the twin influences of John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose writings provided ‘a common reference point for educational writers and a set of implicit guidelines for writers of children’s books’ in the eighteenth century (Ferguson 2017, p. 187). As Aileen Fyfe notes, these texts depicted dialogues in which fictional children learn from fictional adults, with the intention of instructing real child readers (Fyfe 2000, p. 468). Such works frequently draw attention to the transformative power of conversation and present children as possessing the ability ‘to connect facts, to think for themselves, and to produce rational conclusions’ (Fyfe 2000, p. 469).5 This is the case in Edgeworth’s works, whose commitment to conversation is apparent in both her fictional and her pedagogical writings. In Practical Education, from 1798, she suggests that conversation plays an important auxiliary role in children’s education by filling the intervals between specifically designed educational ‘occupations’. In ‘a large and literary family’, she writes, conversation ‘will create in [children’s] minds a desire for knowledge […] and if they are encouraged to take a reasonable share in conversation, they will acquire the habit of listening to every thing that others say’ (Edgeworth 1798, II, 581). Conversation forms an edifying intellectual backdrop, stimulating children’s curiosity and fortifying their attention. The kind of active listening that makes conversation an act of amicable and educative exchange is a long way from the destructive Middleton children, who tear at their mother’s clothes in Sense and Sensibility.

While the presence of Lady Middleton’s children obstructs the current of conversation, making ‘every kind of discourse except what related to themselves’ impossible (p. 26), Edgeworth’s ambition is for conversation to flow unimpeded around and through children: a principle depicted in her 1801 novel, Belinda. There, the conversational mode described in Practical Education finds expression in the home of the Percival family, where the children are the mirror-image of their virtuous parents:

This domestic scene captures something resembling the ‘free communication of sentiments and opinions’ that comprises the conversational ideal in Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (Smith 1976, p. 337). Edgeworth’s reference to children being ‘treated […] as reasonable creatures’ also recalls John Locke’s influential Some Thoughts Concerning Education, in which Locke proposes that children should be ‘reason[ed] with’ and ‘treated as rational creatures, sooner than is imagined’ (Locke 1996, p. 58). Under the influence of this form of enlightened conversational education, the Percivals’ home comes to resemble a public forum in the Habermasian sense of a ‘training ground’ for ‘critical public reflection’: one in which children are imagined to be active participants (Habermas 1989, p. 29).In conversation, every person expressed without constraint their wishes and opinions; and wherever these differed, reason and the general good were the standards to which they appealed. The elder and younger part of the family were not separated from each other; even the youngest child in the house seemed to form part of the society, to have some share and interest in the general occupations or amusements. The children were treated neither as slaves nor as playthings, but as reasonable creatures.(Edgeworth 1994, pp. 215–16)

Acknowledging the exemplary nature of this scene, Edgeworth’s narrator notes that some may ‘suppose the picture to be visionary and romantic’ and yet, she maintains, ‘it is drawn from truth and real life’ (p. 216). Her insistence on the fidelity of her representation of children’s conversation is attested to in the appendix to Practical Education, which includes transcriptions of what she calls the ‘trifling, but genuine conversations of children and parents’ (Edgeworth 1798, II, 734). As in Austen’s letters, these representations of children’s voices bear the stamp of authenticity. Edgeworth records children ‘considering their own words and those of others’ as they engage them in conversations about seemingly mundane domestic phenomena (Manly 2007, p. 138). Topics such as the relative boiling points of water and chocolate, the material composition of a toothpick, and the cause of the wind provide ample opportunities to introduce children to scientific concepts and principles. At times, these conversations grow strained. The father’s question, ‘can you tell me what is meant by a body’s falling’, puzzles the seven-year-old S——, who (quite reasonably) requires clarification over the meaning of ‘a body’ in this context. Likewise, when that conversation explores how it is known that the earth is round, the father struggles to find language adequate to explain the matter to the child:

Such moments demonstrate that conversational education does not always entail the smooth transmission of knowledge from adult to child. Strikingly, the failure of both the adult’s explanatory power and the child’s comprehension is manifested as a linguistic breakdown: the long dash that follows the father’s reference to ‘the shadow’ is indicative of the distance between the understandings of the adult and the child. Nevertheless, for Edgeworth such lacunae are an object of interest that speaks to her enlightenment ambitions. By attending to both the successes and the failures of children’s ‘trifling’ conversations, Edgeworth is able to trace what she refers to as ‘the progress of the mind in childhood’ (II, 733–34). From her pedagogical perspective, even disrupted conversations possess value.Father. ‘What shape do you think the earth is?’S——. ‘Round’Father. ‘Why do you think it is round?’S——. ‘Because I have heard a great many people say so’Father. ‘The shadow.—It is so difficult to explain to you, my dear, why we think that the earth is round, that I will not attempt it yet.’(II, 746)

Edgeworth’s philosophical perspective is indicative of her ambition to raise children as what Nicole M. Wright terms ‘agents of reason’ (Wright 2012, p. 512). These innately curious children are active participants in domestic conversations and form the articulate mirror-image of the Middleton children, who either interrupt conversation or become its subject. Indeed, Edgeworth frequently argues against making children objects of display, writing that ‘Children should never be introduced for the amusement of the circle’ (I, 147). Likewise, she cautions against resorting to children to stimulate conversational activity: ‘Children who are thought to be clever are often produced to entertain company; they fill up the time, and relieve the circle from that embarrassing silence, which proceeds from the having nothing to say’ (I, 138). Where Austen resorts to characteristic irony when suggesting that children should be present ‘[o]n every formal visit […] by way of provision for discourse’ (p. 24), Edgeworth explores the negative consequences of using children as conversational fodder. Acknowledging that their naïve observations may be entertaining—particularly when they ‘blurt out those simple truths which politeness conceals’—she observes that such artlessness outstays its welcome as children grow older: ‘boys who have been the delight of the whole house at seven or eight years old, for the smart things they could say, sink into stupidity and despondency at thirteen or fourteen’ (I, 138).

A recurring message in Practical Education concerns the harm that is done to children should they be praised to excess by friends and relatives. Parents, Edgeworth states, should use ‘cool reserve’ to ‘discourage […] visitors from flattering their children’ (I, 147). Austen displays a similar understanding of the dynamics of flattery in the form of the Miss Steeles in Sense and Sensibility. Austen presents the Steele sisters’ calculated interactions with Lady Middleton’s children, with whom ‘they were in continual raptures, extolling their beauty, courting their notice, and humouring all their whims’ (p. 90). Lady Middleton emphatically lacks the ‘cool reserve’ that Edgeworth suggests parents should adopt in instances of excessive praise. As Austen informs her readers, ‘a fond mother […] in pursuit of praise for her children, [is] the most rapacious of human beings’ (p. 91). Accordingly, Lady Middleton watches ‘with maternal complacency’ as her children set about further acts of minor violence:

[Lady Middleton] saw [the Steeles’] sashes untied, their hair pulled about their ears, their work-bags searched, and their knives and scissors stolen away, and felt no doubt of its being a reciprocal enjoyment. […]

‘John is in such spirits today!’ said she, on his taking Miss Steeles’s pocket handkerchief, and throwing it out of the window—‘He is full of monkey tricks.’

This scene is filtered through Elinor’s shrewd perception. While she is keenly aware of the efforts the Steeles are undertaking to ‘[make] themselves agreeable to Lady Middleton’, Lady Middleton herself remains oblivious to the deeper game at work, seeing only mutual pleasure (p. 90). If, as Claudia Johnson suggests, Lucy ‘play[s] the sycophant to wealth and power’, in this instance that role requires her to bear stoically the rough treatment meted out by the Middleton children (Johnson 1988, p. 50). Indeed, there is some irony that Lucy Steele, whose name ‘calls attention to her as a thief (of husbands and fortunes)’, is here stolen from by the rapacious children (Heydt-Stevenson 2005, p. 49). Once more, children are presented as agents of disruption who threaten to undermine, rather than contribute to, domestic harmony. Their focus is on disturbing the props of polite femininity, attacking first the Steeles’ clothing and hair before setting about the accoutrements of feminine industriousness: the women’s knives, scissors and work-bags. Likewise, the disposal of Miss Steele’s handkerchief through the window punctures the picture of domestic containment, upsetting the border between inner and outer, just as John’s ‘monkey tricks’ impinge upon the border between rational humanity and irrational animality.And soon afterwards, on the second boy’s violently pinching one of the same lady’s fingers, she fondly observed, ‘How playful William is!’(p. 91)

This breaching of borders is maintained by William’s ‘pinching one of [Miss Steele’s] fingers’: an action that recalls a more sensational moment in Austen’s juvenile tale ‘Henry and Eliza’, in which Eliza’s children signal their hunger by ‘biting off two of her fingers’ (Austen 2006, p. 43). The scene in Sense and Sensibility may dispense with the hyperbole of the juvenilia, but it retains an unsettling air: in both cases, children resort to the visceral language of the body rather than the verbal articulation of their desires. The cannibalistic actions of the children in ‘Henry and Eliza’ dramatize the demands that children make upon the maternal body; in a similar way, the Middleton children make exorbitant demands on the Steele sisters. Their relationship with the children is, as Jillian Heydt-Stevenson observes, one of work. In addition to playing with the children, Lucy is committed to making a filigree basket for the three-year-old Annamaria Middleton: if she is to ingratiate herself with Lady Middleton, she must ‘[earn] her keep’ (Heydt-Stevenson 2005, p. 46). Far from the egalitarian relationship between adults and children imagined by Edgeworth, the Middleton children exert a despotic influence that exposes the inequality between themselves and the Miss Steeles. In this respect, Austen echoes a fundamental lesson of Rousseau’s Emile, which insists that a child who ‘[has] everything he wants’ and who is ‘used to find[ing] everything give way to [him]’ will acquire a ‘love of power’ and become ‘a tyrant’ (Rousseau 1950, pp. 34, 51–52).6

Attending to the representation of children in Sense and Sensibility reveals the underlying power dynamics of domestic life; yet Austen makes no explicit connection between children’s behaviour and the wider political world. By contrast, Edgeworth frequently refers to the social and political implications of involving children in the intellectual life of their family. As Manly notes, her work imagines children to be ‘future citizens-in-the-making’, while Myers labels her ambitions in Practical Education both ‘radical’ and ‘revolutionary’ (Manly 2007, p. 146; Myers 1999, p. 237). However, Austen’s turning away from Edgeworthian optimism should not be mistaken for a counter-revolutionary conservatism. This point is evident when Austen’s work is read in relation to that of Hannah More.7

4. Hannah More and the Revolutionary Spirit

Austen was no fan of More’s 1808 novel, Coelebs in Search of a Wife. When Cassandra urged her to read it, she replied sceptically, while mistaking the novel’s name: ‘You have by no means raised my curiosity after Caleb;—My disinclination for it before was affected, but now it is real’ (Austen 1995, pp. 169–70). More’s novel follows its protagonist, Charles (the self-styled ‘Coelebs’ of the title), as he visits a number of households in search of a woman suitable to marry. As its modern editor notes, ‘[t]he scene in Coelebs is one of conversation’, and it is through the novel’s scenes of sociability that More enacts various ideological debates and laments the decline of Christian morality (Demers 2007, p. 10). Of all the families that Charles encounters, the Stanleys most obviously represent More’s ideal. Their virtuous qualities are manifested in their children, whose appearance charms Charles:

Focalised through Charles’s first-person narration, the Stanley children present an idyllic picture. As in Practical Education, these children are active participants in their parents’ social life. They are permitted to mix with visitors to the family home because, as their mother observes, ‘company amuses, improves, and polishes them’ (p. 118).When we were summoned to the drawing-room, I was delighted to see four beautiful children, fresh as health and gay as youth could make them, busily engaged with the ladies. One was romping; another singing; a third was showing some drawings of birds, the natural history of which she seemed to understand; a fourth had spread a dissected map on the carpet, and had pulled down her eldest sister on the floor to show her Copenhagen. It was an animating scene.(More 2007, pp. 117–18)

While the Stanleys are a model family, More details other households in which the management of children ranges from benign overindulgence to harmful neglect. The former is represented by the Belfield family: warm and hospitable, their household becomes ‘a pleasant kind of home’ to Charles (p. 79). Nevertheless, the scenes involving their children anticipate the turbulence caused by the young Middletons in Sense and Sensibility. The Belfield children are first introduced when they are admitted to the dining room after dinner:

Like the Middleton children in Sense and Sensibility, the tumultuous entrance of the young Belfields is both a physical and a sonic invasion that draws meaningful conversation to a close. More’s portrait of the children is at once sentimental and satirical: for all that they are ‘lovely, fresh, [and] gay’, they are also ‘noisy’ and ‘violent’. This duality culminates in the label ‘pretty barbarians’. The terminology is apt, considering that a ‘barbarian’ is classically defined as one who lives outside of, and represents a threat to, the Roman empire. In More’s novel, the ‘barbarian’ children encroach not on the civilisation of Rome, but on the civilisation of the modern dining room. Indeed, the Belfields’ dining room is not only a place of enlightened conversation, but a site that facilitates the dissemination and domestication of imperial knowledge. Before the children’s interruption, Charles had been engaged in conversation with ‘an ingenious gentleman’ (p. 60) who had spent a year in Egypt. His account of his travels is curtailed when a child knocks over a glass of wine, resulting in a scene of ‘agitation, and distress, and disturbance, and confusion’ (p. 62). Although order is restored after ‘the poor little culprit was dismissed’, Charles laments that ‘the thread of conversation had been so frequently broken, that I despaired of seeing it tied together again’ (p. 62). In place of the ‘catacombs, pyramids, and serpent’ of Egypt, Charles ruefully ‘content[s] [himself] with a little desultory chat with [his] next neighbour’ (p. 62). The expansive, cosmopolitan conversation that Charles had eagerly anticipated is contracted and replaced with shallow and fragmentary ‘chat’.[T]he mahogany folding doors [opened], and in at once, struggling who should be first, rushed half a dozen children, lovely, fresh, gay, and noisy. This sudden and violent irruption of the pretty barbarians necessarily caused a total interruption of conversation.(p. 61)

As in Sense and Sensibility, the presence of children is accompanied by a narrowing of discourse and the termination of meaningful exchange. Unlike Austen, however, More is eager to reform this state of affairs. Over the course of the novel, Sir John and Lady Belfield come to realise the deficiencies of their children’s behaviour and strive, instead, to emulate the practices of the Stanley family. Lady Belfield becomes ‘desirous of improving her own too relaxed domestic system’ and aims ‘to acquire firmness, without any diminution of fondness’ in her interactions with her children (p. 209). With the exception of Mansfield Park, which concludes with Sir Thomas Bertram regretting the ‘grievous mismanagement’ of his daughters’ education, Austen seldom depicts flawed parents becoming aware of, and taking responsibility for, their failures as carers (Austen 2003, p. 363).8 Instead, parental ineptitude typically provides a source of comedy that the reader is invited to observe with detached amusement. Such complacency is not an option for More, who possesses a more urgently politicised view of the family unit. This is most apparent in her depiction of the Reynolds children. Charles’s first encounter with them forms a telling contrast to the serene tableau of the Stanley household:

While the Stanley children engage in productive pursuits, the young Reynolds are intent on the destruction of their lavish playthings. More compounds the disorder of this scene with her allusion to John Milton’s Paradise Lost: there, it is the fallen angels who, having rebelled against God and been exiled from heaven, ‘apart sat on a hill retired’ (Milton 2004, II, l. 557). Unlike Milton’s angels, the children’s fallen state is not attributable to rebellion, but to the fact that they have no authority to rebel against; their undesirable behaviour is said to derive from their mother who, Charles is told, ‘is not a bad, though an ignorant woman’. Having been ‘harshly treated by her own parents’, Mrs Reynolds has veered to the opposite extreme, neglecting all forms of discipline when raising her own children (p. 207).Before the rich silk chairs knelt two of the [Reynolds] children, in the act of demolishing their fine painted play-things; ‘others apart sat on the floor retired,’ and more deliberately employed in picking to pieces their little gaudy works of art. A pretty girl, who had a beautiful wax doll on her lap, almost as big as herself, was pulling out its eyes, that she might see how they were put in.(p. 210)

In addition to linking poor parenting with childish misbehaviour, More suggests that domestic disorder is a symptom of wider political disorder. Shortly before their encounter with the Reynolds children, Mrs Stanley reflects:

The ‘new school of philosophy and politics’ to which Mrs Stanley refers is that of Revolutionary France. While Coelebs was published twenty years after the outbreak of the French Revolution, at the time of its publication Britain had been at war with France for most of the last fifteen years. More was gripped by a longstanding fear of ‘the invasion of French ideas’; almost a decade earlier, she had expressed identical sentiments in her Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education (Cleere 2007, p. 14). There, too, More refers to the ‘revolutionary spirit’ that prevails ‘in families’, and observes that ‘domestic manners’ are ‘tinctured with the hue of public principles’ (More 1799, I, 135). For More, there is no secure boundary between the private realm of the family home and the public sphere of war, politics and revolution. Indeed, while Jon Mee has suggested that Coelebs is primarily concerned with ‘an internal enemy in the shape of moral complacency and religious laxity among the elite’, Eileen Cleere observes that the novel is shaped by a variety of external social ills, including ‘the destabilizing effects of war, poverty, starvation, and violence’ (Mee 2011, p. 225; Cleere 2007, p. 5). More’s attention to children conflates these internal and external threats: if Mrs Reynolds is an example of ‘moral complacency’, her children’s behaviour embodies the ‘revolutionary spirit’ that appeared to threaten national security.I know not […] whether the increased insubordination of children is owing to the new school of philosophy and politics, but it seems to me to make part of the system […] There certainly prevails a spirit of independence, a revolutionary spirit, a separation from the parent state. It is the children’s world.(pp. 209–10)

5. A Fine Family-Piece: Disruptive Children in Persuasion

Austen generally avoids the politicized representations of children found in the work of her contemporaries; there is little in Sense and Sensibility to suggest that the disobedient Middleton children are emblematic of wider political turmoil. This tendency is best illustrated in her final completed novel, Persuasion. Children feature prominently in this novel, from the eldest Musgrove boy falling and fracturing his collarbone, to the moment when Captain Wentworth removes the younger Musgrove brother from Anne Elliot’s back. My focus is on the Christmas celebrations at Uppercross, which take place shortly before the action of the novel shifts to Bath. The scene Austen presents is a happier one than those in Sense and Sensibility, yet it too is plagued by ‘the problem of communication’ that critics have suggested defines Persuasion (Litz 1965, p. 153). Once more, this breakdown in communication is caused by the presence of boisterous children:

As she surveys this gathering, Anne is struck by the contrast with the ‘the last state she had seen [the room] in’, after the Musgroves’ sudden departure to visit the injured Louisa (p. 109). Filled with children and merriment, Uppercross ‘was already quite alive again’ (p. 109). Primarily, then, the presence of children is invigorating: they fill the room with vitality, energy and noise. Yet, like the tressels and trays ‘bending under the weight’ of Christmas food, this amiable scene is under strain: on the brink, perhaps, of an imminent collapse into chaos. To some degree, this collapse is forestalled by the spatial organisation of the room. Mrs Musgrove separates the Harville children from the young Musgroves, recalling the moment when she sits between Anne and Wentworth, providing ‘no insignificant barrier’ between them (as the narrator unflatteringly observes) (p. 59). Elsewhere, the room is divided on gender lines: the girls attend to their silk and paper, much as the women in Austen’s novels occupy themselves with needlework, while the boys hold ‘high revel’ amongst the food.Immediately surrounding Mrs. Musgrove were the little Harvilles, whom she was sedulously guarding from the tyranny of the two children from the Cottage, expressly arrived to amuse them. On one side was a table, occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel; the whole completed by a roaring Christmas fire, which seemed determined to be heard, in spite of all the noise of the others. Charles and Mary also came in, of course, during their visit, and Mr. Musgrove made a point of paying his respects to Lady Russell, and sat down close to her for ten minutes, talking with a very raised voice, but, from the clamour of the children on his knees, generally in vain. It was a fine family-piece.(pp. 109–10)

However, the spatial subdivisions of the room are undermined by the sheer noise that Austen describes. As Pinch comments, ‘noise is everywhere’ in Persuasion, and families are represented not just ‘in terms of the space they take up’ but by ‘the noise they make’ (Pinch 1996, p. 146). The overbearing noise of this scene gives a sense of its penetrative properties: its capacity to spill over spatial barriers and disrupt domestic order. Austen creates a cacophonous series of competing sounds, from the ‘chattering’ girls and ‘riotous boys’ to the collective ‘clamour’ of the children perched on Mr Musgrove’s knees. Additionally, it is not just human noise that is encountered: the description of the fire ‘roaring’ is, Austen suggests, more than figurative. It, too, competes for attention in this soundscape, providing another inarticulate voice ‘determined to be heard’.

Spatial and auditory chaos coincide at the end of the passage, in the form of the clamorous children on Mr Musgrove’s knees. The tendency of children to invade personal space is a recurring event in Persuasion. Sometimes it is benevolent, as when the Musgroves’ ‘little boys’ cling to Admiral Croft ‘like an old friend’ (p. 44); elsewhere, it is stifling and claustrophobic, most notably when Anne Elliot is assailed by her nephew, who ‘began to fasten himself upon her’ as she cares for his brother (p. 68). As Pinch notes, within Persuasion ‘bodily presence’ exerts a forceful pressure that impinges on ‘mental life’; but it also crowds out conversational life (Pinch 1996, p. 147). In this instance, the children’s physical weight reflects their auditory output: Mr Musgrove attempts to converse with Lady Russell, but his ‘raised voice’ only adds to the general cacophony. Once more, conversation is the casualty of childish exuberance.

Austen brings these festivities to a close with a short, ironic sentence that attempts to frame the merriment: ‘It was a fine family-piece’. This succinct summary echoes Coelebs in Search of Wife when, having presented the reader with the Stanley children, More’s first-person narrator concludes: ‘It was an animating scene’ (p. 118). In both instances, the narrator seeks to transform the preceding description into a stable visual image. In More’s case, there is a harmonious symmetry between the tableau of idealised domesticity and the narrator’s verdict. By contrast, Austen offers an incongruous juxtaposition between the overheated intensity of the Christmas celebrations and the cool economy of the narrator’s summary. Referring to this scene as a ‘family-piece’ implies precisely the kind of aesthetic order that it lacks. As a mode of painting, the ‘family piece’ is closely related to the popular eighteenth-century genre of the ‘conversation piece’. These group portraits were intended ‘to idealize the family’, depicting parents and children in domestic and informal settings while emphasising ‘social and convivial interaction’ (Flint 1995, p. 128; West 1995, p. 156). To label a scene a ‘family-piece’ thus suggests an artfully arranged image of domesticity that projects ‘a vision of harmony, happiness and health’ (West 1995, p. 164). Austen subverts such images by presenting instead a scene of domestic disorder, in which ‘convivial interaction’ is explicitly hindered by noisy children.

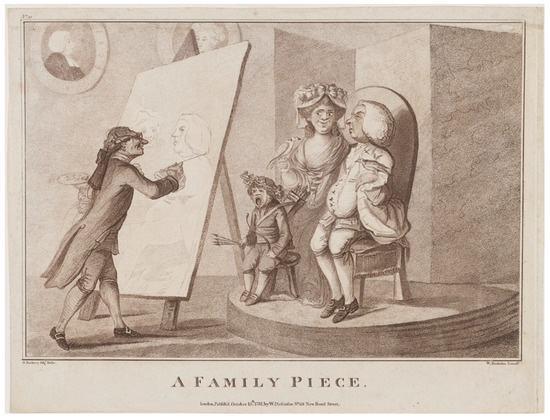

In this representation of children, Austen may have been influenced by the period’s visual culture, which similarly acknowledges the comic potential of disruptive children. Based on a painting by Henry William Bunbury, the engraving in Figure 1 is entitled ‘A Family Piece’. Depicting a painter in the act of committing two adults and their child to canvas, this image reveals the chaotic reality that lies behind idealised images of the family. Neither adult looks at ease, but it is their son—dressed as Cupid—who takes centre stage, signalling his annoyance with what is either a broad yawn of boredom or a noisy cry of displeasure. Arguably, a similar brand of satire informs Austen’s reference to a ‘family-piece’ in Persuasion. Indeed, the scene at Uppercross is a ‘fine’ family-piece: the adjective signals a certain pleasure or quiet amusement in the children’s disregard for social decorum. While this ‘domestic hurricane’ proves too much for Lady Russell to bear (she subsequently reminds herself never again to ‘call at Uppercross in the Christmas holidays’), it is treated more charitably by the narrator, whose sensibilities are more robust (p. 110). The critical judgment that the narrator casts over the Middleton children in Sense and Sensibility is absent here. Instead, the narrator’s tone is one of wry amusement at the disparity between the conventional image of idealized children, whether in painting or fiction, and the energetic and boisterous family life that she describes in Persuasion.

Figure 1.

William Dickinson, after Henry William Bunbury, A Family Piece (1781), stipple engraving, © National Portrait Gallery, London, UK.

Lady Russell’s distaste also marks this as a scene of generational conflict. Indeed, both Uppercross and the Musgrove family are associated with generational difference: ‘the father and mother were in the old English style, and the young people in the new’ (p. 38). This distinction is deepened by the contrast between the dynamic disorder of the ‘family-piece’, and the staid and serious portraits of past Musgroves, whom Austen imagines observing the children’s behaviour:

The appalled gaze of the family portraits presents an alternative way of viewing the Musgrove ‘family-piece’, but its morality is made to look censorious when compared with Austen’s playful irony. Indeed, Austen makes no ethical judgment when writing about the Christmas scene at Uppercross. The ‘overthrow of all order and neatness’ may echo More’s paranoid description of the ‘revolutionary spirit’ in families, but where More sees a threat to both the family and the fabric of the nation, Austen’s irony defuses any link between the domestic and the political.Oh! could the originals of the portraits against the wainscot, could the gentlemen in brown velvet and the ladies in blue satin have seen what was going on, have been conscious of such an overthrow of all order and neatness! The portraits themselves seemed to be staring in astonishment.(p. 37)

In one of her best-known pronouncements about her taste in ‘Novels and Heroines’, Austen declares that ‘pictures of perfection […] make me sick and wicked’ (Austen 1995, p. 335). Although her comment refers explicitly to heroines, it also makes sense of her depiction of children. While authors such as Edgeworth and More view children as the embodiment of Enlightenment hopes and Revolutionary fears, Austen abandons such explicit political commentary. Throughout her novels, children are a component of the family circle, but a fundamentally disruptive one. Their presence alone diminishes the possibility of conversation, making interpersonal interaction frictional rather than fluent. Rather than participants in enlightened conversation or part of an ‘animating scene’ of family life, Austen’s children provide a source of satirical humour, subverting the aesthetic conventions that would render them ‘pictures of perfection’. Moreover, despite these references to ‘pictures’ and ‘family-piece[s]’, the disruptive impact of Austen’s children is rendered not in visual terms, but in the language of sound. As I have been suggesting, Austen’s depictions of children are united by their overwhelming volume. This article began with Austen’s letters. There, the voices of her nieces and nephews possess a clarity that is absent among the ‘chattering’ and ‘clamour’ of Austen’s fictional children. Indeed, despite being the loudest characters in her novels, her children rarely say anything at all. Yet, it is precisely this inarticulacy that enables Austen to express her doubts about conversation’s status as a site of enlightened exchange.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | As Matthew Grenby notes, when reviewing children’s books in the first decade of the nineteenth century Sarah Trimmer was ‘prepared to consider books designed for readers up to the age of twenty-one’ (Grenby 2011, p. 11). |

| 2 | Anne K. Mellor summarises this understanding of Austen’s work when describing her fictions as ‘novels of female education […] in which an intelligent but ignorant girl learns to perceive the world more accurately, to understand more fully the ethical complexity of human nature and society, and to gain confidence in the wisdom of her own judgement’ (Mellor 1993, p. 53). |

| 3 | On politeness, see, for instance, Klein (1994). |

| 4 | As Cohen notes, it is difficult to retrieve the exact content and structure of such conversations, given that they exist ‘only in their written form’ and may be subject to the distortions of memory (Cohen 2009, p. 101). While they may be aspirational rather an accurate in their representations, children’s books of the period suggest that familial conversation encompassed a dizzying array of topics, including chemistry, engineering, manufacturing, mathematics, morals, ancient and modern history, geography and political economy. |

| 5 | The intellectual and moral transformation to which fictional dialogues aspired is signaled in the subtitles of works such as Priscilla Wakefield’s Mental Improvement: or the Beauties and Wonders of Nature and Art, Conveyed in a Series of Instructive Conversations (1794) and Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories from Real Life; with Conversations Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness (1788). |

| 6 | As Rousseau notes, this ‘love of power’ is not inherent to children but is taught to them by the poor example set by their parents. Austen’s representation of the indulgent parenting of Lady Middleton would seem to confirm this link. |

| 7 | Although Hannah More’s opposition to the French Revolution has often resulted in her being labelled a conservative, it is important to note that she is a complex and, in many respects, progressive thinker. As William Stafford notes, ostensibly ‘proper’, ‘antijacobin’ women writers like More ‘continued to promote women’s issues’ in a way that aligned them with their putatively radical counterparts (Stafford 2002, p. 34). |

| 8 | Even so, despite recognising the deficiency of his daughters’ upbringing Sir Thomas absolves himself of blame by reflecting that ‘something must have been wanting within’ his daughters (p. 364). |

References

- Austen, Jane. 1995. Jane Austen’s Letters, 3rd ed. Edited by Deirdre Le Faye. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, Jane. 2003. Mansfield Park. Edited by James Kinsley. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, Jane. 2004. Persuasion. Edited by James Kinsley. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, Jane. 2006. Henry and Eliza. In Juvenilia. Edited by Peter Sabor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, Jane. 2017. Sense and Sensibility. Edited by John Mullan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Marshall. 2014. Emma’s Depression. Studies in Romanticism 53: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleere, Eileen. 2007. Homeland Security: Political and Domestic Economy in Hannah More’s Coelebs in Search of a Wife. ELH 74: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocks, Neil. 2014. The Peripheral Child in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Its Criticism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Michèle. 2009. ‘Familiar Conversation’: The Role of the ‘Familiar Format’ in Education in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century England. In Educating the Child in Enlightenment Britain: Beliefs, Cultures, Practices. Edited by Mary Hilton and Jill Shefrin. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Cowper, William. 1979–1986. The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper. Edited by James King and Charles Ryskamp. 5 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demers, Patricia. 2007. Introduction to Hannah More. In Coelebs in Search of a Wife. Edited by Patricia Demers. Peterborough: Broadview. [Google Scholar]

- Edgeworth, Maria. 1798. Practical Education. 2 vols. London: J. Johnson. [Google Scholar]

- Edgeworth, Maria. 1994. Belinda. Edited by Kathryn J. Kirkpatrick. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Frances. 2017. Rousseau, Emile and Britain. In Jean-Jacques Rousseau and British Romanticism: Gender and Selfhood, Politics and Nation. Edited by Russell Goulbourne and David Higgins. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 187–207. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, Christopher. 1995. ‘The Family Piece’: Oliver Goldsmith and the Politics of the Everyday in Eighteenth-Century Domestic Portraiture. Eighteenth-Century Studies 29: 127–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, Aileen. 2000. Reading Children’s Books in Late Eighteenth-Century Dissenting Families. The Historical Journal 43: 453–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenby, M. O. 2011. The Child Reader, 1700–1840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, Harriet. 2013. Unbounded Attachment: Sentiment and Politics in the Age of the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Translated by Thomas Burger, and Frederick Lawrence. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heydt-Stevenson, Jill. 2005. Austen’s Unbecoming Conjunctions: Subversive Laughter, Embodied History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Howell Michaelson, Patricia. 2002. Speaking Volumes: Women, Reading, and Speech in the Age of Austen. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Claudia L. 1988. Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Lawrence E. 1994. Shaftesbury and the Culture of Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knox-Shaw, Peter. 2004. Jane Austen and the Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Litz, A. Walton. 1965. Jane Austen: A Study of her Artistic Development. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, John. 1996. Some Thoughts Concerning Education and of the Conduct of the Understanding. Edited by Ruth W. Grant and Nathan Tarcov. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett. [Google Scholar]

- Manly, Susan. 2007. Language, Custom and Nation in the 1790s: Locke, Tooke, Wordsworth, Edgeworth. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster, Juliet. 2010. Jane Austen’s Children. Persuasions: The Jane Austen Journal Online 31: 1. Available online: https://jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol31no1/mcmaster.html (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Mee, Jon. 2011. Conversable Worlds: Literature, Contention and Community, 1762 to 1830. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, Anne K. 1993. Romanticism and Gender. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Milton, John. 2004. Paradise Lost. Edited by Stephen Orgel and Jonathan Goldberg. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- More, Hannah. 1799. Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education. With a View of the Principles and Conduct Prevalent among Women of Rank and Fortune. 2 vols. London: T. Cadell, Jnr. and W. Davies, pp. 134–35. [Google Scholar]

- More, Hannah. 2007. Coelebs in Search of a Wife. Edited by Patricia Demers. Peterborough: Broadview. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Anja. 2006. Introduction. In Fashioning Childhood in the Eighteenth Century: Age and Identity. Edited by Anja Müller. London: Routledge, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Mitzi. 1999. ‘Anecdotes from the Nursery’ in Maria Edgeworth’s Practical Education (1798): Learning from Children ‘Abroad and at Home’. The Princeton University Library Chronicle 60: 220–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, Kate. 2015. ‘Taste in Noises’: Registering, Evaluating, and Creating Sound and Story in Jane Austen’s Persuasion. Studies in the Novel 47: 451–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunokawa, Jeff. 2005. Speechless in Austen. Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 16: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinch, Adela. 1996. Strange Fits of Passion: Epistemologies of Emotion, Hume to Austen. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, John Greville Agard. 1985. Virtue, Commerce, and History: Essays on Political Thought and History, Chiefly in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1950. Emile. Translated by Barbara Foxley. London: J. M. Dent. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, David. 2010. Jane Austen and Children. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Adam. 1976. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Edited by D. D. Raphael and A. L. Macfie. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, William. 2002. English Feminists and Their Opponents in the 1790s: Unsex’d and Proper Females. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Kevin. 2018. ‘Eccentric Murmurs’: Noise, Voice, and Unreliable Narration in Jane Eyre. Narrative 26: 202–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, Kathryn. 2009. Jane Austen’s Life and Letters. In A Companion to Jane Austen. Edited by Claudia L. Johnson and Clara Tuite. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, Bharat. 2003. Jane Austen and the Morality of Conversation. London: Anthem. [Google Scholar]

- West, Shearer. 1995. The Public Nature of Private Life: The Conversation Piece and the Fragmented Family. British Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 18: 153–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Nicole M. 2012. Opening the Phosphoric ‘Envelope’: Scientific Appraisal, Domestic Spectacle, and (Un)’Reasonable Creatures’ in Edgeworth’s Belinda. Eighteenth-Century Fiction 24: 509–36. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).