An Approach to Understand Rural Advisory Services in a Decentralised Setting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

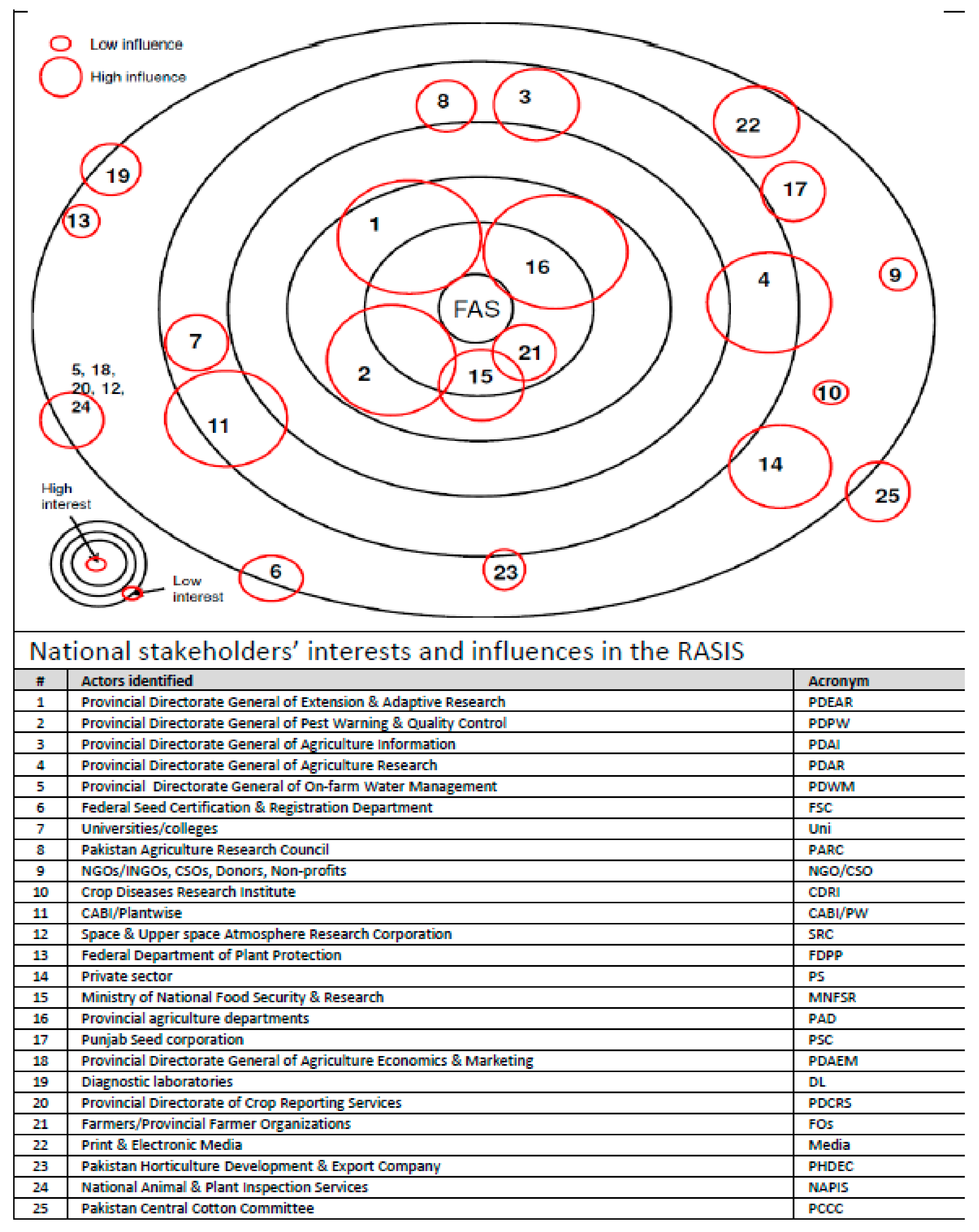

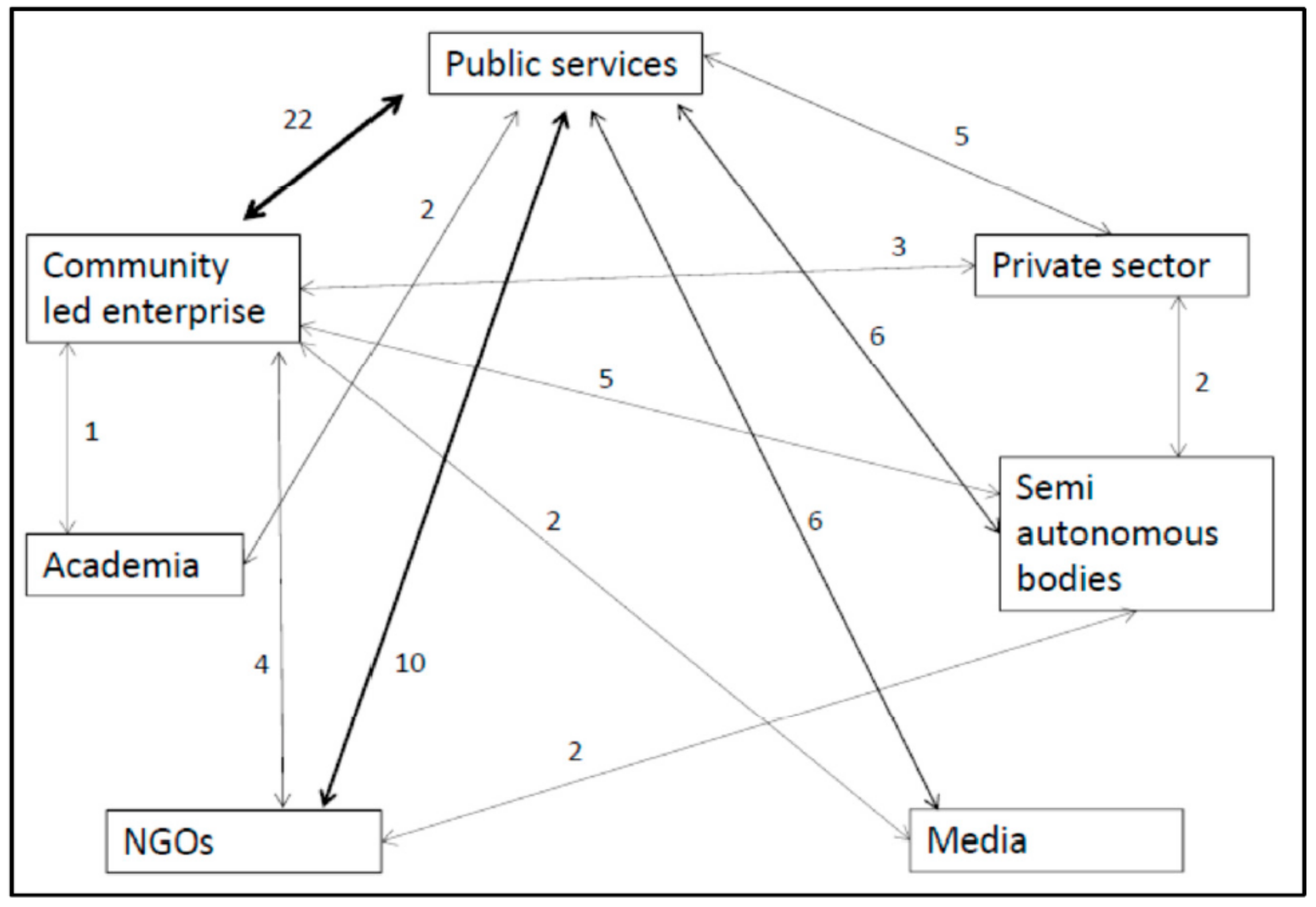

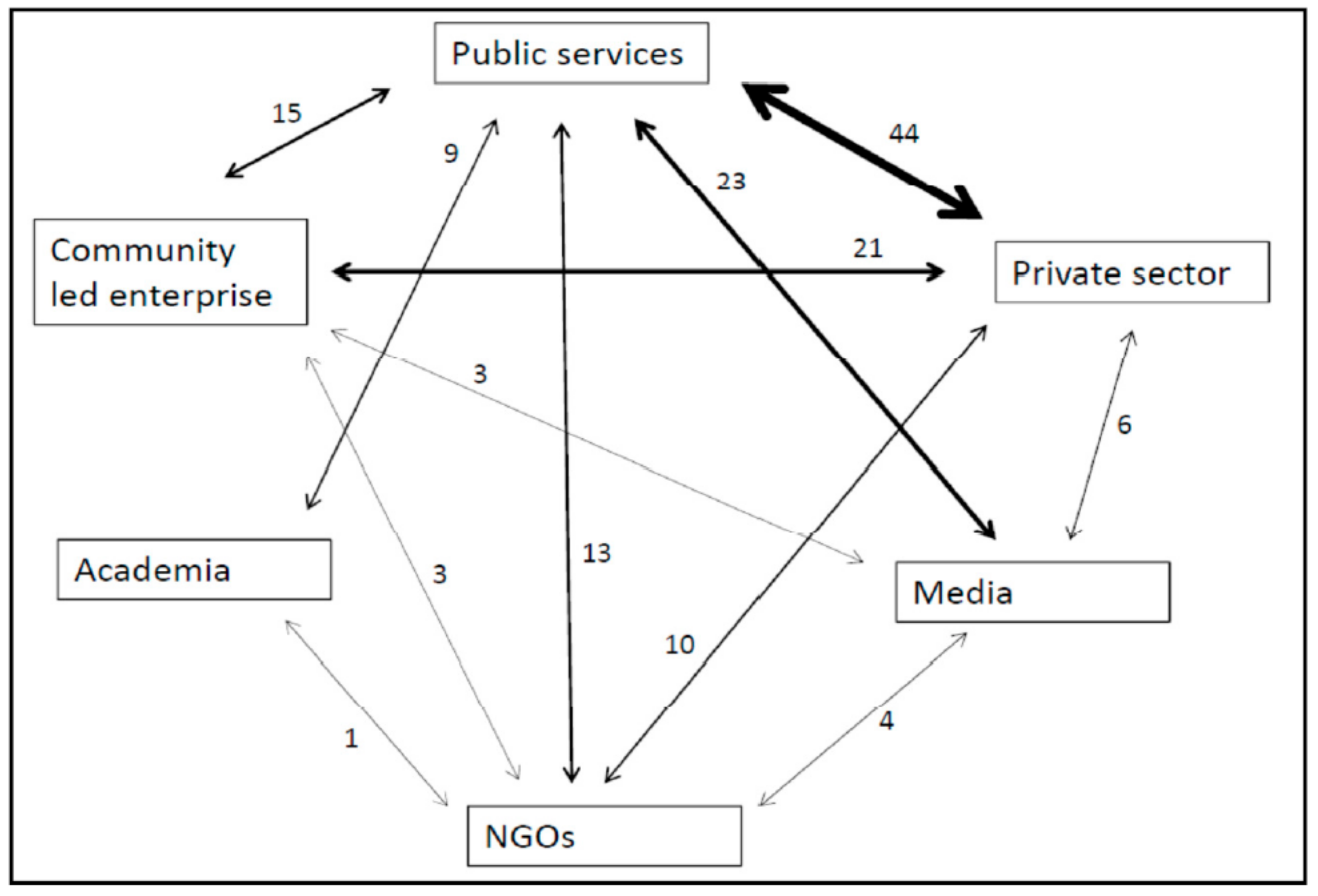

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Public Sector

3.2. Private Sector

3.3. Non-Government Organisations

3.4. Community Level Enterprise

3.5. Media

3.6. Academic

4. Discussion

4.1. Highlighting Decentralisation Issues

4.2. Highlighting an Initiative’s Position and Durability in a System

4.3. Recommendations for Advisory Services

4.4. Approach Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, Mazher, Toheed Elahi Lodhi, Khalid Mahmood Aujla, and Shawana Saadullah. 2009. An agricultural extension programs in Punjab. Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences 7: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Shoukat, Munir Ahmad, and Muhammad Luqman. 2011. Role of private extension system in agricultural development through advisory services in the Punjab, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Sciences 63: 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Amjad, Rashid, Ghulam M. Arif, and Usman Mustafa. 2008. Does the Labor Market Structure Explain Differences in Poverty in Rural Punjab? Islamabad: Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Anaeto, Frank C., C. C. Asiabaka, F. N. Nnadi, J. O. Ajaero, O. O. Aja, F. O. Ugwoke, M. U. Ukpongson, and A. E. Onweagba. 2012. The role of extension officers and extension services in the development of agriculture in Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Research 1: 180–85. [Google Scholar]

- Atari, D. O. Atari, Emmanuel K. Yiridoe, Shawn Smale, and Peter N. Duinker. 2009. What motivates farmers to participate in the Nova Scotia environmental farm plan program? Evidence and environmental policy implications. Journal of Environmental Management 90: 1269–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autio, Erkko, Martin Kenney, Philippe Mustar, Don Siegel, and Mike Wright. 2014. Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Research Policy 43: 1097–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, Munir, and Ali Khan. 1982. Natural enemies of paddy pests in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Agriculture Research 3: 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, Lynda, and Derek H. T. Walker. 2005. Visualising and mapping stakeholder influence. Management Decision 43: 649–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugha, Ruairí, and Zsuzsa Varvasovszky. 2000. Stakeholder Analysis: A Review. Health Policy Plan 15: 239–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Martin, Turi Fileccia, Aidan Gulliver, Marat Qamar, and Ali Tayyab. 2012. Pakistan: Priority Areas for Investment in the Agricultural Sector. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Nuno, Luisa Carvalho, and Sandra Nunes. 2015. A methodology to measure innovation in European Union through the national innovation system. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development 6: 159–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, Khalid. 2014. Gender Inequality in the Public Sector in Pakistan: Representation and Distribution of Resources. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, John, and Kazuyo Machiyama. 2017. The Challenges Posed by Demographic Change in sub-Saharan Africa: A Concise Overview. Population and Development Review 43: 264–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Allura, Giorgia, Marco Galvagno, and Arabella Mocciaro Li Destri. 2012. Regional Innovation Systems: A Literature Review. Business Systems Review 1: 139–56. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen, Solveig, and Frank B. Matsiko. 2016. Using a plant health system framework to assess plant clinic performance in Uganda. Food Security 8: 345–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Andrew P., and Munir Ahmad. 2002. Effectiveness of public and private sector agricultural extension: Implications for privatisation in Pakistan. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 8: 117–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Andrew P., Munir Ahmad, and Tanvir Ali. 2001. Dilemmas of Agricultural Extension in Pakistan: Food for Thought. Washington, DC: Agricultural Research and Extension Network. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Agricultural Extension Punjab. 2016. Available online: www.agripunjab.gov.pk (accessed on 3 November 2016).

- Esparcia, Javier. 2014. Innovation and networks in rural areas. An analysis from European innovative projects. Journal of Rural Studies 34: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, Jessica, Quinn Marshall, Darja Dobermann, Joyce Wong, and Rafael I. Merchan. 2015. Integration of nutrition into extension and advisory services: A synthesis of experiences, lessons, and recommendations. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 36: 120–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. 2015. Women in Agriculture in Pakistan. Available online: www.fao.org/3/a-i4330e.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2016).

- FAO, IFAD, and WFP. 2015. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015: Meeting the 2015 International Hunger Targets: Taking Stock of Uneven Progress. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Finegold, Cambria, Mary Lucy Oronje, Margo C. Leach, Teresia Karanja, Florence Chege, and Shaun Hobbs. 2015. Plantwise Knowledge Bank: Building sustainable data and information processes to support plant clinics in Kenya. Agricultural Information Worldwide 6: 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Christopher. 1987. Technology Policy and Economic Performance: Lessons from Japan. London: Pinter. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Mushtaq Ahmad, and Khurram Mushtaq. 1998. A Case Study of Punjab Agriculture Department. Lahore: Pakistan National Programme International Irrigation Management Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Global Forum of Rural Advisory Services. 2016. Five Key Areas for Mobilising the Potential of Rural Advisory Services. Lausanne: Global Forum of Rural Advisory Services. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Yousuf Zakaria Muhammad, Tanvir Ali, and Munir Ahmad. 2007. Determination of participation in agricultural activities and access to sources of information by gender: A case study of district Muzaffargarh. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences 44: 664–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, Maliha Hamid. 2009. State of Microfinance in Pakistan. Available online: http://inm.org.bd/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Pakistan.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2016).

- Ingram, Julie. 2008. Agronomist–farmer knowledge encounters: An analysis of knowledge exchange in the context of best management practices in England. Agriculture and Human Values 25: 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fund for Agricultural Development. 2013. Smallholders, Food Security and the Environment. Rome: United Nations Environment Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Intikhab, Amir. 2014. Farm Services Centres for all KP Districts. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1082993 (accessed on 3 November 2016).

- Jones, Gwyn E., and Chris Garforth. 1997. The History, Development, and Future of Agricultural Extension. Rome: United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- Kania, Jozef, Krystyna Vinohradnik, and Agnieszka Tworzyk. 2014. Advisory services in agricultural system of knowledge and information in Poland. Paper presented at 11th European IFSA Symposium, Berlin, Germany, April 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Sajjad Ali. 2015. Devolution Plan 2000: Dictatorship, democracy, and the politics of institutional change in Pakistan. Development in Practice 25: 574–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Muhammad Zafarullah, Tario Shah, Asif Nawaz, Rehmat Ullah, Ikram Haq, Khattam Haq, and Abdur Rahman. 2017. Farmers’ empowerment under FSC approach regarding selected agricultural inputs in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. International Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Research 3: 250–59. [Google Scholar]

- Khooharo, Ali. 2008. A Study of Public and Private Sector Pesticide Extension and Marketing Services for Cotton Crop. Ph. D. thesis, Agricultural University of Tandojam, Sindh, Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- Khooharo, Ali, Roger Memon, and Mohammed Lakho. 2008. An assessment of farmers’ level of knowledge about proper usage of pesticides in Sindh Province of Pakistan. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture 24: 531–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kingiri, Ann N. 2013. A Review of Innovation Systems Framework as a Tool for Gendering Agricultural Innovations: Exploring Gender Learning and System Empowerment. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 19: 521–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, Laurens, Karin De Grip, and Cees Leeuwis. 2006. Hands off but Strings Attached: The Contradictions of Policy-induced Demand-driven Agricultural Extension. Agriculture and Human Values 23: 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, Laurens, Noelle Aarts, and Cees Leeuwis. 2010. Adaptive management in agricultural innovation systems: The interactions between innovation networks and their environment. Agricultural Systems 103: 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarthe, Pierre. 2009. Extension services and multifunctional agriculture. Lessons learnt from the French and Dutch contexts and approaches. Journal of Environmental Management 2: 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne-Godwin, Julien, Frances Williams, Bandara Willoru Mudiyansele Palitha Thilakasiri, and Ziporah Appiah-Kubi. 2017. Quality of extension advice: A gendered case study from Ghana and Sri Lanka. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 23: 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne-Godwin, Julien, Frances Williams, Naeem Aslam, Sarah Cardey, Peter Dorward, and M. Almas. 2018. Gender differences in use and preferences of agricultural information sources in Pakistan. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 24: 419–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwis, Cees, and Anne van den Ban. 2004. Communication for Rural Innovation: Rethinking Agricultural Extension. Oxford: Blackwell Science. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg, Marc, and Benjamin Crosby. 1981. Managing Development: The Political Dimension. Hartford Connecticut: Kumarian Press. [Google Scholar]

- Looney, Robert E. 1999. Private sector investment in Pakistani agriculture: The role of infrastructural investment. Journal of Development Science 15: 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall, Bengt-Åke. 1992. Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. Introduction in National Systems of Innovation. London: Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Luqman, Muhammad, Ahmed Kafeel, Mohammed Ashraf, and Zareef Khan. 2007. Effectiveness of decentralised agricultural extension system (a case study of Pakistan). African Crop Science Conference Proceedings 8: 1465–72. [Google Scholar]

- Manderson, Andrew K., Alec D. Mackay, and Alan P. Palmer. 2007. Environmental whole farm management plans: Their character, diversity, and use as agri-environmental indicators in New Zealand. Journal of Environmental Management 82: 319–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayers, James, and Sonja Vermeulen. 2005. Stakeholder Influence Mapping. London: International Institute of Environment and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Mengal, Ahmed, Zaheeruddin Mirani, and Habibullah Magsi. 2014. Historical overview of agricultural extension services in Pakistan. The Macrotheme Review 3: 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mur, Remco, Frances Williams, Solveig Danielsen, Gabrielle Audet-Bélanger, and Joseph Mulema. 2015. Listening to the Silent Patient: Uganda’s Journey towards Institutionalizing Inclusive Plant Health Services. Wallingford: CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Nagrah, Aatika, Anita M. Chaudhry, and Mark Giordano. 2016. Collective Action in Decentralized Irrigation Systems: Evidence from Pakistan. World Development 8: 282–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Richard R., and Katherine Nelson. 2002. Technology, institutions, and innovation systems. Research Policy 31: 265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, Robert. 2003. From client to project stakeholders: A stakeholder mapping approach. Construction Management and Economics 21: 841–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, Erich-Christian. 2006. Crop losses to pests. The Journal of Agricultural Science 144: 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 2019. Jhang and Bahawalpur District Profiles. Available online: http://www.pbscensus.gov.pk/sites/default/files/bwpsr/punjab/BAHAWALPUR_SUMMARY.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Peterman, Amber, Agnes Quisumbing, Julia Behrman, and Ekonya Nkonya. 2011. Understanding the complexities surrounding gender differences in agricultural productivity in Nigeria and Uganda. Journal of Development Studies 47: 1482–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantwise. 2015. Available online: www.plantwise.org (accessed on 3 November 2016).

- Qureshi, Sarfraz Khan, and Ghulam Mohammad Arif. 2001. Profile of Poverty in Pakistan. Islamabad: Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, Hafiz Mahmood Ur, Riaz Mahmood, and Muhammad Razaq. 2014. Occurrence, monitoring techniques and management of Dasineura amaramanjarae Grover (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) in Punjab, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 46: 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, Muhammad. 2010. The role of the private sector in agricultural extension in Pakistan. Rural Development News 1: 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, William M. 2011. Public Sector Agricultural Extension System Reform and the Challenges Ahead. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 17: 165–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, Vittorio, Tito Caffi, and Francesca Salinari. 2012. Helping farmers face the increasing complexity of decision-making for crop protection. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 51: 457–479. [Google Scholar]

- Schrempf, Benjamin, David Kaplan, and Doris Schroeder. 2013. National, Regional, and Sectoral Systems of Innovation—An Overview. Brussel: European Comission. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Tariq, Jianping Tao, Muhammand Zafarullah Khan, and Farooq Shah. 2016. Analysing the Performance of Member and Non-member Farming Community of Model Farm Services Centre in District Dera Ismail Khan. Pakistan Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences 6: 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz, Baar, and Salman Ata. 2014. Enabling Agricultural Policies for Benefiting Smallholders in Dairy, Citrus and Mango Industries of Pakistan. Available online: http://www.vises.org.au/documents/2014_Sept_Background_Paper_1_Agriculture_Extension_Services_Pakistan.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2016).

- Shahbaz, Babar, Tanvir Ali, and Abid Suleri. 2011. Dilemmas and challenges in forest conservation and development interventions: Case of Northwest Pakistan. Forest Policy and Economics 13: 473–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, David, Javier Ekboir, and Kristin Davis. 2009. The art and science of innovation systems inquiry: Application to Sub-Saharan agriculture. Technology in Society 31: 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals. 2017. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2016).

- Sutherland, Lee-Ann, Jane Mills, Julie Ingram, Rob J. F. Burton, Janet Dwyer, and Kirsty Blackstock. 2013. Considering the source: Commercialisation and trust in agri-environmental information and advisory services in England. Journal of Environmental Management 118: 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ul-Haq, Muhammad Anwar, Yan Jingdong, Nazar Hussain Phulpoto, and Muhammad Usman. 2014. Analysing National Innovation System of Pakistan. Developing Country Studies 4: 133–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid, Abdul, Muhammand Ahmad, Noraini Bt. Abu Talib, Iqtidar Ali Shah, Muhammad Tahir, Farzand Ali Jan, and Muhammad Qaiser Saleem. 2017. Barriers to empowerment: Assessment of community-led local development organizations in Pakistan. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 74: 1361–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War, A. Rashid, Gaurav Kumar Taggar, Mohd Yousuf War, and Barkat Hussain. 2016. Impact of climate change on insect pests, plant chemical ecology, tritrophic interactions and food production. International Journal of Clinical and Biological Science 1: 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Yuan. 2009. Improving the livelihood of smallholder farmers. Agriculture Extension. Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture 2010: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| Background Information | National Workshop | Local Workshop | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Total | Districts | ||

| Jhang | Bahawalpur | |||

| Number of respondents | 25 | 19 | 10 | 9 |

| Number of men | 25 | 17 | 8 | 9 |

| Number of women | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Number of groups | 1 | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Number of all male groups | 1 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Number of all female groups | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Number of high-level decision makers | 19 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Number of middle level workers | 6 | 11 | 4 | 7 |

| Number of low-level workers | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Number of post graduate education holders | 25 | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Number of graduate education holders | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Number of diploma holders | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Number of different departments represented | 19 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Median years of experience in extension | N/A | 13.5 | 16 | 11 |

| Average years of experience in extension | N/A | 14 | 16 | 12 |

| Categorisation of Sector | National Workshop | Local Workshop | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Stakeholder | Number | Name of Stakeholder | Number | |

| Public services | FDPP; FSC; MNFSR; PARC; CDRI; PDEAR; PDAR; PDPW; PDAI; PDWM; PDAEM; PDCRS; NAPIS | 13 | PDEAR; PDAR; PDPW; PDAI; Agricultural Research Farms; Government Nurseries | 6 |

| Semi-autonomous bodies | PSC; PCCC; SRC | 3 | 0 | |

| Private sector | Private sector; PHDEC | 2 | Pesticide companies/dealers; Fertiliser companies/dealers; Seed Companies | 5 |

| Non-governmental | NGO/CSO; CABI/Plantwise | 2 | NGO/CSO; WWF; CABI; NRSP | 4 |

| Community led | Farmer organisations | 1 | Community Leader; Farmer to farmer; farmer organisations | 3 |

| Academic | Universities | 1 | Universities | 1 |

| Media | Print and electronic media | 1 | Radio; television; Print media; Help call centres | 4 |

| Other | Diagnostic Laboratories; Provincial agriculture departments | 2 | Plant Clinics; Plant Doctors | 2 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lamontagne-Godwin, J.; Dorward, P.; Ali, I.; Aslam, N.; Cardey, S. An Approach to Understand Rural Advisory Services in a Decentralised Setting. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030103

Lamontagne-Godwin J, Dorward P, Ali I, Aslam N, Cardey S. An Approach to Understand Rural Advisory Services in a Decentralised Setting. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(3):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030103

Chicago/Turabian StyleLamontagne-Godwin, Julien, Peter Dorward, Irshad Ali, Naeem Aslam, and Sarah Cardey. 2019. "An Approach to Understand Rural Advisory Services in a Decentralised Setting" Social Sciences 8, no. 3: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030103

APA StyleLamontagne-Godwin, J., Dorward, P., Ali, I., Aslam, N., & Cardey, S. (2019). An Approach to Understand Rural Advisory Services in a Decentralised Setting. Social Sciences, 8(3), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030103