1. Introduction

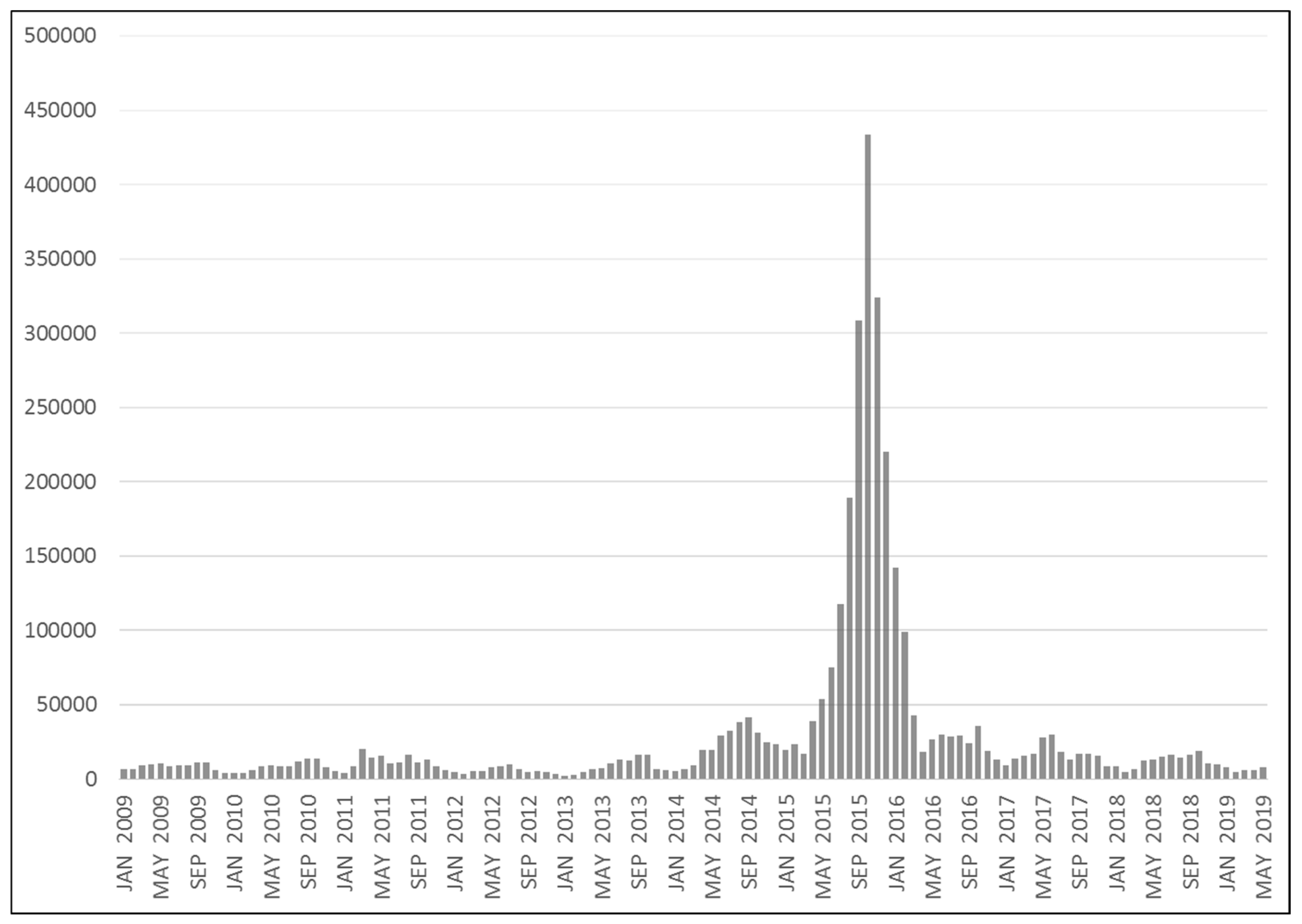

The unexpected, large-scale inflow of non-European citizens on the territory of the European Union (EU) during several months in the years 2015–2016 has been called the “migration crisis” and a “humanitarian crisis” (

Martin 2016;

Baldwin-Edwards et al. 2018;

Dunes et al. 2018). The data and analyses of International Organization for Migration (IOM), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) were alarming (see

Figure 1). It was pointed out that “post-war Europe did not know this phenomenon” (

Cianciara 2015, p. 430). The migration crisis has become one of the most important subject matters capturing public attention for many months. In this context, two faces of the movement of immigrants and refugees have been presented. The first portrays the mass inflow of people from outside Europe, mainly men, and has been discussed a lot in the media, such that it finally also caught Polish public attention, despite the fact that Poland has not experienced immigration of this kind on such a large scale. The second is related to the actual cases of migration to Poland during the migration crisis, which were in line with earlier patterns of refugee arrivals to Poland and had different characteristics than the discussed “crisis”. It seems that these arrivals do not arouse controversy in Poland and are beyond public debate. What focused Poles’ attention was the refugee inflow to other EU countries, and this is what became the “carrier” of the idea of “migration crisis” to Poland. This is also why the words “the so-called” sometimes precede “migration crisis” in this text.

Information about tragic accidents and human drama of immigrants and refugees arriving in Europe through the Mediterranean Sea has aroused social emotions and has not allowed people to remain indifferent to these events. The IOM, which began to collect and publish data on the number of deaths and drownings during these crossings, demonstrates large numbers which significantly exceed 1000 people per year, namely: 3317, 3416 and 5096 casualties in years 2014–2016, respectively (

Fargues 2017, p. 13). Such information, being disseminated and visualized against the background of arriving people, mostly young men, resulted in polarization of social attitudes towards the current policy of admitting immigrants and refugees. Some expected that a strict immigration policy would be adopted in order to prevent such situations from recurring. Others demanded that the policy be softened and greater openness should be shown to those who take trouble and risk their lives to reach safe countries.

In Poland, the migration crisis became a media event since the beginning. At its peak, neither the increase in the number of refugees nor the phenomenon of large and uncontrolled inflow of foreigners from outside Europe were noticed. According to the data from the Office for Foreigners, the number of persons who applied for refugee status even decreased slightly (

Urząd do Spraw Cudzoziemców 2015). Still, a very critical attitude of Poles towards refugees can be observed, although they have little experience of hosting them in Poland (

Łaciak and Segeš Frelak 2018). By disseminating information, films and photos showing different faces of the migration crisis, electronic and traditional mass media have contributed to this effect. The nature of the media message is that it says whatever attracts attention, according to the old journalistic principle:

bad news is good news. As a result, the message about the migration crisis was dominated almost exclusively by negative content. Besides, the very concept of “the migration crisis” is not neutral in itself. Polish society has already experienced many political and economic crises and is not willing to face another. All the more so that in the neighboring Germany, a richer and better organized country, with a long tradition of hosting migrants (

Stokes 2019), this major increase in the number of refugees and immigrants caused a lot of confusion, growing concerns about security in public spaces (

Stecker and Debus 2019) and “the crisis has also heightened anti-foreigner racism, prejudice and marginality for existing immigrant communities” (

Sadeghi 2019, p. 1625). The peak of media and society’s interest in the so called migration crisis in Poland coincided with the campaign for the parliamentary elections in Poland in 2015, and debates on the character of the Polish State’s policy, including the policy towards migration. Concepts such as

refugees,

immigrants or

migrants, frequently used in public debates, became popular expressions, used intuitively and ambiguously. They played an important role as a catalyst of division. Two groups emerged: the opponents and the supporters of the “open door” policy. This dichotomous, and thus simplified way of practicing migration policy fit well into the election campaign, because it made it easy to distinguish between these two groups of politicians. However, it is known that migration policies are much more complex and ambiguous in practice. The dichotomous approach to this matter reflects different visions of Poland’s future: multi-ethnic and multicultural or national and with little cultural and ethnic diversity. We point out that after the peak of the migration crisis the migration issues ceased to be central to mass media and their role in political campaigns became less significant (see the end of

Section 4).

The manifestations of society’s interest in the so-called migration crisis took various forms: from street marches (in 2015 they were organized in the largest Polish cities) through public debates (including broadcasts on nationwide and regional radio and television stations) to publications of statements released by various organizations and opinion-forming circles (including, for example, the Polish Sociological Association or the Committee on Migration Research of Polish Academy of Science). At the same time, while street marches attracted mainly the opponents of immigrants’ and refugees’ admission to Poland, the debates were attended by people who worked with refugees and experts. The issuing of statements was a typical form of expression for the supporters of the “open door” policy. However, the parliamentary elections in October 2015 were successful for the parties declaring the “defense” of Poland against the mass arrival of immigrants and refugees.

Poles’ attitudes towards the immigration to Poland in the context of the European migration crisis have already been discussed in various aspects by many Polish scholars and experts in the field of migration and refugee studies. The themes explored concerned mainly such problems as: the need for a more balanced and reliable vision of immigration and refugee issues in public discussion (

Goździak and Márton 2018), the Catholic Church, the State and civil society’s reactions to the idea of possibly receiving refugees in Poland (

Narkowicz 2018), or the Islamophobia in Polish society and ambiguities of opinions towards Muslims and Islam (

Pędziwiatr 2018). A lot of space was devoted to the general discussion of the arguments presented by the supporters and opponents of receiving migrants in Poland, as well as the factors that determined shaping Polish society’s perception towards immigrants (

Hodór and Kosińska 2016). In this article, Poles’ attitudes are also presented, however, the text hopes to bring a new perspective to the ongoing discussion on the current migration issues by addressing specific problems. First, there is the question about the characteristics of the latest wave of immigrants arriving in European Union countries and whether these features distinguish it from the waves preceding the migration crisis; if there are such differences, what are they? The second purpose of the analysis is to present the reaction of Polish society to the EU policy on the relocation of refugees, and an attempt to explain this reaction. The third is the issue of the possible impact of the migration crisis on the course and outcome of parliamentary elections in Poland in October 2015. The text is divided according to the following issues. First, the sociological concept of the ideal type is used to frame the data and the analysis of the features of refugee migration in times of the migration crisis (there is a synonymous term—

refugeenes (

Malkki 1996). Second, the scale and specificity of taking refuge in Poland is presented. Third, social reactions to relocation plans for refugees in Poland are explored, including popular opinions about migrants’ health condition. Fourth, the experiences of hosting and integrating refugees into the society of a Polish city, by an active refugee center, are discussed. In the last section, public opinion on the relocation of refugees is introduced and, finally, conclusions are drawn.

2. Asylum Seekers Ideal Type versus Actual Characteristics

The so called European migration crisis has highlighted the difficulties associated with the classification of incoming people. For years, there have been problems with distinguishing refugees from other categories of migrants (

Hein 1993). Under the Geneva Convention of 1951, a refugee is a person who:

owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

The key phrase in this definition is “fear of being persecuted” and various sources of persecution are mentioned. The decision about granting the refugee status is motivated by the assessment of the concerns of the person seeking protection and whether they are justified. The refugee status is, therefore, not automatically obtained after submitting the application. In Poland, the application is submitted through the Border Guard. In practice, the processing of each application often takes many months.

Karin Scherschel (

2011), referring to the situation in Germany, notes that administrative procedures strongly affect the experiences of refugees in the host society. Throughout this time the situation of such people remains unclear and the problem of migrants with an undefined social status is growing.

The ideal type, a tool used by sociologists to describe and classify the studied phenomena, allows for viewing the refugee situation in such a way as to take into account different criteria. Although the legal aspect of the refugee experience, being a formal criterion, has significant practical meaning (people recognized as refugees gain a number of rights in the host society), it is not sufficient enough to capture the essence of this experience in the sociological sense.

The legal criterion allows classification of refugees as legal migrants i.e., registered migration. This means that the newcomers are required to register, and the state authorities are required to register them. Registration is the step towards state control over the inflow, and, at the same time, provides refugee candidates with the sense of security, including social security. The migration crisis did not introduce any significant changes in this respect, but it proved that it is easy to disturb the balance of the flow control system and make it ineffective. A good example of an effect of this kind is the famous statement of the German Chancellor Angela Merkel at a press conference in Berlin on 31 August 2015 (

Sakson 2016). The Chancellor emboldened the individuals arriving from outside Europe to bypass the EU border crossing procedures. Several days earlier Germany suspended the 1990 Dublin protocol which forces refugees to seek asylum in the first European country in which they set foot (

Hall and Lichfield 2015). This led to conflicts within the member states of the European Union. The Polish government, elected in the 2015 general election, consistently opposed both the weakening of control over migration movements and the obligatory relocation of refugees. Soon, by the end of 2015, also the public acceptance of immigrants in Germany decreased significantly (

Czymara and Schmidt-Catran 2017).

The criterion of voluntariness is an important distinguishing feature in the classification of migration inflow. Refugee migration (exile) is forced migration (

Kawczyńska-Butrym 2009, pp. 16–17). In addition to seeking asylum there are also other types of involuntary migration, such as displacement, resettlement, or deportation. In case of seeking refuge, the involuntariness results from the necessity of escape from the country of origin and the need to stay abroad as long as it is required, regardless of individual preferences and plans. A refugee, unlike an economic immigrant (

Cieślińska 2014), cannot visit his/her country of origin during the period of his/her refuge. Also, he/she cannot plan the date of his/her return, and, by the same token, the length of his/her stay in the country in which he/she found refuge. An additional feature of seeking asylum as forced migration is the individualized nature of this migration: “refugee migration (…) is not a mass migration, or migration organized by the units which do not participate in it” (

Okólski and Fihel 2012, p. 214). To some extent, for this reason, refugees are easier to control, as each case requires separate consideration. The important feature of the European migration crisis is the mass inflow of individuals and organized character of the trips.

In the search for features of the ideal type of refugee migration, it is worth paying attention to the criterion of the duration of stay. Empirical studies show that refugees’ stay in the host country is temporary (

Malkki 1996). Refugees stay in the country that gives them a safe refuge; the stay should end with their return to the country of origin or return “to the national order of things” (

Malkki 1995b;

Pluta 2008). This includes methods of refugee settlement applied by UNHCR like repatriation, integration with the host society or resettlement to a third country (

Pluta 2008, p. 36). However, it is becoming clear that this is not a generally applicable rule. An example may be the refugee experience of Poles who were in refugee camps in Italy in the 1980s. After the political changes in Poland, in 1989, only a few of them decided to return home (

Kaczyński 2016, p. 112). The phenomenon of non-return has a wider dimension and is quite widespread.

Castles and Miller (

2011) point out that these are the shortages of economic resources, and lack of guarantees for the preservation of human rights in the weak countries, run by despotic rulers, that often stand in the refugees’ ways to solving the problems which had resulted in seeking refuge and making the decision not to return home. Lack of such returns may also result from the motivation behind the migration, which is “often a part of the migration strategy aimed at facilitating a migrant’s ability to reach the destination country, or a legal stay in this country, and does not necessarily reflect the real motive of the journey” (

Okólski and Fihel 2012, p. 215). Host countries try to counteract such strategies, including organized deportations (

Sieniow 2016). The practice of avoiding or refraining from return to home countries can also be seen as the result of effective integration and refugees’ attachment to the country which gives them shelter. Integration policy, resulting from the need to ensure social cohesion and order in the host country, is also aimed at protecting newcomers from exclusion and marginalization. Effective integration policy, however, will hinder the tendency of newcomers to return to the countries they came from. This, in turn, changes the essence of seeking safe haven towards settlement immigration. In the situation of demographic decline in the host countries, this effect would be desirable, especially if it really resulted from an effective integration policy. The experience and practice of host countries show, however, that integration policy rarely brings the intended results. The real effect of the inflow of people from other countries is the growth in the size of immigrant communities, who live in their own, parallel worlds. There is a danger that ethnic enclaves will become ghettos isolated from the dominant society. In extreme cases this may lead to open expression of contempt and hostility towards the host country and its inhabitants (

Joahny 2016). Publicizing these phenomena in the era of the migration crisis shows that the reception of immigrants and refugees is increasingly accompanied by the atmosphere of uncertainty and fear (

Chodubski 2017, p. 14).

The demographic criterion refers to the composition and demographic structure by age and sex of the arriving individuals. Migrants are usually young people, whereas a refugee can be anyone who makes a successful attempt to escape in the event of a life threat in their own country. Therefore, the demographic structure of refugees should reflect the demographic structure of the population of the country from which the refugees arrive. In migration policy, this assumption manifests itself in taking into account the need for selective assistance, in order to first take care of the weakest among those who arrive. In the course of proceedings on granting refugee status, special protection covers the following groups of foreigners: minors staying within the territory of the Republic of Poland without legal or customary representative (unattended minors), victims of violence and the disabled, persons in an advanced age, pregnant women, single parents, victim of human trade, and sick persons.

One of the features of the mass migrant inflow of 2015 is the disturbance of demographic proportions. Among the people arriving in great numbers, the majority are young men (

Connor 2016, p. 12;

Hudson 2016;

Newsham and Rowe 2017). There were few women, children and elderly people. Some experts say, that “this is typical for migratory movements that the strongest people go first and ‘pave the way’. Women and children follow them later. It is normal, that even 75% of people on this refugee-migration route are men. Women with children remained in camps in Turkey or Lebanon. This is not an anomaly” (

Pędziwiatr 2015). However, this is not a typical situation. “The visual prominence of women and children as embodiments of refugeeness has to do not just with the fact that most refugees are women and children, but with the institutional, international expectation of a certain kind of helplessness as a refugee characteristic” (

Malkki 1995a, p. 11;

Malkki 1996, p. 388). The same aspect is underlined by Barry Stein (

Stein 1981). Current UNHCR data on the demographic structure of refugees, for example from Burundi, South Sudan or Myanmar, confirm that women are usually the majority (

UNHCR 2019). “Refugee migrations are more frequently composed of families, while immigrant migrations are more often composed of individuals” (

Hein 1993, p. 50). The fact that the demographic structure of those who arrive (by age and sex) does not reflect the demographic structure of the countries from which they arrive shows that we are dealing with an inflow that is not consistent with the ideal type of the refugee migration but it is closer to pioneer migration pattern.

Generally, refugees are expected to need help, because this stems from the basic tenets of refugee migration policy i.e., that they ought to be helped. In practice, however, refugees can also come from privileged groups and layers of their own societies, i.e., there can be wealthy and educated people among those who seek safe haven (this was the case during the revolution in Russia or France or during the expansion of Nazism in Germany, and in all cases of the typical exile (

Malkki 1995b). In the wave of refugees there can also be people who are physically and mentally strong enough to escape from the danger in their own country, and reach a safe country on their own. The only help such people need is to enable them to stay in a safe place (or country of their choice) as they are able to provide for themselves as long as they feel safe. They do not need to prove and manifest that they are helpless—because they are not. Policy towards refugees, however, seems to favor the development of the “learned helplessness” syndrome.

The information from refugee registration points is that the arriving refugees are well aware of the host countries’ preferences, and some of them want to receive help easily, by trying to pass as minors. “Three-quarters of age-tested asylum seekers who told Danish authorities they were children have been found to be older than 18” (

Sharman 2016). A Swedish pediatrician said that “he has examined several people that the migration agency has classed as children but that, according to his own professional opinion, almost 40% of them are in fact between 20 and 25 years old, and some of them even near their forties” (

The Local 2016). On the one hand, such events indicate the desperation of those who arrive, but on the other hand, they reflect the pressure exerted on organizations and institutions managing this migration, including the necessity to verify information on those applying for refugee status (

BBC News 2017). The described situations signal the difficulties, even when it comes to such basic data as the refugees’ age. It seems that the context of the migration crisis increases the despair of those arriving, who by all means try to enhance their chances of getting help.

Another element which allows to distinguish the refugee migration from other forms of migration is the neighborhood criterion. Moving to the nearest safe country, in the situation of security threat, is one of the typical features of refugee movements. Taking refuge in a neighboring or geographically close country allows for quick escape, but also for a quick return when the danger is over (

Malkki 1996). Searching for shelter in the neighboring country thus strengthens the trait of the ideal type of the refugee flow, such as the temporary nature of the stay. However, in the era of the present migration crisis, seeking refuge in neighboring countries ceased to be a common practice and rule. This is a very meaningful fact, that the essence of the migration crisis is the inflow of non-European individuals to Europe. These people do not escape to the country on the same continent, but choose the option of a further journey. Increasingly, the direction of these movements is determined by other than geographical factors, e.g., by socio-cultural links and networks.

3. The Scale and Specificity of the Refugee Inflow to Poland

The arrival of asylum seekers in Poland is a relatively small-scale phenomenon. As calculated by experts from the Migration Research Committee of the Polish Academy of Sciences, since the signing of the Geneva Convention by Poland, in September 1991, by the year 2016 more than 135,000 foreigners had applied for refugee status, “of whom only approx. 4.5 thousand (3.5%) gained the opportunity to settle in Poland, and about 15,000 were granted temporary protection or temporary permit for tolerated stay. It is estimated that a significant proportion of people entitled to stay in our country left its territory” (

KBnM 2016). However, in each subsequent decade, an increase in the number of those applying for protection in Poland, and the number of those who are granted such protection as refugees, can be noticed (

Kosowicz and Maciejko 2007). For example, in 1993 applications for refugee status were submitted by 822 people (61 people were granted the status), in 2003 6906 people applied for refugee status (245 people were granted the status), in 2013 there were 15,253 people who applied for refugee status, and it was granted to 427 people. The growing number of refugees is accompanied by a drop in the percentage of positively processed applications: in 1993, refugee status was granted to 7.4% of the refugees, in 2003 to 3.5%, and in 2013 to 2.8% of those who applied. This means that obtaining refugee status in Poland is becoming more difficult. At the height of the European migration crisis, there was no rapid increase in the inflow of refugees to Poland. According to the Office for Foreigners, in 2015 applications for the refugee status were filed by 12,325 people (the status was granted to 348 people, i.e., 2.8%), in 2016, 4502 applications were submitted by 12,321 persons, of which only 108 people were granted the refugee status (i.e., 0.87 %); in 2017, 2226 applications were submitted by 5078 persons (the status was granted to 150 people, i.e., 2.95%). The immigrants from countries involved in the European migration crisis were not represented in large numbers in Poland. Refugees from Syria accounted for only 2.4% (295 people) of all new arrivals, while at the same time in EU countries, refugees from Syria accounted for 30% of the asylum seekers (

Martin 2016, p. 309). However, the likelihood of obtaining refugee status in Poland was greater in case of people from Syria than in the case of foreigners from other countries. In 2016, out of the total 108 positive decisions issued, 40 decisions (37%) concerned people from Syria. In 2017, this percentage dropped to 11%. Official data on refugees in Poland show that refugees representing the wave of “migration crisis” (e.g., from Syria) were granted refugee status in Poland much more often than refugees from other countries. Therefore, it can be said that, regardless of the politicians’ declarations, Poland was open to receiving refugees who came with the wave of the “migration crisis”, although they did not come in great numbers.

The gender structure of the people applying for refugee status in Poland does not show strong masculinization. In 2015, refugees from 53 countries (4636 women and 4280 men) filed applications for refugee status in Poland. Out of the 53 countries, there were 41 countries in case of which the applications were filed more often by men, including Ukraine (1248 men and 1057 women), Syria (190 men and 105 women), Georgia (201 men and 193 women) and Armenia (98 men and 97 women). The prevalence of women among refugee applicants concerned only 9 countries, including Russia (4143 women and 3846 men), Tajikistan (287 women and 254 men) and Kyrgyzstan (80 women and 67 men).

The characteristic feature of the refugee inflow to Poland in the peak period of the migration crisis is that it consisted mainly of people from neighboring countries. In 2015, the majority of those applying for refugee status came from the Russian Federation—7989 (64.8%) and Ukraine 2305 (18.7%). Migration from Russia, which has been at a high level for many years, concerns the Chechen population, who do not live in the immediate vicinity of Poland. For Chechens, however, Poland is the first safe country to which lead already paved paths. What is significant about this nation is that they often treat Poland as a transit country (

Cieślińska 2005), migrating sooner or later to Germany or other richer countries. This natural phenomenon to some extent explains the reluctance of Polish authorities with respect to the idea of relocation of refugees.

4. Social Reactions to Relocation Plans for Refugees in Poland

The European migration crisis has revealed a dichotomous and, in practice, even a conflict-generating division within Polish society, into those who support the idea of accepting refugees in Poland and those who oppose it. Surveys, which have been conducted by the Public Opinion Research Center (CBOS) since May 2015 indicate polarization of public opinion on this point. At the same time, there has been a systematic decrease in the percentage of respondents who have no opinion on this subject, in favor of the rise in the proportion of opponents of accepting refugees in Poland. In May 2015, the “difficult to say”, answer was given by 14% of the respondents, whereas a year later it was 7% of the respondents, and in 2017 it was only 5%. The opponents of accepting refugees initially (May 2015) constituted 53% of the surveyed people, and the supporters constituted about 33%. Two years later (April 2017), the opponents constituted 74% of the respondents, and the supporters only 22% (

CBOS 2017, p. 2;

Bachman 2016).

The respondents’ views regarding the admission of refugees were significantly related to their political preferences. Platforma Obywatelska [Civic Platform]—the ruling party in 2007–2015—had the highest percentage of supporters for the “open door” policy. However, many respondents voting for this party were against the relocation of refugees. There were almost as many supporters as opponents of welcoming refugees in Poland. Respondents voting for the ruling party—Prawo i Sprawiedliwość [Law and Justice]—were almost unanimous in their reluctance to accept refugees arriving in Europe (see

Table 1).

Other differences between supporters and opponents of receiving refugees in Poland were related to their place of residence, education level and income: “In favor of the admission of refugees, relatively most often, are: the inhabitants of biggest cities (39%), people who have higher education (33%), and people with the highest per capita income (29%). The opponents of relocation are most often: the youngest respondents (87% of the opponents among people aged 18–24) and people who participate in religious practices every week (77%) or more often (86%)” (

CBOS 2017, p. 3).

It seems that the opponents of the “open door” policy belong to the more excluded rather than to the privileged groups in the Polish society. The negative attitude towards refugees may, therefore, arise from fears of their situation, social security and life prospects portrayed as getting even worse when the help and attention of the Polish State is directed at newcomers who need support. In Poland, social reactions to refugees can be considered as a manifestation of “moral panic” (

Cohen 1972), like in Hungary (

Sik and Simonovits 2019). Actually, the case of Poland is even more related to the moral panic phenomenon because Poles learned about the European migration crisis mainly through mass media and then began to fear the perceived consequences of accepting immigrants and refugees of a different religion and culture. It should be noted, however, that the concerns and fear of newcomers were, to some extent, intertwined with compassion and attempts to understand this situation (

Cieślińska 2017;

Jaskułowski 2019). The 2015 parliamentary elections were won by the parties who declared they would protect Poland from the migration crisis and the inflow of immigrants and refugees. Three years later, in local elections, migration issues turned out to be much less important. In all major Polish cities (including Warszawa, Lublin and Białystok, where refugee centers were located) the winning presidential candidates supported the “open door” policy, although they usually did not emphasize this in their campaigns (

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights 2018).

5. Refugees and Health Issues

In the course of the election campaign, one of the arguments used by the opponents of the “open door” policy was the refugees’ health condition and possible epidemiological threat. It needs to be said here that this fear of health problems stems from the very fact that many people arrive in one place and live together sharing a relatively small space, which increases the disease risk. In addition to that, the pre-migration situation, difficult journey, separation from family, stress and often trauma of staying in a new place, accompanied by hostility, detention and an uncertain future may affect not only the infectious, communicable, non-communicable or chronic diseases but also the mental health of these people (

Hunter 2016;

Fotaki 2019) and especially the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

Baranowska 2016). The symptoms of health problems may also appear in future, adding another serious issue to the system of medical care in the country of their settlement (

Hunter 2016). Therefore, the host countries should adopt certain courses of action to take care of refugees’ mental and physical condition (

Perna 2018). One idea is to have special interdisciplinary teams, sensitive to cultural diversity (

Pavli and Maltezou 2017) to consult and control refugees’ health and, at the same time, facilitate their integration.

In 2015, the leader of the PiS party, Jarosław Kaczyński, drew attention to this problem by recalling examples of countries in which: “there are already signs of emergence of diseases that are highly dangerous and have not been seen in Europe for a long time: cholera on the Greek islands, dysentery in Vienna (…) various parasites, protozoans, which are not dangerous in the bodies of these people, but can be dangerous here. This does not mean discriminating against anyone (…) but it needs to be checked, said Kaczyński” (

Pilonis 2015). Polish media raised the subject, contributing to even greater polarization of society. Apart from the campaign and political preferences in this discussion, Poles represented two extreme attitudes: one of approval for multiculturalism, tolerance and openness, and the other full of fears concerning the general health security of the country. The first group quoted the examples of Poles who, as tourists, visit exotic countries and are not subjected to health checks on crossing the border; no additional vaccinations are required. The same people argued that refugees who are used to contact with diseases are already immune, so the threat is not big. In their rhetoric they even resorted to comparing the denial of entry to Poland, on the basis of the likelihood of spreading diseases, to the Western states’ closing to the Jewish community on the eve of the outbreak of the World War II, indicating the tragic consequences of this attitude. The second group was dominated by fears caused by the cases of these diseases known in other European countries. Great attention is paid to one of the most serious infectious diseases of the 21st century—AIDS, as the proportion of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive migrants reflects the epidemiological pattern of their country of origin (

Castelli and Sulis 2017). In Poland there was the case of a Cameroonian, Simon Mol, who was granted refugee status in Poland long before the onset of the migration crisis. He received the financial, medical and social support he needed. In 2007, the media reported that this man intentionally infected Polish women with HIV (

Gietka 2018). This event, an example of cynicism and superstition, stirred up the public opinion and, along with the rhetorics of the politicians, it significantly poisoned the atmosphere around the issues of reception of refugees and health security of Polish citizens.

6. Refugee Center in Białystok

With nearly 300,000 inhabitants, the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship, known for its ethnic and religious diversity, belongs to a few Polish cities (besides Lublin and Warszawa, and earlier also Łomża) where refugee centers were located (

Łaciak and Segeš Frelak 2018). The city was selected for the analysis because of its almost three decades of experience with hosting refugees and adapting multicultural policy in different spheres of the city’s life. In Bialystok, cultural and ethnic diversity is a currently experienced fact. Apart from Poles, the largest ethnic and religious group is of Belarusians, and the second religious group after Roman Catholics are Orthodox Christians (

Sadowski 2006). There is also a refugee center in Białystok, which welcomes refugees, who are mostly followers of Islam. Białystok is located in the proximity of the eastern border of the European Union, and by the same token, it is the most exposed city as far as the inflow of refugees from non-EU countries is concerned. The first wave of refugees reached Białystok in the early 1990s, before the refugee center was established. At that time, most of them were Armenians who came to Poland with entire families. The Armenians fled their country from the effects of the war against Azerbaijan, the destruction caused by the earthquake, and from unemployment and poverty. In Bialystok, they rented, at their own expense, cheap rooms to live in, and found gainful employment, mainly in trade. They were struggling with a number of problems resulting from illegal business activity (lack of work permits) and problems with the legality of the residency. Applying for refugee status was an opportunity for them to settle their matters right (

Cieślińska 1998). However, the likelihood of them obtaining refugee status was close to none. The data show that in the years 1992–2008 there were 5321 decisions issued on granting refugee status to Armenians but only 13 decisions (i.e., 0.24%) were positive and 4415 (i.e., 83%) negative; 883 cases (i.e., 16.6%) were discontinued and 10 decisions (0.2%) were related to tolerated stay (

Marciniak and Potoniec 2008, p. 115). This shows that gaining protections in Poland was extremely unlikely for Armenians. Some of them sought other ways to legalize their stay in Poland (e.g., by entering into marriages with Poles).

Another group of foreigners, who (similarly to the Armenians) came from the Caucasus region, with entire families, were the Chechens. Their arrival to Białystok was associated with obtaining accommodation in the refugee center launched in October 2000. It was the same hotel that had previously rented rooms to the Armenians. The situation of the Chechen population in Bialystok was diametrically opposed to the situation of the Armenians. They came to a hotel—a refugee center—where they had their means of livelihood guaranteed. Despite these more favorable conditions, as compared to the situation of the Armenians, the Chechens experienced a number of deficiencies and inconveniences in that place (

Cieślińska 2005). In 2001, one more hotel, of a slightly higher standard, was rented to refugees (e.g., with bathrooms in their rooms), which became the main and, with time, the only place where persons awaiting the decision on refugee status stayed. The deserted building of the first refugee center was adapted to social housing for the evicted residents of Białystok. According to the CBOS survey, the respondents with the lowest income and social position are also the chief opponents of receiving refugees (

CBOS 2016a,

2016b). Perhaps they can see, as in Białystok, that refugees are provided with better conditions of living than the impoverished, native people of Białystok, who are also in an extremely difficult situation.

Social assistance of the country which hosts refugees is of great importance not only for the foreigners seeking protection, but also for the receiving community. In Białystok, owing to the fact that the basic needs of the people who stay in the refugee center are provided for, the economic and social security increases. However, this solution does not favor integration with the local community. The example of the Armenians, who were not provided with financial help, shows that this fact motivated their integration with Polish society: they learned Polish, they sent their children to Polish schools on their own initiative, they undertook service activity (mainly in trade) and established personal contacts with the local people. At the same time, the Chechens, taking advantage of the support of the Polish state, tended to isolate and withdraw more often. Scientists who work on security issues have serious objections regarding maintenance of refugee centers during the European migration crisis: “These centers do not help at all, at least not in Białystok, and Białystok centers are reported to have detained the supporters of the so called Islamic state. These centers help nobody. They actually isolate those people from the local community and lead to trouble and difficulties with people who cannot find a place for themselves” (

Boćkowski 2015).

When the refugees’ stay in the centers is prolonged for years, lack of integration may result in the creation of an isolated ghetto. In Białystok, the city authorities officially support financially the projects and campaigns that promote integration, multiculturalism, and tolerance towards migrants and refugees. Originators and implementers of these initiatives are usually active, non-governmental organizations in the city (

Wciseł 2015). Admittedly, one can get the impression that these initiatives do not bring any visible results, but they constitute some form of the process of familiarizing the city’s inhabitants with the idea of a multicultural society whose characteristic feature is the presence of immigrants and refugees.

7. Shaping Public Opinion on the Relocation of Refugees

The so called migration crisis was caused by the arrival of refugees from Syria and North Africa reaching Europe. The intensification of persecution of Christians in these regions, was frequently signaled by Aid to the Church in Need (ACN) organization in biannual reports

Persecuted and Forgotten? (

Pontifex and Newton 2011), but this voice was hardly heard. The fact that the mass media gave spectacular examples of difficult situations of numerous refugees reaching Europe (

Park 2015) influenced the change in previously indifferent attitudes towards these problems.

According to the UNHCR recommendations, a fair share of responsibility is the key to controlling the migration movements, and EU countries will have to develop a system that will oblige individual EU countries to take in a certain percentage of people in the refugee procedure.

The subject of relocation became an element of public debate also at the local level. Białystok Local Television, in a popular program

Bez kantów (presented on 14.IX.2015) issued a special edition devoted to the European migration crisis (

TVP Białystok 2015). Experts and social commentators were invited to the studio. The recordings of the opinions of the leaders of the main political parties in the Podlaskie Voivodeship were included. Their statements reflected differences among local political parties on this matter. Below are the selected, most characteristic fragments of opinions presented to the viewers of Białystok local television in the order in which they were broadcasted:

“Since 1990 Poland has received over 90,000 refugees from Chechnya and we managed, there were no problems. (…) It is enough to want to do it (…) we are obliged to show solidarity with Europe, the key to success is the cooperation between the government, self-government and organizations.

(PO, Robert Tyszkiewicz)

Not giving in to blackmail of other states (…) we should take care of our citizens’ security (…) Of course, we cannot avoid helping the persecuted Christians, but we must consider it in reference to providing adequate conditions for residence and work, and support them as much as possible.

(PiS, Krzysztof Jurgiel)

We should have something to say about refugees. (…) The European Union will make the selection—but on what basis? Scientists, teachers will go to England, France and Germany, and who will come to us? You need to look at this aspect. (…)

(PSL, Mieczysław Baszko)

The most important thing is to stabilize the situation in North Africa. (…) Every day shows that the problem of migrants is growing, this river of migrants is growing wider and will flow for long, long years. This is not a matter of 500,000 or 1 million of people. This could potentially be 15 million in the coming years.

(Zjednoczona Lewica, Krzysztof Bil-Jaruzelski)

(…) women and children stay where the war is. However, adults, strong men escape (…). We should not succumb to any blackmail and tell the West directly that if the West caused instability in the North African region, then the West must bear the cost of these actions and introduce a strategy of helping these people where they are, in their home countries. However, we should not take everyone in, because it simply threatens the whole of Europe, including Poland.

(KWW Kukiz’15, Adam Andruszkiewicz)

(…) this is the result of a wrong and disastrous EU policy. (…). These are not refugees but ordinary social immigrants. (…) if 70% of them are men in their prime—you cannot talk about refugees. Young people in their prime will settle down in a country, e.g., in Germany or Austria, they will be trying to bring their families from there, or maybe even will not, because, as you know, the Islamic state has announced that it will put terrorists among 500,000 of those who sail to Europe on boats.

(KORWiN, Szczepan Barszczewski)

The quoted words not only reflect but also shape atmosphere around the migration issues and the anticipated increase in the number of refugees. Some of the local politicians tried to convince the public that the reception of refugees would be as smooth as it has been so far (i.e., almost unnoticeable). Others saw a need for intervention in the countries of origin of the refugees. Still, others suggested the need to adopt the “delaying tactic” and selective reception of refugees (“the persecuted Christians only”). In some of the statements there were fears about the perceived inflow of uneducated and unprofessional people. There were also voices presenting a clearly negative attitude towards the possible reception of the fleeing people.”

8. Conclusions

From a sociological perspective, the discussion about the migration crisis would not be complete if no attempt to determine the features of the “ideal type of asylum seekers inflow” was made. The ideal type, as understood by Max Weber, does not appear as pure phenomenon, but it is a useful tool for studying real phenomena. In the case of the inflow of refugees, the application of the “ideal type”, developed on the basis of existing practices, allows to perceive and analyze these inflow features which are incompatible with the ideal type. The year 2015 showed that when such incompatibilities appear, they quickly become grounds for a situation of crisis. Therefore, a series of phenomena and events that occurred in that period is referred to as the migration crisis or refugee crisis. At the same time, it is worth remembering that changes in the characteristics of the inflow have further consequences, including a change in the meaning and role of immigrants and refugees in the host society (

Newsham and Rowe 2017).

Secondly, the analysis showed that the reactions of Polish society to EU policy on the relocation of refugees are divided but they represent certain patterns: they may be classified according to political preference—the right-wing electorate is usually against receiving refugees—but also the demographic features, such as: place of residence, education and income. Generally, though, the apprehension may stem from fears of Poles’ own situation—social security and life prospects—being endangered by the newcomers. The presented analysis of the ongoing discussion in the public media space shows that the issue has been still evoking strong emotions in the Polish society.

Thirdly, the migration crisis led to the attitude towards the reception of refugees in Poland becoming an important part of the election campaign for the Polish parliament in 2015. The successes of political parties whose representatives showed their reluctance towards accepting refugees and immigrants showed that Polish society, despite the rich experience of multiculturalism (historical and referring to emigration), is afraid of the arrival of non-European citizens. This is confirmed by the results of public opinion polls, see, e.g., (

CBOS 2017). We point out that many Poles went to work abroad and know what it means to live in a foreign country but it is difficult for them to accept refugees who do not undertake paid work and expect material and financial support from their host society. In addition, the recent Polish migration experience of living and working in multicultural and multi-ethnic countries of the European Union, like the United Kingdom, could have negatively affected the perception of refugees and immigration: “In Lublin and Białystok, the interviewees often referred to the opinions of their acquaintances or relatives working abroad who have contact with representatives of different nations, including refugees from the Middle East, and emphasized their negative attitudes to accepting such refugees in Poland or, generally speaking, in Europe” (

Łaciak and Segeš Frelak 2018, p. 21).

On the other hand, the policy of openness to welcoming people from other countries rarely is an altruistic activity. Most often the reasons are related to the implementation of the host countries’ explicit or hidden interests (

Michalska 2016, p. 65). For example, the current migration crisis coincides with the demographic crisis in Western countries. Starting the inflow of young people (immigrants and refugees are usually young) may moderate and slow down unfavorable demographic processes which would lead to the depopulation of Europe (

Park 2015, p. 6).

The “open door” policy seems to be consistent with the idea of a multicultural society. In practice, however, the experience of multiculturalism is difficult. The case of Białystok also shows that providing social assistance to refugees (including placing them in refugee centers) is not conducive to their integration with the host society. At present, no negative effects of non-integration are observed, as the scale of the inflow is still relatively small and the phenomenon is characterized by relatively high compliance with the ideal type of the refugee inflow.