1. Introduction

In early 2017, the English-speaking academic world celebrated the publication of a book written by Manfred Steger and Amentahru Wahlrab. Reviewers have emphasized that it is a much-needed foundational text of a new, emerging discipline, at this time unhesitatingly named ‘global studies’ (GS), after decades of alternating and joint name uses, such as ‘globalization studies’ and ‘global and international studies’. The authors did excellent work in tracking down the intellectual roots of global studies, delimiting its area of study, and discussing its methods, and the book can easily pass all traditional academic scrutiny. Yet the specificity of the subject matter invites one more question: to what extent does the work embody an American (or Western, or Global-Northern) outlook as opposed to a genuinely global (or culturally unbiased) outlook?

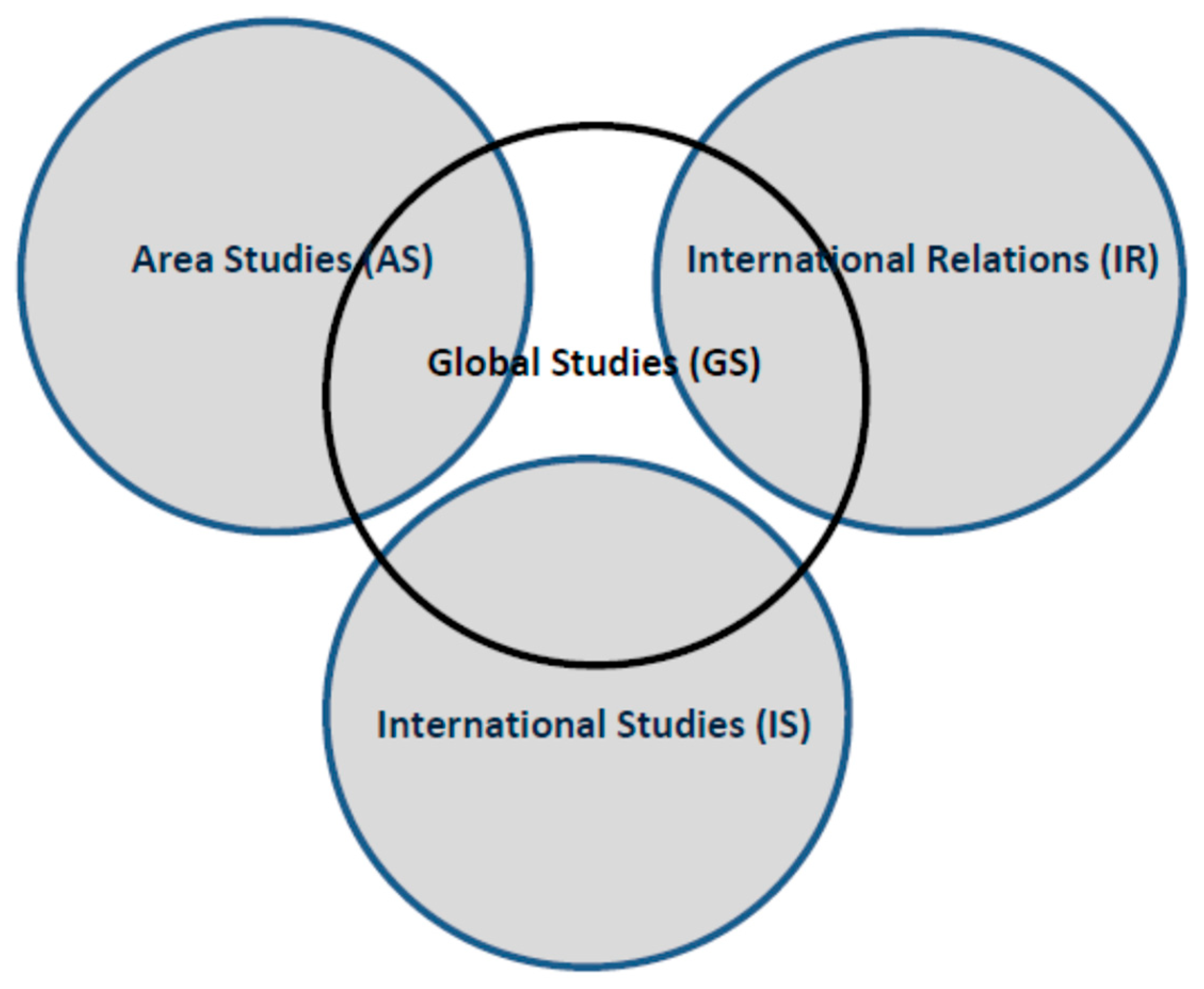

To their credit, the authors made efforts to address the Westernist bias of their field, but having some awareness of bias and successfully transcending it are two different realities. The book’s bibliography covers English titles only, even if some ‘foreign’ classics such as Gramsci and Lyotard made their way into it. We particularly miss a reference to Alexander Chumakov, whose selected writings on globalization were published in an English volume in 2010 with the recommendation of Roland Robertson and William Gay, among others. Yet Chumakov’s philosophical perspective came obviously at odds with the epistemological genealogy delineated by Steger and Wahlrab, who, following

Mittelman (

2002), construct GS at the intersection of area studies (AS), international studies (IS), and international relations (IR), as in

Figure 1.

And historically this is quite accurate for the U.S. literature, with quite unfortunate consequences for global studies’ ability to transcend certain biases of Western academia. This ancestry tends to confine GS to an ‘international’ vision. Steger and Wahlrab argue for the merits of ‘transdisciplinarity’ as opposed to ‘interdisciplinarity’ and ‘multidisciplinarity’. The ‘inter’-prefix is believed to reinforce, rather than efface, boundaries.

Robertson (

2010) also argues that global studies should be transdisciplinary, “or post-disciplinary, anti-disciplinary, cross-disciplinary and, most unfortunate, inter-disciplinary. I reject the latter because it actually has the consequence of consolidating disciplinarity, rather than overcoming it” (pp. 5–8). We would make the case for ‘transnational’ as opposed to ‘international’ and ‘multinational’ (‘supranational’ would be the most preferred word, had this term not been appropriated by European Union studies). Emerging from three disciplines seriously tinted with methodological nationalism, can we trust global studies to be more than ‘international’ or ‘multinational’?

This paper does not aim at a criticism of Steger and Wahlrab’s book, though it will articulate a few ideas about how it could become more global and less American. It aims at an analysis of the knowledge domain in which Steger and Wahlrab placed global studies, configured to capture socio-political thinking on issues transcending the nation-state. At a deeper look, this domain reveals a strong bipolarity. It is clearly dominated by international relations stubbornly promoting the primacy of nation-states, while an antithetical vision and ethos of global connectedness try to gain traction.

The first section of the paper will detail these statements about the state of the field with four disciplines, bringing evidence for the supremacy of international relations in it. The second section will analyze IR’s entrenched biases, which were transmitted to the nominally autonomous international studies and area studies. The concluding part will make the case for unifying the field under the primacy of global studies.

2. Mapping the Field

2.1. Theorizing beyond the Nation-State

The first decades of U.S. political science, as constructed by the Chicago School during the Progressive Era, had shown little intellectual interest in international politics. Political science’s ‘external affairs’ branch, international relations, was initiated in the U.K. in 1919, and in the U.S. it established itself as an academic discipline after Hans

Morgenthau’s (

[1948] 1993) joining the University of Chicago, where he co-founded the Committee on International Relations. The work of this first U.S. graduate institution came to fruition in the 1940s with the publication of Quincy Wright’s, “A Study of War” and Morgenthau’s “Politics Among Nations”.

Yet, beginning with the 1940s, IR’s growth became exponential, and it attained a serious influence on other fields and disciplines. Most presidents of the International Studies Association (ISA) thus far have been political scientists working in the IR field. In exact numbers, out of 57 presidents, 53 were political scientists, and 50 were Americans, that is, educated and working in U.S. universities

1. ISA’s flagship journals are monitored for impact as IR journals and have a very good placement on that list. Of 74 ISA partner organizations, 33 are in the field of political science, 18 have ‘international studies’ in their name (being country-wide or regional IS organizations), and 23 are of another nature, such as specific area studies, social studies, and honor societies. After the Toda Institute for Global Peace and Policy Research had changed its name to Toda Peace Institute, none of the partner organizations have ‘global’ in their names any longer. Faced with this evidence of international studies’ dependence on international relations, it is difficult to portray IS other than as a colony of IR. In fact, Steger and Wahlrab also use harsh words to shed light on this dependence: “founded in 1959 largely by disaffected American political scientists, the ISA embraced a methodological nationalism that served the geopolitical strategies and priorities of the First World in general, and U.S. hegemony in particular” (p. 8).

Sadly, similar considerations apply to the field called Area Studies as well. It may also be said to have grown up in a ‘national security environment’, with funding provided by the U.S. government and private foundations promoting values that make the world more hospitable to Western economic goals. Furthermore, the major change of the Area Studies field, when it made a determined effort to switch from individual country studies towards studies on larger geographical scale and incorporating more ‘globalism’, came in the 1990s under the push of neoliberal economics’ interest in globalization.

In this context, we may wonder to what extent is global studies today independent of IR? The main challenge for GS’s independence is not the delimitation of its subject. This has traditionally been globalization, the many ways in which events in one area of the world influence events in other parts of the world. Yet IR’s entrenched methodological nationalism, which has deeply penetrated IS and AS, as well, are serious hurdles to a global perspective and methodology to take off. We are much less optimistic about the accomplishments of global studies within U.S. academia than Steger and Wahlrab, for instance.

First of all, the U.S. higher education system does not recognize ‘global studies’, as such. The College Board’s college search system uses a double name: ‘international studies/global studies’. As of June 2017, the search engine found 327 such programs, of which 297 were offered by American not-for-profit four-year institutions. Yet at a closer look, some of the programs were actually neither IS nor GS, but ‘international business’, ‘international management’, ‘international communication’, and so on. We did not discard these from the sample, but they occur in the ‘none of these’ columns of

Table 1. Eighteen programs had names different from, but similar to either IS or GS, they also received a separate column

2. The end result is that programs of IS outnumber programs of GS by almost 2:1. It is only 77 + 5 = 82 four-year programs which endorse the Global Studies nomenclature.

Moreover, 82 programs do not mean 82 global studies departments. About half of the 297 programs in the list are run as inter-departmental programs, and many of them are housed in departments such as social sciences, humanities and languages, and education. Based on the institutions’ website, we could identify 33 International Studies departments and 23 Global Studies departments.

As for graduate degrees,

Table 2 shows that there are 16 U.S. institutions offering degrees higher than bachelor’s in either IS or GS, and 14 culminate in Master’s. Only two offer a doctorate: UCSB’s is a clear-cut global studies PhD, while UMass’s is a ‘similar name’ program, actually rather in political science than in GS.

These numbers should be interpreted against the background that there are about 3000 public and private non-profit four-year institutions in the U.S., thus it is less than 10% offering any version of a program that may be classified as IS or GS. Further, the four-year IS/GS programs are more likely to occur in private institutions (at the rate of 179 to 116), and private institutions are somewhat more likely to call their program ‘global’ than public institutions. These asymmetries are important because public institutions tend to be larger than the private non-profits. They educate approximately twice as many students every year. The typical environment for an IS/GS bachelor’s program to occur are the small liberal arts colleges. On the positive side, the IS/GS graduate degree granting institutions are, with one exception, all public.

Overall, the U.S. educational landscape does justice to Mittelman’s map of GS at the intersection of IR, IS, and AS, even if the whole picture should include the fact that the entire field is clearly dominated by IR and its worldview. The associational and publishing landscapes, though, suggest a different disciplinary influence, which allows for the hope of a truly global vision. As a matter of fact, there is a Global Studies Association, even if it is much younger, smaller, and less known than the ISA. It was established in 2000 in the UK and continued to remain heavily British, though in 2002 it developed a North American chapter, as well. GSA was established and mainly headed ever since, by sociologists. GSA is involved with three journals:

- i

Global Networks: A Journal of Transnational Affairs, a quarterly published by Wiley on behalf of GSA and the Globalization Studies NetF3work.

- ii

Globalizations, published by Taylor & Francis, sponsored by both ISA and GSA. The journal is ranked both as an IR publication (where it is 32/85) and as a Social Sciences Interdisciplinary publication (33/95). In 2013, Globalizations (vol. 10, issues 4 and 6) hosted a high-profile debate on ‘what is Global Studies’? with the participation of Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Kevin Archer, Barrie Axford, Mark Juergensmeyer, James Mittelman, Benjamin Nienass, and Manfred Steger.

- iii

International Critical Thought Journal, published by Taylor & Francis on behalf of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The international editorial board includes GSA’s North American chair, Jerry Harris. The board also includes Immanuel Wallerstein and Alexander Buzgalin, a colleague of Chumakov.

The 2000s brought about a number of encyclopaedias on globalization and global studies; we may notice a competition among publishing groups for having the last say in this increasingly fashionable field

3. Some of them upgraded their first trial to a more prestigious edition a few years later, for instance, the five-volume Wiley

Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization edited by George Ritzer in 2012 was preceded by a

Blackwell Companion to Globalization edited by him in 2007. Sampling out this volume from the group of publications, we looked at the discipline and nationality of the authors (

Table 3). Though the Anglo-Saxon dominance is clear, the authors tend to be sociologists, rather than political scientists.

Sociology’s predominance in certain associations and publications suggests that other global studies are possible, some of them hopefully liberated from methodological nationalism. There are some promising exceptions in U.S. education, as well, as the sociologist-anthropologist instructors of global studies at UC Santa Barbara, Eve Darian-Smith and Philip McCarty, in their book published six months after the Steger and Wahlrab volume, set out to outline a global transdisciplinary framework explicitly meant to transcend “the dominant state-centered thinking that still prevails in the Euro-American academy” (p. 175). Yet Darian-Smith and McCarty’s vision of global studies does not transcend the idea of an empirical study field

4, where the global or transnational perspective is achieved on a casuistic basis, within each study or study-cluster, such as cross-border studies (e.g.,

Amelina et al. 2012).

As global studies are inherently multi-disciplinary, one may expect methodological fallacies to be unevenly distributed in function of the disciplines involved in the queries.

We think that the most hazardous methodological challenge for a field of study meant to handle global issues is methodological nationalism. Since the 1970s, when the term was coined by Anthony Smith, there has been considerable agreement about the nature and importance of this fallacy.

Wimmer and Schiller (

2002) defined it as “the assumption that the nation/state/society is the natural social and political form of the modern world”.

Chernilo (

2006), who disagrees with them in the operationalization of the concept, still adopts an almost identical definition: “methodological nationalism can be defined as the all-pervasive assumption that the nation-state is the natural and necessary form of society in modernity; the nation-state is taken as the organising principle of modernity”. Wimmer and Glick Schiller portray methodological nationalism as a multi-faceted phenomenon, which comes in several variants, such as the national framing of modernity; the naturalization of the nation-state; and the reduction of the analytical focus to the boundaries of the nation-state. All these variants manifest themselves differently in different disciplines, for instance, “international relations assume that nation-states are the adequate entities for studying the international world” (p. 304). Yet thus far it was only sociology making a strong case against methodological nationalism. Not as if sociologists would fully agree about the depth and extent of its impact on social theories, let alone the ways to overcome the fallacy. For instance,

Chernilo (

2006) takes an issue with

Beck’s (

2007,

2013) project of replacing nation-state centered perspectives with a view called ‘cosmopolitan’, because Chernilo aims at overcoming methodological nationalism through demonstrating that “in modernity, the nation-state has been historically opaque, sociologically uncertain, and normatively ambivalent”. Disciplines outside sociology happen to embrace projects that do not address the problem of methodological nationalism, for instance,

New Global Studies, a journal founded in 2007 by MIT historian Bruce Mazlish, promises to interpret “globalization with a historical and sociological angle as opposed to history or sociology with a global angle”

5. This sounds as if, for some scholars involved with this field, global studies are global in virtue of the phenomenon they study, and our vision and methods do not need to follow suit.

The next section will focus on only one discipline, but on one that has influenced global studies through multiple channels. We have to admit that our portrayal of the trans-nation-state field of study, focused on international relations and sociology, does not do justice to several other disciplines contributing to the discipline of global studies. Yet we argue for the importance of theorizations, and of all contributing disciplines, it is IR and sociology that are the most likely theory-builders. We wish there were alternative influential theory-builder schools, such as historical sociology, which, with Barrington Moore, Charles Tilly, and Theda Skocpol, for instance, struck a fine balance between acknowledging a nation-state based world and the impact of processes that go beyond the nation state. They influenced comparative politics, but had no real impact on IR, in which dependency theories and

Wallerstein’s (

1974) world systems theory also remained marginalized curiosities. The contention we develop is that methodological nationalism cannot be overcome without allowing for the causal efficacy of factors other than nation-states, and this takes a theory doomed to collide with IR. Our example for such a theory is Chumakov’s, which, like the dependency and world system theories, focuses on the economic domain. We are aware that it is unlikely that it will be Chumakov’s theory that becomes a challenger of the IR-inspired theorizations in the mainstream global studies field, with its center of gravity still heavily in the U.S., but we do think that similar theorizations should be mainstreamed.

2.2. IR, Where Methodological Nationalism is Rooted in Political Nationalism

Critics of methodological nationalism tend to point towards the occurrence of this fallacy in the field of social theory, in general—missing the point that there is an entire, influential discipline that is almost entirely constructed on the assumption that humanity is inevitably and unchangeably divided into nation-states, and that nation-states are thus the most important and most appropriate forms of organization. International relations, as it emerged around the Second World War, seems to have been locked into this perspective for all of its history, despite past and ongoing paradigmatic foundational debates, which lately shed light on related biases such as Westernism.

In fact, IR’s most consequential bias seems to be the over-valuation of nation, nation-state, and national allegiance, because these assumptions are shared by the mainstream scholarship in the field. More exactly, these are the shared assumptions of the three most influential IR paradigms, and they are challenged only by some critical paradigms, which are, almost by definition, at the periphery of the discipline.

Yet IR may be criticized for much more, and several other epistemological and ethical issues may be shown to be related to the basic worldview of the globe as a collection of nation-states. This section will elaborate on tracing back the pervasiveness of methodological nationalism to the predominance of U.S.-based scholars in IR, and will also point out some seemingly related biases, such as the neglect of bridge-laws, which connect between different levels of phenomena, and a penchant towards simplifying explanations, which lead to poor predictions and even in principle unfalsifiability.

2.2.1. International Relations’ State and Anarchy Model

IR is a quite typical American product, and all study of its methods should take this into consideration.

First of all, the ‘classics’, the originators of the three main paradigms—realism, idealism, and constructivism—that always make their way into every IR textbook, were all born as or became U.S. citizens.

Second, the discipline’s main cleavages and foundational disputes remained within the confines of U.S. academia, at least up until the 21st century. Most notably, the liberalism versus realism controversy, and constructivism’s challenge to both, pitted Americans against Americans, with a few British trying to carve out middle grounds between the parties rather than determinedly siding with any of them (

Carr 1939;

Bull 1977).

Third, the epistemological ideals of international relations have become unreservedly reflective of the positivist trend conquering the post-World War II social disciplines, even if liberals favored statistical analysis while realists swore by game theoretical modelling. Neither statistics nor game theory is as American as the IR scholars’ unwavering support for their rigorous application to historical events, despite the general trend of generations of historians either to compromise with or outright surrender to idiographic methods.

And fourth, both main IR paradigms, with their ramifications, and also most of constructivism, embody a view of the global social world that is deeply rooted in the United States’ self-image and is solely compatible with the American national ethos. The briefest summary of this claim is that IR’s ‘international’ relations are, actually, ‘inter-state’ relations. This is very categorical in realism and less obvious, but fully pervasive in liberalism. Constructivism has developed two main branches, which may be termed ‘statist’ (Alexander Wendt, Peter Katzenstein) and ‘social’ (John Ruggie, Nicholas Onuf, Friedrich Kratochwill, Margaret Keck, Kathryn Sikkink). IR scholars in the social constructivism perspective, like those in other non-orthodox (‘critical’) perspectives of the field, such as Marxism, feminism, and postmodernism, tend to challenge the dominant paradigms on several issues, but rarely articulate dissent from the basic worldview that states are here to stay, both factually and normatively. Thus far, the postcolonial thinkers have been the most explicit about their not sharing in the ‘interstate’ vision of realists and liberals.

6Since its beginnings around the First World War, and until approximately 1990, international relations evolved as a controversy between liberal and realist perspectives, that is, the state system seen as ‘bellum omnium contra omnes’ and the same seen as a ‘global community’. Surprisingly, it was not the vision of a Hobbesian jungle advocated by cynical practitioners and the belief in cooperation promoted by star-gazing professors. Liberals Wilson and Angell were both practicing politicians; realists Morgenthau and Waltz lived their lives mostly within academia.

Though later the social roles of the paradigm promoters became less differentiated, Morgenthau’s and Waltz’s status as professors has left a deep impact on realism. First, and most obviously, they articulated some severe norms of methodological rigor, which contributed to realism’s seeming to be a coherent paradigm, built on three clear-cut axioms, as compared to the ramifying, messy liberalism, first axiomatized by

Moravcsik (

1997), but not to the contentment of all liberals. Second, less obviously, but with very serious consequences, Morgenthau made efforts to slice out the domain of IR from the dense texture of global reality, and came up with a definition of its object that later has tacitly been accepted by all realists and affected their opponents in disputes, as well. IR, in his view, is the study of international politics as a struggle for power, and excludes, programmatically and categorically, concerns with “extradition treaties, commerce, providing relief from natural catastrophes, and cultural exchange”. This definition confines IR to the study of inter-state relations, rather than of inter-national relations. Nations, as groups of people, are interested in economic relations, culture, and keeping their environments free from pollution and crime. The assumption that their interest in political power allocations trumps or should trump all other interests is in need of supportive arguments. Realism does not fail to provide one, by paraphrasing Hobbes: the weak live dangerous and short lives. Yet realism’s actors to ‘live or die’ are simply the states as institutions, vacated of inherent attributes that would confer value on their maintenance. They are not groups of people, because people are always more interested in butter than in guns; they are not

demoi, because their strict control by a realistically thinking elite is highly desirable; they are not ethnicities, because their cultural survival does not substitute for the loss of statehood; and empirically, they are very far from the current real-world countries whose population includes, on average, 34% of minority ethnicities, and substantial masses of people who are, legally and/or historically, transnationals.

In the 1990s, the emerging (state)constructivist paradigm highlighted that IR’s two central concepts, state and the inter-state anarchy (the constellation defined by power struggle) are mutually constitutive notions. The constructivists used this argument to point out that the world is not necessarily a Hobbesian anarchy, but that it may be a Lockean and even a Kantian anarchy (

Wendt 1999). However, the epistemological conclusion to be drawn from this is that a theory with two axioms (as structural realism becomes when two of its three axioms are collapsed into one), has little to no explanatory or predictive power in the real world, and bringing in more empirical content is an epistemological must.

IR liberalism’s strongest argument in its dispute with realism has always been its going beyond the conceptualization of the state as a unitary actor in a struggle-for-power game, solely concerned with survival in a Hobbesian world. Yet mainstream IR liberalism backed away from taking a decisive step to break free from the conceptual frames imposed by its opponent. It resisted the conclusion that human interests should be prioritized above state interests. Most international institutions, even their most cherished IR liberal achievement, the United Nations system, are based on the principle of state sovereignty. State sovereignty is encoded in the UN charter while the Declaration of Human Rights comes as a voluntary undertaking of the states.

IR’s heavy reliance on enshrining state sovereignty was emphatically pointed out by

Walker (

1992). He also signaled the ethically problematic consequences of sovereignty, such as the legitimacy to resort to war, versus the illegitimacy of humanitarian intervention. Yet he derived the dominance of sovereignty-ensnared discourse from the stubbornness of an ‘exceptionally dense political practice’, while we think that there are some ideological causes to be factored in, as well. It was IR as an actual academic discipline that has failed to rid itself of the idolatry of sovereignty, even if there have been thinkers who did not buy into this creed.

First, there have been pacifists who tried to stop wars and limit states’ rights to wage wars. Closest to IR’s development, the names of Kant, Wilson, and Angell may come to mind, but we should also not forget the resistance to states and state-waged wars that religions have at times offered.

Second, a group of theorists after the Second World War worked out blueprints for peacefully unifying Europe, to the benefit of its peoples, but to the detriment of state sovereignties.

Praxis has yielded to the efforts of both: we have the UN system, various disarmament agreements, declining occurrence of inter-state war, and the European Union. IR, at least its realist version, has not yielded: for several still active scholars, the UN and the EU exist only as façades of the states’ power relations.

It seems that the impact of political practice on IR standpoints has been mediated by a cultural context in which war was accounted for as a ‘duel’, a sense that embodies the worldview of the Borgias and of

‘l’état c’est moi’. IR, as an actual discipline in the 20th century, searched for definitions and explanations of war in the writings of Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and Bismarck, rather than in the work of Gandhi, for instance; and remained unfazed by the UN’s voiding the term and replacing it with

aggression,

self-defense, and

humanitarian intervention7. Fortunately recently some criticism of the temporal or a-historical bias of IR has been added to the ongoing critiques of the Western bias.

McIntosh’s (

2015) sub-title ‘the privileging of time-less theory in international relations’ says it all.

Winter (

2011) sheds light on the attempt of some U.S. legal scholars, such as Michael H. Posner, to morally sanction ‘traditional’ wars, while throwing excessive blame on guerrilla movements and liberation struggles which involve ‘civilian spaces’.

Fixation with sovereignty goes hand in hand with fixation with war because of a second loop of mutually constitutive meanings: a state devoid of its internal functions and of concerns with, for example, “extradition treaties, commerce, providing relief”, is reduced to the sole attribute of making war, and war is something that is done by states as unitary actors solely motivated by their own survival. When states are motivated by the correctly perceived well-being of their populace, they avoid aggression and cooperate towards mutual benefits. This is the optimistic creed the IR liberals summed up in the democratic peace proposal, as promoted, for instance, by

Doyle (

1983),

Russett and Oneal (

2001). Yet IR resisted innovations both to its vocabulary, such as replacing ‘war’ with ‘aggression’, and to its basic worldview, such as of a humanity not compartmentalized into like-units called states. IR liberals aimed at replacing Hobbesian anarchy with inter-state law and institutions, but all did not endorse the agenda of changing the building blocks of the edifice, for instance, allowing for regional integrations maturing into new polities. Liberal intergovernmentalists, such as

Moravcsik (

1991), denied the possibility of this development while liberal international political economy theorists did not find it desirable. 20th century economic liberalism—the neoliberal, or orthodox, or Washington Consensus doctrine—stood for unrestricted world-wide free trade among self-contained and responsible (that is, financially accountable) units. From this perspective, OPEC sounded like a trade union, and the EU as the American Association of University Women. By staying with the realist fiction of a globe made up by ‘like unit’ states, liberals could spare the duty of addressing power structures apart from the military-political; and statist constructivism also tends to share in this fiction.

Other perspectives, the ‘newcomer’ ones, are concerned with power structures different from the inter-state relations. Feminism with the gender hierarchy, Marxism with the economic hierarchy, and versions of post-colonial thinking with either the economic hierarchy (as in dependency theorists) or the cultural dominance (as in Negritude studies, (

Spivak 1988), Bhabha). Postmodern theorists are less specific about their most hated power structure, but they obviously believe in the existence of more than inter-state anarchy alone. The point to be made is that there are inter-state events and developments that cannot be explained without factoring in more than state interests and inter-state power relations. For instance, Cold War behavior, certain voting patterns in the UN, and international terrorism challenge the worldview relying on states as ultimate explanatory principle.

The other concern strangely missing from IR is consideration of intra-state domestic heterogeneity. Its paradigms are predominantly silent about how to manage intra-state diversity, and definitely do not advocate its legitimacy and long-term survival. The unpopular conclusion of realism is that assimilation is desirable, and the unsupported hypothesis of liberalism is that sub-national communal affiliations are on their way to vanishing.

2.2.2. Challenges to the State/Anarchy Model: Sub-National Groups, Supranationality, Alternate Power Structures

The simplifying model of like-unit states, thrown into either Hobbesian or Kantian anarchy, makes so bold abstractions from the real-world complexities surrounding statehood that only very convincing empirical track records could justify the assumption. Unfortunately, the empirical predictive power of IR, and mainly of its realist perspective

8, does not support the value of dropping from analyses so many effects interfering with the military-political power structure. The postcolonial critique of the state system model emphasizes the Western biases of the concept of nation-state

9, and brings in a different vision of the state system, as well. In general, paradigms concerned with power structures above or beyond the military-political, expect alliances along the dominant-dominated fault line, and these ostensibly do occur. For instance, there are undeniable tensions between the developed and developing countries’ standpoints on the Palestinian issue, the assessment of U.S. interventions in the Arab world, and the economic policies pushed forward by the IMF and World Bank.

Nationalism is an important ingredient in the vision of a world composed of self-contained and accountable units. It is the link connecting individual and country-level events and also explaining why well-being-oriented individuals would subordinate their lives to the maintenance of a state. As for the details, realists claim that this self-sacrificing behavior may and should be imposed on citizens while liberals just assume that people’s ultimate collective identity is their national allegiance.

Empirically, though, 21st-century nationalism in the globe’s roughly 200 countries is not the same reality as the nationalism of the European countries in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Since the 18th century and up to the Second World War, Europe pursued the creation of ‘homelands’ in which the ethnies were congruent with the state boundaries, and forced assimilation of minority ethnies was largely tolerated. The new white immigrant countries (U.S., Australia, Canada) also practiced assimilationist policies, but under the aegis of a civic, rather than an ethnic, type of nationalism. After WWII, two new trends emerged:

- -

Experiences with multiculturalism, which allow sub-national groups to define and maintain a communal identity different from the country’s majority community identity—as in Canada and India;

- -

Experiences with supranationalism, which brings nations closer to each other by working on a superposed higher socio-territorial identity—as in the European Union.

Empirical studies revealed some consequential changes of the individual psyches, such as a general weakening of state-level nationalism as compared to other layers of socio-territorial identities

10; and the weakening of nationalism as compared to other social identities like political and professional (

Inglehart and Welzel 2005). Popular moods in Europe have become decidedly pacifist, and in conditions of consolidated democracy, this change has been causally consequential for the probability of war.

In fact, there have been several historical events that evidenced that people think and act in ways unexpected by IR realism, and sometimes, unexpected by IR liberalism, as well. The list of human actions that do not share in IR’s molds of state-rational behavior, but turned out to be highly consequential in the real world includes: passive resistance, guerrilla movements (both positive and negative, with either liberation or ‘drug wars’ and state failure as a consequence), maturing regional integrations, obeying international contracts and law, transnationalism (like workforce migration and terrorism), and ravaging civil wars. Some of these have taken by surprise well-intentioned liberals, as well, who could not see any complication in helping the opposition of some autocratic rulers to oust them from power, and found themselves in the midst of bloody communal wars such as in Syria and Ukraine. In general, the very palpable, large-scale consequences of political action initiated and carried out by entities other than sovereign states have ostensibly resulted in re-shaping the state system through secession, liberation, state failure, and pooling sovereignty.

Yet the explanation that IR’s state system yields to bottom-to-top effects, thus it can be shaped by individuals, is not theoretically appealing. Individuals’ idiosyncratic wants are unlikely to be the prime movers in the political universe. Non-random, thus cumulative and socially consequential human behavior, is a social fact, which, as Durkheim maintained, needs a social fact to explain. The nation-state system, as postulated by IR theorists, does not contain any developmental trend or dynamics of its own. It is static and timeless by default. If there is change in the state system, its source is to be retrieved either on a lower level

11 or as a power structure above and beyond the military-political structure. There are a few candidates for this latter role, primarily the global economy, which has a differential impact on wealthy and poor states, and weakens the competences of all of them. Religions have been pinpointed as pitting groups of countries against each other (

Huntington 1998) and as fueling international terrorism. Ideologies had their moment of fame during the Cold War, and since the 1980s, there has been a thriving literature dedicated to environmental movements.

We may wonder which of these alternate power structures is really strong enough to score a significant effect in accounts of global evolution. Unfortunately for the analysis, none of them is fully independent of the military hierarchy, and complicated interactions may emerge among the alternate power structures, as well. For instance, Islamic terrorism is likely to be motivated by the Islamic states’ economic disadvantage as compared to developed states with other dominant religions. Strong ethnic secessionist movements typically occur in the case of regions wealthier (Catalonia, Lombardy) or poorer (South Sudan) than the rest of the country. Here lies the U.S.’s striking departure from a series of values endorsed by most of the international community, routinely explained by IR with ‘conflicting state interests’. For instance, the U.S. did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol, left the Paris agreement, and opposed the establishment of the International Criminal Court (see

Fehl 2012 for a longer list).

Betti (

2016) points out two important facts: (i) opinion polls show that a majority of Americans have supported these international solutions; (ii) typically, Democrats were willing to go with them while Republicans were vehemently opposing them. This suggests that Republican policy-makers managed to subdue both Democratic policy-makers and the wider public opinion in the domestic-level contest for defining the country’s national interest. Trump’s ‘make America great again’ tapped deeply and successfully in the investors’ drive to bust governments that are slow in opening their markets to U.S. businesses, or ask for concessions in exchange, like NAFTA partners. Overall, some economic special interests are being served by fueling the belief in American exceptionalism and bullying other countries (‘making Mexico pay for the wall’)—and we may wonder how to conceptualize this: as the impact of the domestic ideologies on inter-state anarchy, or the impact of the inter-state economics on domestic politics?

Sadly, the dense and complicated causal structure of the social world—e.g., multi-causality and proliferation of feedback-loops—resists the simple and elegant explanations so much prized in IR; and it seems that the preference for simple and elegant explanations is but an aspect of buttressing the core vision of like-unit states. That is, a number of further epistemological challenges faced by IR are related to its promotion of the inter-state vision.

2.2.3. Some Related Epistemological Issues within IR

Level-of-analysis concerns have been at the core of IR’s epistemological awareness since its inceptions, but

Waltz’s (

1959) articulation of the issue made them a cornerstone topic of evaluation of scholarly performance in the domain. We concur with Waltz’s basic claim that higher-level systems constrain and shape the behavior of the components, and the behavior of the components cannot be fully explained without accounting for effects that from their perspective are environmental impacts. As already mentioned, one issue with this vision is that the country’s environment cannot be reduced to a military power structure since it is much richer in power hierarchies.

But there are other issues with the three-level vision of Waltz. The causal primacy of a system above its components does not mean either causal exclusivity or existential and chronological primacy. Most of the time we have a co-evolving relationship between the whole and the part, which justifies the search for part-to-whole influences, and actually, makes it necessary. As a further illustration of the mutual constitutiveness of state and anarchy, the like-unit conception of states makes the causal exclusivity of the system versus components a more plausible narrative. Yet in virtue of this narrative, a useful tool in the researchers’ toolbox,

Nagel’s (

1961) ‘bridge laws’, were completely rejected by IR realists, and not well developed by liberals. Furthermore, the narrative also prohibited epistemic reflection on a second plague striking social sciences, besides complexity. In social science, the delimitation of the analysis levels is much more arbitrary than in natural sciences. Social disciplines and sub-disciplines constitute their levels of interest in various ways. Social psychology in the Tajfel tradition sees individuals and groups; sociology in the Weberian tradition sees individuals and institutions; Marxian sociology sees individuals, classes, and modes of production, while the Durkheimian version of sociology tries to eliminate individuals as explanatory principles at all. Political science, and most specifically its IR domain, focuses on the state and defines other levels in function of this, but as a difference from other social disciplines, it makes the claim that this delimitation of the levels of analysis deserves an exceptional status among alternate conceptualizations of the social world. Mainstream IR, as fashioned in the U.S. in the second half of the past century, promotes the belief that foreign affairs do, or should determine domestic affairs, with the most obvious implication that militarization becomes an imperative.

Sifting through the epistemological and methodological claims most authoritatively promoted within IR, we may be surprised by the dearth of concerns with adequacy, accuracy, precision, and practical value. Most typically,

Waltz (

1979) stated that theories should be logical, coherent, and plausible (Chapter 1) and further, possessing explanatory power, predictive power, and elegance, which means that “explanations and predictions will be general” (Chapter 4). This is congenial with

Olson’s (

1982) epistemological ideals, celebrating power (when a large number of phenomena are explained), persuasiveness, and parsimony. Theorists working in the rational choice tradition definitely have a tendency to revere generality and simplicity to the detriment of empirical content and practicality, and besides economics, IR is the domain in which RCT has achieved the most dominant position

12. Coherence and generality (or scope, or power) of explanations are really justifiable ideals. Yet parsimony does not stand scrutiny as a goal to pursue in science, and in many disciplines, it has categorically been dropped following mature epistemological reflection. In empirical sciences, generality does not actualize as a small number of axioms underlying all manifestations of a reality domain. Instead, generality actualizes as completeness, as a grand theory composed of sub-fields addressing different levels, aspects, and domains of the phenomena studied. Think about the Bohr model of the atom: it was logical, coherent, plausible, and parsimonious. Yet contemporary science constructs atoms out of quarks, leptons, and bosons, let alone further divisions into up and down quark, gluon, photon, and neutrino.

RCT, or formal modelling in IR, is mostly domain-specific, tied to concerns about anarchy, but by the nature of the paradigmatic divisions in the field, it has mainly been promoted by realists. Liberals’ most typical empirical endeavors were centered on the ‘epidemiologic’ methodology with which they hoped to reveal the causes of wars. This method is better synchronized with what other empirical sciences discovered to be useful, but contentment with probabilistic techniques involves a compromise with imprecision. As applied in IR, probabilistic modelling promotes the much-needed ideal of testability, yet it remains prey to an unjustified craving for generalization. For instance, all wars are believed to have the same causes, independently of their historic era, regional location, a disparity between the belligerents, and a number of other features.

Constructivism, institutionalism, and postmodernism articulated their opposition to the pre-existing IR corpus from methodological standpoints. In Marxism and feminism, the alternate existential claims are also very emphatic. Today we cannot help imagining IR as a methodologically pluralist discipline, and yet the long realist-liberal dominance of the field has left some very persistent legacies. For decades, parties in the methodological disputes defined and defended their position in function of levels or “images” (

Gourevitch 1978;

Grieco 1988). Even the newest generations of IR students are trained to think in terms of the three analysis levels and focus their research on one of them. Emergence and reduction, bridge laws, intermediate levels and alternate power structures are not part of the standard epistemological discourse in IR.

3. Discussion: Beyond Four Disciplines, beyond Nationalism, or beyond the North–South Divide?

The foregoing analyses were geared towards showing that international relations, as we know it, is quite vulnerable to both axiological and epistemological criticisms. Three of the often criticized axiology issues are: enshrining state sovereignty (de facto, even if not in principle, to the detriment of human rights and towards legitimization of war); promoting the Western-envisioned nation-state versus multicultural states, tribal societies and regional integrations; and neglect of the necessity of ecological cooperation. A newly strengthening critical concern highlights IR’s difficulty to conceptualize global poverty as a predicament to be dealt with (

Blunt 2015). All these are neatly aligned with the American core of IR. The creed in like-unit individual states having equal opportunities to flourish when thrown in a competitive marketplace echoes the beliefs in the Protestant work ethic and the Invisible Hand, which made the U.S. the only developed country where life expectancy and the middle class have been shrinking since the Reagan era. In fact, there is a striking similarity between IR’s claim that states’ pursuit of survival is beyond ethical judgment, and neoliberal economics’ idolatry of businesses, which allows corporations to disregard humanitarian considerations in pursuit of thicker bottom lines, if not tacitly encouraging unethical behavior in the pursuit of the same goal.

Finally, the vindication of a special status for IR among other social sciences, as originated by IR realism, is also heavily biased. It supports practices such as lack of transparency regarding military expenses, including, for instance, the neglect of auditing the Pentagon.

Axiological biases are not exogenous to research: they tend to direct and confine analyses and marginalize divergent interest and opinions, often in quite imperceptible ways.

We made the statement that methodological nationalism is related to political nationalism; yet we do not claim that all researchers working within the fields of IR, IS, AS, and GS, who show some degree of methodological nationalism, are political nationalists themselves. We tried to survey the epistemological contexts within which methodological nationalism transmits and may affect even people with a sincere aspiration towards global inclusiveness. Methodological nationalism became deeply entrenched in IR, which is also penetrated by political nationalism, and which has constituted itself in ways that glorify both political and methodological nationalism. IR has had a major role in the evolution of IS and AS, yet in these disciplines (plus in GS) we may witness more tolerance towards methodological pluralism and less effort towards synchronizing basic worldview and basic methodology. Scholars in the field of IS and AS are, by the logic of the facts, much more diverse than IR’s classics; and both disciplines were born as empirical research fields, which allowed for some methodological independence from their IR midwife. Even more methodological independence can be attributed to the programmatic interdisciplinarity of these disciplines. Mainly sociology may be credited with bringing in worldviews not dominated by nation-states, and a methodological consciousness superior to that of IR.

As discussed in the first section of the paper, the Global Studies Association, and some basic publications in the field of global studies, are dominated by sociologists fascinated by globalization and global networks. Sociology managed to go beyond the imagery of nation-states much before the birth of the GSA. None of the Founding Fathers of sociology (Marx, Weber, Durkheim) thought of nation-states as either historically long-term frames of human existence or a sensible tool for analysis. Today’s sociologists are vocal supporters of transcending state-centered ways of thinking, as well as Westernist biases, yet the calls for theory-building are less intense than in the 19th century, for instance. The field including global studies is badly in need of theories that hammer out notions of global structures, and posit causal directions in-between and within them. Thus far only one stream of sociological scholarship came close to be acknowledged as part of IR, the world systems theory, and its presence remained confined to the international political economy subfield of IR.

World systems theory is a paradigm that radically collides with the nation-state/anarchy model in several respects: it postulates alternate power structures (the economic), it reveals a basic fracture within nation-states (the class issue), and is critical of the whole value structure promoted by IR (such as sovereignty, the right to war, the business model of human affairs). It is a version of global thinking, but it is not routinely incorporated into global studies, at least not in the U.S.

As a counterpoint, Chumakov heavily relies on the Marxist historiography underlying the world systems theory. He constructs globalization as an aspect of the emergence of capitalism and its expansion around the globe. ‘Globalization

13 is a necessary result of the historical process and an essential feature of social development from the moment of the emergence of capitalist relations’ (

Chumakov 2010, p. 36). Furthermore, Chumakov’s description of increasing awareness about globalization includes Marx and Engels as the first thinkers to point out the impending political and economic closing of the world. Chumakov has introduced the powerful notion of ‘closing’ (or ‘closed-ness’)—in fact, this taps on the essence of globalization, the dense interconnectedness, when events in one part of the world affect events in other parts of it. He also set up a chronology of reaching closed-ness in different domains, in a sequence of political, economic, ecological, informational, and impending civilizational.

Yet there is some issue with identifying globalization as a capitalist epiphenomenon, logically speaking, there is an ‘after this, therefore because of this’ challenge here. Humanity inhabiting the planet has always been destined to ‘grow together’, that is, the ecological and epidemiologic closing was built into the fate of the species. From this perspective, it is accidental that the political and economic closing was reached when the West attained the capitalist phase. Had the globe been smaller, this could have happened under Alexander the Great or under Charlemagne, and then we would have had a slaveholder or a feudal globalization. Thus, while the capitalist economy’s expansive dynamics were very correctly described by Marx and Engels, the previous social formations also had strong expansive tendencies built in, which failed to engulf the globe because of a combination of population density and technical might.

Looked at from this perspective, globalization is an ‘actually existing globalization’, a quasi-contingent outcome of the planet’s size and humanity’s speed of evolution. This ‘actual globalization’ incorporates striking capitalist features along with characteristics that express a deeper interconnectedness than dictated by the capitalist world economy and its most comfortable political mold. For instance, the ecological, epidemiological, and informational interconnectedness seem to go beyond or beneath the capitalist economy and the U.S. dominated state system. Recognizing this duality inherent in globalization is as important to theorists as to ‘anti-globalization’ activists. As for the latter, the duality indicates that only ‘anti-capitalist-globalization’ or ‘alter-globalization’ movements (or “universalist protectionist” movements, using the term of

Steger 2007) have reasonable chances of success; and these obviously rely on informational globalization and use ecological and epidemiological globalist arguments. As for the theory, we may wonder whether it was time for the U.S. version of global studies to come up with some pillars that codify a truly global outlook into globalization. For instance,

Babones (

2007) would prescribe the involvement of a global level of analysis. We would suggest an analytical framework that highlights which features of our global interconnectedness are shaped by unbridled capitalism and which are here to stay even in conditions of

Polanyi’s (

1944) ‘embedded markets’. It should also involve a study of the role or function of nation-states, and whether our world is doomed to be ‘inter-state’, rather than ‘global’. As of today, the informational closing of the world makes possible that non-Western views on globalization are heard, such as dependency theory, world-systems theory, Pope Francis’ Catholicism, and postcolonialist thinking in several disciplines; yet none of these managed to make a serious impact on current globalization, which keeps working along a neoliberal economic logic. The way of ideologies to influence economy runs through the state, and here the anti-actual-globalization ideals are caught in a catch 22. What are the chances of the citizenry of a small and weak state to push through a global Tobin tax, for instance? The most reasonable scenario for a citizenry preponderantly committed to combatting poverty is to establish redistributive policies within the state and protect the national economy by setting limits on foreign trade and investments—that is, through strengthening the nation-state. Since lately the wealthiest nation on the earth has also played this protectionist-nationalist card (yet against redistribution), we have to conclude that gatekeeper conservatism and action-oriented opposition to it are both likely to rely on nation-states in their pursuits and keep referring to beyond-the-border concerns as ‘globaloney’.

In fact, within the U.S., global studies have eked out a narrow plot for themselves mostly in small private liberal arts colleges, which are usually taken for fostering l’art pour l’art hermeneutic preoccupations. By 2017, only 37 public institutions managed to channel tax money in research expressly called global studies, out of the approximately 700 public 4 year colleges and universities. Actually, the statistics do not look better in any country: Russia, Japan, the UK, and Australia all seem to have only one academic center dedicated to global studies. While the researchers have grown increasingly fascinated with globalization over the last three decades, governments have shown little interest in supporting this type of inquiry. There are government advisors on immigration, foreign trade, and foreign affairs—but not on ‘global policies’, and not even on ‘globalization policies’ (and the advisors on immigration, foreign trade, and foreign affairs are unlikely to have other vision than IR’s inter-state worldview).

The U.S. institutions that run global studies programs try to brand them as a useful major with good job prospects, but these latter are practically identical with the job prospects for the international studies, both further overlapping with those of area studies and international relations. Both from the perspective of institutional history and labor market shares, the four areas look like subfields of the same discipline, rather than distinct social fields. Currently, in the U.S. and in most of English language scholarship, IR is the ‘theory-generating’ area, while the other three exist as empirical studies. The major challenge to global studies is to become a theory generating field at parity with, and hopefully overcoming, IR’s established paradigms. For instance, it could offer a coherent view of global society that puts nation-states and nationalisms in their place, establish causal connections among meaningfully outlined components of the global system, and make predictions about the evolution of globalization. Humanity badly needs such a discipline, both for descriptive and normative purposes. For instance, the United Nations delegitimized wars by switching to a terminology that replaces ‘war’ with ‘aggression’, ‘self-defense’, and ‘humanitarian intervention’. Yet some scholars, mainly in the U.S., still find theoretical justifications for wars, including the hegemonic ‘pre-emptive’ wars.

The challenges to unifying the four areas under a powerful global-outlook theory (or even under several competing global-outlook paradigms) are not trivial. Within the academic world, the inertia of the entrenched institutions and the resistance of methodological nationalism are overwhelming on their own. Yet the larger social context within which the academic venture unfolds also favors the maintenance or frequent recurrence of political nationalism in several countries and for various reasons. In the developed world, right-wing populist nationalism has become a successful electoral platform over recent decades. In the developing countries, anti-capitalist/anti-Western nationalism is more frequent, though more variegated, ranging, for instance, from the Muslim Brotherhood through some East European autocracies to the Latin-American experiments with socialism (which are, otherwise, highly supportive of the World Social Forum-type alter-globalization). The leading theme of right-wing populist nationalism is anti-immigrationism, that is, it protects the Westerners’ privileges against individual challengers to it, but nationalist extremists are more and more open about their willingness to use force to impose certain economic rapports on other countries. On the developing side, economic arguments are often mixed with cultural ones, but there is a considerable consensus among all types of underdeveloped-country nationalisms, that unbridled global markets only benefit the giant transnational companies whose profits go to their first-world owners. The north–south divide seems to beget nationalisms day by day, and the widening gap exacerbates this effect. The relationship between inequality and proneness to extremism, including right-wing extremism with its usual nationalist and racist overtones, has already been studied, but it is time to take the studies to the next level by factoring in the impact of global inequality, as well.

Finally, it is difficult to imagine a global theory without an emphatic economic component. The study of globalization started with economic aspects; and even IR, which places the nation-state in the center of the socio-political universe, has developed a political economy branch. When starting from the perspective of culture, the single most important cultural shock of the 21st century is the unfolding of ‘casino capitalism’. Furthermore, the field of economic thinking is as polarized as that of the politics beyond the nation-state. There is, on the one hand, neoliberal economics so warmly welcoming economic globalization but without any propensity to move beyond the idea of a globe segmented in nation-states, as stable states are the utmost guarantee of collecting debts from impoverished debtors. There exists, on the other hand, the world systems theory of Wallerstein, with its Marxist origins and deep similarities with the Latin-American dependency theories. These are exactly the same poles we see in domestic politics, as well. Why not think about the globe as one complex society where boundaries are contingent and fluid, and states are Janus-faced institutions exploitable both as well-intended regulators to make life more humane and as fortresses defending the privileges of some fortunate human groups?