Effects of Gay-Themed Advertising among Young Heterosexual Adults from U.S. and South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Attitude toward Homosexuality in the United States and South Korea

2.2. Effects of Gay-Themed Ads in United States and South Korea

2.3. Cultural Orientation (Individualism vs. Collectivism) and Its Effects in Tolerance toward Homosexuality, Gay-Themed Ads, and the Brand

2.4. Effects of Gender in Tolerance toward Homosexuality, Gay-Themed Ads, and the Brand

2.5. Types of Gay-themed Ads: Homosexual Male Imagery Print Ads vs. Lesbian Imagery Print Ads

3. Method

3.1. Subjects, Designs, and Procedure

3.2. Experimental Stimuli and Pre-Test

3.3. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Cultural Orientation: Individualism vs. Collectivism

4.2. Effect of Gender in Tolerance toward Homosexuality, Attitude toward Ad, and Brand

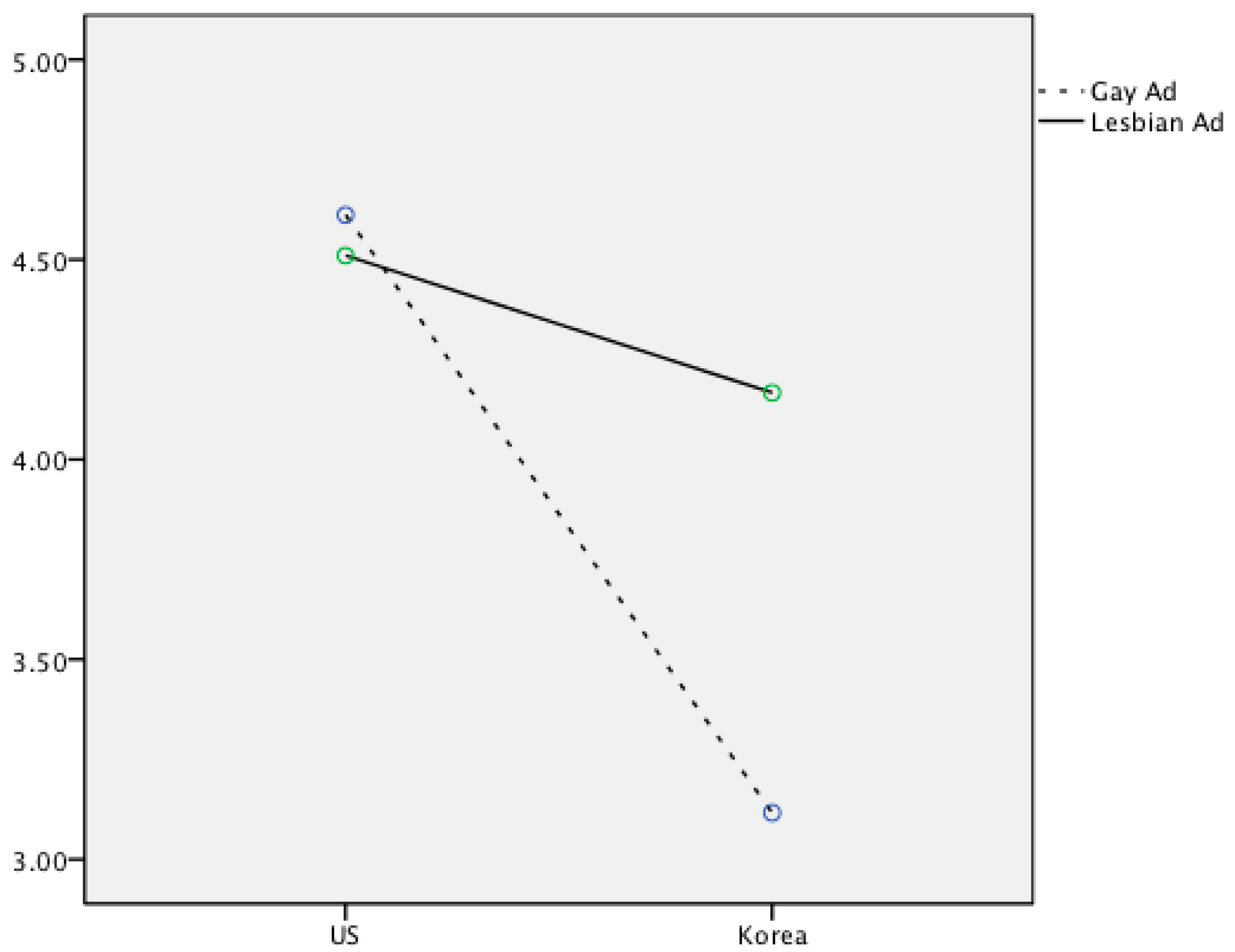

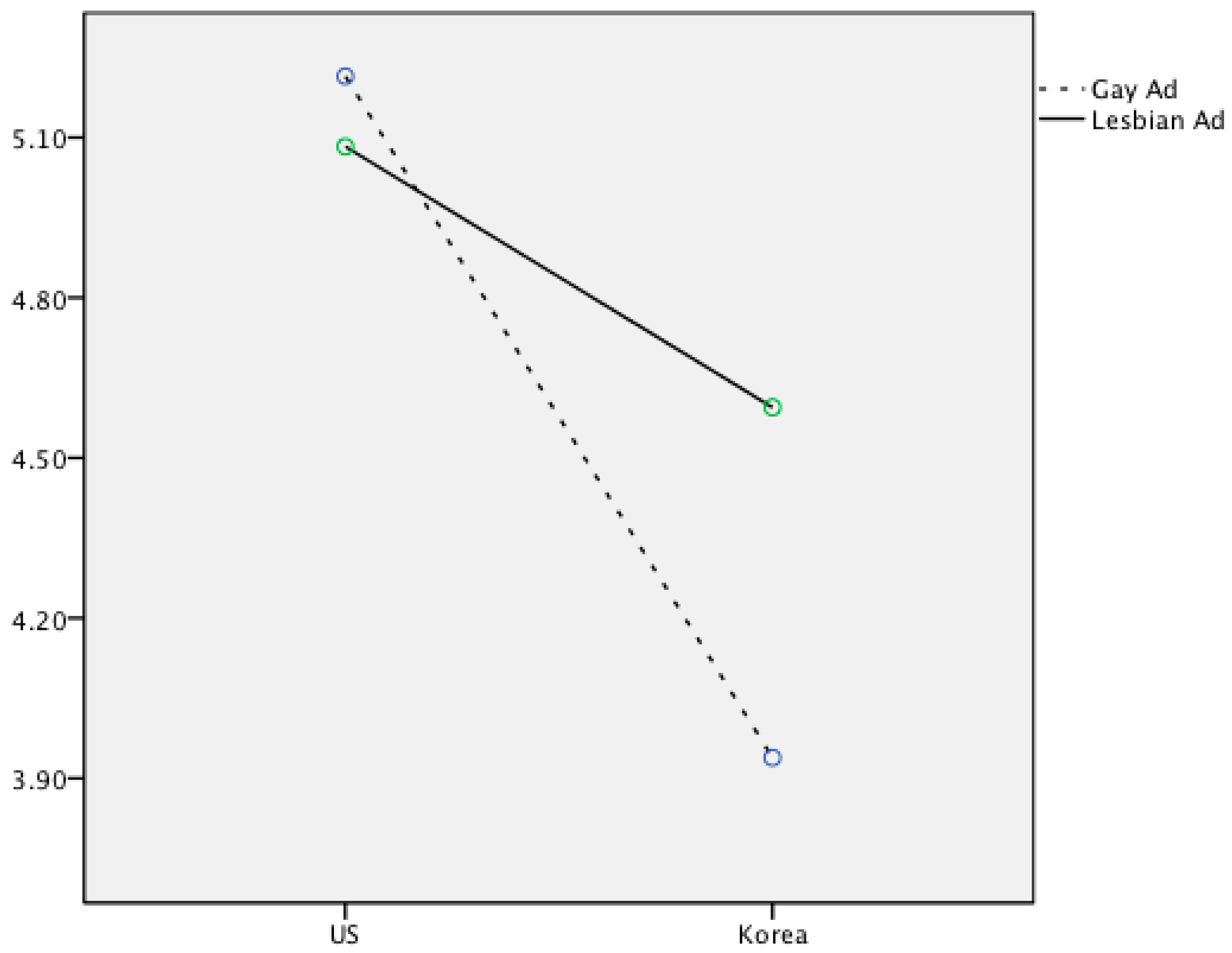

4.3. Types of Gay-Themed Ads: Gay Male Imagery Print Ads vs. Lesbian Female Imagery Print Ads

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Areas for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adolfsen, Anna, Saskia Keuzenkamp, and Lisette Kuyper. 2006. Opinieonderzoek onder de bevolking. Gewoon doen. Acceptatie van Homoseksualiteit in Nederland. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, pp. 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Angelini, James, and Samuel Bradley. 2010. Homosexual imagery in print advertisements: Attended, remembered, but disliked. Journal of Homosexuality 57: 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, Subodh, Thomas Leigh, and Danniel Wardlow. 1998. The effect of consumer prejudices on ad processing: Heterosexual consumers’ responses to homosexual imagery in ads. Journal of Advertising 28: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonauto, Marry, and Jeffrey Robbins. 2013. Rising Hostility against LGBT Americans Belie Gains. Boston Globe. Available online: http://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2013/01/15/podium-lgbt/RWUuvnDT4Ldvjodf0HNFAP/story.html (accessed on 9 September 2013).

- Chebat, Jean-Charles, Mathieu Charlebois, and Claire Gélinas-Chebat. 2001. What makes open vs. closed conclusion advertisements more persuasive? The moderating role of prior knowledge and involvement. Journal of Business Research 53: 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinman, Saul. 1981. Why is cross-sex-role behavior more approved for girls than for boys? A status characteristic approach. Sex Roles 7: 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Leigh E. 2011. Minimizing heterosexism and homophobia: Constructing meaning of out campus LGB life. Journal of Homosexuality 58: 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallup Korea. 2013. South Korea Easing Homophobic Views on News of Gay ‘Wedding’. Available online: http://www.news.com.au/world/south-korea-easing-homophobic-views-on-news-of-gay-wedding/story-fndir2ev-1226655223769 (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Herek, Gregory M. 1984. Attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A factor-analytic study. Journal of Homosexuality 10: 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herek, Gregory M. 1988. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research 25: 451–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1980. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, Harry. 1988. Measurement of individualism-collectivism. Journal of Research in Personality 22: 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsos. 2013. Same Sex Marriage. Available online: http://www.ipsos-na.com/download/pr.aspx?id=12795 (accessed on 5 June 2015).

- Italie, Leanne. 2013. Gay-Themed Ads Are Becoming More Mainstream. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/06/gay-themed-ads-mainstream-_n_2821745.html (accessed on 20 January 2015).

- Kardes, Frank. 1988. Spontaneous inference processes in advertising: The effects of conclusion omission and involvement on persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 225–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleher, Alison, and Eric Ran Smith. 2012. Growing support for gay and lesbian equality since 1990. Journal of Homosexuality 59: 1307–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, John G., and Mark A. Fine. 1994. The relation between gender and negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: Do gender role attitudes mediate this relation? Sex Roles 31: 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Heejung, and Hazel Markus. 1999. Uniqueness or Deviance, Conformity or Harmony: A Cultural Analysis. Unpublished manuscript. Stanford, CA, USA: Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Kite, Mary, and Bernard Whitley. 1996. Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights: A Meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22: 336–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMar, Lisa, and Mary Kite. 1998. Sex differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: A multidimensional perspective. Journal of Sex Research 35: 189–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptak, Adam. 2015. Supreme Court Ruling Makes Same-Sex Marriage a Right Nationwide. New York Times. June 26. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/27/us/supreme-court-same-sex-marriage.html (accessed on 23 September 2015).

- Louderback, Laura, and Bernard Whitley. 1997. Perceived erotic value of homosexuality and sex-role attitudes as mediators of sex differences in heterosexual college students’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Journal of Sex Research 34: 175–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyi, Daeryong, and Jonghwan Kim. 2000. A study on the attitude toward advertisements using homosexuality. Journal of PR and Advertising Research 7: 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lyi, Daeryong, and Chan Park. 1999. Gay and lesbian consumers: A coming-out paper. Journal of PR and Advertising Research 7: 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, Scott, and Richard Lutz. 1989. An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing 53: 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Hazel. 1977. Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 35: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Hazel, and Shinobu Kitayama. 1991. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review 98: 224–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakenfull, Gillian, and Timothy Greenlee. 1999. All the colors of the rainbow: The relationship between gay identity and response to advertising content. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Society for Consumer Psychology, San Antonio, TX, USA, February 22. [Google Scholar]

- Oakenfull, Gillian, and Timothy Greenlee. 2004. The three rules of crossing over from gay media to mainstream media advertising: Lesbians, lesbians, lesbians. Journal of Business Research 57: 1276–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakenfull, Gillian, and Timothy Greenlee. 2005. Queer eye for a gay guy: Using market-specific symbols in advertising to attract gay consumers without alienating the mainstream. Psychology & Marketing 22: 421–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2015. 5 Facts about Same-Sex Marriage. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/27/same-sex-marriage (accessed on 27 April 2015).

- Power, John. 2012. Can Korea Ever Accept Homosexuals. The Korea Herald. June 18. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20120618000725 (accessed on 5 April 2015).

- Rivendell Media. 2014. 2014 Gay Press Report. Available online: http://rivendellmedia.com/documents/GayPressReport2014.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2015).

- Sawyer, Alan, and Daniel Howard. 1991. Effects of omitting conclusions in advertisements to involved and uninvolved Audiences. Journal of Marketing Research 28: 467–74. [Google Scholar]

- Spears, Nancy, and Surendra Singh. 2004. Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising 26: 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henry, and John Turner. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by Stephen Worchel and William G. Austin. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Paul. 2013. A Survey of LGBT Americans: Attitudes, Experiences and Values in Changing Times. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, Lefa, and Michel Laroche. 2006. Interactive effects of appeals, arguments, and competition across North American and Chinese cultures. Journal of International Marketing 14: 110–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, Harry. 1995. Individualism and Collectivism. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Wan-Hsu. 2004. Gay Advertising as Negotiations: Representations of Homosexual, Bisexual and Transgender People in Mainstream Commercials. In GCB—Gender and Consumer Behavior. Edited by L. Scott and C. Thompson. Madison: Association for Consumer Research, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tuten, Tracy. 2005. The effect of gay-friendly and non-gay-friendly cues on brand attitudes: A comparison of heterosexual and gay/lesbian reactions. Journal of Marketing Management 21: 441–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, Namhyun. 2014. Does gay-themed advertising haunt your brand? The impact of gay-themed advertising on young heterosexual consumers. International Journal of Advertising 33: 811–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, Michael. 2007. Gay Marketing Resources. Available online: http://www.commercialcloset.org/cgibin/iowa/about.html?pages1⁄4resources (accessed on 15 July 2015).

- Witeck Communications. 2016. American’s LGBT 2015 Buying Power Estimated at $917 Billion. Available online: https://rivendellmedia.com/assets/quicklinks/LGBT%20Buying%20Power%202016.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2018).

| Group (N = 330) | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individualists (n = 167) | Collectivists (n = 163) | |||

| Tolerance toward homosexuality | 5.74 (1.26) | 3.30 (1.63) | 183.35 | 0.000 |

| Effects | df | F | η2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Familiarity (Covariate) | 2, 319 | 5.19 | 0.032 | 0.006 |

| Brand Knowledge (Covariate) | 2, 319 | 5.49 | 0.033 | 0.005 |

| Cultural Orientation (A) | 2, 319 | 35.62 | 0.183 | 0.000 |

| Gender (B) | 2, 319 | 0.166 | 0.001 | 0.847 |

| Ad Type (Gay/Lesbian) (C) | 2, 319 | 3.93 | 0.024 | 0.021 |

| A × B | 2, 319 | 0.297 | 0.002 | 0.743 |

| A × C | 2, 319 | 7.63 | 0.046 | 0.001 |

| B × C | 2, 319 | 0.55 | 0.003 | 0.576 |

| A × B × C | 2, 319 | 1.66 | 0.01 | 0.193 |

| Dependent Variables | Source of Variation | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward ad | Cultural Orientation (A) | 1, 320 | 54.89 | 0.000 |

| Gender (B) | 1, 320 | 0.26 | 0.610 | |

| Ad Type (Gay/Lesbian) (C) | 1, 320 | 7.78 | 0.006 | |

| A × B | 1, 320 | 0.00 | 0.985 | |

| A × C | 1, 320 | 15.27 | 0.000 | |

| B × C | 1, 320 | 0.73 | 0.393 | |

| A × B × C | 1, 320 | 1.23 | 0.269 | |

| Attitude toward brand | Cultural Orientation (A) | 1, 320 | 59.65 | 0.000 |

| Gender (B) | 1, 320 | 0.00 | 0.924 | |

| Ad Type (Gay/Lesbian) (C) | 1, 320 | 2.28 | 0.132 | |

| A × B | 1, 320 | 0.36 | 0.547 | |

| A × C | 1, 320 | 6.32 | 0.012 | |

| B × C | 1, 320 | 1.01 | 0.315 | |

| A × B × C | 1, 320 | 3.32 | 0.069 |

| U.S. (Individualism) (N= 167) | Korea (Collectivism) (N = 163) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 65) | Female (n = 102) | Male (n = 67) | Female (n = 96) | |||||

| Gay Men Print Ad (n = 27) | Lesbian Print Ad (n = 38) | Gay Men Print Ad (n = 53) | Lesbian Print Ad (n = 49) | Gay Men Print Ad (n = 29) | Lesbian Print Ad (n = 38) | Gay Print Ad (n = 46) | Lesbian Print Ad (n = 50) | |

| Attitude toward ad | 4.46 | 4.55 | 4.74 | 4.37 | 3.08 | 3.93 | 3.11 | 3.99 |

| (1.92) | (1.09) | (1.17) | (1.08) | (1.29) | (0.72) | (1.16) | (1.06) | |

| Attitude toward brand | 5.13 | 5.17 | 5.34 | 4.9 | 3.95 | 4.33 | 3.87 | 4.3 |

| (1.19) | (0.91) | (0.82) | (0.90) | (1.19) | (0.77) | (1.41) | (1.04) | |

| Group (N = 330) | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n = 132) | Females (n = 198) | |||

| Tolerance toward homosexuality | 4.20 (2.04) | 4.76 (2.02) | 6.11 | 0.014 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Um, N.; Kim, D.H. Effects of Gay-Themed Advertising among Young Heterosexual Adults from U.S. and South Korea. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010017

Um N, Kim DH. Effects of Gay-Themed Advertising among Young Heterosexual Adults from U.S. and South Korea. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleUm, Namhyun, and Dong Hoo Kim. 2019. "Effects of Gay-Themed Advertising among Young Heterosexual Adults from U.S. and South Korea" Social Sciences 8, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010017

APA StyleUm, N., & Kim, D. H. (2019). Effects of Gay-Themed Advertising among Young Heterosexual Adults from U.S. and South Korea. Social Sciences, 8(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010017