Abstract

This paper utilizes the National Disaster Response Framework 2013 guidelines to analyze the large-scale disaster response of the Nepal government’s institutional system in the wake of the 2015 earthquake. The methodology includes in-depth interviews with key informants, focus group discussions, field observations, and document analysis. The study found that despite limitations in institutional capacity and scarcity of resources, government institutions such as the Nepal Army, the Nepal Police, the Armed Police Force, the District Administration Offices, the Ministry of Home Affairs, and major public hospitals made a significant contribution to support the victims. Nevertheless, it also revealed the current weaknesses of those institutions in terms of response effectiveness and provides recommendations for enhancing their capacity.

1. Introduction

Nepal is a mountainous country bordering India to the east, west, and south and China to the north. High mountain ranges, active tectonic processes, and heavy monsoon rain have made the physical environment vulnerable to natural hazards such as floods, landslides, windstorms, fires, earthquakes, and glacial lake outburst floods (GoN MoHA and DPNet-Nepal 2015; GoN 2017). Nepal ranks 4th and 11th worldwide in terms of its vulnerability to climate change and earthquakes, respectively. More than 80 percent of its total population is at risk of natural hazards (GoN 2017).

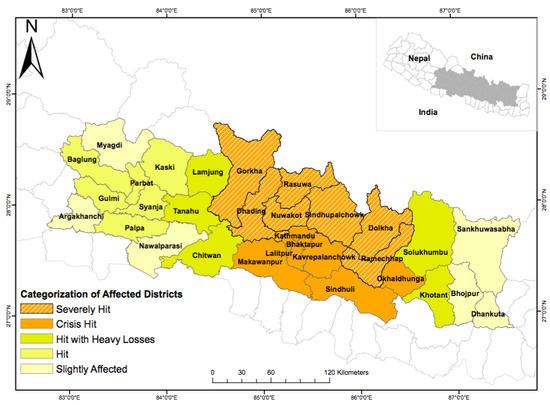

A 7.6 magnitude earthquake on Saturday, 25 April 2015 at 11:56 local time, struck the Barpak district of “Gorkha,” about 76 Km northwest of Kathmandu, Nepal (GoN NPC 2015). More than 300 aftershocks followed the first earthquake. One aftershock measuring 7.3 struck on 12 May which was the second biggest after the 25th of April. Officially over 8790 casualties and 22,300 injuries were reported. The lives of eight million people, nearly one-third of the population, were affected by the disaster. Out of 75 districts, 31 were affected and 14 were declared “severely hit” and “crisis-hit.” On the other hand, in terms of masonry building damage scale (Alexander 2015), severely hit refers to collapse, crisis-hit refers to very heavy damage, hit with heavy losses refers to heavy damage, hit refers to moderate damage, and slightly affected refers to slight damage. Figure 1 is a map of the affected districts and its prioritization for rescue and relief operation. The destruction included residential and government buildings, heritage sites, schools, health facilities, rural roads, bridges, water supply systems, agricultural land, trekking routes, hydropower plants, and sporting facilities (GoN NPC 2015). Rural areas in the central western regions faced a lot of devastation and further isolation due to the damage to roads, which made relief and rescue operations challenging. The total value of damage and loss caused by this earthquake was estimated to be USD 7 billion (GoN NPC 2015).

Figure 1.

Prioritization of affected districts (Source: GoN NPC (2015) PDNA Report).

Subsequent to the 25 April earthquake, the National Emergency Operation Center (NEOC) was activated at level four. The activation of the NEOC followed the guidelines of the National Disaster Response Framework 2013 and the standard operating procedures of the NEOC (GoN MoHA 2015). The NEOC SOP1 states that at level four, the decision is set by the Cabinet of Ministers. Thus, the Government of Nepal (GoN), through its Cabinet meeting on 25 April 2015 at 16:00. local time, made an official request for international assistance (GoN MoHA 2015, 2017).

Over recent decades, Nepal has been trapped in internal conflicts for peace and development. Political instability, lawlessness, clientelism, and lack of accountability and corruption are perceived to be a major concern (Von Einsiedel et al. 2012 as cited by Jones et al. 2014). In addition, disaster risk reduction policies and plans are constrained by factors such as a disparity of implementation capacity amongst line ministries and their departments at the national and subnational level (GoN MoHA and DPNet-Nepal 2013; Manandhar et al. 2017). In the absence of state expertise and capacity, international and national non-governmental organizations play a vital role in the implementation and coordination of disaster management in the country (Jones et al. 2014; GoN MoHA and DPNet-Nepal 2013, 2015). Rajan (2002) as cited by Jones et al. (2014), argues that while this support may be valuable in disaster risk management, it simultaneously poses a challenge for building national capacity and government ownership.

In Nepal, disaster risk management strategies do not seem to be accompanied by a thorough understanding of institutional capacity (strengths and weaknesses). The 2015 earthquake can serve as an opportunity to evaluate the national capacity to respond to such disasters. This disastrous event in April of 2015 represents an opportunity because, according to Holguín-Veras et al. (2014), large-scale disasters are rare events that, even in disaster-prone countries such as Japan, often happen after many years and typically impact different jurisdictions. Various available empirical studies have highlighted the disaster policies, humanitarian responses, and lessons learned from the 2015 earthquake, focusing on international humanitarian responses, public health, community resilience, civil-military relations, and coordination and distribution of aid (Cook et al. 2016a; Hall et al. 2017; Thapa 2016). However, none of the studies has attempted to specifically explore the capacity of national institutions in terms of handling disaster response in the context of the 2015 earthquake. It is crucial that the national institutions for disaster risk management be as robust as possible and that practical implementation be efficient and effective (GoN MoHA and DPNet-Nepal 2013). This study aims to analyze the disaster management performance of the Nepal government’s responsible institutions right after the 2015 earthquake. It also seeks to identify the policies and guidelines that influenced their roles and, finally, the strengths and weaknesses of the responding government institutions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emergency Response after an Earthquake

A major earthquake can quickly drag the situation into great commotion as it is likely to be followed by numerous uncoordinated activities between groups with poor communication and confusion among the people concerning what to do (Coburn and Spence 2002). After the earthquake on 19 September 2017 in Mexico City, for example, volunteer rescue brigades and health groups came out instantly; however, it was found that due to the lack of coordinated information these skilled teams did not know where they were most needed (Fraser and Carvallo-Vargas 2017). Accordingly to Alexander, emergency planning encompasses a coordinated and co-operative process of preparation (Alexander 2015), and Coburn and Spence (2002) suggested that having a pre-earthquake emergency plan can be one of the best ways to ensure an effective response. Nevertheless, emergency plans should be realistic and pragmatic (Alexander 2015).

Emergency responses, on the other hand, are an effort to mitigate the impact of an incident on the public and the environment. A large-scale emergency event will demand the cooperation of several agencies (RI DEM 2008). The role of the government is crucial in an emergency response, for example, declaring an emergency and seeking international aid, providing support and protection, coordinating internal and external assistance, and governing relief work (Harvey 2010; Cook et al. 2016b). The final decisions on declaring emergency and request for international assistance rest with the national government (Coburn and Spence 2002). The Federal Emergency Management Agency has stated that an emergency response comprises actions that are taken to save lives and to prevent further property damage, whereas response itself means converting preparedness plans into action (FEMA 1998).

During the rescue and relief stage, the immediate focus is to save the lives of people, which can be done through the deployment of search-and-rescue teams (Kates and Pijawka 1977; Alexander 2007 as cited by Contreras 2016). Asokan and Vanitha (2017) emphasized the importance of a combined effort by aid agencies and health professionals in an emergency response. Further, needs assessments are vital for estimating the number of affected people from an earthquake, the number of temporary shelters required, and finally, the type of humanitarian aid required (Brown et al. 2010 as cited by Contreras 2016).

In the case of the Nepal earthquake, according to Bisri and Beniya (2016) the Nepali government through the National Disaster Response Framework 2013 did manage to call for international assistance and partially coordinated the emergency response operational activities. In response to the Nepali government’s international appeal for assistance, 34 countries rallied with 18 military and 16 non-military teams with a total force of 4521 people. The effort comprised an urban search-and-rescue team, engineers, air support personnel, and medical professionals (GoN MoHA 2015). India responded in less than 12 h and was the first international team to arrive in Nepal. China, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Bhutan as close neighbors followed (Cook et al. 2016a). The international media’s extensive coverage of the earthquake was instrumental in generating help (Fitzgerald et al. 2015).

On the other hand, the Nepal Army set in motion a rescue and relief operation named “Operation Sankatmochan” (GoN NA 2015). In that operation, about 66,069 Nepal Army personnel were deployed. As a result, 23,594 people were rescued. Out of these, 1336 people were rescued alive from collapsed buildings, and 2928 people were rescued by Nepal Army helicopters. In addition, the Nepal Army provided medical treatment to 85,954 individuals from the 14 most-affected districts and distributed 5707 tons of relief to 20 affected districts (GoN NA 2015).

However, the government of Nepal was unable to carry out the initial needs assessment in the wake of the 2015 earthquake. A lack of understanding of the needs, difficulty in communication and logistics, and a centralized approach to the response meant that many rural people did not receive support for several days (Hall et al. 2017). Relief arrived a week after the earthquake event in remote rural areas of Nepal (Sheppard and Landry 2016 as cited by Paul et al. 2017), and the government’s service delivery could not meet the expectations of communities (Paul et al. 2017 as cited by Adhikari et al. 2018).

The most outstanding challenges underscored were gaps in the supply chain, lack of local leadership, and coordination difficulties (Hall et al. 2017). The government, on the other hand, pointed toward geographical difficulties (hilly remote regions) and severely-damaged infrastructure as reasons for the delay in distributing relief (Paul et al. 2017). The district hospitals in severely-hit areas were badly damaged by the earthquake because of their design and low building standard (Chen et al. 2017). Du et al. (2016) in their study found that a high-altitude environment adds an extra burden to the relief workers in during earthquake relief and that relief workers can suffer injuries in such an environment.

To respond in an emergency, communities utilize available local resources collectively, which are mostly driven by mutual obligation and social bonding (Adhikari et al. 2018). In a case study of Lalitpur district,2 Khazai et al. (2018) found that more capacity-building programs are required for community, non-government organizations, and government officials to develop their emergency management skills.

2.2. Disaster Risk Reduction

In 2005, Nepal became a signatory to the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015, a global ten-year plan that focuses on building national and local resilience to disasters. Subsequently, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) 2015–2030 was endorsed by the UN General Assembly, which aimed at the reduction of disaster risk and loss of lives, livelihoods, and health (Etinay et al. 2018). As a member state to both the international commitments, the government of Nepal shows commitment to reduce disaster risk in line with the guiding principles of SFDRR. Disaster risk reduction has already been recognized internationally as an important global issue given the rising climate change in the world (Pathak and Ahmad 2018). The signing of these important global initiatives has helped the government of Nepal to establish various disaster risk reduction initiatives, for example, the National Strategy for Disaster Risk Management 2009, National Disaster Response Framework 2013, and Nepal Risk Reduction Consortium. Two key initiatives that have brought together the Nepalese government and external actors in the absence of strong disaster risk management are (1) the Nepal Risk Reduction Consortium and (2) the cluster approach of the National Disaster Response Framework 2013 (White 2015). Another significant accomplishment is the introduction of the Hospital Preparedness for Emergencies (HOPE) program in all the major public hospitals in Kathmandu city.

However, Tuladhar et al. (2015) found that the disaster risk reduction education initiatives implemented so far in Nepal are not sufficient. Tuladhar et al. (2015) argued that the disaster risk reduction programs run by international non-governmental organizations and national non-governmental organizations were full of jargons and may also be misleading. Gaire et al. (2015) stated that though Nepal seems to have participated in disaster risk management from 1982 until 2014, most of these activities have been limited to blueprint and that implementation has been problematic. The existing frameworks, rules, and regulations are neither fully funded nor fully enforced (Wendelbo et al. 2016). Therefore, more continuous efforts to educate people about disaster risks, funding, and tangible implementation policies and guidelines are critical areas in need of improvements.

2.3. Disaster Risk Governance

Disaster risk governance emphasizes having the institutional system, mechanisms, policy, and frameworks and arrangements to guide, coordinate, and monitor disaster risk reduction (UNISDR 2017). Disaster risk governance focuses on bringing the authorities, civil administration, media, the private sector, and civil society together to coordinate with communities to manage and reduce disaster and climate-related risks (Jones et al. 2014). In Nepal, governmental and non-governmental organizations are involved in disaster management, but they seem to lack clarity in terms of their responsibility, coverage of beneficiaries, and coordination at the local level such as with village development committees, and accountability (SiAS 2016). Other problems mentioned are a clear institutional mandate, multiple actors working in the field of disaster at the local level with fragmented resources3, the absence of local elected representatives, the limited capacity of local government staff, lack of linking disaster plans with local plans, external influences in planning (donor-driven plans), lack of preparedness (no equipment, tools or techniques), and lack of adequate scientific data (SiAS 2016).

Jones et al. (2014) noted that in Nepal, the government departments are protective of their interests, plus they are slow to enact policies to support DRR. That said, considerable progress has been made in the domain of DRR. One good example is the Nepal Risk Reduction Consortium (NRRC), which was formally launched in 2011 under the chair of the Home Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs to realize the institutional gaps (GoN MoHA and DPNet-Nepal 2013). Under NRRC, government and non-government actors work together on agreed priorities. Some of their achievements under their five flagship program areas are highlighted in Table 1. Bakkour et al. (2015) have suggested that the governance system should try to be adaptive to enhance the capacity of institutions in coordinating relief operations, public awareness, and risk reduction policy by learning from experience.

Table 1.

Nepal Risk Reduction Consortium’s flagship priority areas with key achievements.

2.4. National System for Disaster Management

The Natural Calamity Relief Act 1982 and the Local Self Governance Act 1999 are the key legal foundations for disaster response in Nepal. As mandated by Natural Calamity Relief Act 1982, Ministry of Home Affairs is the lead agency responsible for immediate rescue and relief work as well as disaster preparedness activities. The National Strategy for Disaster Risk Management (NSDRM) was formulated in 2009, and it offers strategic direction in handling all stages of the disaster management cycle. Unfortunately, during the 2015 earthquake the legal provisions for implementing the NSDRM were yet to be approved. Hence, the strategies drawn in NSDRM could not be put into effect.

In the case of a mega-disaster, upon the request of the Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee, the Cabinet can declare a state of emergency. The Disaster Rescue and Relief Standard 2007 states that the Natural Disaster Relief Fund shall remain active at the central, regional, district and local level. The Prime Minister Natural Disaster Relief Fund (PMNDRF) will be mobilized as per the PMNDRF Regulation 2007, whereas, the Natural Calamity Relief Act 1982 also mandates the formation of a Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee, a Regional Disaster Relief Committee, a District Disaster Relief Committee, and a Local Disaster Relief Committee. Further, a supply, shelter and rehabilitation sub-committee and a relief and treatment sub-committee are also established at the central level. The Local Self Governance Act 1999 provisions local bodies such as the District Development Committee, Municipalities, and Village Development Committees to be responsible for disaster preparedness and response (GoN MoHA 2013).

3. Methodology

This study was derived from field research using a qualitative method. It includes 58 key individual interviews, four focus group discussions, field observations, and document analysis carried out from December 2015 to August 2016. The data were generated through a combination of the triangulation method using the multiple sources of evidence. Primary sources of data were collected through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and field observations (public hospitals and government institutions) with key stakeholders that were directly involved in the response efforts after the April 2015 earthquake. These included the then Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister, military officers from various units including the military headquarter, military Air Service, and Nepal Army liaisons officers assigned to different foreign military units. Others that provided essential insights into the context included medical personnel from the government, public hospitals, and security forces, the ex–national police chief, senior bureaucrats such as secretaries, joint-secretaries, under-secretaries, chief district officers, a local development officer, and officials from disaster management section under ministry of home affairs, ministry of federal affairs and local development, ministry of education, and national planning commission. In order to verify and obtain the contrasting information, people were interviewed that were not central to the phenomenon (government officials) but were part of the event, such as the staff of the Nepal Red Cross Society, individual volunteers, team leader from an international humanitarian agency, disaster victims, local journalists, and the general public.

The semi-structured interview and focus group discussion checklist were designed to ask the following questions. While formulating the research questions, as advised by Creswell (2013), the authors reduced the entire study to a single overarching central question followed by several specific questions that will specify the central question in the areas of inquiry.

- Central Question:

Are government institutions of Nepal capable of coordinating the response to the large-scale disaster?

- Specific Questions:

- Based on your experience, what were the guidelines and policies the government followed to respond to the 2015 earthquake?

- Based on your experience, who was effectively involved in the emergency response? (Refers to government institutions.)

- Based on your experience, why did institutions respond in that way? Were they effective? Please elaborate.

- Based on your experience, how did the coordination mechanisms within the government ministry and departments work? What was the coordination like between the civil administration and the security forces? Please elaborate.

- During the immediate emergency response, what were the information-generating and sharing mechanisms that allowed the security forces and civil administrators to best respond to the disaster? Please elaborate.

- Based on your experience, what were the weaknesses and challenges you faced during the emergency response operation? Please elaborate.

- Based on your experience, what were the strengths of the Nepal government in coping with the large-scale disaster response?

The above seven specific questions were the means of subdividing the central question into several parts. These aforesaid open-ended specific questions were asked during the in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. In order to avoid psychological and career risks to the participants, the purpose of the research was explained, and confidentiality and anonymity were ensured to the security officials from the Nepal Army, the Nepal Police, and the Armed Police Force. The interviews and focus group discussions were held at their office premises. Secondary data were collected from official records, previous studies, books, publications, journal articles, policy documents, reports, and newspaper articles about the humanitarian emergency response, and disaster management endeavors and relief efforts before and after the 2015 earthquake.

3.1. Selection of Participants

Drawing a non-probability sample, purposive sampling was applied by only focusing on the key government institutions that were heavily engaged in emergency response. This approach of sampling emphasizes selecting only those participants whose characteristics are more likely to have some bearing on the research topic and relevant experience (Barbour 2008). The ideal size of a non-probability sample depends on the size of the research population as a whole and that no firm rules or guidelines can be given (Thiel 2014). In this light, the choice of participants was driven by the research questions and not by a concern for representativeness.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The interview guidelines suggested by Bailey (1994) and Thiel (2014) served as a checklist before and during the interviews to ensure that all of the required information and areas were covered. Applying open-ended questions, the interviews and focus group discussions were conducted in conversational Nepali language. The face-to-face interviews conducted on the office premises of the government officials lasted approximately 1 h, whereas, the focus group discussions conducted in the government complex and military barracks lasted 2 h. Each interview and focus group discussion was recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The transcribed information was meticulously studied and the data reduction technique was followed as suggested by Miles and Huberman (1994) through the summarization of the collected information. In order to reduce bias and to maintain data-quality checks, the bracketing approach of Tufford and Newman (2010) was carefully considered. After reducing the data to manageable chunks, the necessary interpretation was made descriptively. After descriptive coding, pattern coding was followed to pull together themes and more meaningful analysis of government institutions’ responses to the large-scale disaster.

Unobtrusive observational field visits to National Emergency Operation Center, Ministry of Home Affairs, and five major public hospitals such as Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Patan Hospital, Civil Service Hospital, Shree Birendra Hospital, and Bir Hospital were covered in order to see how the practices were enacted on a daily basis as it afforded an opportunity to view the behavior in a naturalistic setting (Barbour 2008). The above organizations were purposively selected, because of their extensive engagement in the emergency response to the 25 April earthquake. The main aim of the observation was to corroborate the findings of the in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and document analysis. An observation checklist was developed following the suggestion of Creswell (2013) to meet the standards of observation.

Finally, document analysis was also carried out to seek convergence and to corroborate the data derived from the interviews and observations. With reference to the central research question “Are the government institutions of Nepal capable of coordinating their response to large-scale disasters?”, it was essential to understand how the key government institutions were being prepared for disaster risk reduction, what policies and frameworks were available to manage such a disaster, who was assisting them with the disaster management, how they were participating, and what the drivers and barriers were.

3.3. Details of Participants

The above Table 2, shows the details of 58 participants who were personally interviewed in the study. On the other hand, focus group discussion one was comprised of five government officials, out of which two were Section Officers and one Under Secretary from the Disaster Management Division, Ministry of Home Affairs, and one was the Under Secretary, from the National Emergency Operations Center, and one Administration Officer from the Ministry of Home Affairs. Similarly, focus group discussion two included six veteran civil servants including one former Secretary of the Ministry of General Administration, three Local Development Officers, and one Under Secretary from the Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and one a former Chief District Officer. All of these government officials had work experience of more than 15 years.

Table 2.

Details of 58 interviewed participants.

Focus group discussion three was comprised of five Nepal Army officials that had closely worked with the District Disaster Relief Committee at the District Administration Office in one of the worst earthquake hit districts. Following strict military protocol, the participating officials were promised anonymity and confidentiality. Thus, the specific ranks, place, and names of all military officials were withheld in this study. The group discussion took place at the Nepal Army battalion which was stationed in the worst affected district.

Finally, focus group discussion four also included five Nepal Army officials. Out of them, three were army air service helicopter pilots flying rescue and relief missions from day one of the devastating earthquake. The other two were army officers posted in the airport to liaison with foreign military team.

4. Response Structure and Timeline

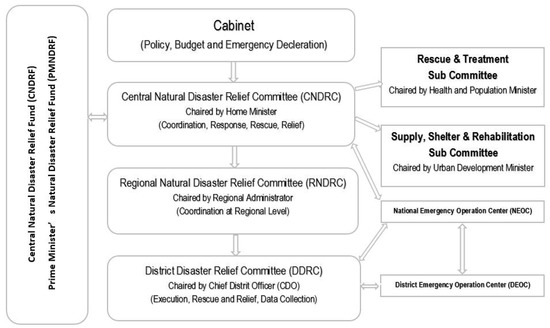

4.1. Government Institutional Arrangement for Disaster Management

The following Figure 2 describes the national disaster response structure at different levels of government (central, regional and district). The Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee (CNDRC) under the Cabinet is chaired by the Home Minister, Ministry of Home Affairs. Committee members include Secretaries4 of all key ministries such as Defense, and Foreign Affairs. The Prime Minister’s Natural Disaster Relief Fund (PMNDRF), seen in the left-hand corner, is set up by the government of Nepal for search and rescue, and to provide relief, and rehabilitation to the victims of a natural disaster. The funds are released through the Ministry of Home Affairs to the Chief District Officer (GoN MoHA, MoFALD 2014).

Figure 2.

Government institutional arrangement for disaster management. Source: Adopted from Koirala (2014); Ghimire (2015).

The regional administrator chairs the Regional Natural Disaster Relief Committee. The committee members include regional heads or chief of the security forces, the Health Directorate, Road Directorate, and the National Planning Commission. The Chief District Officer heads the District Natural Disaster Relief Committee. The committee members include the Nepal Army unit, the Armed Police Force unit, the Nepal Police unit, Public Health Office/Hospitals, Chiefs of all district offices, and the Nepal Red Cross Society. The major functions of the District Natural Disaster Relief Committee at the district-level are as follows: develop district-level disaster preparedness and response plan; coordinate between local authorities on disaster relief work; monitor the relief work of local communities and support them; implement the directives from central authority; deploy a search and rescue team in emergency situations; provide incident reports to the National Emergency Operation Center and the Ministry of Home Affairs; provide cash and other assistance to the affected population; and assess, collect, and disseminate information.

The Ministry of Home Affairs established the National Emergency Operations Center on 17 December 2010. Located next to the Ministry of Home Affairs’ complex in Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, it is operated under the Planning and Special Services Division of the Home Affairs Ministry.5 The National Emergency Operations Center’s objective is to be a focal point for coordinating and disseminating disaster-related information amongst government agencies and other non-government stakeholders. Establishing a District Emergency Operation Center is part of the strategy of the Home Ministry to develop the country’s emergency preparedness and response. Nevertheless, many districts in Nepal are yet to follow.

4.2. National Disaster Response Framework 2013

The National Disaster Response Framework 2013 is designed for effective coordination and implementation of disaster preparedness and response activities by clarifying the roles and responsibilities of government and non-government agencies involved in disaster risk management in Nepal (GoN MoHA 2013). Nevertheless, the scope of this framework is limited to preparedness and emergency response. The NDRF has domestic legal power and at the same time reflects international humanitarianism as it comprises the United Nations-led Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) humanitarian cluster approach (Bisri and Beniya 2016).

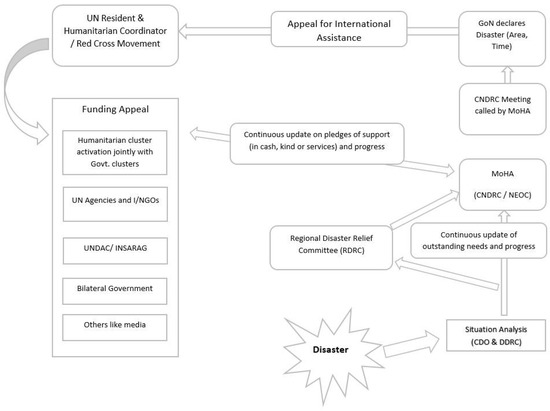

The National Disaster Response Framework states that in the event of a large-scale disaster, the UN Humanitarian Coordinator will activate the cluster system of Nepal. The GoN, on the other hand, will nominate the full-time focal person to the respective cluster to coordinate the response.

Figure 3, from National Disaster Response Framework, shows the coordination structure for a mega-disaster that requires international assistance. It is stated that during a large-scale disaster, the government of Nepal may request the UN Humanitarian Coordinator, national and international governments, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), regional organizations, donor communities, international and national non-governmental organizations, political parties, resident and non-resident Nepalese citizen, foreign citizens, and other sources for international assistance in terms of cash or services (GoN MoHA 2013).

Figure 3.

National and international assistance and coordination structure during an emergency. (Note: Acronyms.6 Source: GoN MoHA (2013).

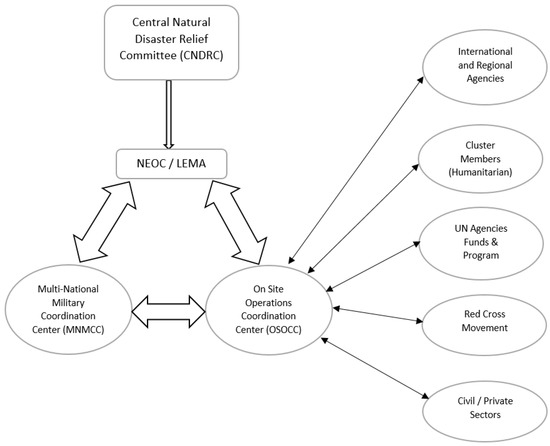

In Figure 4, the role of the Multi-National Military Coordination Center (MNMCC) was given to the Nepal Army. The role of the On-Site Operations Coordination Center (OSOCC) was assumed by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The Ministry of Home Affairs, in coordination with the National Emergency Operation Center, was to overlook the MNMCC and OSOCC.

Figure 4.

Coordination mechanisms between international and national actors. (Note: Acronym.7 Source: GoN MoHA (2013)).

Finally, the National Disaster Response Framework outlines 61 operational activities to be implemented for emergency response after its activation, and allocates responsibilities to lead agencies for implementation using designated timeline (Bisri and Beniya 2016; GoN MoHA 2013).

4.3. Timeline of the 2015 Earthquake

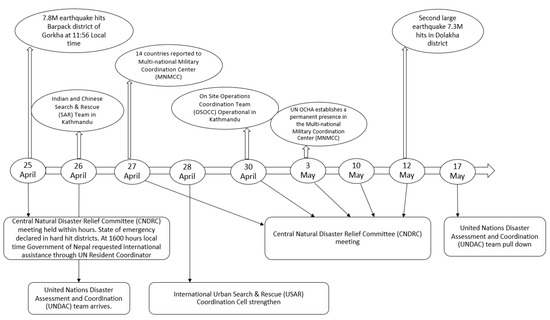

Figure 5 reflects the timeline of government and international response to the 2015 earthquake.

Figure 5.

Timeline of the 2015 earthquake. Source: GoN MoHA (2015).

5. Results

The results are grouped into themes constructed with reference to the research aim and on the basis of the National Disaster Response Framework 2013’s coordination mechanisms. These themes are based on the statements collected from the in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. The results incorporate the views of participants with reference to the Nepal government’s emergency response in the aftermath of the 2015 earthquake. The following section describes the themes such as followed policy, guidelines, coordination mechanisms, strengths, and key weaknesses.

5.1. Policy and Guidelines

The statements from various civil administrative officials indicated that government institutional arrangement for disaster management (see Figure 2) became a handy platform to deliver emergency responses—for example, the Cabinet (emergency declaration), the Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee (central level coordination), the District Disaster Relief Committee (district-level coordination), the National Emergency Operation Center8 (central level information hub), and the Prime Minister’s Natural Disaster Relief Fund (immediate cash flow). The interviews indicate that since the institutional setup for disaster management was on the basis of the old established Natural Calamity Relief Act 1982, the arrangements were well known to all government officials. Hence, this setup became handy.

The responses from the interviews and focus group discussion one9 points out that the government of Nepal in the 25 April 2015 earthquake disaster, quickly followed the National Disaster Response Framework 2013 guidelines (see Figure 3 and Figure 4) to call for international assistance and coordinate the immediate emergency response. That said, besides following those guidelines, the government also made bilateral approaches to India and China.10 One section officer from the Disaster Management Division, Ministry of Home Affairs stated the following:

Without the National Disaster Response Framework 2013, we could have gone haywire in responding. Thank god the framework was there at least.

5.2. Coordination Mechanism (Refer to Table 3 and Figure 3 and Figure 4)

Table 3.

Cluster coordination structure involving government and non-government humanitarian agencies.

Though the National Disaster Response Framework 2013 guidelines were designed for effective coordination between government and non-government actors, the respondents revealed that they did not fully function as intended. According to the responses, cluster coordination (see Table 3) gaps were identified with the Ministry of Health and Population; the Ministry of Urban Development; the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare; and the Ministry of Agriculture Development. The civil administrators reported that these ministries were unable to immediately coordinate their expected responsibilities as prescribed in National Disaster Response Framework 2013, so in their absence, the Nepal Army quickly took over to fill those gaps.

Statements from focus group discussion two11 and the interviews indicated gaps that were due to civil administrators lacking directives through clear-cut policy and allocation of resources (financial, technical and skills), as can be seen in the words of a former Chief District Officer who was also a former Secretary:

Firstly, we do not have a clear policy and guidelines describing the detailed roles and responsibilities to address disaster situation. Second, we do not have adequate knowledge, experience and resources. Third, we lack coordination within our government ministries and departments.

However, the coordination mechanisms between the international and national actors (see Figure 4) were handy in allocating responsibilities amongst the central government, the Nepal Army and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). Yet, it was reported that due to some organizational differences amongst the actors, the coordination framework became distorted and was no longer what had been envisioned. For example, in Figure 4 it can be seen that the On-Site Operation Coordination Center, as the responsibility of the UNOCHA, could not be established at the same pace as the Multi-National Military Coordination Center (MNMCC). A Nepal Army officer in an interview pointed out that the role of the National Emergency Operation Center, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 4, was facilitated by the Directorate of Military Operations, based at the military headquarters. The officer claimed that in fact, the Directorate of Military Operations was spearheading the MNMCC, airport coordination, the National Emergency Operation Center and the units on the ground under the command structure of the Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee. The field observations12 of the National Emergency Operation Center (NEOC) complex corroborated the fact that it was under-staffed with only one member of the Nepal Army security personnel in the communication room. On the other hand, the NEOC was supposed to be the key information-generating and sharing hub for the disaster management between the civil administrators and security forces. One section officer from Ministry of Home Affairs stated the following in this connection:

At NEOC, the information that we usually received was from District Disaster Relief Committee, Nepal Police and Armed Police Force. Thus, we did not get much information from the Nepal Army, and since the Army took over the leadership on the ground, they were coordinating more from the military headquarter.

The above statement indicates that there was some tension or gaps between the civil administration and the military in terms of coordinating and reporting, as the Nepal Army is not under the Ministry of Home Affairs. Nevertheless, all of the respondents quickly agreed that the security forces under the leadership of the Nepal Army played a crucial role in establishing law and order and in coordinating the humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations. However, the respondents also talked about the search and rescue (SAR) works carried out by the national security personnel and foreign SAR teams, indicating that they were slow and inadequate as they failed to reach the remote areas of the country in time. The majority of local newspapers13 and disaster victims were critical of the government’s slow response in remote areas.

5.3. Strengths

According to the findings, it was evident that the years of disaster risk reduction (DRR) efforts put in place by non-state agencies paid off. For example, the respondents from the health sector confirmed that the “Health Sector Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Response Plan Nepal” prepared in 2003 by emergency managers in the Disaster Health Working Group had significantly prepared and injected the importance of emergency management in hospitals. The senior medical directors talked about the positive role of the World Health Organization of the United Nations, non-government organizations and donor agencies positive role to support (financially and technically) the government of Nepal. The responses indicated that under their programs, the major public hospitals in Kathmandu city such as Shree Birendra Hospital, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Patan Hospital, Civil Service Hospital, and the Bir Hospital had retrofitted their buildings and introduced Hospital Preparedness for Emergencies programs. The efforts—for example, structural and non-structural adjustments as mentioned in GoN and WHO (2004), were visible during the field observations conducted at these public hospitals. Interviews with medical personnel confirmed that the public hospitals conducted regular drills as per the HOPE program which in turn helped them to cope with the 2015 disaster. Professor Deepak Mahara, Executive Director of the Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, stated that their HOPE plan had been carried out regularly and that it helped. Similarly, Dr. Paras Kumar Acharya, Vice Chancellor, Karnali Academy of Health Sciences, and a former Director of Patan Hospital, reiterated that Patan Hospital has a hospital emergency preparedness plan. Additionally, they also perform HOPE drills regularly, as he indicated in the following interview excerpt:

Those hospitals, which conducted drills earlier, were able to activate the emergency operations more quickly as opposed to those that had written plans but never rehearsed.

The respondents agreed that the formation of the Nepal Risk Reduction Consortium in 2011 was a success in terms of bringing government and non-government actors together to reduce Nepal’s vulnerability to a natural disaster (NRRC Secretariat 2012; GoN MoHA and DPNet-Nepal 2013; Taylor et al. 2013). Some of the achievements under their five flagship program areas are highlighted in Table 1.

Interestingly, it was stated by the senior medical representatives that one of the key factors for the successful performance of these public hospitals in Kathmandu was having medical colleges, for example, Patan Academy of Health Science, Patan Hospital; Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital; Nepalese Army Institute of Health Sciences of Shree Birendra Hospital; and National Academy of Medical Science of Bir Hospital and Manmohan Memorial Institute of Health Sciences affiliated to Tribhuvan University. All of these medical colleges were instrumental in providing skilled human resources (resident students). The director of Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital and Patan Hospital mentioned that, despite outside offers, they did not accept external medical professionals as their internal staff and students were sufficient to handle the emergency.

On the other hand, the total security forces comprising the Nepal Army, the Nepal Police, and the Armed Police Force became one of the biggest assets to the government, as an ex-police chief indicated:

Sharing their professional obligation, one military commander deployed in the remote district of Kavre added the following:The security forces are an organized and disciplined force amongst all. Thus, the deployment of these forces was highly effective in comparison to others. Since they follow a unitary command system, all the troops can be mobilized with one single order.

Finally, the majority of the respondents talked about a strong sense of solidarity in the community as one of the key strengths and the motivated youth volunteers.Our soldiers’ own families were victims, but they could not go home because they were deployed with us. As a commander, I know their feelings, but we have to follow the orders.

5.4. Weaknesses

Despite the commendable efforts, serious limitations in the government institutions came to the surface from the statements of the respondents, who highlighted the key shortcomings at the central, district, and local level as follows: lack of clear-cut policy, lack of budget to implement the existing policies, lack of leadership; political instability, lack of communication and coordination between ministries and departments, low staffing and high staff turnover; lack of necessary training; absence of local-level representatives, lack of trust from general public, and lack of knowledge and information. During the field observations at the Ministry of Home Affairs complex, only a few staff members were observed in the Disaster Management Section, one designated staff member in the Disaster Research and Development Section and two at Disaster Risk Reduction Section. Similarly, Jones et al. (2014) confirmed low staffing at the ministry level as a key challenge.

Citing the problems of understaffed local bodies, a former Local Development Officer and currently a Joint-Secretary from the Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development (MoFALD) stated the following:

Further, one Local Development Officer pointed out the problems with the absence of elected representatives at the local level, which he claims to have created coordination difficulties for them. He stated the following:In our old existing institutional setup, a Village Development Committee Secretary is a responsible government representative to coordinate reliefs at the village level. During the time of disaster and since long, the country did not have enough Village Development Committee Secretaries. How can you coordinate activities to the village when there are no representatives? Another constraint is monetary as it requires money to send or assign someone to visit the village. For that, we do not have a separate budget.

Local level elections14 have not been held for more than two decades. If we had local representatives like Village Development Committee Chairman and their team such as Ward Chairman, Ward members, and Ward secretaries at the village, the district, and central administration (PDDP 2002) will have a clearer picture of the local problems.

The responses from focus group discussions two and, three15 and the interviews revealed that even among the members of the District Disaster Relief Committee, roles and responsibilities were not clearly defined. It was mentioned that at District Disaster Relief Committee meetings, responsibilities were assigned on an ad-hoc basis. For example, the Nepal Police were asked to solve problems that were considered less severe, whereas, more sensitive and severe problems were handed over to the military. This also indicates that the military is normally called upon to solve the complex tasks beyond the reach of other security agencies.

In reference to the helplessness of civil administrators in the district, one senior District Administrative Office official stated the following:

Assume that we have an emergency flood situation, and that we needed to evacuate the villagers from a certain area. As our process, we will call the District Disaster Relief Committee (DDRC) meeting at District Administration Office. The DDRC committee members would then agree and decide on evacuating the people. However, at that point, our security officials will state that before their deployment, they are required to take the final permission from their respective headquarters. Therefore, in such cases, though we already decide for executing a plan at DDRC, it will not go into immediate execution and that can also create delays.

Concerning the suggestions for strengthen future disaster response at the DDRC, a district Chairman of Nepal Red Cross Society stated the following:

The responsible district officials like Chief District Officers and Local Development Officers should have adequate knowledge in the field of disaster management. For example, the work procedures under disaster scenarios and knowledge of available policies and guidelines.

He shared the idea that the officials in his district were not aware of the National Disaster Response Framework’s cluster approach. Thus, in the early phase of the emergency response, the district officials tried to address the entire problem by themselves without asking for the assistance of other responsible cluster partners and the burden was too much for them.

Clarifying the civil administrators’ difficulties, a district administrative official stated the following:

In a district office, Chief District Officer is responsible for numerous tasks. For instance, head various committees, sign all the issued citizenship cards, and passports, and resolve the complex public-private disputes. Besides, the Chief District Officer also take on coordination works from monitoring and evaluation of the programs to entertaining the inbound guests. Chief District Officer is a single person and how do you think they will perform given the responsibility of disaster management on top?

The following are the major weaknesses discussed about the security agencies: lack of civil-military relation; lack of search and rescue equipment; lack of necessary training; and not enough helicopters. While analyzing the document source (official presentations of major public hospitals on 2015 earthquake experience16), it was interesting to find that only the military hospital “Shree Birendra Hospital” had not received any outside support. In contrast, the other four public hospitals had received support in the form of cash, free meals, drinking water, volunteers, and blood donations made by civil society groups, and private sectors and individuals. This finding also proved that there were indeed some gaps in communication between the military and civil society. In fact, during the discussion, the military officials were more concerned about their hospital’s peripheral security being breached by civilians.

Citing the lack of search and rescue tools, one of the front-line search and rescue responders deployed in Kathmandu from the Nepal Army added the following:

Forget about big equipment and technology, we did not even have concrete drilling machines and sufficient generators. We used our bare hands. The international SAR teams were well equipped. We had never seen those types of machinery, we learned much by seeing them.

While talking with the field-level security responders, they stressed that they faced difficulties in distributing the relief materials on site due to the variety of materials for distribution (food, blankets, tents, and tarpaulins) and also due to miscommunication. For example, the number of recipients was always lower than the actual number, resulting in tensions on the ground. A battalion commander of the Nepal Army posted in one of the crisis districts added the following:

Initially, the collected relief materials were distributed haphazardly in the district without any monitoring system as we also lacked experience and the time was ticking. The early relief materials did not go thru one door policy as instructed by the central authority. It was not possible for us at the District Disaster Relief Committee to immediately apply the system without experience, which demanded a slow process to pass through bureaucratic and administrative steps.

The above claim indicated the fact that the authorities at the central level were making decisions without receiving feedbacks from the field-level. It exposes the usual top-down approach culture in the administration without much concern about the local-level reality.

Interestingly, most of the field-level coordinators from the security agencies and District Disaster Relief Committee members from affected districts strongly favored the government’s one door policy (Pokharel and Niroula 2015). They claimed that it was a good move for equity and dispute resolutions despite the huge public outcry.

Regarding the public hospitals, the following were the key weaknesses recorded in the discussions: lack of an inter-hospital information sharing system; personnel planning (medical and non-medical staff duty roster), lack of an adequate budget; lack of transport vehicles, inadequate waste management; inadequate medical supplies, lack of a detailed disaster management plan, inadequate regular disaster drill, and lack of a well-equipped field hospital and field ambulances.

An executive director of a public hospital stressed the importance of inter-hospital communication system between hospitals in the country and remarked the following:

While hospitals had their own internal emergency preparedness plan, there existed no communication and coordination system amongst hospitals. If we had an inter-hospital communication and coordination system, we could have worked more efficiently. For instance, prompt referrals to appropriate hospitals.

Another director of a public hospital criticized the government and added,

We did everything from our side to treat the victims and exhausted all our resources. But not a single authority visited us to ask how we were doing and if we needed any help.

After the devastating earthquake, the Ministry of Health and Population instructed all public and private hospitals, including nursing homes in the capital, to remain open and provide free treatment services to all the disaster victims (GoN MoHA 2015). The majority of public hospital directors during the discussion complained that the private hospitals during and after the disaster were not cooperative. They voiced that the government-run health care facilities were more reliable in a disaster than the private sector health services. In response to the concern about the performance of private hospitals, a medical doctor from the Armed Police Force who also works part-time in a private hospital stated the following:

Private hospitals and nursing homes in Kathmandu could not give the services like public hospitals because they do not have sufficient human resource. Most of them usually outsource more than 80 percent of their core medical staff, and they have only a few full time in-house medical doctors.

The doctor further clarified the issues of free treatment expenses and added the following:

Private hospitals were not sure how much the government would reimburse. Despite the confusions, Vayodha and Alka Hospital did provide services to the inbound victims, but due to the chaotic influx, they could not keep the records as to how many they treated. The government later offered around USD 5000 to compensate which was less than they had actually spent.

Opposing this statement, a senior medical representative (public health specialist) from the Ministry of Health and Population argued that most of the private hospitals were quick to show a long list of patients they had treated. In reality, discrepancies appeared in their claims: for example, there was duplication of names in the triage17 system, i.e., the same names were registered more than once in different categories such as in the red zone and yellow zone. The medical respondents also mentioned that there was no plan for managing the volunteers, as indicated by a public health specialist and an Instructor from Shree Birendra Hospital in the following interview excerpt:

Upon receiving the international medical team, we required more helping hands. Thus, we announced through FM18 Radio asking for volunteers having knowledge in Public Health. In response, hundreds of public health students, teachers and youth from Kathmandu showed up the next day. However, we could not use them as we had no plan to manage large numbers of volunteers.

Regarding the Tribhuvan International Airport’s air traffic management, the discussion in focus group discussion four19 indicated that the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal20 was not prepared for emergency air traffic management, as a Nepal Army wing commander suggested:

First, the air traffic controllers at Tribhuvan International Airport struggled to control the foreign military air crafts. No one knew who should control them at the airport. The Americans, Indians and Chinese flew in their own way. Nobody had time to explain to them the runway layouts, crossing procedures, the points where they could and could not go. Second, when big aircraft like the Hercules arrived at Tribhuvan International Airport, they had no appropriate forklifts to offload them. Consequently, it occupied space in the crowded airport which then delayed other aircraft en route. Third, the airport did not have proper storage facilities.

When asked about the most challenging key issue he faced as a top leader, former Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister Honorable Mr. Bam Dev Gautam21 added the following:

I was annoyed by our media, their negative news on the Government’s response was not helpful. They should not vent negativity at the time of national crisis, which will only help to increase public anger. It not only made difficult to coordinate the necessary response but also created misunderstanding amongst the public and the international community.

The comments from this top leader indicate that the media can influence the work of the government by amplifying negative news. Further, from the analysis of the document sources, it was evident that the majority of the local media focused on the negative aspects of the government’s capacity to handle the crisis and mocked its disaster preparedness. The respondents in this study talked about their experiences during the response to the 2015 earthquake, particularly highlighting the key government systems, policy, frameworks, and institutions such as the Natural Calamity Relief Act 1982, the National Disaster Response Framework 2013, the Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee, the District Disaster Relief Committee, and the security agencies and public hospitals that could help to effectively respond to the emergency crisis and help the disaster victims. At the same time, it also provided insight into the usefulness/limitations of policies and guidelines, coordination mechanisms, and institutional strengths and weaknesses.

6. Discussion

The findings show that the functioning of the key government institutions and institutional arrangements—such as security forces, major public hub-hospitals, the Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee, and the District Disaster Relief Committees under the Ministry of Home Affairs—was remarkable. They were able to save many lives and also alleviated the suffering of the people. The National Disaster Response Framework 2013, a UN-led coordination structure, was a useful guide in directing and coordinating the immediate response. Nonetheless, it should be noted that having such guidelines alone is not sufficient and that the given procedures in the guidelines should be practiced or exercised amongst key stakeholders. Such an effort will make sure that coordination gaps such as cluster responsibilities, civil and military relations, and institutional limitations at the central, district, and local level can be identified in advance. Without the massive deployment of security forces,22 the disaster response mechanisms may have malfunctioned or may have been ineffectual in responding to the crisis. As a result, the disaster could have had far more severe consequences such as the loss of more lives and the loss of public confidence. The poor emergency response in disaster situations can double, treble or multiply 10-fold the death toll of an earthquake (Coburn and Spence 2002).

The disciplined security forces and the unwavering services of trained medical personnel from major public hub-hospitals emerged as the strongest pillars of government response to the disaster. That said, the success also depended on the years of continuous efforts made by international organizations, namely, the United Nations Development Program, the World Health Organization, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and local NGOs and INGOs, which have been consistently active in disaster risk reduction efforts. For example, the Health Sector Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Response Plan in 2003 and the introduction of the National Risk Reduction Consortium 2011 and its flagship programs for disaster risk reduction in Nepal brought together the government and non-government actors. Nonetheless, success was also due to the solidarity of the international humanitarian community, and the contribution of the civil society, individual volunteers (youths), the private sector, and the national and international media. Comments from top politicians strongly suggest that the role of the media should not be overlooked at any level of emergency management as they can be helpful, complementary, or critical (FEMA 1999).

The gaps in the civil administration’s input became apparent mainly because of the civil administrators’ failure to issue clear directives through clear policy, lack of prompt decision-making power at district and local level, lack of resources (skilled human, technical, and financial), and disaster-related knowledge. Gautam (2013) asserted that the civil administration is usually not properly geared up for an effective response. He emphasized that discipline and efficiency are of the first order in disaster response and relief tasks, which are often dangerous missions, and that the military that cultivates these qualities steps in to fill the vacuum left by the government in post-disaster operations. However, Gautam (2013) also warned that a tendency to over rely on the military hindered the development of the initiatives, responsibility, and accountability of the civil government and officials.

Likewise, Garge et al. (2015) stated that the Government of India, in its numerous initiatives to respond to natural disasters, is often slow and inadequate in its operations. Therefore, the armed forces are frequently requested to assist the civil administration in relief-driven disaster management processes (Shivananda and Gautam 2005 as cited by Garge et al. 2015). Their study revealed that the Indian armed forces personnel are always the first choice of any state civil authority in disasters due to their high-quality training and effective execution of command, control and communication. It was also found that the flood event in Jammu and Kashmir in September 2014 highlighted the incompetence of the civil administration with regard to handling the crisis. All of these findings indicate the importance of having disciplined and trained security forces for disaster emergency response. The respondents also stated that the all-out mobilization of security forces under the leadership of the Nepal Army was crucial for the large-scale emergency response. It was somewhat interesting to note the perception of a civil servant (Local Development Officer) during an interview:

It is by default the duty of security forces to take care after rescue and relief operations as they are trained forces.

The new Disaster Management Act of Nepal, which reportedly addresses modern day disaster cycles (the draft was submitted to the Constituent Assembly in 2015) was endorsed by the parliament in September 2017 (Pradhan 2017). This incident itself reflects the slowness of the government of Nepal to achieve the goals of the DRR. According to White (2015), even for those countries with disaster policies in place, the actual implementation of these policies and the establishment of mechanisms required to support them are still areas in dire need of improvement. Looking at the current limitations of the central, district, and local-level governments and the pessimism of government officials and other non-government stakeholders, it is very unlikely that the goals and objectives of the new Disaster Management Act will be met as intended.

White (2015) argued that international observers are worried about the intensive “hand-holding” of the government through the flagship model. This may have negative consequences, substituting the government and, thus, reducing national incentive to establish disaster response as a core government priority in the future. The findings from this study support this statement to some extent (for example, deepening dependence) but also offers somewhat conflicting views. For example, had the UN and donors not shown interest and implemented disaster risk reduction programs in Nepal, the results of the 2015 earthquake emergency response may have been negative. Moreover, if the UN or other donors decide to pull back, given the present political, economic, and social condition, it is highly unlikely that Nepal can make progress on disaster risk reduction by itself.

Regarding international humanitarian assistance, according to Harvey (2010), international relief efforts have often been criticized for ignoring or undermining local capacities. Examples of this are the flooding of disaster zones with international workers, who failed to coordinate properly with host governments and showed little respect for local government officials. For instance, in Haiti, there was a lack of initial close cooperation between national and international relief agencies because many Haitian government agencies felt that they were excluded from humanitarian coordination and decision making (Grunewald and Binder as cited by (Harvey 2010)). It was also found that the Tsunami Evaluation Coalition review of the response to the 2004 Asian tsunami pointed out that local institutions were frequently neglected and undermined by the influx of international organizations. Besides, government regulations may also facilitate or impede the international relief effort (Harvey 2010). Fortunately, these were not the issues in the case of Nepal, thanks to the National Disaster Response Framework 2013 guidelines, which were followed quickly by calling for international aid by utilizing the presence of the UN Residence and Humanitarian Coordinator. Further, it was also evident that the key institutions such as the Nepal Army, and the Ministry of Home Affairs also followed the National Disaster Response Framework procedures through the directives of the Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee for coordinating the international humanitarian assistance. In the same spirit, the UN Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator played a crucial role in coordinating the international humanitarian support as per the agreed guidelines.

Mr. Richard Friedericks,23 an international humanitarian team leader from Portland Fire and Rescue, United States, shared his positive experience as follows:

We arrived at Tribhuvan International Airport two weeks after the 25 April 2015 earthquake and cleared the immigration normally with no complaints. Throughout our time in Nepal, we were welcomed and supported by the people. There was no interference by government or security personnel. I think the government was eager to be as helpful as possible toward relief teams come to help.

The remark below from Col. Joseph Martin, of the United States Air Force, sums it all:

Nepal saved Nepal, and the Nepalese can be justly proud of their ability to respond and recover. They can be equally satisfied knowing that the international community wanted to—and was allowed to—assist (CFE-DMHA 2016).

The respondents from below security sectors pointed out that below Nepal Army needs to make improvements in its civil–military relationship for better coordination with non-military partners. The same was also highlighted by Subba (2015) and CFE-DMHA (2015). This was also stressed by Thapa (2016) and the military officers in the focus group discussion. According to Metcalfe et al. (2012), the differences in below culture of below military and humanitarian actors present a major challenge to effective interaction. In the words of John Holmes, Emergency Relief Coordinator and United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs:

Coordination between civilian and military actors is essential during an emergency response. The increasing number and scale of humanitarian emergencies, in both natural disaster and conflict settings, has led to more situations where military forces and civilian relief agencies are operating in the same environment.

Finally, it was evident from the statements of respondents that the country’s youths and ordinary citizens who generously volunteered their time, knowledge, skills, and resources were very helpful during the aftermath of the 2015 earthquake. Whittaker et al. (2015) also stressed that unsolicited volunteers will be active in the times of crisis and that it is vital that emergency services and other organizations have a plan and are prepared to coordinate with them. IIGR (2014), citing Japanese and American past experiences, also emphasizes the importance and advantages of volunteers in disasters.

7. Conclusions

This article provides insights into the Nepal government’s emergency response to the 2015 earthquake based on interviews, focus group discussions, document analysis, and observations. The findings suggest that while calling for international assistance, the government failed to make a preliminary assessment of its existing institutional capabilities in terms of strengths and weaknesses to deliver prompt emergency management. As a result of its hasty appeal, the government was overwhelmed by a large number of incoming international military and non-military humanitarian teams and aid items, which created a burden in terms of coordinating their support and distribution. For example, Tribhuvan International Airport was overwhelmed with relief materials, many of which were unnecessary and unhelpful items such as canned food (not suitable for the Nepalese culture) as well as unnecessary medicine and clothing items.

The Nepal Army stood as the reliable national institution that demonstrated the prerequisite skills, disciplined human resources, and logistics, which remained of great importance for an immediate response. Correspondingly, the institutional systems such as the Central Natural Disaster Relief Committee, the District Disaster Relief Committee, under the Ministry of Home Affairs and all five major public hub-hospitals could also function and perform effectively. However, it was evident that they also had serious limitations that need to be addressed by the government of Nepal.

An effective response to a large-scale disaster requires sincere cooperation and coordination on the part of various stakeholders. This includes central to local government civil administration, security agencies, public hospitals, international humanitarian agencies (military and non-military), local NGOs/INGOs, bilateral aid from neighboring countries, international agencies such as the UN, and donors. It also demands the active participation from civil society, communities, and the private sector, including the important media (national and international). This, however, would demand a huge authoritative coordination mechanism between national and international humanitarian actors, which needs to be carefully planned and rehearsed by the state beforehand. Essentially, there should be reliable state institutions and systems for coordinating and communicating emergency responses which would minimize the confusion amongst national and international responders, and duplication of work, thus bringing about an effective response.

Though this study offers insight into the Nepal government’s institutional capacity to respond to a large-scale disaster, it has some of the limitations. The study incorporates only the personal viewpoints of those government officials that were purposely selected from the effectively responding government institutes and the findings were based on the inductive inquiries of those individual respondents. Therefore, it is not appropriate to generalize the Nepal government’s institutional capacity from this research to other government ministries and departments that have not been covered in this study, for example, the Ministry of Urban Development, Ministry of Health and Population, and the Ministry of Agriculture Development, the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare. They are also the responsible government’s organizations in the cluster coordination structure of National Disaster Response Framework. Further research is hence needed to determine the capacities of all missing government ministries and departments from the central to the local level in dealing with large-scale disaster emergencies.

In light of the current weaknesses, the following recommendations are made to the national government and its institutions to mitigate future losses due to disasters. A sufficient budget should be allocated to implement disaster management policies, including the regular training of government officials. Guidelines, if any, must be well explained to all key stakeholders and their implementation regularly practiced amongst the relevant institutions and non-government partners.

The cluster coordination partners must have a system to meet periodically and go through drills in order to identify their respective practical limitations. Fragmented efforts to reduce disaster risk on the part of various non-government actors should be streamlined with the government’s national plan. Further, a volunteer management plan must be developed in advance in order to utilize the potential of volunteers better. The local media needs to be more engaged in every disaster risk reduction effort as their engagement will ensure that they have good knowledge of the limitations of the country’s disaster management capacity, which will ultimately inform the public. The Nepal Army should prioritize the development of strong civil–military relations. This initiative may be started from the Shree Birendra Hospital itself by establishing a dedicated desk to network with civil society. Necessary search and rescue equipment, as well as capacity building programs, should be provided to all security forces regularly.

Regarding the public hospitals, an inter-hospital communication system must be established for all major public hospitals. Detailed hospital emergency plans including regular drills for emergency management, must be prepared by all hospitals and necessary medicines should be stocked for future disasters. Additionally, the government must allocate a budget in order to fund well-equipped field hospitals and field ambulances. Lastly, the government must empower the central, district, and local-level bodies by allocating a sufficient budget and providing necessary training to the designated officials. An information-sharing and communication channel must be improved within government ministries and departments at all levels. Individuals with necessary skills must be designated to departments such as the National Emergency Operation Center, the Disaster Management Division, the Ministry of Home Affairs, the District Administrative Office, and the Village Development Committee.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.; Methodology, B.S.; Software, B.S.; Validation, B.S.; Formal Analysis, B.S.; Investigation, B.S.; Resources, B.S.; Data Curation, B.S.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, B.S.; Writing-Review & Editing, B.S., P.P.; Visualization, B.S.; Supervision, P.P.; Project Administration, B.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all the key informants from the government departments, security forces, and medical professionals who shared their valuable time and insights during the field work in Nepal. Finally, for their comments and guidance, we would like to thank Dietrich Schmidt-Vogt, Theeraphong Bualar, and Vineeta Thapa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adhikari, Mina, Douglas Paton, David Johnston, Raj Prasanna, and Samuel T. McColl. 2018. Modelling Predictors of Earthquake Hazard Preparedness in Nepal. Procedia Engineering 212: 910–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, David. 2007. ‘From Rubble to Monument’ Revisited: Modernized Perspectives on Recovery from Disaster. In Post-Disaster Reconstruction: Meeting Stakeholder Interests. Firenze: Firenze University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, David. 2015. Disaster and Emergency Planning for Preparedness, Response, and Recovery. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokan, G. Vaithinathan, and Asokan Vanitha. 2017. Disaster Response under One Health in the Aftermath of Nepal Earthquake, 2015. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health 7: 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, Kenneth D. 1994. Methods of Social Research. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bakkour, Darine, Geoffroy Enjolras, Jean Claude Thouret, Robert Kast, Estuning Tyas Wulan Mei, and Budi Prihatminingtyas. 2015. The Adaptive Governance of Natural Disaster Systems: Insights from the 2010 Mount Merapi Eruption in Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 13: 167–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, Rosaline. 2008. Introducing Qualitative Research: A Student Guide to the Craft of Doing Qualitative Research. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bisri, Mizan Bustanul Fuady, and Shohei Beniya. 2016. Analyzing the National Disaster Response Framework and Inter- Organizational Network of the 2015 Nepal/Gorkha Earthquake. Procedia Engineering 159: 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Daniel, Stephen Platt, and John Bevington. 2010. Disaster Recovery Indicators: Guidelines for Monitoring and Evaluation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Centre for Risk in the Built Environment (CURBE), Available online: http://www.carltd.com/sites/carwebsite/files/CAR Brown Disaster recovery Indicators.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- CFE-DMHA. 2015. Emerging Challenges to Civil-Military Coordination in Disaster Response. Liaison: A Journal of Civil-Military Disaster Management and Humanitarian Relief Collaborations 7: 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- CFE-DMHA. 2016. Anatomy of a NGO Response Lessons from the Logistics Cluster. Liaison: A Journal of Civil-Military Disaster Management and Humanitarian Relief Collaborations 8: 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hao, Quancai Xie, Biao Feng, Jinlong Liu, Yong Huang, and Hongfu Chen. 2017. Seismic Performance to Emergency Centers, Communication and Hospital Facilities Subjected to Nepal Earthquakes, 2015. Journal of Earthquake Engineering. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, Andrew, and Robin Spence. 2002. Earthquake Protection. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, Diana. 2016. Fuzzy Boundaries Between Post-Disaster Phases: The Case of L’Aquila, Italy. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 7: 277–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Alistair D. B., Maxim Shrestha, and Zin Bo. 2016a. International Response to 2015 Nepal Earthquake Lessons and Observations. NTS Report. Singapore: NTS. [Google Scholar]