The Semiotics of the Evolving Gang Masculinity and Glasgow

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Gang Dynamics

4. Research Methodology

5. Results

6. Themes

6.1. Youth Street Gangs as Territorial

‘There wasn’t much to get up to when [growing up]. Nothing to do but get into trouble I suppose. Most of the daft gang fights I was involved in was more to do way breaking boredom than anything else.’—Grant

‘The scheme I grew up in didn’t have one gang [but two]. We used to all fight but then all started hanging out together till one of the guys from the Krew [YSG A] got jumped by the Young Team [YSG B]. After that we all started fighting again…. was good no having to worry about getting jumped in your own [scheme]…. while it lasted. But too many dodgy (dangerously unpredictable) cunts pure thinking their [hard men] and always starting [conflict].’

We see in this extract the gang organizing its form to accommodation various environments in reaction to perceived threat. The gang evolves within areas that are outside their core geographic place of domicile. YSGs ‘operate’ as occasion demands by annexing a scheme’s name, yet the members comprise individuals from elsewhere outside of the scheme and normally identify with the gang of that scheme where they live. Rehousing polices can influence this social flux whereby residents are relocated to other neighboring schemes, yet youths continue to congregate in their original scheme, or where the local scheme once stood physically. James explains:‘Our [YSG] would team up with the boys from Gangja (YSG from Seedhill) and fight the Cumbie (Gorbals based YSG) outside the dancing. Probably did that most weekends for while back…. Never had any problems way the [Ganja] boys. Only met them at the dancing. Didn’t know them from like hang about, they came from the other side of [Glasgow]. They were sound but. [They] could get a meaty squad (numbers) together, and always came to [the town center] with a lot of [gang members]. So, did we…. Helped a lot [be] cause the Gorbals could always pull a heavy team on the Saturday’s.’

As demonstrated by James, the scheme he grew up in had long been demolished and no physical territorial boundaries remained. The youths who congregated in that location where they lived continued to adopt the scheme name to signify to others the social space they felt mattered to them. Gang names do not invariably indicate either where lads live or where there is inhabitable housing. This practice suggests the associative meaning of the name itself has taken on a resonance of its own which rallies the affiliated lads.‘There was no Tuch (former name of a demolished scheme) anymore. Last of the flats on [street X] got pulled down a years back. Me and the boys that use to live there got moved all over Glasgow by the council…. [but] we still always met back up on the weekends at the shops (which remained) …. Still called ourselves Kimbo Kill Boys.’

6.2. Youth Street Gang Structure and Membership

As Dillan suggests, a YSG may be separated into two distinct bodies, of core and associate members. Studies by Davies (1998), Miller (2015), Patrick (1973), and Sillitoe (1956) as well as autobiographical accounts of criminal autobiographies (Boyle 1977; Ferris 2005; Ferris and McKay 2001, 2010; Jeffery 2003) describe Glasgow’s YSGs as typically consisting of both a criminal core and a wider grouping whereby smaller peer groups regularly attach themselves to the core body as an anchor of support and belonging. McLean (2017a) coins the former the ‘core body’ and the latter the ‘outer layer’. The key difference between core members and those of the outer layer predominantly lies in the way the groupings define their identity and crime. The core body itself is typically numerically modest, number around three to eight individuals at most, for them being criminally agentive is central to their sense of identity. As embryonic ‘career criminals’ they are more ‘ready’ to be receptive to membership of organized crime communities. Their criminality is imputed by them to forces over which their control is minimal (Boyle 1977). While reminiscing on his days as a core YSG member in Glasgow’s south side, Boab outlined how YSGs work:‘I didn’t want to, like, join a [YSG]… it just happens, know. You are just [as YSG member] because you [are raised] in [a] scheme. People from elsewhere say “that [Dillan] from [Scheme A]”. You don’t really have a choice … people just label you [as] where you’re [raised] … some boys, but, get right into it, aye. It is kind of who they are… [they] are like the [core of the] gang, basically aye. Most the troops mighty fight sometimes, but really just hang about wi’ them (the core) … [be]cause that, people, mostly the police and shit, think they are the gang as well.’—Dillan

We could muster a squad of about 40–45 bodies depending [on occasion] or who [we] were fighting. If it was local teams, then usually 20 or that but more people would come if say a [YSG] had been arranging to come through from the other end of the city for a fight…. most times I would just hang about way my [closest friends]. There was usually eight of us really (including Boab’s two siblings) …. it is unreasonable to play football way 40 boys, or get them all in your mum’s house to play the PlayStation at once (laughs).

‘I might have fought for my [YSG]. So, did a few of my [other] pals, but I also hung about with a few boys that didn’t [fight for the local YSG]. No all my mates are [YSG] members, know what I mean…. When you’re getting called a gang all the time [by law enforcement and the local community], you just end up acting like [a gang] anyways don’t you.’

6.3. Masculinity and Violence Capital

‘Fighting gave me a rep[utation] in my own scheme…. Like people my age would recognize me cause of gang fights they had heard I had been in.’

‘The police and all them, they don’t get it. Everyone is always pure saying “stop the violence” and “stop fighting, what you do that for”. They don’t get it but. It’s about being top boy, that’s all. Fuck all to do but scrap (fight)…. [Fighting] is the only fucking wi’ folk [around here] respect you…. If you can’t handle yourselves no one will respect you.’

‘Having a [penis] does not make you a man. Might make you look like one, but you earn manhood…. Guys are meant to be tough, know, you don’t act like a woman, irrational and shit. [In]stead you think things through, do what needs to be done. You protect your family…. when in school I would get into fights thinking it made me the big man. And it probably did in my mate’s eyes, but always somebody out there harder than you…. don’t learn that till it’s too late. Acting that way, being a man [through gang violence] seen me end up missing six months of my life [by being imprisoned]. I know now you can be a man…. without having to get into trouble, [but] you don’t think of that when you’re young.’

‘Suppose a just [perceive] fighting as what guys do …. if you’re a man, you’re going to get into fights ... I loved the excitement [YSG fighting] gave me, aye. You wi’ the boys (other YSG members) chasing [rival YSGs] …. Aye, you get some buzz mate…. Daft, but you feel like the big [man] after it.’—Jerry

‘[Of] course [young males in Glasgow] get into trouble. What boy doesn’t [when] growing up. Boys fight. That’s what they do. Do you get me…. Boys will be boys won’t they…. [even] if my [own son] wasn’t getting into trouble I’d probably be worried to tell you the truth.’—Shuggie

‘I’ve a few boys of my own. To be honest mate I wouldn’t want them going off the rails or nothing. [I] do expect them to act up a bit during their teen [age years] at least…. every boy has at least one fight for the scheme. Doesn’t make them bad though.’—John

7. Gang Fights and Criminality

‘One time…. [YSG A] from the other side of the Clyde tunnel came through and started going to town (fighting) with us (YSG-B). [YSG-A] had been saying over [pirate radio station] they where coming through and going do this and that, course we got heavy tooled up and waited for them, man. Even (X and Z17) were carrying blades (knives) man…. After a heavy brawl on Govan road, two of our boys ended up jumping a taxi to the other side of the tunnel, [so] when we ended up chasing them, we basically cornered them off in the tunnel and a couple of their boys got done (severely injured, possibly stabbed)…. No kidding mate, was bodies scattered everywhere after that. Their bodies mind you, not ours (laughs)’.

‘Most [of the] time we hung out was spent getting high. Use to meet up down the woods to take buckets (a method of consuming cannabis via the use of a plastic bottle) …. People would take turns in getting the [cannabis]. I use to get it [from my older brother], but they had to pay me back, know what I mean. I couldn’t be paying for it all the time. No pure rich or nothing man …. Or sometimes we would all chip in. I got it but so didn’t pay.’—(Fraz)

‘[Progressed] from there really, suppose. Was getting nine bars (a large weight of cannabis) quite a bit at the time from [my older brother]. He was giving me them. Well no giving me them. Had to pay, course, but was getting me them if I asked. On tick (credit) as well …... most my mates had left school and had jobs, so had money to get ounces, whatever, aye. I just sold them [cannabis] …. Wouldn’t say it was intentional, know, More, I could get it and they wanted it. I needed the money.’

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldridge, Judith, Robert Ralphs, and Juanjo Medina-Ariza. 2005. Street youth gangs in an English city: Social exclusion, drugs and violence. In Eurogang VIII Workshop ‘The Social Contexts of Gangs and Troublesome Youth Groups in Multi-Ethnic Europe. Onati: International Institute for the Sociology of Law. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Elijah. 1999. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence and the Moral Life of the Inner City. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Bartie, Angela. 2010. Moral panics and Glasgow gangs: Exploring the new wave of Glasgow hooliganism, 1965–1970. Contemporary British History 24: 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Trevor, and Katy Holloway. 2004. Gang membership, drugs and crime in the UK. British Journal of Criminology 44: 305–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopal, Kalwant, and Ross Deuchar. 2016. Researching Marginalized Groups. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, Jimmy. 1977. A Sense of Freedom. London: Pan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, Paul. 2005. Terrors and young teams: Youth gangs and delinquency in Edinburgh. In European Street Gangs and Troublesome Youth Group. Edited by Scott H. Decker and Frank M. Weerman. Oxford: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Anne, and Steven Muncer. 1989. Them and us: A comparison of the cultural context of American gangs and British subcultures. Deviant Behavior 10: 271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Robert. 2017. Knife crime in Scotland soars by TEN PER CENT in a year… as victims campaigner says offenders treated too leniently. The Scottish Sun, January 4. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Robert William. 1995. Masculinities, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Robert W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society 19: 829–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomber, Ross. 2006. Pusher Myths: Re-situating the Drug Dealer. London: Free Association Books. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John. 1998. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Andrew. 1998. Street gangs, crime and policing in Glasgow during the 1930s: The case of the Beehive Boys. Social History 23: 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Andrew. 2013. City of Gangs: Glasgow and the Rise of the British Gangster. London: Hodder & Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Densley, James A. 2012. The organization of London’s street gangs. Global Crime 13: 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densley, James A. 2013. How Gangs Work: An Ethnography of Youth Violence. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchar, Ross. 2009. Gangs, Marginalised Youth and Social Capital. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchar, Ross. 2013. Policing Youth Violence: Transatlantic Connections. London: Institute of Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchar, Ross, and Maria Sapouna. 2016. ‘It’s harder to go to court yourself because you don’t really know what to expect’: Reducing the negative effects of court exposure on young people—Findings from an Evaluation in Scotland. Youth Justice 16: 130–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuchar, Ross, Johanne Miller, and Mark Barrow. 2015. Breaking down barriers with the usual suspects: Findings from a research-informed intervention with police, young people and residents in the West of Scotland. Youth Justice 15: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evening Times. 2006. Glasgow Gang Map. Evening Times, February 6. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, David P., Sandra Lambert, and Donald J. West. 1998. Criminal careers of two generations of family members in the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention 7: 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, David, Darrick Joliffe, Rolf Loeber, Magda Stouthamer-Loeber, and Larry Kalb. 2001. The concentration of offenders in families and family criminality in the prediction of boy’s delinquency. Journal of Adolescence 24: 579–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, Paul. 2005. Vendetta: Turning Your Back on Crime Can Be Deadly. Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, Paul, and Reg McKay. 2001. The Ferris Conspiracy. Edinburgh: Mainstream. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, Paul, and Reg McKay. 2010. Villains: It Takes One to Know One. Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Alistair. 2013. Street habitus: Gangs, territorialism and social change in Glasgow. Journal of Youth Studies 16: 970–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Alistair. 2015. Urban Legends: Gang Identity in the Post-Industrial City. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth, Simon, and David Brotherton. 2011. Urban Disorder and Gangs: A Critique and a Warning. London: Runnymede. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth, Simon, and Tara Young. 2006. Urban Collectives: Gangs and Other Groups. Report for Operation Cruise. London: HM Government/Metropolitan Police. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth, Simon, and Tara Young. 2008. Gang talk & gang talkers: A critique. Crime, Media & Culture 4: 175–95. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Simon. 2014. The Street Casino: Survival in the Violent Street Gang. Bristol: The Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holligan, Chris. 2013. ‘The cake and custard is good!’ A qualitative study of teenage children’s’ experience of being in prison. Children and Society 29: 366–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holligan, Chris. 2014. Breaking the code of the street: Extending Elijah Anderson’s encryption of violent street governance to retaliation in Scotland. Journal of Youth Studies 18: 634–48. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13676261.2014.992312 (accessed on 12 May 2015). [CrossRef]

- Holligan, Christopher Peter, and Ross Deuchar. 2009. Territorialities in Scotland: Perceptions of young people in Scotland. Journal of Youth Studies 12: 727–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holligan, Chris, and Ross Deuchar. 2015. What does it mean to be a man? Psychosocial undercurrents in the voices of incarcerated (violent) Scottish teenage offenders. Criminology and Criminal Justice 15: 361–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, Stephen. 1981. Hooligans or Rebels: Oral History of Working Class Childhood and Youth, 1889–1939. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery, Robert. 2003. Glasgow’s Godfather: The Astonishing inside Story of Walter Norval, the City’s First Crime Boss. Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Ronnie, and Arthur McIvor. 2004. Dangerous work, hard men and broken bodies: Masculinity in the Clydeside heavy industries: 1930–1970s. Labour History Review 69: 135–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintrea, Keith, Jon Bannister, Jon Pickering, Maggie Reid, and Naofumi Suzuki. 2008. Young People and Territoriality in British Cities. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Malcolm W. 1971. Street Gangs and Street Workers. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kupers, Terry A. 2005. Toxic masculinity as a barrier to mental health treatment in prisons. Journal of Clinical Psychology 61: 713–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, Robert. 2013. The construction of ‘tough’ masculinity: Negotiation, alignment and rejection. Gender and Language 7: 369–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, David. 2008. Three Hundred Booze and Blade gangs Blighting Scotland. The Herald. March 4. Available online: https://www.pressreader.com/uk/the-herald/20080304/281517926821436 (accessed on 9 November 2015).

- Matza, David. 1964. Delinquency and Drift. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McAra, Lesley, and Susan McVie. 2007. Youth justice? The impact of system contact on patterns of desistance from offending. European Journal of Criminology 4: 315–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAra, Lesley, and Susan McVie. 2010. Youth crime and justice: Key messages from the Edinburgh study of youth transitions and crime. Criminology and Criminal Justice 10: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mceachran, John. 2003. The Murder City—Glasgow is the Western European Killing Capital. The Daily Record. November 27. Available online: https://clippednews.wordpress.com/2003/11/28/glasgow-murder-capital-of-europe/ (accessed on 30 November 2015).

- McLean, Robert. 2017a. An Evolving Gang Model in Contemporary Scotland. Deviant Behavior 39: 309–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Robert. 2017b. Glasgow’s Evolving Urban Landscape and Gang Formation. Deviant Behavior. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Robert. 2018. How Gang Narratives Stifle Gang Research. In Gang Violence: Perspectives, Influences and Gender Differences. Edited by Cliff Akiyama. Hauppauge: Nova Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- McPhee, Iain. 2013. The Intentionally Unseen: Illicit & Illegal Drug Use in Scotland. Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt, James W. 1993. Masculinities and Crime: Critique and Reconceptualization of Theory. Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Johanne. 2015. In Every Scheme There Is a Team: A Grounded Theory of How Young People Grow in and out of Gangs in Glasgow. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University West of Scotland, Hamilton, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, Terrie E. 1993. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review 100: 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, James. 1973. A Glasgow Gang Observed. London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, John. 2008. Reluctant Gangsters: The Changing Shape of Youth Crime. London: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rafanell, Irene, Robert McLean, and Lynne Poole. 2017. Emotions and hyper-masculine subjectivities: The role of affective sanctioning in Glasgow Gangs. NORMA International Journal for Masculinity Studies 12: 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. 2009. Letting Our Communities Flourish: A Strategy for Tackling Serious Organised Crime in Scotland; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2012. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2015. Scotland Serious Organised Crime Strategy Report; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Sillitoe, Percy. 1956. Cloak without Dagger. London: Pan. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher, Frederic Milton. 1927. The Gang: A Study of 1313 Gangs in Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tolson, Andrew. 1977. The Limits of Masculinity. London: Tavistock. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil, James Diego. 1988a. Group processes and street identity: Adolescent Chicano gang members. Ethos 16: 421–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigil, James Diego. 1988b. Barrio Gangs: Street Life and Identity in Southern California. Austin: University Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Violence Reduction Unit. 2011. The Violence Must Stop: Glasgow’s Community Initiative to Reduce Violence. Second Year Report. Glasgow: VRU. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Stephen M. 2002. Men and Masculinities: Key Themes and New Directions. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Knife culture has often been an assumed trait of gang activity in Glasgow, and thus consequently has been used as a way to measure gang proliferation. Yet, the perception that declines in knife violence automatically means a decline in gang formation is naive. |

| 2 | |

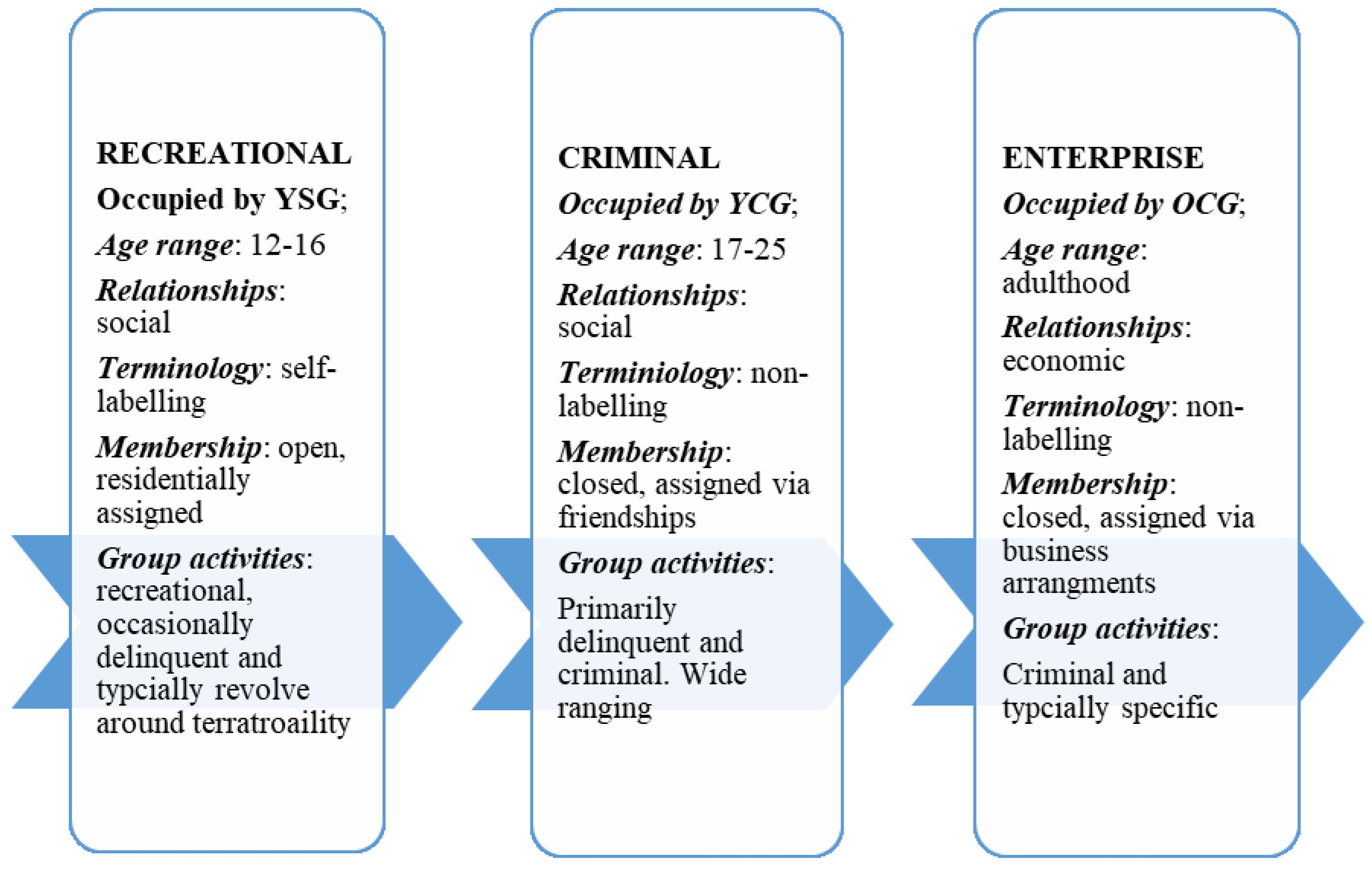

| 3 | McLean (2017a, 2017b) argues that Scotland’s academic community has explicitly focused on one form of gang typology in Scotland—Young Street Gangs—and in the process of doing so have effectively overlooked the possibility that other typologies may exist. McLean terms these other typologies as ‘Young Crime Gangs’ and ‘Serious Organized Crime Groups’. Note though, that although the latter is derived from Police Scotland’s organized crime terminology, the actual criteria required differs significantly according to McLean. |

| 4 | For example, territoriality is often assumed as inherently fixed, yet as we shall discuss in the findings this is not really the case, many youths congregate from various housing estates, and band together under one unified term (often in relation to the social space they occupy in for socialization, as opposed to residential, purposes). |

| 5 | Given Glasgow’s historical relationship with gangs, and prevalent gang culture, the city serves as an ideal reference point for studying gangs in the wider Scottish context. Likewise, given the geographical proximity (much of Scotland’s population is disproportionately located across the central belt), similarities in socioeconomic circumstances and history of heavy industry employment, it can be assumed that life in Glasgow is reflective of much of those other cities, towns, and burghs in Scotland. Yet, it is important to note, that differences between YSGs of Scotland’s West Coast and Central Belt may vary slightly with those located in the Highlands, for example, therefore it is for this reasons that the study is a comprehensive analysis of YSGs in Glasgow as opposed to being a comprehensive study of YSGs in Scotland. It would be unfair to assume life in Glasgow reflects life in all of Scotland, if not much of it. |

| 6 | Note that several additional interviewees took place after 2016, yet the data from the additional interviews were not included in McLean’s original unpublished thesis ‘Discovering Young Crime Gangs in Glasgow: Gang Organization as a Means for Gang Business’, due to time constraints to submit the thesis. |

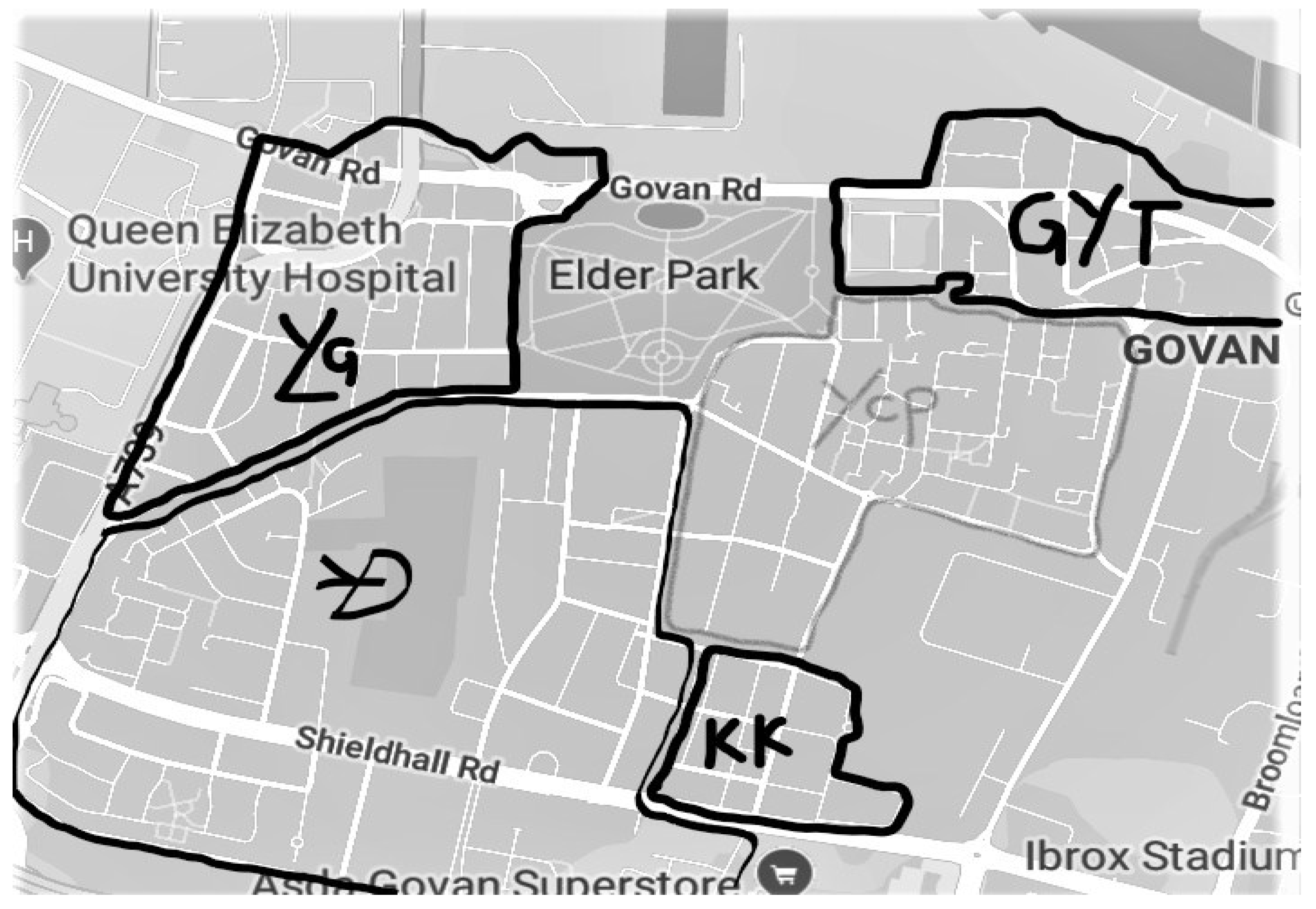

| 7 | In Glasgow, Dundee, and Aberdeen as well as in Edinburgh housing estates are usually referred to as ‘schemes’. Schemes generally follow those boundary lines which the city council defines as separating one housing estate from another, yet such lines are not a given, and are by no means fixed, as will be detailed later. The welfare state that provides this housing for typically unemployed populations in the case of Glasgow is the largest in Europe in terms of level of benefit dependency. |

| 8 | Note, that references of the ‘other’ tend to emphasise aspects that visibly distinguish outsiders such as skin color, cultural dress style, etc., In Glasgow’s YSGs, the ‘other’ is the outsider from outside of the scheme. Often schemes are particularly small and as such the youths living within them know of, or recognize most, of those who are of a similar age group. Thus when youths from elsewhere enter the scheme, they can be identified immediately as not belonging to that area. |

| 9 | From top left clockwise: YLG is Young Linty Goucho; GYT is Govan Young Team; YCP is Young Crosse Posse: KK is Kimbo Kill; YDT is Young Drumoyne Team. Source of map is Google Street Maps. |

| 10 | Please note while scheme boundaries are generally YSG boundaries, this is not always the case, and neither do gangs from these areas necessarily always carry the same name. |

| 11 | How territoriality actually presents itself is largely hidden, or at times overlooked, in contemporary gang research in Scotland. While academics tend to demonstrate territoriality as existing as a theoretical concept with invisible boundaries, law enforcement may focus on particular areas of public space where youths from a local scheme congregate (See Fraser 2013; Violence Reduction Unit 2011). |

| 12 | Most YSGs core body tended to be closer to numbering between 3–5 individuals, and the outer layer between 20–30. |

| 13 | The Bundy no longer exists as it has since been demolished. It once stood where Silverbrun shopping center is situated. Although obtaining a notorious reputation, it was relatively small in size when compared to surrounding territories and consisted of a block of post-war three story tenements, a block of two story flats, and several four-in-a-block cottage homes. |

| 14 | Note, while the source given also identifies ‘Tuecharhill Young Team’, this is another name for the ‘Kimbo Kill’. |

| 15 | It was also found that gang photos placed on social media, typically consisted of core YSG members and nonmembers alike, who for the purpose of the photograph alone adopt gang-like behavior, status, and insignia. |

| 16 | Despite a considerable proportion of the sample having found themselves suffering from second- or even third-generational unemployment, manual types of work were nonetheless deemed crucial assets in being able to self-legitimize one’s manliness (Johnston and McIvor 2004). However, the desire to express masculinity through work-related activities has become somewhat hindered and constrained, due to globalized processes which have resulted in Glasgow’s deindustrialization. Thus, being young and lacking legitimate outlets for masculine expression, participants spoke of channelling masculinity through aggressive recreational outlets, of which YSG formation may be one. |

| 17 | X and Z are non-gang members who often associated with these particular YSG but rarely got involved in YSG fights. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McLean, R.; Holligan, C. The Semiotics of the Evolving Gang Masculinity and Glasgow. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080125

McLean R, Holligan C. The Semiotics of the Evolving Gang Masculinity and Glasgow. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(8):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080125

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcLean, Robert, and Chris Holligan. 2018. "The Semiotics of the Evolving Gang Masculinity and Glasgow" Social Sciences 7, no. 8: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080125

APA StyleMcLean, R., & Holligan, C. (2018). The Semiotics of the Evolving Gang Masculinity and Glasgow. Social Sciences, 7(8), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080125