The Relationships of School-Based Discrimination and Ethnic-Racial Socialization to African American Adolescents’ Achievement Outcomes

Abstract

1. Conceptual Underpinnings

2. School-Based Racial Discrimination

3. Ethnic-Racial Socialization

4. The Present Study

5. Method

5.1. Sample

5.2. Measures

5.2.1. Predictor Variables

5.2.2. Outcome Variables

6. Procedure

7. Data Analysis Plan

8. Results

8.1. Preliminary Analysis

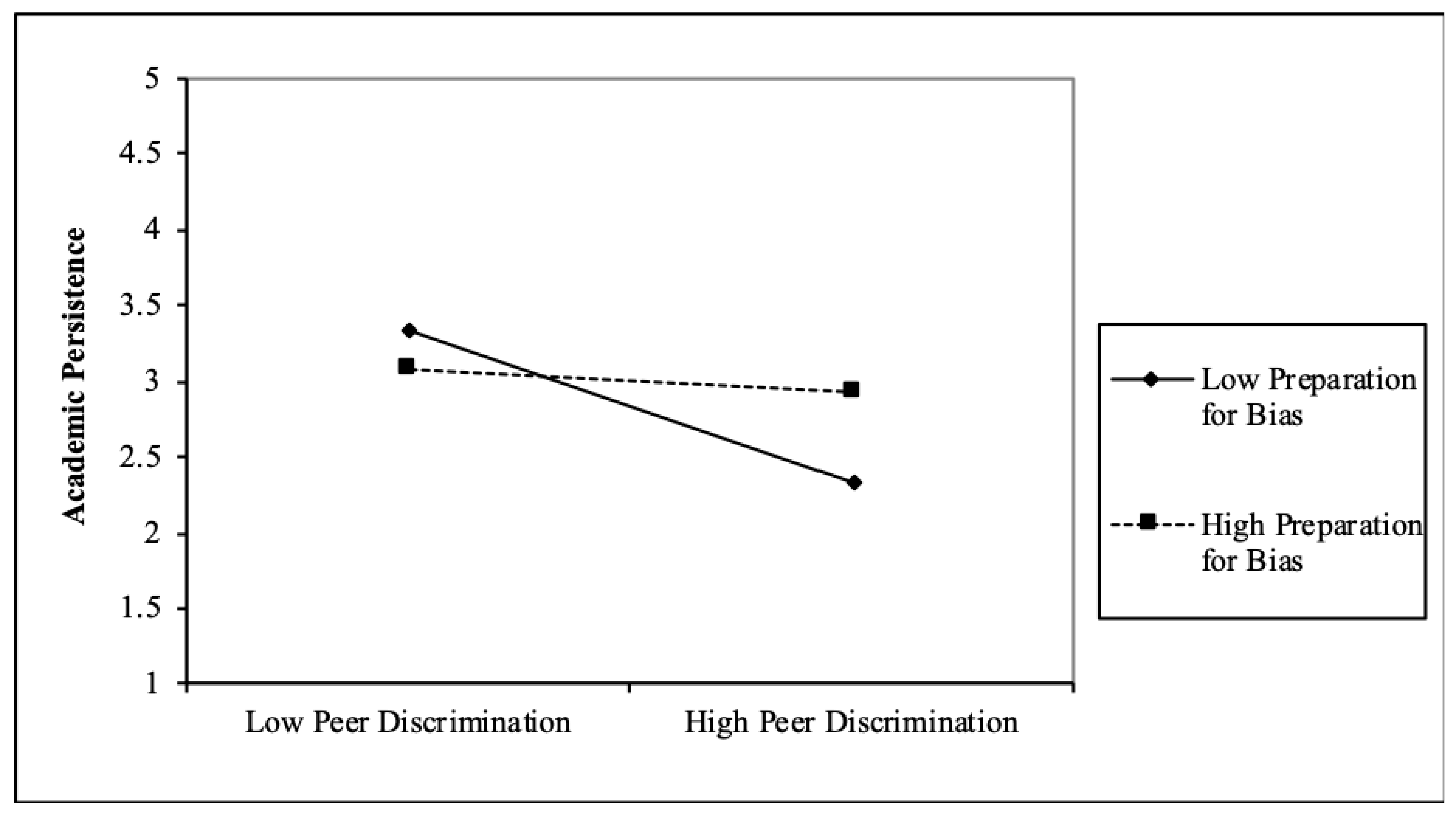

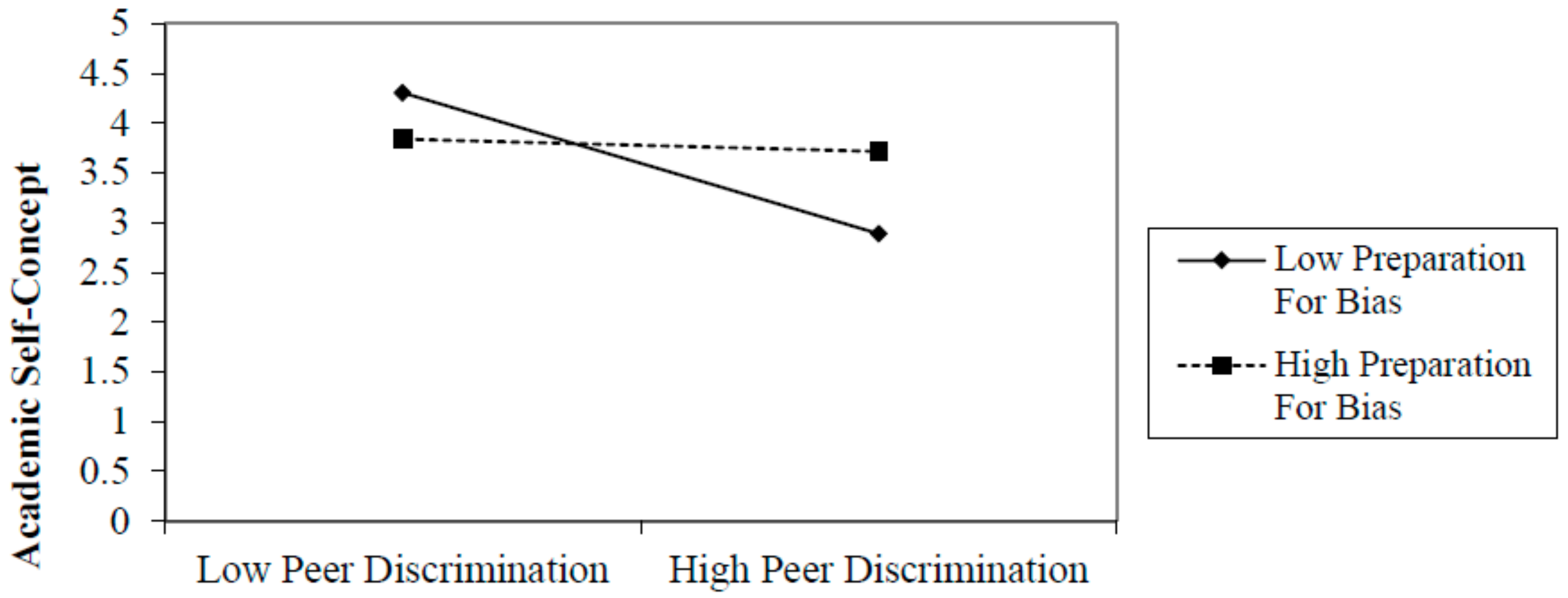

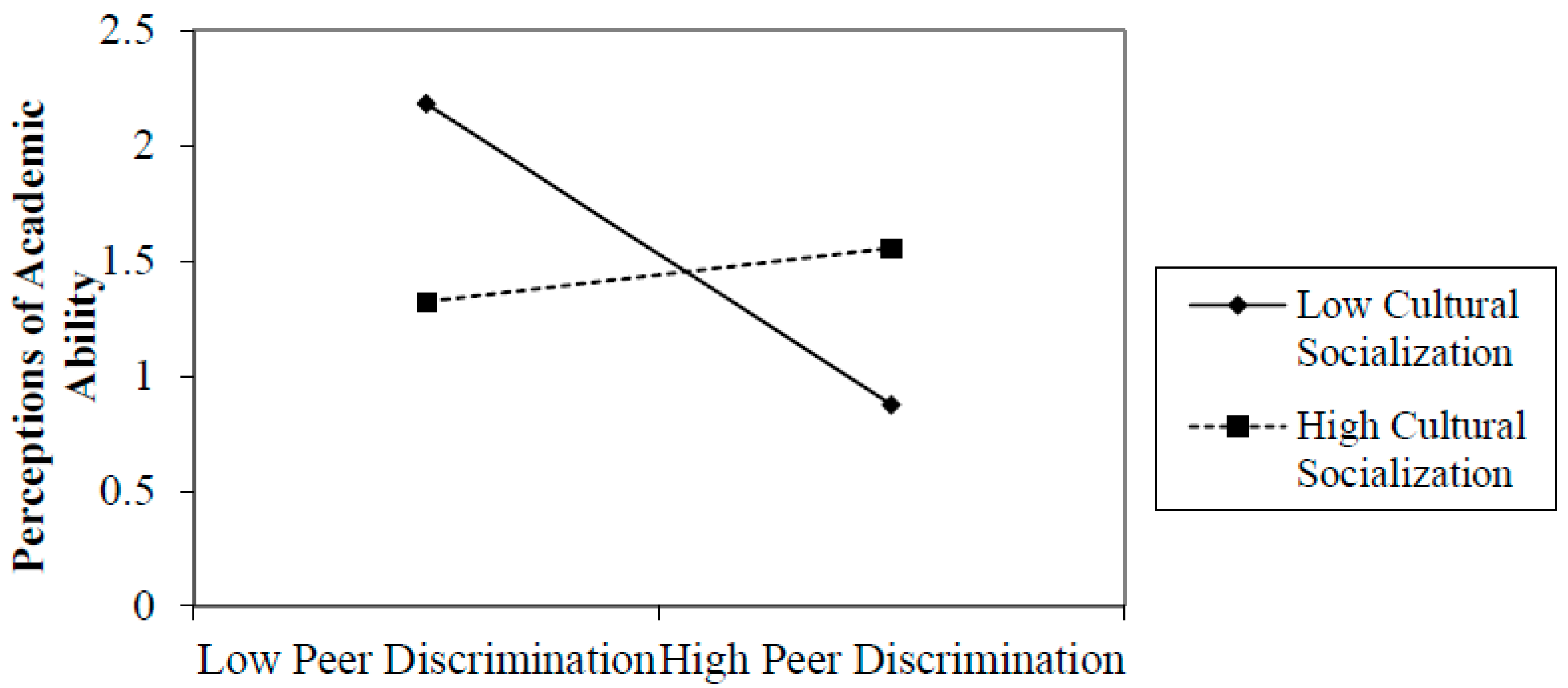

8.2. Hierarchical Regressions

9. Discussion

10. Limitations and Future Directions

11. Implications

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Teacher Discrimination Items

- Teachers call on you less often than they call on other kids because you are Black?

- Teachers grade you harder than they grade other kids because you are Black?

- You get disciplined more harshly by teachers than other kids do because you are Black?

- Teachers think you are less smart than you really are because you are Black?

- How stressful is it for you when teachers at your school treat you in these ways?

Appendix B. Peer Discrimination Items

- At school, how often do you feel like you are not picked for certain teams or other school activities because you are Black?

- At school, how often do you feel that you get in fights with some kids because you are Black?

- At school, how often do you feel that kids do not want to hang out with you because you are Black?

- How stressful is it for you when other kids at school treat you in these ways?

References

- Bellmore, Amy, Adrienne Nishina, Ji-in You, and Ting-Lan Ma. 2012. School context protective factors against peer ethnic discrimination across the high school years. American Journal of Community Psychology 49: 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, Aprile D., and Sandra Graham. 2013. The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: Does the source of Discrimination matter? Developmental Psychology 49: 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, Catherine P., Anne L. Sawyer, and Lindsey M. O’Brennan. 2007. Bullying and peer victimization at school: Perceptual differences between students and school staff. School Psychology Review 36: 361–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, Mia Smith, Thomaseo Burton, and Candace Best. 2007. Racism experiences and psychological functioning in African American college freshmen: Is racial socialization a buffer? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 13: 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, Christy M. 2015. Associations of intergroup interactions and school racial socialization with academic motivation. Journal of Educational Research 108: 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, Christy M., and Dorinda J. Carter Andrews. 2016. Variations in students’ perceived reasons for, sources of, and forms of in-school discrimination: A latent class analysis. Journal of School Psychology 57: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, Christy M., and Tabbye Chavous. 2011. Racial identity, school racial climate, and school intrinsic motivation among African American youth: The importance of person-context congruence. Journal of Research and Adolescence 21: 849–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavous, Tabbye M., Deborah Rivas-Drake, Ciara Smalls, Tiffany Griffin, and Courtney Cogburn. 2008. Gender matters too: The influences of school racial discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement outcomes among African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology 44: 637–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogburn, Courtney D., Tabbye M. Chavous, and Tiffany M. Griffin. 2011. School-based racial and gender discrimination among African American adolescents: Exploring gender variation in frequency and implications for adjustment. Race and Social Problems 3: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Patricia, Stephen G. West, and Leona S. Aiken. 2003. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, Edward L., Robert J. Vallerand, Luc G. Pelletier, and Richard M. Ryan. 1991. Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist 26: 325–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNavas-Walt, Carmen, Bernadette D. Proctor, and Jessica C. Smith. 2010. U.S. Census Bureau, Current population reports, P60–239. In Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2010; Washington: U.S Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Dotterer, Aryn M., Susan M. McHale, and Ann C. Crouter. 2009. Sociocultural factors and school engagement among African American youth: The roles of racial discrimination, racial socialization, and ethnic identity. Applied Developmental Science 13: 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergus, Stevenson, and Marc A. Zimmerman. 2005. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health 26: 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, Ann R., and Christina M. Shaw. 1999. African Americans’ mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: The moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology 46: 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Celia B., Scyatta A. Wallace, and Rose E. Fenton. 2000. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 29: 679–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, Patricia A., Andrew P. Tix, and Kenneth E. Barron. 2004. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology 51: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Sandra, and Jaana Juvonen. 2002. Ethnicity, peer harassment, and adjustment in middle school: An exploratory study. The Journal of Early Adolescence 22: 173–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Melissa L., Niobe Way, and Kerstin Pahl. 2006. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology 42: 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris-Britt, April, Cecelia R. Valrie, Beth Kurtz-Costes, and Stephanie J. Rowley. 2007. Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence 17: 669–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoover-Dempsey, Kathleen V., and Howard M. Sandler. 2005. Final Performance Report for OERI Grant # R305T010673: The Social Context of Parental Involvement: A Path to Enhanced Achievement; Washington: Project Monitor, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Hughes, Diane, and Lisa Chen. 1997. When and what parents tell their children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Applied Developmental Science 1: 200–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Diane, and Deborah Johnson. 2001. Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family 63: 981–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Diane, James Rodriguez, Emilie P. Smith, Deborah J. Johnson, Howard C. Stevenson, and Paul Spicer. 2006. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions of future study. Developmental Psychology 42: 747–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado, Sylvia, and Deborah Faye Carter. 1997. Effects of college transition and perceptions of the campus racial climate on Latino college students’ sense of belonging. Sociology of Education 70: 324–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corporation. 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24. Armonk: IBM Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Lesane-Brown, Chase L. 2006. A review of race socialization within Black families. Developmental Review 26: 400–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, Maria. 2010. Perceived discrimination and linguistic adaptation of adolescent children of immigrants. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39: 940–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neblett, Enrique W., Jr., Cheri L. Philip, Courtney D. Cogburn, and Robert M. Sellers. 2006. African American adolescents’ discrimination experiences and academic achievement: Racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black Psychology 32: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, John G. 1979. Development of perception of own attainment and causal attributions for success and failure in reading. Journal of Educational Psychology 71: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, Erika Y., Niobe Way, and Diane L. Hughes. 2014. Trajectories of ethnic-racial discrimination among ethnically diverse early adolescents: Associations with psychological and social adjustment. Child Development 85: 2339–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, Marie F. 2002. Racial socialization of young Black children. In Black Children: Social Educational and Parental Environments, 2nd ed. Edited by Harriette P. McAdoo. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., Patrick J. Curran, and Daniel J. Bauer. 2006. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 31: 437–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProximityOne. 2010. Michigan School District Demographic Files. Available online: http://proximityone.com/mi_sdc.htm (accessed on 29 September 2014).

- Romero, Andrea J., and Robert E. Roberts. 1998. Perception of discrimination and ethnocultural variables in a diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 21: 641–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, Chad Allen, Dorothy Lynn Espelage, and Lisa E. Monda-Amaya. 2009. Bullying and victimisation rates among students in general and special education: A comparative analysis. Educational Psychology 29: 761–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, Susan Rakosi, and Niobe Way. 2004. Experiences of discrimination among African American, Asian American and Latino adolescents in an urban high school. Youth and Society 35: 420–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, S. J. 2004. Academic preparedness scales. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, Mavis G. 1997. Overcoming obstacles: Academic achievement as a response to racism and discrimination. Journal of Negro Education 66: 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., Cleopatra H. Caldwell, Robert M. Sellers, and James S. Jackson. 2008. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology 44: 1288–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, Margaret Beale. 1995. Old issues and new theorizing abut African American youth: A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory. In Black Youth: Perspectives on Their Status in the United States. Edited by Ronald L. Taylor. Westport: CT Praeger, pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Margaret Beale. 1999. Social and cultural influences on school adjustment: The application of identity-focused cultural ecological perspective. Educational Psychologist 34: 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Margaret Beale, Davido Dupree, and Tracey Hartmann. 1997. A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology 9: 817–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, Margaret Beale, Davido Dupree, Michael Cunningham, Vinay Harpalani, and Michèle Muñoz-Miller. 2003. Vulnerability to violence: A contextually-sensitive developmental perspective on African American adolescents. Journal of Social Issues 59: 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suizzo, Marie-Anne, Courtney Robinson, and Erin Pahlke. 2008. African American mothers’ socialization beliefs and goals with young children: Themes of history, education, and collective independence. Journal of Family Issues 29: 287–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatum, Beverly Daniel. 1997. Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Ming-Te, and James P. Huguley. 2012. Parental racial socialization as a moderator of the effects of racial discrimination on educational success among African American adolescents. Child Development 83: 1716–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellborn, James G. 1991. Engaged and Disaffected Action: The Conceptualization and Measurement of Motivation in the Academic Domain. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- White-Johnson, Rhonda L., Kahlil R. Ford, and Robert M. Sellers. 2010. Parental racial socialization profiles: Association with demographic factors, racial discrimination, childhood socialization, and racial identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 16: 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Carol A., Jacquelynne S. Eccles, and Arnold Sameroff. 2003. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality 71: 1197–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Mean | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Parental Education (PR) | ----- | 7.31 | 1.87 | ||||||||

| 2. | Peer Discrimination | −0.15 | ----- | 1.73 | 0.93 | |||||||

| 3. | Teacher Discrimination | −0.11 | 0.66 ** | ------ | 1.75 | 0.93 | ||||||

| 4. | Preparation for Bias | 0.08 | 0.37 ** | 0.32 ** | ------ | 2.96 | 1.17 | |||||

| 5. | Cultural Socialization | 0.12 † | 0.24 * | 0.30 ** | 0.75 ** | ----- | 2.22 | 1.17 | ||||

| 6. | Academic Persistence | 0.28 * | 0.28 * | −0.20 † | −0.06 | 0.04 | ----- | 3.47 | 0.49 | |||

| 7. | Academic Self-Concept | 0.25 * | 0.25 * | −0.15 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.54 ** | ----- | 5.10 | 0.86 | ||

| 8. | Academic Self-Efficacy | 0.20 † | 0.20 † | −0.17 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.61 ** | 0.64 ** | ----- | 3.20 | 0.51 | |

| 9. | Parent-reported Academic Ability | 0.38 ** | −0.24 * | −0.21 † | −0.14 | −0.25 * | 0.39 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.28 * | ----- | 4.94 | 1.23 |

| 10. | Parent-reported Academic Preparedness | 0.32 ** | −0.28 * | −0.26 * | −0.21 † | −0.22 † | 0.23 † | 0.49 ** | 0.26 * | 0.77 * | 3.62 | 0.91 |

| Variable | Academic Persistence | Academic Self-Concept | Academic Self-Efficacy | Parent-Reported Academic Ability | Parent-Reported Academic Preparedness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | |

| Step 1 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.02 | (0.11) | 0.02 | 0.45 (0.18) | 0.28 * | −0.02 (0.12) | −0.02 | 1.12 (0.24) | 0.46 ** | 0.76 (0.19) | 0.42 ** |

| Parent Education (PR) | 0.07 | (0.03) | 0.28 * | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.30 ** | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.21 | 0.28 (0.06) | 0.42 ** | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.34 ** |

| Total R2 | 0.08 † | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | 0.36 ** | 0.28 ** | ||||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.01 | (0.11) | 0.01 | 0.45 (0.19) | 0.27 * | −0.02 (0.12) | −0.02 | 1.11 (0.23) | 0.46 ** | 0.77 (0.18) | 0.43 ** |

| Parent Education (PR) | 0.06 | (0.03) | 0.22 * | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.28 * | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.21 | 0.25 (0.06) | 0.41 ** | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.33 ** |

| Peer Discrimination | −0.14 | (0.06) | −0.30 * | −0.10 (0.10) | −0.12 | −0.00 (0.09) | −0.00 | −0.12 (0.13) | −0.10 | −0.16 (0.10) | −0.17 |

| Preparation for Bias | 0.01 | (0.06) | 0.02 | −0.03 (0.10) | −0.03 | −0.01 (0.07) | −0.02 | −0.27 (0.13) | −0.22 * | −0.17 (0.10) | −0.19 |

| R2 | 0.08* | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 * | 0.08 * | ||||||

| Total R2 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.36 | ||||||

| Step 3 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.06 | (0.10) | 0.06 | 0.52 (0.18) | 0.32 ** | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.03 | 1.15 (0.23) | 0.47 ** | 0.75 (0.18) | 0.42 ** |

| Parent Education (PR) | 0.03 | (0.03) | 0.13 | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.19 | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.11 | 0.25 (0.07) | 0.38 ** | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.35 ** |

| Peer Discrimination | −0.29 | (0.08) | −0.60 ** | −0.32 (0.13) | −0.39 * | −0.14 (0.09) | −0.28 | −0.25 (0.17) | −0.20 * | −0.10 (0.13) | 0.10 |

| Preparation for Bias | 0.09 | (0.06) | 0.18 | 0.09 (0.12) | 0.12 | 0.06 (0.07) | 0.12 | −0.20 (0.14) | −0.16 | −0.21(0.11) | −0.22 |

| Peer Discrimination X | 0.21 | (0.07) | 0.42 ** | 0.32 (0.13) | 0.38 * | 0.21 (0.08) | 0.39 * | 0.21 (0.17) | 0.15 | 0.09 (0.14) | −0.09 |

| Preparation for Bias | |||||||||||

| R2 | 0.10 | ** | 0.07 * | 0.08 * | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||||

| Total R2 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.37 | ||||||

| Variable | Academic Persistence | Academic Self-Concept | Academic Self-Efficacy | Parent-Reported Academic Ability | Parent-Reported Academic Preparedness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | ||

| Step 1 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.01 | (0.11) | 0.01 | 0.43 (0.19) | 0.26 * | −0.01 (0.12) | −0.01 | 1.11 (0.25) | 0.45 ** | 0.75 (0.19) | 0.42 ** |

| Parent Education (PR) | 0.07 | (0.03) | 0.78 * | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.30 * | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.21 † | 0.27 (0.07) | 0.42 ** | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.35 ** |

| Total R2 | 0.08 † | 0.14 ** | 0.05 | 0.35 ** | 0.27 ** | ||||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.01 | (0.11) | 0.01 | 0.42 (0.19) | 0.26 * | −0.01 (0.13) | −0.01 | 1.12 (0.19) | 0.42 ** | 0.76 (0.19) | 0.42 ** |

| Parent Education (PR) | 0.06 | (0.03) | 0.22 † | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.27 * | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.23 | 0.26 (0.05) | 0.33 ** | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.33 ** |

| Peer Discrimination | −0.15 (0.06) | −0.30 † | −0.11 (0.10) | −0.13 | −0.01 (0.08) | −0.01 | −0.20 (0.10) | −0.21 † | −0.19 (0.10) | −0.21 † | |

| Cultural Socialization | 0.03 | (0.06) | 0.06 | 0.02 (0.10) | 0.02 | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.08 | −0.10 (0.10) | −0.11 | −0.10 (0.10) | −0.11 |

| R2 | 0.08 † | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.07 * | ||||||

| Total R2 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.34 | ||||||

| Step 3 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.08 | (0.11) | 0.09 | 0.54 (0.18) | 0.33 ** | 0.05 (0.12) | 0.05 | 1.26 (0.23) | 0.51 ** | 0.76 (0.19) | 0.42 ** |

| Parent Education | 0.03 | (0.03) | 0.11 | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.16 | 0.04(0.03) | 0.14 | 0.21 (0.07) | 0.07 ** | 0.16(0.05) | 0.33 ** |

| Peer Discrimination | −0.19 (0.06) | −0.40 * | −0.18 (0.10) | −0.22 † | −0.03(0.07) | −0.07 | −0.27(0.12) | −0.22 * | −0.19(0.10) | −0.21 † | |

| Cultural Socialization | 0.04 (0.06) | 0.08 | 0.04 (0.09) | 0.04 | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.06 | −0.04 (0.12) | 0.03 | −0.11 (0.10) | −0.11 | |

| Peer Discrimination X | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.36 ** | 0.27 (0.09) | 0.35 ** | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.28 * | 0.38 (0.13) | 0.30 ** | −0.02(0.11) | −0.02 | |

| Cultural Socialization | |||||||||||

| R2 | 0.11 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.07 * | 0.05 ** | 0.00 | ||||||

| Total R2 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.46 | 0.34 | ||||||

| Variable | Academic Persistence | Academic Self-Concept | Academic Self-Efficacy | Parent-Reported Academic Ability | Parent-Reported Academic Preparedness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | ||

| Step 1 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.02 | (0.12) | 0.02 | 0.45 (0.18) | 0.28 * | 0.45 (0.12) | −0.02 | 1.12 (0.24) | 0.46 ** | 0.76 (0.19) | 0.42 ** |

| Parent Education | 0.07 | (0.03) | 0.28 * | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.30 ** | 0.13 (0.03) | 0.21 † | 0.28 (0.06) | 0.42 ** | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.05 ** |

| Total R2 | 0.08 | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | 0.36 ** | 0.28 ** | ||||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.01 | (0.11) | 0.01 | 0.42 (0.19) | 0.26 * | 0.42(0.19) | 0.26 * | 1.11 (0.23) | 0.45 ** | 0.75 (0.18) | 0.42 ** |

| Parent Education | 0.07 | (0.03) | 0.26 ** | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.29 * | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.29 * | 0.28 (0.06) | 0.42 ** | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.34 ** |

| Teacher Disc. | −0.07 (0.07) | −0.16 | −0.07 (0.10) | −0.09 | −0.07 (0.10) | −0.09 | −0.08 (0.13) | −0.07 | −0.13 (0.10) | −0.14 | |

| Preparation for Bias | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.04 | −0.03 (0.10) | −0.04 | −0.03 (0.10) | −0.04 | −0.29 (0.12) | −0.23 * | −0.19 (0.10) | −0.20 † | |

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 * | 0.08 * | ||||||

| Total R2 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.36 | ||||||

| Step 3 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.03 | 0.51 (0.19) | 0.31 ** | 0.51 (0.19) | 0.31 ** | 1.16 (0.24) | 0.47 ** | 0.73 (0.19) | 0.41 ** | |

| Parent Education | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.24 * | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.26 * | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.26 * | 0.27 (0.06) | 0.40 ** | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.35 ** | |

| Teacher Disc. | 0.11 (0.07) | −0.22 | −0.16 (0.11) | 0.20 | −0.16 (0.11) | −0.20 | −0.15 (0.14) | 0.12 | −0.10 (0.11) | −0.10 | |

| Preparation for Bias | 0.00 (0.06) | −0.01 | 0.01 (0.10) | 0.01 | 0.01 (0.10) | 0.01 | −0.25 (0.13) | −0.20 † | −0.21 (0.10) | −0.22 | |

| Teacher Disc. X | 0.06 (0.07) | 0.13 | 0.18 (0.11) | 0.21 † | 0.18 (0.11) | 0.21 † | 0.16 (0.14) | 0.12 | −0.07 (0.11) | −0.07 | |

| Preparation for Bias | |||||||||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.04 † | 0.04 † | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Total R2 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.44 | 0.36 | ||||||

| Variable | Academic Persistence | Academic Self-Concept | Academic Self-Efficacy | Parent-Reported Academic Ability | Parent-Reported Academic Preparedness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | ||

| Step 1 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.01 | (0.11) | 0.01 | 0.43 (0.19) | 0.26 * | 0.43 (0.19) | 0.26 * | 1.11 (0.25) | 0.45 ** | 0.75 (0.19) | 0.42 ** |

| Parent Education | 0.07 | (0.03) | 0.28 * | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.30 * | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.30 * | 0.27 (0.07) | 0.42 ** | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.35 ** |

| Total R2 | 0.08 † | 0.14 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.27 ** | ||||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||||

| Gender | −0.01 (0.11) | −0.01 | 0.40 (0.19) | 0.25 | 0.40 (0.19) | 0.25 * | 1.09 (0.24) | 0.45 ** | 0.73 (0.19) | 0.40 ** | |

| Parent Education | 0.06 | (0.03) | 0.24 † | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.27 * | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.27 * | 0.27 (0.07) | 0.41 ** | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.33 ** |

| Teacher Disc. | −0.10 (0.06) | −0.21 † | −0.13 (0.10) | −0.16 | −0.13 (0.10) | −0.16 | −0.17 (0.14) | −0.13 | −0.19 (0.10) | −0.20 | |

| Cultural Socialization | 0.02 | (0.06) | 0.04 | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.04 | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.04 | −0.10 (0.13) | −0.08 | −0.09 (0.10) | −0.10 |

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 † | ||||||

| Total R2 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.33 | ||||||

| Step 3 | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.02 | (0.11) | 0.02 | 0.48 (0.18) | 0.29 * | 0.48 (0.18) | 0.29 | 1.17 (0.24) | 0.48 ** | 0.72 (0.19) | 0.40 ** |

| Parent Education | 0.05 | (0.03) | 0.19 | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.19 | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.19 | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.35 ** | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.33 ** |

| Teacher Disc. | −0.13 (0.06) | −0.27 * | −0.20 (0.10) | −0.24 † | −0.20 (0.10) | −0.24 † | −0.24 (0.13) | −0.19 | −0.19 (0.11) | −0.20 † | |

| Cultural Socialization | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.04 | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.04 | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.04 | −0.08 (0.13) | −0.06 | −0.09 (0.10) | −0.10 | |

| Teacher Disc. X | 0.09 (0.06) | 0.20 | 0.21 (0.09) | 0.29 * | 0.21 (0.09) | 0.29 * | 0.29 (0.12) | 0.24 * | −0.01 (0.10) | −0.01 | |

| Cultural Socialization | |||||||||||

| R2 | 0.14 | 0.07 * | 0.07 * | 0.05 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Total R2 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.43 * | 0.33 | ||||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banerjee, M.; Byrd, C.; Rowley, S. The Relationships of School-Based Discrimination and Ethnic-Racial Socialization to African American Adolescents’ Achievement Outcomes. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100208

Banerjee M, Byrd C, Rowley S. The Relationships of School-Based Discrimination and Ethnic-Racial Socialization to African American Adolescents’ Achievement Outcomes. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(10):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100208

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanerjee, Meeta, Christy Byrd, and Stephanie Rowley. 2018. "The Relationships of School-Based Discrimination and Ethnic-Racial Socialization to African American Adolescents’ Achievement Outcomes" Social Sciences 7, no. 10: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100208

APA StyleBanerjee, M., Byrd, C., & Rowley, S. (2018). The Relationships of School-Based Discrimination and Ethnic-Racial Socialization to African American Adolescents’ Achievement Outcomes. Social Sciences, 7(10), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100208