Ascription, Achievement, and Perceived Equity of Educational Regimes: An Empirical Investigation

Abstract

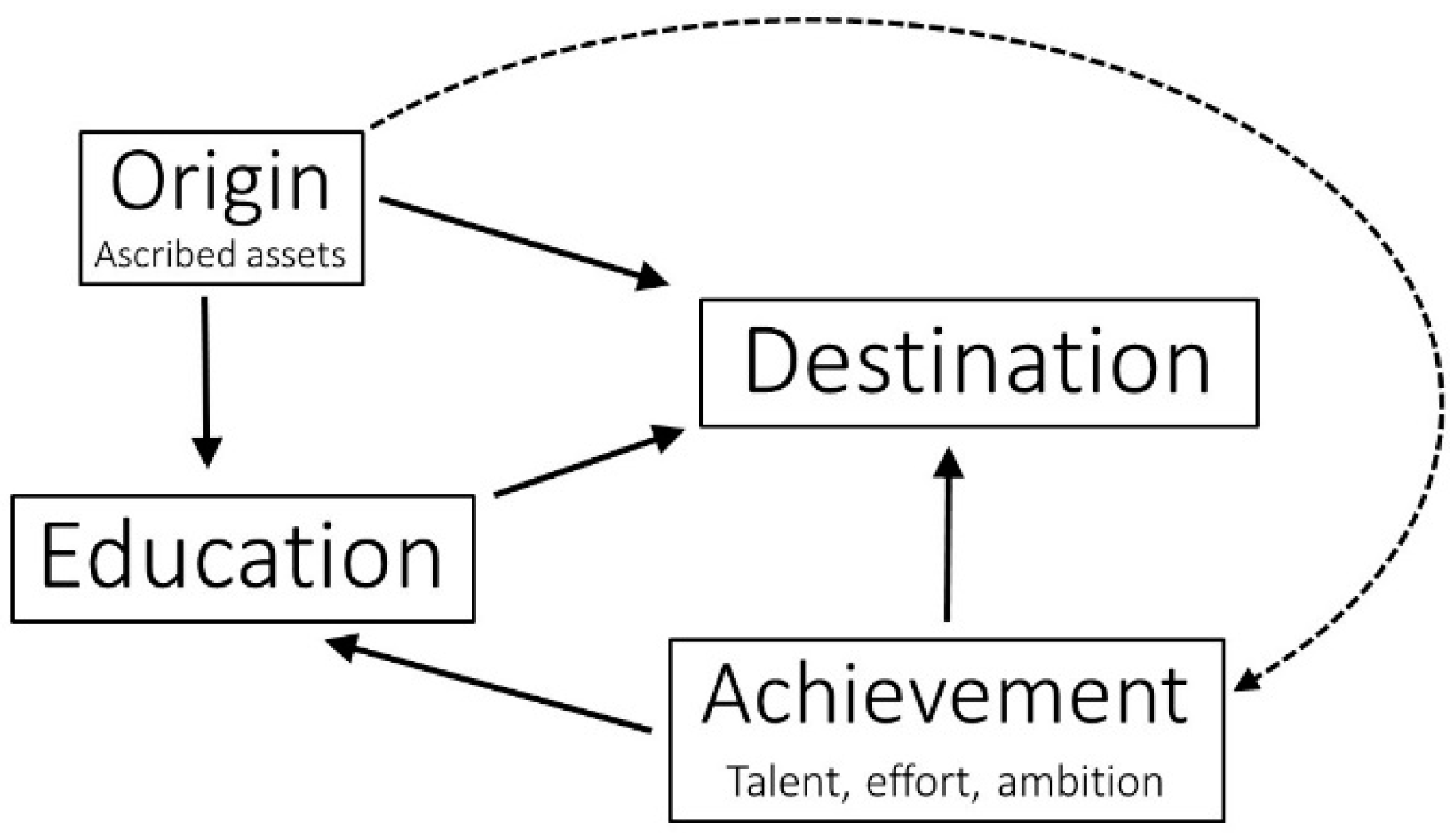

:1. What Determines Success: Social Background or Individual Achievement?

2. Educational Regimes

2.1. Skill Specificity and Stratification

2.2. Adding a Labour Market Perspective

2.3. Education and Power Relations

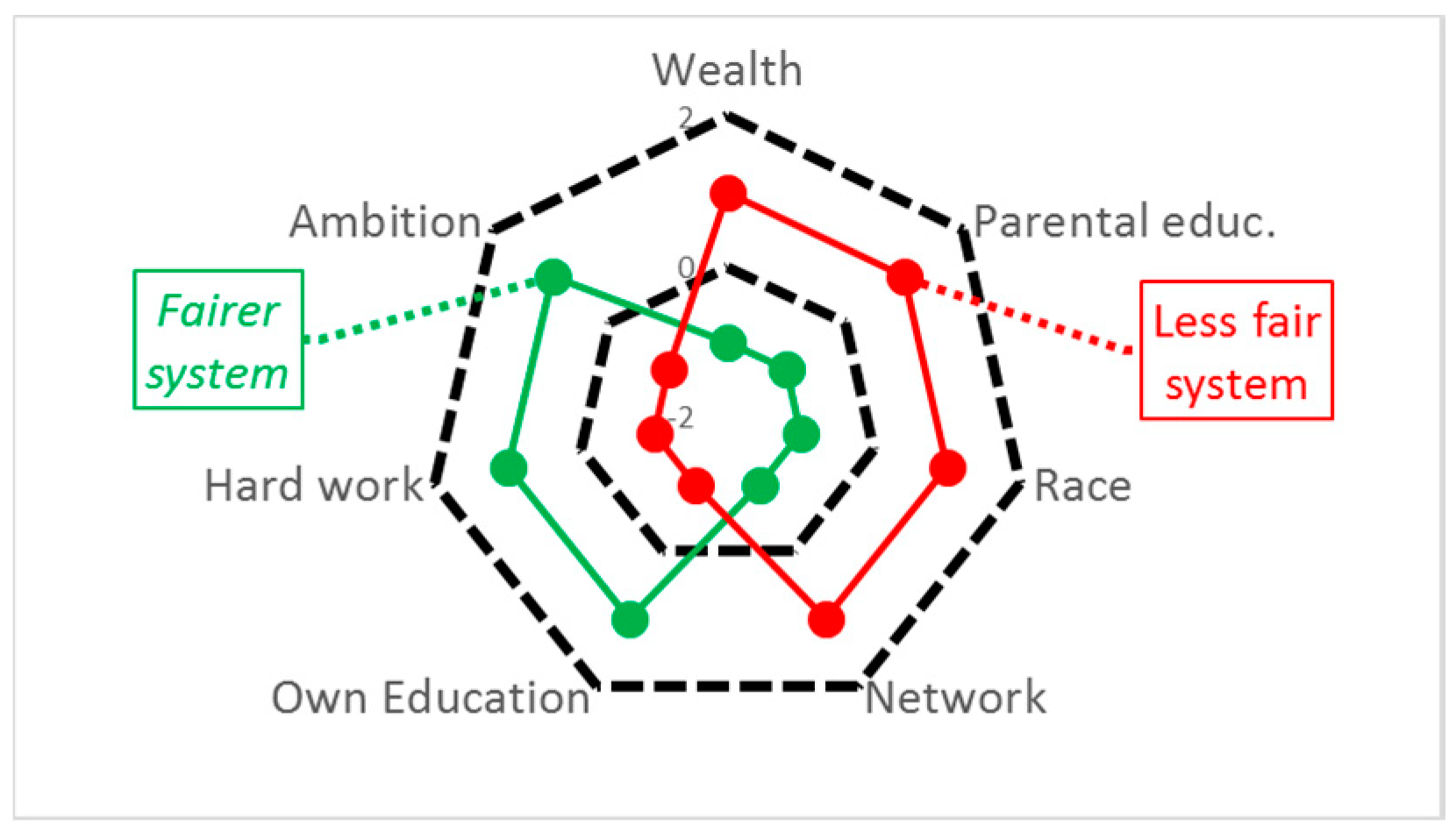

3. Cross-National Differences in Educational and Social Fairness

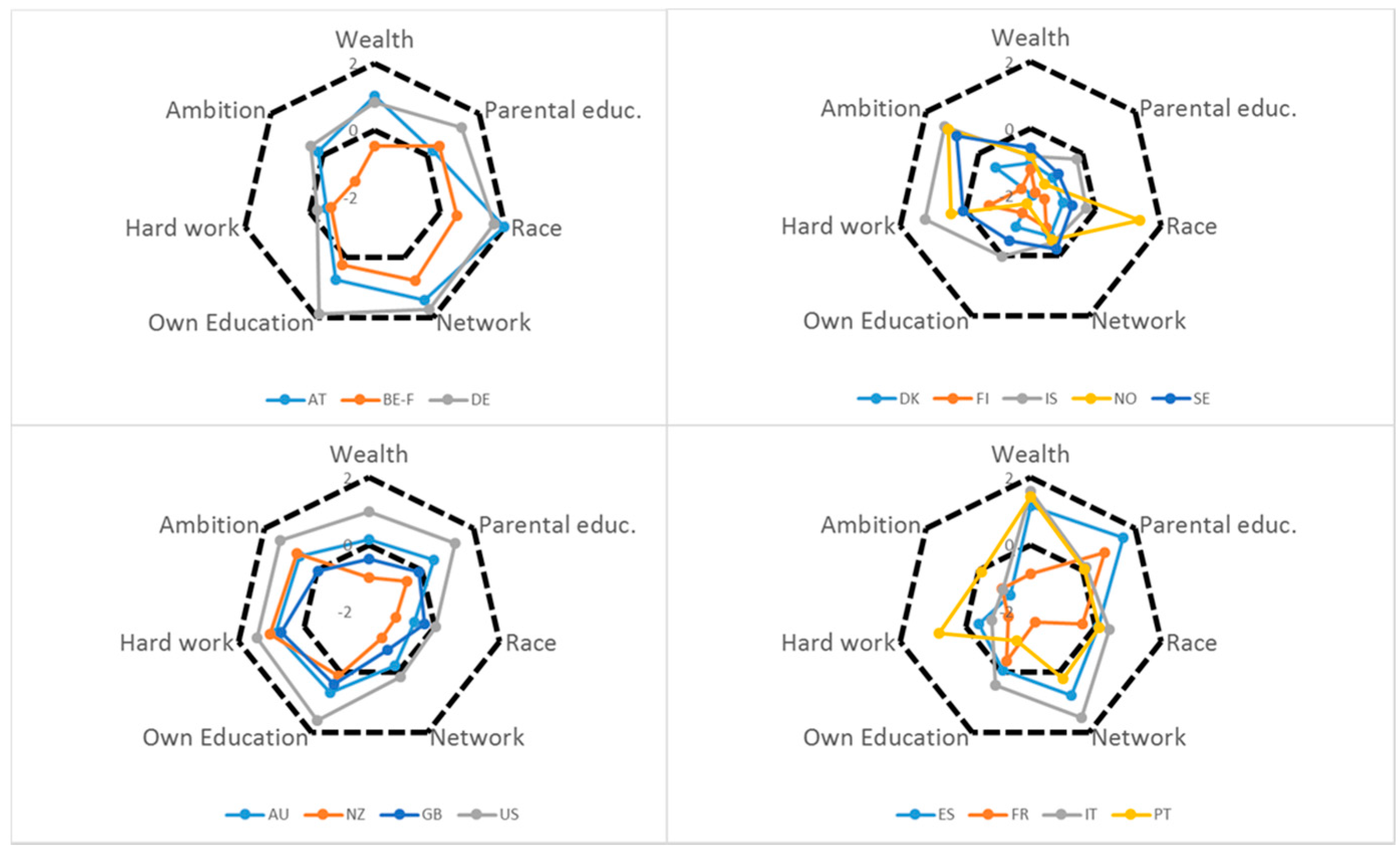

3.1. Continental Countries

3.2. Anglo-Saxon Countries

3.3. Mediterranean Countries

3.4. Nordic Countries

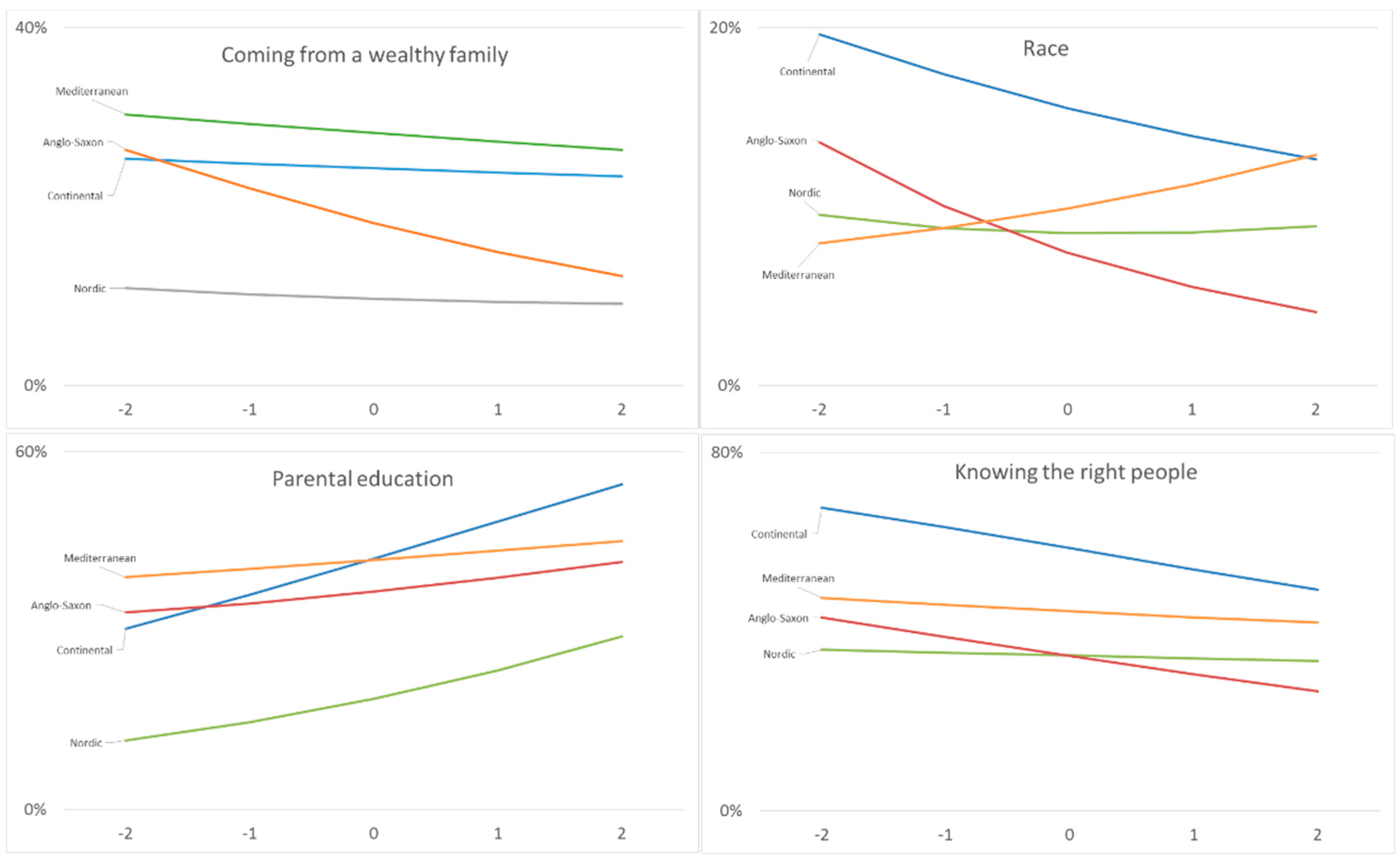

3.5. Relationship with Individual Educational Background

4. Data and Method

5. Results

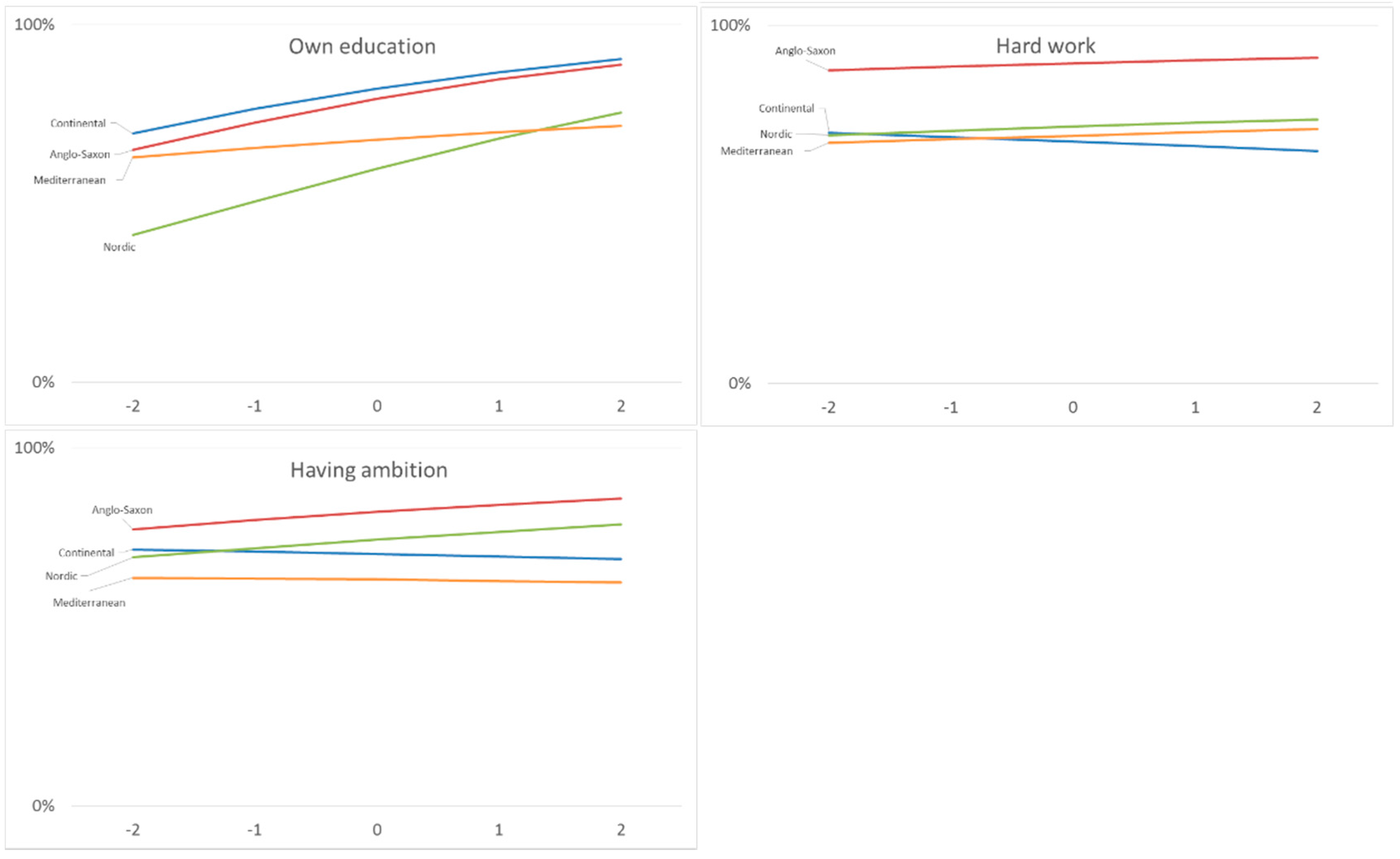

5.1. Getting ahead in Life

5.1.1. Country Averages

5.1.2. Relationship with Educational Background

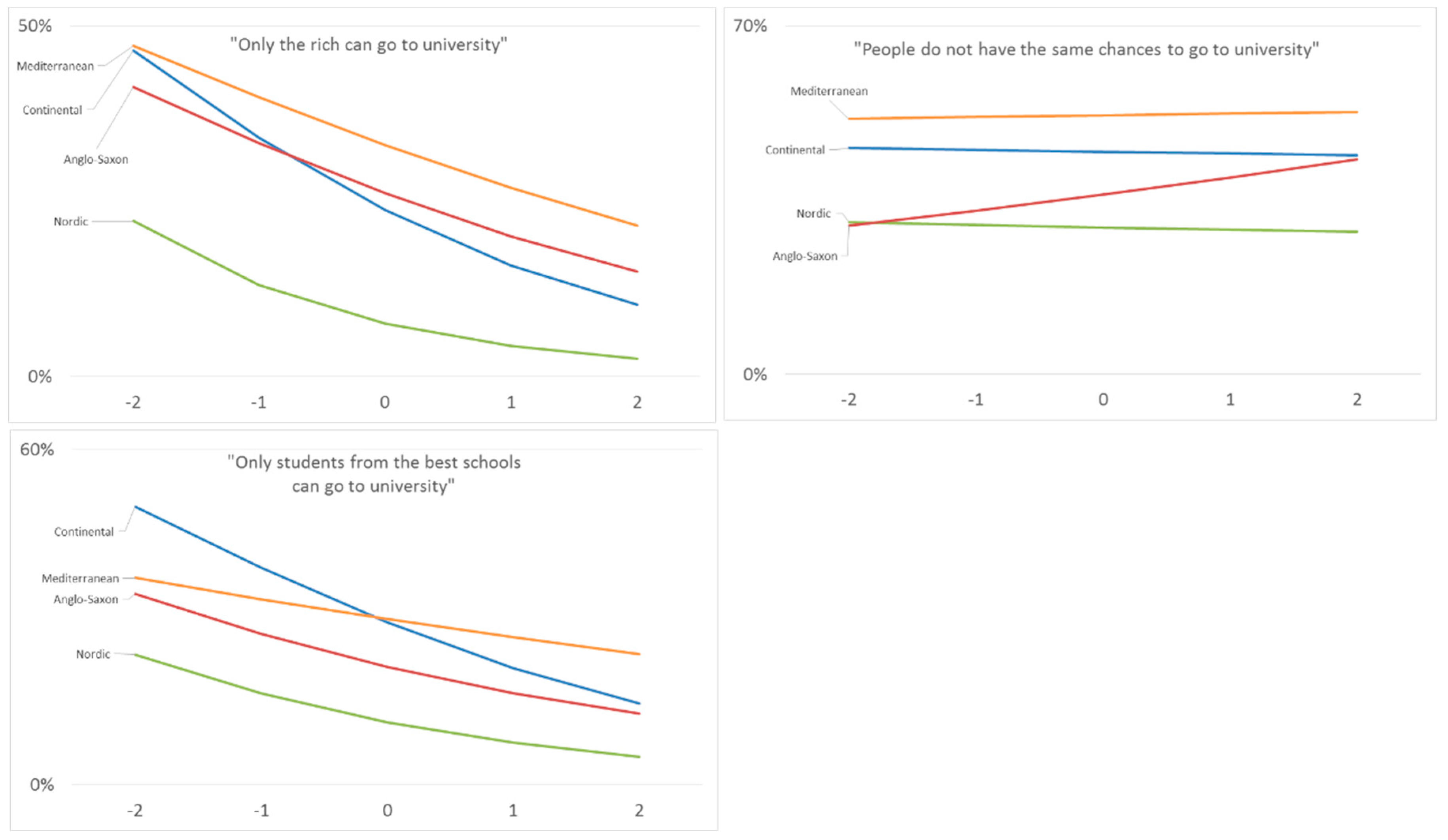

5.2. What Is Needed to Enter University?

5.2.1. Country Averages

5.2.2. Relationship with Educational Background

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonathan J. Mijs. “The unfulfillable promise of meritocracy: Three lessons and their implications for justice in education.” Social Justice Research 29 (2016): 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talcott Parsons. The Social System. Glencoe: Free Press, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Young. The Rise of the Meritocracy, 1870–2033: An Essay on Education and Equality. Baltimore: Penguin, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Saunders. “Might Britain Be a Meritocracy? ” Sociology 29 (1995): 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel Bell. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. New York: Basic Books Incorporated, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gary N. Marks. “Cross-national differences and accounting for social class inequalities in education.” International Sociology 20 (2005): 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Breen, Ruud Luijkx, Walter Müller, and Reinhard Pollak. “Nonpersistent inequality in educational attainment: Evidence from eight European countries.” American Journal of Sociology 114 (2009): 1475–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Breen, and John H. Goldthorpe. “Class, mobility and merit the experience of two British birth cohorts.” European Sociological Review 17 (2001): 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon Marshall, and Adam Swift. “Merit and mobility: A reply to Peter Saunders.” Sociology 30 (1996): 375–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaap Dronkers. “The importance of cognitive abilities at primary school for educational and occupational success in the life course of a Dutch generation, born around 1940.” In Paper presented at the Research Committee on Social Stratification at the 14th World Congress of Sociology, Montréal, QC, Canada, 26 July–1 August 1998.

- Yossi Shavit, and Hans Peter Blossfeld. Persistent Inequality: Changing Educational Attainment in Thirteen Countries. Social Inequality Series—ERIC; Boulder: Westview Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel Bowles, and Herbert Gintis. “The inheritance of inequality.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 16 (2002): 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbrand Tholen, Phillip Brown, Sally Power, and Annabelle Allouch. “The role of networks and connections in educational elites’ labour market entrance.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 34 (2013): 142–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutta Allmendinger. “Educational systems and labor market outcomes.” European Sociological Review 5 (1989): 231–50. [Google Scholar]

- Marius R. Busemeyer, and Christine Trampusch. The Political Economy of Collective Skill Formation. Oxford: University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent Dupriez, Xavier Dumay, and Anne Vause. “How do school systems manage pupils’ heterogeneity? ” Comparative Education Review 52 (2008): 245–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian F. Hannan, David Raffe, and Emer Smyth. Cross-National Research on School to Work Transitions: An Analytical Framework. Paris: OECD, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Margarita Estevez-Abe. “Social protection and the formation of skills: A reinterpretation of the welfare state.” In Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Edited by Peter A. Hall and David Soskice. Oxford: University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gosta Esping-Andersen. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kenn Ariga, Giorgio Brunello, Roki Iwahashi, and Lorenzo Rocco. “Why is the timing of school tracking so heterogeneous? ” Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) Discussion Paper No. 1854; Bonn, Germany: IZA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen Thelen. How Institutions Evolve. Cambridge: University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Margaret S. Archer. Social Origins of Educational Systems. London: Sage, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Marius R. Busemeyer. Skills and Inequality: Partisan Politics and the Political Economy of Education Reforms in Western Welfare States. Cambridge: University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Katarina Sass. “Understanding comprehensive school reforms: Insights from comparative-historical sociology and power resources theory.” European Educational Research Journal 14 (2015): 240–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michela Braga, Daniele Checchi, and Elena Meschi. “Institutional Reforms and Educational Attainment in Europe: A long run perspective.” Economic Policy 73 (2013): 45–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne West, and Rita Nikolai. “Welfare Regimes and Education Regimes: Equality of Opportunity and Expenditure in the EU (and US).” Journal of Social Policy 42 (2013): 469–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroslav Beblavy, Anna-Elisabeth Thum, and Marcela Veselkova. “Education Policy and Welfare Regimes in OECD Countries.” Modesto, CA, USA: Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) Working Document, CEPS, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Schroeder. “Integrating welfare and production typologies: How refinements of the varieties of capitalism approach call for a combination of welfare typologies.” Journal of Social Policy 38 (2009): 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutta Allmendinger, and Stephan Leibfried. “Education and the welfare state: The four worlds of competence production.” Journal of European Social Policy 13 (2003): 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeroen Lavrijsen, and Ides Nicaise. “New empirical evidence on the effect of educational tracking on social inequalities in reading achievement.” European Educational Research Journal 14 (2015): 206–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman Van de Werfhorst, and Jonathan J. Mijs. “Achievement inequality and the institutional structure of educational systems: A comparative perspective.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (2010): 407–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon Boone, and Mieke Van Houtte. “Social inequalities in educational choice at the transition from primary to secondary education: A matter of rational calculation? ” Kultura i Edukacja/Culture and Education 91 (2012): 188–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmut Ditton, and Jan Krusken. “Der Ubergang von der Grundschule in die Sekundarstufe.” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 9 (2006): 348–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie Duru-Bellat. Les Inégalités Sociales á L'école: Genèse et Mythes. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Breen, and John H. Goldthorpe. “Explaining educational differentials towards a formal rational action theory.” Rationality and Society 9 (1997): 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio Brunello, and Daniele Checchi. “Does school tracking affect equality of opportunity? New international evidence.” Economic Policy 22 (2007): 781–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric A. Hanushek, and Ludger Woessmann. “Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across countries.” Economic Journal 116 (2006): C63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Hattie. “Classroom composition and peer effects.” International Journal of Educational Research 37 (2002): 449–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Hattie. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. New York: Routledge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dion Burns, and Linda Darling-Hammond. Teaching around the World: What Can Talis Tell Us. Stanford: SCOPE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Andy Green, Francis Green, and Nicola Pensiero. “Cross-country variation in adult skills inequality.” Comparative Education Review 59 (2015): 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeroen Lavrijsen, and Ides Nicaise. “Social Inequalities in Early School Leaving: The Role of Educational Institutions and the Socioeconomic Context.” European Education 47 (2015): 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond Boudon. Education, Opportunity, and Social Inequality: Changing Prospects in Western Society. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Burgess, Deborah Wilson, and Ruth Lupton. “Parallel lives? Ethnic segregation in schools and neighbourhoods.” Urban Studies 42 (2005): 1027–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erica Frankenberg. “The role of residential segregation in contemporary school segregation.” Education and Urban Society 45 (2013): 548–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert D. Putnam. Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Markus Jantti, Bernt Bratsberg, Knut Roed, Oddbjorn Raaum, Robin Naylor, Eva Osterbacka, Anders Bjorklund, and Tor Eriksson. “American exceptionalism in a new light: A comparison of intergenerational earnings mobility in the Nordic countries, the United Kingdom and the United States.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 1938; Bonn, Germany: IZA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jaap Dronkers. Quality and Inequality of Education. Berlin: Springer, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ari Antikainen. “In search of the Nordic model in education.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 50 (2006): 229–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey Peter, Jason D. Edgerton, and Lance W. Roberts. “Welfare regimes and educational inequality: A cross-national exploration.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 20 (2010): 241–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne-Lise Arnesen, and Lisbeth Lundahl. “Still social and democratic? Inclusive education policies in the Nordic welfare states.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 50 (2006): 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natasha Kumar Warikoo, and Christina Fuhr. “Legitimating status: Perceptions of meritocracy and inequality among undergraduates at an elite British university.” British Educational Research Journal 40 (2014): 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamus Khan, and Colin Jerolmack. “Saying meritocracy and doing privilege.” The Sociological Quarterly 54 (2013): 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannu Räty, Leila Snellman, Hannele Mantesaari Hetekorpi, and Arja Vornanen. “Parents views on the comprehensive school and its development: A Finnish study.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 40 (1996): 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carla Shedd, and John Hagan. “Toward a developmental and comparative conflict theory of race, ethnicity, and perceptions of criminal injustice.” In The Many Colors of Crime: Inequalities of Race, Ethnicity, and Crime in America. New York: NYU Press, 2006, p. 313. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan J. Mijs. “Stratified failure: Educational stratification and students attributions of their mathematics performance in 24 countries.” Sociology of Education 89 (2016): 137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric A. Hanushek, Guido Schwerdt, Simon Wiederhold, and Ludger Woessmann. “Returns to skills around the world: Evidence from PIAAC.” European Economic Review 73 (2015): 103–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James R. Kluegel, and Eliot R. Smith. Beliefs about Inequality: Americans' Views of What Is and What Ought to Be. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer L. Hochschild. Facing up to the American Dream: Race, Class, And the Soul of the Nation. Princeton: University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz Dieter Meyer. “The rise and decline of the common school as an institution: Taking myth and ceremony seriously.” In The New Institutionalism in Education. Edited by Heinz Dieter Meyer and Brian Rowan. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz Dieter Meyer, and Brian Rowan. The New Institutionalism in Education. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vivien Schmidt. “Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse.” Annual Review Political Science 11 (2008): 303–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Tyack, and William Tobin. “The grammar of schooling: Why has it been so hard to change? ” American Educational Research Journal 31 (1994): 453–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerald K. LeTendre, Barbara K. Hofer, and Hidetada Shimizu. “What is tracking? Cultural expectations in the United States, Germany, and Japan.” American Educational Research Journal 40 (2003): 43–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Countries will be referred to with their two-letter ISO 3166 codes. The participating countries are Austria, AT; Flemish Region (Belgium), BE-F; Germany, DE; Italy, IT; Spain, ES; Portugal, PT; France, FR; Australia, AU; New Zealand, NZ; Great Britain, GB; United States, US; Denmark, DK; Finland, FI; Iceland, IS; Norway, NO; Sweden, SE.

| Geography | Members1 | Differentiation Mechanism | Vocational Education Enrolment | Production Regime | Welfare State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continental Europe | AT, BE-F, DE | Early tracking | High | Medium skills | Conservative |

| Mediterranean | IT, ES, PT, FR | Grade retention | Low/Medium | Low skills | Mediterranean |

| Anglo-Saxon | AU, NZ, GB, US | Ability grouping | Low | Polarisation | Liberal |

| Nordic | DK, FI, IS, NO, SE | Individual integration | Medium/High | Medium skills | Social-democratic |

| Main source | [16] | [17] | [18] | [19] |

| A—How Important Is…to Get ahead in Life? | |

| Ascribed assets | Coming from a wealthy family |

| Having well-educated parents | |

| A person’s race | |

| Knowing the right people | |

| Individual responsibility assets | Having a good education |

| Hard work | |

| Having ambition | |

| B—How Much Do You Agree or Disagree with Each of the Following Statements? | |

| Equal opportunities in the access to university | Only students from the best secondary schools have a good chance to obtain a university education |

| Only the rich can afford the costs of attending university | |

| People have the same chances to enter university, regardless of their gender, ethnicity or social background | |

| Country | Sample Size | Average Schooling Years | Country | Sample Size | Average Schooling Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continental | Anglo-Saxon | ||||

| AT | 1019 | 11.4 | AU | 1525 | 12.6 |

| BE-F | 1115 | 12.2 | NZ | 935 | 14.2 |

| DE | 1395 | 11.1 | GB | 958 | 12.4 |

| Nordic | US | 1581 | 13.6 | ||

| DK | 1518 | 12.8 | Mediterranean | ||

| FI | 880 | 13.0 | FR | 2817 | 13.4 |

| IS | 947 | 14.1 | IT | 1084 | 10.5 |

| NO | 1456 | 14.6 | PT | 1000 | 8.8 |

| SE | 1137 | 12.6 | ES | 1215 | 12.5 |

| Ascribed Assets | Individual Responsibility | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealthy Family | Educated Parents | Race | Network | Own Education | Hard Work | Ambition | |

| AT | 31 | 36 | 18 | 61 | 79 | 67 | 75 |

| BE-F | 14 | 39 | 12 | 53 | 73 | 65 | 57 |

| DE | 29 | 50 | 17 | 65 | 92 | 71 | 79 |

| Continental (average) | 25 | 42 | 16 | 59 | 81 | 68 | 70 |

| DK | 9 | 18 | 6 | 35 | 59 | 44 | 65 |

| FI | 6 | 10 | 4 | 31 | 54 | 64 | 52 |

| IS | 11 | 30 | 9 | 37 | 70 | 93 | 90 |

| NO | 11 | 14 | 16 | 36 | 50 | 81 | 88 |

| SE | 14 | 21 | 7 | 40 | 64 | 76 | 84 |

| Nordic (average) | 10 | 19 | 8 | 36 | 59 | 71 | 76 |

| AU | 22 | 39 | 8 | 40 | 78 | 88 | 82 |

| GB | 15 | 32 | 9 | 34 | 75 | 85 | 72 |

| NZ | 9 | 26 | 6 | 29 | 72 | 90 | 83 |

| US | 31 | 50 | 10 | 45 | 89 | 96 | 92 |

| Anglo-Saxon (average) | 19 | 37 | 8 | 37 | 78 | 90 | 82 |

| ES | 32 | 53 | 11 | 53 | 70 | 68 | 57 |

| FR | 10 | 44 | 9 | 22 | 66 | 55 | 61 |

| IT | 37 | 35 | 12 | 62 | 75 | 63 | 61 |

| PT | 35 | 34 | 11 | 46 | 58 | 87 | 72 |

| Mediterranean (average) | 29 | 41 | 10 | 46 | 67 | 68 | 63 |

| Only Students from the Best School | Only the Rich | Not the Same Chances | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 23 | 17 | 39 |

| BE-F | 34 | 24 | 42 |

| DE | 31 | 35 | 56 |

| Continental (average) | 29 | 26 | 45 |

| DK | 12 | 8 | 30 |

| FI | 14 | 8 | 32 |

| IS | 14 | 11 | 27 |

| NO | 10 | 5 | 22 |

| SE | 12 | 11 | 36 |

| Nordic (average) | 12 | 9 | 29 |

| AU | 24 | 36 | 36 |

| GB | 29 | 29 | 46 |

| NZ | 12 | 16 | 28 |

| US | 21 | 26 | 34 |

| Anglo-Saxon (average) | 22 | 27 | 36 |

| ES | 22 | 20 | 43 |

| FR | 46 | 57 | 56 |

| IT | 21 | 20 | 51 |

| PT | 28 | 37 | 58 |

| Mediterranean (average) | 29 | 34 | 52 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lavrijsen, J.; Nicaise, I. Ascription, Achievement, and Perceived Equity of Educational Regimes: An Empirical Investigation. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040064

Lavrijsen J, Nicaise I. Ascription, Achievement, and Perceived Equity of Educational Regimes: An Empirical Investigation. Social Sciences. 2016; 5(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleLavrijsen, Jeroen, and Ides Nicaise. 2016. "Ascription, Achievement, and Perceived Equity of Educational Regimes: An Empirical Investigation" Social Sciences 5, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040064

APA StyleLavrijsen, J., & Nicaise, I. (2016). Ascription, Achievement, and Perceived Equity of Educational Regimes: An Empirical Investigation. Social Sciences, 5(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040064