Engaging Citizen Participation—A Result of Trusting Governmental Institutions and Politicians in the Portuguese Democracy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

- (1)

- communication between citizens to define public goals

- (2)

- tolerance and acceptance of pluralism

- (3)

- consensus on democratic procedures

- (4)

- civic awareness among the actors competing for different purposes

- (5)

- citizen participation in governing organizations.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robert E. Goodin, and John S. Dryzek. “Deliberative Impacts: The macro-political uptake of mini-public.” Politics Society 34 (2006): 219–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archon Fung. “Minipublics: Deliberative Designs and their consequences.” In Deliberation, Participation and Democracy: Can the People Govern? Edited by Shawn W. Rosenberg. Nova Iorque: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vanda Carreira, João Reis Machado, and Lia Vasconcelos. “Citizens’ Education Level and Public Participation in Environmental and Spatial Planning Public Policies: Case Study in Lisbon and Surrounds Counties.” International Journal of Political Science 2 (2016): 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vanda Carreira, João Reis Machado, and Lia Vasconcelos. “Legal citizen knowledge and public participation on environmental and spatial planning policies: A case study in Portugal.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research 2 (2016): 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Archon Fung, and Erik Olin Wright. Deepening Democracy: Institutional Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance. London: Verso, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luiz César de Queiroz Ribeiro, and Orlando Alves dos Santos Junior. “Democracia e cidade: Divisão social da cidade e cidadania na sociedade brasileira.” Análise Social 174 (2005): 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio César Bochenek. (Ine)eficácia da Implementação da lei de Cotas Para Mulheres na Politica Brasileira. Relações de Trabalho, Desigualdades Sociais e Sindicalismo. Coimbra: Faculty of Economy, University of Coimbra Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loïc Blondiaux. Le Nouvel Esprit de la Démocratie. Paris: Seuil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- António R. G. Lamas. “Síntese e recomendações: O desenvolvimento da eco—Cidadania.” In Participação Pública e Planeamento. Prática da Democracia Ambiental. Edited by José Alfredo Jacinto. Lisboa: FLAD, 1996, pp. 241–46. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Prescott-Allen. Barometer of Sustainability: Measuring and Communicating Wellbeing and Sustainable Development. Cambridge: IUCN, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Prescott-Allen. Assessing Progress toward Sustainability: The System Assessment Method Illustrated by the Wellbeing of Nations. Cambridge: IUCN, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Prescott-Allen. The Wellbeing of Nations: A Country-by-Country Index of Quality of Life and the Environment. Washington: Island Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. Beierle, and Jerry Cayford. Democracy in Practice: Public Participation in Environmental Decisions. Washington: Resources for the Future, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- José Joaquim Gomes Canotilho. Direito Constitucional & Teoria da Constituição, 7th ed. Coimbra: Almedina, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Gomes. “Apontamentos Sobre o Conceito de Esfera Pública Política.” In Mídia, Esfera Pública e Identidades Coletivas. Edited by Rousiley Maia and Maria Céres Pimenta Spínola Castro. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre André, Bert Enserink, Desmond Connor, and Peter Croal. Public Participation International Best Practice Principles. Special Publication. Series No. 4. Fargo: International Association for Impact Assessment, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsty L. Blackstock, G. J. Kelly, and B. L. Horsey. “Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability.” Ecological Economics 60 (2007): 726–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula Antunes, Giorgos Kallis, Nuno Videira, and Rui Santos. “Participation and evaluation for sustainable river basin governance.” Ecological Economics 68 (2009): 931–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanda Carreira. “Urbanism and Depressive Syndrome.” Master Thesis, New University of Lisbon, Caparica, Portugal, 11 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Schudson. “What if civic life didn’t die? ” American Prospect 25 (1996): 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- G. Orduna. Sebenta de Apoio ao Master em Desenvolvimento Local Internacional, 1st ed. Madrid: Instituto de Economia y Geografia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2003, p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Carlos Milani. “O princípio participativo na formulação de políticas públicas locais: Análise comparativa de experiências européias e latino-americanas.” In CD-Rom do XXIX Encontro da ANPOCS. Caxambu: ANPOCS, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- David W. Cash, William C. Clark, Frank Alcock, Nancy M. Dickson, Noelle Eckley, David H. Guston, Jill Jäger, and Ronald B. Mitchell. “Knowledge systems for sustainable development.” PNAS 100 (2003): 8066–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond Quivy, and Luc Van Campenhoudt. Manual de Investigação em Ciências Sociais, 2nd ed. Lisboa: Gradiva, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Quinn Patton. Utilization-Focused Evaluation, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marc Hooghe, and Yves Dejaeghere. “Does the ‘Monitorial Citizen’ Exist? An Empirical Investigation into the Occurrence of Postmodern Forms of Citizenship in the Nordic Countries.” Scandinavian Political Studies 30 (2007): 249–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erik Amnå, and Joakim Ekman. “Standby citizens: Diverse faces of political passivity.” European Political Science Review 6 (2014): 261–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha Nussbaum. “Women and equality: The capabilities approach.” International Labour Review 138 (1999): 227–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David M. Chavis, and Abraham Wandersman. “Sense of community in the urban environment: A catalyst for participation and community development.” American Journal of Community Psychology 18 (1990): 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John E. Prestby, Abraham Wandersman, Paul Florin, Richard Rich, and David Chavis. “Benefits, costs, incentives management and participation in voluntary associations.” American Journal of Community Psychology 18 (1990): 117–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc A. Zimmerman, and Julian Rappaport. “Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment.” American Journal of Community Psychology 16 (1988): 725–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank Fischer. “Participatory governance as deliberative empowerment. The cultural politics of discursive space.” American Review of Public Administration 36 (2006): 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terri Mannarini, and Angela Fedi. “The quality of participation in the perception of citizens: Findings from a qualitative study.” In Community Psychology: New Developments. Edited by Niklas Lange and Marie Wagner. Happauge: Nova Science, 2010, pp. 177–92. [Google Scholar]

- Terri Mannarini, Angela Fedi, and Stefania Trippetti. “Public involvement: How to encourage citizen participation.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 20 (2010): 262–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias Finger. “NGOs and transformation: Beyond social movement theory.” In Environmental NGOs in World Politics: Linking the Local and the Global. Edited by Tomas Princen and Matthias Finger. London: Routledge, 1994, pp. 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Carolyn Kagan. “Pillars of support for well-being in the community: The role of the public sector.” In Paper presented at the Wellbeing and Sustainable Living Seminar, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK, 24 May 2007; Available online: http://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/17972/2/Pillars-of-support-for%20wellbeing.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2016).

- Hedayat Allah Nikkhah, and Maarof Redzuan. “Participation as a medium of empowerment in community development.” European Journal of Social Sciences 11 (2009): 170–76. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Mainwaring, and Mariano Torcal. “Party system institutionalization and party system theory after the third wave of democratization.” Handbook of Party Politics 11 (2006): 204–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardo Morlino. “What is a ‘Good’ Democracy? Theory and Empirical Analysis.” In Paper presented at the European Union, Nations State, and the Quality of Democracy, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 31 October–2 November 2002.

- Joseph S. Nye, Philip Zelikow, and David C. King. Why People Don’t Trust Government. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pippa Norris. Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Margaret Levi. “A State of Trust.” In Trust and Governance. Edited by Valerie Braithwaite and Margaret Levi. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Subodh P. Kulkarni. “Environmental ethics and information asymmetry among organizational stakeholders.” Journal of Business Ethics 27 (2000): 215–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark C. Suchman. “Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches.” The Academy of Management Review 20 (1995): 571–610. [Google Scholar]

- Guido Palazzo, and Andreas Georg Scherer. “Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework.” Journal of Business Ethics 66 (2006): 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Siegrist, George T. Cvetkovich, and Heinz Gutscher. “Shared values, social trust, and the perception of geographic cancer clusters.” Risk Analysis 21 (2001): 1047–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susan J. Pharr, and Robert D. Putnam, eds. Disaffected Democracies: What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries? Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Richard Gunther, José Ramón Montero, and Juan Linz, eds. Political Parties: Old Concepts and New Challenges. Oxford: OUP, 2002.

- Paulo N. Lopes, Marc A. Brackett, John B. Nezlek, Astrid Schütz, Ina Sellin, and Peter Salovey. “Emotional Intelligence and Social Interaction.” Society for Personality and Social Psychology 30 (2004): 1018–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. A. Moises. “Citizens’ Evaluation of Democratic Institutions and the Quality of Democracy in Brazil.” In Paper presented at the 20th IPSA World Congress, Fukuoka, Japan, 8–13 July 2006.

- Rachel Meneguello. Grounds for Democratic Adherence: Brazil, 2002–2006. Santiago de Chile: Informe Latinobarómetro, Corporación Latinobarómetro, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- S. Silva. “Participação política e Internet: Propondo uma análise teórico-metodológica a partir de quatro conglomerado de fatores.” In Trabalho Apresentado no GT Internet e Política do I Congresso Anual da Associação Brasileira de Pesquisadores de Comunicação e Política, Ocorrido na Universidade Federal da Bahia—Salvador-BA. Salvador da Baía: Brasil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Michelle Lessard-Hébert, Gabriel Goyette, Gérald Boutin, and Maria João Reis. Investigação Qualitativa—Fundamentos e Práticas, 5th ed. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Censos 2011 Resultados Definitivos—Portugal. Lisboa: Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardo Morlino. Democracy between Consolidation and Crisis. Parties, Groups and Citizens in Southern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Norberto Bobbio. The Future of Democracy: A Defence of the Rules of the Game. Bellamy: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Juan J. Linz, and Alfred Stepan. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Axel Hadenius. Institutions and Democratic Citizenship. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mark E. Warren. Democracy and Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rachel Meneguello. “Grounds for Democratic Adherence: Brazil, 2002–2006.” Informe Latinobarómetro, Corporación Latinobarómetro, Santiago de Chile. 2006. Available online: http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/etext/llilas/vrp/meneguello.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2016).

- Kaifeng Yang, and Marc Holzer. “The Performance-Trust Link: Implications for Performance Measurement.” Public Administration Review 66 (2006): 114–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel Ángel López-Navarro, Jaume Llorens-Monzonís, and Vicente Tortosa-Edo. “The Effect of Social Trust on Citizens’ Health Risk Perception in the Context of a Petrochemical Industrial Complex.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10 (2013): 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouter Poortinga, and Nick F. Pidgeon. “Exploring the dimensionality of trust in risk regulation.” Risk Analysis 23 (2003): 961–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denise M. Rousseau, Sim B. Sitkin, Ronald S. Burt, and Colin Camerer. “Not so different after all: Across-discipline view of trust.” The Academy of Management Review 23 (1998): 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald Inglehart, and Wayne E. Baker. “Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values.” American Sociological Review 65 (2000): 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald Inglehart, and Christian Welzel. “Political Culture and Democracy.” In New Directions in comparative Politics. Edited by Howard Wiarda. New York: Westview Press, 2002, pp. 141–64. [Google Scholar]

- James L. Gibson. “The legitimacy of the U.S. Supreme Court in a polarized polity.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 4 (2007): 507–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James L. Gibson, and Gregory A. Caldeira. Citizens, Courts, and Confirmation: Positivity Theory and the Judgments of the American People. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen Tsang, Margarett Burnett, Peter Hills, and Richard Welford. “Trust, public participation and environmental governance in Hong Kong.” Environmental Policy and Governance 19 (2009): 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilita Seimuskane, and Maija Vorlsava. “Citizen’s Trust in Public Authorities of Latvia and Participatory Paradigm.” European Scientific Journal 9 (2013): 280–90. [Google Scholar]

- María Victoria de Mesquita Benevides. Cidadania e Democracia. São Paulo: Lua Nova, 1994, pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- María Victoria de Mesquita Benevides. A Cidadania Ativa: Referendo, Plebiscito E Iniciativa Popular. São Paulo: Editora-Ática, 1994, p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Judith E. Innes. “Consensus building: Clarifications for the critics.” Planning Theory 3 (2004): 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathleen E. Halvorsen. “Critical next steps in research on public meetings and environmental decision-making.” Human Ecology Review 13 (2006): 150–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jens Newig, and Oliver Fritsch. “Environmental governance: Participatory, multi-level—And effective? ” Environmental Policy and Governance 19 (2009): 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemma Carr, G. Blöschl, and Pete Loucks. “Evaluating participation in water resource management: A review.” Water Resources Research 48 (2012): W11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen Quintelier, and Jan W. van Deth. “Supporting Democracy: Political Participation and Political Attitudes. Exploring Causality Using Panel Data.” Political Studies 62 (2014): 153–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunobu Maeda, and Makota Miyahara. “Determinants of trust in industry, government, and citizen’s groups in Japan.” Risk Analysis 23 (2003): 303–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotr Sztompka. Trust: A Sociological Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kay Lehman Schlozman, Sidney Verba, and Henry E. Brady. The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin R. Barber. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Robert A. Dahl, and Ian Shapiro. On Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Steven J. Rosenstone, and John Mark Hansen. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: Macmillan, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jane Mansbridge. “On the Idea that Participation Makes Better Citizens.” In Citizen Competence and Democratic Institutions. Edited by Stephen L. Elkin and Karol Edward Soltan. Pennsylvania: University Press, 1999, pp. 291–325. [Google Scholar]

- Sofie Marien, Marc Hooghe, and Ellen Quintelier. “Inequalities in Non-Institutionalised Forms of Political Participation: A Multi-Level Analysis of 25 Countries.” Political Studies 58 (2010): 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin J. Newman, and Brandon L. Bartels. “Politics at the Checkout Line: Explaining Political Consumerism in the United States.” Political Research Quarterly 64 (2011): 803–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Berger. “Political Theory, Political Science and the End of Civic Engagement.” Perspectives on Politics 7 (2009): 335–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea Cornwall, and Rachel Jewkes. “What is participatory research? ” Social Science and Medicine 12 (1995): 1667–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolyn Kagan. “Making a Difference: Participation and Wellbeing.” Renew Intelligence Report, School of Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. 2006. Available online: http://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/24692/ (accessed on 12 April 2016).

- Tom R. Tyler. “Trust and Democratic Governance.” In Trust and Governance. Edited by Valerie Braithwaite and Margaret Levi. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Democratizar a Democracia: Os Caminhos da Democracia Participativa. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jose Sanchez Parga. “Del Conflicto Social al Ciclo Político de la Protesta.” Ecuador Debate 64 (2005): 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Salete Souza de Amorim. “Cidadania e Participação Democrática.” Anais do II Seminário Nacional, Movimentos Sociais, Participação e Democracia, UFSC, Florianópolis, Brasil, 25–27 de Abril 2007. Available online: http://www.plataformademocratica.org/Publicacoes/7055_Cached.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2016).

- Pippa Norris. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. Dalton. The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation is Reshaping American Politics. Washington: CQ Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marc Hooghe, and Soetkin Verhaegen. “The effect of political trust and trust in European citizens on European identity.” European Political Science Review 1 (2015): 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave Mckenna. “UK Local Government and Public Participation: Using Conjectures to Explain the Relationship.” Public Administration 89 (2011): 1182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemma Carr. “Stakeholder and public participation in river basin management—An introduction.” Wires Water 2 (2015): 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gene Rowe, and Lynn J. Frewer. “Public participation methods: A framework for evaluation.” Science Technology Human Values 25 (2000): 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary GrisezKweit, and Robert W. Kweit. “Citizen Participation: Enduring Issues for the Next Century.” National Civic Review 76 (1987): 191–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre Blais. “Political Participation.” In Comparing Democracies 3: Elections and Voting in the 21st Century. Edited by Lawrence LeDuc, Richard G. Niemi and Pippa Norris. Los Angeles: Sage, 2010, pp. 164–83. [Google Scholar]

- Edwin Odhiambo Siala. “Factors Influencing Public Participation in Budget Formulation. The Case of Nairobi County.” Ph.D. Dissertation, United States International University, Nairobi City, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | N | Category | Fr | F (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 250 | 42.30 | <20 years | 4 | 1.6 | |

| 20–30 years | 38 | 15.2 | ||||

| SD | 13.24 | 30–40 years | 78 | 31.2 | ||

| 40–50 years | 58 | 23.2 | ||||

| min. | 14 | 50–60 years | 44 | 17.6 | ||

| max. | 71 | 60–70 years | 20 | 8.0 | ||

| >=70 years | 8 | 3.2 | ||||

| Gender | 250 | Male | 120 | 48.0 | ||

| Marital state | 250 | Female | 130 | 52.0 | ||

| Single | 88 | 35.2 | ||||

| Married | 92 | 36.8 | ||||

| Divorced | 68 | 27.2 | ||||

| Widower | 2 | 0.8 | ||||

| Education level | 250 | Without education | 14 | 5.7 | ||

| 1st cycle | 12 | 4.9 | ||||

| 2nd cycle | 50 | 20.3 | ||||

| 3th cycle | 30 | 12.2 | ||||

| 12th Year | 18 | 7.3 | ||||

| Bachelor | 18 | 7.3 | ||||

| Integrated Master | 88 | 35.8 | ||||

| Master of Science | 10 | 4.1 | ||||

| Doctoral | 6 | 2.4 | ||||

| Pop and politicians should plan the land together | 250 | Yes | 242 | 96.6 | ||

| No | 8 | 3.4 | ||||

| Reasons to participate in planning | 250 | Knows better who lives in the places | 247 | 98.8 | ||

| Like to participate in political processes | 3 | 1.2 | ||||

| Time point to be involved in policies | 250 | From the beginning of draft | 206 | 82.4 | ||

| During the draft of plan | 40 | 16.0 | ||||

| After the draft of plan | 4 | 1.6 | ||||

| Opinion about government | 250 | Do not listen pop. opinion | 222 | 88.8 | ||

| Do not consider pop. opinion | 182 | 72.6 | ||||

| Politicians just don’t want to know | 197 | 78.8 | ||||

| They are not close to pop. | 23 | 9.1 | ||||

| Type of participation on policies | 250 | If required | 74.6 | |||

| Voluntary | 25.4 | |||||

| Promoting the motivation for participation | 250 | If pop. think that their opinion counts | 60.1 | |||

| If pop. think that politicians try to change things | 7.8 | |||||

| If the people were paid for | 7.8 | |||||

| Measures to increase citizens’ participation | 250 | Request directly their participation | 50.0 | |||

| If politicians were nice | 16.5 | |||||

| If politicians, consider the pop. opinions | 12.2 | |||||

| Common Parameter | Parameters | Chi-Square Test p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Public participation level | What citizens think about whether the covenant of rulers hears or does not hear their opinion | 0.769 |

| What citizens think about the idea that decisions and actions taken by politicians are based on the opinion of the population | 0.810 | |

| Do the citizens understand or not the politicians’ decisions and actions | 0.011 * | |

| Type of evaluation that every citizen attaches to the actions and/or decisions taken and the local political power | 0.14 * |

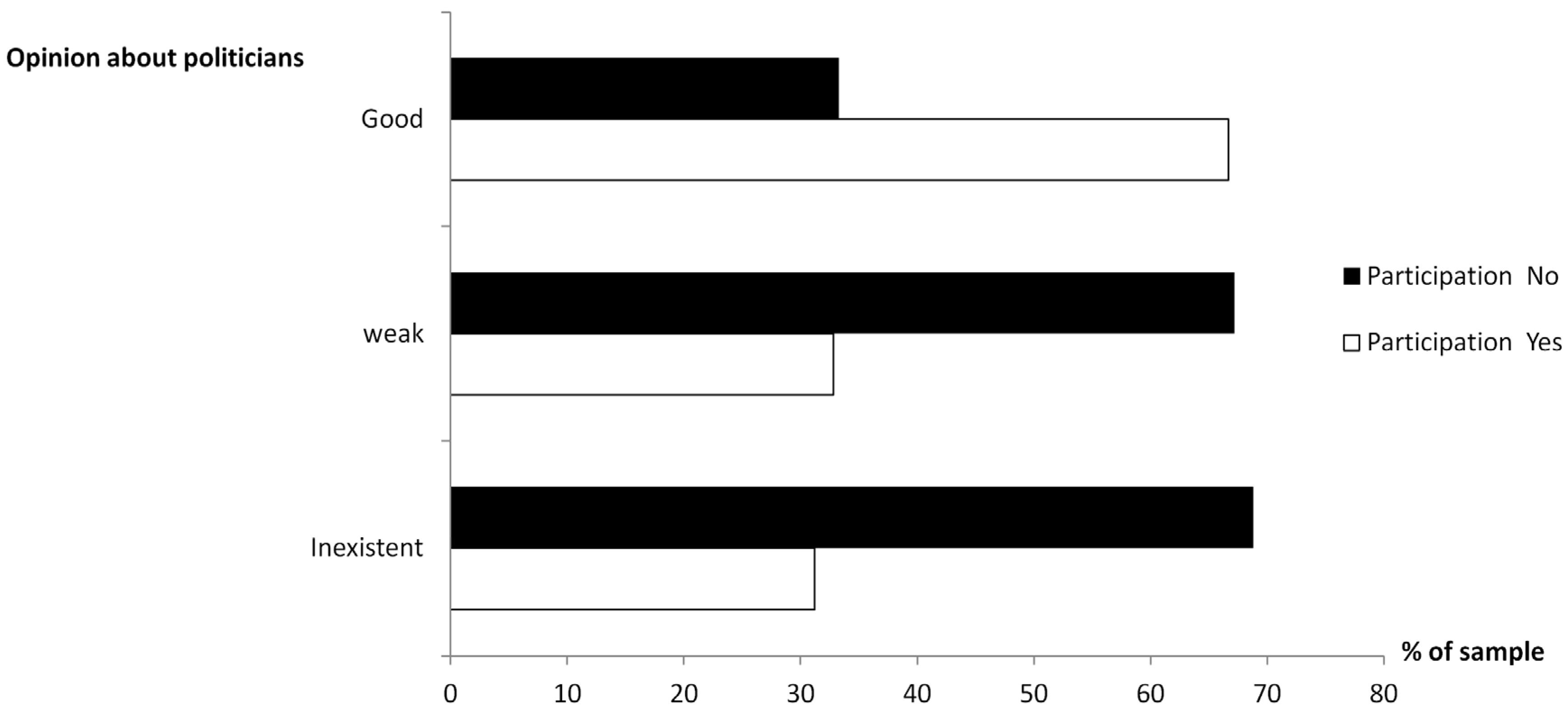

| Evaluation of Politicians Actions on Improvement of Life Quality | Public Participation Level | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | ||

| Nonexistent | 31.3% | 68.8% | 0.174 |

| Weak | 32.8% | 67.2% | |

| Good | 66.7% | 33.3% | |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carreira, V.; Machado, J.R.; Vasconcelos, L. Engaging Citizen Participation—A Result of Trusting Governmental Institutions and Politicians in the Portuguese Democracy. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030040

Carreira V, Machado JR, Vasconcelos L. Engaging Citizen Participation—A Result of Trusting Governmental Institutions and Politicians in the Portuguese Democracy. Social Sciences. 2016; 5(3):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030040

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarreira, Vanda, João Reis Machado, and Lia Vasconcelos. 2016. "Engaging Citizen Participation—A Result of Trusting Governmental Institutions and Politicians in the Portuguese Democracy" Social Sciences 5, no. 3: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030040

APA StyleCarreira, V., Machado, J. R., & Vasconcelos, L. (2016). Engaging Citizen Participation—A Result of Trusting Governmental Institutions and Politicians in the Portuguese Democracy. Social Sciences, 5(3), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030040