Abstract

The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) announced the formation of the “Islamic Caliphate” as an alternative to modern states, on 29 June 2014 (the first day of Ramadan). The ISIS vision shared by other global jihadist organizations such as al-Qaeda is an apocalyptic post-state. Many authors very quickly evolve from the idea of the potential threat to either the U.S. or its allies to a requisite necessity of strong military action by the U.S. to defeat ISIS. Something frequently absent in analyses of U.S. reactions to ISIS is the capabilities, responsibilities, and opinions and desires of neighboring Gulf countries. This paper will incorporate attitudes and opinions of Gulf countries to imply responsibilities to deal with ISIS prior to considering potential U.S. actions.

Keywords:

Islamic State; ISIS; ISIL; Daesh; caliphate; Salafism; al-Qaeda in Iraq; Sunni-Shiite split 1. Introduction

The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) announced the formation of the “Islamic Caliphate” as an alternative to modern states, on 29 June 2014 (the first day of Ramadan) [1,2]. The ISIS vision shared by other global jihadist organizations such as al-Qaeda is an apocalyptic post-state [3,4]. Despite the description of ISIS by Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs Brett McGurk [5] as merely an increasing “…threat to U.S. interests”, many authors ([6]; [7], p. 6) very quickly evolve from the idea of the potential threat to either the U.S. or its allies to a requisite necessity of strong military action by the U.S. to defeat ISIS. Kelly argues that “…it is imperative that the U.S. works to diminish and ultimately destroy the group.” Lewis ([6], p. 4) evolves from “…ISIS is broadcasting the intent to attack Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the West. The threat of attacks against the U.S. is present” to conclude with the statement: “ISIS is already a threat to the United States.” Lewis continues, “It is therefore necessary for the U.S. to consider ways to defeat ISIS, not only to preserve the integrity of the Iraqi state, but to preserve our own security” ([6], p. 4). Something frequently absent in analyses of U.S. reactions to ISIS is the capabilities, responsibilities, and opinions and desires of neighboring Gulf countries. This paper will incorporate the attitudes and opinions of Gulf countries to imply responsibilities to deal with ISIS prior to considering potential U.S. actions. First, an introduction to ISIS is articulated through a discussion of Salafism and the Shiite-Sunni divide. After briefly describing the current U.S. strategy for dealing with ISIS, the paper will describe the attitudes and responsibilities of Gulf neighbors before contemplating potential future U.S. strategies.

This short treatise discusses U.S. actions in response to the Islamic State, eventually concluding the best response is not for the U.S. to military act decisively to defeat the Islamic State. Instead, a new day is dawning where Gulf states are teaming up to provide their own defense (in this instance led by Saudi Arabia), despite considerable political differences of member countries. This local defense may or may not ever lead to the outright destruction of the Islamic State. Research emphasis is placed on revealing attitudes of and actions by neighboring Gulf states who must live with a post-conflict environment, if one is ever reached. The paper provides a solid theoretical background to begin a new conversation that asks questions such as what are the impacts of locally-led coalitions with respect to balancing the power of Iran, etc., but these follow-up questions exceed the scope of this research which seeks merely to begin a new line of thinking in the literature, where the U.S. plays a supporting role in the region.

2. Discussion

Background of ISIS: this section describes the Islamic state by introducing Salafism beliefs in Islam and the Shiite-Sunni divide, and how those concepts shaped the war in Iraq, the maturation of Al Qaeda into the Islamic state.

2.1. Salafism

Salafists believe that Islam has become poisoned by modernity and has strayed from its origins [8]. Salafism is an ultraconservative form of Sunni Islam where a direct adherence to the originally written texts and teachings of the prophet Mohammed should guide our everyday lives. Many jihadi movements use the Salafist ideology as a backdrop for their own agendas ([9], p. 8).

The Shiite-Sunni Divide

Upon the death of the prophet Mohammed, Muslims were divided in choosing his successor as their religious leader in the Caliphate, a political-religious state comprising the Muslim community and the lands and people under its dominion. Many felt the next religious leader should be chosen by the Muslim community (the Sunnis), while others (the Shia) felt the succession should be more akin to royal lineages of kings and queens: the next Muslim leader should be the son-in-law of Mohammed, as declared by Mohammed before his death. Shias are concentrated in southern Lebanon and Iraq, Iran, and also live in some parts of other Persian Gulf countries (e.g., Saudi Arabia) [10].

2.2. War in Iraq

2.2.1. Changing Scope of the War

The more recent wars in Iraq were results following prior wars, dating back to the American-led expulsion of Iraq from Kuwait over 20 years ago. The American invasion of Iraq in 2003 was followed by a civil war between Shia and Sunni Muslims, but the context always remained within the regional dilemmas of all the neighboring countries.

2.2.2. Iraq and Its Neighbors

As Gonzalez [11] argues in his book, one of the Bush administration’s most tragic actions was its insistence on approaching Iraq as if it existed in a vacuum. “For too long, we have treated sectarian tensions as community-level challenges, issues that could somehow be solved if we put enough boots on the ground or made token political gestures aimed at reconciliation,” however, Gonzalez [12] contends, the Sunni-Shia conflict has very little to do with personal religious grudges. It is a regional-level phenomenon that has been pursued repeatedly by powerful countries seeking regional influence. To fix Iraq, we have to fix how its neighbors deal with one another. Following the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the “Coalition Provisional Authority” was established as a transitional government led by Paul Bremer who issued a directive calling for the “de-Ba’athification” of the Iraqi government [13], which afforded an opportunity for Shia in Iraq to seek revenge for their many instances of inhuman treatment (e.g., after the 1991 Gulf War; however, Hussein’s military brutally cracked down on these Shia rebels, killing tens of thousands of people [11], p. 100). Many Sunnis joined the growing insurgency opposed to the U.S. occupation ([14], p. 5).

2.2.3. Al-Qaeda in Iraq

By this time, ultraconservative Sunni jihadists from throughout the Middle East began to cross into Iraq, al-Qaeda and Tawheed wa’al Jihad (founded by Jordanian native Abu Musab Zarqawi) among them [14]. Tawheed wa’al Jihad was the precursor to ISIS. The eventual formation of the interim government (led nearly exclusively by Shia) fed the insurgency. Al-Qaeda and other radical jihadist groups gained support from many Sunni tribes.

2.2.4. Brief Affiliation with Al-Qaeda

Tawheed wa’al Jihad provided Sunni communities with guidance and protection, and Zarqawi assured Sunnis that they were performing their religious duty by fighting coalition forces. These jihadist groups also used propaganda to win the allegiance of Sunnis, claiming that the Americans were working with the Shia and Iran to expel Sunnis from Iraq ([14], p. 8). In October 2004, Osama bin Laden officially endorsed Zarqawi and renamed his group “al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)” [15], but Zarqawi had his own agenda, which included inciting the Iraqi government to retaliate against the Sunni populace, so that Sunnis had no choice but to support al-Qaeda in Iraq. By 2006, Zarqawi viewed himself as the “caliph”, or a spiritual leader, and AQI began to impose its harsh interpretation of Sharia Islamic law on Sunni communities ([7], p. 18). Resentment from those who had joined the insurgency combined with a renewed American offensive in 2007 depleted Zarqawi’s army by over 70%, from 12,000 to 3500. By 2009, al-Qaeda in Iraq was effectively defeated as an army [16]. The relative peace was short-lived, as civil war erupted in Syria in 2011, drawing the remnants of AQI from Iraq to Syria.

2.3. Civil War in Syria Leading to ISIS

The new leader of AQI, Abu al-Baghdadi, sent fighters into Syria to join the opposition in fighting al-Assad. AQI, now calling themselves the “Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant” (referred to as both ISIL and ISIS), was the most powerful rebel group in the country, fighting Assad’s regime within one year [17]. Meanwhile, back in Iraq the ruling government persecuted Sunnis, including the arrest of the vice president, the most senior Sunni in the government, the arrest of thousands of other Sunnis, and also the death of Sunnis at the hands of roaming Shia militias [17]. Seeing Sunni protests throughout Iraq, the defeated AQI (now ISI) saw its opportunity to address their loss by moving back into Iraq, seeking to establish the “Islamic Caliphate.” While it might be hard to understand how any Iraqi Sunnis could consider joining ISIS after their experience with AQI, for some it seems that joining ISIS was their only chance. Furthermore, upon their return to Iraq, ISIS was able to boast of success on the battlefield and their ability to govern.

2.4. ISIS Caliphate

One key reason ISIS has legitimacy among some Muslims as a caliphate is due to their combined ability to wage war and also build state capacity, two key features of their success [18]. According to the Dabiq Magazine, the ISIS grand strategy is predicated upon military force to establish physical control before political and religious authority is attained [19]. The phases ([6], p. 11) of their grand strategy are described in Dabiq Magazine [19] as follows:

- (1)

- Breaking down state boundaries and generating conditions for civil war are described as “Destabilizing Taghut”, or idolatry. Highlighting the consistency of the ISIS approach with the historical precedent set by AQI, Dabiq credits Zarqawi with having largely accomplished this requirement prior to the present season of warfare.

- (2)

- Establishing the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham as an Islamic Emirate corresponds with the phase of Tamkin, or consolidation.

- (3)

- Bringing like-minded people to fight and live within the Emirate corresponds with the phase of Hijrah, or emigration, which is described as the first phase. Pragmatically, it is a continuous requirement for ISIS rather than a sequential phase.

- (4)

- ISIS has expressed its expansive intent and vision for how it will interact with the rest of the Muslim world by declaring the Khalifa, or caliphate, which ISIS describes as the final-phase objective.

2.4.1. Military Victories

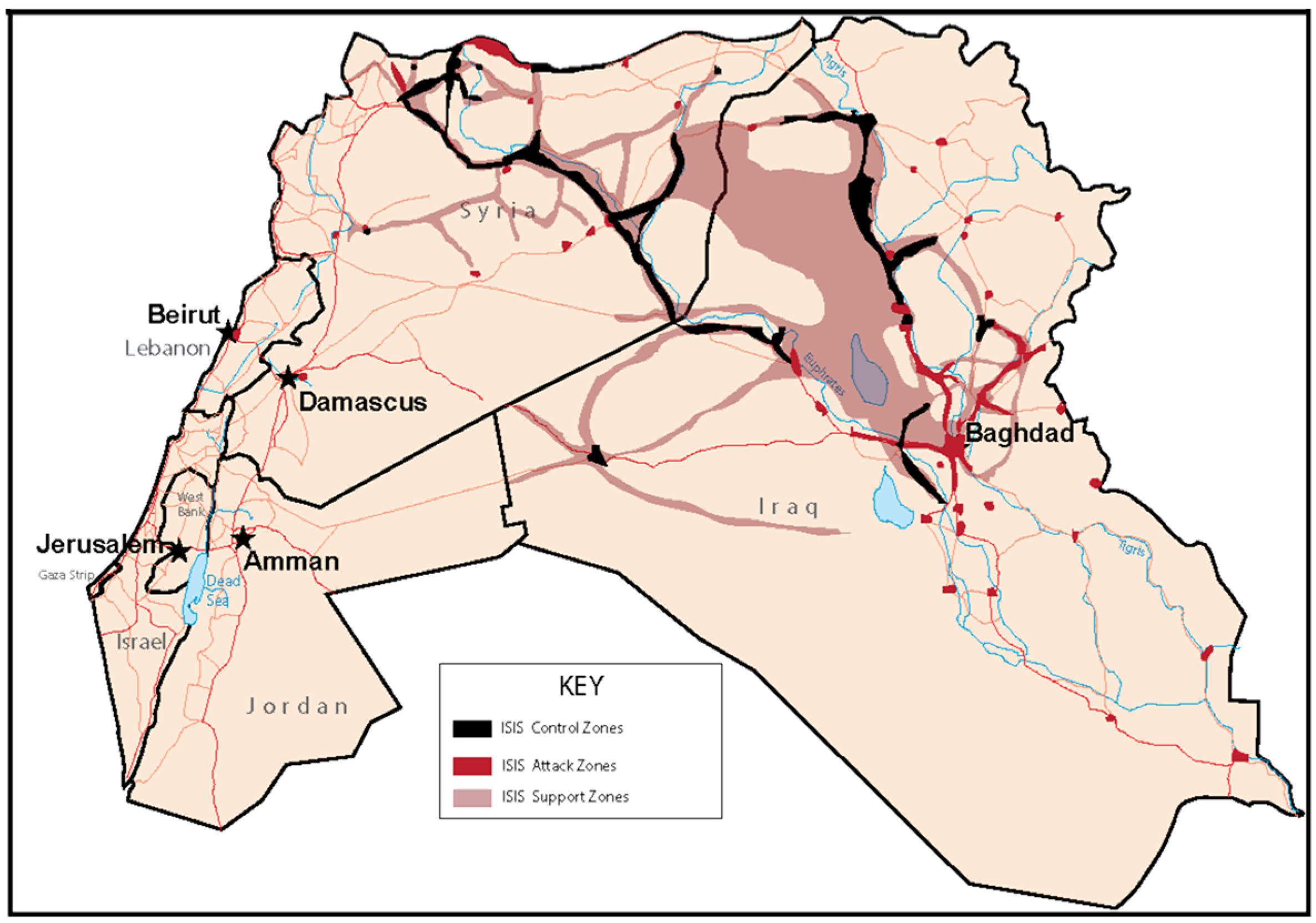

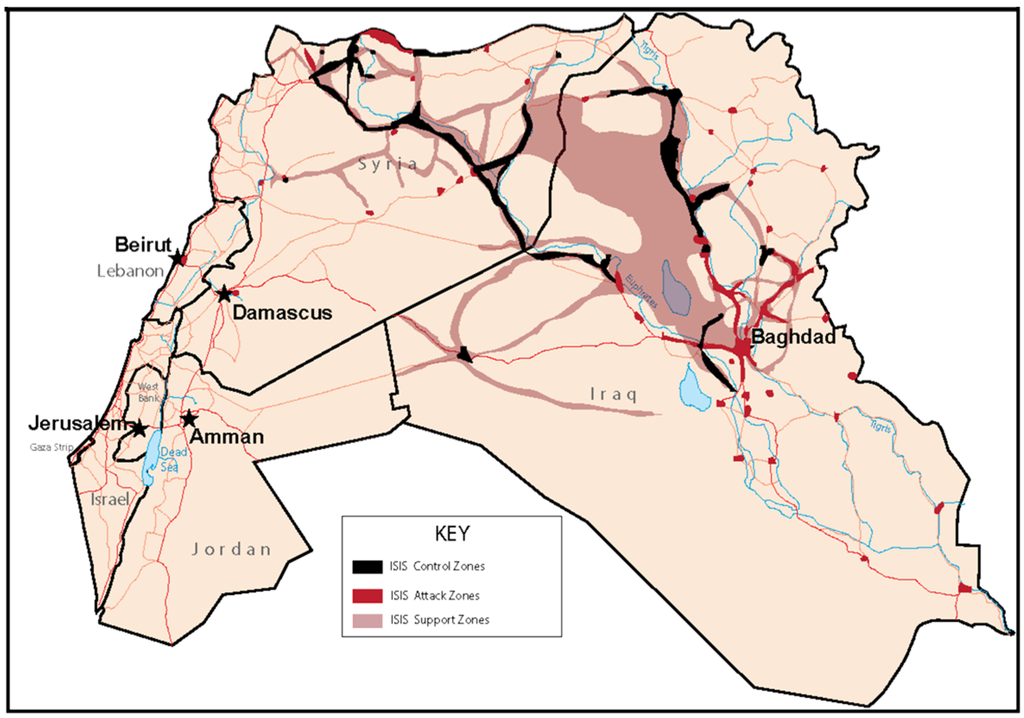

Referencing Figure 1, “since ISIS attacked and established control of Mosul on 10 June 2014, ISIS has prosecuted an extensive urban campaign in Iraq, including cities within Kirkuk, Salah ad-Din, Diyala, and Anbar provinces” [20]. ISIS extended this campaign to include major Syrian cities such as Deir ez-Zour and key terrain along the Syrian-Turkish border, including Ayn al Arab [21,22,23], establishing an effective “ISIS sanctuary” as depicted [24].

Figure 1.

IS sanctuary as of 28 July 2014 [20].

2.4.2. Civil Governance

In the Raqqa and Aleppo provinces in Syria, ISIS has demonstrated over time the ability to sustain control of urban centers by establishing local religious police forces, implementation of Shari’a law, religious schools, reconstruction projects, and food distribution [25]. ISIS control of urban centers is also based upon its ability to keep urban systems running, which is enhanced by the acquisition of a wide array of technical skills through immigration or coercion ([6], p. 13).

3. Approaches to Dealing with ISIS

3.1. Current U.S. Strategy

ISIS requires continued military success, alliances, combat service support, and religious authority. The denial of one of these should at least disrupt the ability of ISIS to proceed with its present strategy [26]. Currently, the strategy of the U.S. comprises assisting the Iraqi government with supporting the formation of Sunni National Guard units that will fight ISIS, with roughly 3000 troops training the Iraqi Security Forces, and with air strikes to support Iraqi ground operations ([6], p. 18). That does not include American warfighting intervention via the redeployment of ground forces to Iraq and civil interventions.

3.2. American Warfighting Intervention

Contemplating the option of American forces deploying to once again secure peace, recall the fight against al-Qaeda in Iraq required 130,000 American troops, almost 90,000 Sunni tribesmen and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi security forces.

3.3. Opinions and Preferences of the Gulf Cooperation Council

The Center for Naval Analysis (CNA) organized a forum to encourage dialogue between the United States and its Gulf allies to explore the broader questions of deterrence and assurance. At this dialogue, a Kuwaiti political scientist gave a talk, the thrust of which was that the United States destabilized the Middle East by allowing the ascendancy of Iraqi Shiites in post-Saddam Iraq. The fall of Saddam “ended the [regional] balance of power with Iran.” All problems in the region stem from this, he argued ([6], p. 18). A senior Saudi diplomatic scholar emphasized that the United States does not understand the values and concerns of its Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) partners. “Does the U.S. recognize Arab needs?” he asked rhetorically [27]. Furthermore, he continued, “the GCC decided to take action against the Houthis in Yemen themselves”. He saw the mission against the Houthis as an assertion of GCC unity, something that made the member states were “very proud.” He called the conflict between Sunnis and Shias in the region to be the biggest threat to security and stability. Agreeing with the senior Saudi scholar, a senior Qatari academic postulated that the “only solution to ISIS” must come from a joint Sunni Arab military force [28]. Finally, several participants commented on the issue of sectarianism. Many agreed that sectarianism is a major threat to the region, and all but three participants (an Omani official, a Saudi journalist, and a Kuwaiti academic) thought that the policies of Middle East states had the main role in the rise of sectarianism. These attitudes of Gulf states foreshadow Gulf states’ leadership towards stability in the Gulf, which is to be discussed in the next section. Such leadership hints that the current American strategy could be successfully coming to fruition.

4. Status of Current American Strategic Successes

Current American strategic successes are best indicated by the examination of ISIS military losses, with the continued rejection of ISIS religious legitimacy emerging from Gulf states’ leadership towards stability in the Gulf.

4.1. ISIS Military Losses

Kurdish forces supported by American airpower retook Mahmour and Gweyr ([28], p. 12); following shortly afterwards, Iraqi forces aided by the Kurds and American airpower recaptured the Mosul Dam ([28], p. 14) and the Haditha Dam [29]. In March 2015, “Surrounded ISIS militants used tunnels to evade Iraqi forces and gain access to Highway 1. The highway is a critical supply route to Mosul, ISIS’ major base in Iraq” [30]. In addition, in April ISIS lost Tikrit [31] to Iraqi forces. Following successful offensives in Ramadi [32] and Allepo [33], Kurdish militias and Syrian rebels seized two strategic towns controlled by ISIS near the border with Turkey [34]. ISIS responded to its losses at the hand of local armies in an offensive [35] which was quickly answered by American airpower [36] and an offensive by the Iraqi army into Anbar [37] followed by Ramadi [38]. In July 2015 these successes by local ground forces were joined by the Turkish air force [39], reinforcing the notion that American military intervention, especially on the ground, is not strictly required to maintain peace in the Middle East. Afterwards, in November, “Kurdish and Yazidi fighters, backed by American air power, began a major offensive to retake Sinjar, Iraq, and cut a crucial Islamic State supply route between Raqqa, Syria, the group’s capital, and Mosul, the largest Islamic State-controlled city in Iraq,” [40] implying that ISIS has lost offensive momentum, a notion that was quickly reinforced by the loss of Sinjar by ISIS to the Kurds [41]. Just a few weeks ago, the momentum continued away from ISIS as the Iraqi army retook the government complex in central Ramadi [42]. In addition to the victories of the local regular armies, Shia militias have also demonstrated both the willingness and capability to fight the Islamic State [43].

4.2. Continued Rejection of ISIS Religious Legitimacy

Gulf states are arguably polarized in alignment between Saudi Arabia, representing the interest of the Sunnis, and Iran, representing the interests of the Shia. Those two major belief systems already fight for religious legitimacy, with Iran contending that only a blood-descendent of Mohammed can lead the religion, while Saudi Arabia and the Sunnis contending that the leader can be elected from among the esteemed clergy. In this context, and knowledgeable of the hundreds of years of bloodshed resulting from neither side’s capitulation, it is nearly unfathomable that the Muslim world would suddenly decide that both Sunni and Shia are wrong, and a violent movement such as ISIS is the right choice of leadership. Instead, it seems more likely that the common threat of ISIS would unify at least the Gulf states.

4.3. Gulf States’ Leadership towards Stability in the Gulf

Several Gulf States have already set aside old animosities to joining forces against ISIS. The New York Times describes, “From information and leaks, we know that they decided to create a joint force to confront the new challenge from ISIS in Iraq and in Syria and to control the tension emerging from Libya and Yemen” [44]. The initial formation of the team of Gulf states was quickly joined, as 34 largely Muslim nations joined the team: “In addition to Saudi Arabia, the coalition will include Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Benin, Turkey, Chad, Togo, Tunisia, Djibouti, Senegal, Sudan, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Gabon, Guinea, the Palestinians, Comoros, Qatar, Cote d’Ivoire, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Maldives, Mali, Malaysia, Egypt, Morocco, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria and Yemen” [45]. Angling towards the strength of ISIS, “combating ideology, involving the use of religious scholars, educators, political leaders and other experts to ’drown out the message of the extremists,” Jubeir said. “This approach will focus on how to deliver effective messages, counter extremist messages and protect youth.”

While Saudia Arabia leads the coalition (not the U.S.), Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir said, “The decisions will be made by individual countries in terms of what to contribute, and when to contribute it, and in what form and shape they would like to make that contribution” [46]. According to Fawaz Gerges, a professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the London School of Economics, “There’s been the idea that ISIS is a bigger challenge for Iran and its allies than it is for the Arab states, even though this feeling is changing now” [47]. According to U.S. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is considering joining Saudi Arabia’s coalition. “We are now exploring the possibility of NATO joining the coalition itself. It would bring unique capabilities, such as the training of ground forces and other capabilities,” [48] he said as recently as 17 February. Although Carter claimed that “we will work with Saudi Arabia to lead Muslim nations to fight terrorism and extremism,” he said that did not include any American boots-on-the-ground planning despite Riyadh’s announcement in early February that it was prepared to do that in Syria. Thus, Middle Eastern countries are willing to fight ISIS without American troops exacerbating the situation.

5. Conclusions

Despite the natural tendency to take stances opposing the status quo, especially in the media, there are at least several indications that the current American strategy is progressing, and perhaps succeeding. The current strategy of the U.S. comprises assisting the Iraqi government support in the formation of the Sunni National Guard units that will fight ISIS, with roughly 3000 troops training the Iraqi Security Forces, and air strikes to support Iraqi ground operations. Recalling that victory over the ISIS predecessor AQI required 130,000 American troops, almost 90,000 Sunni tribesmen and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi security forces, the current American policy clearly presumes that other countries with interest (e.g., neighboring Gulf nations) in Iraq and Syria must step up to the task. Victories by the Kurds and Yazidi, in addition to the Arab states’ endorsement of a broad strategy to stop the flow of fighters and funding to the insurgents and possibly to join military action [48], indicate that the strategy seems to be working. Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon all pledged to stand against terrorism and promised steps including stopping fighters and funding, repudiating the Islamic State group’s ideology, providing humanitarian aid and “as appropriate, joining in the many aspects of a coordinated military campaign” [49]. The Sunni king of Saudi Arabia has clearly joined the fight, having broken up planned Islamic State attacks in the kingdom and arrested more than 400 suspects in a single anti-terrorism sweep, a day after a powerful blast in neighboring Iraq killed more than 100 people in one of the country’s deadliest single attacks since U.S. troops pulled out in 2011 [50]. Saudi Arabia has even committed to sending ground troops [49] if asked by the U.S. and has already sent warplanes to Turkey to fight ISIS [51,52,53], and they have formed a new coalition of Arab countries hinting quite strongly that the U.S. strategy is progressing without a compelling need for an increased American military intervention.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Al Hayat Media Center. “This is the Promise of Allah.” 29 July 2014. Available online: http://myreader.toile-libre.org/uploads/My_53b039f00cb03.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Charles Caris. “The Islamic State Announces a Caliphate.” 30 June 2014. Available online: http://iswiraq.blogspot.com/2014/06/the-islamic-state-announcescaliphate.html (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- SITE Intelligence Group. “ISIL Spokesman responds to accusations and announces a new military campaign.” Translated to English. 30 July 2014. Available online: http://ent.siteintelgroup.com/Multimedia/isil-spokesmanresponds-to-accusations-announces-military-campaign.html (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Mary Habeck. “Attacking America: Al-Qaeda’s Grand Strategy in its War with the World.” Foreign Policy Research Institute. February 2014. Available online: http://www.fpri.org/article/2014/02/attacking-america-al-qaedas-grand-strategy-in-its-war-with-the-world/ (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- House Foreign Affairs Committee testimony on 23 July 2014.

- Jessica D. Lewis. “The Islamic State: A Counter-Strategy for a Counter-State.” Middle East Security Report 21; Washington, DC, USA: Institute for the Study of War, July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- James E. Kelly. “Not Our Fight Alone: An Analysis of the US Strategy Combating the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.” 2015. Available online: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1036 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Ed Husain. “Saudis Must Stop Exporting Extremism.” The New York Times, 22 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce Livesey. “The Salafist Movement.” Frontline. 25 January 2005. Available online: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/front/special/sala.html (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Joe Mintz. “How the Sunni-Shiite Conflict Frames the Current Crisis in Iraq.” International Business Times, 26 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan Gonzalez. The Sunni-Shia Conflict: Understanding Sectarian Violence in the Middle East. Mission Viejo: Nortia Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan Gonzalez. “The Sunni-Shia Conflict in Iraq.” Huffington Post. 18 March 2010. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/nathan-gonzalez/the-sunni-shia-conflict-i_b_384380.html (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Thomas E. Ricks. Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. New York: Penguin Press, 2006, p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Najim Abed Al-Jabouri, and Sterling Jensen. “The Iraqi and AQI Roles in the Sunni Awakening.” January 2010. Available online: http://cco.ndu.edu/Portals/96/Documents/prism/prism_2-1/Prism_3-18_Al-Jabouri_Jensen.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Anthony Cordesman. Iraq’s Insurgency and the Road to Civil Conflict. Westport: Praeger Security International, 2008, p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Wilbanks, and Efraim Karsh. “How the Sons of Iraq Stabilized Iraq.” The Middle East Quarterly 17 (2010): 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Smith. “The Rise of ISIS.” PBS Frontline. 28 October 2014. Available online: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/film/rise-of-isis/ (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Charles Tilly. “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime.” Center for Research on Social Organization Working Paper No. 256; Ann Arbor, MI, USA: University of Michigan, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Harleen K. Gambhir. “Backgrounder.” Institute for the Study of War. 15 August 2014. Available online: http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Dabiq%20Backgrounder_Harleen%20Final.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Emily Anagnostos. “Description of Sitrep and Control Map Series.” Available online: http://www.iswiraq.blogspot.com (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Jenny Cafarella. “ISIS Advances in Deir ez-Zour.” ISW. 5 July 2014. Available online: http://iswsyria.blogspot.com/2014/07/isis-advances-in-deir-ez-zour.html (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- “The Syrian Observatory of Human Rights published content related to escalation of ISIS attacks in the vicinity of Ayn al Arab in the following Facebook posts on 18 July 2014.” Available online: https://www.facebook.com/syriahroe/posts/556648054443537 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- “The Syrian Observatory of Human Rights published content related to escalation of ISIS attacks in the vicinity of Ayn al Arab in the following Facebook posts on 21 July 2014.” Available online: https://www.facebook.com/syriahroe/posts/556724357769240 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- “The Syrian Observatory of Human Rights published content related to escalation of ISIS attacks in the vicinity of Ayn al Arab in the following Facebook posts on 22 July 2014.” Available online: https://www.facebook.com/syriahroe/posts/558173150957694 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- “The Syrian Observatory of Human Rights published content related to escalation of ISIS attacks in the vicinity of Ayn al Arab in the following Facebook posts on 22 July 2014.” Available online: https://www.facebook.com/syriahroe/posts/558444107597265 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Charles Caris, and Sam Reynolds. “ISIS Governance in Syria.” Institute for the Study of War. July 2014. Available online: http://www.understandingwar.org/report/isis-governance-syria (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Barack Obama. “Statement by the President on ISIL.” 10 September 2014. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/10/statement-president-isil-1 (accessed on 28 July 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Afshon Ostovar. “Deterrence and the Future of U.S.-GCC Defense Cooperation: A Strategic Dialogue Event.” CAN Analysis and Solutions Report; Monterey, CA, USA: Naval Postgraduate School, July 2015, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Liz Sly. “Exodus from the mountain: Yazidis flood into Iraq following U.S. airstrikes.” The Washington Post. 10 August 2014. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/exodus-from-the-mountain-yazidis-flood-into-iraq-following-us-airstrikes/2014/08/10/f8349f2a-04da-4d60–98ef-85fe66c82002_story.html (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Anna Coren, Jomana Karadsheh, and Faith Karimi. “U.S. warplanes, Kurdish forces pound ISIS targets in bid to retake Iraqi dam.” 18 August 2014. Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2014/08/17/world/meast/iraq-crisis/ (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Sarah Almukhtar, Natasha Perkel, Tse Achiel, and Youri Karen. “Where ISIS is Gaining Control in Iraq and Syria.” The New York Times. 11 June 2014. Available online at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/11/world/middleeast/isis-control-map.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “The Front Line between ISIS and Iraqi Forces in Tikrit.” 30 March 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “Despite Tikrit Loss, ISIS Still Holds Large Swaths of Iraq.” 7 April 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “How ISIS Captured Ramadi.” 23 May 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “ISIS Advances Toward Aleppo.” 2 June 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “ISIS Loses Two Towns to Kurds and Syrian Rebels.” 23 June 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “New ISIS Offensive in Syria Counters Losses.” 30 June 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “Air Campaign Against ISIS Intensifies.” 8 July 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “A New Offensive against ISIS in Anbar.” 13 July 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “Anbar Offensive against ISIS Shifts to Ramadi.” 23 July 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “Turkey Agrees to Assist U.S. with Airstrikes Against ISIS.” 27 July 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “Kurds and U.S. Launch Operation to Cut ISIS Route.” 11 November 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “How Kurds Captured Sinjar From ISIS.” 13 November 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- The New York Times. “Efforts to stem the rise of the Islamic State.” 28 December 2015. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/06/12/world/middleeast/the-iraq-isis-conflict-in-maps-photos-and-video.html?_r=0 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Janine Giovanni. “Nemesis: The Shadowy Iranian Training Shia Militias in Iraq.” Newsweek, 1 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Micah Halpern. “Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Egypt Unify to Battle ISIS—Is Iran Next? ” Observer. 6 March 2015. Available online: http://observer.com/2015/03/saudi-arabia-jordan-and-egypt-unify-to-battle-isis-is-iran-next/ (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Jack Maddox, Nick Thompson, and Catherine E. Shoichet. “Muslim nations vow to fight Islamic extremism.” CNN. 22 December 2015. Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2015/12/14/middleeast/islamic-coalition-isis-saudi-arabia/ (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Ed Payne, and Salma Abdelaziz. “Muslim nations form coalition to fight terror, call Islamic extremism ‘disease’.” Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2015/12/14/middleeast/islamic-coalition-isis-saudi-arabia/ (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Brooks Tigner. “Counter-IS nations approve military plan and pledge support.” IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly, 17 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lara Jakes, and Adam Schreck. “America’s Arab Allies Vow to ‘Do Their Share’ In Fight against ISIS.” Huffington Post, 11 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huffington Post. “Saudi Arabia Says Thwarts ISIS Attacks, Hundreds Arrested.” 11 September 2014. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/saudi-arabia-isis-attacks_us_55aa5262e4b065dfe89e8490 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Alexander Decina. “Saudi Troops to Syria? Whoa. Bad Idea! ” The Daily Beast. 16 February 2016. Available online: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/02/16/saudi-troops-to-syria-whoa-bad-idea.html (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Ahmed Tolba. “Saudi Arabia Confirms It Has Aircraft in Turkey to Fight ISIS.” Haaretz. 16 February 2016. Available online: http://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/1.703148 (accessed on 28 July 2016).

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).