1. Introduction

Statistics Netherlands (CBS) has recently constructed the Whole Population Network file based on administrative data containing over a billion personal relationships per year among about 17 million inhabitants of the Netherlands (

van der Laan 2022;

van der Laan et al. 2022;

CBS 2023,

2024a,

2024b,

2024c,

2024d,

2024e). These data, referred to as ‘Social Networks’ in further text, include the characterization of the relationships between individuals based on sub-types of ties from the domains of family, work, neighbourhood, schools, and households. Different characterizations represent different network layers and have been derived for each year in the period from 2009 until 2020. Several studies came out recently that assess these data using extensively the network science methods (

Bokányi et al. 2023;

Kazmina et al. 2024;

Menyhért et al. 2024). The Social Networks file itself represents a highly novel and ambitious data infrastructure—praised for its unprecedented scale and analytical promise. It has sparked a growing research agenda and attracted collaboration across Statistics Netherlands (CBS) and multiple Dutch universities (see agenda developed under

https://www.popnet.io/, accessed on 16 October 2025). Despite its appraisal, access to the data remains tightly controlled: only certified researchers operating within secure CBS environments are permitted to work with the microdata, underscoring both its sensitivity and value.

In addition to maintaining this dataset, which is based on registers (“administrative data”), CBS has been conducting and maintaining data based on various surveys of Dutch population. Among these is the yearly Social Cohesion and Well-being (Sociale Samenhang en Welzijn or, in further text “SSW”) survey, started in the year 2012, which by 2022 has interrogated 83,667 randomly sampled individuals of over 15 years of age, as a representative sample of the Dutch population. The survey covers topics related to social contacts, volunteering, involvement in associations, political participation, generalized trust, trust in public, private and political institutions and many other aspects concerning social cohesion, including individuals’ subjective well-being. The SSW has been the basis for many scientific studies on various topics, such as social capital, religion, political participation, trust, volunteering, subjective well-being, the use of language and organ donation (

Schmeets and te Riele 2014;

Schmeets and Peters 2021;

Schmeets 2022;

Schmeets and Cornips 2023—to name only a few), as well as for numerous reports published by the Statistics Netherlands (see

https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/society, accessed on 16 October 2025).

In this study, we introduce the merged Social Networks and SSW dataset and present several high-level findings derived from integrating network-scientific and statistical methods. While this integration alone constitutes a major infrastructural advance, it also prompts a fundamental empirical question: to what extent do the structural properties of individuals’ relational embeddedness—as observed in administrative network data—align with their self-reported behaviours and traits? Specifically, we focus on the basic network measures available from the Social Networks file as a possible empirical bridge between formal relational structures and individuals’ attitudes and actual behaviour related to social capital.

The idea that structural network position shapes access to information, support, or influence is deeply rooted in classical and contemporary social theory. From

Bourdieu’s (

1986) conception of social capital as access to actual or potential resources embedded in durable networks, to

Putnam’s (

2000) articulation of social capital as trust and norms arising from connectedness, relational structure has long been viewed as a generator of social advantage and cohesion.

Granovetter’s (

1973,

1983) work on weak and strong ties and network structure further emphasized that both the number and the type of social connections matter—offering a foundation for linking quantifiable metrics such as degree centrality to broader outcomes like trust and participation. Yet, most prior studies drawing on these theories have relied on egocentric, recall-based survey data or small-scale snowball samples—rather than population-wide, register-based networks such as those employed here.

In this sense, the study does not merely ask whether network centrality is related to social capital, but rather interrogates the validity and utility of a new kind of data abstraction: can highly formalized, observationally derived metrics such as degree centrality meaningfully represent the types of relational structures theorized to underlie social capital? This question is especially relevant in domains such as policy monitoring, where scalable metrics are increasingly adopted in place of costly and difficult-to-administer surveys.

Our aim is thus twofold: first, to empirically examine whether simple structural metrics such as degree centrality—measured across five network layers—are associated with behavioural and attitudinal indicators of social capital collected via the SSW survey; and second, to explore the broader implications of these associations (or lack thereof) for both sociological theory and applied measurement. This includes reflection on what weak associations between structure and behaviour may reveal—whether they stem from limitations of the metrics themselves, mismatches in data design, or more profound conceptual disjunctions in how social cohesion manifests.

The structure of the paper proceeds from this motivation: we begin by elaborating the theoretical basis for connecting social capital with network structure, then introduce the combined dataset and our operationalization of network centrality and cohesion. Analyses proceed from simple correlations to logistic regressions focusing on contact behaviours, with interpretive emphasis on effect sizes and limitations of inference. Rather than positioning the paper as a test of one discrete hypothesis, we offer it as a benchmark and critical reflection on how newly emerging data infrastructures can—and perhaps cannot—capture meaningful aspects of social life.

Links Between Social Capital and Social Networks Research

Social capital remains a highly fluid and contested concept. Despite its widespread use across the social sciences, no consensus exists regarding its precise definition, theoretical underpinnings, or measurement. Still, at its core lies the notion of networks—social capital is most commonly understood as value derived from social relationships.

One of the key early formulations comes from

Coleman (

1988), who conceptualized social capital through within-family and broader community ties. He emphasized the value of closed networks—systems in which individuals are embedded in multiple, redundant relationships—which are analogue to concepts like network closure and clustering. Trustworthiness and the fulfilment of obligations are central mechanisms in his view, reflecting a structure of social norms and enforceable trust. These ideas are closely tied to embeddedness and to the distinction between strong and weak ties (

Granovetter 1973).

Burt (

1992,

2005) builds on this by shifting attention from closure to brokerage. His concept of structural holes—gaps between otherwise unconnected parts of a network—underpins the idea that individuals can benefit from occupying brokerage positions, which allows them to access non-redundant information, to mediate between disconnected others, and exert control over flows of resources and opportunity. While Burt developed specific metrics such as network constraint and effective size, the concept of brokerage aligns closely with betweenness centrality—a measure of how often an individual appears on the shortest path between other individuals (

Freeman 1977).

Lin (

2001) adds a status-sensitive dimension to social capital. He defines it as access to, and mobilization of, resources embedded in social ties, with the key insight that the value of a tie depends on the influence or status of the connected alter. This introduces a hierarchical logic: advantage comes not just from having ties, but from who those ties lead to. This concept parallels recursive centrality measures like PageRank (

Brin and Page 1998) and HITS (

Kleinberg 1999), where an individual’s importance derives from whether it is connected to already well-connected individuals. Betweenness centrality also fits this framing, reinforcing the analytical connections between Lin’s theory and Burt’s structural focus.

Portes (

1998) anchors the structural understanding of social capital by framing it as the capacity to access resources through embeddedness in social structures. While he does not use formal network metrics, the mechanisms he emphasizes—such as obligations, expectations, and information flows—are rooted in patterns of relational embeddedness that can, in principle, be examined through structural properties like network density, redundancy, or tie configuration. Rather than offering a formalized model, Portes argues for a theoretically grounded, mechanism-based analysis of social structures—a direction that network science complements but does not fully exhaust.

This more traditional formulation of social capital complements another strand in the literature: one that connects social capital to social cohesion, and in doing so, arguably extends the concept to encompass the collective dimensions that Portes alludes to. In this view, social capital is understood as both a building block and an indicator of social cohesion—emphasizing civic engagement, generalized trust, and shared norms and values (

Berger-Schmitt 2002;

Chan et al. 2006;

Schiefer and Van der Noll 2017;

Moustakas 2023;

Tok et al. 2024). This perspective is especially visible in survey-based research, including the SSW dataset, where social capital is operationalized both as an individual asset that facilitates social cohesion, well-being and economic productivity. Here, Resource Theory (

Bourdieu 1986) provides a theoretical backbone: individuals with greater social, economic, and cultural capital are better positioned to form and maintain beneficial ties. These resources increase one’s potential to engage in social life.

As part of the social cohesion strand of research, social capital is conceptualized both as a community-level asset (

Neira et al. 2009) and as an individual attribute (

Gannon and Roberts 2020). A widely cited definition from the OECD captures this dual nature: “networks, together with shared norms, values and understandings, that facilitate cooperation within or among groups” (

OECD 2001, p. 41; see also

Keeley 2007). This framing stresses the collective dimension of social ties as the basis for mutual understanding and cooperation.

Beyond these classical formulations, recent comparative work has further broadened the conceptualization of social cohesion and its empirical assessment. A notable example is the Bertelsmann Social Cohesion Radar (

Bertelsmann Stiftung 2013;

Dragolov et al. 2016), which advances a multidimensional framework encompassing social relations, connectedness, and orientation toward the common good. These domains are operationalized through a comprehensive set of attitudinal and behavioural indicators, including trust, participation, institutional confidence, and perceptions of fairness. Although the Radar is derived entirely from survey data—and thus differs from our structurally oriented, register-based approach—it reinforces the view that social cohesion is inherently composite and cannot be captured through any single behavioural or relational measure. The framework also highlights that social capital, particularly in its participatory and trust-based components, constitutes a core pillar of cohesion. In this sense, the present study contributes to this broader research agenda by examining how administratively observed patterns of relational embeddedness correspond to self-reported elements of social capital within a national survey framework.

Yet operationalizing all these concepts—particularly in quantitative terms—poses great challenges. Surveys often rely on proxies such as generalized trust or volunteering, or composite indices that aggregate multiple indicators of participation and social perception (

Putnam 2000;

van Beuningen and Schmeets 2013). While this approach captures important qualitative aspects of social connectedness, it lacks precision on the structural side. Contemporary network science offers a complementary toolkit, enabling the measurement of how individuals are connected, embedded, or structurally advantaged within relational systems.

Bringing these perspectives together allows for a more comprehensive view of social capital—examining both the qualitative content of relationships and the structural patterns in which those relationships are embedded. Ties between individuals—whether kin, neighbours, colleagues, or housemates—can be counted, mapped, and linked to known behaviours and outcomes. This dual lens supports a richer analysis of how social structures contribute to individual well-being and collective cohesion.

In the following sections, we work with what is available: the best possible approximations of social capital components, given the structure and limitations of the data. As should be clear from the preceding discussion, operationalizing social capital is always a function of what can be observed and measured—not just what can be theorized. The indicators used in the definition and analysis are grounded in this constraint. What we present is not a comprehensive capture of the concept, but a data-driven, theory-informed approximation. For details on how each component is constructed, interpreted, and used in the analysis, see the subsequent chapters—where every indicator is defined as clearly and transparently as the data allow.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. SSW Dataset and the Derived Indicators

Conducted annually by Statistics Netherlands (CBS) since 2009, the SSW survey serves as a nationally representative instrument for measuring self-reported social attitudes, behaviours, and perceptions. Eligibility criteria are clearly defined: individuals must be aged 15 or older and registered in the Dutch population register (BRP) as of the first day of the survey month. Those living in institutional settings (e.g., care facilities, correctional institutions) are excluded from the sampling frame. Respondents are selected through stratified random sampling to ensure coverage across key sociodemographic strata, including age, gender, region, and migration background. Responses have been gathered via a sequential mixed-mode design: internet and, after two unsuccessful reminders, by telephone or face-to-face, with the response rate of about 55 percent. To reduce potential non-response bias, data have been reweighted by population characteristics such as gender, age, household size, migration background, marital status, income, urbanity and region.

Each annual wave aims to achieve approximately 7600 completed responses. The sample size is set by CBS to ensure analytical robustness across both cross-sectional and pooled designs, balancing statistical power with operational feasibility. The present study combines eleven waves of SSW data from 2012 to 2022, comprising more than 83,000 unique respondents and offering extensive leverage for population-level and subgroup analyses.

Regarding missing data, CBS uses standard exclusion rules for cases with invalid contact addresses or administrative anomalies and applies post-stratification weights to adjust for differential nonresponse. For our analysis, cases with missing values on key variables were excluded listwise, and final sample sizes are reported in each analytical section. These procedures ensure that estimates remain generalizable while minimizing bias. For more details on the sampling and the design, one can consult

CBS (

2024f).

In the analysis we rely on the social cohesion framework developed by Statistics Netherlands in 2008. This framework measures social capital along two key dimensions—participation and trust—and, partly based on Putnam’s social capital index (

Putnam 2000), integrates them into a single index (

van Beuningen and Schmeets 2013; see

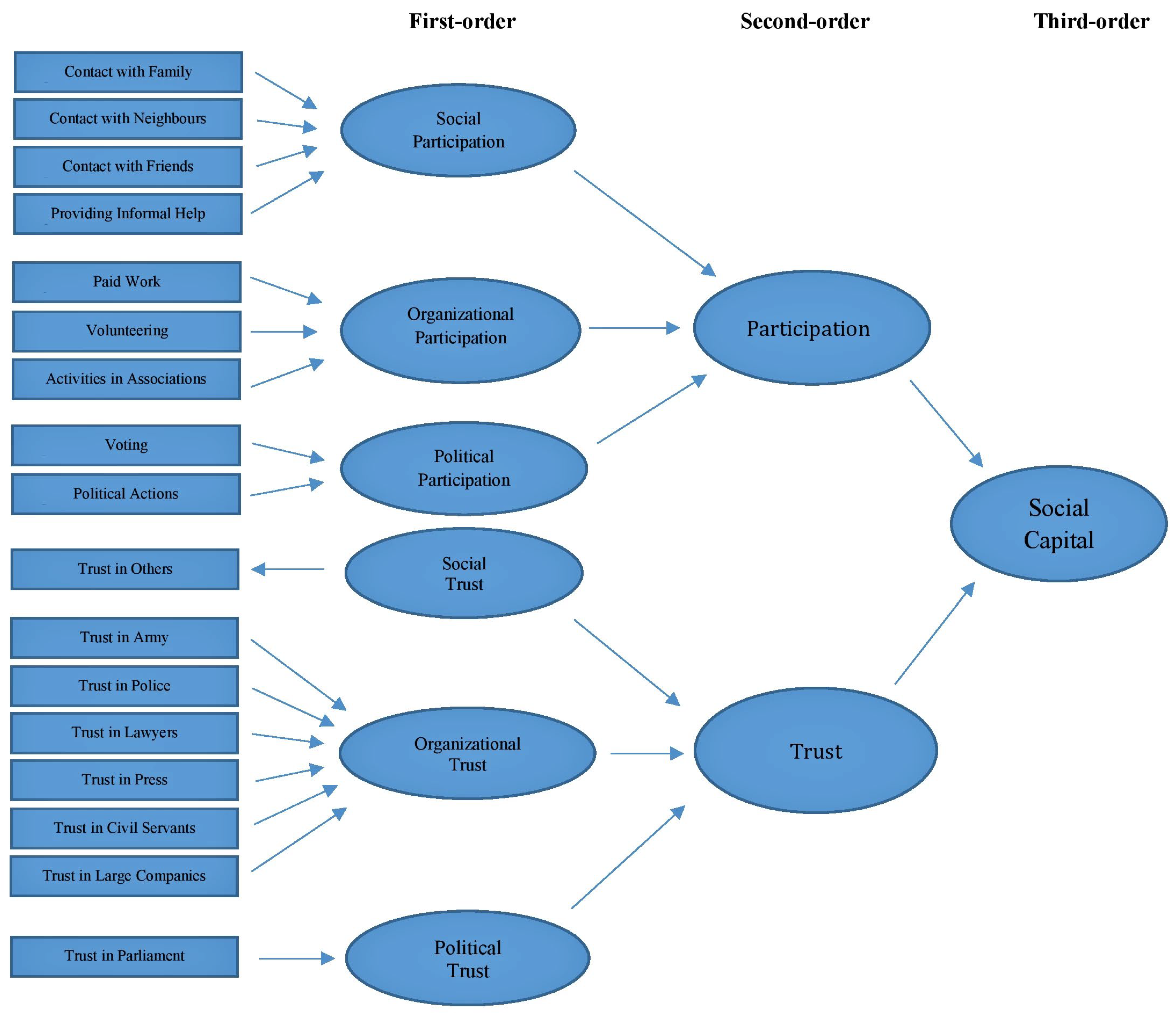

Figure 1).

For each of the participation and trust dimensions, the model makes distinctions at the social (micro), organizational (meso) and political (macro) level (see also

Halpern 2005;

Sharp and Randhawa 2012). On the participation dimension, the social level captures contacts with family, friends and neighbours, and help provided to other people. The organizational level covers volunteering, activities in associations, and paid work, and the political level includes voting in parliamentary elections and participation in other political actions. The trust dimension contains information on trust in other people (social level); trust in the army, police, lawyers, civil servants, media and large companies (organizational level); and trust in parliament (political level). The model thus contains six sub-dimensions, three for participation and trust each, and a total of 17 different indicators. The formative model was identified by Multiple Table Analysis, also called a Hierarchical Components Model (

Lohmöller 1989;

Tenenhaus et al. 2004), and was estimated in R using the PLSPM package (

Bertrand 2024). A path weighting scheme was used so weights can be interpreted as regression coefficients. Weights are calculated from the first order on the two second-order constructs—participation and trust. These, in turn, contribute independently to the social capital index.

The addressed 17 indicators are based on the yearly SSW questionnaires in the period 2012–2022 and will be used in the subsequent analyses and use case demonstrations from our merged file. All indicator values are calculated at the individual level.

Maintaining Contacts. The survey includes three separate questions to respondents on the frequency of contacts with: (i) one or more family members, (ii) friends, partners, or very good acquaintances and (iii) neighbours, each with the scale from 1 (daily) to 5 (rarely or never). Contacts are meetings in-person, phone-calls, letters, or by using social media. From these we have derived the binary indicators of Maintaining Contacts for each of the three segments, where in each case 1 stands for if the contacts are maintained at least once a week, and 0 if otherwise.

Informal Help-Giving. Respondents were asked if they were giving unpaid help to people outside their household, such as the sick, neighbours, family, friends, and acquaintances in the four weeks prior to being surveyed. The one-to-one translation of this binary variable is regarded as an indicator of Informal Help-Giving.

Work participation. Respondents were asked whether they had a paid job for at least 12 h per week. This gives the binary variable.

Volunteering. The survey investigates whether the respondent has volunteered in the 12 months prior to being surveyed. Based on twelve organizations, such as for schools, sport clubs, and health care organizations, a binary variable was created which is regarded as an indicator of Volunteering.

Participation in Associations. Respondents were asked about the frequency of their participation in activities of one or more associations. The newly created binary indicator has values of 1 if the respondent’s participation in activities is at least once per month and 0 if less.

Political Action. A set of nine questions was asked regarding respondents’ engagement in political matters in the 5 years period prior to being interviewed, specifically through (1) participating in media events to exert influence, (2) approaching a political party or organization, (3) taking part in meetings or debates organized by governmental bodies, (4) approaching a politician or official, (5) participating in an action group, (6) participating in a protest action, protest march or demonstration, (7) participating in a paper or internet signature campaign, (8) taking part in a political discussion or action on the internet, and (9) making some other (unlisted) political action. The binary indicator of Political Action has a value of 1 if the respondent engaged in at least one of the actions.

Voting Participation. Respondents were asked whether they voted in the most recent Dutch parliamentary elections in 2010, 2012, 2017, or 2021, depending on the date the question was answered. The derived binary indicator of Voting Participation takes a value of 0 (not voted) and 1 (voted).

Social trust. The survey asked about the person’s trust in other people, in general, based on two answer options: (0) you cannot be too careful when dealing with other people or (1) most people can be trusted.

Trust in institutions. The survey inquired about trust in: (1) judges, (2) police, (3) the army, (4) the press, (5) civil servants, (6) large companies, and (7) parliament, with the answering scale ranging from 1 to 4, where 1 and 2 stand for highly and quite trustful, respectively, and 3 and 4 stand for little and no trust, respectively. From these questions, we have created binary indicators of Trust in Institutions for each category with a value of 1 if the respondent shows any trust (answering 1 or 2 to the original question), and 0 otherwise.

2.2. Social Network Data and the Derived Indicators

Before introducing the network indicators used in the analysis, we first outline the network abstractions which form the basis for their calculation. The “Person Network of the Netherlands” (

Persoonsnetwerk) maintained by CBS is constructed from a series of relational network files that infer person-to-person connections from administrative registers. These files form part an integrated dataset initiated by

van der Laan (

2022) and

van der Laan et al. (

2022) and subsequently revised in 2023 to enhance consistency and coverage across network layers (

CBS 2023). The version used in this study reflects the most recent CBS release, which includes corrections and structural changes to the earlier design (see the aforementioned reference for details). In each network, the nodes represent individuals in the Dutch resident population, and links are defined based on family, neighbourhood, workplace, educational, or household relations. The current version of these relational abstractions enables consistent, full-population coverage, providing the foundation for calculating network metrics such as degree centrality.

It is important to note, however, that we do not have access to the full network layers. Instead, we received for our analysis, primarily due to confidentiality reasons, only the direct ties of the SSW respondents. As a result, researchers like us working under these conditions cannot compute full-network metrics, multi-step path-based measures, or institution-level denominators and then merge them back onto the sample. The only feasible and methodologically appropriate approach is to work with the respondent-level slices of each network layer as provided. The following paragraphs describe the original logic used in constructing each network layer, with references to the corresponding documentation for each, which is followed by deeper discussion on limitations due to not having the full dataset.

Family Layer. The

Familienetwerk (

CBS 2024c) links individuals based on official kinship relations, as documented in the Dutch municipal personal records data base (Basisregistratie Personen, BRP) and historical registries. The network captures a broad definition of family, encompassing biological and adoptive relationships (e.g., parent, child, full and half siblings, grandparent, cousin), legal relationships (e.g., spouse, registered partner, stepparent, stepchild), and in-laws (e.g., parent-in-law, sibling-in-law, cousin-in-law). Individuals are linked to nuclear family members, partners, the family of those partners, and members of stepfamilies. These links are binary and undirected and reflect formal family structures registered administratively, without weighing for relational closeness.

Neighbour Layer. The

Burennetwerk (

CBS 2024a) contains two conceptually distinct proximity-based tie definitions, both derived from BRP registration and BAG address data. First, a “neighbour” is defined as any person living at one of the ten physically closest addresses to an individual’s home. There is no maximum distance threshold; the closest addresses are selected regardless of how far they are. All individuals residing at these addresses are linked. In cases where multiple addresses are equidistant at the 10-address cutoff, selection is randomized. Second, a “neighbourhood resident” is any individual living within a 200 m radius around the focal person’s address. From this group, up to 20 individuals are randomly selected. If fewer than 20 individuals fall within the radius, all are included. Links in both cases are binary, undirected, and based purely on spatial proximity rather than behavioural interaction.

Colleague Layer. The

Colleganetwerk (

CBS 2024b) is formed using labour market register data and defines a tie between two individuals who were employed by the same company identified by a shared legal entity identifier (Statutair Bedrijfseenheid ID, or SBEID) during at least one month of the reference year. To manage scale and maintain computational feasibility, if a person had more than 100 potential colleagues in a given year, the 100 geographically closest colleagues (based on residential address) are selected. This method accounts for turnover and variation in colleagues throughout the year. All links are binary and undirected, and reflect shared organizational affiliation, not necessarily interpersonal contact.

Classmate Layer. The

Klasgenotennetwerk (

CBS 2024e) captures educational co-attendance based on monthly enrollment data. A link is created between two individuals if they attended the same educational institution during at least one month of the reference year. This includes students enrolled in primary education, special education, secondary education, vocational schools, universities of applied sciences, and research universities. The resulting ties are binary and undirected, and do not distinguish between levels of engagement or specific class groups—only shared institutional presence during the year is required.

Household Layer. The

Huisgenotennetwerk (

CBS 2024d) is based on BRP data and defines a link between all individuals registered at the same residential address as of 1 January of the reference year. This includes both private households and institutional households (e.g., care homes, student housing). If any individual at an address is registered as living in an institution, then all residents at that address are flagged as institutional housemates. Ties are binary and undirected, reflecting shared domestic living arrangements regardless of the nature of relationships between household members.

The following are the social network indicators we have calculated on the Social Networks datasets, calculated at the respondent level, and merged with the SSW dataset into one file. These indicators are also involved in subsequent analyses and use case demonstrations.

Degree Centrality. We have calculated the degree centrality (

Freeman 1978) of the respondent on the binary undirected network abstraction

1 for each layer for each year, which indicator is essentially the count of the number of family members, work colleagues, neighbours, schoolmates and household members the respondent of the SSW survey has in each of the respective network layers. “Binary undirected” is the basic abstraction in which strength and direction of relationship (e.g., the higher weight for closer relatives, the direction father to son, grandfather to father, etc.) are not considered, only the existence (1) or non-existence (0) of the relationship. (Although weighting ties—particularly within the family layer—would in principle allow for a richer representation of relational proximity, implementing such weights requires a well-defined and theoretically justified weighting scheme. At present, no validated or consensus-based approach exists for assigning relative weights to administratively defined kinship or proximity ties. As discussed in the conclusion, one of the contributions of this paper is to provide empirical insight that may inform future development of such weighted abstractions.) As correlations between any two-yearly degree centrality value sets were consistently close to 1—and because high-level interruptions such as the onset of COVID-19 in early 2020 do not affect administratively defined network ties—we used the 2020 centrality value as the representative measure for each respondent.

Distance-Weighted Degree Centrality. We have calculated two distance-weighted degree centrality measures for each respondent based on kinship ties in the administrative data. For each year, we computed the great-circle (i.e., “direct flight”) distance between the centroid of the respondent’s municipality of residence and the centroid of each relative’s municipality of residence. Centroids were determined using the geographic centre (latitude and longitude) of municipal polygons provided by CBS. The great-circle distances were then calculated using the Haversine formula (

Sinnott 1984).

For each respondent, we derived two indicators based on averaging over the period 2012 (the start of the SSW) to 2022; (i) the average of distances to other family members and (ii) the sum of distances to other family members. These two metrics served as spatially informed proxies of family network dispersion over time, which hypothetically has an impact to maintaining contact with the family members.

Summary statistics for each network layer—such as degree distributions, number of links, average degrees, clustering coefficients, and degree-degree correlations by relationship type—are comprehensively documented in

van der Laan (

2022) and

van der Laan et al. (

2022). Given that our data is a representative sample of the 15+ population in the Netherlands, the distributions in the aforementioned works are directly comparable to ours.

Given the range of possible network measures, it is necessary to explain why the present analysis is limited to these two metrics. The explanation lies in the structural constraints of the available administrative data. While the Person Network offers multiple relational layers, these networks are not fully observed: we only have data on connections involving individuals in the SSW sample. This partial observability makes the application of more complex or global network measures—such as density, composition, range, diversity, closeness and betweenness centrality, homophily, or multiplexity—methodologically problematic. These metrics require complete information on the broader network topology, which is unavailable for most layers and fundamentally distorted for others.

Moreover, the structure of the family network imposes additional limitations. By design, this network is a hierarchical tree; it does not reflect broader interconnectedness beyond immediate kin. Even if full network data were available, the tree structure inherently restricts the use of metrics that assume more complex relational pathways. The same applies to other layers such as neighbours, colleagues, and classmates, where links are only available for direct connections involving SSW respondents. As a result, the broader network structure remains unobserved, reducing each layer to fragmented “ego-networks” or disconnected clusters, rather than cohesive, analyzable graphs. The result is a set of networks where higher-order or directionally sensitive measures would introduce unjustifiable assumptions and likely distort interpretation.

Given these considerations, we restrict our analysis to binary, undirected degree centrality, which is both conceptually clear and technically feasible across all network layers. While more advanced abstractions—such as weighted or directed ties—may offer additional nuance, implementing them requires modelling assumptions that cannot be empirically justified with the current data. Moreover, exploring these extensions rigorously would necessitate a dedicated study beyond the scope of the present analysis. These limitations are acknowledged here and revisited in the concluding chapter as priorities for future research.

3. Results

Here we examine the relationship between individual-level network indicators and key social outcomes, drawing on the combined strengths of administrative and survey data. Before we turn to the main analyses, it is important to clarify how we approached the temporal structure of the data and why longitudinal modelling was not pursued although both the administrative network data and the SSW survey data are collected annually. This decision is motivated by two main considerations.

First, exploratory checks revealed that centrality measures were highly stable across years: correlations between values from any two years were consistently close to 1 (>0.98, Pearson). As a result, we opted to use the centrality values from the year 2020 as a representative snapshot. Second, while the SSW dataset is technically longitudinal, its design is effectively cross-sectional: each year, a new sample of on average 7600 individuals is surveyed, with no overlap across waves. Analyzing these as separate yearly panels would reduce statistical power and risk unstable estimates. By pooling all available waves into a combined sample of 83,667 individuals, we gain the statistical leverage necessary to explore associations between network indicators and survey outcomes at a meaningful scale. Given that this is the first study to integrate nationwide kinship network measures with rich individual-level survey data, we prioritize analytical strength and generalizability over temporal granularity.

To answer our research question—if and how social network centrality relates to social capital—we start by investigating how the 17 social capital indicators as well as the 5 social network centralities differ between subpopulations. From the perspective that higher network centrality will be associated with more individual social capital, we expect to find similar patterns. In a next step we will look at the correlations between the 5 centralities and the social capital composite and the single indicators.

In

Table 1 and

Table 2, we detail general individual attributes—gender, age, level of education, income, and migration background—and their relationship with 17 indicators measuring participation and trust, based on SSW data from 2012 to 2022. These tables serve as descriptive statistics for the variables used in the subsequent analysis and help familiarize the reader with the associations between core demographic characteristics and various elements of social capital. Moreover, these general attributes play a crucial role as control variables in the regression models presented later. The numbers clearly show the variation between all these subpopulations in the levels of participation and trust in Dutch society. More resources, in particular education, results in more participation and trust. Education is also strongly related to the trust indicators. A minority of 40 percent of the group with elementary education say that ‘other people can be trusted’, which gradually increases to 85 percent among the group with a master’s degree. Also, many gender and age differences reveal in participation and trust levels. Females exhibit more contacts with family members and friends and are more prone to informal help-giving than males. Females also often show more trust in institutions but are less trustful to other people than males. Maintaining contacts with friends is more prevalent among younger individuals, whereas maintaining contacts with neighbours is more common among older individuals, which aligns with expectations. Additionally, a larger percentage of elderly individuals participate in voting, and political action declines with age. And, overall, younger age groups trust others and also trust institutions more than elderly do. Likewise, Dutch natives and migrants differ on many participation and trust indicators.

In

Table 3 we present for the same subpopulations the average centrality degrees. Overall, and not in line with the social capital indicators, the subpopulations do not show much variation in the five centrality measures. This is particularly true for the connections with neighbours, ranging from 40 to 45. Males and females exhibit similar levels of family and neighbour connections, but females demonstrate higher work-related connections compared to males. In addition, females show a substantial higher level of connections at schools which indicates that females going into schooling programmes or schools with more attendees than men. Young adults aged 15–24 have high degree centrality in work and school, and they exhibit the highest household connections. Middle-aged individuals, particularly those aged 25–44, show high family connections, with the highest school network connections among those aged 35–44.

As regards the educational levels, there is some trace of association with the degree centrality indicators. University-educated individuals have the highest levels of work-related connections and school network connections. Those with HBO education also exhibit high levels of work and school connections. In contrast, individuals with elementary education levels exhibit the lowest levels of connections across these indicators, particularly in school networks. Income status also plays a significant role in degree centrality. Individuals in the highest income quartile show the highest levels of work-related connections and school network connections. Those in the lowest income quartile exhibit lower levels of connections in these areas, although they have relatively high family and household connections.

Migration background reveals differences in degree centrality indicators as well. Native individuals have higher levels of family connections and similar levels of work connections compared to migrants. Both groups show similar levels of neighbour and school connections. However, migrants exhibit slightly higher household connections compared to natives.

It might be important to note that of the 83,667 respondents, 1249 were identified as having no family connections whatsoever. This sample represents approximately 1.5% of the total respondent pool. Our closer examination of the demographic profile revealed that this group was predominantly composed of first-generation migrants, which appears logical. The group was distributed across age brackets, with the largest proportion being 65+, likely due to deceased relatives or lack of children. There was no significant gender difference, and the majority had low educational attainment, though not overwhelmingly so. These individuals were excluded due to the very high correlations with the controls in the models which would result in high variance inflation factor values, and due to the extremely small size of the group.

3.1. General Associations of Variables

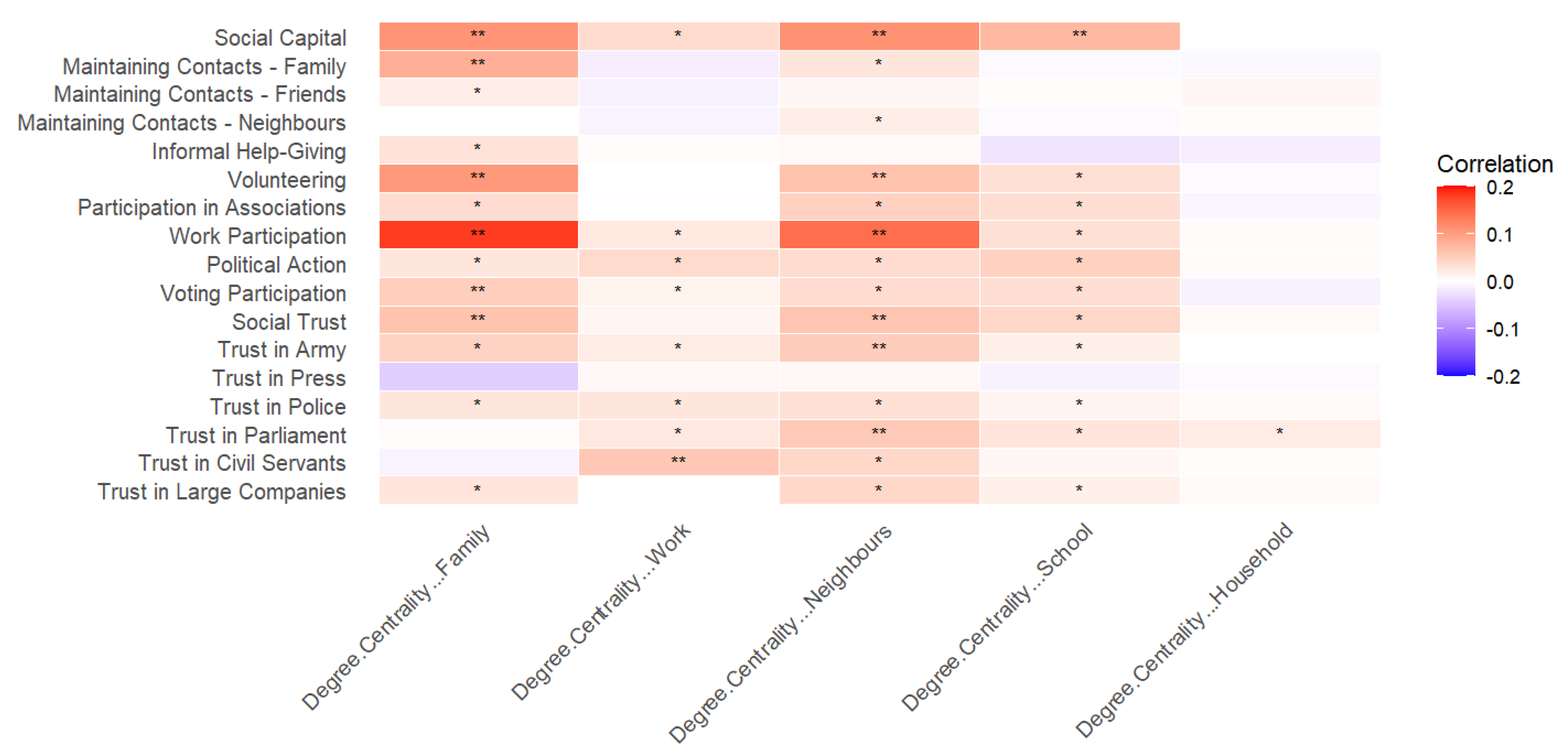

In

Figure 2 we list the correlations between the Social Networks indicators and the social capital composite indicator as well as the 17 specific social capital components. Generally, the correlations are positive and significant, but rather weak and often not reaching the p-value lower than 0.01, as indicated by a single asterisk (*). Essentially, only two centrality measures show higher levels of significancy (

p < 0.01): family and neighbours. However, the connection a person has with its neighbours shows a low correlation (0.12) with social capital, and this is also true for the family networks with social capital (0.11). Unexpectedly, also the correlations between the networks and actual behaviour in terms of contacting family members and neighbours are low. As per other indicators, volunteering, having paid work, and voting in elections show positive correlations with the size of their family, while volunteering and paid work relates to the connections with neighbours.

Interestingly, social trust shows weak positive correlations with family and neighbour degree centrality. Apparently, being surrounded by others fosters trust in other people in general. Trust in the army and in parliament also exhibits weak positive correlations with the neighbour network.

In sum, the associations between any two variables are generally very weak, with most correlations being close to zero. Notably, the strongest observable relationship emerges between the frequency of maintaining contacts within the family and the individual’s actual number of connections in the family network, as indicated by a modest but relatively higher correlation of approximately 0.11. In contrast, there is virtually no association between maintaining contacts with neighbours and the number of neighbours a person has. This absence of association likely reflects the fact that the neighbour layer captures administrative co-residence rather than socially meaningful proximity—particularly in dense or high-rise settings where many neighbours may not be personally known. Moreover, variation in maintaining contact with neighbours during the pandemic years (2020–2022) may have further attenuated this relationship.

Due to unexpectedly low correlations especially between connectivity vs. maintaining contacts in both the family and neighbours category, we took a closer look into these categories using some more refined indicators and transformations. In particular, we have used logarithmic transformation with natural logarithms for degree centrality measures. In network research in general, degree distributions following a power-law distribution are commonly found, where a few nodes have very high degrees, while the majority have lower degrees. For the Social Networks of this dataset, the distributions are not strictly following power law, but this is due to how networks, especially those of neighbours in this case, have been abstracted (see

van der Laan 2022).

In addition to Distance-Weighted Degree Centrality in both layers, as defined in the previous section (both in its original form and logarithmically transformed), we incorporated several other measures. These include the natural logarithm of Degree Centrality, the average geographical (crow fly) distance to all family relatives or neighbours of a person based on registered residence addresses in 2020, and the total sum of these distances. To account for potential scale effects, we also applied logarithmic transformations to both the average and total distance measures. However, all such amendments did not substantially improve the correlations.

3.2. Regressions with (Segment) Control Variables

In the following part of the analysis, we delve into the analyses of specific segments of the populations in terms of their general attributes and main social capital components given their social network embeddedness. We perform a set of logistic regressions with dependent variables Maintaining Contacts with Family and with Neighbours. These, and degree centrality variables were recoded before modelling. The Maintaining Contacts variables were recoded as binary indicators with value 1 for person having contact at least once per week, and 0 otherwise.

Degree Centrality-Family was split into 15 groups. Specifically, we retained the original values for those with 1 to 5 connections. For those with more extensive networks, we grouped the connections into broader categories: 6 through 9 connections were recoded as 6, 10 through 13 as 7, 14 through 17 as 8, 18 through 21 as 9, 22 through 26 as 10, 27 through 31 as 11, 32 through 39 as 12, 40 through 53 as 13, 54 through 66 as 14, and 67 through 364 as 15. Although arbitrary, this recoding process was guided by prior experimentation with strict decile cut-offs, which proved less sensible. Our approach adheres to power law distribution principles typical of networks, where few individuals have many connections and many have few, while recognizing that it is uncommon for individuals to have only 1 or 2 connections, and that family networks deviate from typical network patterns.

As regards the Degree Centrality-Neighbour variable, we found an unusual distribution of the degree centrality values, with a strong frequency peak between 30 and 60. This arises from defining neighbours as the members of a combination of close neighbours and the residents of the closest 10 households within a radius of 200 m (for a detailed definition, consult

CBS 2024b). This method results in many individuals having similar centrality values, especially in densely populated areas or institutions, thus creating the observed distribution anomaly. On average, a person has 43 neighbours (standard deviation = 7.3) with a range from 13 to 182

2. We hence did not stick to the former principle as with family centrality but recoded the neighbour degree variable by partitioning the values based on cut-off points for creating 15 equal groups. All other used variables remained as previously defined. The summaries for both models are provided in

Table 4, while the description of the models is provided in the sequel.

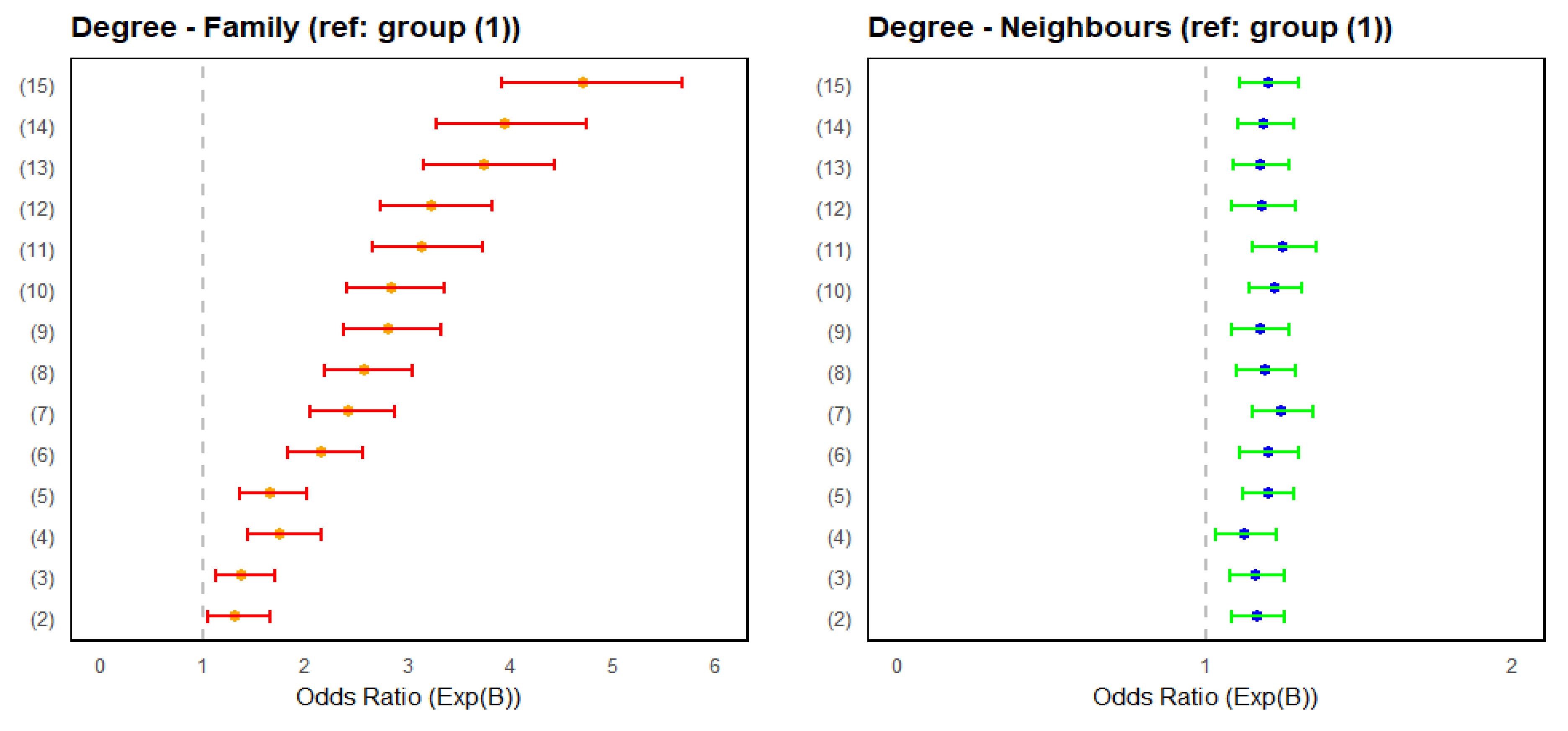

3.2.1. Model 1: Basic Model; Maintaining Contacts vs. Degree Centralities

In Model 1, we explored the relationships between Maintaining Contacts and Degree Centrality variables within the family network and within the network of neighbours in parallel. The overview is provided in

Figure 3 with boxplots capturing relations between the centrality measures and the social contacts (see

Figure 1,

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 4 for all results).

The R Square value (Nagelkerke) for Model(s) 1 suggest that a small percentage of the variance in maintaining social contacts is explained by the degree centrality in the family network, and even less in the neighbourhood network, indicating modest explanatory power (see

Figure 1,

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 4). However, degree centralities add significant contributions, expressed in the overall Wald values for family (~841.4) and neighbours (~50.2). Each increase in family degree centrality significantly raises the likelihood of maintaining family contacts. The odds ratio of the second group with one family connection shows that the chance of having at least once a week a family contact is higher compared to the group with maximum of one connection serving as the reference group. Subsequently the odds ratio’s increase, following almost a linear pattern, to 4.6 for individuals with the highest family degree centrality. This suggests that family networks may contribute to the actual contacts with other family members in-person, phone-calls, letters, or by using social media.

This model shows clearly the importance of an individual’s family network size in predicting the maintenance of family relationships. As for the neighbours domain, the odds ratios for the other than the baseline group differ only slightly from 1.25 to 1.36 without a clear linear pattern. This suggests that the size of the neighbours in a person’s direct environment is only important if the first cut-off point has been reached. Consequently, having more neighbours does not imply more frequently maintaining contacts with them.

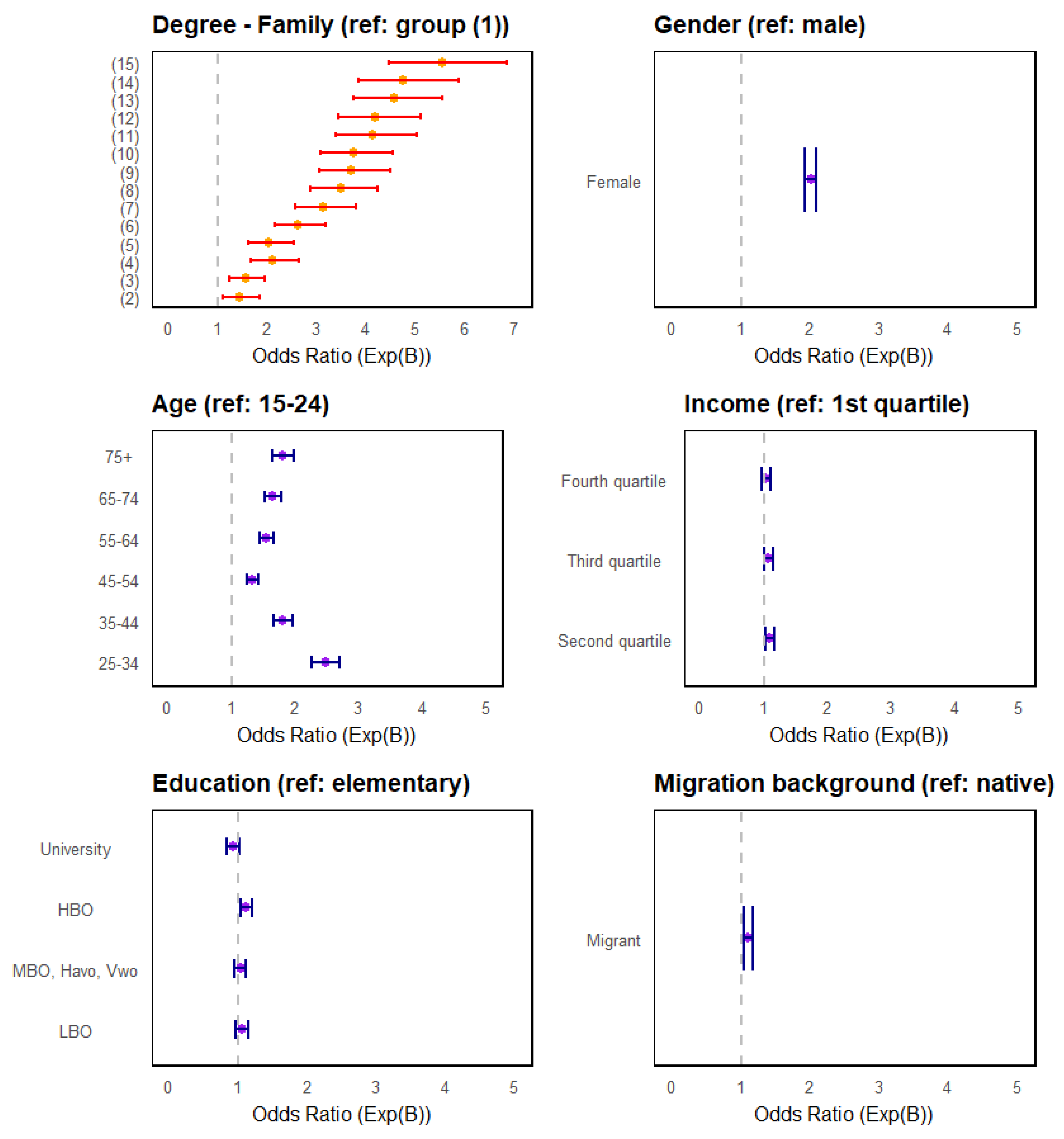

3.2.2. Model 2: Adding General Attributes

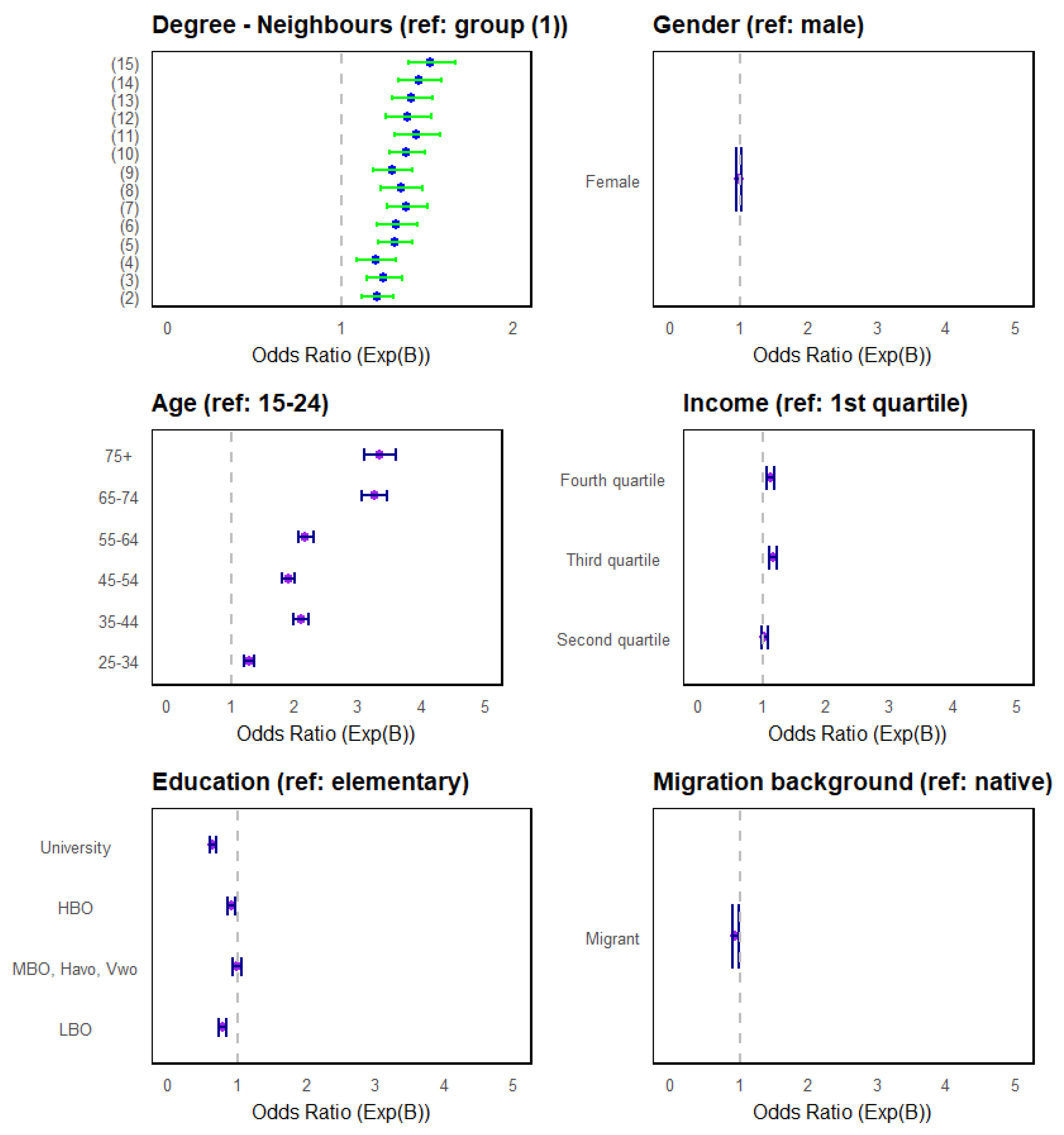

In Model 2, we extended the analysis by incorporating controls alongside degree centrality within each network layer to correct for the demographic and socio-economic composition of the 15 groups. In

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, we provide the odds ratios for degree centrality on maintaining contacts. A slightly larger percentage of the variance in Maintaining Contacts in both domains (Family and Neighbours) is explained by the combined factors, indicating improved explanatory power of Model 2 when compared to Model 1.

We further notice that after controlling for gender, age, education, income and migration background, the degree of family centrality clearly relates to the frequency of family contacts. The more family connections, the higher the chance that there is at least once per week a family contact. Interestingly, a clearer pattern for the contacts with neighbours emerges, suggesting the importance of taking into account the composition of the 15 neighbour centrality groups. The odds ratios increase gradually from 1.21 to 1.52 indicating that the chance for at least a weekly contact increased by half for the group with the highest centrality compared to the group with the lowest centrality.

Additionally, the controls also contribute significantly to the family contacts. Women have more contacts than men, people of intermediary-level education show more contacts than the lowest or highest educated, and the youngest age group has less contacts than all other age groups. Furthermore, the highest income groups have slightly more contacts with their family members than the lowest income group, and the migrants have more contacts than the native population. This model underscores the combined importance of family network size and demographic factors in predicting the maintenance of family relationships.

In addition to the presented models, we have performed a few robustness checks by adding more demographic and regional variables into the model, such as household composition, marital status, and urbanity. The inclusion of any of these variables had hardly any effect on the relationship between family centrality and family contacts. Likewise, we added the controls in the model for the weekly contacts with neighbours. While gender is not related to the contacts with neighbours, we notice that such contacts increase for higher age groups. In particular, the 65+ population show a high contact level. Furthermore, such contacts decrease for the higher educated, the middle-income groups have more contacts than the lowest income group, and the natives have slightly more contacts than the migrant population.

Although the regression models indicate statistically significant associations between network centrality and the likelihood of maintaining social contact, the substantive size of these effects is relatively modest when interpreted through predicted probabilities. Drawing on Model 2 estimates, individuals in the highest category of family degree centrality (Group 15) have an estimated probability of weekly family contact of 78 percent, while those in the lowest group (Group 1) show a probability of 52 percent. This 26-percentage point gap represents a clear and meaningful difference in behaviour, but it also suggests that even a large family network does not guarantee frequent contact. The pattern is far less pronounced for neighbour centrality. Here, predicted probabilities range only from 42 percent in the lowest group to 49 percent in the highest—a narrow spread of just 7 percentage points across the entire centrality spectrum.

These predicted probabilities help contextualize the underlying odds ratios. For family networks, the top group exhibits odds of weekly contact more than five times greater than those with minimal connections. For neighbours, odds ratios climb to around 1.5 at most and do so without a clear linear progression, indicating that structural proximity, as captured in administrative measures, plays only a limited role in shaping neighbourly interaction.

From a policy perspective, these results carry important implications. Degree centrality, in its current form, captures a structural form of embeddedness but fails to account for the qualitative dimensions of social ties that shape actual contact patterns. Its limited explanatory power, especially in the neighbour domain, cautions against treating it as a meaningful standalone proxy for social capital and its underlying trust and participation indicators. If administrative data are to serve as tools for social monitoring or policy design, more sophisticated indicators will be needed—ones that reflect not only the quantity of ties but their weight, intensity, and functional meaning in daily life. These findings emphasize the gap between network structure as abstracted from registers and the behavioural realities captured in surveys, underscoring the need for care in bridging the two in empirical and policy contexts.

4. Conclusions

This study drew on two highly distinct data sources maintained by Statistics Netherlands: the Person Network file, based on administrative microdata and offering full-population coverage of relational ties, and the Social Cohesion and Well-being (SSW) survey, a nationally representative sample capturing self-reported indicators of, among other factors, participation, trust, and social contact. The Person Network file is a novel and internationally unique dataset, regarded as a groundbreaking infrastructure for population-scale network research. It has been widely praised, has led to a growing collaborative research agenda across Dutch universities and CBS researchers, and is selectively accessible only to certified researchers due to its sensitive microdata.

Given this conceptual promise, we set out to investigate whether the structural embeddedness reflected in the administrative Person Network data corresponds meaningfully with behavioural indicators of social capital captured in the SSW survey. Grounded in theories of social capital and cohesion—and constrained by what each data source could offer—we began with the most direct strategy: simple cross-tabulations and correlations between survey indicators and a range of centrality metrics derived from the Person Network file.

Among the various possibilities, only degree centrality measures—particularly those pertaining to family and neighbour layers—emerged as technically feasible for further analysis. These were the only network metrics for which connections involving SSW respondents were sufficiently available and interpretable. On the SSW side, we leveraged a rich array of validated indicators traditionally associated with social capital. This initial approach provided a baseline for examining whether the administrative data could serve as a proxy for self-reported social engagement and trust.

We tested degree centrality including variations, including logarithmic transformations and weighing by distance and their associations with 17 indicators of social capital that fit the headings of trust and participation in the selected theoretical model. However, even these more refined measures revealed very weak correlations. We proceeded by identifying the only layers where correlation patterns showed at least some promise—namely, family and neighbour degree centralities. From a theoretical standpoint, one might expect these forms of embeddedness to be closely associated with social capital. However, even here, the associations were faint.

We then narrowed the scope further to the most fundamental social indicators available in SSW: self-reported frequency of maintaining contact with family and with neighbours. These offer the most direct behavioural proxies for actual engagement within those respective relational domains.

In a series of logistic regression analyses using self-reported frequency of contact as the dependent variable, we find that individuals with higher relative network centralities are more likely to maintain frequent contact with both family members and neighbours. This association is notably stronger and more consistent in the context of family ties than for neighbour relationships. A possible explanation of weaker neighbour centrality–contact associations is that in the SSW survey, the question refers to contacts with direct neighbours, while the measure of neighbour centrality currently includes all people within a 200 m radius of the respondent.

Additionally, we demonstrated that inclusion of demographic and socio-economic controls adds to the understanding of network centralities linked to social contacts, although the increase in explained variance remains low. This suggests that centrality and the included controls are not sufficient predictors of actual social contacts. This could be due to the complexity of social interactions between family members and between neighbours, where factors such as the quality of relationships, social norms, and individual preferences play a significant role.

These weak correlations between survey and administrative data suggest that some of the key steps in future research would be to look for the reasons why there might be hardly any impact of the social networks on the actual social behaviour, assessed via the SSW surveys, even when it comes to relationships with their own family, let alone the neighbours. Given the design and scope of the Social Cohesion and Well-being (SSW) survey, this study is not meaningfully affected by classical forms of selection bias. The SSW employs a probability-based sampling frame to produce a nationally representative cross-section of the Dutch population, with 83,667 respondents pooled across eleven annual waves. This extensive sample ensures that all major sociodemographic groups are robustly covered, including by age, gender, income, education, and migration background. As such, concerns about self-selection or exclusion are unfounded: the representativeness and statistical power of the SSW sample render it one of the most comprehensive social cohesion and well-being survey infrastructures in Europe.

A key reason for the weak associations we gather lies in the structural design of the Person Network data, and specifically in the limitations of our analytical scope. For this study, we only observe network connections involving individuals in the SSW survey sample—meaning we do not have access to the full national network, but only to the slices involving these respondents. Even if full population data were available, however, the Person Network does not constitute a real social network in the sociological sense. For example, the family layer is structured as a hierarchical tree based on legal kinship ties, which inherently excludes lateral or extended linkages and blocks the use of network measures that assume broader connectivity. The neighbour layer is particularly problematic: each respondent is linked to up to 200 individuals based on co-residence within a 200 m radius, forming a hub-and-spoke structure with no visibility into ties among the surrounding nodes or beyond. These are not interactional networks but administrative abstractions of spatial or institutional proximity. As a result, network layers collapse into fragmented ego-structures, and only simple metrics like degree centrality—perhaps weighted, and only meaningfully in the family layer—can be used with any interpretive caution.

Beyond methodological and analytical implications, this study also touches deeper normative issues that arise when linking administrative microdata with survey responses to monitor social networks and cohesion. While the data used are fully compliant with GDPR regulations and access is restricted to certified researchers, population-scale analyses of relational patterns inevitably raise questions about public trust, transparency, and data sovereignty. The very strength of the data—its unprecedented scope and granularity—also amplifies its sensitivity. It is crucial that researchers, institutions, and policymakers engage with these ethical dimensions openly, ensuring that such infrastructures are developed and interpreted with accountability and legitimacy. These concerns grow in importance as administrative data increasingly become tools for social diagnostics and policy design.

Future research should aim to address several key areas to build upon our findings. First, enhancing the quality and comprehensiveness of register data, particularly in the abstraction of networks into centrality measures, is crucial. This includes redefining the parameters for what constitutes a neighbourhood, workplace, or school network, ensuring more realistic distributions. Additionally, incorporating more layers and dimensions of relationships will provide a more accurate and detailed picture of social networks. This approach will better capture the diversity and dynamics of networks over time, integrating additional data sources to enrich the existing datasets.

Second, as network analysis of centrality is limited without accounting for the weights of relationships, future research should aim to integrate the strength and quality of ties into centrality measures. Our preliminary attempts to incorporate weighted centrality measures—such as distance weighting and logarithmic transformations—yielded no substantial improvement in associations with social cohesion indicators. Nevertheless, this remains a promising direction that warrants further exploration. A parent should be given a higher weight than a cousin. Weighted network analysis can provide a more nuanced understanding of social networks by distinguishing between strong and weak ties, thus offering a clearer picture of how different types of relationships impact social capital cohesion. Yet, this is not trivial and requires a well-designed network abstraction methodology, evolving from a binary towards a weighted (even directed) approach, particularly when it comes to network layers beyond the basic family layer, which remain problematic at present.

Third, the SSW data allow for focussing on specific regions and municipalities. By integrating more information of neighbourhoods such as social and cultural facilities enhancing social contacts could highlight unique cultural or structural factors influencing social cohesion. This would provide a broader context and help identify universal versus context-specific dynamics.

Fourth, while the findings of this study are based on a sample from the Netherlands, the external validity of these results, especially in terms of geographic applicability, is limited. Although the dataset is comprehensive and includes a large number of respondents, caution must be exercised when generalizing the results to other geographical contexts, or, ideally, other geographical regions should be explored as well. The unique characteristics of Dutch society, including its social policies, urban infrastructure, and demographic composition, may not fully represent conditions in other countries or regions. However, the large sample size and richness of the data do provide a valuable foundation for understanding social network centrality and social capital within this context. Future studies could extend this approach to other countries or regions to examine whether similar patterns of social network centrality and social capital hold true across diverse geographical settings. In addition, further research could move beyond descriptive demonstration to test more substantive hypotheses. For example, future studies might leverage the social capital index derived here to predict key outcomes—such as health, well-being, economic participation, or segregation patterns—across different regions or population subgroups. These questions could build toward a richer understanding of the distributive impact and the role of individual-level capital in shaping broader community dynamics. Comparative studies might also investigate whether the influence of socially embedded individuals varies by their alignment with or difference from local majorities, for example, by exploring how ethnic minorities with high social capital affect longer-term social outcomes in homogenous areas.

Lastly, future research might be dedicated to exploring the relationship between social capital and the components of well-being, such as happiness and life satisfaction, and broader well-being including physical and mental health, leisure time, work, school, housing, relationships, financial situation, and neighbourhood safety (included in the SSW). Insights from this research could guide policymakers, mental health professionals, urban planners, and educators in fostering environments that enhance social capital, ultimately improving well-being across populations.

By addressing these and other domains, we can significantly enhance our understanding of social networks and social capital, ultimately contributing to more effective strategies for fostering well-being and community resilience in the Netherlands and beyond.