Decomposing the Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion: An Oaxaca–Blinder Analysis for Peru, 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptual Aspect of Financial Inclusion

2.2. Gender Perspective and Economic Inequality

2.3. Complementary Theories and Approaches on Financial Inclusion

2.3.1. Human Capital Theory

2.3.2. Social Exclusion Approach

2.3.3. Structuralist Approach

2.4. Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition Models

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach and Design

3.2. Population and Sample

3.3. Variables and Operationalization

3.4. Econometric Model Specification

- if individual i has access and uses financial services; 0 otherwise.

- is the vector of independent variables (education, income, occupation, geographic location, household size, marital status, gender, age).

- is the vector of estimated parameters.

- F(·) is the cumulative logistic distribution function.

- Explained component (E): Due to differences in observable characteristics (education, income, occupation, location, etc.).

- Unexplained component (U): Due to differences in returns to those characteristics or unobserved factors (e.g., discrimination, social norms).

- is the average difference in financial inclusion between men (M) and women (F).

- is the average of the characteristics for each group.

- is the vector of reference coefficients (can be or combined weight).

3.5. Ethical Aspects

3.6. Limitations of the Research

4. Results

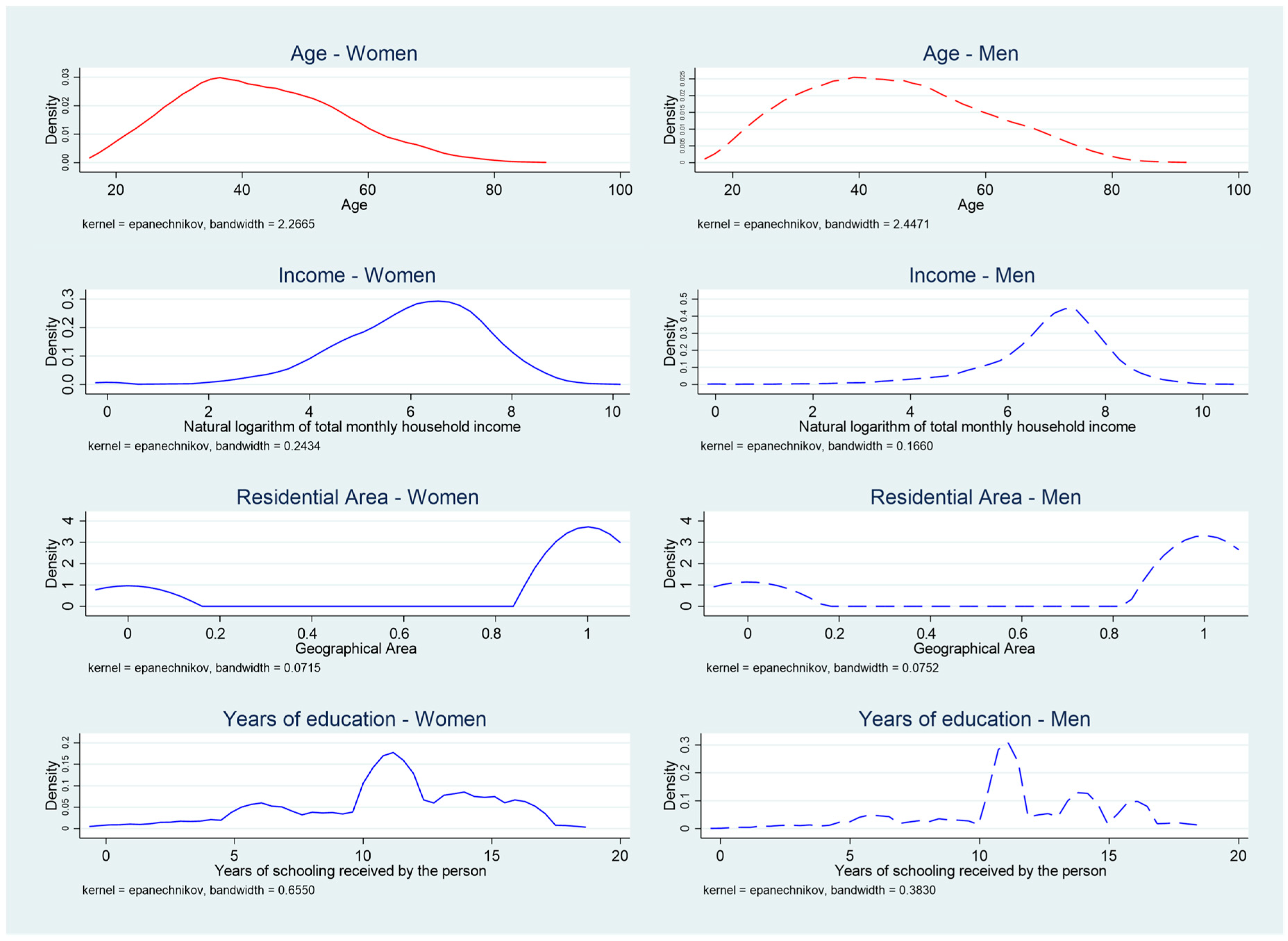

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Variables Involved in the Gender Financial Inclusion Gap

4.2. Application of the Oaxaca–Blinder Model to Explain the Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion

4.2.1. Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion: Magnitude and General Decomposition

- Explained component (endowments), which accounts for 3.21 percentage points (p < 0.01). This indicates that if women had the same observable characteristics as men (e.g., education, income, and age), their financial inclusion would actually be higher.

- The unexplained component (coefficients), valued at −7.24 percentage points (p < 0.01), shows that the largest portion of the gap is due to differences in how the financial system values these characteristics between men and women.

- Interaction component (combined effect of characteristics and returns), valued at 1.88 percentage points (p < 0.05), indicates a partial moderation of the gap.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Gender Gap: Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition | Gender Gap: Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition | Gender Gap: Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition | Gender Gap: Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition |

| Natural logarithm of total monthly household income | 0.0192 *** | 0.108 ** | 0.0136 ** | |

| (0.00473) | (0.0515) | (0.00653) | ||

| Age | −0.00413 *** | 0.106 ** | 0.00301 ** | |

| (0.00141) | (0.0421) | (0.00143) | ||

| Years of education received | 0.0132 *** | 0.118 *** | 0.00702 *** | |

| (0.00228) | (0.0304) | (0.00207) | ||

| Marital status | −0.00655 *** | −0.0294 | 0.00412 | |

| (0.00215) | (0.0196) | (0.00278) | ||

| Household size | 2.31 × 10−5 | −0.0601 ** | −0.000708 | |

| (0.000237) | (0.0265) | (0.000717) | ||

| Main occupational category | 0.0103 *** | 0.121 | −0.00372 | |

| (0.00228) | (0.0772) | (0.00240) | ||

| Area of residence | −0.00127 | 0.0425 ** | −0.00391 ** | |

| (0.00149) | (0.0212) | (0.00197) | ||

| Geographical region of household | 0.00103 | −0.0106 | −0.000143 | |

| (0.00106) | (0.0267) | (0.000388) | ||

| Participation in a social program | 0.000253 | −0.0248 | −0.000528 | |

| (0.000341) | (0.0164) | (0.000592) | ||

| Group 1 | 0.509 *** | |||

| (0.00791) | ||||

| Group 2 | 0.531 *** | |||

| (0.00876) | ||||

| Difference | −0.0216 * | |||

| (0.0118) | ||||

| Endowments | 0.0321 *** | |||

| (0.00662) | ||||

| Coefficients | −0.0724 *** | |||

| (0.0130) | ||||

| Interaction | 0.0188 ** | |||

| (0.00795) | ||||

| Constant | −0.443 *** | |||

| (0.131) | ||||

| Observations | 14,240 | 14,240 | 14,240 | 14,240 |

4.2.2. Comparison Between the Unweighted Model and the Weighted Model (Simple Adjustment)

- The natural logarithm of household income has a significant and positive effect on both the endowment component (0.0192, p < 0.01), especially on the return’s component (0.108, p < 0.05), indicating that monthly household income contributes more to improving financial inclusion for men than for women.

- In the case of age, the value is negative in the endowment component (−0.00413, p < 0.01) but positive and significant in the return’s component (0.106, p < 0.05), demonstrating that age is valued differently and more favorably for men.

- Years of education have a positive effect on both components, though with a stronger impact on returns (0.118, p < 0.01), highlighting education as a crucial factor, but one that is more highly rewarded for men.

- Marital status has a negative and significant effect only on the endowment component (−0.00655, p < 0.01), indicating that women in certain family conditions face additional barriers to financial access.

- Household size, although showing no effect in the endowment component, has a significantly negative effect in the return’s component (−0.0601, p < 0.05), suggesting that this variable disproportionately reduces financial inclusion for women.

- Regarding area of residence (urban vs. rural), the endowment component shows no significant effect, while the returns component is significantly positive (0.0425, p < 0.05), indicating that living in urban areas offers greater financial benefits for men than for women.

- Occupational category (working in the formal sector) shows favorable endowments for men (0.0103, p < 0.01), although the returns are not statistically significant.

- Other variables, such as the household’s geographical region (Coast, Highlands, or Jungle) and participation in social programs, do not show statistically significant contributions, although they may be relevant from a qualitative or public policy perspective.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdu, Esmael, and Mohammd Adem. 2021. Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Afar Region: Evidence from Selected Woredas. Cogent Economics and Finance 9: 1920149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, Gabriela, and Mayra Buvinic. 2019. Enabling Women’s Financial Inclusion Through Data: The Case of Mexico. Mexico City: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyangwe, Tony, Annabel Vanroose, and Ashenafi Fanta. 2022. Determinants of Financial Inclusion: Does Culture Matter? Cogent Economics and Finance 10: 2073656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armest, Ronald Hidalgo, Katherine Ivonne Suncion Alban, and Mario Villegas Yarleque. 2021. Impact of Social, Geographic and Economic Variables on Formal Financial Inclusion for Households in Peru and Piura 2019. Universidad Ciencia y Tecnología 25: 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, Douglas W., Ross P. Buckley, Dirk A. Zetzsche, and Robin Veidt. 2020. Sustainability, FinTech and Financial Inclusion. European Business Organization Law Review 21: 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, Paulina Perla. 2007. El Retorno de La Teoría Del Capital Humano. The Return of Human Capital Theory 8: 9–26. (In English). [Google Scholar]

- Arun, Thankom, and Rajalaxmi Kamath. 2015. Financial Inclusion: Policies and Practices. IIMB Management Review 27: 267–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, Goksu, Corinne Deléchat, Monique Newiak, and Fan Yang. 2017. Inequality in Financial Inclusion and Income Inequality. IMF Working Papers 2017: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirne, John, David G. Fernandez, Sabyasachi Tripathi, and Meenakshi Rajeev. 2023. Gender-Inclusive Development through Fintech: Studying Gender-Based Digital Financial Inclusion in a Cross-Country Setting. Sustainability 15: 10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, Alan S. 1973. Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural Estimates. The Journal of Human Resources 8: 436–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitano, Guillermo, and Deyvi Franco Abanto. 2020. Desafíos de Las Políticas de Inclusión Financiera En El Perú. Revista Finanzas y Política Económica 12: 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalup, Miguel, Manuel Urquidi, and Liliana Serrate. 2023. Changes in Peru’s Gender Earning Gap: An Analysis from 1997 to 2021. Lima: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confraria, Hugo, Tommaso Ciarli, and Ed Noyons. 2024. Countries’ Research Priorities in Relation to the Sustainable Development Goals. Research Policy 53: 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delechat, Corinne, Monique Newiak, Rui Xu, Fan Yang, and Goksu Aslan. 2018. What Is Driving Women’s Financial Inclusion Across Countries? IMF Working Papers 2018: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, Saniya Ansar, and Jake Hess. 2018. The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution. Washington: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, and Saniya Ansar. 2022. The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. Washington: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhahri, Sabrine, Anis Omri, and Nawazish Mirza. 2024. Information Technology and Financial Development for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Research in International Business and Finance 67: 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, Adolfo, and Herrera García. 2019. Inclusión Financiera Femenina En México: Una Herramienta Para Su Empoderamiento. FEMERIS: Revista Multidisciplinar de Estudios de Género 4: 158–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, Daniela, and Sally Brooks. 2017. The Digital Revolution in Financial Inclusion: International Development in the Fintech Era. New Political Economy 22: 423–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Allan Herminio Vargas. 2021. Inclusión Financiera En Perú y Latinoamérica En Tiempos Del COVID-19. Quipukamayoc 29: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Naím Manríquez, Lidia Rangel Blanco, and Ramiro Esqueda Walle. 2024. Determinantes Del Crédito e Inclusión Financiera En Mujeres Jefas de Hogar En México. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 30: 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Sampieri, Roberto. 2018. Metodología de La Investigación: Las Rutas Cuantitativa, Cualitativa y Mixta. Ciudad de México: McGraw Hill México. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Cano, Carolina, Arley Pino-Villegas, Carlos Felipe Munera-Alzate, and Maria Alejandra Gonzalez-Perez. 2024. Financial Inclusion of Rural Women in the Global South. In Financial Inclusion. Sustainable Development Goals Series; Cham: Springer, pp. 123–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jann, Ben. 2008. The Blinder-Oaxaca Decomposition for Linear Regression Models. Stata Journal 8: 453–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma’ruf, Ahmad, and Febriyana Aryani. 2019. Financial Inclusion and Achievements of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in ASEAN. GATR Journal of Business and Economics Review 4: 147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Waldo. 2014. Cómo Investigan los Economistas: Guía para Elaborar y Desarrollar un Proyecto de Investigación. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la PUCP. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, Seifelyazal, Salah Eldin Ashraf, and ElSherif Marwa. 2023. The Impact of Financial Inclusion on Economic Development. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 13: 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ñopo, Hugo R. 2012. New Century, Old Disparities: Gender and Ethnic Earnings Gaps in Latin America and The Caribbean. Washington: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Olarte, Sofía. 2017. Brecha Digital, Pobreza y Exclusión Social. Temas Laborales 138: 285–313. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6552396 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Orazi, Sofía, Lisana Belén Martínez, and Hernán Pedro Vigier. 2021. Inclusión Financiera En Argentina: Un Estudio Por Hogares. Revista de La Facultad de Ciencias Económicas 26: 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Vásquez, Manuel Antonio, and Francia Helena Prieto-Baldovino. 2019. Determinación Del Impacto Socioeconómico de Las Políticas de Inclusión Financiera En El Municipio de Montería. Clío América 13: 350–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, Pablo, Jaime Andrés Correa-García, Carmen Stella Verón, Pablo Raffaelli, Jaime Andrés Correa-García, and Carmen Stella Verón. 2025. Inclusión Financiera y Fintech: Catalizadores de Los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible En América Latina. RETOS. Revista de Ciencias de La Administración y Economía 15: 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Asis, Hernan, Jorge Castillo-Picon, Jenny Villacorta Miranda, Jośe Rodŕiguez Herrera, and Walter Medrano Acuña. 2024. Socioeconomic Factors and Financial Inclusion in the Department of Ancash, Peru, 2015 and 2021. In Technological Innovations for Business, Education and Sustainability. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Zaga, Fernando, Fernando Antonio, and Ramos Zaga. 2024. Factores Determinantes de La Exclusión Financiera Femenina: Revisión Sistemática. Newman Business Review 10: 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Raúl Moreira. 2021. Inclusión Financiera En Panamá. Investigación y Pensamiento Crítico 9: 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, María José, and Alejandra Villegas. 2023. Financial Exclusion and the Importance of Financial Literacy. In Research Handbook on Measuring Poverty and Deprivation. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 283–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, Ratna, Martin Cihak, Papa M. N’Diaye, Adolfo Barajas, Srobona Mitra, Annette J. Kyobe, and Reza Yousefi. 2025. Financial Inclusion: Can It Meet Multiple Macroeconomic Goals? September. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2016/12/31/Financial-Inclusion-Can-it-Meet-Multiple-Macroeconomic-Goals-43163 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Singer, Dorothe, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Leora Klapper. 2013. Financial Inclusion and Legal Discrimination Against Women: Evidence from Developing Countries. Washington: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Pedro Luis Grados. 2021. Implications of Financial Inclusion and Informal Employment on Monetary Poverty of Peru Departments. Revista Finanzas y Politica Economica 13: 545–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumlinski Mariusz, A., Bas B. Bakker, Beatriz Garcia-Nunes, Weicheng Lian, Yang Liu, Camila Perez Marulanda, Adam Siddiq, Yuanchen Yang, and Dmitry Vasilyev. 2023. The Rise and Impact of Fintech in Latin America. Fintech Notes 2023: 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, Vighneswara. 2014. Financial Inclusion, Gender Dimension, and Economic Impact on Poor Households. World Development 56: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temoso, Omphile, John N. Ng’ombe, and Kwabena N. Addai. 2024. Gender and Geographical Disparities in Financial Inclusion in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa: A Kitagawa-Oaxaca-Blinder Decomposition. In Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Rural Development. Sustainable Development Goals Series; Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 229–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, Shirley Escalante. 2025. Brechas de Género En El Acceso a Los Servicios Financieros En El Perú. Revista FAECO Sapiens 8: 132–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Salazar, Ivonne Yanete, Cristhian Alonso Aquino-Yaile, Madalyne Motta-Flores, Ivonne Yanete Vargas-Salazar, Cristhian Alonso Aquino-Yaile, and Madalyne Motta-Flores. 2025. Inclusión Financiera En El Perú: Análisis de Factores Socioeconómicos, Geográficos y Tecnológicos. Revista de Economía Institucional 27: 261–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Variable | Indicator | Scale | Source/Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | Financial inclusion | Access and use of financial services (bank account ownership, usage) | Binary (Yes/No) | ENAHO, Module 500 |

| Independent | Years of education | Total years of schooling | Discrete quantitative | ENAHO, Module 300 |

| Household income | Natural log of total monthly household income | Continuous (S/.) | ENAHO, Module 500 | |

| Occupation | Main occupational category (formal, informal, unemployed, self-employed) | Nominal categorical | ENAHO, Module 500 | |

| Geographic location | Area of residence (urban/rural) | Nominal categorical | ENAHO, Module 100 | |

| Household size | Total number of household members | Discrete quantitative | ENAHO, Module 200 | |

| Marital status | Marital status (single, married, cohabiting, separated, widowed) | Nominal categorical | ENAHO, Module 200 | |

| Gender | Sex of the respondent (male/female) | Nominal categorical | ENAHO, Module 200 | |

| Age | Completed years of age | Continuous | ENAHO, Module 200 |

| Variables | Category | Gender | Total | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||||

| Financial Inclusion | No | 3957 | 2961 | 6918 | Pearson chi2(1) = 22.7286 |

| % | 57.20 | 42.80 | 100.00 | ||

| Yes | 3897 | 3425 | 7322 | ||

| % | 53.22 | 46.78 | 100 | ||

| Total | 7854 | 6386 | 14,240 | Pr = 0.000 | |

| % | 55.15 | 44.85 | 100.00 | ||

| Variable | Men’s Mean | Women’s Mean | Difference | T-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of education | 10.343 | 9.880 | 0.463 | 7.179 | 0.0000 |

| Log household monthly income | 6.561 | 5.911 | 0.650 | 28.088 | 0.0000 |

| Age | 45.275 | 44.302 | 0.973 | 4.339 | 0.0000 |

| Household size | 3.904 | 3.863 | 0.041 | 1.338 | 0.1808 |

| Variable | Category | Group | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Women | Rural Women | Urban Men | Rural Men | |||

| Financial Inclusion | No | 2168 | 793 | 2233 | 1724 | 6918 |

| % | 31.34 | 11.46 | 32.28 | 24.92 | 100.00 | |

| Yes | 2720 | 705 | 2898 | 999 | 7322 | |

| % | 37.15 | 9.63 | 39.58 | 13.64 | 100 | |

| Total | 4888 | 1498 | 5131 | 2723 | 14,240 | |

| % | 34.33 | 10.52 | 36.03 | 19.12 | 100.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quispe-Mamani, J.C.; Aguilar-Pinto, S.L.; Incacutipa-Limachi, D.J.; Quispe-Layme, M.; Flores-Turpo, G.A.; Cáceres-Quenta, R.; Alegre-Larico, M.I.; Mamani-Flores, A.; Velásquez-Velásquez, W.L.; Rosado-Chávez, C.A.; et al. Decomposing the Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion: An Oaxaca–Blinder Analysis for Peru, 2024. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090567

Quispe-Mamani JC, Aguilar-Pinto SL, Incacutipa-Limachi DJ, Quispe-Layme M, Flores-Turpo GA, Cáceres-Quenta R, Alegre-Larico MI, Mamani-Flores A, Velásquez-Velásquez WL, Rosado-Chávez CA, et al. Decomposing the Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion: An Oaxaca–Blinder Analysis for Peru, 2024. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090567

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuispe-Mamani, Julio Cesar, Santotomas Licimaco Aguilar-Pinto, Duverly Joao Incacutipa-Limachi, Marleny Quispe-Layme, Giovana Araseli Flores-Turpo, Rolando Cáceres-Quenta, Maria Isabel Alegre-Larico, Adderly Mamani-Flores, Wily Leopoldo Velásquez-Velásquez, Charles Arturo Rosado-Chávez, and et al. 2025. "Decomposing the Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion: An Oaxaca–Blinder Analysis for Peru, 2024" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090567

APA StyleQuispe-Mamani, J. C., Aguilar-Pinto, S. L., Incacutipa-Limachi, D. J., Quispe-Layme, M., Flores-Turpo, G. A., Cáceres-Quenta, R., Alegre-Larico, M. I., Mamani-Flores, A., Velásquez-Velásquez, W. L., Rosado-Chávez, C. A., & Guevara-Mamani, M. (2025). Decomposing the Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion: An Oaxaca–Blinder Analysis for Peru, 2024. Social Sciences, 14(9), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090567