The Value of Quality in Social Relationships: Effects of Different Dimensions of Social Capital on Self-Reported Depression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Social Capital Theory and Previous Research

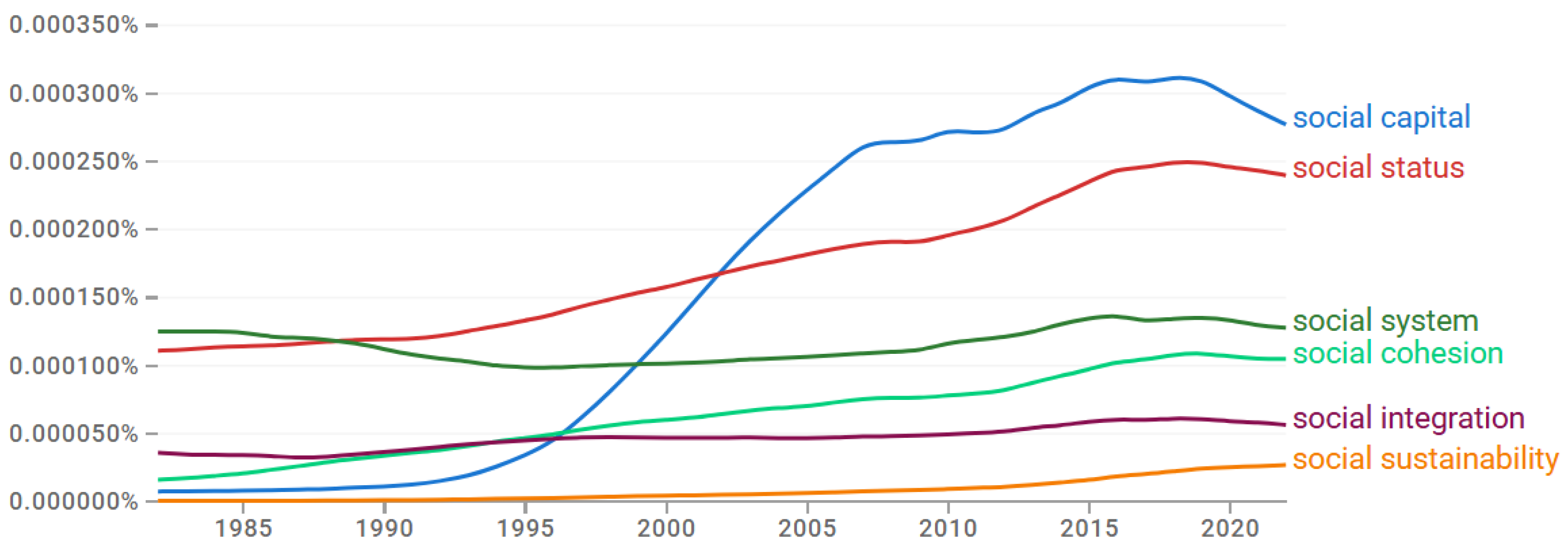

2.1. The Theory of Social Capital: A Complex and Multi-Dimensional Concept

2.2. Applying the Concept of Social Capital in Practice

2.3. Social Capital and Health

2.4. Social Capital and Depression in Eastern Europe

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Variables Studied

3.2. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | Men | Women | Total | p * | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | 0.004 | 2074 | |||

| Married | 62 | 55 | 58 | ||

| Non-married | 38 | 45 | 42 | ||

| Contact with relatives | <0.0005 | 2062 | |||

| Frequent | 73 | 82 | 78 | ||

| Infrequent | 27 | 18 | 22 | ||

| Contact with friends | 0.025 | 2030 | |||

| Frequent | 75 | 70 | 72 | ||

| Infrequent | 25 | 30 | 28 | ||

| Contact with neighbours | 0.535 | 2093 | |||

| Frequent | 74 | 76 | 75 | ||

| Infrequent | 26 | 24 | 25 | ||

| Voluntary associations | 0.419 | 1965 | |||

| Member | 57 | 55 | 56 | ||

| Non-member | 43 | 45 | 44 |

| Variables | Men | Women | Total | p * | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family (marital status) | 7.9 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 0.002 | 1897 |

| Relatives | 7.4 | 8.0 | 7.7 | <0.0005 | 2006 |

| Friends | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 0.668 | 1898 |

| Neighbours | 6.2 | 6.6 | 6.4 | <0.0005 | 1666 |

| Voluntary associations | 4.7 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 0.108 | 597 |

4.2. Associations Between Social Capital and Self-Reported Depression

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | Wald | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | 4.32 | 1664 | ||

| Married | 1.00 | |||

| Non-married | 1.26 | 1.01–1.57 * | ||

| Contact with relatives | 9.58 | 1664 | ||

| Frequent | 1.00 | |||

| Infrequent | 1.50 | 1.16–1.94 ** | ||

| Contact with friends | 1.26 | 1641 | ||

| Frequent | 1.00 | |||

| Infrequent | 1.15 | 0.90–1.47 | ||

| Contact with neighbours | 33.30 | 1687 | ||

| Frequent | 1.00 | |||

| Infrequent | 2.01 | 1.59–2.55 *** | ||

| Voluntary associations | 2.16 | 1593 | ||

| Member | 1.00 | |||

| Non-member | 0.84 | 0.67–1.06 |

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | Wald | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family (marital status) | 1.16 | 1.10–1.23 *** | 29.90 | 1526 |

| Relatives | 1.16 | 1.11–1.23 *** | 30.65 | 1541 |

| Friends | 1.06 | 1.00–1.14 | 3.73 | 1620 |

| Neighbours | 1.18 | 1.12–1.24 *** | 38.38 | 1607 |

| Voluntary associations | 0.98 | 0.91–1.05 | 0.46 | 480 |

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | Wald | AME | p (AME) | Nagelkerke R2 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact with relatives | |||||||

| Infrequent (structural) | 1.34 | 1.01–1.77 * | 4.24 | 0.066 | 0.018 | ||

| Burdening (qualitative) | 1.15 | 1.09–1.22 *** | 24.02 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.036 | 1518 |

| Contact with friends | |||||||

| Infrequent (structural) | 1.08 | 0.83–1.40 | 0.31 | 0.028 | 0.303 | ||

| Burdening (qualitative) | 1.04 | 0.98–1.12 | 1.58 | 0.006 | 0.411 | 2.32 × 10−3 | 1578 |

| Contact with neighbours | |||||||

| Infrequent (structural) | 1.53 | 1.17–2.00 ** | 9.40 | 0.088 | 0.001 | ||

| Burdening (qualitative) | 1.13 | 1.07–1.20 *** | 19.61 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 1601 |

4.2.1. Controlling for Age, Sex, Education, and Economic Satisfaction

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | Wald | AME | p (AME) | Nagelkerke R2 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact with relatives | |||||||

| Infrequent (structural) | 1.43 | 1.05–1.93 * | 5.25 | 0.078 | 0.007 | ||

| Burdening (qualitative) | 1.15 | 1.08–1.22 *** | 18.43 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.127 | 1349 |

| Contact with friends | |||||||

| Infrequent (structural) | 1.18 | 0.88–1.59 | 1.26 | 0.038 | 0.193 | ||

| Burdening (qualitative) | 1.10 | 1.02–1.18 * | 5.98 | 0.016 | 0.028 | 0.103 | 1404 |

| Contact with neighbours | |||||||

| Infrequent (structural) | 1.26 | 0.94–1.68 | 2.37 | 0.054 | 0.055 | ||

| Burdening (qualitative) | 1.13 | 1.06–1.20 *** | 14.70 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.111 | 1422 |

4.2.2. The Effect of Missing Values

5. Discussion

5.1. Different Dimensions of Social Capital and Their Association with Reported Depression

5.2. Different Forms of Social Capital and Their Association with Self-Reported Depression

5.3. Methodological Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbot, Pamela, and Claire Wallace. 2010. Explaining economic and social transformations in post-Soviet Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. European Societies 12: 6653–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlborg, Mikael G., Maria Nyholm, Jens M. Nygren, and Petra Svedberg. 2022. Current conceptualization and operationalization of adolescents’ social capital: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 15596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baycan, Tüzin, and Özge Öner. 2023. The dark side of social capital: A contextual perspective. Annals of Regional Science 70: 779–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behtoui, Alireza. 2017. Social capital and the educational expectations of young people. European Educational Research Journal 16: 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertossi Carla, Urzua, Milagros Ruiz, Andrzej Pajak, Magdalena Kozela, Ruzena Kubinova, Sofia Malyutina, Anne Peasey, Hynek Pikhart, Michael Marmot, and Martin Bobak. 2019. The prospective relationship between social cohesion and depressive symptoms among older adults from Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 72: 117–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of social capital. In Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Edited by John Richardson. New York: Greenwood, pp. 241–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1994. Sociology in Question. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bursztein Lipsicas, Cendrine, Ilkka Henrik Mäkinen, Danuta Wasserman, Alan Apter, Ad Kerkhof, Konrad Michel, Ellinor Salander Renberg, Kees van Heeringen, Airi Värnik, and Armin Schmidtke. 2013. Gender distribution of suicide attempts among immigrant groups in European countries—An international perspective. European Journal of Public Health 23: 279–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo Álvarez, Elena, and Jordi Riera Romaní. 2017. Measuring social capital: Further insights. Gaceta Sanitaria 31: 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo Álvarez, Elena, Ichiro Kawachi, and Jordi Riera Romani. 2017. Family social capital and health—A systematic review and redirection. Sociology of Health & Illness 39: 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Per. 2016. Trust and health in Eastern Europe: Conceptions of a new society. International Journal of Social Welfare 1: 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiese, Antonio. 2007. Measuring social capital and its effectiveness. The case of small entrepreneurs in Italy. European Sociological Review 23: 437–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James. 1988. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 94: 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James. 1991. Prologue: Constructed social organizations. In Social Theory for a Changing Society. Edited by Pierre Bourdieu and James Coleman. Boulder: Westview Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Karen S. 2015. Social capital and inequality: The significance of social connections. In Handbook of the Social Psychology of Inequality. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Edited by Jane D. McLeod, Edward Lawler and Michael Schwelbe. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 207–27. [Google Scholar]

- Delhey, Jan, and Kenneth Newton. 2005. Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: Global pattern of Nordic exceptionalism? European Sociological Review 21: 311–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Nadja. 2024. The role of trust in Belarusian societal mobilization (2020–2021). International Journal of Comparative Sociology 65: 537–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1997. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Glencoe: Free Press. First published 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Eshan, Annahita, and Mary De Silva. 2015. Social capital and common mental disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 69: 1021–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshan, Annahita, Hannah Sophie Klaas, Alexander Bastianen, and Dario Spini. 2019. Social capital and health: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Population Health 8: 100425. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlander, Sara. 2007. The importance of different forms of social capital for health. Acta Sociologica 50: 115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlander, Sara, and Ilkka Henrik Mäkinen. 2009. Social capital, gender and self-rated health. Evidence from the Moscow Health Survey 2004. Social Science & Medicine 69: 1323–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlander, Sara, Andrew Stickley, Olga Kislitsyna, Tanya Jukkala, Per Carlson, and Ilkka Henrik Mäkinen. 2016. Social capital—A mixed blessing for women? A cross-sectional study of different forms of social relations and self-rated depression in Moscow. BMC Psychology 4: 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, John. 2017. Social Capital, 3rd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fils, Jean, Elizabeth Penick, Elizabeth Nickel, Ekkehard Othmer, Cerilyn DeSouza, William Gabrielli, and Edward Hunte. 2010. Minor versus major depression: A comparative clinical study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 12: e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Forsman, Anna K., Fredrica Nyqvist, Ingrid Schierenbeck, Yngve Gustafson, and Kristian Wahlbeck. 2012. Structural and cognitive social capital and depression among older adults in two Nordic regions. Aging Mental Health 16: 771–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, H. Colin, Karen Block, Lisa Gibbs, David Forbes, Dean Lusher, Robyn Molyneaux, John Richardson, Philippa Pattison, Colin MacDougall, Richard A. Bryant, and et al. 2019. The effect of group involvement on post-disaster mental health: A longitudinal multilevel analysis. Social Science & Medicine 220: 161–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, Brenda, and Jennifer Roberts. 2020. Social capital: Exploring the theory and empirical divide. Empirical Economics 58: 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryakin, Yevgeniy, Marc Suhrcke, Bayard Roberts, and Martin McKee. 2015. Mental health inequalities in 9 former Soviet Union countries: Evidence from the previous decade. Social Science & Medicine 124: 142–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goryakin, Yevgeniy, Marc Suhrcke, Lorenzo Rocco, Bayard Roberts, and Martin McKee. 2014. Social capital and self-reported general and mental health in nine former Soviet Union countries. Health Economics & Policy Law 9: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Häuberer, Julia. 2014. Social Capital in Voluntary Associations: Localizing social resources. European Societies 16: 570–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglič, Hajdeja, Jesper Rözer, and Beate G. M. Volker. 2021. Economic crisis and social capital in European societies: The role of politics in understanding short-term changes in social capital. European Societies 23: 195–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, Johanna, and Markku Timonen. 2024. Social Capital and Depressive Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology 2024: 3278094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozela, Magdalena, Margin Bobak, Agnieszka Besala, Agnieszka Micek, Ruzena Kubinova, Sofia Malyutina, Diana Denisova, Marcus Richards, Hynek Pikhart, Anne Peasey, and et al. 2016. The association of depressive symptoms with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in Central and Eastern Europe. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 23: 1839–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, Anirudh, and Elizabeth Shrader. 1999. Social Capital Assessment Tool. Paper Prepared for the Conference on Social Capital and Poverty Reduction. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Nan. 2000. Inequality in social capital. Contemporary Sociology 29: 785–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan. 2001. Social Capital. A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lochner, Kimberly, Ichiro Kawachi, and Bruce Kennedy. 1999. Social capital: A guide to its measurement. Health & Place 5: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen, Ilkka Henrik. 2000. Eastern European transition and suicide mortality. Social Science & Medicine 51: 1405–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, Kwame, Rob Whitley, and Scott Weich. 2002. Social capital and mental health. British Journal of Psychiatry 181: 280–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell Usher, Carey, and Marc LaGory. 2002. Social capital and mental distress in an impoverished community. City Community 1: 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Spencer, and I. Ichiro Kawachi. 2017. Twenty years of social capital and health research: A glossary. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 71: 513–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Spencer, and Richard Carpiano. 2020. Measures of personal social capital over time: A path analysis assessing longitudinal associations among cognitive, structural, and network elements of social capital in women and men separately. Social Science & Medicine 257: 112172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxton, Pamela. 1999. Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology 105: 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, Floria, and Claire Wallace. 2007. Patterns of formal and informal social capital in Europe. European Sociological Review 23: 423–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinillos-Franco, Sara, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2019. The relationship between social capital and self-rated health: A gendered analysis of 17 European countries. Social Science & Medicine 219: 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, Alejandro. 1998. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Razvodovsky, Yury. 2015. Suicides in Russia and Belarus: A comparative analysis. Acta Psychopathologica 1: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sairambay, Yerkebulan. 2021. Political Culture and Participation in Russia and Kazakhstan: A New Civic Culture with Contestation? Slavonica 26: 116–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Ziggy Ivan, Paul E. Jose, Ai Koyanagi, Charlotte Meilstrup, Line Nielsen, Katrine R. Madsen, Carsten Hinrichsen, Robin I. M. Dunbar, and Vibeke Koushede. 2021. The moderating role of social network size in the temporal association between formal social participation and mental health: A longitudinal analysis using two consecutive waves of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 56: 417–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarracino, Francesco, and Malgorzata Mikucka. 2017. Social capital in Europe from 1990 to 2012: Trends, path-dependency and convergence. Social Indicators Research 131: 407–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, Peter, Ashley Boat, and Kent Pekel. 2020. Defining and Measuring Social Capital for Young People: A Practical Review of the Literature on Resource-Full Relationships. Report for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Minneapolis: Search Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Georg. 1981. On Individuality and Social Forms. Chicago: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Joonmo. 2020. Social Capital. Key Concepts. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrova, Olga, and Dongning Ren. 2020. Is more always better? Examining the nonlinear association of social contact frequency with physical health and longevity. Social Psychological & Personality Science 12: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Stolle, Dietlind, and Thomas Rochon. 1998. Are all associations alike? Member diversity, associational type and the creation of social capital. American Behavioral Scientist 42: 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, Ester, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2015. The measurement of social capital. Gaceta Sanitaria 29: 62–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalonga-Olives, Ester, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2017. The dark side of social capital: A systematic review of the negative health effects of social capital. Social Science & Medicine 194: 105–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiler, Michael, and Oliver Hinz. 2019. Without each other, we have nothing: A state-of-the-art analysis on how to operationalize social capital. Review of Managerial Science 13: 1003–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, Christian, Ronald Inglehart, and Franziska Deutsch. 2006. Social capital, voluntary associations and collective action: Which aspects of social capital have the greatest ‘civic’ payoff? Journal of Civil Society 1: 121–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Population Review. 2021. Depression Rates by Country 2021. Walnut: World Population Review. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Xu, Qianshu, Qiao Zhengxue, Kan Yuecui, Wan Bowen, Qiu Xiaohui, and Yang Yanjie. 2025. Global, regional, and national burden of depression, 1990–2021: A decomposition and age-period-cohort analysis with projection to 2040. Journal of Affective Disorders 391: 120018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Stephen, Saylor O. Miller, Wen Xu, Allen Yin, Bryan C. Chen, Ander Delios, Rebecca Kechen Dong, Richard Z. Chen, Roger S. McIntyre, Xue Wan, and et al. 2022. Meta-analytic evidence of depression and anxiety in Eastern Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 13: 2000132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferlander, S.; Mäkinen, I.H. The Value of Quality in Social Relationships: Effects of Different Dimensions of Social Capital on Self-Reported Depression. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100568

Ferlander S, Mäkinen IH. The Value of Quality in Social Relationships: Effects of Different Dimensions of Social Capital on Self-Reported Depression. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):568. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100568

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerlander, Sara, and Ilkka Henrik Mäkinen. 2025. "The Value of Quality in Social Relationships: Effects of Different Dimensions of Social Capital on Self-Reported Depression" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100568

APA StyleFerlander, S., & Mäkinen, I. H. (2025). The Value of Quality in Social Relationships: Effects of Different Dimensions of Social Capital on Self-Reported Depression. Social Sciences, 14(10), 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100568